This film was a huge stepping-stone for me. I’d just been offered The Eagle Has Landed so was in the unenviable position of having to decide between the two. Luckily I chose A Bridge Too Far, not realising at the time what a mammoth production it would turn out to be. It was one of the biggest films of its time, costing a massive $25 million. Robert Redford got $1.2 million for just ten days’ work! And it had every star you could think of: Sean Connery, Anthony Hopkins, Laurence Olivier, Gene Hackman, Dirk Bogarde, Ryan O’Neal and Michael Caine for starters. In harrowing detail it told of the Allies’ calamitous military campaign at Arnhem in Nazi-occupied Holland, code-named Operation Market Garden; Montgomery’s bold gamble to end the war in a single co-ordinated thrust.

Alf Joint got me the job. Alf’s a very knowledgeable stuntman, a great ideas man. In his prime he was a fabulous double for Richard Burton; he did all the stuff on Where Eagles Dare, including the fight on the cable car. In fact they nicknamed the film ‘Where Doubles Dare’. And he doubled Lee Remick on The Omen, doing the high fall out of the hospital window crashing into the ambulance. He was an amazing stuntman. Alf was up for stunt co-ordinator on Bridge and went to see Richard Attenborough, the director, who was desperately worried about the age of the stuntmen because all the soldiers who fought at Arnhem were 19 or 20 years old, young kids basically. Back in the mid-70s there were very few young British stuntmen around and Dickie was going, ‘I need young stuntmen, we can’t make these old men look like these young kids.’ So Alf said, ‘I work with young people all the time, like Vic Armstrong.’ With that Attenborough almost did a back-flip. ‘I love Vic, that’s exactly the type of person I want.’ Of course he remembered me from Young Winston. So Alf called my house in a panic. ‘You’ve gotta do this film or I’m in big trouble. The only reason I got the job is because of you.’

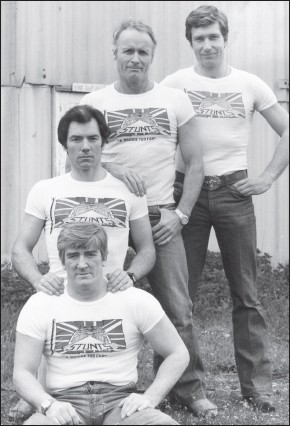

On the banks of the Rhine for A Bridge Too Far. L-R Alf Joint, Dougie Robinson, me, Paul Weston and Dickey Beer.

I had the tremendous pleasure of working with Vic Armstrong on two pictures I directed, Young Winston and A Bridge Too Far. I also had the enormous pleasure in presenting him with the Michael Balcon Award for Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema at the 2002 BAFTA ceremony. It was an award he richly deserved because in my mind Vic Armstrong is one of the outstanding organisers and performers in the film industry.

So I ended up as stunt co-ordinator with Alf and went off to Holland. Later my wife Jane and young son Bruce came over and we rented a lovely little house in Deventer and stayed for six months. It was a gloriously hot summer and Bruce learnt to walk. It was just an amazing film, with massive action set pieces like the taking of Nijmegen Bridge by American marines after crossing the Rhine River. That was recreated ‘for real’ and it was very dangerous because we used the same canvas boats as the original attack, and the current was extremely strong. But we had a lot more chance than the poor guys that actually did it in the war, with no outboard motors. Redford was involved in that and refused a double. All the stars were keen to get stuck into the action.

It was lovely meeting some of the brave old soldiers that fought at Arnhem. Most of the scenes in the film were based on actual events, so if those people were still alive they came out to watch it being shot. Perhaps the most moving were these two guys in a 50-calibre machine gun nest that got a direct hit. One had his hands blown off and the other was blinded. The guy with the missing hands picked his mate up with his bloody stumps, threw him over his shoulder and started running for safety. The blind guy was screaming his head off. ‘For Christ’s sake shut up,’ his mate said. ‘But you don’t understand,’ the blinded soldier protested, ‘I’m badly hurt.’ It wasn’t until later that he discovered his mate’s hands had been blown off. Amazing people; I remember them sitting behind the camera with tears running down their faces as this scene was being re-enacted.

Another day my stunt team went for lunch in a café and I noticed a little old man staring at us with mounting fury. I then realised we were all dressed as SS officers and it was obviously invoking terrible memories. If he’d had a gun he’d have shot us all. I mentioned this to the guys and we got up and went back to work. But it did bring home to everyone the realism we were dealing with, and what the Dutch went through.

Another of the really big sequences was the parachute jump that involved 2,500 people in the air. I was doubling Ryan O’Neal, to get a close-up shot of his character landing. My parachute was attached by little hooks onto a huge ring that a crane then lifted up 80 feet in the air – that’s a long way when you’re just hanging there. I’d then be released, the parachute would fill with air and I’d land safely. That was the idea.

The day of the mass drop was really windy and as I was yanked up on this bloody thing the parachute started flapping about wildly. Suddenly ping, ping, ping, three of these little hooks came loose, then a few minutes later, ping, ping, ping, more came out. Jesus Christ, I thought, any minute the whole thing is going to go. I must have been up there a quarter of an hour waiting for those bloody planes to fly over and everybody else to bail out, while all the time more bloody hooks were popping off, and more slack was building up in my parachute. When it came to the moment they pressed the button and I just went into free fall, but because so many hooks had ripped off I’d only got half the parachute full of air, and it sheered off sideways and backwards. From 80 feet up I must have gone 200 feet sideways. I didn’t land in front of the cameras as planned but backwards on a road, whacking my head on the ground. Luckily I was wearing an army helmet, but I still saw stars. I got up, happy to be alive. We never bothered setting the shot up again; it was a one-off that didn’t work. But it was a stupid thing to do and needless to say that rig was dumped. Only later did I find out that it was illegal in America because it was too dangerous, people got killed using it.

Going up 80 feet on the stunt rig that almost cost me my life.

One of my jobs on the film was to hire stuntmen, aware that Attenborough didn’t want any of the old timers. It was quite a problem. So I phoned my brother Andy, who at the time was an assistant director on The New Avengers TV series, and asked if he’d come across any young stunt guys. ‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘There’s this guy from Yorkshire, Roy Alon, he’s a complete mad man. We asked him to fall out of this car, and at 25 mph he just pitched himself out on his head, bounced and rolled down the road, got up and said, “Was that all right, chuck? Do you want to go again?”’ ‘Stick him on the list,’ I said. Roy and I worked together on countless movies after that and he became one of the UK’s most prolific and successful stuntmen and co-ordinators. It’s amazing how many of those young stunt guys that came out to work on Bridge, many just starting off, are now stunt co-ordinators in their own right.

I must have used about 100 different stuntmen during that production, but poor old Roy Alon was always the butt of the jokes. In those days we never had specialist stunt padding so made do with judo pads. Sometimes we’d put a wetsuit on underneath the costume for added protection; unfortunately they were bloody hot. 1976 was the warmest summer we’d had for donkey’s years and we told Roy to get ready at ten o’clock in the morning for a fall out of a car we were shooting that afternoon. Come midday he was cooking inside this wetsuit and army uniform. Of course we all buggered off for lunch and left him lying on the edge of the bridge. When we came back there were pools of water where his arms were hanging down; sweat was running out of his sleeves. ‘Are you all right Roy?’ we asked. ‘Aye, I grant you I’m hot, but I’m all right.’ We never did do the stunt; we were just winding him up.

The film was a logistical nightmare too, just getting people in and out of the location. We also had a huge crew of engineers who kept all the tanks and trucks running. That was funny because just before I went out to Holland I bought a Volkswagen estate car from a guy in a pub for £100, and took it in for a free service from these film engineers. The next day I got this panic call. ‘Vic, don’t go more than 20 miles away from base in that old thing, it’ll break down.’ I ignored them and did the whole six months on Bridge driving all over the bloody place. After that I took the family back to England, returned to Holland for a month’s extra filming, drove to Vienna to work on another picture and then drove back home again. I kept that Volkswagen for another year until my wife was backing out of the garage one day and the suspension went, so that was the end, two years after being told not to go more than 20 miles in it; never had a lot of faith in engineers after that.

I learnt an awful lot working with Alf, especially the importance of rehearsals. For the scene where the Germans attack the British position on the bridge in assault vehicles we used a big car park and mapped out the whole sequence, what each vehicle was going to do, how it was going to be shot and how each stuntman could be utilised in four or five different parts. All the big set pieces were meticulously planned and the stunt team was coming up with all these great ideas for action sequences. Paul Weston did some really inventive storyboards of a German patrol coming down an alpine pass and being ambushed by the Dutch resistance, until we said to him, ‘It’s great Paul, but Holland’s as flat as a pancake, there’s no Alps here.’ ‘Oh bugger,’ he said.

One day in this car park I slipped arse over tit. Looking down I saw these ball bearings, no bigger than grains of sand. They were actually unexpanded polystyrene, but hard as granite and completely round so if you put them on the ground it was just like ice. So I had this idea we’d use them for car spins, because a German Kübelwagen had to come down the bridge and slide sideways. We did a rehearsal and threw handfuls of this stuff on the ground. Marc Boyle was driving and Paul Weston was hanging on the side. The Kübelwagen roared towards us and did an amazing spin, but unfortunately when the ball bearings ran out it gripped hard on the real road surface, jerked sideways and then flipped upside down with these two guys in it, no roll cage or anything. Oh my God they’re dead, I thought. Marc stayed inside and Paul got thrown out; unbelievable how it never killed them. We never used the stuff again after that.

Alf Joint bit the bullet on that film too. He was a great high fall man and played a German sniper that got shot and fell off a building. Attenborough yelled action and Alf pitched off the edge of the roof and straight down the wall. Unfortunately he wasn’t totally used to the modern technology of airbags which is based on displacement, you land in the middle of the airbag and the air gets displaced through vents, but he landed on the edge so it was like a tube of toothpaste, it squeezed the air all up one end and he had no resistance. He collapsed his lung, chipped his shoulder blade, broke a rib and chipped his hip. But true to his profession he was back with us as soon as he got out of hospital.

As well as being a great learning curve for me, being in charge on A Bridge Too Far with Alf lifted me up in the hierarchy of the stunt business. I was now employing all the people that in the past had employed me, and I was also employing possible future employers. I also started my own company, Stunts Incorporated, on that movie, mainly because we were getting fed up of American stunt teams coming over here with hats and T-shirts with their logos on them. The Brits aren’t really into that, we’re all very retiring and too embarrassed to say how good we are, so I thought, let’s give it some panache. After all, the film business is all about salesmanship.

The original members of Stunts Incorporated: myself, Alf Joint, Paul Weston and Dougie Robinson.

It all started as a T-shirt funnily enough. John Richardson got one made for his special effects crew and when we asked for a few they said, ‘No, only special effects people can have these T-shirts.’ They all proudly walked on the set wearing them one day and the producer Joe Levine happened to be there and went, ‘Jesus Christ, am I paying this many special effects guys?’ He suddenly realised there was a 40-strong effects crew, who were basically anonymous until that moment. They never wore those T-shirts again! So we thought, right, we’ll get a T-shirt going, but for anyone to have. The design was the British flag with the bridge coming out of it, later replaced by a simple movie camera logo, and they were so sought after because everybody loves stunts – I’ve even had them stolen off my washing line at night.

We managed to get some great publicity out of it. We gave one to Joe Knatchbull, our location manager, who was Lord Mountbatten’s nephew and was at the time going out with the same girl as Prince Charles. Joe went home one weekend and a few weeks later in all the papers was a photograph of Prince Charles wearing our T-shirt playing polo, he put it on in between chukkas to cool down. And everybody went, wow, the stunt Prince. But old Joe Knatchbull was pissed off because he’d given the T-shirt to his girlfriend and she’d given it to Prince Charles, and that’s when it came out that she was double dipping a little bit. But it got huge coverage all over the world. We must have made a million T-shirts since then because we used them on every film we did.

So that was the start of Stunts Incorporated. The original formation was Alf Joint, Paul Weston, Dougie Robinson and yours truly. It was a philosophy of sorts, a group of individuals who were the best at what they did. And we employed the best people because you’re only as good as the people that work for you. People don’t hire Stunts Incorporated as a company to carry out jobs, what they’re doing is employing somebody who just happens to be a member. It’s merely a badge to sell the person without them having to promote themselves. They see you walk onto the set with Stunts Inc on your chest and they know you’re a capable stuntman. It’s all about the individuals and not the group itself. I’ve always striven to keep it that way, and it seems to work.