TWENTY-SEVEN

The instrument he held was small, simple, shaped like a fan, or a quiver, or a horn. A rounded wooden butt blossomed into a backboard, long and slim, a single piece of alder wood widening to a scroll and a slant. Shined with beeswax, oiled with flaxseed. It was of a size to be laid across her knees, and had five horsehair strings that fanned out with the wood, raised above the surface, pegged with amber. The strings were stretched across a slim bar of gold.

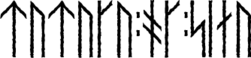

‘I told you my grandmother was a Lapp,’ he said. ‘From Finland. She had one of these; they call these instruments “kanteles”. And they say there’s magic in them, that they heal a heart. That they’re best made when one you love has died, for part of them lives on between its strings.’

He paused, uncertain. ‘I didn’t really know how your harp looked. This was the best that I could do instead …’

She was looking at him very strangely. He knew what he was meant to say – that he was sorry for her loss, that he understood how badly she felt, that it would get better, in time – and couldn’t say a word of it. So he held out the honeyed, smooth-grained harp, and hoped that she would take it.

Inside Astrid, something was unfurling. From stony, frozen depths it stirred, creeping upwards, touching her with its teeth and claws. Where it touched, she felt again: felt grief, and loss, and pain. At last. This, she supposed, was love. It hurt. And that was good.

So she reached up, and took the harp. Laid it in her lap, stroking it as if it were a cat, not yet daring to pluck a string.

‘It has no tuning key,’ she said, surprised. They were the first words she’d spoken in several days.

‘It shouldn’t need one. All the strings serve you.’

He pointed to the middle of the five strings. ‘That one especially will change at will: if you’re happy, the string will tighten up. And if you’re sad, it slackens, like a back.’

There were so many questions to ask, she thought. But then, he looked so very, very tired.

‘Play, Astrid,’ he said. ‘Just play.’

So she did. She learnt her way round the five strings, teasing out chords. The first, the fourth, the fifth string – and all heads in the hall turned at the sound of that expectant, hopeful clutch of notes.

First, third and fifth, and listeners stiffened as the major chord followed, the two together sounding like a calm but murky sea, something shifting under the waters.

She plucked the same three strings, but now the third slackened of its own accord, the minor note wrenching the whole sound into strife. She followed, fingers nimbling, with first, second, fifth, then first, first again and fifth, and the sequence spoke of earth and grave and the certainty of darkness.

Those five chords, over and over again. Shovel after shovel of dank soil, heaped upon hope, heaped upon joy.

No one was speaking. The jarls had all sunk down upon the benches, heads cast low. Tofi of Baekke was already weeping loudly as the music filled the hall. It was less the sound of sadness than despair.

Something struck Leif. If Astrid could conjure such sadness from these strings that it broke men’s hearts, then maybe it could turn their heads. Maybe this would be the way to beat Folkmar.

And in that case, he wouldn’t have thrown everything away by his choice to make the harp. He would have helped Astrid, and saved the north lands. He could have both, couldn’t he?

Couldn’t he?

Astrid’s sequence suddenly jarred, both third and fifth strings going slack, and the eerie, diminished chord stirred the slumped listeners so they shifted in their seats. And now she began a new tune, lighter, with more movement, and this one was the sound of tears itself.

Everyone was crying now. And Leif really dared to hope, that his choice had been the right one, not just for Astrid, but for the land as well.

Even Folkmar was crying. ‘Beautiful,’ he said, wiping tears from his fat eyes. ‘Beautiful!’ He waddled across to Astrid, laying one heavy hand on her shoulder. With the other, he pawed at her hair, lovingly. She shuddered, trapped by the weight of him.

And then he turned to the silent jarls. ‘It is a miracle,’ he said. ‘A miracle. That the girl should play like this, on today of all days.’

‘What day, bishop?’ said Haralt, coming back to his normal self.

‘Why, it is November the twenty-second, Saint Cecilia’s day. She who watches over all the musicians; she who died with a song on her lips praising Our Lord, and is now by His side in Heaven! It is Saint Cecilia who is making this music so beautiful!’ And his piggy eyes shone with emotion.

All around, jarls were nodding.

Oh skita, thought Leif.