CHAPTER THREE

So in Debt

The anthropology of debt

I don’t do favors. I accumulate debts.

—Sicilian proverb1

The gift is to the giver, and comes back most to him—it cannot fail.

—Walt Whitman2

Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.

—Charles Dickens3

When I lived in London, there was this guy I knew. Tall, handsome with a faint hint of a unibrow. He joined my buddies and me for drinks after work. One by one, we took turns signaling the bartender and logging an order of four pints of Guinness. After downing a few and feeling slightly wobblier, we were ready for one last round. Everyone gazed in the direction of the only person not to have paid for a round, this guy.

A friend asked him, “Can we get another round?”

“Sure, but I’m not paying for it.”

Awkward silence.

After determining that this guy wasn’t kidding, the same friend concluded, “That’s weak, mate. I’ll get the last round.” And on went the conversation. But this guy had turned into that guy—the one who doesn’t cover a round of drinks for friends.

That guy, I must admit, was me.

I ran this crude social experiment in the friendly confines of a local pub to see what happens when there’s a gross violation of an implicit agreement to pay. Of course I ended up paying for a round of drinks, joking away my previous remark. But for a few moments, I moved from being a stand-up guy in the eyes of my pals, taking part in a social ritual, to being a freeloader, abusing the generosity of others.

There is no law written anywhere that says you must buy the next round of beers. But most of us know what’s expected. My friends and I were engaging in an exchange as primitive as it is modern: accepting a gift and reciprocating the favor; incurring a short-term debt and repaying it later. The use of money, in this case, was governed by the social mores of our little tribe.

Money is interpreted differently across the world, in various parts of the “super-brain.” The ways in which people use money reveal how they conceive of it. Anthropologists have trekked to distant corners to study the uses of money, discovering unusual practices and documenting how money plays an important role from birth to death. In India, money is given to newborn babies and their parents. In Japan, money is gifted to newly married couples.4 In Nigeria, many corpses are buried with money.5 Money marks many important moments of our lives and in countless ways.

Despite the numerous ways in which money is used today, it functions universally as an instrument to settle debts. Printed on the dollar bill is written as much: “This note is legal tender for all debts, private and public.” Dollars are issued by the Federal Reserve, and they show up as a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet. The collateral that backs the bills is found on the asset side of the balance sheet. These assets are mostly securities issued by the US Treasury and federal agencies.6 In other words, dollars are obligations of the US government, and they are backed by the debt of government institutions and the faith of the government. In the current US monetary system, money and debt cannot be disentangled.

Those little words printed in black ink are also a reminder of money’s alternative past. For centuries, economists have contended that bartering was the precursor to money. But there was actually another financial instrument in wide circulation: debt. Thousands of years before the invention of coinage, there were interest-bearing loans in ancient Mesopotamia. Debt was the forerunner of money. Today we may see money and debt as two different things, but they share a common origin. That the dollar is a liability, an obligation of the Federal Reserve, reveals how fundamental lending and borrowing have been throughout man’s history.

That’s because debt isn’t just a financial obligation, it’s a social one. In this chapter I use an anthropological approach to examine both types of obligations. I examine different spheres of debt exchange: (1) the familial sphere, the basis of the gift economy; and (2) the commercial sphere, or the foundation of the market economy.7 I focus more on the gift economy because it’s more nuanced and open to interpretation. But it ends up shaping our perceptions of money, and even influences how we view our friends and family.

It’s evident that auto loans and mortgages are financial debt instruments with listed prices found in the market economy. It’s less clear how to quantify a social debt or credit brought on by receiving or giving a gift. The practice of gift exchange, enacting a social debt, can be found in most cultures, from the intricate gifting culture of East Asian countries to gifting a friend a beer in East London.

Regardless of which sphere one finds it in, debt brings with it a sense of obligation. For as long as we’ve been around, we have taken on debts, both social and financial, and have been obliged to honor them. And obligations have moral overtones. Not to reciprocate a gift like a beer can be interpreted as breaking an implicit, unspoken social understanding. Not to repay a loan breaks a contractual agreement. Not to honor thy debts is wrong. To reciprocate and repay is to make good. Then again, it’s also wrong to take advantage of people through usury and predatory loans. I save the religious strictures on debt for another chapter, and instead focus on what happens when a social debt is computed as a market one. This can result in the dark side of debt, using money as a bludgeon to control others.

An Alternative Origin

In most introductory economics classes, the history of money goes something like this: Once upon a time, in a land far away, people bartered goods, but sometimes each party didn’t have exactly what the other wanted, so they invented money. You can trace this line of thinking to Aristotle and classical economists like Adam Smith, who contended that a division of labor led to more specialized tools, which necessitated money to facilitate increasingly complex trades. Adam Smith writes in The Wealth of Nations:

The butcher has more meat in his shop than he himself can consume, and the brewer and the baker would each of them be willing to purchase a part of it. But they have nothing to offer in exchange, except the different productions of their respective trades… In order to avoid the inconveniency of such situations, every prudent man in every period of society, after the first establishment of the division of labour, must naturally have… a certain quantity of some one commodity or other, such as he imagined few people would be likely to refuse in exchange for the produce of their industry.8

Smith goes on to say that through exchange, commodities such as nails in the Scottish Highlands became early currencies. And over time, these commodities were replaced with small pieces of precious metals. My evolutionary biological investigation into the origin of money even supports this notion that bartering commodities, perhaps food items and hand axes, paved the way to using money. A romanticized, simplistic notion of tit-for-tat bartering seems to be a forerunner to monetary exchange: Here’s three silver coins, and good-bye.

However, writing in the Banking Law Journal in 1913, a British economist questioned this theory. Alfred Mitchell-Innes asserted that there is no historical proof for Smith’s axiom, and that it is, in fact, false. He notes that Smith’s example of nails was even debunked by William Playfair, an editor of The Wealth of Nations. The nail makers were poor. The makers had to rely on suppliers to furnish them with the raw materials to make the nails. The suppliers also provided credits to the makers for bread and cheese while they were making the nails. The nail makers were in debt. When the nails were completed, the nail makers paid back the suppliers with the nails.9 Mitchell-Innes writes, “Adam Smith believes that he discovered a tangible currency, [but] he has, in fact, merely found—credit.”10

His paper received a modicum of attention, though it did receive plaudits from economist John Maynard Keynes. But it was long since forgotten for almost a century. It resurfaced in the twenty-first century, when notable economists like L. Randall Wray and anthropologists such as David Graeber saw its merit. Wray asserts that money and debt may be one and the same—that money is simply a measure of debt.11 In Graeber’s book Debt: The First 5,000 Years, he draws attention to the work of several anthropologists who have studied barter. One of them is Caroline Humphrey of the University of Cambridge, who writes, “No example of barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing.”12 Graeber connects the dots, saying that this lack of proof calls into question the conventional theory of how money originated. And it suggests such a foundational theory as to how money developed is a myth.13

However, before dismissing bartering-led-to-money entirely as myth, Graeber provides a bit of nuance. Indeed, many folks have bartered as a means of exchange, swapping one good for another. But it’s usually with strangers—someone you may not ever see again, so the goods must be something of value.14 I once bartered a beer in exchange for someone buying me a ticket to a baseball game. The cashier didn’t accept credit cards, so the guy behind me paid for me with cash, and I promptly went to the first restaurant at the stadium and bought him a cold one with my credit card. To barter with someone you know may suggest a deficit of trust. Why not do a deal on credit? That requires confidence and faith, as the Latin root of credit means “to believe” or “to trust.”

Not trusting your counterparty, not doing a deal on credit, can introduce a competitive aspect to bartering, in which barterers try to seize the upper hand. Graeber mentions the Pukhtun men of Pakistan, who barter with nonrelatives. They swap items in similar categories, like a shirt for a shirt. They also swap items of different categories, like donkeys for a bicycle. Winning a trade, getting the more valuable good, is reason to crow.15 They aren’t following the first step of Tit for Tat. They’ve assumed there won’t be a second iteration of the game and are content to maximize the gain on the first move. In a credit system, the first move requires trust and cooperation.

Graeber, like Mitchell-Innes, asserts that before there was money, there was debt. Interest-bearing loans first appear in ancient Mesopotamia, thousands of years before the invention of coinage in the Kingdom of Lydia. In Mesopotamia, those who worked in temples, palaces, and prominent households calculated loans based on the prices of commodities like silver and barley. It also turns out that putting beers on a bar tab is an age-old practice, common in ancient Mesopotamia as well.16 He ultimately concludes that debt predated or at least developed simultaneously with money. Given the historical importance of debt, it’s necessary to understand its various dimensions.

Debts of a Different Type

In West Africa, it’s forbidden to exchange cloth for yams. In the Solomon Islands, it’s prohibited to trade taro for turmeric.17 These peculiar rules are examples of spheres of exchange, in which items are assigned to a category and can be traded with items of the same category but not those in another group. Several cultures draw distinctions between spheres of nourishment and those of material goods. For instance, Tiv people of Nigeria have three spheres of exchange: (1) food items like grains and vegetables; (2) more lasting, prestigious items like brass rods and horses; and (3) “dependent persons” like children. The Siane people of New Guinea also have three spheres: (1) food items like bananas and taro; (2) luxury items like tobacco and nuts; and (3) ornaments like seashells and headdresses.18 To mix spheres not only demonstrates ignorance but can also be insulting, as if you’re trying to take advantage of the person with whom you’re trading.

To transact smoothly in any society, it’s important to know what’s exchangeable for what: You don’t exchange a Bentley for a hug (but you might give someone a hug if they give you a Bentley). There are different spheres of debt exchange in contemporary societies. Consider these two exchanges:

1. Miriam invites you over for a home-cooked meal of honey barbecue meat loaf.

2. You agree to a fixed-rate mortgage to finance payment on a new house.

The first exchange is in the familial sphere, with friends and family outside the marketplace. Because of Miriam’s generosity you feel an obligation to reciprocate with a benevolent gesture of your own, like bringing a bottle of Petite Sirah wine, writing her a handwritten thank-you note on embossed stationery, or inviting her to a summer picnic in Central Park sometime in the future. The gift, the transfer of wealth or valuable goods, is only one part of the exchange. Also being exchanged may be respect, thanks, admiration, or a range of other things. This gratitude-induced obligation serves as the basis of what’s known as the gift economy, found in ancient and contemporary societies all over the world.

The second exchange, involving the home mortgage, occurs in the commercial sphere, usually with strangers. There is an obligation to make the mortgage payments in full and on time. This legally induced obligation is part of what we today call the market economy. When we compute a debt obligation with money it can take the form of financial instruments like student loans, auto loans, and credit card bills.

Both exchanges result in an obligation of varying strengths to repay. But the method of payment is different. In the familial sphere, you would repay Miriam with an in-kind gift, and the interaction might then be considered complete, though it is likely to sustain a virtuous circle of future giving and receiving. But to mix market practices within the familial sphere can make for awkward situations. Say after aperitifs, appetizers, delicacies, and dessert you ask Miriam how much you owe her. You take out a billfold, count aloud eighty-five dollars, and press the cash into the palm of her hand. If Miriam is like most of my friends, you will offend her for treating her hospitality as if it were a good that can be purchased at the local Trader Joe’s. You introduced a market practice, paying for services rendered with cash, into a social situation.

Of course, these two spheres are not mutually exclusive. They keep bumping up against each other. Companies try to blur the lines between these spheres for their benefit: Treating a client like a dear friend or family member is a characteristic practice of effective salespeople everywhere. And frequent-flier and other reward programs are designed to instill a sense of loyalty and obligation that gives you pause before you return to the marketplace. These companies are trying to enter your familial sphere so that you will view them more favorably and less like a stranger. The more you trust them, the more they can sell you. But even still, Best Buy isn’t the same thing as your brother.

The Gift

Marcel Mauss was a multidisciplinary man, chock-full of ideas. Part sociologist, part anthropologist, part philosopher, he wrote in 1924 Essai sur le don, or “The Gift,” which still serves as a foundational work for anthropologists who study gift exchange.19 A gift can have political, economic, social, even religious dimensions, and studying it requires a broad, panoramic lens. A gift can take on several meanings because it reflects the intent of the giver, which can range from benevolence and munificence to solicitation and contempt. For example, say Miriam invites you to dinner to butter you up before she requests that you help her son gain admission to a select university that you attended. Her gift, the lovely dinner, now drips with additional meaning. And if you had known her intentions before the dinner, you might have rejected the invitation.

Gift economies have their unique flavors of rituals and customs, but Mauss observed that they usually involve three types of obligations or principles: to give, to receive, and to reciprocate.20 These obligations make up the cycle of the gift economy. The constant movement of gifts, which I will trace across several cultures, suggests that the currency of gifts, and debts of the familial sphere, bear a similarity to the movement of money in the commercial sphere. However, the difference is that movement or “transactions” in the gift economy usually sustain relationships. After you receive a cappuccino from a friend, the relationship is sustained and even strengthens, and you’re obligated to reciprocate the gesture at a later date. When a gift is given, despite money never changing hands, there is still another currency in circulation: familial or social debt. In the market economy, after you buy a caramel Frappuccino from a Starbucks barista, the relationship ends and you go your separate ways.

Mauss recognized how gifts sustained the relationship among the Maori people of New Zealand and nature. The Maoris speak of gifts as having a hau, or spirit. Hunters who catch game from the forest give some meat to priests, who perform rituals on it. By doing so, the priests arrange a mauri—for example, game prepared during a ritual ceremony or sacred stones—which is a physical manifestation of the forest’s hau.21 They offer the mauri back to the forest as a demonstration of gratitude for nature’s gift. Not to demonstrate proper gratitude can upset nature and diminish its future bounty.22 In general, a gift’s hau is said to have a yearning to return to its place of origin, encouraging recipients to reciprocate the gift. The forest, hunter, and priest are all givers and recipients, playing their roles in the cyclical movement of the gift. Several scholars have attempted to debunk Mauss’s spiritual interpretation in favor of a more secular understanding: Not to reciprocate a gift would harm the reputation of the recipient.23 Even still, the movement of a gift shows the currency of the gift economy in full circulation.

We see the circulation of gifts on a larger scale in the Trobriand Islands, near New Guinea, where anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski found locals practicing a gift exchange called the Kula. Two types of ceremonial gifts, or vaygu’a, necklaces and armbands, are exchanged among families on the many islands that make up the Massim archipelago, and they function like a type of currency.24 Both gifts move in a loop around the islands: Red shell necklaces move in a clockwise manner, and armshells move in a counterclockwise fashion. The gifts are exchanged for each other: Receiving a necklace should be reciprocated by giving an armshell now or up to one year in the future. It can take up to ten years for gifts to make it all the way around the islands, as folks travel long distances via canoe to other islands.25 The cycle of gift exchange, incurring social debts and repaying them, gives shape to the society—knowing where folks stand in relation to each other, like a large credit system. To hoard a gift for too long risks your reputation or credit. Not to give means ending one’s social ties and withdrawing from the community. Giving is expected and is part of being an upstanding member of the group.26

The constant movement of gifts in the gift economy is in contrast to the buying and hoarding we often associate with Western societies. In the Trobriand Islands, and in many so-called archaic societies, Malinowski observes that “to possess is to give.”27 Translated into modern parlance: Pay it forward and keep the gift moving. In his illuminating book The Gift, author Lewis Hyde contrasts divergent cultural views regarding the movement of gifts with a thought experiment. Say an early English settler visits a Native American community, where he is given a pipe. The settler gladly accepts the pipe and displays it proudly at his home. When members of the Indian tribe visit his home, he learns that they expect him to give them the pipe. He bemoans the Indians’ disrespect for private property. To him, to receive a gift is to remove it from circulation, maybe even turning it into a commodity that can be sold later. He sees them as what has been called an “Indian giver,” someone who wants their gift back—a phrase with a stereotypical and negative connotation that may stem from Lewis and Clark’s expedition, when they encountered difficulties trading with Native Americans.28 In Hyde’s thought experiment, the Indians bemoan the settler’s disrespect for the movement of the gift and the wider community. To them, to hold a gift is to continue giving and regifting, sustaining relationships.29 Here we have the familial and commercial spheres coexisting, albeit uneasily.

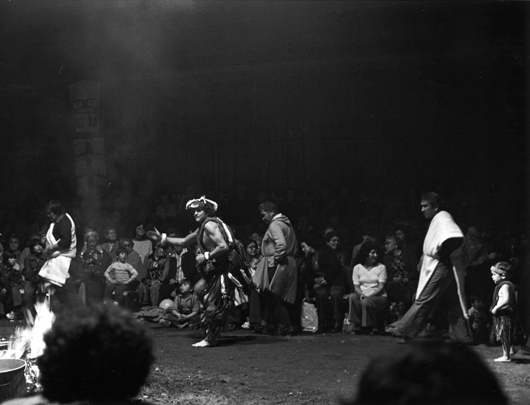

To give, in some societies, is part of a formalized way to gain status. Anthropologists in the nineteenth century, including Mauss but starting with Franz Boas, who studied the Kwakiutl people, a native tribe of British Columbia, spilled considerable ink explaining the potlatch (not to be confused with a “potluck,” which is of English origin). A potlatch is a ceremonial gift exchange that historically took place among native communities in the Pacific Northwest. Potlatches were organized for noteworthy occasions like births, weddings, and funerals. But the purpose of most potlatches was to make or demonstrate a social claim, for instance, the ascension of a new chief after the death of the previous one, like a coronation ceremony in which a new king is crowned.30 The new chief was usually the firstborn son, and it was his role to preside over the potlatch. Social mobility was limited, and potlatches reinforced hereditable claims to power through rituals.31

Most native communities of the region had their own twist on the potlatch, but there was some similarity in format. The chief and his wider kin group, or numima, as it’s known in the Kwakiutl society, invited guests to witness the important occasion. The potlatch became a public spectacle in which the chief or “donor” and numima prepared a feast and led rounds of oration, singing, and dancing. At the end, the donor distributed gifts to guests, as a symbol of generosity and a signal for the guests to leave. Gifts reflected the prestige of the donor instead of the desires of the guests. Therefore, higher-valued items like meats and skins were often given as gifts. Kwakiutl coppers were another notable gift, made from metal sheets adorned with the names of previous owners. Over many generations these coppers changed hands through a series of many potlatches. Enshrined on the coppers is a history of gift exchange during this era.32

Indeed, potlatches helped to integrate families and build solidarity among the wider community. But they also served as a way to distinguish among members, to identify an individual’s status and rank. Gifts were distributed in order of each guest’s rank, so the recipient knew exactly where he or she stood in the eyes of the donor, as no two guests had an identical rank. Recipients also contrasted the gifts they received among themselves, as a way to gauge their own relative status.33 For example, in one potlatch feast, a seal’s breast was served to the chief, whereas the flipper was given to the second in command. Members with lower rank received lower-quality cuts of meat.34

Giving gifts, and openly “destroying” one’s wealth, is a virtue in these Kwakiutl societies. It contrasts with the notion in Western societies of gaining status through accumulating wealth.35 In fact, from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century, potlatches were deemed illegal in Canada’s Indian Act because they supposedly stood in the way of cultural assimilation. Destroying wealth was seen as a blatant disregard for private property.36 Upon further analysis, there’s a competitive spirit to the potlatch. Although gift giving in the potlatch has the patina of generosity, many tribes became competitive about it, trying to outdo their previous potlatch and those organized by their neighbors, lavishing their rivals with outsized largesse. However, as the native communities shrank in population, due in part to diseases contracted from foreigners, claims to status and rank were blurred. Sometimes there weren’t enough members to fill all the positions of status. Disputes between members who claimed the same rank or status were settled by whoever organized the better potlatch. What had initially served as a way to limit social mobility, the potlatch had become a ladder for it.37

Over time, as these native communities traded with Western settlers, some newly procured items, like clocks and, later, sewing machines, were injected into potlatches, along with norms found in the commercial sphere. These goods gradually took on traditional meanings, and eventually a donor’s prestige was derived mostly from the monetary value of his gifts. Status now came from a market price instead of a hereditable claim. Coppers were measured on scales, and gifts were seen through the lens of money and the market economy. The potlatch had been transformed. Market norms had made inroads into the familial sphere.

Gift economies aren’t found only in societies from centuries ago. Such modern public displays of gift exchange that sustain a web of relationships can be found on the World Wide Web and online platforms. Founded in 1999, peer-to-peer music-sharing service Napster dramatically altered music consumption: Instead of buying music in the marketplace, users shared or gifted their collections of MP3 music files with one another. After downloading a song from someone else, it was added to one’s collection, and others could download it. Though one didn’t part with the song when it was shared, it amounted to a gift for the recipient. There was constant movement, like in the Kula, as songs were gifted and regifted. Instead of a circle, Napster’s gift economy had a rhizomatic or rootlike structure, with users spread around the world.38 One researcher interviewed Napster users to better understand their motivations. Users spoke of the Napster “community” to highlight that sharing and gifting built a sense of solidarity.39 Others decried the practice of downloading music but not sharing one’s own collection of music. One user said, “If they’re not into sharing, they should not be allowed to reap the benefits.”40 Napster users developed norms and obligations similar to the societies studied by Mauss and Malinowski. Certainly, many believed Napster users were engaging in music piracy, stealing from the marketplace and sharing freely with the community. Facing lawsuits and court orders, Napster shut down. In this example, it’s the producers in the market economy that suffer from familial attitudes on sharing writ large. A valuable piece of intellectual property was shared around the world with little monetary regard for its creator.

We see the reverse, the commercial sphere benefiting from the familial sphere, with the online crowd-funding platform Kickstarter, which enables people to give money to artistic projects. Artists create short videos that explain their vision. Many have achieved incredible fund-raising success: One musician seeking $100,000 raised $1 million; a video game designer looking for $400,000 raised north of $3 million. More than $800 million has been raised on the platform.41 Kickstarter takes a fee for every successful fund-raising campaign, acting as a market agent that benefits from the money flowing through the gift economy. Those startled by the rise of Kickstarter need only remember the pervasiveness, draw, and obligations of the gift economy.42 When your artist friend asks you for money, you may feel obligated to help. There’s no large economic benefit to the giver, but the gift sustains the relationship with the artist, who provides the artistic gift along with a steady stream of updates to benefactors, and small gifts like free albums or the dedication of a song.

In all these examples, the movement of gifts relies on gratitude, or what sociologist Georg Simmel termed “the moral memory of mankind.”43 After receiving a gift, there’s a resulting gratitude-induced obligation that the recipient remembers. Though gratitude carries a warm and generous connotation, make no mistake of its strong force, a “gratitude imperative” to reciprocate a gift.44 A gratitude-induced obligation creates a tie of morality between the giver and the recipient—symbolically represented by the bow and ribbons found on presents.45 Admittedly, gratitude-induced obligations work only up to a point. When a group gets too large, it’s nearly impossible to remember how every exchange affected each relationship, and where everyone stands in the mutual web of indebtedness. Gratitude necessitates remembrance and is necessary to restoring the debt balance between the giver and the recipient.

There’s even a rough way to track and calculate one’s social debt balance. Remember from earlier that you and Miriam are counterparties in a familial or social debt exchange: Her kind gesture credits her balance and debits yours, like a social bank account or credit system. In conversation, we even use language as if we’re keeping track of balances in such a system. We use metaphors involving debt to describe our relationships with others: I owe you one; I am in your debt; I’ll make him pay.46 We may even think in terms of such a credit system. Leading linguists contend that metaphors aren’t just artful ways of expressing ourselves; they also shape how we think.47 Many folks keep an active mental account as to whom they owe and who owes them. Some even write it down: J. P. Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon reportedly keeps a list of “people who owe me stuff” in his suit pocket.48 He realizes that gifts or social credits minimize the friction of dealing with individuals solely through the market economy: The cost of doing a deal is less expensive if someone already owes you. That a Wall Street titan recognizes and keeps track of favors or “chits” shows how important the gift economy can be in greasing the wheels of the market economy.

When President George W. Bush was reelected in 2004, he said matter-of-factly, “I earned capital in this campaign, political capital, and now I intend to spend it.”49 He wasn’t just using an expressive metaphor but providing a window to his thoughts and second-term policy agenda. “Political” or “social” capital invokes the same debt metaphor. Though termed “capital,” it isn’t owned like a piece of property.50 You can’t cash it in with everyone or convert it easily into another currency like money. Its value is embedded in the relationship with whoever is on the other side of the obligation. If that person walks away from the obligation, the credits that you accrued may be worthless. It takes at least two to tango in these social debt arrangements. And because you can’t exactly “own” this type of social debt, at least in these examples, this metaphorical capital returns us to the notion that to possess is to give: The value of social capital is realized by having someone else fulfill their obligation, to repay the gift and to keep the cycle going.

Constantly keeping track of one’s social debt balance can be a source of anxiety. First, it can be difficult to reciprocate and find the right “payment” or gift. One study found more than a dozen sources of anxiety resulting from gift giving; they range from unfamiliarity, not knowing the recipient well or their preferences, to selectivity, when the recipient is highly selective in their tastes.51 For example, finding an appropriate gift for a new boyfriend or girlfriend can be difficult indeed. Too inexpensive a gift sends a signal that you didn’t sacrifice or spend enough on them. Too expensive a gift and you risk scaring them away because the money you’ve spent could signal too much commitment or seriousness at an early stage. Second, one may not want to incur a social debt obligation, as it may shift the power to the benefactor. And one may reject the gift outright. In a study on the role of gift exchange in courtship, some women resisted a man’s attempt to buy them dinner, preferring instead to “go dutch” and split the bill. To some, the gifts aren’t just a way to ingratiate but an effort to control the relationship.

Anxiety from gift exchange can push folks to escape to the market economy, which can offer anonymity and fewer lingering obligations. In Montreal, for example, some have turned to professional moving services instead of relying on friends to help them move. Historically, Montreal’s large working-class population was forced to move residences frequently. Most rental leases were for one year and started in the summer, and many found themselves moving at the same time. These days, moving in Montreal has become something of a hobby and part of the culture. Labatt Breweries of Canada has run advertisements with moving residences as the theme. A famous song by Robert Charlebois sounds a cultural note with his tune “Deménagér ou rester là,” which means “Move out or stay put.”52 Since moving houses is labor-intensive, the mover will turn to the gift economy and ask his or her friends and family to help during the move. One mover praised the cooperative nature of the gift economy: “These people who helped us, I’ve helped them move in the past… Wow! People are here for you. You’re not in a mess. You’re not alone.”53 But exchanges in the gift economy don’t always flow smoothly. If friends and family don’t show up, one may lose faith in them and feel slighted by their reluctance to help. Others don’t want the resulting obligations associated with friends and family members who have helped during the move. Mira, a forty-nine-year-old architect, says: “It would be complicated to entrust [my cousin] with the painting job because he won’t charge me the market price… I don’t want to feel obliged. I don’t want to feel that I will have to give back.”54 Escaping the gift economy for the market economy shows the lengths some folks will go to to avoid social indebtedness.

Remember Your On

In all my travels and research, the most fascinating and curious gift economy that I encountered was in Japan. Not only do we find the constant movement of gifts and the seesaw between gratitude and anxiety, but there’s a high degree of thoughtfulness and detail that goes into procuring and giving gifts. Unpacking Japanese gift exchange reveals complex ideas about social debt and gratitude.

In the mid-twentieth century, anthropologist Ruth Benedict detailed Japanese conceptions of debt, known as on and giri. On is defined most broadly as an obligation. It’s the social burden that one carries from others, such as managers or parents. A worker who receives a benefit from his manager, say a promotion or bonus, is said to carry an on to his manager. To remember your on is to feel gratitude toward whoever provided you with the benefit, and eventually to reciprocate.

The burden of on makes many reluctant to get entangled with others, as in refusing to accept casual acts of kindness from a stranger who offers a beer or a cigarette. Even today, some conceal their trips abroad from friends to avoid having to bring gifts.55 Benedict says that the Japanese have various ways of expressing thanks, such as arigato, which means “Oh, this difficult thing.”56 Another word for thanks, sumimasen, has an apologetic connotation and is loosely translated as “I’m very sorry” or “This doesn’t end.” The feeling of obligation is so deep, it seemingly cannot be repaid.57

To repay an on can be long and complicated. A man is said not to know how to repay the on to his own parents until he himself has children. To care for your children is to repay parental on that you accrued when you were a needy child. During World War II, many Japanese recognized their imperial on toward the emperor of Japan. Every gift distributed to the soldiers, from sake to cigarettes, was an advance of the imperial on. To die in a kamikaze mission was to repay an imperial on.58

Benedict describes two types of repayment: gimu is a repayment of an on that can never be totally repaid, debts you take on at birth, like on toward parents; giri is a repayment of on with some measure of equivalence.59 She distinguishes between giri to the world, repaying one’s contemporaries and extended family, and giri to one’s name, maintaining your honor, reputation, and good name. Giri is even embedded in the names of certain familial relations: Instead of “father-in-law,” it’s “father-in-giri.”60 Not to give a giri risks one’s reputation or “credit” of not knowing how to act and honor on. Giri payments are even dressed up as Valentine’s Day presents or giri choco, which means “obligation chocolate,” when women give sweets to men with whom they’re not romantically involved. One survey showed that 84 percent of women give gifts to people who have aided them, repaying an on, yet only 28 percent give to someone with whom they’re romantically involved.61 On March 14, a month after Valentine’s Day, the tables are turned and the men reciprocate with white chocolate gifts for women.

Repayment is expected even when you experience personal tragedy. My American friend’s mother died while he was living in Japan. When he returned to work, there was a pile of envelopes, known as okouden bukuro, with cash gifts that his colleagues had given as condolences. He learned that the proper protocol is to spend half of this money on return gifts such as handkerchiefs for his colleagues, known as hangaishi, or “half return.”

Anthropologist Katherine Rupp picks up from Benedict, exploring the art form of gift exchange in Japan. Not all Japanese people take part in ritualized gift exchange, but she identifies noteworthy patterns. The Japanese gift economy spells real business: The summer (chûgen) and winter (seibo) gift seasons account for 60 percent of earnings for many department stores. Stores start their seibo advertising campaigns early and hire staff to keep up with demand, just like the Christmas season in the United States. Folks are flush with cash because they receive bonuses worth two or more months of salary.62

These giving seasons began in China, possibly as a Buddhist tradition, and were an opportunity to show gratitude to one’s deceased ancestors. During the Meiji Restoration in Japan, in the nineteenth century, the government urged citizens to replace Buddhist shrines with more nationalist Shintō ones, in order to create a sense of commonality. Over time, gift giving became less of a way to honor deities. It became a way to bestow favor on one’s parents and ancestors, or simply to repay an on. Younger people today have even updated, contemporized, and merged seibo with Christmas, since both happen around the same time of the year.63

In Japan, gratitude isn’t just symbolically represented by the bow and ribbons tied around a gift, but by how the gift is wrapped—an indication of the high attention to detail found in this gift economy. Gifts for weddings and funerals are tied with a unique knot known as musubikiri, meaning “to tie completely,” and which cannot be unraveled easily.64 Gifts for birthdays, graduations, and newborns ought to be tied with cho-musubi, or a “butterfly knot,” which can be unraveled readily, suggesting that these events happen more frequently.65 To tie a funeral gift with a butterfly knot is foreboding, meaning that another death may occur. Similarly, a wedding gift tied with a butterfly knot doesn’t bode well for the success of the marriage.

Gifts with wrapping paper from top department stores indicate that the giver has spent considerable time and money on the selection. Top department stores are adamant about wrapping gifts themselves in order to control quality and maintain their reputation. On the wrapping paper is usually the store brand and address, so that the recipient knows from which branch location it was purchased. And new hires are trained over many days on how to wrap presents properly.66 The person who receives the gift is expected to unwrap it deliberately and thoughtfully. Other cultural practices include giving money in odd numbers; even numbers are considered unlucky because they are divisible. And envelopes containing money for weddings should have in the top right corner a small depiction of an abalone, which is a symbol of auspiciousness. All of this to say, it can be a highly elaborate process to give a gift and enact a social debt in Japan. Even though there’s not a formal accounting system, the Japanese gift economy acts as if there is one in place—gifts are evaluated closely. The only thing missing is a price.

Into the Wilds of the Market

Computing obligations with money can transform them into debt instruments found in the market economy, from a mortgage to buy your house to a bank loan to renovate it. Financial debt has been with us since the beginnings of civilization. Interest-bearing loans predated the invention of coins by thousands of years.

Around 5000 BC, in what’s now known as the Middle East, various types of debt instruments emerged. Friendly loans with no interest were common, but these resembled gifts: Despite not having a price, there was still an obligation to repay. Interest-bearing loans started with agriculture and farming: seeds, nuts, olives, grains, and cows borrowed by destitute farmers who repaid the loan with interest—in the form of the surplus from their harvest.67 Loaning agricultural goods, however, was fraught with difficulty. The gains on an agricultural loan were uncertain due to unpredictable weather.68

As civilization took root, the need for lending grew. Short-term interest-free loans remained since they helped people, particularly family members, cope with a crisis. But again, these loans were more like gifts. To recognize the importance of interest-bearing loans to ancient societies, consider the Third Dynasty of Ur.

Around 2100 BC, after the decline of the Akkadian Kingdom, a dynasty emerged in the city of Ur, in what is now southern Iraq, which lasted for 104 years. It’s a period known as the “Sumerian Renaissance.”69 City leaders incorporated advanced architecture, like brick buildings with sloped arches, and built walkways so that people could amble to work. Surviving documents from this period also show a society rich with literature, language, religion, and commerce.

Many documents mention a merchant known as Turam-ili. Fifty-nine tablets constitute the Turam-ili archive, now housed at Yale University. Nearly 20 percent of these records are loan documents. Turam-ili was known as “ugula dam-gàr,” which translates to “overseer of the merchants.”70 Turam-ili acted as an agent for others, buying and selling goods, and extending credit to those in need. He and other merchants made loans to finance payments and the transfer of items, a necessary function to keep any economy humming. Moneylending among merchants and others was attractive because income generated from interest-bearing loans could be used to procure even more land, animals, and slaves.71 Money made money.

During this time period, loans that required interest payments were structured in various ways. Some stipulated that borrowers make interest payments in the form of labor: Silver-based loans usually required a debtor to provide a skilled laborer; barley-based loans required the labor of an agricultural worker. Historian Steven Garfinkle says that loans that required nonlabor interest payments can be classified as “productive” and “consumptive.” Productive loans were made in silver by merchants or institutions and for the enhancement of a debtor’s living situation, such as improving their home. Consumptive loans were made in barley and intended to help a debtor make ends meet before the harvest.72 These loans also helped to reinforce the status of people in a hierarchical society, as creditors could increase the dependency of laborers.

Garfinkle calls credit a “functional necessity,” since almost everyone relied on it, destitute farmers and wealthy individuals alike.73 Affluent folks may have been trying to finance their high cost of living, or reloaning to others at higher rates. Creditors included wealthy families, merchants like Turam-ili, and large institutions.

The temples, the palace, and the households of governors and officials were the principal institutions of Sumerian society, and they were the major creditors, in some cases functioning like banks.74 They took in taxes and dues in the form of grains, animals, and silver. They also accrued income from land that had been given by kings or won during a war. They even distinguished between items that could be exchanged and those that couldn’t, publishing exchange rates and establishing the basis for trade. Acting as institutional lenders, they made interest-bearing “consumptive” loans to individuals so they could make ends meet until the harvest season—and Shamash the God of Justice was often listed as the creditor.75 Also listed were the names of the debtor, the principal amount, the name of a witness, the year the loan was originated, and the seal of the debtor. Loan contracts were agreed to orally because most people were illiterate.76 The creditor kept the sealed loan agreement until it was repaid, at which time the record was usually destroyed.

Though most creditors preferred to be repaid the principal plus interest, there were times when debtors just couldn’t make good on the loan. Declaring personal bankruptcy wasn’t an option, so there was some creative license in making repayments. When a debtor couldn’t repay a silver-based loan, they offered livestock and food. The Sumerian word for interest, máš, or “calf,” has been interpreted to mean that payments were to be made in livestock.77 There were even instances of men giving up their wives or sons to avoid interest payments.78 When debts outstanding amounted to levels at which the public threatened unrest, sometimes the royal court, usually with the ascension of a new king, decreed clean slates that canceled all agricultural debts.79

A similar practice of debt amnesty happens even in modern societies. Until recently, the first act of a new French president was to cancel all parking tickets.80

In Mesopotamia, the logic for setting interest rates varied based on the type of loan. Variation in seasonality was the reason that barley-based loans had higher interest rates than silver-based loans, approximately one-third of the principal versus one-fifth.81 These rates were inscribed in the Code of Hammurabi, named after the Babylonian king who installed it as a type of governing directive, though it wasn’t always followed to the letter, and as Garfinkle notes, may have also served as “royal propaganda.”82 Sometimes, however, temples acted like a modern central bank, dropping interest rates to lower the cost of borrowing for debtors.

Economic records suggest that interest rates declined through successive ancient civilizations: 20 percent in Mesopotamia, 10 percent in Greece, and just over 8 percent in Rome. Lower interest rates can be a sign of market efficiency and lower risks of lending, and could reflect increases in productivity and development between successive civilizations.83 However, Michael Hudson, an expert in Babylonian economics, surmises that rates were based on mathematical simplicity and not so much on economic conditions.84 In Mesopotamia, most payments, including interest payments, were measured with weights, so it was helpful to use simple fractions and round numbers. The Sumerians used a sexagesimal numeral system, a system with the number 60 as its base.85 We even use such a system today for measuring seconds and minutes. Calculating interest rates with this system was straightforward because 60 is easily divisible: The measurement of silver, mina, was split into sixty shekels, and interest was typically charged at one shekel per month on a one-mina loan. That amounted to 12/60ths of a mina per year, or a 20 percent annual interest rate. Even today, interest rate payments for some mortgages are based on a sexagesimal system, a 360-day calendar, partly because it’s easier to use. Classical Greece and Rome employed numerical systems with different bases of 10 and 12 respectively. Interest typically charged worked out to 1/10th of principal, or 10 percent in Greece, and 1/12th, or just over 8 percent, in Rome.86

In short, almost everyone needed credit, and interest-bearing loans have been integral to the functioning of economies both ancient and modern.

Sinister Bonds

Raju thought he had just landed himself a new job. A Burmese laborer, he journeyed to Thailand to work. He was required to pay a “brokerage fee,” which he couldn’t afford, so he borrowed the funds. He reasoned that his eventual income would help pay off the debt. He was then forced at gunpoint to work long hours on a Thai fishing boat. Raju said of one person who attempted to escape, “The man was tied to a post… electrocuted and tortured with cigarette butts… later shot through the head.”87 Raju courageously dove into the water, swam to safety, and lived to share his story. This isn’t an ancient tale but rather a modern one detailed in the US Department of State’s 2012 report on human trafficking.

Stories like these show that all too often, debt becomes not just a way to reinforce status but an instrument of oppression. Debtors’ inability to repay loans can result in situations that deprive them of their freedom. Debt becomes a way to control others.

In the case of a social debt, it can be difficult to determine an acceptably equivalent way to reciprocate. Without specific prices, the value of a gift is open to interpretation and approximation. With lending and borrowing in the commercial sphere, there’s no guessing because it comes with an exact price. Attaching a nominal money value to debt certainly makes clear to everyone where they stand, down to the penny. But it also provides less wiggle room when someone can’t repay. In the name of debt contracts, creditors can ask a borrower to do things that they normally wouldn’t in the familial sphere—forgo a visit to the doctor, sell your wife, or work as a bonded laborer—all in order to make a debt payment.

Anthropologist Alain Testart distinguishes among different types of debt bondage: (1) Slavery is when insolvent debtors lose rights and citizenship and are essentially exiled with no chance to attain freedom; (2) pawning is a type of forced labor in which a debtor serves a creditor, and eventually, but not always, attains freedom after the debt has been repaid.88 Both deprive a debtor of freedom, and often pawns become slaves, as creditors add the cost of food and medicine to the outstanding debt as well as charging high interest rates.

In ancient Mesopotamia, pawning involved ruthless practices. Graeber’s research finds that a man was disallowed to sell his wife. But the Code of Hammurabi stipulated that creditors could seize a man, his family, or his slaves if he was unable to repay a debt—and force them to work. A debt contract effectively turned a person into an object or commodity to settle an account, contorting the familial sphere into the commercial one.89 Upholding one’s creditworthiness was part of maintaining honor, apparently a virtue for which anything or anyone could be sacrificed.90 Maintaining one’s reputation is vital to the gift economy, too, but the punishments in the commercial sphere are usually more severe. In a gift economy, the benefactor risks his own reputation if he treats a debtor without compunction. In the market economy, historically, the creditor could resort to cruel measures.

The Code of Hammurabi offered borrowers some protections: A debtor was to be freed after three years of bonded labor; and if a debtor died because of abuse while a bonded laborer, the creditor was punished with the death of his son.91 Over history, many leaders have tried to protect debtors. For example, in Athens around 600 BC, there was a real possibility of popular revolution—as bonded labor and slavery had become rampant. Solon, the archon of Athens, canceled debts and abolished debt slavery (but not all forms of pawning).92 He, like many overlords in antiquity, recognized the disastrous effects of too much debt: If the balance of power tilts too heavily in favor of the creditor, a whole society can come crumbling down. Debt protection, then, is also creditor protection. Let’s not upset the whole applecart.

Imprisonment for debt was also a common practice in ancient times. During the Roman Empire, a creditor could arrest the debtor for debt delinquency and haul him into court. If guilty, the debtor could land in a private jail, and after sixty days become a slave, bonded laborer, or even be killed. Though uncommon, creditors were allowed to cut up a debtor’s body into chunks commensurate to the debt owed.93 Yet Roman rulers, like those of Greece and Babylon, realized the importance of debtor protection. They ushered in public prisons, four-month grace periods for repayments, and eventually the abolition of debt imprisonment altogether.

But debt imprisonment endured. In eighteenth-century England, many debtors found themselves locked up in Fleet Prison in London, or Marshalsea Prison, which Charles Dickens mentions in his writings. One of these debtors in Fleet Prison was a trader who simply had had a bad financial year. He was dragged from his room and laid outside to face inclement weather. Though he was in poor health, the trader was beaten and abused with a sword by the warden. The next day the prisoner was tortured by having irons put on his legs. The prisoner pleaded that he would like a hearing before a court to protest such cruel punishment, yet he was taken to the dungeon, where even more irons were used to keep him in constant pain for three weeks, and he almost lost his ability to see. After many inhumane episodes like this, Parliament banned debt prisons with the Debtors Act of 1869.94

Many who fled England for America were debtors themselves, escaping the reach of creditors. However, debt prisons existed in colonial America and were a common grievance among colonists.95 Pennsylvania’s founder, William Penn, and Revolutionary War financier Robert Morris both spent time in these prisons. My native state of Georgia actually began as a debtor’s safe haven. Its founder, James Oglethorpe, developed a strong opposition to debtors’ prisons because his friend died from smallpox in one. He established the Georgia Society, a debtors’ refuge, which ultimately won a royal charter from King George II to set up the colony of Georgia. Despite efforts to stamp out debt imprisonment, it still lingered. In 1830, more than ten thousand people were imprisoned in New York debt prisons. Many times the debts were minimal. In Philadelphia, thirty inmates had debts outstanding of not more than a dollar.96 There were five people imprisoned for debt delinquency for every one put away for a violent offense. Eventually, by 1833, the federal government wised up and abolished debt prisons.97

State-sponsored debt bondage and imprisonment has declined considerably. But according to the US Department of State, even today, millions like Raju in South Asia and in other parts of the world are laboring to repay their debts, and find themselves in difficult circumstances. Sometimes they are even working to repay the debts of their deceased ancestors.98

The dark side of debt isn’t limited to the emerging world. Remarkably, in America, several states still allow the jailing of debtors, and more than five thousand warrants have been issued since 2010.99 In 2011, citizens were jailed essentially for carrying outstanding debts. Collection agencies resorted to harsh measures during the global financial crisis. One lady who was pulled over because of an ineffective muffler was arrested because she had failed to show up in court to answer for $730 in unpaid medical expenses; she wasn’t even aware that the collection agency had filed a lawsuit against her.100 Though financial debt instruments have become more complex and easily tradable, the dark side of debt has lingered since before Hammurabi’s times.

From Mind to Matter

The first part of this book serves as the intellectual foundation for the next section. The evolutionary investigation into money shows that exchange is fundamental to all organisms. Initially the instruments being exchanged were food items that served an evolutionary purpose to promote survival. But as humans gained capacity for symbolic thought, more durable commodities were exchanged. Chapter 4 is an extension of this line of thought, and it addresses the commodity form of money.

However, this anthropological investigation into money suggests that debt is our primary currency. Not every transaction is completed immediately. We do favors for each other and remember who owes us. Moreover, financial debt precedes the invention of coined money by thousands of years. Money need not be a commodity, then. We can transact in something that doesn’t have intrinsic worth, since it can still be a symbol of value. Chapter 5 is an extension of this line of thought. It addresses money as a symbol of value determined by the issuer, which is usually the government.

From the Galapagos to the Trobriand Islands, my quest to understand money started with grasping the roots of an idea. Whether using money is a function of genetics, a neural stimulant, or a behavior instilled by culture, why we exchange remains a fascinating question. But now is the time to move from why to what. To move from the mind of money, to the body of it—how it looks and feels. And how despite its changing forms, it remains a symbol of value throughout.