DRAFTING L.T.

The first things Harry Carson noticed were the rookie’s legs. They were skinny and spindly and looked more like they should be holding up a dancer, not a football player. And there were other things that bothered Carson, too. Like the fact that the Giants didn’t need him.

“Brad [Van Pelt], Brian [Kelley], and myself, we played well,” Carson said. “We had a really good defensive line in front of us. Jack Gregory, John Mendenhall, George [Martin]. We played well together. We didn’t need another linebacker, we needed a running back, and George Rodgers was the top running back.”

Even John Mara, the son of owner Wellington Mara who was practicing law at the time and not involved in the day-to-day dealings of the organization, recalled hoping for Rodgers to be the Giants’ selection.

“We desperately needed a running back, and I had seen him on TV,” Mara said of Rodgers. “I had never seen this linebacker from North Carolina everybody was talking about, I had never seen him play.”

So, when Rodgers was selected first overall by the Saints and the Giants took Lawrence Taylor, linebacker from North Carolina, the decision was met with a shrug.

“I remember feeling kind of ambivalent about it at the time,” Mara said.

Carson was also unimpressed that, when word got out that the defensive players on the roster might be resentful of a rookie coming in and making more money than some of the established veterans—there was even talk of a walkout in protest—Taylor flashed some attitude. Both he and his agent sent telegrams to the Giants the day before the draft telling them not to bother drafting him.

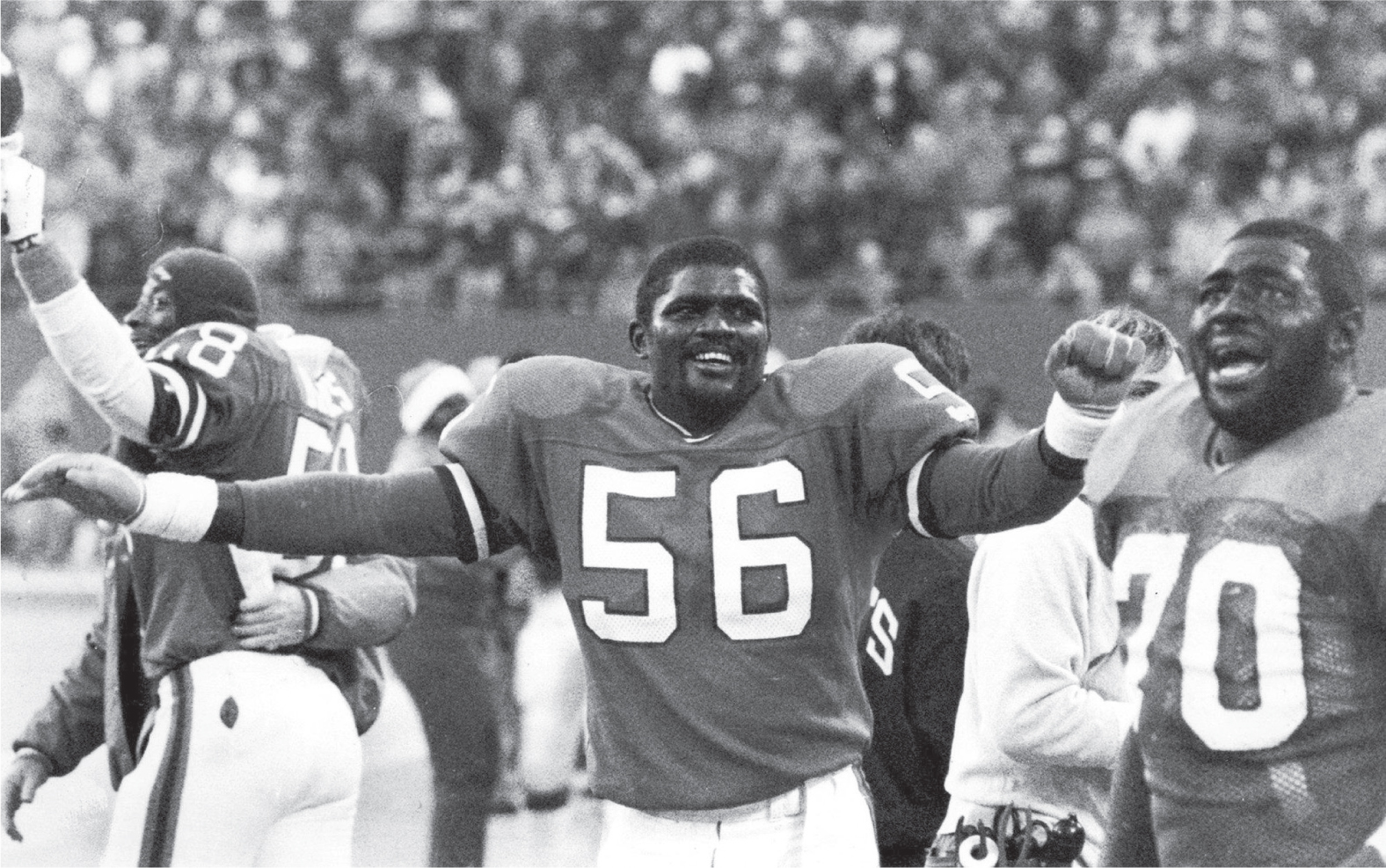

Lawrence Taylor, shown here during his rookie season, made an immediate impact for the Giants when he joined the team as the second overall selection in the 1981 draft. (Copyright © New York Football Giants, Inc.)

“If he’s picked by the Giants, he will not play for the Giants,” read the one that landed in George Young’s hands.

Young threw the telegram—which would be a priceless artifact of NFL history had it survived—in a garbage can. Head coach Ray Perkins, who’d received a similar message from Taylor himself, discarded his in the same fashion. The next day, April 28, 1981, the Giants made their selection.

Taylor apologized quickly and publicly for the telegrams.

“I don’t want to cause any problems with the team,” he told reporters after the draft. “I told Coach Perkins that it was a mistake on my part to send the telegram.”

But he still had to win over his new teammates on the field. The ones who were sizing him up when he first walked out there, wondering how those lamp-table legs would be able to function in the physically demanding world of the NFL.

“Players, they look at one another like, ‘What makes you the second pick in the draft? What makes you so special?’” Carson said.

It didn’t take Taylor long to show them and put all of the doubts and concerns and questions to rest.

“He had agility, speed, quickness,” Carson said. “When we got into the actual drills, we got to see firsthand why the Giants chose him… He went from like third team to first team before the first practice was over.”

And there he stayed for 13 seasons.

Over those next 13 seasons, the Giants would be riding the Lawrence Taylor Rollercoaster. It took them to great heights, including the playoffs in his rookie season for the first time since 1963, and a pair of Super Bowl victories. But it also caused them headaches and embarrassment, as his fast-lane lifestyle often conflicted with the team’s goals.

In 1987, he tested positive for cocaine use. The next year, he failed a second drug test and was suspended 30 days. In his 2003 autobiography, L.T.: Over the Edge, he wrote that he cheated on NFL drug tests by using urine from other players.

Carl Banks, drafted by the Giants as a first-round linebacker three years after Taylor, says there are three sides to L.T. He divides them up into the on-the-field teammate and player, the off-the-field-teammate, and then the person.

Lawrence Taylor had plenty to celebrate during his tenure with the Giants from 1981 to 1993, but there were dark times, too. (Newsday LLC/Paul J. Bereswill)

“He was an incredible teammate on and off the field,” Banks said. And for the most part, the Giants only ever saw those first two sides.

“Lawrence was fun,” Banks said. “He was a lot of fun. He was a fun off-the-field teammate. The off-the-field person? We were never invited into that world, so I couldn’t give you a lot other than what we read and the test results, obviously.”

In those days, the team would bond at weekly dinners at a nearby Beefsteak Charlie’s. Taylor, in spite of his fame and the pull of his demons, never missed a meal with his fellow Giants.

“Lawrence participated in all of it, and then when he left, us he did whatever he did,” Banks said. “He never invited anyone out into the drug world. But he was fully engaged as a teammate on and off the field. He was a participant in the process of team.”

Banks said there were times when Taylor’s behavior bled into the team, but those were mostly hijinks and not actual distractions. Like the time he showed up to a team meeting before a game against the Cowboys in handcuffs from a tryst with a woman. No one could find a key to let him loose, so the team had to call the police to unlock the steel bonds.

“As a teammate, the stuff that he used to do that was harmless like breaking curfew or whatever else,” Banks said, “he could do it better than everybody else, put it that way. Just like playing football. It wasn’t like other people weren’t doing it, he was just doing it better.”

Taylor played by his own rules. He would come into meetings late and sleep and get yelled at by coaches. He’d wake up, look at two clips of film, draw up what the defensive game plan or pass rush should be, and then go back to sleep. The coach had been there for the last hour trying to draw it up, and he would rub his eyes, say, “Ok, here’s what we need to do,” and then cut the lights off and go back to sleep.

But there was a dark side. The addictions. The recklessness. The part that went, as the title of his autobiography aptly stated, over the edge. Even after his playing days ended, Taylor continued with a hard-partying lifestyle. He did stints in rehab and was arrested several times on drug charges before getting sober.

Did that taint his legacy with the Giants? Banks paused for a few moments before answering that.

“No,” he said. “No.”

In fact, Banks suggests that all of the outside troubles actually helped make Taylor the legend he became as L.T.

“I think his legacy, that’s built into it,” he said. “The comebacks, the suspensions, the adversity, that’s all built into the legacy. In the final analysis, he was the guy who willed himself with a separated shoulder to play a game and impact a game. He was the guy who willed himself with bad ankles or whatever it was. Whatever was needed he did it. The flu. Whatever it was, he did what it takes. His will was part of the collective will of the team. He influenced that. His flaws, I think, are built into his legacy.”

However ugly Taylor’s outside life was, on the field he was beautiful. Graceful. And in a sport where few admit to being impressed, he was awesome.

“In practice, we would sit on our helmets when the drill came up where we had a linebacker having to go against a running back or an offensive lineman or whatever, and it was like watching a show,” Carson said. “He would do things on the field that we’d never seen before, and it was all impromptu. He would just think of stuff as he was going through the movements. He was the best that I had ever seen. He was like a freestyle ballerina masquerading as a football player.”

“Playing with Lawrence Taylor is the most surreal experience,” Banks said. “I’ve never played with Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, Magic Johnson. But I can imagine their teammates would probably feel the same way. With Lawrence, he saw the game totally different than anyone else. He was as brilliant a football player as he was a gifted, physical one.”

Mostly, though, it was a joy being on the field with him.

“He made everybody better,” Carson said. “And he made it fun.”

Taylor retired after the 1993 season with 1,089 career tackles, 132 ½ sacks (plus the 9 ½ he had as a rookie the year before sacks became an official NFL statistic), nine interceptions (with 134 return yards and two touchdowns), 33 forced fumbles, and 11 fumble recoveries. He also left a swath of broken and battered quarterbacks and offensive linemen, and a long stream of outrageous soundbites and ridiculously athletic highlights captured by NFL Films.

Even in retirement, he helped the Giants win one of their biggest games ever. On the Saturday before the 2000 NFC Championship Game against the Vikings, a number of Giants greats attended practice. Carson was there, Phil Simms was there, and plenty of others. Jim Fassel had to choose one of them to address the team.

“I took a big risk, a really big risk,” Fassel said, knowing that Taylor could be a loose cannon but also recognizing that even while standing on the sideline watching practice, it was impossible for Taylor to be ignored. “I had to pick somebody, and I asked Lawrence Taylor to address the team. But when he got up to talk, what he said to the team after practice on that Saturday, I couldn’t have written the speech better for him myself.”

In front of that team, with the members of his teams beside him, Taylor said: “Guys, I’m not here to tell you what we did. I’m here to tell you that we are honoring you guys. It’s not about us and what we did, it’s about what you guys did and what you are going to do.”

“Boy, I’ll tell you, that was awesome,” Fassel said. “It really set with the team.”

The next day, they beat the Vikings, 41–0.

That’s the player and the person whom the Giants remember. The one many of them didn’t even know they wanted or needed.

John Mara recalled asking George Young about Taylor after the selection was made and his indifference had subsided somewhat.

“He said: ‘Just wait and see,’” Mara said.

Young was right.

“I still have never seen anything quite like that,” Mara said. “To me, he’s the best player in our history.”