FOR THE DUKE

Hey, are you gonna keep getting caught or are you gonna score a touchdown?

That was the question posed to Tiki Barber as he came to the sideline huffing and puffing after his second long run against the Redskins that did not find the end zone. He’d opened the game on October 30, 2005, with a dash of 57 yards around the left side and then peeled off a 59-yarder in the second quarter, only to be stopped at the 1. Brandon Jacobs ran it in from there on the next play.

Barber was having one of the greatest games of his career, the Giants were cruising, but there was one glaring omission. No touchdown.

The person who posed the blunt but playful question to Barber wasn’t a coach or even a teammate. It was Tim McDonnell, one of the grandchildren of Giants owner Wellington Mara. McDonnell and Barber had been friendly for years going back to when McDonnell was a young ball boy during training camps. When Barber was a rookie in 1997, it was McDonnell who took care of Barber’s locker at SUNY Albany and ran errands for the running back. They’d stayed in touch through the years despite spending less time together. Barber even attended McDonnell’s graduation party when he matriculated from Holy Cross and was about to begin a job with the football program at Notre Dame. Now McDonnell was a 22-year-old and on the sideline of this game at Giants Stadium giving guff to the best running back in team history.

“Timmy,” Barber said, “I promise you, before this day is over, I am going to score you a touchdown. And I’m going to bring you the ball.”

It was a game the Giants knew they’d have to play all season, they just didn’t know when. Wellington Mara, their long-time Hall of Fame coowner, was dying of lymphoma, and Head Coach Tom Coughlin began the year by telling the players that they were going to be “the team of record” for Mara and coowner Robert Tisch (who was battling brain cancer at the same time). Everyone knew there was a good chance neither of the men would live to see the end of the season.

By late October, it became clear that Mara was fading quickly. The Giants beat the Broncos, 24–23, on October 23, knowing it was likely to be the final game of Mara’s life.

That Tuesday, Barber received a call from the team’s long-time trainer Ronnie Barnes, summoning him to the Mara family home in Westchester to say his goodbyes to Wellington. He quickly drove up from his place in Manhattan.

“I walked in, and it was such a somber feeling in the house,” Barber recalled. “I passed on my thoughts and prayers (to the family members). And before I left I got a chance to go sit with him, Mr. Mara.”

He was sleeping.

“I remember just looking at him and holding his hand and thanking him for being a part of bringing me to New York and letting me be a Giant. And then I left.”

Mara died later that night at age 89.

The rest of the week was a whirlwind of emotion as the Giants dealt with the loss of their beloved owner while also trying to prepare for the Redskins. On Friday, Mara’s funeral took place at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. The building was crammed with a who’s who of luminaries from the worlds of sports and business and popular culture. The team was bused to Manhattan for the service and listened to a stirring eulogy from Wellington’s oldest son, John, who had already assumed the role of team president several years earlier.

It was a gloomy, overcast gray day with a high ceiling of clouds, not atypical of autumn in New York. “The perfect day for a funeral,” Barber said.

The Giants then boarded the buses and returned to New Jersey for their practice. While they were stretching, just as Coughlin walked past Barber, those dreary clouds parted just enough to allow a stream of sunshine to reach the field.

“Coach,” Barber said to Coughlin, “that’s Wellington looking down on us.”

Coughlin gazed up at the sky.

“Yeah,” he said. “You’re probably right.”

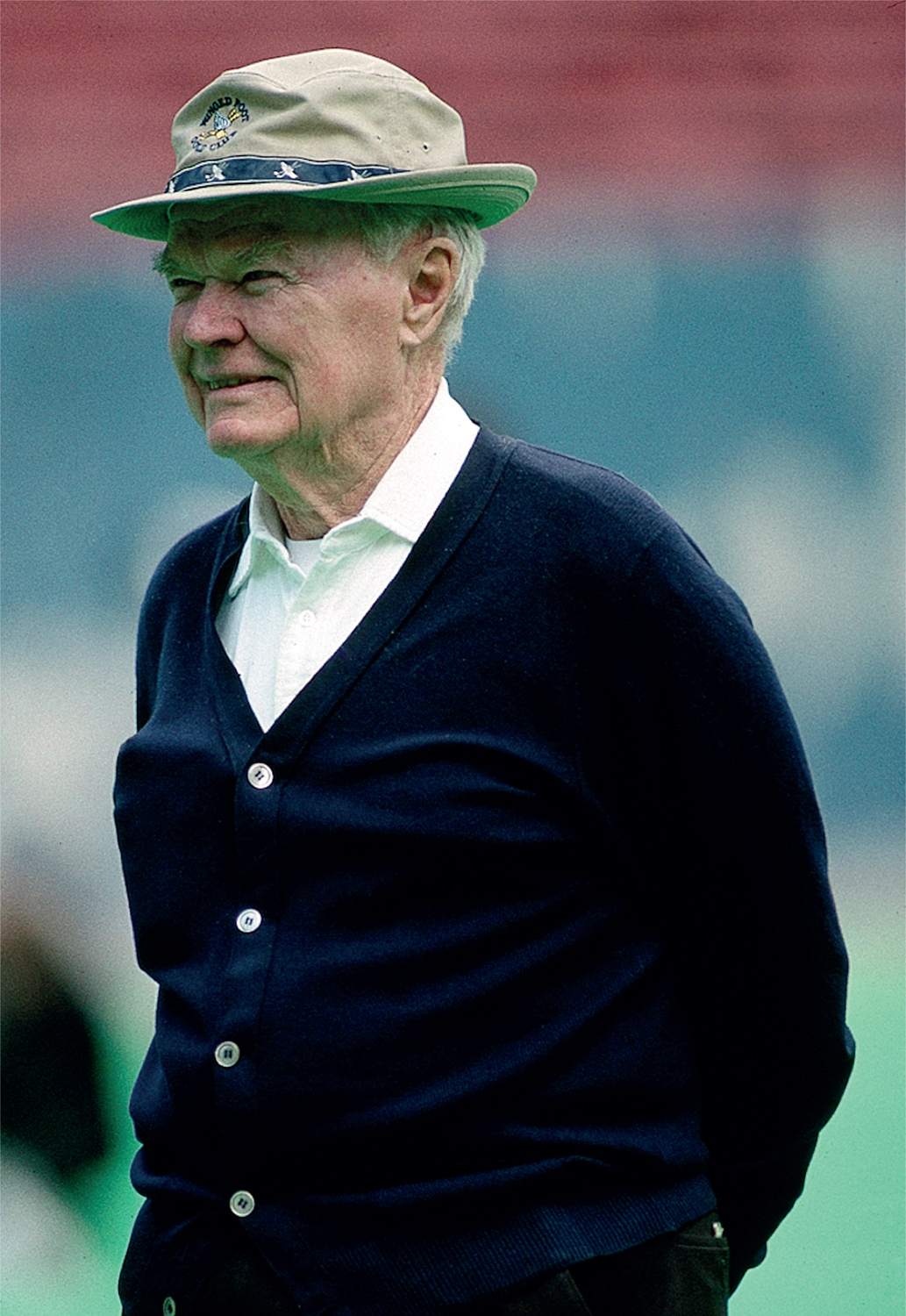

Wellington Mara was a fixture on the sideline during Giants practices and games, and his legacy lives on with his nickname imprinted on every football the NFL uses. (Copyright © New York Football Giants, Inc.)

Wellington Mara was one of the most influential figures in American sports. Named after the Duke of Wellington by his father, Giants founder Tim Mara, he was born in Rochester, New York, on August 14, 1916. He was a nine-year-old ball boy for the Giants during their inaugural season in 1925 but quickly climbed the ranks. How quickly? In 1930, five years later, Tim Mara split his ownership interest between sons, 14-year-old Wellington and his brother Jack. Wellington was the Boy King of the Giants. The Tutankhamun of his day.

After he graduated from Fordham, Wellington came to work for the Giants’ front office as treasurer and assistant to his father. In 1940, he became the team’s secretary. After serving in World War II, he returned to be named the team’s vice-president. When his uncle died in 1965, seven years after his grandfather had passed, Wellington became president of the Giants.

He played not just a huge role with the Giants, helping to assemble the teams that would exemplify the franchise’s glory in the 1950s and early ’60s with Frank Gifford, Sam Huff, Roosevelt Brown and Y. A. Tittle, but was instrumental in much of the framework that today makes the NFL one of the world’s most prosperous sports leagues. In an age when the Giants were the NFL’s biggest draw, it was Mara who championed the idea of revenue sharing from television contracts so that teams in bigger markets would not have a financial advantage over those from smaller outposts. It was a concept that probably hurt the Giants but allowed the NFL to thrive.

Wellington Mara’s memory lives on in every NFL contest. Since 1941, when Wilson became the official manufacturer of gameday balls for the league, every game has been played with the same model. Since Tim Mara played such a large role in striking the deal with Wilson, legendary Bears owner and coach George Halas thought that the model should be named “The Duke” as a way of honoring the Mara family. To this day, every official NFL football is imprinted with that nickname: “The Duke.”

The game that followed his passing was a blowout. There was no team that could have stood between the Giants and a victory in that game and thwarted their efforts to revere their beloved owner. The afternoon at Giants Stadium began with his granddaughter, Kate Mara, not yet the well-known actress she would eventually become, singing the national anthem. Fans brought signs thanking and honoring Wellington where once he had been hung in effigy from the upper deck.

The service on Friday at St. Patrick’s had been for family and dignitaries. This game was for the fans to say their good-byes.

And it started out about as perfectly as possible. Barber took that first toss to the left, and it was blocked perfectly, as if the players themselves were the X’s and O’s on the paper when the play was drawn up. More such plays continued. Barber snapped off the 59-yarder to the 1. The Giants defense was throttling the Redskins just as badly. By halftime, the Giants led, 19–0. Jeremy Shockey, the only other active Giant beside Barber who was asked to visit Wellington’s bedside in his final days, caught a 10-yard touchdown pass from Eli Manning to open the second half. By late in the third quarter, it was 29–0, and soon, after Osi Umenyiora recovered a fumble at the Washington 23, the Giants were once again on the doorstep of the end zone.

The only thing missing from making it a perfect day was a touchdown by Barber.

When the Giants reached first-and-goal from the 6, that’s when the effort to get Barber into the scoring column ramped up. He took a handoff to the left for 2 yards, then a handoff right for no gain. On third-and-goal from the 4, Barber took the ball up the middle on a draw play. All-Pro safety Sean Taylor came flying in to attempt a tackle, but Barber managed to dive over him and stretched the ball over the goal line.

Barber left the ball on the turf and blew a kiss into the air, just as he normally did after touchdowns. Then he quickly realized that this was not a normal touchdown. He went back and picked the football off the turf and carried it to the sideline as a keepsake.

But not for himself.

He immediately flipped the ball to McDonnell, the grandson of Wellington Mara, his former personal valet, who had goaded him earlier about getting caught from behind on the two long runs.

“Timmy,” Barber said, “this is for you and your family and the Duke for making me a Giant. Thank you, guys. I love you all.”

At the end of an emotional week, McDonnell said he didn’t know whether to smile or cry.

“It was everything coming together at once,” he said. “It was special. Really special.”

McDonnell is now a pro scout for the Giants. His office at the team’s facility in New Jersey, like most others in the building, is decorated with plenty of Giants regalia and a few game balls from memorable contests. Most of them are painted and written on to tell their story from various victories. But in a glass case in his office sits an unadorned football. It’s the one that Barber tossed to him during that game.

“Just the way it was that day,” McDonnell said.

The only way anyone would know its significance without asking would be to look at the sideline credential from that game, which is also in the case.

Like every NFL football since 1941, this one boasts its model name, too. Yet somehow, “The Duke” seems to stand out more on this one than the others.

After the touchdown, Barber was through. There was still another quarter left in the game, but he’d done what he set out to do. Like a sculptor who must know when to put down his chisel or a painter who needs to recognize when to lay down his brush, he’d finished his masterpiece. He had the touchdown. He’d run for 206 yards on 24 carries through three quarters and said he could have probably run for 300 if he’d stayed on the field.

“But I didn’t want to,” he said. “It was unnecessary. I don’t need to add anymore.”

That decision would prove to play a role in determining the NFL’s rushing leader when the season ended. Barber had his best year as a pro. He took to heart Coughlin’s preseason challenge about being the “team of record” for the two owners. He finished with 2,390 all-purpose yards, the second-most at the time in NFL history behind Marshall Faulk, and after he ran for 203 in the regular-season finale against the Raiders in Oakland, he had a league-leading 1,860 rushing yards. That was 53 more yards that Seattle’s Shaun Alexander had.

Alexander had planned to sit out his team’s final game that season. The Seahawks were heading to the playoffs—eventually to the Super Bowl—and he thought he had the rushing crown locked up. Then he saw Barber’s performance earlier in the day, did some quick math, and changed his mind.

Tiki Barber called his performance against the Redskins in the game immediately following the death of beloved coowner Wellington Mara “my forever Giants moment.” (Tom Berg / Staff, courtesy of Getty Images)

“He told me, ‘I saw you rushed for 203 yards and I wasn’t supposed to play, but I was like, fuck that, I’m playing!’” Barber said. Alexander took 20 carries in a meaningless game against the Packers and ran for 73 yards to finish his season with 1,880. Twenty more than Barber.

“I always tell people: ‘If I would have not taken myself out in that Redskins game, I would have had the rushing title that year,’” Barber said. “But that wasn’t important to me. It was more important to do what I had to do to pay my respects to one of the great men that I ever met.”

That Redskins game may feel like an unfinished symphony to some, but to Barber it was complete.

“I did what I set out to do, which was have my greatest day as a Giant,” he said. “That was my forever Giant moment.”