“HEAR, YE TOWNSFOLK, HONEST MEN”

It is ten o’clock at night—give or take ten minutes. The great E-bell of the Katherine Church has begun to strike the hour. Between its seventh and eighth strokes, the Parish bell begins to strike. You would suppose that the sacristan of the Parish Church had been awakened by the Katherine bell, pulled himself out of bed, and got to his bell rope just in time to avoid complete humiliation (like a man running shirtless and shoeless to a wedding to get there before the ceremony is over). But you would probably be wrong, for every night, ever since there have been two bells in Kronenberg, the first stroke from the Parish Church has come just after the seventh from the Katherine; in deference, perhaps, for the Katherine Church was once (up until the Reformation a century ago) a cathedral.

Now Kronenberg has, besides two church bells and two churches, six thousand churched souls; and a university, with a theological faculty and almost a hundred students; and a Castle, which crowns the hill on which the closely packed, semicircular town is built (a hill so steep in places that some of the houses can be entered only from the top floor); and a river at the foot of the hill, the Werne. The Werne isn’t navigable this far up from the Rhine, but its course around the flowering hill conspires with the Castle at the top, the massed gables of the timbered old houses that climb to the edge of the Castle park, and the cobblestoned lanes and alleys that gird the hillside like tangled hoops, to make of Kronenberg a picture-book town on a picture-book countryside.

The town has had its troubles, as what town hasn’t? In the half-dozen centuries past it has changed hands a dozen times. It has been stormed, taken, liberated, and stormed and taken again. But it has never been burned; its prettiness (for it is small enough to be pretty rather than beautiful) may have shamed off the torches which have gutted so many old towns; and now, in 1638, Kronenberg is always designated as “old Kronenberg,” an ancient place.

The Great War of Europe is twenty years old, but maybe it is over; the Prince of Hesse has decided to join the Peace of Prague, to drive the Protestant Swedes out of the Catholic Empire without, it is hoped, incurring submission to the Catholic Emperor in Vienna. True, Catholic France has just attacked Catholic Spain and, in alliance with Protestant Sweden, has just declared war on the Emperor. But Kronenberg has only heard vaguely about these wonderful events, and who knows what they mean? “The King makes war, and the people die”; it’s an old, old saying in Kronenberg.

Times have been very hard everywhere these last years, in Kronenberg, too; taxes and tolls always higher, men, animals, and grain taken, always more, for the armies. But the war, moving from north to south, from south to north, and from north to south again, has spared the town, except for a siege which was driven off by the Protestant armies. All in all, the Kronenbergers can’t complain. And they don’t.

Pestilence and famine recur in Kronenberg—as where don’t they?—and, where there are Jews, what is one to expect? After the Black Death of 1348, the Judenschule, or prayer-house, was burned in Kronenberg, and the Jews were driven away. (Everyone knew they had poisoned the wells, all over Europe.) A few years afterward the finances of the Prince of Hesse were so straitened that he had to pawn Kronenberg to the Jews in Frankfurt, but in 1396 Good King Wenceslaus declared void all debts to the Christ-killers. But that wasn’t the end of it, because the princes always brought the Jews back, to do the un-Christian business of banking forbidden Christians by canon law. So it was, until 1525, when the Bürgermeister of Kronenberg implored the Prince to drive the Jews out again. “They buy stolen articles,” he said. “If they were gone, there would be no more stealing.” So the Prince drove them out again; but he exercised the imperial privilege given by Karl V to keep a certain number of Jews in the town on the condition that they pay a protection tax, a Schutzgeld. If they failed to pay the Schutzgeld, the Prince removed his protection.

Those were good times, before the Great War of Europe. Times are hard now; but they might be worse (and nearly everywhere are) than they are in Kronenberg, and tonight the burghers and their manservants and their maidservants are sleeping contented, or as contented as burghers and their manservants and maidservants may reasonably expect to be in this life. So are their summer-fattened cattle and their sheep in the meadows (it is not yet cold in early November), and their pigs and chickens and geese and ducks in the barn at the back of the house; sleeping, all, at ten o’clock.

The two church bells are dissonant, the Parish bell’s A-flat ground tone against the Katherine’s E; workmanship is not what it was when the Katherine bell was cast three or four centuries ago. But it takes more than the dissonance of the bells to awaken the people of Kronenberg. It takes even more than the rooster on top of the Town Hall to do it.

The Town Hall rooster is a wonderful rooster. It flaps its wings and crows a heroic crow, once for the quarter-hour, twice for the half-hour, three times for the three-quarter-hour, and four times for the hour—and then it crows the hour. If (as it does) it begins its ten o’clock crow when the Katherine bell is finished and the Parish bell has just struck its sixth stroke, the fault cannot be the rooster’s, for the bell-ringers are human and fallible, but the rooster is mechanical. To say that the rooster was wrong would be to say that the Town Clock was wrong, and this no one says.

Now the dissonance of the two bells is as nothing to the cacophony of the rooster and the last four strokes of the Parish bell; still the Kronenbergers sleep. They sleep until their own Sesh-and-blood roosters respond to the crowing atop the Town Hall. The response begins, naturally, in the barns and dooryards near by and fans out in an epidemic descent down the whole Kronenberg hill The roosters awaken the ducks and the geese, then the pigs and the sheep; then the cattle stir and low. The house dogs are the last to be heard from, but, once begun barking, they are the last to stop.

All Kronenberg turns over underneath its mountainous feather beds. Everyone half-awakens with the dissymphony, remains half-awake until it is over, and then slips back, but not all the way back, into sleep. The Kronenbergers have yet to have their ten o’clock lullaby, the lullaby they have had, and their ancestors before them, every night of their lives, the Night Watchman’s Stundenrufe, or calling of the hours.

Every night the Night Watchman stands in the Market Place until the clatter of the bells and the animals is ended; an old pensioner in the raiment of his office, a long green greatcoat and a high-crowned green hat, his horn slung over his back, his lantern in one hand, his pikestaff in the other. Staff, lantern, and horn, Night Watchman himself, are increasingly ornamental nowadays. As he makes his hourly round, he watches for fires, which are rare in cautious, pinchpenny old Kronenberg, and for a still rarer pig broken out from a barn.

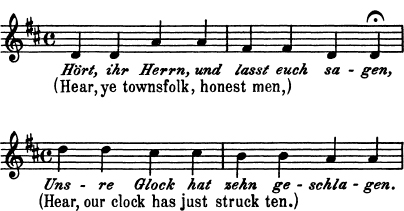

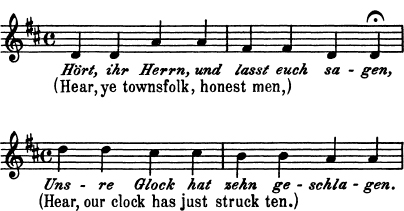

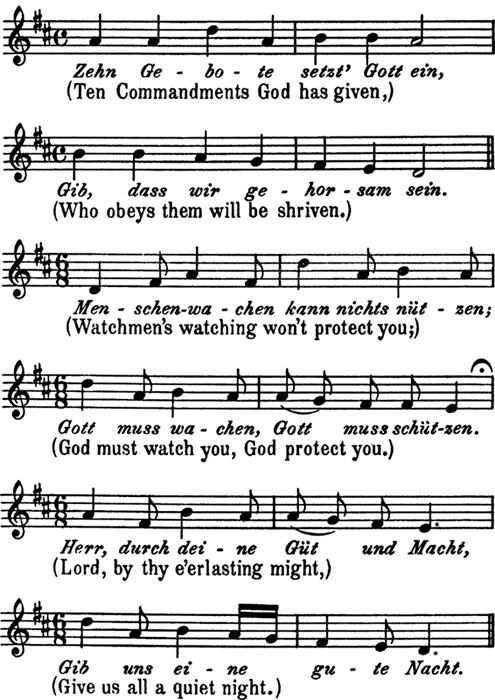

But he has his dignity, this man who, if only symbolically these days, has the community in his care; he will not compete with roosters and geese. When the last echo of the clatter has died—and not before—he puts his horn to his lips and blows it ten times and then begins his descent through the town, clumping heavy-booted on the cobblestones, singing the Kronenbergers back to sleep:

By this time, of course, the Town Hall rooster has long since crowed his one crow for 10:15.

Holding his lantern aloft, the Night Watchman goes through the town, as his counterpart goes through every town in Germany, singing this self-same lullaby from ten o’clock on. A few minutes before eleven (or after; who knows?) he is back at the Market Place, and when the eleven o’clock racket is over, he blows his horn and again makes his round. This time, instead of singing “Zehn Gebote setzf’ Gott ein,” he sings “Elf der Jünger blieben treu, Hilf dass wir im Tod ohn’ Reu” (“Christ’s eleven served him true, May we die without one’s rue”); at twelve he sings “Zwölf, das ist das Ziel der Zeit; Mensch, bedenk die Ewigkeit” (“Twelve sets men from this day free; Think ye of Eternity”); and at one he sings “Eins ist allein der ew’ge Gott, Der uns trägt aus aller Not” (“One alone is always there, He who lifts us up from care”).

From one o’clock on, until dawn, the Night Watchman sings no more. His song has no more stanzas and certainly no more listeners. Each hour, after the bells and the beasts subside, he blows his horn and makes his round, and the Kronenbergers sleep. Should one of them awaken and see a light outside, he knows whose it is and sleeps again. The town will be up at dawn; the day ends at dark. Everyone works, nobody reads, and tallow, except in the university, the hospital, and the Castle, is burned for only an hour or two to feed house stock and mend harness or stockings by.

Just outside the Town Wall, where the toll road along the Werne enters the town at the Frankfurt Gate, stand a half-dozen new houses around a burgeoning square called “Frankfurterplatz.” The town is getting bigger, overflowing the new wall of two centuries ago as it has overflowed each successive ring of walls that protected it. The days when the town hugged the Castle for protection are over; this is the middle of the seventeenth century of Christianity, and men may live outside the walls without much danger.

At the corner of Frankfurterplatz, where a wide, uncobblestoned road runs west outside the wall and along it, a nameless road known as the Mauerweg, is the new inn, the Jägerhof, the Huntsmen’s Rest It is a fine two-storied place with a commodious dormitory above, a public room and a private room (or clubroom) below, and the innkeeper’s family quarters in back.

Tonight the lights are burning late in the public room of the Huntsmen’s Rest. The old soldiers, the Home Reserve company, are celebrating with a stein of beer or two the fifteenth anniversary of the liberation of the homeland from the shackles of Vienna. The Home Reserve company are patriotic Hessians, of course, but first and last they are Kronenbergers, and it was fifteen years ago tonight that the siege of Kronenberg was lifted. A great event for the old soldiers, and a great anniversary.

It is after midnight when, with two steins of beer or three or four inside them, they leave the Huntsmen’s Rest, some of the more patriotic old boys bent on continuing the celebration. The innkeeper does not want to get into trouble with the old soldiers or the authorities, and the instant the soldiers are gone he comes in from the back, snuffs out the lights, and goes to bed.