‘New Zealand is an historian’s paradise: a laboratory whose isolation, size and recency is an advantage, in which grand themes of world history are often played out more rapidly, more separately, and therefore more discernibly, than elsewhere.’

—James Belich, Making Peoples

Although it has been a long time, I still remember looking for New Zealand in my parents’ atlas when they told us children that they were thinking of emigrating from Switzerland to New Zealand. It was Knaur’s Atlas, a German edition that had been published before the end of the Second World War, and Hitler’s and Mussolini’s conquests were incorporated in the redrawn maps of Europe and Africa. New Zealand was not easy to find. It was on one of the last pages of the atlas, and on the same page with Australia. It looked tiny!

Measured against the vastness of the Pacific, and against its neighbour Australia (which is about 29 times the size of New Zealand), the country does indeed look small. But it is all a matter of perspective. With its land area of more than 268,000 sq km (103,500 sq miles), New Zealand is a bit larger than the United Kingdom, a bit more than two-thirds the size of Japan and almost three times the size of South Korea.

It is a long country. The two main islands and Stewart Island to the south extend over 1,600 km (994 miles). This roughly corresponds to the distance from Berlin to Moscow or from Hong Kong to Calcutta. It is also a country of mountains and rolling hills. The Southern Alps (named after the European Alps by their Austrian explorer) form the backbone of the South Island with Mount Cook, the highest mountain in New Zealand—at 3,764 m (12,400 ft) at its peak. The centre of the North Island is dominated by three volcanoes: Ruapehu, Tongariro and Ngauruhoe. A fourth volcano, Mount Taranaki, sits in solitary splendour in the Taranaki province, on the west coast of the North Island.

Apart from four large volcanoes, there are dozens of smaller ones. White Island, off the eastern coast of the North Island, still smokes on the horizon when you look out to sea from Whakatane. New Zealand’s largest city, Auckland, has about 50 (hopefully extinct) volcanoes dotted throughout the city.

The youngest volcano, Rangitoto, erupted a mere 600 years ago and is now an island in Auckland Harbour. I have walked on it and found that, while it is covered in vegetation, it still has a very thin layer of topsoil. Much of the island is covered in black basalt rocks.

Beautiful lakes are also a feature of both the South Island and the centre of the North Island, where you find the largest of the New Zealand lakes, Lake Taupo, occupying 606 sq km (234 sq miles) of a volcanic crater. The eruption that formed the crater is probably the world’s largest volcanic eruption in the last 7,000 years and occurred about 1,800 years ago. Historians in China and Rome recorded details of deep red sunsets and darkened daily skies from the ash that was hurled 50 km (31 miles) up into the atmosphere. The resulting lake is about the same size as Singapore.

Map of New Zealand showing the regions as well as major towns and cities.

While we are talking about eruptions, New Zealand is infamous. The New Zealand Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences records about 14,000 earthquakes every year in and around New Zealand. Most of them are too small to be noticed, but between 100 and 150 can be felt at least somewhere in the country, every year. The reason for all this shaking is due to the movements of the Pacific and the Australian plates grinding against each other. The first earthquake that I experienced was memorable because I almost missed it. I was outside our farmhouse when suddenly my mother and sister came running out, claiming they had felt the house shake. I had felt nothing because I was outside, but when we went back in, we found some crockery that had fallen out of the rack and crashed to the floor.

Handy Advice

In case you need advice about how to act in earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, the Ministry of Civil Defence instructions are printed inside the back cover of the ‘Yellow Pages’ volume of the New Zealand Telephone Directory. In the event that you don’t have a telephone directory handy when a quake strikes, the basic rule is to stay indoors and take cover under a sturdy table.

Wherever you are in New Zealand, you are never far from the sea. I live in the inland city of Hamilton in the North Island. From here, it takes 45 minutes to drive to the west coast, and a bit over an hour to enjoy the beaches of the east coast. Young people in Hamilton who are interested in surfing don’t have to wait for a suitable wind. When it blows from the west, they drive to Manu Bay in Raglan, some 48 km (30 miles) west of Hamilton, to experience the world’s longest and most consistent left-hand break. This break, which was featured in the 1966 cult classic film, Endless Summer, attracts surfers from all over the world. When the Raglan waters are smooth because there is an easterly wind, they simply drive over to Mount Maunganui on the east coast where there is bound to be a good surf running as long as there is wind to make the waves, of course.

The south of the North Island and the whole South Island are situated in an area that is known as the Roaring Forties. This area is characterised by strong westerly winds, which old sailors took advantage of to drive their ships from New Zealand towards Cape Horn on their journey back to Europe. Wind conditions however are usually moderate, although they may change more frequently than in many other regions in the world. Some parts of the country experience more breezy conditions than others, such as windy Wellington.

I used to fly to the capital fairly frequently and, as far as I am concerned, Wellington has one of the most exciting airports in the world. There, landing sideways seems to be a speciality of the Air New Zealand pilots. It is the only airport where, sitting in the rear of the aircraft, I have actually watched the cabin flex sideways after takeoff because we were buffeted by violent wind gusts. It has not deterred me from visiting Wellington. New Zealand pilots are superb, and I have absolute confidence in them. (Just in case you think that this confidence is misplaced, by the time you read this, I am sure I will have flown into and out of Wellington several times with lots of exciting bumps but no mishaps!)

While there clearly are variations in climatic conditions between the north of the North Island and the southern extremity of the South Island, the climate is generally described as temperate. There are parts of Northland that never experience frosts, even at night in winter. The Alpine regions of the South Island, on the other hand, can get as cold as –12°C (10°F) in winter. The average temperature in the northern part of New Zealand is 16°C (61°F), while in the south, it is cooler at 10°C (50°F).

Of course, one of the climatic features of New Zealand is that, because it is in the Southern Hemisphere, the seasons are reversed. That means that when it is coldest here in July, North America, Europe or North Asia can be sweltering in heatwaves. This also means that shop windows adorned with Christmas decorations and artificial snow will fail to convince the avid European traditionalist that it feels like Christmas when outdoor temperatures are often in the high twenties (low eighties) in December. The hottest months in New Zealand are January and February.

New arrivals in New Zealand have described its weather as unpredictable. In many climates, you can expect the weather to conform to certain patterns. The monsoon rains will come in their appointed season (more or less!), or during the dry season, you know that it will not rain for quite some time; but not so in New Zealand. The weather will change, sometimes several times a day. While there are days and weeks when it is fine, particularly in late summer, days and weeks of just rain or cloud are comparatively rare.

One of the major attractions of New Zealand is that it is a very beautiful country. It is clean, green and has ever-changing scenery, ranging from coastal panoramas to rolling hills, volcanoes, thermal areas, bush (native forests), pastoral landscapes, glaciers, mountains, lakes and rivers. Every visitor I have talked to has commented on this. Because all this wealth of scenic beauty is in a comparatively small country, travel is never boring; the landscape (just like the weather sometimes!) changes every hour or two.

The landscape is overwhelmingly rural. Flying over it, you will find that human beings have not yet had the impact on it that they have had in other parts of the world. There are still areas of rugged bush and untouched valleys and ravines. This is a marked contrast to flying over, say Europe, where forests and fields have straight edges. Another contrast is, of course, that in Europe and many parts of Asia, you can find a town or village every few kilometres; in New Zealand towns are far apart. I have often marvelled at the work the early European pioneers did to build the network of roads that serves these scattered, small communities.

Five cities in New Zealand are considered ‘major’, and even these are small by world standards. Only one, Auckland, home to a third of New Zealand’s population, has more than a million inhabitants. You will find that the New Zealand media often talk about the ‘four main centres’ by which they mean Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin. Hamilton has recently surpassed the population of Dunedin, but old habits die hard and Dunedin continues to be referred to as one of the four main centres. Wellington is the capital of New Zealand and therefore contains the head offices of most ministries as well as foreign embassies.

The Maori people describe themselves as the tangata whenua, the people of the land, and they are the original settlers in New Zealand. The first non-Polynesian settlers along the shores of New Zealand were sealers and whalers. Many of these seafarers took Maori ‘wives’ and their offspring would be the earliest New Zealanders of mixed lineage. With the arrival of increasing numbers of traders and permanent settlers, intermarriage between Maori and Pakeha (Europeans) became more common. Most Maori today will tell you of a European forebear in their whakapapa (genealogy), and many of them are proud of their European tupuna (ancestors).

The sealers and whalers were followed by missionaries, agriculturalists, explorers, merchants and adventurers. In 1837, the New Zealand Association was formed in England, becoming the New Zealand Company in 1839. The organisation aimed to colonise New Zealand in accordance with the principles of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, an English theorist. Wakefield sought to establish a British colony in New Zealand based on the English social system. Canterbury is considered the most successful of such settlements.

The British government took a growing interest in New Zealand, and more Europeans settled in the country. By 1839, there were about 2,000 Pakeha in New Zealand. The rapid growth in the Pakeha population alarmed Maori chiefs and tensions escalated. The compromise between the British government and the Maori chiefs culminated in the Treaty of Waitangi, signed on 6 February 1840, at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands. Those Maori chiefs who signed on behalf of their tribes (not all of them did!), ceded sovereignty to the British Queen, who in turn granted them the status of British subjects with all the rights and privileges that came with it. The Queen guaranteed the Maori possession of their lands, fisheries and other possessions. To prevent unscrupulous purchasers from exploiting the Maori, land was to be sold directly to the Crown.

In the same year, the first New Zealand Company settlers arrived in Port Nicholson (today’s Wellington) and founded the first settlement. More settlers followed in the next few years, especially between 1840 and 1860. The influx of European settlers pressured the colonial administrators of New Zealand to make more land available. The Maori population, feeling threatened by the ever increasing number of Pakeha agitating for more and more land, began to refuse to sell more land. Tensions mounted and erupted in wars in the North Island in the 1860s.

The Maori had reason to feel threatened. The Europeans had brought with them not just ‘civilisation’, but also firearms, alcohol and diseases against which the Maori population had little or no immunity. With Maori arming themselves with firearms instead of traditional weapons, intertribal raids resulted in more deaths and casualties. The Maori population plummeted as a result of these wars and, above all, disease. Many settlers assumed that the Maori race was dying out. They were wrong. Although it took years for the Maori to regain their numbers and morale, today, about one in seven people in New Zealand are of Maori ethnicity.

Attempts have been made to address the injustices perpetrated in the 1860 wars and their aftermath, particularly with regard to land, as we shall see in the next chapter.

One of the many positive aspects of New Zealand is that it is virtually free of dangerous animals. There are no tigers or lions, snakes are unknown, and apart from a couple of varieties of poisonous spiders that prefer to scuttle for safety when a human approaches, the land has no animals or insects to be afraid of. If the tourist brochures describe New Zealand as ‘paradise’, it cannot be the Christian or Jewish Garden of Eden because that one contained the snake that tempted Eve. You will be completely safe from animals if you want to sleep out in the New Zealand bush.

The sea, however, is another matter. Sharks are sometimes known to attack an unwary swimmer and stingrays have injured people who accidentally trod on them, but such incidents are rare. Occasionally during summer, some swimming beaches are infested by a type of jellyfish that can cause unpleasant stings.

New Zealand is not only safe from animals that pose a threat to human life, it was a safe environment for birds as well, that is, before human settlement began. Apart from two species of harmless bats and the seals along its shores, it had no native mammals. All of them were introduced by human settlers, beginning with the kiore, the Polynesian rat that was brought along by the early Maori.

The original fauna of New Zealand consisted of birds. Foremost amongst them is the kiwi, a species of flightless birds that has become a New Zealand icon. Kiwis lost their ability to fly because of the absence of natural predators in the isolation of New Zealand.

A Unique Bird

Kiwis, incidentally, are the only birds in the world that have nostrils at the end of their beaks, enabling them to smell out worms in the soil.

Also saved by New Zealand’s isolation is the tuatara, a small reptile species that has survived here for many millennia unchanged since the time of the dinosaurs.

The Europeans settlers introduced further mammals into New Zealand, and the story of their introduction reads very much like a version of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, in which the young lad who used his master’s powers to get a bucket to fetch water from the public fountain, forgot the formula to stop the bucket and inadvertently flooded his master’s house. Captain Cook had already brought pigs and goats to New Zealand. The 19th century settlers not only introduced domestic farm animals but also deer, pheasant, opossum, rats and even hedgehogs.

Rabbits were introduced and initially failed to thrive, particularly in the South Island. Once they took hold however, they soon became a pest because they multiplied, well, like rabbits. Farmers introduced stoats and weasels to try to control the rabbit population. The native birds would have helped control the rabbit population, but their habitat was severely reduced when large tracts of forests were cleared to make room for farmland. Furthermore, pests such as flies, fleas, cockroaches, earwigs and other insects were introduced, by sheer carelessness, into the ecosystem and they multiplied rapidly, uncontrolled by the reduced bird population. In the 1860s, these insects became so numerous that a huge army of caterpillars crossing a railway line to attack a barley field actually stopped a train. The track was on an uphill grade, and the wheels of the locomotive lost traction on the rails. The cause of the slippery rails? Thousands of crushed caterpillars! The train managed to get going again by having sand on the tracks, but during the delay, many caterpillars had boarded the carriages and were thus carried to new parts of the country to further spread and multiply. One measure to attempt to control the insect population was the introduction of European birds, which today are part of New Zealand’s bird population.

The New Zealand authorities are still working on containing the damage done by the indiscriminate introduction of foreign animals. Opossum and rabbit control cost millions of dollars. Offshore islands have been rid of goats and rats to allow the natural flora to regenerate and the indigenous birds to re-establish themselves. Deer are now farmed under controlled conditions, and a thriving industry has developed around them. There are now about 1.6 million deer being farmed on more than 4,000 farms throughout the country—about half the world’s farmed deed population. New Zealand is the major world supplier of venison today.

One of the success stories is the introduction of trout into New Zealand lakes and rivers. Brown trout were introduced from Tasmania, and Rainbow trout were brought in from California. To prevent poaching, free-run trout cannot be sold, so you will have to get your own gear and catch them yourself. The licences are inexpensive, and catching trout is as much fun as eating them. (Incidentally, while there are limits on the number of fish you can take, recreational fishing at sea does not require a licence in New Zealand).

If the fauna is unique, so is the flora. Eighty per cent of New Zealand’s flora is unique to this country. The leaf of the giant tree fern has become one of the icons of New Zealand. The most impressive representative of the New Zealand forest is the majestic kauri. The tree has a long, straight trunk, branching out only near the top. The wood from the kauri tree was used for making masts and planks for ships. In the 19th century, forests were stripped of many kauri trees. The kauri is a slow growing tree and, while it is now protected, it will take a long time for them to reestablish themselves. The average kauri takes about 200 years to mature. The largest known kauri in New Zealand, Tane Mahuta (Lord of the Forest), has a circumference of over 13 m (43 ft) and an overall height of 51.5 m (169 ft). It is estimated that it is about 2,100 years old.

New Zealand artists and artisans make small bowls and other small wooden utensils out of much older kauri wood called ‘swamp’ kauri. This refers to the timber from trees that were felled, possibly by volcanic activity, and then buried in peat swamps about 50,000 years ago. After the wood has been dried out—a delicate process that can take several years—it is made into attractive and unique souvenirs.

While the early Maori settlers brought with them yam and kumara (sweet potato) to supplement their diet of birds and seafood, the European colonists introduced many plant species to the land. For example, gorse, which is grown in Europe as a decorative hedge plant, has become a serious weed that has, for the past 100 years, taken over thousands of hectares of productive land. Gorse is also expensive to remove and control. Other introduced species, such as the European pine, pinus radiata, have proved more useful. The European pine trees have been planted to become huge forests, actively supplying a major New Zealand industry—timber.

Another import that is easily mistaken for a native New Zealand plant is the kiwi fruit. This brown, fuzzy fruit with its bright green flesh and decorative star-shaped seeds is actually a native of China. The seeds were brought to New Zealand in the early 20th century and planted in Wanganui in 1910. Horticulturists improved it over time, and it thrived in the volcanic soil of New Zealand. When I arrived in New Zealand, it was known as the Chinese gooseberry, and most home gardeners had a vine or two in their gardens. After all, they were tasty, decorative, and loaded with vitamin C. Although small quantities had been exported earlier, the 1970s marked an upswing in exports, during which new varieties were developed. Kiwi fruit soon became the darling of the New Zealand export fruit industry. It is now grown all over the world where the climate is right, but while I am, of course, totally unbiased, I still think that the New Zealand kiwi fruit is by far the best.

Sheep graze on one of the many farms found throughout New Zealand.

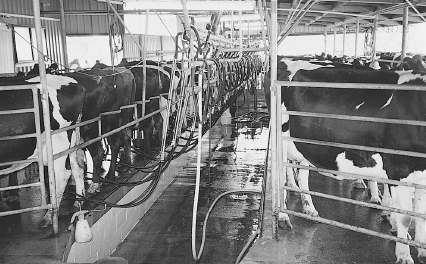

In New Zealand, the largest export is dairy products, followed by meat and meat products.

A few years ago, I was travelling in Finland and had spent some hours on a train before arriving at my destination rather late. After I had settled into my hotel room, I went down to the restaurant for a late dinner and found to my delight that there was lamb on the menu. I ordered it and found that it was superbly well prepared. When the waitress came to clear away my plate, I told her that I had been very impressed with the lamb. She adopted a lecturing stance and informed me sternly that the lamb meat had been imported from New Zealand. “That’s where the best lamb in the world comes from, you know!” I told her how much I agreed with her and the next evening, ordered reindeer. After all, the best reindeer comes from Finland!

If we add the categories of wool, fruit and vegetables and other agricultural and seafood products, we find that primary produce makes up more than two-thirds of New Zealand’s total exports. If this conjures up the picture of New Zealand as a giant farm, this is not too far from the truth, with half of the useable land in permanent pasture, and another one-quarter in forest and woodland. Nevertheless, an astonishingly high proportion of the population (86 per cent) lives in cities. What this tells us is that farming in New Zealand is very efficient, and it is not surprising that in many ways New Zealand farmers, with their ingenuity and Number-8-wire mentality (see page 33), have led the world in the mechanisation of agriculture.

Today, the small farmer-owned dairy farms are beginning to give way to larger farms often owned by absentee owners who live in town. An employed manager and several workers operate these farms. In 1916, the traditional farming couple milked about 26 cows per day. This figure has doubled in the last 20 years. The average New Zealand dairy herd size now is 351 cows, and larger farms are milking 500 cows per day.

But enough of animals. Perhaps we should take a bit of a closer look at the people that inhabit the islands of Aotearoa/New Zealand.

A milking shed on a dairy farm.

Because of its history as a British colony, New Zealand is a constitutional monarchy under the Westminster system. Although it is just about as far away from London as you can get, the British Queen, Elizabeth II, is also queen of New Zealand. She is represented in New Zealand by the Governor-general, and like the queen, her representative remains outside the cut and thrust of politics.

While New Zealand is still a constitutional monarchy, I am not sure how much longer that will continue. The former prime minister, Helen Clark, has made it quite clear that in her view, New Zealand will become a republic in the future. In voicing this view, she was really only expressing the view of an increasing number of Kiwis. A good indicator is public reaction to royal visits that take place from time to time. The earlier visits of Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh used to bring the country to a halt. People lined the route of the royal progress with flags; thousands turned up at various events where the queen would be present. Her every move and her every speech became front-page headline material in the New Zealand newspapers. In contrast to this, the most recent visit in 2002 was low-key. People knew the queen was in the country, but the visit no longer stirred up mass enthusiasm. The crowds were friendly but much smaller, and the headlines were more restrained. There still are many sincere and enthusiastic royalists, but their number is dwindling, and it is possible that the time when New Zealand will cut its ties with the British monarchy may not be too far away.

New Zealand is governed by its parliament, the House of Representatives. Members of parliament are elected by eligible voters (all citizens and permanent residents over the age of 18) for a three-year term. Parliament makes legislative decisions and supervises its administration and allocates funds to run New Zealand ministries, government departments and other agencies. These are known as the ‘Public Sector’. All members of the parliament are elected by the ‘mixed member proportional system’ (MMP). This system is also used in Germany and gives each voter two votes; one for the member of parliament and one for the party. The main decision-making body in the parliament is the cabinet, presided over by the prime minister.

This building houses the Hamilton District Court.

Many New Zealanders enjoy discussing local politics and can get quite impassioned about it. If you read the local papers, you will soon become familiar with the issues that are of burning concern to New Zealanders. If you are a newcomer, it may be wise to spend some time as a listener and spectator before expounding your own views, particularly if they concern local issues. As I said, some New Zealanders have strong feelings about political issues, and they may resent a ‘newcomer’ weighing in with their opinions, particularly if they don’t agree with them.

The judicial system is independent of the government. There are three types of court in New Zealand. The lowest, in terms of its jurisdiction, is the District Court which includes the Family Courts (for family and marriage disputes), the Youth Court and the Disputes Tribunal. The District Court deals with civil cases up to NZ$ 200,000 and criminal cases. It also regulates business activities.

The High Court deals with serious criminal cases, major civil cases and some appeals from the District Court. Finally, there is the Court of Appeal that deals with appeals from the High Court and cases after jury trials in the District Court. Up till 2004, the final appeal could be made to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. The newly formed Supreme Court of New Zealand, which replaces the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, commenced hearing cases in July 2004.

And this is the big picture, the environment in which business and society operate in New Zealand.