Many hundreds of years ago, so the Maori, the original Polynesian inhabitants of New Zealand, tell it, a young man called Maui went fishing with his four older brothers. Somehow he managed to persuade them to go much further south than usual and finally chose a spot where they would lower their hooks. He had a fishing line, but neither hook nor bait, and his brothers refused to let him have any, so he used the jawbone of his grandmother, Murirangawhenua, as a hook and baited it with blood obtained by punching his own nose. The magic hook and the irresistible bait worked wonders. Maui landed an enormous fish; the North Island of New Zealand! This is why one of the ancient names for New Zealand in the Maori language is Te Ika a Maui—‘the Fish of Maui’. It is one of many names for the beautiful islands in the south of the South Pacific, and all of them reflect an aspect of the country’s history. The myth tells us that Maui returned to his homeland, the mythical Hawaiki, and gave his people directions to find what he called Tiritiri o te Moana—the Gift of the Sea.

The first navigator to come to New Zealand named in Maori tradition was Kupe. He explored the coast of the North Island and was the first to sail through the strait that divides the two main islands. According to some traditions, Kupe also went to the South Island. He left New Zealand from a harbour on the west coast in the north of the North Islands which was named Hokianga nui a Kupe—the Great Returning Place of Kupe. This name has remained on our maps in the abbreviated form of Hokianga. Another poetic name which goes back to the early Polynesian navigators and which is often used as an alternative name for New Zealand is Aotearoa—the Land of the Long White Cloud.

The first European navigator to reach and name New Zealand was Abel Tasman. He had been sent by the Dutch East India Company in 1642 to find the hypothetical southern continent full of fabled riches. He set out from Batavia, today’s Jakarta, and found New Zealand instead, naming the country after the Dutch province of Zeeland in the Netherlands.

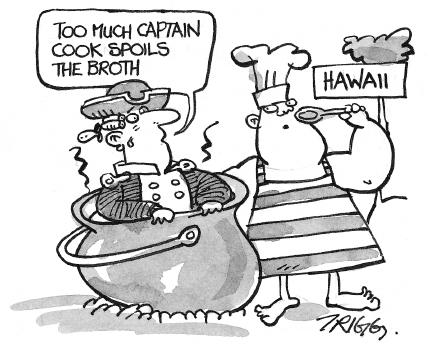

Seeing that Tasman had not found any gold, interest in New Zealand was not strong, and it was over a hundred years later, in 1769, that Captain James Cook came from England on his ship, The Endeavour. He visited the islands and proved once and for all that they were just large islands and not the great southern continent whose existence had been assumed by the scholars of his day. Cook charted the islands, both on this voyage and on two other return voyages several years later. During his visits, he added many names to the map of New Zealand. The name of the country, however, remained New Zealand, and today it is often referred to as Aotearoa/New Zealand. In 1779, Cook, the brilliant navigator and one of New Zealand’s heroes, met an untimely death. He was killed in an altercation with the local people on the island of Hawaii.

The encounters between the early explorers and the original inhabitants were not always peaceful. Part of the reason was that they did not know each other’s language and culture. A number of unfortunate incidents, some of them resulting in the deaths of some of the participants, can be attributed to misunderstandings arising from this ignorance.

Many millions of people have followed in the wake of the first navigators and settlers. Some of them have stayed, some have returned after a visit of some weeks, months or years. Most of them don’t travel by boat any more; they arrive by modern aircraft. And most of them are not totally in the dark about what they are going to find once they arrive here. New Zealand has been well and truly charted, and all you need to do is to study the chart or guide before setting out. There are plenty of books about New Zealand, beginning with the record of the early Polynesian migrations and the journals of Captain Cook and the early explorers. Some of them are listed at the end of this book.

This book is designed to help the modern-day navigators, explorers and settlers to find their way in modern-day New Zealand. It will give you the information that the early travellers and many of those that followed them did not have and had to find out the hard way. Travel is always an adventure, and travel to an unknown destination is an even greater adventure. This book is designed to help you obtain as much pleasure and profit as possible from the adventure of visiting Aotearoa/New Zealand. Welcome and kia ora tatou.

Culture shock, and its associated condition, homesickness, are two related problems that most travellers have suffered to a greater or lesser degree ever since there have been travellers. So you have decided, or your boss or partner has decided on your behalf that you should travel to New Zealand. You may not even know exactly where it is, what kind of people live there, what language they speak, what food they eat? Here is what you can do to maximise your chances of getting culture shock.

Firstly, assume that everything in New Zealand will be like it is where you are now. If you have servants in your household, gardeners, drivers, assume that you will have them in New Zealand. Assume that the food will be exactly like it is where you are now. It will have the same ingredients, it will have the same taste, and you won’t even know you are in a different culture. Also assume that the people will be the same. They will know how to behave towards you because you will treat them just as you treat the people around you in your home culture.

Secondly, assume that everything will be exactly how the tourist brochures have described it. Assume that the skies will always be a deep azure blue, that clearly there never is any bad weather, that there will be lots and lots of eager people waiting to cater to your every whim (for a very reasonable price!), and that there are flocks of clean and sanitised sheep grazing on Auckland airport in between takeoffs and landings. Also assume that friendly Maori in grass skirts will conduct you around boiling mudpools anywhere in New Zealand, unless there are snowcapped mountains and volcanoes where you will go skiing and mountaineering. Assume that there will be an endless round of extreme sports, that New Zealanders spend most of their time roaring up and down rivers in jet boats, hurling themselves out of aeroplanes or diving head first from a bungee jumping platform from a great height, or doing daredevil stunts on surfboards on the breaking faces of gigantic waves.

Finally, assume that while everybody else you know has suffered from culture shock and the associated homesickness, you are totally immune to both. You are going to be totally unaffected because you are not expecting any major differences between the culture you are in now and New Zealand culture, and anyway, the tourist brochures have told you that the sun always shines in New Zealand, that life here is one big round of excitement, fun and entertainment, so how on earth would you encounter culture shock. You are the invincible traveller!

You will have noticed that I did not say ‘if’ it strikes, but ‘when’ it strikes. There are degrees of culture shock, and not everybody is affected to the same degree. But it will strike, and the more immune you may think you are to culture shock, the harder it will strike because in addition to culture shock and homesickness, you will also be shocked by the realisation that you were not the invincible traveller after all. But fortunately there are ways to cope with the shock, and here are a few strategies to help you to do so.

It is important that you recognise culture shock when it strikes. I did not recognise it when I first arrived in New Zealand, and yet it struck on the second day. In my home country, Switzerland, I had been used to a modern, clean, very efficient and comfortable rail system. After a sleepless night in an ancient carriage on the express train from Wellington, we were met at Frankton Station by an old farm truck that was to take us to the farm that my parents had bought. I still vividly remember standing on the station platform waiting for the truck, watching primitive double-decker sheep wagons full of smelly sheep being shunted around, getting wet in the frequent showers that lashed the station on that November morning and staring gloomily into a bleak cityscape that seemed to consist only of factories and sooty workshops.

I now realise that I was quite depressed at the time and I now also realise that depression is one of the signs of culture shock. It can strike at any time. It can strike in the first day or two, as it did with me. You arrive, and find that the surroundings are totally different from what you expected, or that the arrangements have somehow unravelled and you hastily have to find alternatives. Or else, the arrangements work fine but are not satisfactory. Many years later, I remember moving to a different country with my family for the purpose of a short sabbatical and renting an apartment before leaving New Zealand. When we arrived, it turned out that the apartment was miles out of town and the nearest shop was a 45-minute walk away. In addition, it was winter, with daylight only between 9:00 am and 3:30 pm and bitter cold. Enough to make you depressed even if you lived there!

Sometimes, culture shock strikes later, when all the excitement of arrival and settling in has subsided and the routine of everyday life shows up flaws in what you had at first thought was a brilliant country. You begin to see and be irked by the less desirable aspects of the new culture. Some people become almost obsessed with them and in their minds they become exaggerated, just as the good points of the country they left become also magnified.

If you are depressed and find yourself thinking all the time of how much better everything was at home, you are suffering from culture shock. Also, if you continually brood on the question whether it was really a good idea to come to the new country, you may be suffering from culture shock. Fortunately there are things you can do initially to minimise it and then to cope with it.

Firstly, before you set out on your travels, get as much reliable information about the country that you are going to visit. Don’t be taken in by tourist brochures. They have one purpose only: to sell the country and to entice as many people as possible to come and visit. So they will paint a rosy picture that may have some connection with the reality that you will encounter, but it is important that you get balanced information that goes beyond the glossy booklets. This book will give you practical and balanced information as well as pointers to where you can get more. These days, the Internet will often have up-to-the-minute figures. This is the reason why I normally do not give prices. You will be able to get the most recent ones from the websites listed in the Resource Guide at the end. But make sure that you get as much information as you can, check it against other sources, and be aware that different publications have different aims. If you know people who have been to New Zealand, go and talk to them. But beware! Some of them may have been in the country as tourists and may not have lived in it for any length of time. So again, you may be able to get valuable and helpful information from friends and acquaintances, but cross-check your information.

Here is a small example of how easy it is to get wrong information. When we were thinking about immigrating to New Zealand, a Swiss who had done so and was back in Switzerland came to visit us one evening to talk about his new adopted country. He insisted that there were absolutely no flies in New Zealand! We believed him, of course; after all he had lived there and was the expert. He could not have been more wrong, especially in a milking shed on a hot summer’s evening! In the event, it did not matter that we had been misled, but it pays to verify any information if you can.

Secondly, don’t come to New Zealand with unrealistic expectations. While many things will be very similar to the way they were in your home country, there will be many differences. If you have unrealistic expectations, you are bound to be disappointed and as we have seen, this can subtly poison your whole experience. Again, this book is intended to help you get a realistic picture of New Zealand and its people. These expectations may relate to the weather—there are wet, cold, miserable days in New Zealand; or to the social structure—you will not be able to have servants in New Zealand; or to the transport system—public transport is not frequent in New Zealand. Again, this book will give you the information you need to avoid having unrealistic expectations.

Thirdly, be prepared to be flexible and adaptable. There will be many instances where you would like things to be different, but they are not. New Zealanders are easy-going people; in fact, their casual approach to things can be quite a shock to those people who come from a more formal society. But it does mean that most of them are reasonable if they see you being reasonable. Be prepared to give and take, learn to laugh at your occasional mistakes, and you will lessen the culture shock considerably.

Fourthly, maintain contacts with your family in your home country and establish contacts with your cultural community here in New Zealand. If you don’t have any contacts with people from your home country here in New Zealand, this book will show you how to go about establishing some. People from your home country who have lived in New Zealand for some time can often be a great help. They have experienced culture shock and have developed ways of coping with it that will be appropriate to your culture.

So be prepared to encounter culture shock and be prepared to deal with it when it occurs. Hopefully this book will help you. It is designed as a culture shock absorber.