Chapter 4

Keep It Simple

Keeping it simple can relate to various aspects of your work, be it design, storytelling, or analysis. Before providing guidance on how you can meld simplicity into your work, let us define what we mean.

What Is Simplicity?

Simplicity for data visualization often focuses on minimizing the number of elements that do not add value to your display. These include borders, gridlines, axes lines, and boxes, which can easily distract from your core message. This recommendation also relates to the information itself. You should strive to create a visualization that focuses on specific aspects of the data, rather than including all fields and metrics but not saying much about any of them.

A broader definition describes simplicity as the state of being simple, uncomplicated, or uncompounded; freedom from pretense or guile; directness of expression.1

With data visualizations, you typically aim to communicate information, ideally in a way that makes it accessible quickly and easily for the audience. Sometimes, including additional visual indicators, such as icons or images, can enhance a design. However, if overused, they can distract from the core message.

This chapter focuses on different types of simplicity as they relate to data visualization, specifically:

- Simplicity in design

- Simplicity in analysis

- Simplicity in storytelling

Simplicity in Design

Simplicity in design can be recognized in visualizations that are clear, easy to understand, uncluttered, and impactful. Nonessential items are removed from these visualizations so that the data stands out, giving it space and removing distractions. Simplicity in design pays careful attention to the overall layout and positioning of individual components, the balance of charts and text elements, and the choice of colors, fonts, and icons, as well as the clarity with which all of these elements communicate to the audience.

The following sections provide examples and recommendations relating to these items to help you simplify your own designs.

Simplicity in Layout and Positioning

Whether you are visualizing data, designing dashboards, or telling data stories, there is a lot of flexibility when it comes to layout, sizing, and positioning. Most of these choices will, and should, be driven by the needs of the audience and stakeholders.

Devices Dictate Your Layout

In most organizations, the majority of information presented digitally will be consumed on laptops and desktop computers. When you create data visualizations for an audience using standard computer screens, size your dashboards accordingly and keep to a format that does not go beyond the dimensions of a typical laptop in your organization. Predetermine the size of your dashboard so you have full control over its layout and the positioning of different charts and text elements.

Most of the dashboards you design are likely to be in landscape format. Take care not to let them extend beyond the width of the screen because scrolling horizontally—as opposed to vertically—is not intuitive for most people.

Increasingly, dashboards are viewed on mobile devices such as phones and tablets. Interactivity through touch brings different design challenges. If your audience is likely to view visualizations on their mobile phones, you need to ensure that the number and size of the various charts, text boxes, and the white space around them suit the smaller screen size. The interactivity through touch, and the sizing of titles, subtitles, and annotations, as well as a vertical flow, also need to be taken into account for when users scroll. “Designing for Mobile” is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

Horizontal and Vertical Layouts

The flow of your visualization significantly influences your overall layout. Landscape format is suitable and most commonly used to show all of the information on a single page. This allows elements to be arranged easily and effectively, guiding the viewer’s eye across the page from left to right and top to bottom, a natural reading direction. A dashboard with a width-to-height ratio of 4 : 3 or 16 : 9 can fill up a screen nicely, maximizing the available space.

When we asked our community to visualize survey results of the characteristics people from different nationalities prefer in a romantic partner, Leonid Koyfman created a very straightforward dashboard in Excel (Figure 4.1), using a horizontal layout and strong, bold colors to show his findings.

Figure 4.1 Horizontal layout that fills the space nicely.

For a horizontal stacked bar chart like Figure 4.1, a landscape format works well, because it gives each bar enough space and allows the characteristics to be displayed in an easy-to-read fashion. If this bar chart were half the current width, the individual response categories would not be as easy to differentiate because they would be much closer together.

A portrait layout, where the height is larger than the width, is commonly used for a visualization that unfolds through a series of steps and charts. It typically starts with an introduction at the top and moves through key findings until reaching the conclusion at the bottom. Infographic-style dashboards and chronological flows can make for very compelling portrait layouts, following a Z-pattern from the top left to the bottom right of the page. While a horizontal timeline conveys the notion of time very well, it may not be the only chart you want to use in your overall visualization. The vertical layout can help you take your audience through the different stages of your visualization.

The visualization in Figure 4.2 from Athan Mavrantonis of air quality data from US-based measuring stations was created in a portrait format. Athan showed how ozone levels have changed over the years and within each year on a month-by-month basis, guiding the eye from top left to bottom right down the view.

Figure 4.2 Vertical layout that flows down the page.

The repetition of the US map for every month and year keeps this visualization simple and allows Athan’s audience to understand patterns as their eyes move down the page from one month to the next and across the page to see the changes over time.

Placing the color legend and definition of ozone at the top of the page helps the audience understand the key elements of the visualization up front. This is followed with small multiple maps that highlight the points in time at which ozone concentrations are most dangerous for our health. The visuals are followed by another two text elements: one focusing on answering the question “So what?” and the other providing practical tips for the readers who want to protect themselves from the harmful ozone. Athan’s layout choices frame the visualization with explanations and insights.

Using White Space

White space gives the charts and text elements of your visualization room to breathe, resulting in a cleaner look and feel. Think of it like effective pauses and silence in a speech. A well-planned pause can strengthen the argument someone just made. A pause can increase tension or apprehension. It can draw an audience in further, making them want to hear the rest of the story. Pauses set the scene for whatever comes next. White space, as the visual equivalent of a pause, helps your audience to focus on the next part of the story.

If your visualization contains a number of elements and pieces of information together, white space helps remove unnecessary distractions. Ideally, the charts are designed in a way that gives your audience clarity and lets them understand the key insights very quickly. Color choices, highlighting, annotations, and other ways of drawing attention to your findings help in the process. By leaving white or blank space around your charts, you are able to keep the focus of your audience on the key message rather than distracting or confusing them.

When the Makeover Monday community looked at life expectancy data by the World Health Organization, Colin Wojtowycz created a visualization that uses white space very effectively, as seen in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 White space helps provide focus on the important data.

Colin could have filled the white space in his visualization with text, filters, or additional charts. Instead, Colin chose to focus on a single country and visualized the significant drop in life expectancy during the genocide in 1994 in Rwanda. His design is impactful enough to make curious viewers do their own research to find the story behind the drop.

Intuitive Design

An intuitive design helps your audience understand quickly by being clear and easy to follow, and using familiar elements, such as colors and shapes. To assess whether your design is intuitive, ask yourself the following questions:

- Am I allowing my audience to read the visualization in a logical and natural order? Would those without any background knowledge or guidance follow this path? Does the visualization flow in a natural reading pattern from the top left to the bottom right?

- Do the colors logically fit the data? For example, should a solemn or serious topic be visualized using muted or dark colors? When representing female and male categories, do the colors form associations to gender?

- Are the titles, filters, legends, and controls placed in areas that make them easy to find without getting in the way?

- Does the design build trust with the audience? If the title is in the form of a question, is this question answered by the analysis and the conclusions? Alternatively, if the title is making a claim, does the data back it up?

Go through some of these questions as you design your next visualization to ensure what you create is straightforward and intuitive.

Reducing Charts and Text

It can be very tempting to create visualizations using as much of the available data as possible; it is tempting to choose a variety of charts to highlight different perspectives. A typical Makeover Monday visualization will have two or three charts, yet out of those there is a single chart that provides the insight really well, while the other charts are seemingly included to fill a gap. If the analysis can be told using a single chart, then that is what you should stick to. Any additional elements need a good reason for being there and should enhance, not distract from, the original insights.

This may mean that you may need to adjust the format of the final visualization and reduce it in size if a single chart does not take up as much space. Alternatively, consider using some of the available space to annotate the chart as a way of guiding the audience through the analysis. Keep in mind that these annotations should be succinct and add valuable information. As you read in the previous section, white space can be a useful and intentional choice in your design to present your analysis.

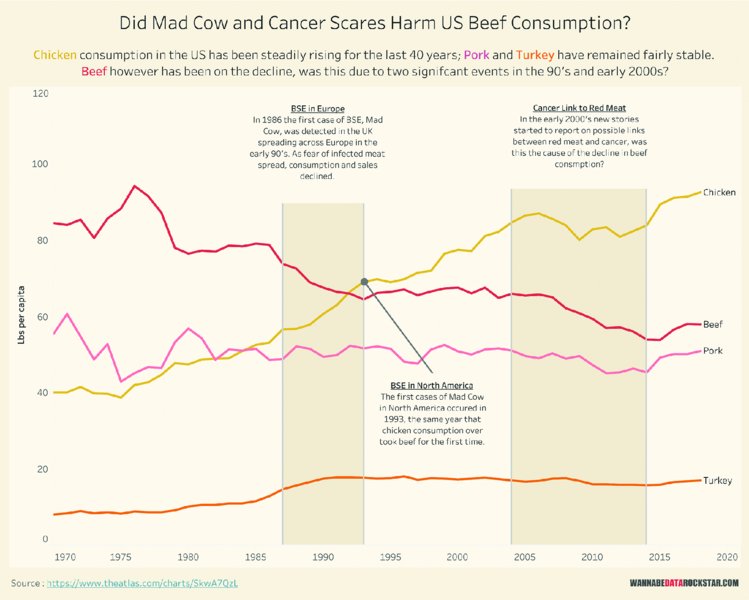

In Figure 4.4, Matt Francis used a single chart to visualize the changes in US meat consumption over the last few decades. Given that he created a single visualization instead of a collection of three or more charts on one page, Matt annotated the line chart and used reference bands to highlight his findings.

Figure 4.4 A single chart can be enough to reveal the analysis.

Adding annotations and reference bands helps clarify the possible reasons for a noticeable change in the pattern. In Matt’s visualization, two key points were worth calling out:

- The point in time when chicken consumption overtook that of beef

- The period of a significant decline in beef and pork consumption, coinciding with an increase in chicken consumption

Balancing Charts and Text

Simple and effective design means that you must carefully consider the right balance of charts, text objects (e.g., titles, subtitles, annotations, footnotes), and interactivity. There is no one rule that stipulates the perfect balance of visualization to text. Some visualizations are highly effective and use the minimum amount of text. On the other hand, a text-heavy infographic can still be informative, engaging, and impactful.

To achieve simplicity, ask yourself:

- Does a chart or text box make a topic, a statement, or an insight easier to understand?

- Would a particular chart benefit from a small number of annotations explaining specific data points?

- Can filters and controls be replaced by interactivity so that user selections in one chart update other areas of the visualization?

- Are color, size, or shape legends necessary or can you avoid them by explaining these elements in subtitles, descriptions, or the axis?

When you design data visualizations that will stand on their own, you need to provide a different level of information compared to visualizations that are presented by a person who can add commentary and descriptions.

For standalone visualizations where the audience is often unknown, the type of data and the topic it relates to will often influence the amount of detail you need to provide. Some topics and data sets are more complicated and may require additional explanations that can be best achieved through descriptions and annotations. Other topics are basic enough for a single bar chart with a well-chosen title to tell the entire story.

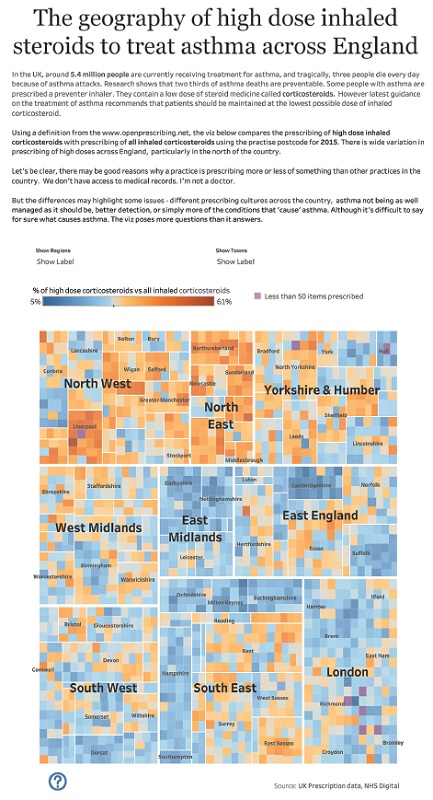

Figures 4.5 and 4.6 showcase these two different approaches, yet both visualizations are excellent examples of simplicity and effectiveness. Figure 4.5, by Rob Radburn, analyzes the geographical patterns of prescriptions for asthma medication in England.

Figure 4.5 Geographic treemap of high dosage inhaled steroids.

Figure 4.6 A well-chosen title and simple visualizations can tell an effective story.

Rob used a single visualization to showcase the geographical patterns in the data through a treemap that is aligned to the geographical regions of England. He included four paragraphs of descriptive text to highlight the risks surrounding high-dosage inhaled steroids.

When he analyzed data about the world as 100 people in Figure 4.6, Athan Mavrantonis focused on using colors, large numbers, only a few words, and two simple visualizations to put the data into a more meaningful context for his audience.

Simplicity in Colors and Icons

While the previous sections focused on overall simplicity and effectiveness for data visualizations, when it comes to colors and icons, there are three things that can make your visualizations anything but easy to understand:

- Too much color

- Too many colors

- Too many icons

Colors

Colors in data visualization play a big role in communicating your message. They can enhance your visualization significantly by drawing attention to certain aspects, to outliers or growth, to loss, to specific regions. However, too much color can distract and confuse. Using color sparingly will help your audience understand the key message. There are very few situations in which using many colors in a single visualization will work well. When you want your viewers to understand the significance of something, it is important to make that something stand out from the rest.

Icons and Images

By using images and icons in moderation, you can enhance your work and make certain topics appeal to an audience more easily. Images and icons can result in faster recognition and comprehension (e.g., using a flag for a country or a logo for a team). However, if you have many different icons and images in your visualization, you may leave your audience confused, because it can be difficult to differentiate between the objects and their purpose.

When you use icons and images, it is also important that these are easy to recognize. If you know your audience, you may be able to make assumptions about their familiarity with specific logos, flags, and commonly used symbols. If you do not know who your audience is, such as when publishing your work online, be conservative in your assumptions and use only icons that would be recognized and understood easily by everyone. Examples include:

- Symbols for women and men

- Traffic signs

- Small information icons, such as a lowercase “i”

- Signs with transport symbols such as planes, cars, or bicycles

Before you create a visualization with lots of icons and images, consider that their use can make your work difficult to understand. Not every data visualization needs to be thought of in a business context and not every topic needs to be presented in a formal and serious design. However, each visualization should represent your ability, as an analyst, to identify the key insights, build a story around them, and communicate it effectively.

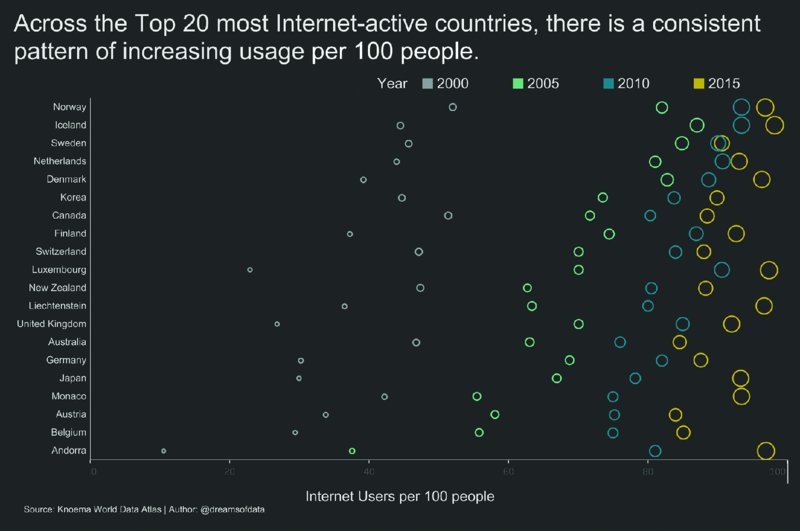

Keeping your visualization clean and uncluttered, adding color to highlight or draw attention, and using icons and images sparingly will make it easier for your audience to follow your visualization and gain insights from it. The straightforward visualization in Figure 4.7 by Alicia Bembenek uses color effectively and manages to tell a clear story without any icons or images.

Figure 4.7 Example of using color to highlight and removing unnecessary details.

Alicia created a dot plot to show the progression of internet usage by country over time. The pattern allows the audience to see quickly that all countries move in the same direction, with some reaching higher penetration of internet usage at an earlier stage than others.

Simplicity in Analysis

Every analyst has their own way of approaching an unknown data set. Some focus on the numbers first, while others go straight into building charts and graphs. Some analyze the metadata, while others want to focus on the data that is in each field. When you find yourself looking at unfamiliar data, you want to avoid feeling overwhelmed and instead feel excited to explore, to analyze, to ask questions, and to find answers that you can share with your audience.

Chapter 3, “Know and Understand the Data,” goes into detail around becoming familiar with your data set. The following section provides a number of suggestions to help you through your analysis. For new and less experienced analysts, these suggestions can be helpful to avoid getting lost among the noise in the data and instead help you find the story in the data.

Getting Started with New Data

Typically, when you approach a new data set you will know something about it and the purpose of the analysis. For example:

- What type of data is it? Is it survey data? Does it come from sensor measurements? Is it a set of summary statistics or detailed transaction-level records? There is an endless array of possibilities.

- What is the topic of the data? Are you looking at economic data from different countries around the world? Is it feedback results from a student survey or individual transactions of a payment system?

- Who is the audience? Are you creating analysis and visualizations for an unknown online audience or is your audience inside your organization?

- What tools do you have available for exploring and visualizing the data? Is the data clean and prepared for you or do you have to do further data preparation work to make it ready for analysis? Do you have visual analytics software to speed up your analysis process? Are you constrained to using tools that require you to wrangle numbers and limit the type of analysis you can do?

These questions are a set of the parameters within which you will undertake your analysis and they determine how far you can take the data. So how do you start your analysis of a new data set?

Start Simple

Different data sets allow for different types of analyses. Starting simple is a good way to approach a new topic and get a better understanding of the data. With a rich data set containing very granular data over a long period of time, you could work with predictions and forecasts. However, a better way to approach the analysis would be to start identifying trends over time. If you are new to data analysis and visualization—and even for those who are experienced—start from a high level and work your way into the detail.

For time-based data this could mean looking at the data across the years, drilling into quarters and months to see whether interesting trends and patterns emerge. Once you understand the summary level, you can work on defining some of the questions you want to explore further. For example:

- Are there specific dates that differ from the rest across all years? If you look at air traffic data, public holidays probably stand out because of increased flight traffic before, during, and after these days.

- Does a specific trend over a period of several years hold true across decades? Has the situation improved over time or did it get worse? When looking at environmental data like carbon emissions, you may notice lower levels many decades ago, followed by a strong increase and then a gradual decline as measures are put in place to reduce carbon emissions.

- Is there a specific time of the day that differs from the remaining hours? Are there one or two weekdays that stand out compared to rest of the week? Commuter data typically shows very specific patterns around time of day and day of the week and such patterns are worth exploring.

Visual analysis of data gives you the ability to ask and answer questions quickly. Along the way you will find more questions and hopefully more answers. As you work through the data set this way, make sure to save the different steps and perspectives, so that when the time comes for putting together your visualization, you can evaluate which charts or ideas are best to include.

Know When to Stop

What if you hit a dead end? What if you have a hunch and you spend significant time exploring the data and cannot get to the answer? Is it all a waste of time? Certainly not. These situations can be frustrating because you may get wedded to a particular idea and do not want to let it go and move on. However, moving on is exactly what you need to do.

If the story turns out not to be a real story and your hypotheses are not confirmed, it is okay to put your original ideas aside instead of backing up your hypothesis with weak arguments and data that does not stand up to real analytical scrutiny. Do not be afraid to acknowledge that there may not be any interesting insights in a particular data set.

Simplicity in Storytelling

How do you tell a story that is easy to understand? How do you tell a complex story in a way that is accessible for your audience? Moving beyond the design and analysis into the area of storytelling is another important aspect of the overall idea of keeping things simple. This section provides tips for finding insights and focusing on the key message.

Finding Insights

The first part of creating a story is to have something worth talking about. By following the analysis recommendations in the previous section, you will have a couple of angles that comprise the basis of your story. While analysis is about finding those interesting insights in a data set, storytelling is about bringing them into a form that you can communicate to your audience.

While it can take some time to find a story in a data set, you can easily create impactful visualizations from the first insights you come across. Sticking to basic and easy-to-understand insights while making enough time to practice regularly is perfectly fine. To help you find a story in your data, consider the following:

- What do you notice?

- Are there obvious outliers?

- Are there trends that are immediately apparent?

- Are there possible correlations between two metrics?

- Are there interesting clusters in your data?

- Are there repetitive patterns in the data, such as seasonal spikes or troughs?

Any one of these observations can be a story in itself. Naturally, you can combine the findings and bring them all together, but this bears the risk of having disparate stories that may be difficult to integrate. Instead, pick one story and stick to it, while completing it in a reasonable amount of time.

One of the very memorable challenges we gave the Makeover Monday community was data about the migration paths of two dozen turkey vultures in North and South America. Klaus Schulte found a story in the data of a single bird and turned it into the visualization in Figure 4.8.

Figure 4.8 Simplifying the data can help simplify the story.

Klaus’s focus on the data of turkey vulture Prado meant he could go deeper into a subset of the data and spend his time analyzing the migration patterns around the LA region where this nonmigratory bird moves during different times of the year.

A focus on simplicity in storytelling by choosing one specific topic in a larger data set is a good reminder that you do not have to use all the data all the time. Using a subset is fine and can make for an interesting analysis and visualization as a result.

Focusing on a Key Message

Highlighting your key message through the effective and minimal use of color and by creating a clean overall design can strengthen the impact it will have on your audience. If you focus on a single insight, make sure it stands out, make sure it is well supported by the data, make sure the analysis is sound, and then bring it all to life through thoughtful formatting and attention to all the small details that make a visualization exceptional.

In Figure 4.9, Joe Kristo visualized data about the highest-paid jobs in Australia and the difference in pay for men and women. He focused his analysis and resulting visualization on those jobs where women earn more than men.

Figure 4.9 Example of a clean, simple design with minimal colors.

The bar chart and the clean formatting help his audience to see the two jobs he highlights in red on the far-left side, where women are paid more than men. The remaining gray bars show the pay differential that favors men.

Summary

Keeping visualizations simple by practicing simplicity in analysis, design, and storytelling requires ongoing work; it is worth the effort because it will help you become more effective at communicating information. This chapter provided a number of suggestions to help you find a focus for your analysis and to turn it into a great visualization. Take some of them into your next data project and they will help you work more efficiently to get to your insights.

When it comes to simplicity, try removing some of the embellishments from your visualization in order to bring more clarity to your message. Less is certainly more when designing effective data visualizations and most topics benefit from a clean-looking layout that makes the data the focus of your analysis.