I don’t need the money, dear. I work for art.

—MARIA CALLAS

Famed soprano Maria Callas died at age fifty-five in 1977. She made the news when she transformed her rotund figure (she was once called “monstrously fat”) into that of a svelte and sexy Diva at the height of her career, even if music critics marked her weight loss as the downturn of her vocal brilliance. She was more interested in having fun and dated powerful men. She became a favorite of tabloid gossip when, while still married, she was seen with Aristotle Onassis, and the tabloids reveled in her anguish when he chose Jacqueline Kennedy over her. Rumors circulated that Maria kept her weight off by ingesting tapeworm larva, but she insisted it was a sensible diet and said, “I have been trying to fulfill my life as a woman.” In the end she lived isolated in Paris, unhappy in her quest for love, and acquired a taste for non-caloric Quaaludes, a sedative-like drug that gives a euphoric though rubbery-legged feeling. Officially, French officials deemed her death was due to “undisclosed causes,” though they cited a heart attack when pressed by the media. Others claimed she was murdered for her sizeable estate. A note written by Callas was found near her body, though it raised only more questions about her final state of mind. She borrowed a line from the suicide scene in the opera La Giocanda: “In these proud moments.”

You can tell a lot about a fellow’s character by his way of eating jellybeans.

—RONALD REAGAN

There’s something about Canada, some say the air, water, or maybe it’s the bird’s-eye view of the United States, that produces an inordinate share of successful comics. However, for John Candy it was the food there, across the border, and ultimately everywhere, that was both his success and ruin. As soon as he died, at age forty-three, tabloid newspapers ran headlines indicating that Candy ate himself to death, and offered to give details of his eating binges in full color, without mentioning his cigarette habit, workaholic ethics, and a genetic disposition to heart disease. The fact that he had ballooned to 375 pounds at the time of his death and was working twelve-hour days in stifling Mexican heat while shooting his last movie led to a massive heart attack: The autopsy found he had nearly complete clogging of the arteries. In reality, his true obsession was acting, either comic or dramatic, and like a writer who believed drinking would make his books better, Candy assumed his rotund size brought him roles. Given the public’s expectations, it might’ve been true for Candy, since from the beginning he gave his best performances playing the obese, love-able loser with low self-esteem. On screen he made jokes about his weight, but when the cameras stopped Candy was self-conscious to the point of self-loathing. He attempted a few times to lose weight, but couldn’t gamble that the next film that cast him as the big man would be the one that finally brought him to the level of stardom he sought. Ultimately, he never gave himself the chance to reinvent his image. Candy’s career was mixed, with hits often punctuated by a string of flops that made downtime impossible, and despite his growing size, he worked nearly nonstop, leaving a cinematography record of more than thirty-four films in fifteen years. That he killed himself solely by eating is not entirely true; it was only the means to a greater obsession that ended his life early, in 1994.

I think I may have become an actor to hide from myself. You can escape into a character.

—JOHN CANDY

Eating oneself to death is not an exclusively comedic act, and even took down a few of the ultra-serious. Julien Offray was a Fre nch philosopher and is credited with inve nting cognitive science (defined as the “study of mental tasks and the processes that enable them to be performed”). He also wrote of the joys of materialism for materialism’s sake, authoring the book Man a Machine. Presumably, he didn’t intend the title of his book as a metaphor, since he frequently tested his body to the limits. As his last act, Offray conducted an experiment to prove the harmless effects of occasional gluttony. The philosopher was quite lean and always presented a carefree attitude, believing that life was meant for savoring one’s favorite material pleasures as they arose. At a banquet given in his honor in 1751 he found the pâte aux truffes to be so delicious that he devoured tray after tray—until he collapsed to the floor. He died the next day after suffering a high fever and delirium at age forty-one.

It is strange that all great men should have some oddness, some little grain of folly mingled with whatever genius they possess.

—MOLIÈRE

Sharp as a two-pointed pencil, young Truman Capote taught himself to read and write before entering first grade. He claimed to have written his first novel by the age of nine, and practiced at writing as diligently as others learned a musical instrument. His earliest years were spent in rural Alabama, where he was best friends with Harper Lee (author of To Kill a Mocking bird), but was moved to New York City before his teen years. There, his remarried mother sent him to a military school for a while to toughen him up in the hope of making him more masculine. Truman, however, was the type that seemed to his mother genetically born gay, a fact she took so seriously that she aborted two following pregnancies, afraid of giving birth to another child with his personality. When Truman finished high school he was steadfastly determined to become a writer, and thought college only a waste of time. He got a job at the New Yorker cataloging cartoons, but soon made a name winning prizes and publishing short stories in other prestigious magazines. By the time he was twenty-four, his semi-autobiographical novel Other Voices, Other Rooms had made the New York Times bestseller list. As much as Capote was dedicated to perfecting his writing style, he equally obsessed with his image (in contrast to former childhood friend Harper Lee), and set out to create a public personality for himself from the start. His sexual preferences, at a time when being gay was not openly accepted, his small stature that reached an adult height of five feet four inches, and a unique, oddly inflected and high-pitched voice, would have seemed to most a detriment. Yet he capitalized on his strangeness, and considerable intellect, to make inroads and became, at least outwardly, accepted into the company of high society. Capote’s publishing success grew astronomically after the publication of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, followed by In Cold Blood, so that few could argue with his artistic genius. Noted critic John Hersey praised In Cold Blood as “a remarkable book,” and writer Norman Mailer declared Capote to be “the most perfect writer of my generation.”

No one will ever know what writing In Cold Blood took out of me. It scraped me right down to the marrow of my bones. It nearly killed me. I think, in a way, it did kill me.

—TRUMAN CAPOTE

During the mid-sixties, he reached his heyday and considered himself the cat’s meow of the jet set when his ultra-exclusive “Black and White Ball” became a coveted invitation. He succeeded in fulfilling his obsession to be counted among the elite, though he began to realize that he was never truly considered their equal, and perhaps no more than an amusement. The notion that he was the modern-day John Merrick, “The Elephant Man,” an outsider allowed to mingle as a curiosity among the upper crust, took its toll. He drank more and more heavily and took drugs, entering numerous rehab programs while deciding to seek revenge.

Capote promised to write a book that would expose the secret foibles of the debutantes and dignitaries in his characteristic cuttingly crafted way. After many false promises and multiple delays in the delivery of his awaited tome, he became more and more ostracized, eventually withdrawing nearly entirely from the limelight. After a few drunken appearances on TV and more rehab, doctors determined that Capote’s brain mass was shrinking. He could no longer write coherently. In 1980, at age fifty-nine, he died during a morning nap, officially, from liver disease complicated by “multiple drug intoxication.” It seemed he had finally kicked his drinking habit, though barbiturates, Valium, antiseizure drugs, and painkillers were found in his blood.

Deborah Davis, in Party of the Century wrote: “The Black and White Ball was a work of performance art. It was a work that was every bit as important to Truman Capote as everything that he wrote,” although then young actress Candice Bergen, seen wearing a fluffy, long-eared mink bunny mask to the masquerade ball, called the whole deal “boring.”

When God hands you a gift, he also hands you a whip; and the whip is intended for self-flagellation solely.

—TRUMAN CAPOTE

Max Cantor was a Harvard-educated journalist who wrote in-depth articles about drug addiction for the Village Voice. While doing research about drugs and the addict population in the East Village, he too became hooked. He died from a hot shot in 1991, at age thirty-two.

Charles Dodgson, the author behind the pen name Lewis Carroll and creator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, had a peculiar fascination with eleven-year-old girls. Today, just a hint of this might get the sirens and red lights of cop cars swarming, but back then it didn’t seem to ruffle many feathers and Dodgson was allowed to keep his day job as an ordained minister and teacher. His hobby of photography and his portfolio of young girls, many of them nude, were explained by Dodgson as a noble rather than erotic pastime. He was merely interested, he claimed, in capturing the “ultimate expression of innocence.” Even though he asked the parents of an eleven-year-old girl for permission to marry when he was thirty-one (they declined), there is no evidence he acted out his desires. To his credit, Dodgson had a tremendous imagination and created original and memorable stories, featuring talking rabbits, grinning Cheshire cats, mad hatters, and a girl-heroine immersed in a world where everyone was crazy. The settings appealed to children, although they seemed to follow the landscape and logic of any good opium-induced dream. Dodgson was no stranger to opiates and laudanum, or to cannabis or hallucinogenic mushrooms.

The creative habit is like a drug. The particular obsession changes, but the excitement, the thrill of your creation lasts.

—HENRY MOORE

Records indicate Dodgson took laudanum to relieve migraines; some believe it was to ease his lifelong stammer. Dodgson was a gentleman of the haughtiest variety, and preferred not to mingle with the “commercial” classes. Sexually, he seemed to have relations with adult women, even though he wrote: “I am fond of children, except boys.” What caused his original genius to dissipate, and left him, in the end, publishing books that were barely readable and reeked of confusion, has the many prevailing academic camps divided into diverging theories. Some say his unrequited pedophilia, drug addiction, or lead poisoning was the cause of his demise. Others insist his habits were merely misinterpreted by Victorian Era standards. His genius lies in that he created work so unique it still needs to be debated regarding the source of his inspiration. Nevertheless, he died in 1898 at age sixty-five, officially of influenza and bronchitis, and of course, he never married.

A revival of Carroll’s popularity in the 1960s was due primarily to the suspicion of his insider knowledge of psychedelics, and was further established with the rock song, “White Rabbit.” Grace Slick and the Jefferson Airplane’s rock classic brings out the story’s thinly-veiled drug references.

One day Alice came to a fork in the road and saw a Cheshire cat in a tree. Which road do I take? she asked. Where do you want to go? was his response. I don’t know, Alice answered. Then, said the cat, it doesn’t matter.

—LEWIS CARROLL

Dodgson followed the protocol of the upper class and in his day no proper gentleman would be seen in a bar, buying liquor, or heaven forbid, have it smelled on his breath. Drinking was for the blue-collar chaps. An 1881 article in Catholic World noted that a gentleman “procures his supply of morphia and has it in pocket ready for instantaneous use. It is odorless and colorless and occupies little space.” For life’s daily aches and pains it was considered an appropriate choice. However, when Dodgson fell seriously ill at the end of his life— seemingly the effect of a lifelong use of opiates— morphine was withheld. Devout Victorian Christians believed the drug prevented “the good death of fortitude in the face of suffering.”

Success is having to worry about every damn thing in the world, except money.

—JOHNNY CASH

“The Man in Black,” Johnny Cash—by selling fifty million albums over a fifty-year career—became the most recognizable country singer in American music. He nearly died during his rise to stardom due to a serious addiction that lasted from 1958 to 1967, hooked as he was on amphetamines and alcohol. Although drug-free for some time, Cash later admitted he was addicted to painkillers, blaming it on an injury caused by his pet ostrich, which kicked him in the chest. Cash died in 2003 of respiratory failure due to diabetes, at age seventy-one.

If confusion is the first step to knowledge, I must be a genius.

—LARRY LEISSNER

Even though he never published a single book in his lifetime, this wiry, motor-mouthed hustler possessed a magnetic personality and became the electric spark that ignited an entire American literary movement. Raised by an alcoholic father in Denver’s transient hotel district, young Neal Cassady learned early to navigate fall-down drunks and hookers gathered in doorways. His education continued in reform schools, where he was sent for hot-wiring one too many cars. He met the founders of the Beat Generation, Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, while visiting a friend at Columbia University, and soon started a homosexual relationship with Ginsberg that lasted more than twenty years. Cassady’s most renowned contribution to literature was his friendship with Kerouac, to whom he was bound by their common interest in sports, which began in earnest when together they headed across the country. They traveled vagabond-style, out to discover themselves, searching for “lost inheritance, for fathers, for family, for home, even for America.” Cassady became the semifictional protagonist Dean Moriarty in the first well-received “stream of consciousness” novel, On the Road. Neal’s letters to Jack, with his run-ons, his jumping from one thought to the next, and his way of interrupting life, inspired Kerouac to write as Neal spoke. His influence wasn’t limited to Ginsberg and Kerouac; chronicles of his unique personality appeared in the writings of Tom Wolfe, Ken Kesey, Hunter S. Thompson, Charles Bukowski, and Robert Stone, and in the songs of Bob Dylan, to name a few.

Some believed Cassady, rather than being creative, suffered from a type of Ganser syndrome. Also called “prison psychosis,” the disorder describes a person who overstates his mood and feelings and mimics behavior observed in mental patients. It seemed the only explanation for Cassady’s “letting go,” known as he was for saying and acting out whatever he felt on the spur of the moment.

Cassady was well read, a fountain of information, citing observations and tidbits, everything from why the Chinese ate tadpoles as contraceptives, to how to change a spark plug. He never ceased to amaze his cronies or be the life of the party. Privately, Cassady was torn by Catholic guilt, often consumed with the notion that he was a sinner doomed to limbo. He ultimately thought his life was a waste.

He married often and had many children, and used whatever drug or drink was at hand. Cassady wasn’t a traditional alcoholic or heroin addict, but rather a “garbage head,” since he didn’t care what type of drug he took, as long as it would have an effect. He took anything that silenced the “you’re just a worthless piece of …” voice that plagued his brain. He wanted to be something, at first a football star, and then a writer, but saw himself as an ex-con and ultimately as the same book as his alkie father, only with a different cover.

Suffice to say I just eat every twelve hours, sleep every twenty hours, masturbate every eight hours, and otherwise just sit on the train and stare ahead without a thought.

—NEAL CASSADY

Toward the end, according to Carolyn Cassady, an ex-wife, Neal admitted that twenty years of fast living hadn’t left much. Before he went on the last of his many spontaneous road trips to Mexico, he was physically worn out, his mind not as fluid as before. However, he pulled his nineteen-year-old son aside before his departure and gave him the only inheritance he had to offer, telling him simply, “Don’t do what I have done.”

I became the unnatural son of a few score of beaten men.

—NEAL CASSADY

In 1968, four days before his forty-third birthday, Cassady was seen attending a Mexican wedding reception where he got high on barbiturates and some champagne. When the lanterns went dim and the mariachi band packed up, he decided to walk, alone, fifteen miles back to the next town via a deserted railroad track. He wore only a T-shirt and jeans and wasn’t prepared for the chill that descended on that starry night in March, coyotes howling in the distance. He laid down for a quick snooze, it’s presumed, and died. The physician who performed the examination on his corpse cited the cause as “general congestion in all systems,” and not as a result of living the experiences of ten lifetimes in the space of one.

The title of foremost wild man of the Beats belonged to Bill Cannastra. Like Cassady, he was a non-artist who influenced a generation of writers and painters and set the bar for outrageous behavior, free sex and abandon, and drug use more than a decade before it became fashionable. The parties at his apartment on West 20th Street in Manhattan in the late 1940s became legendary. He was a graduate of Harvard Law School but to the law he preferred spectacle, drama, and nihilism to the extreme, holding free-for-alls where anything went, including orgies with both sexes. He is often credited with giving Jack Kerouac the idea of using a roll of uncut paper as the best means to transcribe in one sitting the breathless novel the young writer was talking about. Cannastra died when he stuck his head out of a moving subway near Astor Place in New York City in the spring of 1950, at age twenty-one. He was drunk and high and thought it cool to wave goodbye to his friends. What they witnessed instead was his head rolling on the tracks as the train went on down the tunnel, his eyes wide open, staring into space with disbelief. Afterward, Cannastra’s former lover Joan Haverty was so distraught over his death that she accepted a spur-of-the-moment proposal from Jack Kerouac and married him two weeks later.

I was an altar boy, but then at the age of fourteen I discovered masturbation and all that went out the window.

—GUILLERMO DEL TORO

Gaius Valerius Catullus was a first-century Roman poet who died before he was thirty. He came from the upper class and hobnobbed with the elite. While still a teenager, he wrote a satirical poem about Julius Caesar when the future emperor was only a governor, and nearly got his head handed to him, but was spared by the intervention of Catullus’s well-connected father. After that, he wisely favored the less risky love poem, and even more so when he became obsessed with a classy woman ten years older than he who thought Catullus unsuitable. The erotic poems he wrote were so explicit, even the Romans called them obscene. He never gained scholarly notoriety in his life though fellow poets in his time and afterward admired his craft and imitated his techniques. He was praised for his genius in injecting personality into poetry, and for his stylistic techniques that incorporated his unique personal voice. According to many scholars, Catullus held the most influence on Horace when he wrote his famous Odes. Many of the particulars of Catullus’s life are unsubstantiated by second-hand accounts, though it seems his work had an underground popularity; and before the days of X-rated magazines, his more sexual poems found their way to become favored bathroom reading. The many ragged-edged copies unearthed by archaeologists suggest that his more explicit verse made a good aphrodisiac for masturbation. It’s uncertain if Catullus ever married or even had a girlfriend, though his official cause of death at a young age in 54 BC was “exhaustion.” Perhaps his obsessive preoccupation with a certain type of self-indulgence was greater than many historians wish to admit.

The Romans already had the word masturbor in the language to describe Catullus, and its meaning survived changing lexicons until a seventeenth-century dictionary defined “mastuprate” as “dishonestly to touch one’s privates.” John Cowper Powys, a novelist, and direct descendant of the great English poet John Donne, claimed openly that masturbation was his inspiration and obsession, since he loathed penetration, unless, of course, for an enema. It worked for him, and he died in his nineties in 1963 with perfect vision. The Kinsey Institute study on sexual behavior of fifty years ago claimed that 92 percent of the male population practiced the art, while only 62 percent of females engaged, with new researchers suggesting that for males it prevents prostate cancer. The modern dangers stem from addiction to Internet pornography, with more than 1.8 million people each hour of the day glued to the monitor watching porn, and doing what comes naturally, with no need to read between the lines of Catullus’s poetry for erotica.

Sex. In America an obsession. In other parts of the world a fact.

—MARLENE DIETRICH

Every forty minutes a brand-new porn video is released. In the nineties, porn stars dropped by the dozens from AIDS, a fact made public when Brooke Ashley tested HIV-positive after breaking the anal intercourse record, with fifty men. More safeguards have been established since. However, murder, suicide, and overdose permeate the doings of artists occupied expressing their talent in this medium. A few include: Trinity Loren (thirty-three) and Linda Wong (thirty-six) died from overdoses, as did J. D. Ram (twenty-six) and Jill Munro (twenty-five) on heroin, soon after appearing in Consenting Adults. Lolo Ferrari billed as “the woman with the largest breasts in the world,” at seventy-one inches via silicone, broke a Guinness World Records for another obsession, undergoing twenty-two breast-enhancement procedures. It was believed her death, at thirty-eight in 2000, was from a rupture, though according to her husband, Lolo picked out a white coffin and laid out a pink dress for her wake three days before he claimed she died of an overdose. When it was discovered that a nonlethal dose of medication was in Lolo’s bloodstream, her husband said she instead died in her sleep, suffocating on her breasts. Lolo had planned an operation to reduce her stupendous size to an expression more manageable, such that suspicions of foul play surround her death.

I never wanted to be famous. I only wanted to be great.

—RAY CHARLES

The famous and (to many) great musician Ray Charles, despite being totally blind by seven, taught himself to play the piano. With both parents dead, he was left alone in his teens, but Charles was already good enough to make a living playing piano with any number of bands. Long before he had his hit “Georgia On My Mind” or was invited by President Jimmy Carter to the White House, Charles survived a seventeen-year heroin addiction. He died of liver failure at age seventy-four in 2004.

I marvel at the resilience of the Jewish people. Their best characteristic is their desire to remember. No other people has such an obsession with memory.

—ELIE WIESEL

Paul Celan is considered one of the best of the post–World War II German poets, and gave a voice to a painful duality, including guilt and rage, that many surviving German Jews experienced. Although he believed the Nazis stole his heritage and diluted the German language with propaganda, he felt it was his calling to use words to revitalize the long-respected tradition of Deutsch literature. He coined new words and used archaic references that made accurate translation difficult. Even though Celan garnered the respect of his literary peers and won international awards, he was often criticized by the public, which was put off by his curt, enigmatic lyrics. After one reading, Celan said, “this cold city Paris—It’s gone quiet around me.” When the widow of German poet Yvan Goll accused Celan of plagiarizing much of her late husband’s work, Celan cracked. He was incapable of handling another round of persecution, and in April 1970, at age forty-nine, he jumped into the Seine River. His body was found downstream three weeks later, caught up in the nets of a French fisherman.

The trauma of persecution was no figment of Celan’s imagination, even if the accusation of plagiarism seemed hardly enough to make Celan call it quits. He witnessed the Nazis’ murder on a mega scale, and himself survived two years in a labor camp. In addition to Jews, Gypsies, Russians of Asiatic descent, Jehovah’s Witnesses, male homosexuals, anyone with a disability, those previously convicted of a crime, as well as artists and writers not in line with regime ideas—more than eleven million were exterminated. Celan’s mother was shot when unable to continue work at a labor camp, and his father perished of typhus in German custody. Other ghosts, which Celan tried to exorcise with poetry, led him to the river and an early death.

Only in one’s mother tongue can one express one’s own truth.In a foreign language, the poet lies.

—PAUL CELAN

For some, the blast of genius has a short lifespan. Once this period of hyperactive creativity begins, one’s physical age becomes irrelevant and follows the ticking of another clock, many times ending in its own implosion soon after it began. Thomas Chatterton exemplified this phenomenon like few others, and is now considered the first Romantic poet of the English language. His was a burst of ingenious brilliance during puberty when, at age twelve, he became obsessed with achieving literary greatness. He came from a poor family in the overcrowded town of Bristol, England. His widowed mother arranged to send Thomas to a private school but he was dismissed, considered an idiot and too scatterbrained to learn. At age eight he was sent to a charity school that was set up for the less bright to become business apprentices, being taught only the barest of remedial skills. Here he had his head shaved, was made to wear an ankle-length smock, and was treated invariably as no more than an indentured servant. However, when he went back home during holidays from school, his mother gave him the few pennies he needed to borrow books from the library to satisfy his unusual thirst for knowledge. Thomas’s favorite place to study was a nearby graveyard, crotched behind lopsided tombstones etched with skeleton heads and angels. When he was twelve, Thomas found a stash of old, blank parchments sequestered in a forgotten trunk in his attic, which his deceased father had once removed from the family’s parish church. Stealthily, he took these faded parchments to a lumber room and, with pieces of charcoal and lead powder, wrote original poems that looked authentically like the work of some ancient, medieval writer. He saw the marketing potential of this immediately, and guessed correctly that if he presented his poems as anything other than a “discovered” medieval classic, he would be patted on the head and dismissed as a lower-class urchin grasping beyond his capabilities. He showed one of his parchment poems to an official at the school and duped him immediately into believing it was indeed an ancient find. The favorable reaction was so great that Thomas went on to create an entire body of work by a made-up monk he called Sir Thomas Rowley.

Youth is not a question of years: one is young or old from birth.

—NATALIE CLIFFORD BARNEY

Thomas’s station in life at school, and later when at age fifteen he was apprenticed to a Bristol lawyer, irked him, forced as he was to sleep with the footboys, being spied upon to make sure he wasn’t idling away a moment of time. Thomas was frequently insulted and belittled, and if he was caught writing a poem the head of the house ripped it up, kicked him in the ass, and sent him to scrub a bedpan. Meanwhile, in his secret life as Sir Rowley he saw his poems put in print, published in respectable magazines, and purchased by a notable scholar who included his medieval pieces as examples of the work of a late honorable citizen of Bristol. When Thomas came forth and revealed he was the true author, he was scoffed at, believed incapable of creating such masterpieces, and ridiculed as a liar. Thomas grew morose, and devised a plan to be relieved of his apprenticeship obligation by saying that he intended to commit suicide in his master’s house. He was promptly deposited to the curb, dismissed with not a cent to his name.

I must either live a Slave, a Servant; to have no Will of my own, no Sentiments of my own which I may freely declare as such; —or DIE—perplexing alternative.

—THOMAS CHATTERTON

In April 1790, when Thomas was seventeen, his friends donated money for his transportation to London, where he quickly got hired as a freelancer for numerous magazines. For a time he subsisted on the paltry payments for his writings, though when summer approached, back when businesses in the big city traditionally closed down, work dried up, which suddenly left Thomas in dire financial straits. He continued to write cheerful letters to his mother, extolling his rapid rise in the ranks of writers, while in reality he was holed up in a rundown boarding room without a crumb to eat. It’s reported that many tried to offer help, and that his landlady, named Mrs. Angel, brought him food, which he refused, insisting that he was fine and needed charity from no one. At the end of August, on one exceptionally hot evening, three months shy of his eighteenth birthday, Thomas Chatterton drank a cup of arsenic tea. He was found in his room the next morning amid a shredded heap of his torn-up manuscripts. His death was deemed a suicide due to reasons of insanity.

Arsenic was discovered as a perfect poison in AD 700 by an Arab alchemist, and long had a reputation for causing certain death. In England, a pile of the poisonous white powder was spooned at every doorway to kill rats. It was mostly used for murder, and was rarely the choice for a creative suicide. Chatterton was the first of note, though George Periolat, a silent film star, also took his tea with it in 1940. Francesco I de’ Medici and his wife, patrons of the arts, were fed it secretly, both dying in 1587. Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne fell ill from it, since it was used to make green paint greener, and Claude Monet went blind, smeared as he was in all the colors, many of which contained arsenic.

Color is my day-long obsession, joy, and torment. To such an extent indeed that one day, finding myself at the deathbed of a woman who had been and still was very dear to me, I caught myself in the act of focusing on her temples and automatically analyzing the succession of appropriately graded colors which death was imposing on her motionless face.

—CLAUDE MONET

I put all my genius into my life; I put only my talent into my works.

—OSCAR WILDE

Geniuses have been known to work nonstop, experiencing a sense of timelessness during especially enlightened periods of inspiration. But when that pace is extended and becomes a norm, certain frenzied work habits are as deadly and as addictive as drugs. Famed Russian author and playwright Anton Chekhov, in addition to being a literary genius, would now be called a workaholic, which seems to be the underlying cause of his early death. As a medical doctor, he traveled from Siberia to Moscow tending to the poor and wealthy alike at a grueling pace, filling every other spare moment he could find by writing. When he finally stopped practicing medicine to do nothing else but write, Chekhov continued at a demanding self-imposed work schedule, which led to repeated bouts of exhaustion. When he coughed up his first glob of blood, at age thirty-seven, knowing it was the onset of tuberculosis, the most elusive of Russian literary bachelors decided to get married. Previously, Chekhov preferred the more time-effective romance found at brothels. However, the woman he married had to agree not to consume too much of his writing time—she remained in the city and he in the country. As Chekhov said, “Give me a wife who, like the moon, won’t appear in my sky every day.” But in reality, medicine in his early years took up most of his hours, more than any wife, though literature remained his true mistress. His ability to convey social ills and empathy for human plights through an ease of ordinary conversation-like dialogue was his genius. The superb craft of his short stories is still admired by writers. Novelist and short story writer Eudora Welty once said, “Reading Chekhov was just like the angels singing to me.” Vladimir Nabokov called Chekhov’s story “Lady with a Lapdog” “one of the greatest stories ever written.” Chekhov produced hundreds of short stories, novels, nonfiction books, and nine plays that are still regularly performed around the world and remain his most popular legacy. Chekhov finally slowed down only on his deathbed, at age forty-four in 1904. The physician in attendance gave Chekhov a shot of camphor (a chemical used in embalming) and handed him a glass of champagne until he closed his eyes in peace. His body was then placed in a railroad car and kept fresh by being placed on top of bushel baskets filled with fresh oysters packed in ice. Once his body reached Moscow the loss of his brilliance was commemorated with a lavish funeral.

Doctors are just the same as lawyers; the only difference is that lawyers merely rob you, whereas doctors rob you and kill you too.

—ANTON CHEKHOV

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle of Sherlock Holmes fame, and poet William Carlos Williams were doctor-writers who apparently used their medical knowledge on themselves and lived long. François Rabelais, a French doctor, was called a Renaissance man back then because he also wrote humorous satires and used references to the more grotesque parts of human anatomy when poking fun at political figures or church customs. He also wrote novels that had party-loving heroes telling dirty jokes. When Rabelais died, in 1553 at age fifty-nine, neither career path had paid off. Wishing to be remembered as a humanist, he penned the best will ever: “I have nothing, I owe a great deal, and the rest I leave to the poor.” Years later, French writer Honoré de Balzac said Rabelais was “a sober man who drank nothing but water,” despite the robust characters Rabelais created. When this doctor-writer got sick, he trusted none of the treatments he prescribed for others and instead drank gallons of water to flush out his system. His death seems more from what is now called “water intoxication,” a condition that kills from drastic potassium and electrolyte imbalance.

Towering genius disdains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored.

—ABRAHAM LINCOLN

Sir Winston Churchill was the British prime minister during World War II, and was credited as the stalwart leader who prevented Nazi Germany’s invasion of England. He also won a Nobel Prize in Literature, for his historical writing, in 1953. Churchill made no excuses for his love of drink, saying he acquired the habit out of necessity: “The water was not fit to drink. To make it palatable, we had to add whiskey. By diligent effort, I learned to like it.” Showed reports on the ill effects of excessive drinking, he noted: “Statistics are like a drunk with a lamppost—used more for support than illumination.” Despite his brilliance, Churchill never seemed to correlate his numerous strokes or what he called “his black dog of depression” to alcohol. A miracle of sheer perseverance, Churchill lived to the age of ninety, dying in 1965 from a blood clot.

You may have genius. The contrary is, of course, probable.

—OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES

If ever there were need for a poster-boy for persons born with a sensitive soul, actor Montgomery Clift could fit the bill. He was a twin, though apparently even at birth was reluctant to enter the world, arriving several hours after his sister. His father was a low-key investment banker while his mother was reportedly the passive-aggressive, domineering type that had Montgomery on stage by age thirteen and cast in a Broadway play two years later. He was an extremely handsome child, calm and, from the first, a natural, possessing the uncanny ability to act before an audience as if none were there—performing, it seemed, only on the private stage inside his head. By age twenty he was a theatrical sensation, deluged with scripts, and was known to have numerous offstage affairs with actresses and actors. Although he was open about his attraction to both sexes, a fact eventually accepted by his parents and friends, publicists kept a tight lid, knowing that in the 1940s, his bisexuality would’ve been the death knell for his promising career. Within two years of going Hollywood, Clift became a national heartthrob, the sensitive, disillusioned hero of postwar America, earning his first Academy Award nomination in 1948. Clift said he had no burning passion to act and took his time picking and choosing from the many scripts offered. Yet he made film after film, some say, as he believed his mother would want him to do. Beginning with his performance in From Here to Eternity, which many consider Clift’s finest, he began to drink on movie sets. Regardless of the accolades, Clift seemed resolved from then on to commit suicide the slow way, and was seldom seen sober. Movie studios took out a life insurance policy on him, the industry’s own “death pool,” of sorts. In 1956 they almost collected when Clift drove drunk and crashed into a pole while costarring with Elizabeth Taylor in Raintree County. His face was irreparably mangled and his once classic good looks were instantly gone, the left side of his face paralyzed, his mouth drooping and nose askew despite plastic surgery attempts. There were no more close-ups. Clift persisted and rallied, trying to regain the good reviews he once took for granted.

Failure and its accompanying misery is for the artist his most vital source of creative energy.

—MONTGOMERY CLIFT

By 1962, while shooting his last major film, Freud, Clift’s reputation took a permanent nose dive. He had difficulties with director John Huston and couldn’t remember his lines, in addition to suffering from blurred vision. His soft-spoken personality had become belligerent and argumentative. When Clift’s delays made the studio lose money they filed a lawsuit against him. Clift was unemployable and branded a troublemaker: He retreated from the public eye, becoming a virtual recluse in his New York City brownstone. Although he was reportedly rendered impotent by drug and alcohol abuse, technically no longer bisexual or otherwise, he was attended to by a faithful male companion. In 1966, at age forty-five, he was discovered dead, lying naked in his bed.

A man loses his sense of direction after four drinks; a woman loses hers after four kisses.

—H. L. MENCKEN

Marilyn Monroe starred with Clift in The Misfits, a fitting title for both stars, and was considered for the role as the neurotic patient in Freud, although Monroe chose a film with a more prophetic title, Something’s Got to Give. Like Clift, Monroe ended with a bitter view of Hollywood; for her, it was because she had been stereotyped as a “dumb blonde.” Although both Monroe and Clift played lost souls in The Misfits, she had no time to deal with Monty’s drug and alcohol problems, suffering her own nervous breakdown and being extremely stressed by the Nevada heat during production. Monroe likewise relied on alcohol and drugs, but added affairs with high-powered politicians to the mix. She was found dead under still mysterious circumstances, though her death (in 1962 at age thirty-six) was officially ruled an overdose. According to Joe DiMaggio, a former husband, Marilyn was planning on remarrying him when she died, and that her true fatal obsession was a search for love.

No man’s genius, however shining, can raise him from obscurity, unless he has industry, opportunity, and also a patron to recommend him.

—PLINY THE YOUNGER

Though he became a military genius and for better or worse was instrumental in securing India for Britain, Robert Clive had a tough time in school. Master Robbie was not interested in the basics of reading and writing, though he had a knack for arithmetic, especially when it came to counting money. He bounced around from school to school, missing out on requirements to attend more prestigious universities. Schoolmasters believed he had some sort of depressive illness, but that was the diagnosis back then for anyone who couldn’t seem to follow the rules. He was what they called a hooligan, certain to find his way to a premature jig at the end of a noose. Robert started out by climbing up cathedrals and hiding behind gargoyles to scare old ladies, and he progressed to running a gang to extort money from shopkeepers. Although he came from royal stock, his family’s estate was a poor one, so when Robert was eighteen, in 1744, his father believed the best way to get him out of town was to secure him a job with the East India Company as a bookkeeper aboard a ship bound for India. Then, India was a wild place, ruled by various warlords who made trade risky, with the French, Dutch, and Portuguese vying to get a piece of the pie. Clive had no military training, but when dangerous conflicts and skirmishes arose he was singled out for his crazy brand of bravery. Eventually, he was convinced to leave his civil ser vice position with the trading company and join the British army.

When Clive first landed in India, he was penniless and distraught. He secured a pistol, put the barrel to his head, closed his eyes, and pulled the trigger. When nothing happened he clicked the trigger a few more times, until he threw the gun down in disgust. He then said: “It appears I am destined for something—I will live.” Clive’s giant pet tortoise, Adwayita, which he was given as a gift while in India, fared better. The creature died in 2006 of a cracked shell at 250 years old.

Clive proved to be a natural leader and wasn’t afraid to dupe warlords into signing treaties, to pit one against the other, or to use any tactic to ensure victory. In short, he applied the same extortion tactics he used on the shopkeepers back in London. In a battle for Bengal he routed fifty thousand of the enemy with only three thousand men, and said that he saw in a dream that he could win. He didn’t tell anyone that his confidence lay in a deal he made with the defending force’s field commanders, who assured Clive that many of the enemy would desert their ranks. His bold approach rattled opponents, and Clive was quick to levy crushing fines and force enemies to pay steep tributes. Through his shrewd negotiations and military genius, the whole of India became part of the British Empire. Prestige, wealth, and greater titles than his father ever had greeted him on his visits to London. When summoned to a hearing at Parliament that questioned the source of his wealth, Clive was insulted and replied: “By God! I stand astonished at my own moderation.” Eventually, it seemed the visions or dreams he often used to justify tactics were discovered to come from a source other than a sticky night on a cot. While in India, Clive picked up a taste for opium, and it appears his addiction lasted many years. At age forty-nine, in 1774, Clive took one last hit of opium and, for reasons no one knows, then stabbed himself in the neck with a pen knife. Suicide was a serious stigma and Clive was placed in an unmarked grave, which remains so to this day.

Before India was part of the British Empire, most opium came from Turkey, but Clive discovered that poppy plants grew in Calcutta, and although it had a slightly different taste, Indian opium was no less potent. It was readily available and was smoked by the native population in long pipes. It wasn’t until 1832 before a doctor who traveled with Clive convinced the British government to allow Indian opium to be cultivated on a large scale. A New York Times article from 1896 described an Indian government-sanctioned opium den: “Men and women lying on the floor like pigs in a sty. A young girl fans the fire, lights the opium pipe, and holds it to the mouth of the last comer till his head falls heavily on the body of the inert man or woman who happens to lie near him. In no groggery, in no lunatic or idiot asylum, will one see such utter, helpless depravity as appears in the countenances of those in the preliminary stages of opium drunkenness.” Today, Punjab, a northern state in India, has the highest population of opium users in the world.

Since when was genius found respectable?

—ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING

Generation X-ers, those born in the 1960s and 1970s, have been said to lack the same over-the-top enthusiasm for social causes the preceding generation of boomers had. Instead, they were misunderstood and considered a disappointing group of potential slackers, seemingly cynical and apathetic toward everything. Before the Generation X crowd showed their true colors (such as virtually inventing the Internet and bringing the world into its current techno-savvy state), Kurt Cobain was one of the first to give a mainstream glimpse of what an X-er might look and act like. He defined an attitude of disenfranchisement while rising to the top of a musical movement termed Grunge, an offshoot of alternative rock. He appeared on stage in unkempt and multi-day slept-in wardrobes, stoned, wasted, blond hair straggly, though he was handsome and sensitive with large, doleful eyes; he became the new and more authentic image of the stoned-out rocker Generation X’s parents thought was all their own. Musically, Cobain combined heavy metal, punk rock, and a reinvention of classic rock riffs to create a new direction for popular music. His lyrics expressed the anger and dissatisfaction of being born into a time he and many in his age group found disconcerting—and he sold millions of records. He alternated from guitar-smashing, body-slamming rock to folk-like songs and personally hoped to move from the image of a Grunge rocker to a singer-songwriter, as he said, to become in old age like Johnny Cash.

From an early age Cobain displayed a rebellious streak that would make for a musical icon but one that would also lead to an unpleasant life. Cobain did not cope well with the divorce of his parents, in the early seventies when he was nine. Afterward, anger, disrespect for even the slightest smell of authority, and a distaste for adhering to any notion of conformity became trademarks of his personality. In his senior year, after he had been shuffled around from his parents’ and relatives’ homes, his mother threw him out of the house for good. He developed his grunge-style look the hard way, sleeping (he later claimed) under bridges or crashing out wherever he found a place to stay. He eventually gravitated to the Seattle music scene and formed the band Nirvana. The group’s struggles were typical of many, but by 1991 Cobain’s genius was noted and through luck, circumstance, and his dedication to something Cobain finally found he was good at and loved, Nirvana had a debut album distributed by a major label. It catapulted Cobain into stardom. He did not process success well, especially as he became enmeshed in the business side of the music industry that to him represented an antithesis to all the causes of individuality and rebellion he embraced. He felt uncomfortable when fans suddenly began to treat him, as he noted, “like some kind of god.” He started as a teen taking drugs, marijuana mostly, though later said, “I did heroin to relieve the pain.” Cobain believed he had an incurable stomach ailment, though it had no medical name.

I’m so happy because today I found my friends—they’re in my head.

—KURT COBAIN

His marriage to singer Courtney Love smacked of the same dysfunction, and though somewhat altered under the spotlight of rock’s craziness, was unbearably familiar to his childhood experiences. He planned on seeking a divorce, quitting the music business, and getting clean. Instead, in 1994, fresh out of a rehab, the twenty-seven-year-old rocker was found in his Seattle home dead with a shotgun wound to his head—discovered by his young daughter, no less. The autopsy found 225 milligrams of heroin in his blood, three times the amount needed for a lethal overdose. The hardest-core junkie would be immediately incapacitated after shooting that much dope, unable to hold a gun or fire it, which leads some to believe his death, although listed as suicide, has more sinister overtones.

All drugs, after a few months, become as boring as breathing air.

—KURT COBAIN

Cobain was beside himself when he learned that a woman was raped by a few idiots who admitted they did so while playing his song “Polly.” He also tried to conceal his drug habits from the press when he heard that heroin use among his fan base had increased by 25 percent in a two-year period, and made attempts to explain that there was nothing glamorous about a heroin addiction. When he died, there were many distraught admirers, but the saddest was the suicide pact a fourteen-and fifteen-year-old made soon after: Both boys were found dead in their suburban basement from self-inflicted shotgun wounds. A Middlesex County, New Jersey, prosecutor said, “There were signs the two were depressed and had sought help. But I guess it wasn’t enough.” Apparently, they couldn’t be dissuaded from imitating Cobain’s image and his comment made shortly before his own death: “Rather be dead than cool.”

It is not enough to have a good mind; the main thing is to use it well.

—RENÉ DESCARTES

As a child, famed Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was constantly belittled by his older brother Frank, to an extent that it now would be considered psychological abuse. Young Samuel sought refuge in a local library and there, it’s said, he taught himself to read the classics by the age of six. When he was nine years old his father died. Soon after, his mother thought it better to send him away to London to one of the most notoriously strict boarding schools in all of England. After that, he attended Cambridge University for a few years but dropped out and joined the military, though within months knew he had made a mistake and managed to get discharged, citing insanity. However, he was hardly insane, and possibly possessed one of the more astute minds of the era, called by his contemporaries, such as William Wordsworth, a “giant among dwarfs.” He had two fatal weaknesses, nevertheless: one was unrequited love, first his mother’s, and then that of Sara Hutchinson; the other was opium. He first took the drug as a medicine in the form of laudanum to ease the pain of a toothache when he was twenty-three years old. During the early stages of its use he produced his best and most-remembered works, namely Rime of The Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan, which he admitted were the result of an opium dream. He never left the drug completely alone again, though tried to quit often, alternately completing many other works. Today, he might be considered a “functional addict,” in that he continued to produce. Coleridge once mustered the discipline while high to put out more than twenty-five weekly issues of a newspaper, The Friend, from the end of 1809 through the spring of 1810. Although Coleridge is often praised for his output, in reality, the opium addiction ultimately shortened his attention span and eliminated the persistence he needed to fulfill the promise of his true genius. The ever-increasing quantities of laudanum he needed just to keep from falling immobile and ill changed him; this once formidable man of five feet ten inches, with broad shoulders, a shock of black hair, and strikingly large and piercing eyes, became a frail, bent-over skeleton of his former self. At the end, he consumed a quart a day of the drug that ultimately made him quarrelsome, isolated, and embittered. He prepared his own epitaph: “Beneath this sod a poet lies, [who] found death in life, may here find life in death.” He died in 1834 at the age of sixty-one of fluid on the lungs and heart failure due to opium abuse.

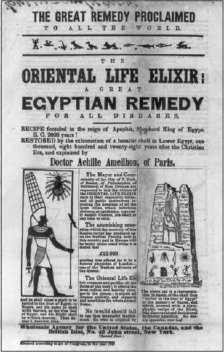

Laudanum was discovered by Swedish alchemist Philippus von Hohenheim in the 1500s.He combined various poisons to come up with an opium tincture he thought so wonderful he named the new drug “laudare,” a Latin word for “praise.” By Coleridge’s time there were dozens of different brands of laudanum elixirs, good for any ailment from the common cold to heart disease, and as one advertisement boasted, to simply, “check excessive secretions, and to support the system.” Charles Dickens took it after a difficult reading tour in America and started to write a novel under the influence, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, but never finished. Mary Todd Lincoln took it to relieve migraines. On the night President Lincoln was assassinated, the President planned to cancel the evening at the Ford Theatre due to Mary’s persistent headache. When at the last minute another bottle of laudanum was procured, she took a dose and felt well enough to attend. Without a bottle of laudanum in the mix, John Wilkes Booth’s plan would have failed.

During the 1800s tuberculosis made many ill, and to ease its symptoms, laudanum was dispensed widely, to adults and children alike. There was a sort of “tuberculosis chic” that crept into the culture and many who were not ill tried to have the pale and emaciated look that the truly dying acquired. Some women even took small doses of arsenic to get a gray-ashen pallor to their skin. People knew too much laudanum was bad, but still its rampant abuse cut across all classes. Many working women binged on a bottle of it at the end of a heavy work week as a sort of cheap vacation. The rich and well-to-do indulged as well. Many of the higher-class, refined ladies regularly stashed a small vial of it under their frills and petticoats. From the 1830s to 1900, the British imported twenty-two thousand tons of opium from Turkey and India every year.

A weakness natural to superior and to little men, when they have committed a fault, is to wish to make it pass as a work of genius.

—FRANÇOIS DE CHATEAUBRIAND

Strange that his father was the man responsible for inventing the candy known as “Life Savers” when in the end not the fortune the family earned nor the accolades of his peers could save this American poet from himself. Hart Crane published only two volumes of poetry in his lifetime, and they had many critics divided, with some important literary experts calling him the American Keats, while others panned his work as too difficult and doomed to obscurity. Signs of his rebellious streak surfaced early, as he dropped out of high school and headed to New York City as a teenager to seek adventure. Although he went back home and worked briefly writing ad copy for his father’s candy company, he preferred to drink and get into barroom brawls, often spending nights in jail. He was also reckless in his pursuit of men for homosexual encounters, particularly ones without those sexual leanings, which led to a number of bad beatings. He wrote letters to his concerned mother, explaining he acted this way to find “true freedom” she in turn sent more money when he went broke, which happened frequently.

When it came to his poetry, he felt it was his purpose in life to compose the greatest epic poem ever conceived. This calling was reinforced when he discovered what he called “the seventh heaven of consciousness” in, of all places, the dentist’s chair. Under the influence of nitrous oxide, he believed he heard a voice that revealed to Crane his uniqueness among men, due to his higher level of consciousness, and that he was, quite literally, a genius. He then went on to work at one poem for six years, even going to Paris, where he was put up and encouraged to carouse even more by the notoriously decadent Harry Crosby of the Black Sun Press. Meanwhile, his life, in contrast to the obsessed dedication to his writings, was chaotic and as far from any lyrical iambic pentameter as one could imagine. He struggled with immobilizing bouts of depression, not helped by his voluminous alcohol intake, or his distracting, often infatuated involvement he had in any number of failed love affairs, predominantly with sailors.

The form of my poem [The Bridge] rises out of a past that so overwhelms the present with its worth and vision that I’m at a loss to explain my delusion that there exist any real links between that past and a future worthy of it.

—HART CRANE

When his epic poem The Bridge was published it gathered mostly bad and crushing reviews that led Crane to believe he was ultimately a failure. Although Crane has since been appreciated as a genius—as Harold Bloom noted, “Crane was a consecrated poet before he was an adolescent”—the nearly unanimous critical disapproval devastated the poet. Nevertheless, Crane was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship and went to Mexico on their money with the intent to heal and write. But once there, he could not create. He tried to knock his homosexual desires out of himself by having his first heterosexual affair with the ex-wife of his close friend Malcolm Cowley. He also got word that his father died, and although counting on an inheritance, learned he was to get none. Crane panicked and gulped down a bottle of medicinal iodine, along with a fifth of Scotch (his favorite drink), but his new girlfriend found him unconscious and summoned help in time to pump his stomach. He considered himself beyond hopeless, since, even with a beautiful woman in love with and caring for him, he secretly had another homosexual affair. In the spring of 1932 at age thirty-two he boarded a streamliner, the S.S. Orizaba, heading back to New York. Within a few days he was beaten by a male sailor whom he’d offended by his sexual advances. Around noon the next day, he climbed the railing, and waved, saying, “Good-bye, everybody,” before he leaped overboard. Life savers, the real ones, were tossed his way, but the poet vanished under the waves in the Gulf of Mexico, and his body was never retrieved. A marker near his father’s grave reads “Harold Hart Crane—Lost at Sea,” without mention whether that was the true path to the seventh heaven of consciousness.

The bottom of the sea is cruel.

—HART CRANE

Psychologist James W. Pennebaker counted the number of pronouns in the works of many published poets. He concluded: “Suicidal poets use a large number of I’s and a low number of references to other people.” Regardless of the pronouns, the suicide rates are much higher among poets than all other types of authors.

The principal mark of genius is not perfection but originality, the opening of new frontiers.

—ARTHUR KOESTLER

Stephen Crane’s most famous book, The Red Badge of Courage, remains required reading on many school lists, but most classroom discussions sidestep the author’s advocacy of prostitutes’ rights, and that Crane even married the madam of a whorehouse to prove it.

He was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1871, the last of fourteen kids, which if nothing else speaks of the amazing durability of his mother. Nevertheless, it’s no wonder both parents died while Stephen was young. At nineteen he journeyed across the bay to New York City to seek his fame as a writer. There he found a raw pulse of life in the Bowery, when that area was truly rough, a haunt for streetwalkers, winos, and gangs. He had already made a reputation as what some call a “man’s man,” and was noted as an excellent bare-handed catcher in baseball. Crane took up the gambling, drinking, and smoking habits of someone twice his age. His self-published first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, about a hooker, was called offensive by critics, and the book flopped. Crane persisted. He received international acclaim at age twenty-five when The Red Badge of Courage hit the stands and was reprinted fourteen times in one year. Praise was lavished on Crane, including a detailed review in the New York Times that said, “he is certainly a young man of remarkable promise.” Crane wrote stories using detailed imagery, with a cinematic eye, long before movies were invented. Forever on the go, with one foot always out the door, he traveled widely, seeking authenticity by heading to trouble-spots to get a bird’s-eye view. When returning from one venture his boat sank, though miraculously he survived nearly thirty hours at sea until he washed ashore at Jacksonville, Florida. It was there he met and married the madam of the brothel called Hotel de Dream. His marriage to her outraged everyone, and Crane and his new bride sought solace in England, apparently then more accepting of the avant-garde. From the beginning, Crane’s writing habits were of one possessed, as if he were in a contest with himself to produce as much work as possible in the shortest amount of time. He was a notoriously poor speller and said he had no time to learn, knowing, perhaps, that the sand in his hourglass was quickly being depleted. Sure enough, with fountain pen to paper to the end, he burned out at age twenty-eight, dying of what reports variously said was tuberculosis, malaria, and possibly a venereal disease, in 1900.

Every sin is the result of collaboration.

—STEPHEN CRANE

Mediocrity is self-inflicted. Genius is self-bestowed.

—WALTER RUSSELL

Harry Crosby was the often forgotten member of the famed literary “lost generation” that gathered in Paris at the beginning of the twentieth century, and mingled with luminaries such as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Gertrude Stein. However, Crosby found a rather odd and fatal obsession to call his own. Born with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth, Crosby, of the Boston Brahmin class, with family ties to megamogul J. Pierpont Morgan, was educated at elite schools and assured a prosperous career in banking. The strikingly handsome young American aristocrat had other ideas and volunteered to drive a Red Cross ambulance during World War I. The experience of war, particularly the red glow of bursting bombs that left what he called “charred skeletons,” led him to believe that the power of the sun had to be worshiped and seized. His family knew something was amiss when he returned a war veteran who couldn’t stay sober and preferred to paint his fingernails black. They sent him to Paris in the hope he’d grow out of this foolery. Instead, there he took to heart the poet Rimbaud’s advice to find truth through the “disarrangement of the senses,” and Oscar Wilde’s admonishment to “succumb to every temptation.” Crosby’s Black Sun Press was extremely influential to literature, publishing the early works of future icons, including D. H. Lawrence, Hart Crane, and James Joyce, thus making Crosby a personality many struggling writers of his generation wanted to know. Crosby also used the press to publish his own books of poetry, but he left the details of running the press to his wife. Crosby preferred to spend his family’s stipend on caviar, champagne, cocaine, opium, and pretty women, and preferred to lounge many a day away wearing silk pajamas. When he published his poetry collection, Chariots of the Sun, he celebrated by having a giant sun tattooed on his back.

He didn’t keep his suicide-wish a secret and talked of little else but a glorious “sun-death,” setting fire to “the powder-house of our souls,” and going out with an explosive bang, instead of what friend and poet T. S. Eliot described as the more preferred whimper. At age thirty-one, Crosby and a lover were found in bed, both with bullet holes in their heads. Crosby’s pistol had a sun etched into the handle. The bodies were fully clothed, except for Crosby’s bare feet. On the soles he had tattooed a pagan sun that looked not at all fashionable next to the morgue’s tag dangling from a string around his big toe.

I have invited our little seamstress to take her thread and needle and sew our two mouths together.

—HARRY CROSBY

Although Crosby had a few tattoos, covering every inch of his body with them was not one of his obsessions. People inspired to use the body to display artworks and drawings flourished during his time, rivaling today’s current trend in tattoo popularity. Decorating the skin with permanent pigments dates back to fourth century BC, and has more or less gone in and out of favor ever since. A few people cover their entire bodies until every inch of the “canvas” is used up. In the late 1800s Alexandrinos Constentenus ended up with 388 inter-connecting tattoos and became the first person to make a living displaying his passion: billed as Captain Constentenus, he made the equivalent of a thousand dollars a week in P. T. Barnum’s sideshow. He had them on the eyelids, ears, the penis, and everywhere else, with dirty messages inked between his fingers. A known womanizer and heavy drinker, he got into trouble flirting with female clientele, exposing more than some wanted to see. His fate remains cloudy, though he supposedly went down to visit Greek family members he had in Tampa Bay and while diving for sponges was either eaten by sharks or drowned. Today, people with tattoos say it makes them feel sexier, although it depends on where it is and what it’s about, since certain tattoos are used for gang identifications, and more than 80 percent of those convicted for murder have at least two.