I think it takes obsession, takes searching for the details for any artist to be good.

—BARBRA STREISAND

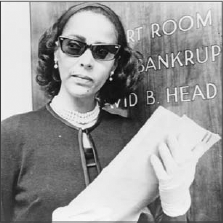

In 1954 Dorothy Dandridge was hailed by the New York Times as the most “beautiful Negro singer since Lena Horne.” In reality, the musical that made her famous, Carmen Jones, had dubbed over her voice with that of an opera singer. They did the same in her next musical, Porgy and Bess. She believed she had a good, soulful sound, though she admitted, “People just seem to like to look at me.” She had been in Hollywood since she was four years old, cast in a number of movies, and had remained diligent with singing, acting, and dancing lessons, always determined to make a name for herself. She started to sing professionally on the club circuit and picked it up again after her movie career began to fizzle. However, her short-lived heyday was grand: She was the first black female to be nominated for the Best Actress Oscar, in 1955, and the first to have her face on the cover of Life magazine, in addition to selling out performances in the U.S. and abroad. However, during the production of Carmen Jones Dandridge began an affair with director Otto Preminger that eventually proved to stifle her career and set off a cascade of events that would be her downfall. Although Preminger was married and would not divorce, he still wanted to retain control over Dandridge. Ultimately, at Preminger’s urging, Dorothy refused to take bigger film parts that would have established her film career. To make matters worse, Dorothy then married a restaurant owner who drained her accounts to keep his business afloat. By 1959 she was in debt, owing back taxes, had filed for bankruptcy, and moved into a small West Hollywood apartment, where she was alone. Still, she persisted and outwardly appeared determined to fulfill her obsession with stardom, though it was a deep hole to dig out of. In 1965, at age forty-two, she was found dead in her bathroom. At first, attempts were made by her manager and friends to say she died of an embolism caused by a broken ankle, since her foot was in a cast. However, months later, the coroner rectified the cause due to an overdose of Torfanil, an antidepressant, mixed, as it had been, with ever-increasing amounts of alcohol. Shortly before Dorothy died, she gave a forty-four-word, hand-written will to her manager, telling him that he’d be the one likely to find her: “In case of death—whomever discovers it—don’t remove anything I have on—scarf, gown, [word crossed out] or underwear. Cremate me right away. If I have anything, money, furniture give to my mother.” Dorothy only had two dollars in her bank account.

Unfortunately, mixing pills and drinking has been many female singers’ final note. Billie Holiday (forty-four), the soulful jazz singer, died handcuffed to a hospital bed from alcohol and heroin addictions in 1959. Dinah Washington (thirty-eight), called the Queen of the Blues, and Grammy winner for “What a Diff’rence a Day Makes,” one day in 1969 fatally mixed diet pills, booze, and sleeping pills. Judy Garland, with dual careers of acting and singing, like Dorothy Dandridge, died of what many called an accidental overdose. By 1969, Garland (forty-seven) had fallen deep into the bottle and the day she died had taken ten Seconals, when the normal dose is one. Florence Ballard (thirty-two) of the Supremes succumbed to complications of alcoholism and drug abuse in 1976. Candy Givens (thirty-seven) of the rock band Zephyr was loaded on alcohol and Quaaludes when she blacked out in a hot tub and drowned in 1984. Dalida (fifty-four), a popular European singer with eighty-six million records sold, was noted for releasing the first seventies French disco single, “J’Attendrai,” which was all the rage in clubs. She overdosed on barbiturates in 1986, leaving a note, “Life’s too unbearable.” Brenda Fassie (thirty-nine), dubbed “The Queen of African Pop,” born in Cape Town, South Africa, died in 2004 of alcohol and cocaine, after more than thirty failed stints in rehab.

Pride, envy, avarice—these are the sparks that have set on fire the hearts of all men.

—DANTE ALIGHIERI

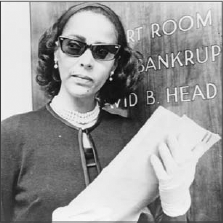

An obsession for pride is one way to make sense of Dante Alighieri’s life and death. This fourteenth-century poet and author of one of the most famous works of Western literature, The Divine Comedy, had the attribute in epic proportions. The Divine Comedy is a long epic poem describing Dante’s macabre journey through Hell and exploits in Purgatory and Paradise; similarly, Dante’s own life had been something of an odyssey. Caught up in the time of warring factions throughout Italy, Dante took part in battles and subversive plots to keep his place of position in his home city of Florence. As he wrote: “The hottest places in Hell are reserved for those who, in time of great moral crisis, maintain their neutrality.” Ultimately, he was on the losing end, exiled from the place that gave him identity, prestige, and money. At first, he would’ve been burned at the stake if he had returned to Florence, though later it became clear that he’d be pardoned if he paid a fine. His pride never allowed him to set foot in his native city again. Although he was married to another woman by arrangement, Dante loved one Beatrice Portinari, to whom he never did more than say hello. Dante became obsessed with her and made Beatrice his passion, the perfect ideal of beauty and love for the rest of his life. When she died at the age of twenty-four, he was nearly the same age.

There was such a forceful certainty in all Dante wrote that for centuries no one has ever doubted his greatness. It was this gargantuan-size pride that allowed him to boldly call and write what he saw as truth, yet it was the same that left him exiled and wandering, eventually succumbing to fever, probably from malaria. He refused medical advice, believing he knew better, dying at age fifty-six in 1321.

Lying in a featherbed will bring you no fame, nor staying beneath the quilt, and he who uses up his life without achieving fame leaves no more vestige of himself on Earth than smoke in the air or foam upon the water.

—DANTE ALIGHIERI

Al-Jahiz was a famous Arab writer and scholar in the eighth century. Despite humble origins, eking out an existence as a fish seller, he had a passion for knowledge, and eventually wrote encyclopedias on animals, social manners, stories, and history. Along the way he collected untold numbers of books and stocked an impressive private library. He died when a bookcase toppled over and crushed him.

The sin of pride may be a small or a great thing in someone’s life, and hurt vanity a passing pinprick, or a self-destroying or ever murderous obsession.

—IRIS MURDOCH

We know that the nature of genius is to provide idiots with ideas twenty years later.

—LOUIS ARAGON

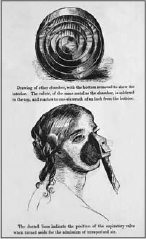

Salvino D’Armato, a glass craftsman in Florence, Italy, worked diligently to make a living providing colored shards used in stained-glass windows for cathedrals. He often held up pieces to a candle to test for purity. One day he examined a sliver of rejected glass, while by chance gazing through it at the fine-print design-drawing from which he worked. To his surprise, he was able to read the detailed instructions much more clearly. D’Armato suffered, as many in those times did who worked in poorly lit workshops, from what is now called hyperopia, or farsightedness. That day he had a stroke of genius and thought to choose similarly shaped convex glass scraps, and attach the pieces to a wad of beeswax that he stuck on the bridge of his nose. It looked ridiculous, but from then on D’Armato dedicated his life to perfecting what we now know as eyeglasses. At first he was thought an imbecile for purposely attempting to make what was considered inferior glass. When D’Armato began to fashion frames from the same lead that held stained-glass windows together, he was able to sell a few pairs. Before this, poor eyesight was treated with any number of lotions and concoctions that usually resulted in even worse sight. Lack of patent protection back then didn’t help the inventor’s fate, since by then there were a number of craftsmen inserting his glass into lightweight gold and silver frames that sold well. He died penniless at age forty-nine, in 1317, when, legend has it, he didn’t read the sign that warned against drinking at a contaminated well and succumbed to typhoid. Evidently, people thought he had other weaknesses than his obsession for invention, for an epitaph was written at the time of his death that read: “Inventor of Spectacles—May God forgive him his sins.”

Sunglasses were invented by Edwin H. Land in 1929 when he devised a polarizing filter to cut glare. He is primarily known as the genius behind instant Polaroid photography. Land apparently had a desire to keep things shady since to this day his death in 1991 cites merely “undisclosed causes.” In addition, his last wish instructed an assistant to shred all personal papers and notes.

To desire immortality is to desire the eternal perpetuation of a great mistake.

—ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER

Scottish poet and playwright John Davidson was noted for his keen and brilliant mind, and believed his entire life that people would eventually catch on to his genius. In March of 1909, he wrapped up his finished manuscript, grabbed his hat and cheerfully told his wife he was going to the post office to send it off before dinner. He was never seen again, and nothing but a package of old newspapers arrived at the publisher’s desk. Witnesses later said they saw Davidson stop in at the local bar for a shot of whiskey and a big cigar. He was last seen strolling down the road, puffing away contentedly on the stogie. His cheeriness was probably the first clue something was amiss, since the writer had grown perpetually bleak, depressed about his worsening financial situation. In addition, his recent philosophical views were being attacked after he had proclaimed that his life, and human existence in general, was one big joke with a bad punch line. He even complained about the duality of night and day, and that it was absurd for the days to separate in such a way, concluding that death was the only state that rectified life’s endless series of inconsistencies. Smoking a cigar might’ve been another clue, since his health had been seriously declining due to bronchitis and asthma. Nevertheless, the supposed sightings of John Davidson became a hot topic in newspapers until his body was found washed up on shore nearly six months later. That last evening he had apparently walked beyond the town to the cliffs of Penzance and threw himself into the English Channel. Though the scandal helped his last manuscript (discovered among his belongings), his final dramatic act never launched his work to the immortal status he had hoped.

Physical activity can get you going when you are immobilized. Get action in your life, and don’t just talk about it. Get into the arena!

—JOHN DAVIDSON

Although Davidson never took an IQ test he would’ve inevitably scored high; however, IQ scores and genius do not always mesh. The IQ test, first developed in the 1920s, was devised to measure the supposed mental age in ratio to chronological age, and to determine if children were mentally handicapped. A “normal” person will range between 85 and 110. It is estimated that only 1 percent of the more than six billion people on the planet have an IQ above 135, once considered the threshold for genius. Marie Curie was considered a genius, and won two Nobel prizes. She was passionate and persistent in working with radioactive isotopes, and although she had an astounding grasp on the entire concept, fell short in the ability to stop touching the stuff once she had seen how radiation affected her own body. She died of blood disorders compounded by radiation poisoning in 1934. John Stuart Mill, deemed a genius, wrote on logic, economics, and theories of government, women’s rights, and more. A forward thinker on liberty, he opposed the prohibition of alcohol and tobacco and died in 1873 of “lung congestion,” from smoking. Nevertheless, as psychologist Abbie F. Salny noted: “Genius may be in the eye of the beholder. Furthermore, a true genius may not score particularly well on a standard group IQ test. And really, those who are what we may call a genius don’t need a score to prove it.”

A legend is an old man with a cane known for what he used to do. I’m still doing it.

—MILES DAVIS

Miles Davis picked up a trumpet when he was thirteen, and within two years was considered a virtuoso. By the late 1940s, and lasting through the sixties, Davis was the most innovative musician on the jazz scene. Due primarily to a heroin addiction, and its aftermath, Davis’s appearances were infrequent during the last twenty years of his life. He died at age sixty-five in 1991, after a long bout of pneumonia and a stroke.

One science only will one genius fit: So vast is art, so narrow human wit.

—ALEXANDER POPE

Humphry Davy was a leading scientist and well-respected chemist of the early 1800s. Posterity recalls his role in the discovery of seven elements, and he was also known for giving well-attended lectures at the Royal Society of London on the early theories of electricity. Davy came from humble origins; he was a wood carver’s son who was apprenticed out to an apothecary’s shop, where he became interested in chemistry, and eventually made a favorable reputation for himself by being the guinea pig for many experiments. He was particularly interested in gases. Davy partook in one study to determine which was the better stimulant, alcohol or nitrous oxide. At the time it was believed alcohol was a stimulant, though it’s now known to be a depressant, while nitrous oxide was considered a trigger that allowed the user to experience an otherworldly and even spiritual clarity. He sat down in his lab and guzzled a large bottle of wine in seven minutes. He took notes as best he could as he lapsed into drunkenness. Then he inhaled five pints of nitrous oxide gas and promptly collapsed to the floor and remained in a blackout for two and a half hours. Still, in the name of science, he persisted in inhaling the gas in various quantities and eventually concluded that it was healthier than booze, since it didn’t leave the user with a hangover. In the process, however, Davy sadly became addicted. The papers he wrote, stating that the gas “made him dance around the laboratory as a madman, and has kept my spirits in a glow ever since,” set off a nitrous-mania among everyone from gentlemen and ladies to the town bloke. Davy even reported that the gas promoted longevity, even more so than oxygen, and wrote that nitrous oxide must be the air that is in heaven. As time went on Davy changed his public stance and told colleagues he had weaned himself from the stuff, noting that its use had seriously curtailed his scientific productivity. However, he admitted that the sight of an inhalation bag, or even the sound of a person laughing, triggered an insatiable, lifelong craving for the drug. Many biographical records have tidily cleaned up his episodes of relapse, preferring to remember him as the president of the Royal Society and as the humanitarian inventor who developed the first miner’s lamp, which Davy donated without seeking profit to help save lives. Yet his use of nitrous oxide and his penchant for inhaling all types of gases truncated and eventually extinguished the true potential of his genius. Before he died, at age fifty in 1829, he blamed his fatal illness on the “constant labour of experimenting, and the perpetual inhalation of the acid vapours of the laboratory.”

Other famous proponents of the use of nitrous oxide include Thesaurus author Peter Roget; Robert Southey, an English poet; Theodore Dreiser, an American novelist; William James, the philosopher; Winston Churchill, the English prime minister; and The Joker in Batman, whose most potent weapon was engulfing his adversaries in a deadly cloud of nitrous.

Opium teaches only one thing, which is that aside from physical suffering, there is nothing real.

—ANDRE MALRAUX

Thomas De Quincey was kept home in his childhood, considered too sickly and frail by his widowed mother to go out, and he was made accustomed to solitude, the house always as quiet as an empty church. Thomas read ferociously, devouring books and learning languages at such a pace that by the age of fifteen he was ready for Oxford University. But his mother decided that would make him too “big headed” and arranged to have his Oxford scholarship begin when he completed three years at a less prestigious grammar school. Restless, Thomas ran away after about a year and a half. He subsequently lived as a homeless teen, moving frequently, knowing his family was on the hunt for him, yet too fearful of his mother’s wrath to return. When they finally reconciled, Thomas was sent to Oxford, but after five years and no degree, he dropped out. During his college days he secured meetings with his literary heroes, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, through whom he was introduced to opium and laudanum. Thomas was a “super-senior” of sorts, hanging out at the campus, taking drugs, and hardly working until the age of thirty-one. After agreeing to marry a woman who bore a child (presumably his), his hyperactive creativity kicked into gear. He wrote as furiously as he read, publishing articles and translations at a rapid pace. One publisher noticed his apparent opium habit, and as a lark, suggested the spaced-out-looking writer do a piece on his opium experiences. De Quincey wrote a series of articles later collected into a book titled Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. The vivid descriptions of his bizarre opium dreams kicked off a dope fad, with all levels of society looking for a taste of the stuff. The book was a hit, and the biggest one he’d ever produce.

Whereas wine disorders the mental faculties, opium introduces amongst them the most exquisite order, legislation and harmony. Wine robs a man of self-possession; opium greatly invigorates it.

—THOMAS DE QUINCEY

De Quincey continued to churn out pieces on a variety of subjects, but his ever-growing habit took most of his income. Ten years to the day from the publication of Opium-Eater, De Quincey was sent to a debtor’s prison. Once out, he tried to slow his laudanum consumption, but soon he was again taking it to excess, which regrettably led to convictions for bad debt twice the next year and three more times the following year. His family life was intolerable, compounded by the ramifications of his addiction; he had three sons die, and finally his worn-out wife passed away from grief. During this period of funerals, De Quincey received a double conviction for more debt, which forced him into hiding much in the way he had spent his teenage years. When he was finally dragged before the magistrate, all agreed De Quincey had inflicted a punishment upon himself harsher than any court could conceive. He retired to a small cottage that he filled with books from floor to ceiling and labored in pin-drop quietude to complete a treatise on economics and a follow-up to Opium-Eater, which he titled Suspiria de Profundis. In the last years of his life a few editors sought him out—the way a relic from the sixties might be resurrected today— and a collection of his work was published to critical acclaim. De Quincey never stopped taking opium and died an old junkie at age seventy-three, in 1858.

The genesis for Confessions of an English Opium-Eater was first published as an article in the London Magazine in 1821, authored by an anonymous “X.Y.Z.” De Quincey had written it on the run, sick for many days from withdrawal symptoms—as he said, “ill from the effects of opium upon the liver”—though he persisted, writing it in coffee shops and taverns. A longer version was published as a book the following year and remained in print for the remainder of the century, influencing many writers and artists, and was supposedly a favorite of Edgar Allan Poe. The book was considered a medical treatise and was actually used as evidence in court cases to demonstrate certain effects of opium use.

Solitude, though it may be silent as light, is like light, the mightiest of agencies; for solitude is essential to man. All men come into this world alone and leave it alone.

—THOMAS DE QUINCEY

When De Quincey published Opium-Eater, the “English” part of his title was the novelty. The English government under its East India Trading Company had been growing tons of opium in India and trading it with the Chinese for tea and other commodities for nearly a century, helping more than a quarter of the Chinese population to become dope fiends. When the Chinese rulers tried to stem its use, banning its import, and dumping all seized supplies into the sea, British battleships appeared on the horizon. Resisting ports were devastated, and the superior British naval and land armies easily decimated the Chinese forces, who were using old-fashioned artillery and bamboo-lashed junks. The resulting peace treaty effectively allowed Britain to establish a preferential trade agreement with China and keep the opium flowing, although on a more hush-hush basis. In a sad irony, one of De Quincey’s sons was drafted into this war and died in the battle to keep opium trade routes open.

It was easy for poets and artists to get into debt, then and now, even without an addiction as money-consuming as De Quincey’s. English painter and writer Benjamin Haydon was close friends with William Wordsworth and among the top artistic notables of his day, painting portraits of Wordsworth and of John Keats—surely not the best-paying customers. Hayden called for poetry and writing to have a socially redeeming value rather than merely romantic images of flowers and such. He did a number of stints in prison as a result of his violent temper, which usually flared up against those trying to collect a debt. In the end he thought to go Shakespearean, and left a suicide note that quoted King Lear: “Stretch me no longer in this rough world.” The sixty-one-year-old disillusioned artist had had enough in 1846 and shot himself; when he didn’t bleed to death quickly enough, he then slit his wrists.

The lucky person passes for a genius.

—EURIPIDES

The fast and furious always grab attention. James Dean’s death at age twenty-four from a fatal crash while speeding in his Porsche remains the benchmark many thrillseekers still emulate. It’s arguable that Dean would’ve attained less notoriety if he hadn’t died young and been spared the fate of many actors with his talent who lived to be seen later in life filling a cube on Hollywood Squares. Elia Kazan, director of Dean’s film East of Eden, had to virtually lock up the young actor in a trailer during production to keep him from carousing all night and speeding on a motorcycle through the desert. The Academy Award–winning director said Dean had limited acting abilities, but worked hard, even if he was “highly neurotic.” Others disagreed, and saw him as possessing a natural genius for the craft. Dean came alive and was atypically animated when he talked about racing, and even participated in a number of professional racing events. Although his obsession for speed was the passion that would kill him, he looked forward to a successful acting career so he could buy more sports cars and motorcycles, and actually had “Dean’s Dilemma” painted on the side of one motorcycle. “Racing is the only time I feel whole,” Dean told a reporter for one of the many fan tabloids that relished the bad-boy eccentricities of this new sensation. James Dean’s mother died when he was nine, and he felt forever abandoned by her, as well as betrayed by his father’s decision to ship him back to the Indiana farmland where Dean’s mother was raised. He grew to be five-foot-seven, thin, with pale eyes and a small nose. At first he studied law at Santa Monica College but dropped out to pursue acting. Only East of Eden was released in his lifetime: Rebel Without a Cause and Giant premiered after his death, and he was nominated posthumously for Academy Awards for each. Dean died in 1955 from a head-on collision while driving in a Porsche 550 Spyder. A car speeding in the other direction crossed into Dean’s lane. Believing the driver would see him and swerve, Dean did not brake—a final game of “chicken.” According to psychologist Dr. Edward Diener, who conducted a study of what is called the “James Dean Effect,” some people “prefer shorter happier lives to longer ones.” It’s unlikely Dean would’ve agreed, although his untimely death in a fiery car crash assured his place in cinema history.

Dream as if you’ll live forever. Live as if you’ll die today.

—JAMES DEAN

I have three phobias which, could I mute them, would make my life as slick as a sonnet, but as dull as ditch water: I hate to go to bed, I hate to get up, and I hate to be alone.

—TALLULAH BANKHEAD

Emily Dickinson fascinates as much for her simple, pure, and thoroughly original American poetry as for her steadfast introversion and hermetic life. In her lifetime, she never published the more than seventeen hundred poems she hid under her bed, and she remains a beacon of hope for many an undiscovered poet who likewise wishes for posthumous notoriety. Emily was shy to the point of being agoraphobic. Although she did attend school away from home for a short time and went on a few other trips into neighboring Boston, she preferred the sanctuary of her parents’ home. As many agoraphobics are, Emily was very sociable to those who visited, even if, according to some accounts, during her later years she only conversed from behind slightly opened doors. More important than her phobias was her compulsion to write, coupled with an equal fixation for anonymity. She reportedly made some half-hearted attempts to find a place in print, but backed off at the first hint of criticism or revision. Her obsession to keep her work private and unaltered remains unusual, and has baffled more than a handful of scholars trying to make sense of her artistic anomaly. In the end, Emily never married, dying in 1886 at age fifty-five of a blood disorder, then cited as Bright’s disease, which is usually related to malfunctioning kidneys. It was the diagnosis du jour, though Emily was first thought to have “Domestic Illness.”

In the 1800s, “Domestic Illness” seemed to be the politically correct way to describe some sort of mental deterioration, often attributed to old age, or some unknown mania. Clues from death certificates that contain phrases such as “bedridden” or “hasn’t been out for years,” point to the possibility that Domestic Illness was cited for deaths from depression, Alzheimer’s, or Parkinson’s before those diseases were identified, or for any stroke victim—or agoraphobic—who was subsequently required to stay at home.

Emily had been treated with warm baths and given a tremendous amount of laxatives and diuretic tea concoctions, the standard treatment of the time, which surely did as much to kill her as the disease. She ended her days in fits of uncontrollable vomiting and high fever—and until her last breath kept the secret of her writing. When she died, her family was surprised to find more than forty carefully hand-bound books of her work amid her things. If it was fear of going out that kept her tethered to her home and gardens, it was a greater dread of rejection that kept her from pursuing publication, though there’s no doubt Emily dreamed in her private loneliness of a lasting notoriety and recognition of her work.

Because I could not stop for Death, He kindly stopped for me; The carriage held but just ourselves and Immortality.

—EMILY DICKINSON

A number of famous figures had phobias that influenced their life and work, and for the following theirs were greater than thanatophobia, defined as the fear of death and dying. President Ronald Reagan had aerophobia. He feared airborne noxious substances and drafts from windows: This might have attributed to his persistence and support for the “Star Wars” defense program, which aimed to knock flying objects from the sky. Benjamin Franklin had the opposite, and never slept with the window closed. Franklin died after catching a cold while sleeping in a room with the window open during the winter of 1790. Natalie Wood was hydrophobic, with a fear of water. This fact makes her drowning death in 1981 suspicious to some, especially since it was claimed she left a yacht after getting drunk for a solo sail in a raft. Napoleon Bonaparte had fear of cats, or ail-urophobia. When he died while confined to a prison, some said his death was due to stomach cancer, citing his drastic weight loss. But it was the herds of cats used to keep the prison rat population down that discombobulated him so much that he couldn’t eat. Adolf Hitler was claustrophobic, making his retreat to a bunker when facing defeat a more difficult one. That he took cyanide to commit suicide, and that he shot himself in the head rather than waiting for it to take effect, were motivated by his phobia.

What I like to drink most is wine that belongs to others.

—DIOGENES

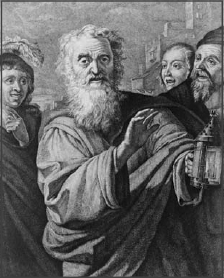

Diogenes of Sinope was a teenager when Socrates was charged and convicted of heresy, and had previously attended many of the great philosopher’s lectures. Shortly after Socrates’s demise, Diogenes sought another mentor, and though he failed, he did find a substitute of sorts: He became fascinated by watching dogs fornicate. He spent many hours on the street corners and back alleys observing their carefree behavior until he reached an epiphany, deciding that man’s four-legged friends had the answers to a happy life. Dogs, he observed, cared not where they slept or what they ate, and defecated whenever and wherever they wished. He began to act like a dog, crawling on all fours, living on the streets, and lifting his leg on any number of classical statues to relieve himself. Surprisingly, he wasn’t banished for madness, for when they accosted him, citizens were stunned when this filthy, dirt-covered man-dog began to discourse in elegant speeches. Diogenes believed man’s achievements were a sham and called all to follow his example, finding true freedom in a return to animality. He eventually gave up all possessions and lived in a broken barrel on the side of a temple. Diogenes’s legend spread far and wide, especially after he began to walk each night through the city holding up a torch, peering into the darkness. Without fail, many gathered around to see what he was looking for, and when finally asked, he always answered with the zinger: “I’m looking for one honest man.” Diogenes is credited with another original one liner. When Alexander the Great searched him out to hear his wisdom, he found Diogenes sitting on a hilltop, staring out into the horizon. Alexander reportedly offered to grant whatever Diogenes wished, and a large crowd waited in silence to hear his request. Finally, Diogenes looked up and said, “There is one thing you could do for me. You can step aside, you’re blocking my view.” In the end, some say Diogenes died holding his breath, believing he had grown too attached to air, while others insist he was bitten by a rabid dog. Nevertheless, his odd genius was honored with an apt monument—a pillar with a statue of a dog perched on top.

No one appreciates the very special genius of your conversation as the dog does.

—CHRISTOPHER MORLEY

Champion George was a famous pug that had his likeness painted on numerous products and advertising campaigns—one of the first to cash in on Americans’ love for dogs. George sat among his handlers and looked back and forth at conversations as if he understood what was said, and he is considered the inspiration for paintings that had dogs doing human things. George was noted for heading to the tavern, where he made a reputation for lapping up his daily mug of beer, and during one summer afternoon in 1892, died unexpectedly in Philadelphia of heat stroke at age twelve. Barry III, the St. Bernard that gave the breed the reputation for saving people in avalanches, always with a little keg of whiskey around his neck, did actually rescue untold lives in Switzerland’s Alps. He died in one attempt, trying to bring back hikers lost in a storm, in 1910. The hikers made it to safety but Barry couldn’t stop from seeking out others, and was buried alive. German Shepherds were used in World War I to help medical units. An American captain found a puppy of one of these dogs in a deserted German medic station. He brought it home and named it Rin Tin Tin. The dog was so smart it starred in twenty-six Warner Brothers movies, receiving more than ten thousand fan letters a week, and is credited with saving the studio from financial ruin. Treated like a diva, Rin Tin Tin dined on chef-prepared, bite-size-cut filet mignon while classical music was played to help him digest. The dog died in 1932 at age sixteen.

What is life? It is the little shadow which runs across the grass and loses itself in the sunset.

—CROWFOOT, A BLACKFOOT WARRIOR

Michael Dorris was focused on one small part of his lineage, the Native American blood in his veins, and used this passion to become a writer, spokesman and scholar for Native American causes. In the 1970s all things Native American were in popular demand, and Dorris took issues to heart by adopting a Native American boy suffering from Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS). Dorris further made news by becoming the first single male in America permitted to adopt a child of any origin. Dorris wrote a nonfiction account of his trials, The Broken Cord, that won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and brought much-needed attention to the dangers of drinking while pregnant and remains required reading. To further champion his cause, he adopted two more Native American children suffering from FAS. Dorris, if measured by his written words, was talented, and the public persona he so diligently crafted to publicize his books seemed, for decades, impeccable. However, his unraveling came fast and heatedly: His first adopted son died in a hit-and-run accident; his second adopted child brought him to court and sued for child abuse; his long-time wife filed for divorce, with her three daughters bringing sexual-molestation charges against him. He knew, as the onslaught began, that reputation more than talent would be behind the judgment cast on his legacy, and if anything, Dorris was obsessed with presenting a persona devoid of flaws. Facing divorce and accusations of child abuse are no small challenges for anyone, and it’s no wonder he tried to commit suicide on Good Friday.

After his first suicide attempt, Dorris spent time in a mental hospital, but on his first furlough he drove immediately to a nearby motel, took over-the-counter sleeping pills, drank vodka, and tied a plastic bag over his head. It could be argued that his obsession to maintain, at great cost to those closest to him, the public identity he had constructed, actually killed him at age fifty-two when the fiction irreparably fell apart. In his suicide note he apologized to the motel maid he knew would find him.

Whether Dorris was guilty of these transgressions remains unanswered, since gag orders were promptly enforced after his death in 1997. The lawyer, Lisa Wayne, who prosecuted Dorris said, “I feel like this suicide is a confession. Michael Dorris is talking to us from his grave.” Others said he was innocent.

Many new writers sit on the sidelines scratching their heads, wondering what they need, in addition to talent, to break into print. Considering the fact that an estimated one million manuscripts are at any given time floating through the mail vying for the attention of a major publisher, it makes sense for the persistent writer to focus on a niche. Whether it is, as it was for Michael Dorris, about Native Americans, or stories about zombies, or adolescent girls coming of age, the prospective author has a better chance when directing the work to a somewhat definable audience. However, once an author breaks into a niche, greater lengths are needed to stay there. One writer, Eugene Izzi, had found his place writing bestselling detective thrillers, and prided himself on striving for authenticity. Izzi knew the discerning crime reader would easily detect an implausible murder scenario and quickly send the author’s book to the bargain tables. Many believe his death, in 1996 at age thirty-three, was the result of overzealous research. The author was discovered hanging outside the fourteenth-floor window of the Chicago office building where he wrote. The rope wrapped around his neck was attached to the leg of his desk. After his corpse was reeled in, police discovered that Izzi was wearing a bullet-proof vest: a can of mace, brass knuckles, and a computer disk were also found in his pockets. The authorities ruled out homicide when they read an outline for the exact crime scene before them that Izzi had just written and saved on the floppy found on his person. Izzi was working out the details of how one could plausibly escape after an angry, militant militia stormed an office building. Apparently, his idea needed revision.

Whiskey and beer are for fools. Absinthe has the power of the magicians; it can wipe out or renew the past, and annul or foretell the future.

—ERNEST DOWSON

Ernest Dowson liked books, but not sitting in a classroom. He dropped out of Oxford in 1888 to work at his father’s prosperous dry-dock business down at the wharfs, and enjoyed being close to the pubs, where a mug of beer was the breakfast special. His father gave his rascal of a son flexible hours, which Ernest devoted to writing and carousing. Dowson was in the right time and place to become part of what was considered the Decadent Movement, filling the gap between the old-fashioned Romantic school and modern writers. He joined literary clubs and became chummy with up-and-coming notables, including William Butler Yeats, and for a spell joined Oscar Wilde’s flamboyant entourage. One slender book of verse was the only poetry he published in his lifetime, and it was recognized by his fellow writers for its genius. Leading English critic Arthur Symons praised Dowson’s literary brilliance for bridging the transition from pastoral literature to modern lyrical sensibilities, in addition to heralding Dowson as second in line, only after Oscar Wilde, as the greatest literary decadent of all time. Dowson’s poems not only urged the reader to find “madder music” and “stronger wine,” but a few of his lines remain popular in today’s lexicon, such as “days of wine and roses,” and “gone with the wind,” which Margaret Mitchell used for the title of her famous novel. Dowson’s success lasted only a few years, and his creativity reached its zenith when, at age twenty-three, he fell in love with an eleven-year-old girl, writing some of his best work to her. He tried to collaborate on novels or do translations to show that he could earn money from his writing, but found no commercial success. He traveled widely through Dublin, London, and Paris on his family’s considerable money until his ever-supportive dad got sick from tuberculosis. The senior Dowson decided not to endure a lingering death, and euthanized himself with an overdose of chloral hydrate. A month later, Dowson’s mother hanged herself. When Ernest discovered that the young girl he still pursued had been married off by her father to a tailor with better earning potential than a poet, Dowson was heartbroken. These multiple tragedies put an understandable damper on his carefree ways. His social drinking habits quickly advanced to the point that he was seldom seen sober. He eventually swore off beer and wine and switched to absinthe. A fellow writer friend found a barely recognizable Dowson penniless and begging for a drink in a bar. He took Dowson back to his cottage for recuperation, but the decadent poet was too far gone and died from complications of alcoholism at age thirty-two in 1900.

They are not long, the weeping and the laughter,

Love and desire and hate:

I think they have no portion in us after We pass the gate.

They are not long, the days of wine and roses; Out of a misty dream

Our path emerges for a while, then closes Within a dream.

—ERNEST DOWSON