Seven

Building on Vice

Building on Vice

The Sex Industry and the Creation of Georgian London

The built fabric of London, and the life lived within its buildings and streets, echoed to the motion and machination of the city’s sex trade. Virtually every part of the vast and sprawling organism of Georgian London had a role to play in what was now one of its most lucrative activities and many of its buildings were constructed, or leased, using money generated by the sex industry. The roles played by various locations evolved during the 150 years after 1680 as London grew and functions shifted, but the sex industry nevertheless remained citywide.

By 1700 the reconstruction of the City after the Great Fire of 1666 was mostly complete, and large industrial and maritime suburbs had spread to its north, east, and across the river in Southwark. The City was linked to Westminster by the important thoroughfare of trade and commerce running from the Royal Exchange, the Guildhall and Cheapside in the east, via Ludgate Hill, Fleet Street, Temple Bar and the Strand, to Charing Cross and St James’s Park in the west. During the seventeenth century much development had taken place to either side of this thoroughfare, especially around the Strand, and to the north of which Covent Garden and Seven Dials had taken form after 1630. This major east-west route was parallelled farther north by the similarly orientated but more meandering Great Ormond Street, Queen Square, Bloomsbury Square, Great Russell Street-axis that marked the northern extent of West London and which, in the late seventeenth century, had become a favoured location for new high-class developments.

By 1750 the balance of London had changed: the West End, in particular, had been developed prodigiously, shifting the heart of fashion further to the west and making Soho – where coherent development had started in the 1680s – a central rather than peripheral area, while to its north and east the City had greatly expanded with the development of extensive mercantile, manufacturing and industrial enclaves, such as the silk-trade area of Spitalfields and Shoreditch and the quays in Wapping and Limehouse.

The sex trade operated everywhere, with only the tone and type of its activities varying from location to location. Cheap bawdy-houses and tainted whores, for instance, tended to be found in poor areas such as Drury Lane, Seven Dials, St Giles and Whitechapel, while exclusive seraglios and ‘convents’ were located near the court in St James’s – for example, Elizabeth Needham’s establishment of the 1720s in Park Place, running between St James’s Street and Green Park, and four decades later Charlotte Hayes’ ‘nunnery’ in King’s Place, off Pall Mall.

Randolph Trumbach, in his seminal 1998 publication Sex and the Gender Revolution, offers a sexual geography of London which points out that although the trade remained ubiquitous, at different times various locations within the city played particularly prominent roles. Throughout the eighteenth century, for instance, the great business thoroughfare running west from the Royal Exchange and Cheapside via Ludgate Hill and Fleet Street to St James’s Park, thus linking the financial and trading centre of the City with the political power base of aristocratic West London, also became ‘the principal place for prostitutes to ply for customers’.1 It was perhaps predictable that this bustling route of commercial and political power also served as the main artery of London’s sex industry and the favoured domain of its legion of street-walkers.

Negotiating this thoroughfare then was a memorable experience, as Defoe explained in the 1720s:

With what impatience and Indignation have I walked from Charing-Cross to Ludgate, when being in full Speed upon important Business, I have every now and then been put to the Halt; sometimes by the full Encounter of an audacious Harlot, whose impudent Leer shewd she only stopp’d my Passage in order to draw my Observations to her; at other times by Twitches on the Sleeve. Lewd and ogling Salutations; and not infrequently by the more profligate Impudence of some Jades, who boldly dare to seize a Man by the Elbow, and make insolent Demands of Wine and Treats before they let him go.2

A scene described in the Grub Street Journal of 6 August 1730 may not have been entirely untypical of life encountered at certain hours along the thoroughfare: a group of women was ‘taken at 12 or 1 o’clock, exposing their nakedness in the open street to all passengers and using most abominable filthy expressions’.3 The group included Kate Hackabout, whose name, and perhaps manners, captured the interest of William Hogarth. A report in The Times confirms that by the late-eighteenth century little had changed in the Strand: ‘[T]he indecencies practiced by the crowds of prostitutes before Somerset-House every night, not only put modesty to the blush, but absolutely render it dangerous to pass.’4

Indictments against the proprietors of ‘disorderly houses’ in Westminster and Middlesex from 1720–9 help create an intriguing profile of London’s illicit sex life. Disorderly houses were not necessarily bawdy-houses, but most probably were, and these statistics show that this activity was focused in three distinct areas. Trumbach’s analysis of records reveals that Covent Garden and its immediate environs were the location of 71.1 per cent of the indictments (with 193 disorderly houses located in St Giles-in-the-Fields but only 1 in the parish of St Anne, Soho); the area around the periphery of the City contained 14.7 per cent of the houses mentioned in the indictments (with 39 in Cripplegate and Clerkenwell and 15 in Shoreditch), while the remaining 14.2 per cent of the indictments referred to houses in Whitechapel and Wapping (with 36 in the large parish of Stepney and 10 in St Mary, Whitechapel).5 This concentration of the trade is generally confirmed by recent research undertaken by Tony Henderson. He has traced the location of bawdy-houses prosecuted in City wards in three periods: 1710–49, 1750–89 and 1790–1829, and discovered that in Aldgate – representing a portion of what was Whitechapel – there was 1 bawdy-house in the first period, 12 in 1750–89 and 26 in 1790–1829. In Farringdon Without, including part of Clerkenwell, there were 70 in 1710–49, 44 in 1750–89 and 48 in 1790–1829.6

This disposition of bawdy-or disorderly houses, suggesting the locations of London’s busiest sex-trade areas, is slightly enlarged upon by evidence offered in 1770 by Sir John Fielding to a parliamentary committee pondering the policing of the capital. Fielding pointed out that ‘the great number of brothels and irregular taverns…kept by most abandoned characters such as bawds, thieves [and] receivers of stolen goods…and carried on without licence from the Magistrate are another great cause of robberies, burglaries and other disorders’. He then went on to locate the offending buildings and their quantity:

The principal of these houses are situate in Covent-garden, about thirty in St Mary-le-Strand, about twelve in St Martin’s in the vicinity of Covent-garden, about twelve in St Clements, five or six at Charing Cross, and in Hedge Lane about twenty; there are many more dispersed in different parts of Westminster, in Goodman’s-fields, and Whitechapel, many of which are remarkably infamous, and are the cause of disorders of every kind, shelters for bullies to protect prostitutes, and for thieves.7

This evidence confirms that the sex industry’s heart was Covent Garden and its neighbouring areas (Hedge Lane was just east of Leicester Square), where prostitution flourished alongside taverns, bagnios, theatres, coffee houses and jelly houses (popular gathering places for prostitutes, who would consume exotic jellies out of special jelly glasses). But from the mid-eighteenth century Soho and Marylebone (which hardly make an appearance in Trumbach’s 1720s statistics) increasingly became the favoured locations for hotel-like brothels and the homes of actresses, middling and superior prostitutes, and ‘kept’ women, with, most significantly, many of the prostitutes mentioned in the 1788 and 1793 editions of Harris’s List having Soho addresses.

Legal records and popular publications must be treated with extreme caution when used to draw up a profile of the sex trade in Georgian London because the grander of these establishments were so discreet they managed virtually to remain invisible and essentially above the law, so generally do not appear in legal documents. However, they were from time to time noted by curious foreign visitors. For example, in the early 1780s Archenholz observed that there were many…

…houses, situated in the neighbourhood of St James’s, where a great number [of courtesans] are kept for people of fashion [with] admission into these temples…so exorbitant…that the mob are entirely excluded. A little street called King’s Place is inhabited by nuns of this order alone, who live under the direction of several rich abbesses. You may see them superbly clothed at public places; and even those of the most expensive kind. Each of these convents has a carriage and servants in livery; for the ladies never deign to walk any where, but in the park [and] I have seen many people of rank walk with them in public, and allow them to take hold of their arms, in the most familiar manner.8

The Congratulatory Epistle from a Reformed Rake of 1758 offers its own view of the favoured haunts of London’s sex trade and indicates the moment when the industry started to embed itself in the relatively recently developed streets around Soho Square. The anonymous author states that it is now wrong to assume that a ‘search’ for prostitutes should be ‘limited’ to the familiar areas of Drury Lane, Bow Street, St Giles and Hedge Lane where ‘such Houses as Mrs Doug—s’s, Mrs Sh—ter’s, Mrs G—ld’s &c.&c.&c.’ could be found ‘when I indulged myself in the Follies and Vices of the Town’. These days, observed the author, ‘I apprehend these Houses are no longer kept open in the Purlieus of Covent-Garden for the Convenience of incontinent Passengers.’9 Where then had such establishments gone? Mostly to Soho – such as that of Mrs Goadby, who in about 1750 opened her pioneering Parisian-style seraglio in Berwick Street.

Interestingly, the difference between the manner in which the sex industry operated in Covent Garden and in Soho is still reflected in the surviving historical fabric. The long-time commercial and industrial nature of Covent Garden – moving from entertainment uses in the eighteenth century to those relating to the wholesale fruit, vegetable and flower markets as well as publishing – means that hardly any Georgian domestic buildings there retain their original ground floors or ornate doorcases. Most were long ago removed to accommodate shopfronts, tavern frontages or warehouse doors. On the other hand, the late-seventeenth-, eighteenth-and early-nineteenth-century houses of Soho – an area of discreet brothels that also retained a significant residential, if not wealthy, population – still contain many original ground-floor details.

A perhaps typical Soho-based prostitute was the literary-minded Bet Flint, who lived in Meard Street, Soho. The house in which she lodged during the 1760s in furnished rooms was constructed in 1732 by the speculative builder John Meard and still survives. It is now numbered 9 and is, as it happens, one of the few original houses in this largely intact early-Georgian street to have had a later shopfront inserted in its ground floor. Elizabeth Flint was a curious and now, sadly, obscure character. She was, according to Dr Johnson, ‘generally a slut and drunkard; occasionally whore and thief ’ but also ‘a fine character’, and he observed in reference to this Meard Street house that ‘Bet…had, however, genteel lodgings, a spinet on which she played, and a boy that walked before her chair’.10 Johnson had ‘literary’ dealings with Bet. As he explained to Mrs Piozzi, his friend and herself an able diarist:

Bet Flint wrote her own life, and called herself Cassandra, and it was in verse; it began:

When nature first ordained my birth

A diminutive I was born on earth.

And then I came from a dark abode,

Into a gay and gaudy world.

So Bet brought her verses to me to correct; but I gave her half-a-crown, and she liked it as well. Bet had a fine spirit.

Soho Square (looking north), built from the 1680s onwards, was well occupied throughout the eighteenth century and was an important centre for prostitution. Mrs Cornelys’ Carlisle House, the site of risqué masquerades, was on the east side of the square.

Sadly Bet’s verse autobiography was not completed, perhaps because she contrived to get herself arrested on the charge of stealing a counterpane from her landlord. This led to a sequence of events that delighted Johnson. Bet had, he said, ‘a spirit that could not be subdued’, so when she was obliged to go to gaol to await her trial ‘she ordered a sedan chair, and bid her footboy walk before her. However, the footboy proved refractory, for he was ashamed, though his mistress was not’. Bet was acquitted and Johnson recalled her saying, ‘“[S]o now the counterpane is my own, and now I’ll make a petticoat of it.” Oh! I loved Bet Flint.’11

Much of the Oxford Road (now Street) running east-west along the northern edge of Soho was appropriated by the sex trade as it became gradually built along and around during the eighteenth century. Humble developments such as Oxford Market and modest streets such as South Molton Street rapidly became the haunts of cheaper prostitutes. After 1750, as various estates developed the land to the north of the west half of Oxford Street, a whole new theatre for sex was created. The ‘New Buildings’, as the smart and discreet streets in Marylebone were known, soon became a favoured location, not for common street-walkers but for exclusive brothels, and the place of operations and residence of high-class courtesans.

In the 1780s Archenholz calculated that 30,000 prostitutes lived in Marylebone (perhaps a misprint in the 1789 edition for 13,000), of whom 1,700 inhabited whole houses; while the Gentleman’s Magazine observed in April 1795 that, ‘the affect of prostitution’ was not ‘confined to the more public streets in the metropolis’ but could be seen in one of its ‘most extensive parishes…Mary-la-bone whose increase has taken place within these few years’ owes ‘a very considerable part of [its] inhabitants to persons of this description’.12

A startling portrait of a brothel in Marylebone is included in Michael Ryan’s Prostitution in London of 1839. Marie Aubrey, a Frenchwoman, and her ‘paramour’ John Williams ‘kept’ a house in Seymour Place, Bryanston Square in the mid-1830s in which lived ‘about twelve or fourteen young females…mostly from France or Italy’ who had been enticed to London, under false pretences of respectable employment, and were held dependent and more or less as prisoners. The house was…

…an establishment of great notoriety, visited by some of the most distinguished foreigners and others, and carried on in a style little short of that observed in the richest and noblest families. The house consisted of twelve or fourteen rooms, besides those appropriate to domestic uses, each of which was genteelly and fashionably furnished. The saloon, a very large room, was elegantly fitted up; – profusion of valuable and splendid paintings decorated its walls, and its furniture was of a costly description. As a necessary appendage, there was a small room on the ground floor appropriated as a counting house; a service of solid silver plate was ordinarily in use when the visitors required it, which was the property of Marie Aubrey.13

The 1788 edition of Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies recognised the new role of Marylebone while also confirming the lasting importance of more traditional locations: ‘Marybone…now the grand paradise of Love’ was placed alongside ‘Covent Garden, her elder sister’, while ‘antient Drury…Bagnigge, St George’s Spa…deal out each night their choicest gifts of love’. The List also recommended to the ‘sons of pleasure…the purlieus of White Chapel, The Royalty…Wapping and Shadwell’.

The part of town south and west of Covent Garden was a place of ancient and notorious repute – the Strand and the area around Charing Cross and St Martin’s-in-the-Fields were favoured pick-up spots for common street prostitutes who would take their clients into the system of alleys off the Strand or else the shady bowers of nearby St James’s Park. James Boswell, as he recounted in his London Journal of 1762–3, made use of both locations, and in his descriptions reveals much about the al fresco nature of the lower levels of the mid-eighteenth-century sex industry:

I picked up a girl in the Strand; went into a court with intention to enjoy her in armour [a condom made of sheep’s gut]. But she had none. I toyed with her. She wondered at my size, and said if I ever took a girl’s maidenhood, I would make her squeak. I gave her a shilling, and had command enough of myself to go without touching her. I afterwards trembled at the danger I had escaped.14

Charged with the sexual thrill of the rough and tumble of public sex among the lower orders, Boswell on another occasion went to St James’s Park and:

…picked up a low brimstone [i.e. a tough whore], called myself a barber and agreed with her for sixpence, went to the bottom of the Park arm in arm, and dipped my machine in the Canal and performed most manfully…In the Strand I picked up a little profligate wretch and gave her sixpence. She allowed me entrance. But the miscreant refused me performance. I was much stronger than her, and volens nolens [whether she wanted to or not], pushed her up against the wall. She, however, gave a sudden spring from me; and screaming out, a parcel of more whores and soldiers came to her relief. ‘Brother soldiers,’ said I, ‘should not a half-pay officer roger for sixpence? And here has she used me so.’ I got them on my side, and I abused her in blackguard style, and then left them.15

Charing Cross, looking towards the Strand, in c. 1730–40, as shown in a nineteenth-century engraving. This was one of the most important street junctions in London, until finally swept away in the nineteenth century for the creation of Trafalgar Square. It marked the end of the great commercial thoroughfare which led west from the City and was a pivotal point of the sex industry.

Francis Place, a radical and an acute social observer who ran a tailor’s shop in the Strand, described his immediate surroundings and nearby Charing Cross in the first decade of the nineteenth century and paints a clear picture of life in one of central London’s poorer and least-regulated sex districts:

On the eastern side [of Charing Cross] was Johnson’s Court [containing] 13 houses…all in a state of great dilapidation, in every room in every house excepting one only lived one or more common prostitutes of the most wretched description…the place could not be outdone in infamy and indecency by any place in London. The manner in which many of the drunken filthy young prostitutes behaved is not describable nor would it be believed were it described.

Place then goes on to describe the ‘low brothels’ with which his shop was surrounded, the ‘dirty Gin Shop…frequented by prostitutes and soldiers’, and – most startling of all – an old wall at nearby Privy Gardens which each night was patrolled by a ‘horribly ragged, dirty and disgusting…set of prostitutes’ who ‘used to take any customer who would pay twopence, behind the wall’.16

The streets and courts north of Charing Cross, around the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, seem to have been a favourite location for the trade in children. They would be offered as ‘apprentices’ to ‘masters’ in exchange for ready cash with no questions asked. The sex industry that flourished along the Strand continued east along Fleet Street, a location famed for its multiplicity of patrolling harlots as was made clear in the opening pages of Pretty Doings in a Protestant Nation of 1734 in which the author claims that ‘Where the Devil do all those B—ches come from?’ was a common Fleet Street phrase.17 And as early as 1699 Ned Ward in the London Spy described Salisbury Court – also referred to as ‘Sodom’ – off Fleet Street as ‘a Corporation of Whores, Coiners, Highway-men, Pickpockets and House-Breakers’.18

But Francis Place, when describing something of the character of the Fleet Street sex trade in the late 1780s, implies that the harlots here were not as poor, lurid or alarming as those stationed along the Strand and around Charing Cross. While an apprentice to a maker of leather breeches, Price, with his fellow apprentices, spent much time with ‘the prostitutes who walked Fleet Street’ and found them honest and even generous:

It may seem strange but it is true, that on no occasion did I ever hear one of these women urge any one of these youths to bring her more money than he seemed willing to part from…the women were generally as willing as the lads to spend money when they were flush. With these youths and these women I sometimes spent the evening eating and drinking at a public house…and never had any serious quarrel with any one of my companions.19

Fleet Street and Shoe Lane, with their network of dark and narrow alleys even more labyrinthine than those off the Strand, were the perfect terrain for those operating on the cheaper, potentially criminal side of London’s sex industry, as the Blewit/Hartrey case makes clear. It was to lodgings and bawdy-houses secreted in these alleys that the harlots took their clients and, incredibly, some highly ephemeral artefacts survive that identify an existing building as once part of Georgian London’s sex industry and suggest the manner in which a bawdy-house may have been furnished.

In Wine Office Court, north of Fleet Street, stands the Cheshire Cheese Tavern. Its architecture and details suggest it was purpose-built in the second half of the seventeenth century although much altered in c.1755. Its ground-floor fireplaces are unusual and especially indicative – their chimney breasts are supported on massive stone corbels which allow heat from the hearth to radiate in a 180-degree arc, something highly desirable in a public room with many people gathered around the fire and a detail found only in late-seventeenth-and early-eighteenth-century taverns (for example the Owl and Pussycat in Redchurch Street, Shoreditch).

In 1962 the Museum of London was presented with eight plaster of Paris bas-relief panels taken from the Cheshire Cheese, some intact, others only fragmentary, each originally measuring around 200 x 160 mm, which show men and women involved in a variety of sexual activities. Costume detail suggests a date of 1740–50, as do the French Rococo-style chairs and stools on which some of the figures sit, which might also be evidence that the panels were cast from moulds made in France.

A fragment of a plaster panel of c.1740–50 from the Cheshire Cheese Tavern, Fleet Street, showing a pair of prostitutes. One is giving pleasure to a client with a birch.

Those which are intact or easy to read show, for instance, a woman sitting on a stool – naked apart from stockings and a disarranged shift revealing her bare breasts – being penetrated by a man whose breeches are around his knees. Another intact panel shows a similar scene but with the man sitting on a chair, while yet another depicts a woman bending over and being penetrated from behind, although presumably not anally. Of this panel the Museum of London observes, the ‘blunt-toed shoes imply the scene is after 1740’.

These are very orthodox sexual activities. Slightly more imaginative is the fragment showing a threesome with a standing man, naked from the waist down, being flagellated and masturbated by two kneeling women, and a partially destroyed panel showing a figure reclining on the ground while pulling on a basket in which sits another figure – whose sex is unclear – being penetrated by the reclining figure which is smiling with pleasure in a slightly unsettling manner. Intriguingly, one pair of expert observers have described this scene as a woman lying prostrate, wearing a bonnet and a dildo, and that it is a man being lowered in the basket.20

Two further plaster panels from the Cheshire Cheese Tavern.

The unlikely and athletic nature of this scene is reminiscent of the notorious and highly influential ‘sixteen postures’ drawn by Giulio Romano in Italy in the early sixteenth century that were each accompanied by a sonnet penned by Pietro Aretino. Other fragments are hard to make out, but one shows the top half of a man’s body – wearing a tie wig and a blissful expression – framed by the naked legs of a woman. Some of the panels are soot-stained and the Museum of London records that they came from a second-floor room on the south side. The Cheshire Cheese remains in business but this room is not open to the public.

With some imagination it is possible to reconstruct the scene. The panels are much too erotic ever to have decorated a conventional domestic interior so they must have been from a room used by prostitutes or that was in some way involved in the sex industry. The Cheshire Cheese is first recorded in the 1760s and before that the White Horse Inn occupied part of the site but the simplest explanation is that the taverns didn’t run a bawdy-house on their upper floor but let the rooms to someone who did, or perhaps the room was used by a gentleman’s dining club of a particularly libidinous type. Intriguingly, an article in the Gazetteer of 18 October 1760, covering the suspicious death of the young prostitute Ann Bell, mentions the fact that she lodged with Mrs Jane Mead in Wine-Office Court, Fleet Street. Was Jane Mead a bawd, and were the upper floors of the Cheshire Cheese her bawdy-house? If so, then the tiles must have lined the inner cheeks of a fire-opening, with the scenes they depicted flickering and dancing by the light of flames in a very lifelike manner. The purpose of the panels was probably no more than is obvious and very similar to the numerous erotic images found in bath houses, private houses and a brothel in Pompeii – to titillate, inflame and inspire the imagination of customers and get them into an excited frame of mind when they’d be willing to pay good money for satisfaction.

But what is perhaps most extraordinary about these panels is that they were not made to last nor would they have been expensive to purchase. They are mass-produced ephemera that could have been fixed within the fire-opening in a few hours and, accompanied by a few well-chosen prints and erotic porcelain or earthenware (the Museum of London also has a Delft-made phallus in its collection), show how an ordinary room could have been transformed into a bawdy-house interior quickly and cheaply. The fact that such fragile items have survived for around 250 years to tell their tale is nothing short of phenomenal.21

St Clement Dane’s Church at the junction of the Strand and Fleet Street – a major landmark on the city’s sexual highway from the Royal Exchange in the east to St James’s Park and Charing Cross in the west.

The junction of the two ancient thoroughfares of the Strand and Fleet Street – the area around St Clement Dane’s Church – was for much of the Georgian period a notorious homosexual pick-up point. Indeed homosexual liaison seems, in the first part of the eighteenth century, to have been something of a City speciality, although a 1726 edition of the British Gazetteer suggested further locations when it reported that in addition to twenty Molly Houses – as homosexual taverns were called – being broken up, a stop had also been put to ‘nocturnal assemblies in the Royal Exchange, Moorfields, Lincoln’s Inn, the south side of St James’s Park and Covent Garden Piazza’.22

The Royal Exchange in the heart of the City, with its shady arcades and throng of waterside labourers – called ‘water rats’ – offering themselves for hire, was a particularly attractive gathering place for homosexuals in the early eighteenth century. In 1699 the London Spy described a City outing: ‘[W]e…went on the ’Change, turn’d to the Right, and Jostled in amongst a parcel of Swarthy Buggerantoes, Preternatural Fornicators, as my Friend call’d them, who would Ogle a Handsome Young Man with as much Lust, as a True-bred English Whoremaster would gaze upon a Beautiful Virgin.’23

The Barbican and the central portion of Cheapside were also particularly popular cruising grounds for homosexuals,24 while St Paul’s Cathedral and the courts and alleys immediately around it were favoured locations not just for meeting and homosexual intrigue but also, it seems, for extramural sex. A notorious location seems to have been the alley to the north of the cathedral’s still surviving Chapter House, perhaps because it was both screened and easy to escape from.

Another well-known pick-up place was called ‘Sodomite’s Walk’, which, according to Old Bailey trial proceedings for July 1726, was located ‘on Upper Moorfield by the side of the Wall that joins to the Watch-house and part of the upper Field’.25 Before development encroached on the area in the late eighteenth century and Finsbury Square was created from 1779–90, Moorfields was large in extent – comprising Moor Fields, to its north Middle Moor Fields, and then north again Upper Moor Fields, the northern boundary of which was the thoroughfare now known as Worship Street. According to John Rocque’s London map of 1746, Middle and Upper Moor Fields were divided by a wall with a watch house at its east end. This wall, now commemorated by the southern edge of Finsbury Square, was presumably the location of ‘Sodomite’s Walk’. The same Old Bailey trial report confirms the notoriety of the Walk and suggests that the use of agents provocateurs was accepted practice for ensnaring homosexuals here.

Molly Houses flourished around Field Lane and Saffron Hill in Holborn, just to the west of Smithfield, which, with neighbouring Cowcross Street, had been one of the centres of London’s medieval and Tudor sex industry – the illicit corollary to the ancient and from the mid-twelfth to mid-sixteenth centuries legally sanctioned sex quarter just south of the Thames around Borough and Bankside. The Thames, or at least the seafaring neighbourhoods along its banks, was long associated with London’s sex trade. The maritime areas of Wapping and Rotherhithe were notorious for their cheap prostitutes serving seamen, while the Ratcliffe Highway, running parallel with the Thames and east from the Tower and East Smithfield towards Shadwell and Limehouse, was well stocked with taverns and bawdy-houses, providing the East End’s equivalent to Covent Garden and the Strand, supplemented by what in 1787 Sir John Hawkins called the ‘halo of brothels’ that surrounded the theatre district of Goodman’s Fields at Aldgate and Whitechapel.26

The flavour of this maritime prostitution is well evoked by Francis Place. In the late 1780s he and his friends ‘spent many evenings at the dirty public houses’ frequented by the poor prostitutes who worked in and around St Catherine’s Lane, just east of the Tower. Place, who knew London well, was so astonished by what he saw here that he described the women as if they came not from his own city but from another and alien world:

…they wore long quartered shoes and large buckles, most of them had clean stockings and shoes, because it was for them the fashion to be flashy about the heels, but many had ragged dirty shoes and stockings and some no stockings at all…many of that time wore no stays, their gowns were low round the neck and open in front, those who wore handkerchiefs had them always open in front to expose their breasts…but numbers wore no handkerchiefs at all…and the breasts of many hung down in a most disgusting manner, their hair among the generality was straight and ‘hung in rat tails’ over their eyes and was filled with lice.

And the wary Place noted that ‘drunkenness was common to them all and at all times’ as was fighting ‘among themselves as well as with the men’, so that ‘black eyes might be seen on a great many’.27

Female violence was indeed a standard component of low-life prostitution in London’s more dark and dangerous areas. Hockley-in-the-Hole in Clerkenwell was the location of a variety of exotic, savage and exciting activities that were peripherally part of the sex industry and certainly attractions for prostitutes plying their trade. These events included bear and bull baiting, wrestling, boxing, and all manner of martial arts including sword-fighting contests – a broadsword contest between an Englishman and a Moor in 1710 is described by Baron von Uffenbach.28 Also, from time to time, bloody contests would be staged between bare-chested female pugilists. In the London Journal of June 1722, John Trenchard, when discussing boxing matches in London, reported that ‘two of the feminine gender appeared for the first time on the theatre of war at Hockley-in-the-Hole, and maintained the battle with great valour for a long time, to the no small satisfaction of the spectators’. The main protagonist was Elizabeth Wilkinson of Clerkenwell who ‘challenged and invited’ Hannah Hyfield to meet her on the stage for 3 guineas. The fighters were to hold half-a-crown in each hand and the first to drop a coin – which must also have helped to make each punch harder – would lose the contest. Wilkinson won, and seems to have been a regular pugilist for soon afterward she beat a woman from Billingsgate.

More conventional displays of the martial arts – with small broadswords, rapier, quarterstaff, cudgel and fists – were organised by James Figg, who from 1720 presided over the ‘Boarded House’ in the Bear Garden, Marylebone Fields. Figg was England’s first recognised boxing champion and impresario, and such was his fame that Hogarth painted his portrait and designed his business card. James Figg and his fellow masters of the arts of defence were much admired in early-Georgian London. They were seen as tough and brave men of honour. As Mrs Peachum told Filch in The Beggar’s Opera, ‘[Y]ou must go to Hockley-in-the-Hole and Marybone, child, to learn valour.’

Covent Garden and Jack Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies

However many new and different areas of London came to prominence during the eighteenth century as centres of the sex trade, Covent Garden retained its reputation as a flesh-market. This fact is constantly confirmed by contemporary eyewitness accounts and also by one of the most remarkable publications of the age, Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies. This directory of London prostitutes seems to have been started in the late 1740s by Jack Harris (a.k.a. John Harrison), a pimp and ‘head-waiter’ at the Shakespeare’s Head Tavern in Covent Garden, and by the hack writer Sam Derrick, who was in 1761, improbably, to replace ‘Beau’ Nash as Master or Ceremonies in the ultimate pleasure ground of Bath.

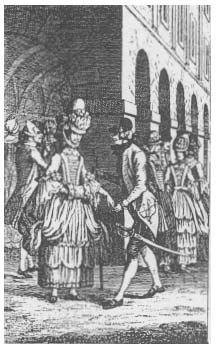

The frontispiece for the 1773 edition of Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies. It shows a harlot, in Covent Garden, displaying a handsome pair of ankles and accepting money from a client.

The first editions were no more than handwritten manuscripts kept by Harris for easy reference, but printed editions for sale, with pithy and often witty and ribald texts, appeared from the late 1750s and were regularly updated.29 The anonymously written A Congratulatory Epistle from a Reformed Rake of 1758 offers an account of these early Lists and something of a ‘user’s’ appreciation:

Passing an evening, a few weeks ago, at a certain Tavern near Covent-Garden [we] rung for the Gentleman-porter and actually asked him if he could get…some girls; to my great surprise he pulled out a List, containing the Names of near four Hundred, alphabetically ranged, with an account of their Persons, Age, qualifications, and Places of Abode…Believe it who will (for it is scarce credible) among these four Hundred Whores, near a Hundred were marked in the Margin as living in Bow-street, and the Courts adjacent, and upwards of half the rest, in about Covent-Garden. A Blood in Company began to question Bob, concerning his Catalogue, ‘What new faces have you got Bob?’ – ‘Please your Honour, I’ve nothing very new, withal ’tis Nancy Wilson – but she has just got hold of an Oxford Scholar worth sixteen thousand…’ ‘What else have you got worth looking at?’ – ‘Why an’ please you – there is Jenny Belse, and Polly Martin, – fresh out of keeping in Bow-street…’

And a list of girls are named, with Bob promising to have…

…next week two of the finest Girls in England, that have not been debouched above a Fortnight – Mrs D—g—s expects ’em in Town every day from Salisbury…Thus…did this audacious Pimp harangue, and talk of Covent-Garden and Bow-street, as if those Places were entirely over-run with Bawds and Whores…30

The early editions of the List include the names of women who were to become the leading courtesans of late-eighteenth-century London, including in the 1761 edition Lucy Cooper and Kitty Fisher. But perhaps the most intriguing of all the future high courtesans that Harris listed was Fanny Murray. So famous a character did she become that various memoirs and accounts of her life were published, from which we not only learn of her first encounter with Harris but also receive an insight into his working methods and relationship with the prostitutes he promoted.

According to the Memoirs of the Celebrated Miss Fanny Murray of 1759 she was born in Bath in 1729, orphaned by the age of twelve when she commenced working as a ‘retail merchant of nose-gays and bath rings at the rooms’, was soon seduced ‘by the celebrated Jack (Spencer) of libertine memory’ (the son of the 3rd Earl of Sunderland and grandson of the Duke of Marlborough, eventually the father of the 1st Earl Spencer and one of the supporters in 1739 of the foundation of the Foundling Hospital), and then at the age of about thirteen taken up by the nearly seventy-year-old Richard ‘Beau’ Nash – the City’s famed Master of Ceremonies. At this time, roughly 1742, the Memoirs note that Fanny’s personality was ‘gay [and] volatile’ and her…

…person…extremely beautiful; her face a perfect oval, with eyes that conversed love, and every other feature in agreeable symmetry. Her dimpled cheek alone might have captivated, if a smile that gave it existence, did not display such other charms as shared the conquest. Her teeth regular, small, and perfectly white, coral lips and chestnut hair.

Bath soon became too small a place for such a precociously experienced beauty and Fanny moved to London, away from her elderly protector and into the potentially dangerous and dark world of free-booting whoredom. Presumably she was in search of thrills, freedom and riches. It was a huge gamble. Naturally she gravitated to Covent Garden and seems rapidly to have ingratiated herself with the ‘Pimp-master General’, Jack Harris. The Memoirs make clear what happened next.

Notwithstanding Fanny’s extensive commerce, Mr H—s, the celebrated negociator in women, applied to get her enrolled upon his parchment list, as a new face; though, properly speaking, she had now been upon the town [that is, working as a whore in Bath] near four years. However, the ceremony was performed with all the punctilios attending that great institution; a surgeon being present for a complete examination of her person, and to report her well or ill, and a lawyer to ingross her name, &c. after having signed a written agreement, to forfeit twenty pounds, if she gave the negociator a wrong information concerning the state of her health in every particular. Then her name as ingrossed upon a whole skin of parchment.31

At this date, roughly 1747/8, Harris’s List was still issued in manuscript form and no early copies are known to survive, but the Memoirs contain the text of the supposed entry describing Fanny and offering her on the market:

Condition: perfectly sound wind and limb. Description: A fine brown girl, rising 19 years next season. A good side-box piece – and will shew well in the flesh market – wear well – may be put off for a virgin any time these 12 months – never common this side of Temple-Bar, but for six months. Fit for high keeping with a Jew merchant – N.B. a good praemium from ditto – Then the run of the house – and if she keeps out of the Lock, may make her fortune, and ruin half the town. Place of abode: the first floor at Mrs—’s, a milliner at Charing Cross.

Hallie Rubenhold has made a good job of decoding this entry.32 For example, ‘side-box piece’ refers to the type of ornamental prostitute found sitting in the side boxes at the theatre, and the reference to Temple Bar – the traditional boundary between the City and the West End – meant that Fanny was a new face in Covent Garden. The ‘good praemium’ refers to the high sum that a rich ‘Jew merchant’ (sought after as generous, kind and reliable clients) might be persuaded to pay above the odds for the pleasure of relieving Fanny of her ‘virginity’ – which would have been ‘restored’ many times during her first twelve months in town.

Appearing on Harris’s List and enjoying his patronage seemed to work for Fanny because, as the Memoirs explain, ‘[A]fter being thus initiated in the arcanum of Mr H—r—s’s system of fornication, she plied regularly in the flesh-market at the houses during the season by which means she increased the price of her favours, never now receiving under two guineas.’33

The ladies on Harris’s List had to pay for the business it brought them and the Memoirs contain a passage explaining the deal they struck with him. The arrangement described is picturesque and titillating and clearly calculated to amuse and arouse – the Memoirs were, after all, intended to be a softly erotic read. Of course they can’t be taken as absolute fact but there is, in all probability, more than a grain of truth in the system and practices described.

Fanny, we are told, was soon introduced to the ‘Whores Club which assembled every Sunday evening near Covent-garden, to talk over their various successes, compare notes, and canvass the most probable means of improving them the week following’. The ‘Whores Club’ had a long list of rules and, in describing these, the anonymous author of the Memoirs gives full rein to sexual fantasy. Every member of the club must, we are told, ‘have been debauched before she was 15’ and must be on Harris’s List, while any member ‘who may become with child’ was to be struck off for ‘no longer coming under denomination of a whore’. Each member was to pay half-a-crown for the support of fellow members in distress, and no man was to be admitted to the ladies’ club-room but ‘our negociator…who has the privilege of chusing what member he pleases for his bedfellow that night, she not being pre-arranged’.

The Memoirs also state that the club had about a hundred members, some of ‘noble families, and most of them of creditable and honest parents’. One of the main purposes of club gatherings was to allow the whores to clear ‘their arrears with their factor Mr H—s, who had five shillings in the pound freight for conveying them to the arms of their enamorato’s’. So for the good publicity that went with their ‘listing’, the harlots were obliged to pay Harris a ‘poundage’ of 25 per cent of their earnings. (This seems highly unlikely unless the charge applied only to the girls living and working under his immediate protection, and so also covered accommodation, food and various services.)

A humorous anecdote included in the Memoirs throws a little light on how Harris’ money-spinning ‘system of fornication’ worked. We are told a certain ‘Doctor Wagtail’ lit upon Fanny one night in Drury Lane and carried her to the Shakespeare’s Head Tavern. They entered a private room and Fanny desired him ‘…as he was an entire stranger, to make her a present before-hand’. He agreed, but had only five shillings and sixpence on him. Fanny ‘flew into a passion, telling him he was some garreteer scribbler. Some poor hackney poet’. This commotion attracted Harris, ‘the negociator, who under pretence of snuffing the candles, had a mind to gain some intelligence concerning the cause of this tumult’. The doctor put his case, revealing both his ardor and his lack of ready money. Harris told the doctor that the young woman was ‘the celebrated Miss Fanny M—…who never went under two guineas’. The doctor, who could restrain himself no longer, handed Harris his silver-hilted sword ‘and asked him to have as much upon it as would satisfy the lady’. Harris, realising he could push the frustrated and lustful man further, stated that the sword would not pawn for above a guinea and a half, and demanded the fellow’s periwig as well. The doctor handed it over and the satisfied Harris then retired with his pledges, leaving his victim to come to more intimate terms with the ‘celebrated’ Fanny.

With their List Harris and Derrick had found a solid source of revenue and, it would seem, of pleasure. But the money – as well as the pleasure – came not just from the prostitutes, but also eventually their clients. Information was essential for the profitable functioning of the sex industry: clients had to know where to find prostitutes who, in turn, needed to make themselves and their whereabouts known to potential clients. At a stroke Harris’s List made life easier for all concerned. The initial plan seems to have been that clients would consult Harris for information in person – no doubt tipping him handsomely – but it was only a matter of time before the information was circulated in published form, with people paying to possess it at the rate of two shillings and sixpence per copy.34 Publication instantly made the List more readily available to many more people and thus, by making contacts between prostitutes and clients far easier, significantly increased the amount of money flowing into London’s sex industry, and ultimately into the pockets of men like Harris and Derrick.

The moment that Harris’s List went on public sale is suggested by a satirical little article that appeared in the Centinel on 2 June 1757. Describing prostitutes in the style of an advertisement for an auction of ships and their cargoes, the article implies that Harris’s ‘Pimp’s-list’ was available for purchase at three Covent Garden locations:

For Sale by the Candle At the Shakespeare’s Head Tavern Covent Garden: The Tartar and the Shark Privateers with their Cargo from Haddock’s, Harris, Master; Square stern’d Dutch Built, with new sails and rigging. They have been lately docked And refitted, and are reckoned prime sailors. Catalogues with An account of their Cargo may be had at Mrs D[ouglas]’s in The Piazza, or at the Place of Sale. To begin at twelve at night.35

The Shakespeare’s Head Tavern was a very near neighbour of the famed Haddock’s Bagnio, while Mother Douglas’ establishment was squeezed between them in a building on the north-east side of the Piazza.

By the 1770s Harris’s List had evolved into a regularly issued and updated publication on sale in a number of London establishments, and in the early 1780s was noted by Archenholz as one of the peculiarities of London:

A tavern keeper…prints every year an account of the women of the town, entitled, Harris’s List of Covent-Garden Ladies. In it, the most exact description is given of their names, their lodgings, their faces, their manners, their talents, and even their tricks…eight thousand copies are sold annually.36

In fact the List was not unique to London but spawned provincial imitations, notably Ranger’s Impartial List of the Ladies of Pleasure in Edinburgh. The Preface to the 1775 edition of the Edinburgh List offers a time-honoured and spirited apology for prostitution that attempted to raise its exponents to the status of national ornaments and muses:

Do they not sacrifice their health, their lives, nay their reputations, at the altars of love and benevolence…what villainies do they not prevent? What plots, what combinations do they not dissolve? Clasped in the delicious arms of beauty, the factious malcontent forgets the black workings of his soul…Though custom has loaded them with the infamous and ungenerous appellation of prostitutes, do we not owe to them, the peace of families, of cities, nay of kingdoms…were they hindered…think how terrible might the consequences be…wild frenzy breaking all restraint will bear down decency, relation, kindred and religion – What…litigation, bloodshed, incest!

The Edinburgh List gives little insight into Edinburgh’s centres of prostitution other than suggesting that the women of the town tended to be lodged in the tight closes off the High Street and Cannongate.

On the other hand, the editions of Harris’s List that Archenholz would have perused offer a fascinating vignette of London areas where the trade was conducted and reveal with extraordinary accuracy the disposition of the majority of the city’s middle-ranking prostitutes towards the end of the eighteenth century. The introduction to Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies: or Man of Pleasures Kalender for the Year 1788,37 makes it clear that Marylebone was ‘now the grand Paradise of Love’ alongside ‘Covent Garden, her elder sister’, and the addresses listed do indeed suggest that, at the time, the majority of prostitutes of the middle rank worked and lived in the more modest streets north of Oxford Street and west of Tottenham Court Road (essentially the Marylebone of the 1780s), and in Soho. For example, Miss Lister, 6 Union Street, Oxford Road; Miss Johnson, 17 Goodge Street, who the List noted had ‘such elasticity in her loins, that she can cast her lover to a pleasing height and receive him again with utmost dexterity’, and Miss Dunford ‘at a Sadlers, Charles Street, Soho’, who was…

…fond of music, plays with the greatest dexterity…full skilled in pricking, altho’ the principal part of her music is played in duets…she has not the smallest objection to two flats…she generally chooses the lowest part (and) sometimes plays the same tune over twice.

This mini-masterpiece of smutty innuendo duly advertised Miss Dunford as a bisexual available for lesbian (‘flats’) intrigues, among other things.

Sex and the London House

The houses occupied by the young women mentioned in Harris’s List were not, of course, purpose-designed for the sex industry, but were standard examples of speculatively built London domestic architecture. It had become standard practice for builders to acquire building leases from ground landlords, run up the shells of houses as quickly and cheaply as possible, and sell on the remainder of the lease and shell to the first occupant, who would then finish the interior of the house to suit their own taste and pocket. The advantages of the speculative system were that builders could make a fast profit by selling on the lease and shell for substantially more money then they had spent on the materials and labour of construction; the landlord got his ground developed for no expenditure and, although only receiving a small ground rent, his estate would, when the lease expired after 60, 80 or 99 years, gain possession of the houses; meanwhile the occupant was housed at a reasonable price. The potential disadvantages of the system were that corners were cut for the sake of profit and consequently vast areas of London were covered with tawdry and unsound constructions.

A series of Building Acts were passed after 1667, and throughout the eighteenth century in an attempt to ensure sound-and fire-resistant construction, and some estates attempted to apply building controls, but these generally had only minimal effects so that, by the mid-eighteenth century, many observers started to despair of the quality and solidity of London’s rapidly growing, speculatively built housing stock.

Isaac Ware, in his Complete Body of Architecture of 1756, fretted that:

The nature of tenures in London has introduced the art of building slightly [weakly]. The ground landlord is to come into possession at the end of a short term, and the builder, unless his Grace tye him down to articles, does not chuse to employ his money to [the landlord’s] advantage. It is for this reason we see houses built for sixty, seventy or the stoutest of this kind for ninety-nine years. They care they shall not stand longer than their time occasions, many to fall before it is expired; nay, some have carried the art of slight building so far, that their houses have fallen in before they were tenanted.38

The London art of ‘slight building’ became notorious. Jean-Pierre Grosely in his Tour of London of 1772 confirmed that ‘the solidity of the building is measured by the duration of the lease’ and that ‘the outside [of the houses] appears to be built of brick, but the walls consist only of a single row of bricks…made of the first earth that comes to hand, and only just warmed by the fire’ while James Peller Malcolm wrote in 1808 of ‘the horrid effect produced by the fall of frail houses’ and calculated ‘there are at this moment at least 3,000 houses in a dangerous state of ruin within London and Westminster’.39 But, if not notably sound in construction, the average London house was often beautifully and elegantly detailed and proportioned, and – of immense importance for a whole range of occupants, including those from the sex industry – it possessed a plan and form that was highly flexible and convenient, with staircase and landings serving as circulation space, allowing a large number of rooms to be accessed independently.

If not purpose-designed, many of the houses serving the sex industry would have been purpose-built, for large numbers were no doubt constructed as investments by bawds, pimps or successful prostitutes, using profits made from the sex industry, as was the case with Moll King. In addition, large numbers of houses would have been constructed by speculative builders who had sex-industry workers in mind as potential lessees, and many more would have been rented to prostitutes.

Archenholz observed the connection between London property and sex industries:

The uncertainty of receiving payments makes the house-keepers charge [prostitutes] double the common price for their lodgings. They hire by the week a first floor, and pay for it more than the owner gives for the whole premises, taxes included. Without these, thousands of houses would be empty, in the western parts of the town. In the parish of Mary-le-bone only, which is the largest and best peopled in the capital, thirty thousand ladies of pleasure reside [probably a misprint for ‘thirteen thousand’] of whom seventeen hundred are reckoned to be house-keepers. These live very well, and without ever being disturbed by the magistrates. They are indeed so much their own mistresses, that if a justice of the peace attempted to trouble them in their apartments, they might turn him out of doors; for they pay the same taxes as the other parishioners, they are consequently entitled to the same privileges.40

So in the late eighteenth century even superior prostitutes were notorious for the ‘uncertainty’ of their income and thus were insecure in their homes. They could be wealthy ‘kept’ women one moment, enjoying the income and lifestyle of their affluent and perhaps aristocratic protector, and then suddenly out of favour and, with no secure income, soon out of the house. This was, at best and even for high-class whores, a very insecure profession – which explains why a harlot’s dream was, as Archenholz explained, to secure ‘annuities paid them by their seducers’ or, more desperately, to obtain ‘other settlements into which they have surprised their lovers in the moment of intoxication’.41

Ivan Bloch, in his less-edited version of Archenholz’s text, gives more of the German visitor’s thoughts on this subject:

These annuities certainly secure them from need, but they are usually not sufficient to enable them to live sumptuously in the capital and to enjoy expensive pleasures; they therefore permit lovers’ visits, but only those whom they like – the others are sent away.42

The ability and willingness of certain prostitutes and their protectors to pay over the odds made them most attractive and valuable tenants. In Fanny Hill John Cleland describes how the heroine was set up by her lover Charles in a lodging in fashionable St James’s where ‘he paid half a guinea a week for two rooms and a closet on the second floor’. Cleland makes the point that this was a high rent. The landlord, observes Fanny, ‘had no reason to complain’ because Charles was ‘too liberal not to make him regret our loss’, and she thought the lodgings ‘ordinary enough, even at that price’.43 By comparison, the occasional harlot Bet Flint in the 1760s paid five shillings a week for her humble Soho furnished apartment, but even this rent was relatively expensive at a time when the average skilled London tradesman was earning between two shillings and sixpence and three shillings a day, and the going rate for a garret at the time was around one shilling a week.

Even if not particularly welcome tenants to some, prostitutes might be the only rent-payers a landlord could get. Pretty Doings in a Protestant Nation tells of ‘a fine young Creature, genteely dres’d, attended by a Woman four times her age’ who called at a house near Red-Lyon-Square looking for lodgings. The pair quibbled over details, including ‘the want of a Back-Door’, and an opposite row of houses were seen as a possibly ‘intolerable Inconvenience’ because the girl proclaimed that it was ‘Death to her to be overlook’d’, but she finally agreed to take an apartment. The landlady, who knew the business of her new tenant, was delighted to have ‘lett her first Floor to a Male and Female, to do the Work of Creation in without a Licence from the Clergy’, and added, ‘[H]ow should people be able to pay their Rent and Taxes if they were to be over-scrupulous in such Matters; especially, when half the Lodgings within the Bill of Mortality are fill’d with Coiners of false Love?’44

An erotic scene from a late-eighteenth-century edition of John Cleland’s Fanny Hill.

Discretion, gravity and a judicious level of display seem to have been the hallmarks and safeguards of a successful and independent prostitute working from her own lodgings. As Archenholz observed of well-to-do Marylebone-based prostitutes:

…their apartments are elegantly, and sometimes magnificently furnished; they keep several servants, and some have their own carriages…The testimony of these women, even of the lowest of them, is always received as evidence in the courts of justice [which, taken all together] gives them a certain dignity of conduct, which can scarcely be reconciled with their profession.45

Not all Marylebone sex establishments were discreet all the time; some, on occasion, made use of the most sexually charged detail of the common London house – the window. Throughout the eighteenth century it was usual for prostitutes to solicit from the windows of the houses from which they operated, and sometimes their displays could be most startling. Michael Ryan, in his Prostitution in London of 1839, felt obliged to resort to Latin to describe what some prostitutes got up to. Quoting J. B. Talbot of the London Society for the Protection of Young Females, Ryan explained that prostitutes ‘often exhibit themselves at the windows in the day time, in alluring positions; and in the evening or approach of dusk, in the more retired streets, variis modis corporibus nudis, saltant, ludant, et contant’, or as the historian Ivan Bloch translates it, ‘often stand naked at the window and execute all manner of indecent movements and postures’.46 This, stated Talbot, ‘was the custom at Madame Aubrey’s [in Seymour Place, Marylebone] and was complained of by the neighbours’.47 This tradition of sexual display made the house window a tender subject in Georgian London, to the extent that Archenholz observed in the 1780s that ‘to show oneself at the window is considered very improper. Nothing less than some street incident which may arouse curiosity can excuse an honourable woman from opening a window.’48 Quite simply, to peer through a window was, in many parts of town, tantamount to offering oneself to passers-by, for, as Bloch explained, ‘sitting at a window counted for a long time in England as a sign of prostitution’.49