Eleven

‘The Reception of the Distressed’

‘The Reception of the Distressed’

Hospitals and Workhouses

Georgian London possessed a small number of public or institutional buildings that were, in their different but related ways, significant architectural monuments to the city’s sex industry. Most have long been demolished and forgotten, and those that do survive are now generally no longer directly or immediately associated with the trade that brought them many of their users. These public buildings served various functions. There was the Foundling Hospital, which, to a degree and at least for a time, cared for the illegitimate and unwanted offspring of prostitution; there was the Magdalen House, which was a place of reception for prostitutes who wished to escape the sex industry and reform their way of life; and there were Lock Hospitals, which catered for those suffering from venereal disease and counted many poor prostitutes among their patients.

The best-remembered of these institutions is the Foundling Hospital, which from the mid-1740s was located in Bloomsbury until most of its buildings were demolished in 1928, but with some of its contents, collection and archives preserved in a new building adjoining the site of the old. The Foundling’s direct role in London’s sex industry remains controversial but many contemporary observers – informed and otherwise – assumed it was to a degree a refuge for babies born to prostitutes and so, tangentially, an encouragement to vice. By contrast, the link of the Magdalen House to London’s sex industry was never in doubt because it was founded in 1758 as a refuge for penitent prostitutes. The Magdalen had two physical manifestations in central London – first in Whitechapel, and then from 1769 south of the river near St George’s Fields – ultimately leaving virtually no trace after the institution, transformed in many of its aims, moved to Streatham in 1866.

But there is one reminder of it. Prescot Street – just north of the Tower of London – runs between Mansel and Leman Streets. In the mid-eighteenth century all three streets contained the large and handsome dwellings of wealthy City merchants and, along with Alie Street to the north, defined a large open space – the ‘Tenter Ground’ of Goodman’s Field – that had once been used for staking out washed and dyed fabric, wool and latterly silk, to let it dry in the sun without shrinking or warping by being restrained by tenter hooks. As well as being a quarter of wealth and industry, however, the area was also part of one of Georgian London’s more dubious centres of entertainment. There was a popular theatre in Alie Street – the Goodman’s Field Theatre – from at least 1727, and throughout the eighteenth century this part of Whitechapel was famed for the number of its often-outrageous bawdy-houses and prostitutes.

Now Prescot Street throbs to the sound of traffic all around it, with only a couple of Georgian houses surviving among much later and large-scale commercial and industrial buildings. But halfway down it, heading south into parallel Chamber Street, is a small, anonymous and generally overlooked byway. It is named Magdalen Passage and – marking the site of the long-gone Magdalen House – is the only physical memorial to the extraordinary experiment in moral, physical and spiritual re-education that took place here just over 250 years ago.

The Lock Hospitals have also all but disappeared from London’s memory, though in fact two of the most spectacular surviving institutional buildings of early-Georgian London – Guy’s Hospital in Southwark, founded in 1721, and St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Smithfield, with its stupendous quadrangle built during the 1730s to the designs of James Gibbs – both had connections to Lock Hospitals or incorporated Lock wards.

The Foundling Hospital

For the common prostitute in Georgian London there were few ways to avoid the most obviously evil and awkward consequences of her trade: sexually transmitted disease and pregnancy. There were many proclaimed preventatives and cures for both but most were based on varying degrees of ignorance, folk-lore and quackery – and many could end in death or irreparable physical and psychological damage. A variety of sexual techniques could be used to reduce the risks of both pregnancy and disease, and condoms made of sheep’s gut were available from the late seventeenth century but seem not to have been in general use among street prostitutes, presumably because they were too expensive or difficult to obtain. Also it was generally believed, no doubt by many prostitutes themselves, that precautions were not necessary because, as a pamphlet explained in 1752, a woman who ‘has to do with a Variety of Men upon the Back of another…cannot conceive, by reason she engrates various and opposite Qualities of Blood [and] by excessive Repetitions imbeciliates the feminary Parts, and renders the Act of none Effect’.1

Regular sexual activity with a ‘Variety of Men’ could indeed reduce a female’s fertility but due to venereal disease rather than to promiscuity in itself. No doubt many prostitutes were unhappily disabused of the veracity of this typical piece of eighteenth-century pseudo-science.

If a prostitute did become pregnant there were two immediate options – abortion or giving birth; and if a child was born then there were further options – to keep it (a huge and obvious difficulty and expense for a common prostitute) or abandon it, which often meant leaving the newborn infant to the mercy of the unloving parish authorities or even to take its chances on the street.

These stark choices did, of course, have many permutations. Unwanted infants could be ‘starved at nurse’ or ‘over-laid’, essentially slowly and carefully murdered to avoid an actual murder charge. The practice of slow death by neglect was a recognised evil attacked specifically by Dr Cadogan in his Essay on the Nursing and Management of Children of 1750, and referred to satirically in 1745 by Jonathan Swift in his Directions to Servants where he advises the nurse, ‘If you happen to let the Child fall, and lame it, be sure never to confess it; and if it dies, all is safe.’

Desperate or deranged mothers might attempt to sell their child into servitude, which could of course lead to its exploitation by the sex industry, or – mentally disordered by despair – would kill their infant, and perhaps themselves as well. The number of infants sold by their mothers – perhaps after some months of nurture – is now seemingly impossible to calculate but Peter Linebaugh, in his penetrating study The London Hanged, points out that between 1720 and 1750 12 per cent of the women hanged at Tyburn were executed for infanticide.2

The alarming sight of babies and young children abandoned in or roaming the streets of London shocked many observers, particularly when these infants were apparently not only products of, but also participants in, the capital’s sex industry. But although deeply dismayed, few observers seem to have formed any coherent plan either to tackle the cause of child abandonment or to deal effectively with its appalling consequences. The exception was Captain Thomas Coram.

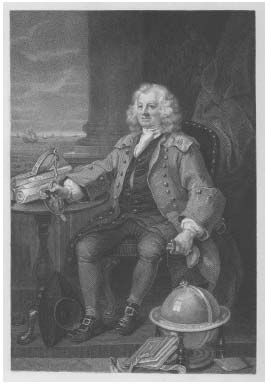

An engraving of Hogarth’s 1740 portrait of Thomas Coram. The painting was presented to the Foundling Hospital just as Coram was severing all relations with the great charity he had founded.

Biographies of him offer what is perhaps an apocryphal story. Coram, having worked and flourished in the American colonies and London as a sailing master, ship-builder and merchant, settled in the maritime quarter of Rotherhithe, on the south bank of the Thames. In the 1720s, while in his fifties and walking between Rotherhithe and the City, he ‘frequently saw infants exposed and deserted in the public streets’.3 Being of a charitable and enquiring turn of mind, the deeply troubled Coram looked into the cause of this horrible evil and ‘found that it arose out of a morbid morality, then possessing the public mind, by which an unhappy female, who fell a victim to the seductions and false promises of a designing man, was left to hopeless contumely, and irretrievable disgrace’.4 He became acquainted with the fact that a girl’s ‘first false step was her final doom’, for the ‘error of a day, she was punished with the infamy of years [and] was branded forever as a woman habitually lewd’. In such a situation the girl, ‘seeing no…means of saving her character’, became ‘delirious in her despair’ and either murdered or abandoned ‘the child of her seducer’.

This was the tale as told in the mid-nineteenth century5 and what is significant, of course, is that there is no mention in it of prostitution. The children that Coram saw and wanted to save were not, according to this account, the abandoned spawn of prostitutes, but of ‘delirious’ and despairing young women who, far from being loose women, were the otherwise virtuous victims of ‘false’ young men, with their offspring being the error of an ill-fated single ‘day’.

Sustaining this singular and unlikely claim for the origin of the Foundling’s stock of babes became something of an obsession for a hospital that was, from time to time, accused of encouraging and abetting vice by providing a haven not only for illegitimate children of the victims of seduction but also for children born to habitual and hardened prostitutes. But in the early days of the hospital’s gestation the implication of its aims for the morals of London seems not to have been a major concern among its supporters even though Coram had, from the very start, to contend with arguments that such an institution would merely ‘increase illegitimacy and encourage vice’.6 He complained to a friend that ‘many weak persons, more Ladies than Gentlemen, say such a foundation will be a promotion of wickedness’, but for him this was a peripheral issue.7 Far more important was the mission to save wronged unmarried mothers from ‘disgrace’, and to provide unwanted ‘young children’ with a purchase on life and the possibility of a secure and productive future.

But it seems gradually to have become clear to many involved in this project that its aims – bold and admirable as they were – did in fact lead them into a moral minefield. Indeed, even the reasons stated for saving the lives of abandoned infants were extraordinarily complex. Of course such an action was humane and befitted a Christian nation, but it also had to do with matters of nationalism, patriotism and hard economics. The traveller, merchant and philanthropist Jonas Hanway – who was to become one of the Guardians and Governors of the Foundling – revealed why the lives of all infants were important for the welfare and prosperity of the nation. In the mid-eighteenth century there was general fear of a depopulation of Britain that would, it was assumed, ultimately lead to failure in competition with other nations. This was a fear that could not be scientifically answered because no reliable national census was even attempted in Britain until the Census Act was passed 1800, leading to the first full census within the British Isles since the Domesday Book.

Hanway observed in 1759 that ‘there are many people in this nation who entertain an opinion, that we are decreased in number, since the year 1714, above a million’,8 though he was not convinced this was the case: ‘Liberty and plenty’ – the virtues he associated with England – ‘should naturally create an increase of people’. But he owned that there was some worrying evidence to support the depopulation alarmists.

Gin and tea [the latter an irrational pet hate of Hanway’s]…indeed have swept off thousands, and gin in particular has prevented many thousands more being born. War has swept off some; the Great Neglect of marriage has prevented increase, many living single who ought to marry…Venereal diseases have carried off many…whilst the carelessness of nurses has swept off numbers of infants.

Hanway failed to mention the popular assumption that colonial expansion was emptying Britain, though he did give it as his opinion that a great cause of the ‘prevention of increase’ in population was the murderous condition of parish workhouses.9 So the lives of all British babies – no matter what their station in life, the circumstances of their birth or the actions of their parents – were precious for the contribution they could potentially make to the common good.

Meanwhile Coram, brooding over the terrible sights that confronted him daily in London’s streets, conceived a humanitarian mission that would not only save and give purpose to otherwise wasted lives but also make a contribution to the prosperity, power and welfare of the nation. For years he investigated, lobbied and discussed the possibility and means of establishing some sort of institution or, to use the generic eighteenth-century term for such establishments, ‘an hospital’ for abandoned children. Gradually he built up the support of a large number of people of power, wealth and influence – each moved by many or most of the issues such a project embraced – and on 17 October 1739 obtained a Royal Charter.

The name of the institute and its aims initially seem straightforward but are laden with moral and ethical implications and potential contradictions, revealing how complex such a seemingly simple aim as saving children’s lives could be in mid-eighteenth-century Britain. The charter announced that the institution was to be called ‘The Foundling Hospital’ and that it was to be ‘for the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children’. But from the start the hospital was evidently not to be specifically for foundlings – that is, abandoned children ‘deserted and exposed’ – but for those brought in for disposal by their parents or others, possibly even children of legitimate birth whose parents happened to find it too inconvenient, awkward or expensive to maintain them. By whom and using what criteria were babes to be chosen? How were adequate funds to be obtained and cash flow maintained? And how ‘young’ exactly did a child need to be to make it eligible for acceptance?

Incredible as it may now seem, these tricky issues were not fully or satisfactorily resolved at this key initial stage, with only a basic and flimsy set of operational criteria agreed. Perhaps Coram and his closest supporters realised that any such resolution was impossible and that the whole enterprise could founder if its mechanism were too closely picked over, or least suffer interminable delay. The first general meeting of the Foundling Hospital was held at Somerset House on 20 November 1739, during which the Duke of Bedford was chosen as President and the ‘nobility and gentry’ announced who were stipulated by the charter to act as ‘Governors and Guardians’ of the Hospital. A General Committee of fifty was selected by ballot, which included such eminent men as Sir Hans Sloane, founder of the British Museum, and the Rt. Hon. Arthur Onslow, afterwards Speaker of the House of Commons.10

During this event Coram addressed the audience and announced that the ‘Hospital for exposed children’ would operate free of all public expense ‘through the assistance of some compassionate great ladies, and other good persons’.11 This was a bold claim that he surely knew would be hard to sustain. He also added to the cloud of confusion surrounding both the aims of the hospital and the conception and births of the babies it was established to save when he declared that ‘the long and melancholy experience of this nation has too demonstrably shewn, with what barbarity tender infants have been exposed and destroyed, for want of proper means of preventing disgrace, and succouring the necessities of their parents’.12

Fear of ‘disgrace’ on the part of seduced and unmarried mothers may have been one reason – even a major one – why babies were abandoned on the streets of London. Coram must have known that there were many others, but to blame such abandonment on the shame of a duped girl made the Foundling’s efforts to save the babes less provocative and more attractive to potential financial backers than admitting that many such abandoned babes were the direct result of prostitution. If this were publicly acknowledged then what the hospital proposed doing was, it could be argued, no more than making the immoral lives of prostitutes ethically easier and therefore more attractive.

From what was perhaps a pragmatic assessment of the type of charity work that would best attract sponsors, combined with a certain moralistic dogmatism, the Foundling forged its first admission policy and refined its aim. It made it clear that it did not want to aid prostitutes by taking their unwanted children and, far more confusingly, also made it clear that it did not actually want to offer refuge to all abandoned babes – as Coram himself did. Rather, as Randolph Trumbach points out, its primary aim was to ‘maintain the reputation of an unmarried mother and allow her to return to work’.13 To achieve this aim the hospital announced that ‘petitioners’ – as women bringing babies were called – were more likely be successful if they could demonstrate that they had kept the disgrace of their illicit pregnancy a secret as long as possible, so that their reintegration into conventional society could be painless and speedy.

So, as it launched itself upon the world, the Foundling had two aims: the one proclaimed in its charter – to maintain and educate ‘exposed and deserted young children’ – and the one expressed in its policy – to save unmarried mothers from ‘disgrace’. The former was to do with the preservation of human life and dignity; the latter with the preservation of reputation and social standing. That these aims were not necessarily compatible, indeed that they could be contradictory or even mutually exclusive, seems to have been overlooked. If a mother’s disgrace was public and absolute and her social rehabilitation unlikely, perhaps due to no fault of her own, was her baby automatically to be rejected by the hospital and perhaps condemned to death or years of miserable existence – also through no fault of its own? It seems the moral dilemma inherent in potentially conflicting aims was not foreseen – certainly not by the public at large or, apparently, by most of the people Coram approached for aid.

The list in the Foundling’s Charter of those lending support to the new hospital remains incredibly impressive – both for the quantity of the names it contains and their influence and diversity. Coram had enlisted the aid not just of the great and the good but also a wide cross-section of London society. Alongside the names of powerful aristocrats were those of artists such as William Hogarth, to be joined later by George Frederic Handel. The Foundling Hospital project had clearly captured the imagination and emotions of the capital, and the immense support it received – at least initially – confirmed the depth of concern that many must have felt, for a long period, over the numbers of babes exposed and young children lawlessly roaming the streets of London.

Subscriptions from the initial supporters brought in enough funds to set the hospital in motion even before a purpose-designed building for its operations was built. There was, quite understandably, an air of urgency about the whole scheme. The methods employed by similar long-established institutions on the continent were studied so as to establish the rules and routine of the Foundling. Premises were acquired in Hatton Garden near the highly disreputable sex trade area around Saffron Hill, Hogarth designed a shield-like ‘trade sign’ for the establishment, and its doors were opened for business.

From the beginning, however, things started to go wrong, revealing in dramatic fashion how poorly the functioning of the hospital had been planned. In March 1741 a notice was posted in Hatton Garden announcing the start of operations: ‘To-morrow at eight o’clock in the evening this house will be opened for the reception of twenty children.’ The ‘regulations’ governing consideration for admission were also listed. No child over two months old would be accepted, ‘nor such as have the evil, leprosy, or disease of the like nature whereby the health of other children may be endangered’. Those bringing children were told to ‘ring a bell’ on the outward door and wait until the fate of the child was decided, and they were assured that ‘no questions whatever will be asked of any person who brings a child’. It was also requested that all people who brought babies ‘affix on each child some particular writing or other distinguishing mark or token, so that the children may be known hereafter if necessary’.14 This regulation, which was intended to allow mothers to identify their children if required at a later date, led to the creation of a truly poignant archive of objects, some of which remain in the hospital’s possession while others are lodged in fragile eighteenth-century volumes now in the London Metropolitan Archives.

These tokens and notes are pinned in the ‘Billet Books’ that record each child’s acceptance, together with information compiled on a standard form giving date and time of admission, allocating the child an identifying letter of the alphabet, and recording its sex, age and ‘Marks on the Body’. Any objects or texts that came with the baby were also noted against a standard list including, ‘Cap, Biggin, Forehead-Cloth, Bibb, Petticoat, Mantle, Sleeves, Blanket, Waistcoat, Shirt, Clout, Stockings…’ Sometimes the mother left a name. One form, dated ‘Hatton-Garden December 9th 1743 at 61/4 o’Clock’, recording the admission of a baby boy has a scrap of paper pinned to it that, the form records, was origin ally pinned to the child’s breast. It simply reads: ‘Charles Talbot born 22 November 1743’.

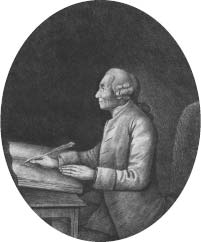

A later engraving of Hogarth’s emblematic picture made for the Foundling Hospital, showing, in the centre, Coram holding the founding charter with a mother kneeling before him. She has dropped the dagger with which she would have killed her baby or herself. In the left background, a child is being abandoned in the night. On the right the foundling children are being brought up to follow useful trades, such as spinning.

Occasionally attached to the forms is a token. For example, in the volume covering admissions from late 1743 to late 1745 to Hatton Garden and Bloomsbury,15 a female baby aged three weeks is recorded as having arrived at ‘Lamb’s Conduit fields’ on 15 November 1745 at 7 o’clock, and to the form is pinned the cut-off end of a woman’s sleeve, described on the form as ‘Blue & White Stryp’d Cotton…and white Linnen’ and a ‘narrow pink Ribbon’. Another page – recording the arrival of a two-month-old boy – has pinned to it a white cotton open-fingered mitten or sleeve end with silk trim. These items were, in later life, the only things the child had to give it any sense of identity – the only physical connection to its mother.

From the moment the doors of the Foundling Hospital first opened in Hatton Garden far more babies were offered than could be accepted, and unfortunately no one had foreseen to what extremes desperate mothers would go to deposit their child in a place of safety. There were riots outside the door as women struggled for places at the head of the queue. The hospital authorities were aghast. They could only accept the limited number of children that their funds – determined by subscriptions or legacies – permitted so the only way to reduce this unseemly scramble was to devise another system of admission. Soon one was found, and was almost equally bizarre as the scramble for places because it made the acceptance of children a mere lottery, with little allowance for particular circumstances.

All the women who arrived on admission day were brought inside and selected a ball from a bag. The balls were of three colours and their number and ratio based on the number of children being offered on the particular day of selection. If the woman selected a white ball she was moved to the ‘Inspection Room’ and her story and child examined; if she selected a black ball she was turned out with the assurance that she could try her luck another day; and if she selected a red ball, she stood by to take the place of any white ball holder whose ‘petition’ was rejected, perhaps simply because her child was the wrong sex, since the aim was, if possible, to select an equal number of boys and girls.

This system of admission was clearly morally and ethically dubious and open to all manner of abuse and bribery. Coram himself was alarmed and felt that the basic proposition of his charity – that all eligible children be accepted without the need for any tests – was already being undermined. By these methods 136 children were admitted in the first year, the annual average soon being established at just under 100, with 821 children being admitted by 1751, of whom 316 had soon died.

Despite concerns about this system of admission it continued until May 1756 by which time 1,384 children had been received.16 Jonas Hanway, a Governor and Guardian of the Hospital, described this early phase of admission, notably the fate suffered by these pioneer infants: ‘Thirty children were put out to nurse, and soon another thirty more, and in the course of the year one hundred and thirty-six.’ The phrase ‘put out to nurse’ means that the babies were put into the care of a number of wet-nurses, whose time or abilities seem to have been limited since, as Hanway records, of this 136 babies, apparently healthy when admitted, 66 soon died. This mortality rate of nearly 50 per cent didn’t appear to worry Hanway, who merely observed that it was ‘not many more than the ordinary proportion which usually die in the course of births’ among children in towns, while of the 1,384 received by May 1756 ‘only [sic] 724 died…at once exhibiting a proof of the great care and tenderness of the Governors of that time’.17

During the early part of 1742 the Governors focused their attention on acquiring suitable land and procuring a design for their hospital. Indeed the first item on the agenda for the first meeting of the Court of Governors, held on 29 November 1739 at the Crown and Anchor on the Strand, had been the question of premises. Various possibilities were considered, including the offer by the Duke of Montagu of a twenty-year lease, at £400 per annum, on Montagu House. This offer was not taken up and the rambling late-seventeenth-century building was eventually taken over as the first home of the British Museum. The Governors had their hearts set on commissioning a purpose-designed hospital that provided exactly the accommodation needed for its very specific function and which would be set among greenery and in fresh air on the edge of the city. The site of the rejected Montagu House had in fact been ideal – located on the north side of Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury, its garden ran into open countryside – and so the Governors searched for land on the north-west edge of central London.

A committee meeting of 17 October 1740 discussed a recommendation to purchase two fields at the northern end of Lamb’s Conduit Street – a major thoroughfare running north from Holborn and Theobalds Road. The landowner was the Earl of Salisbury, who drove a hard bargain, demanding £500 more than the £6,500 the hospital was prepared to offer. But all was amicably settled when the Governors agreed to purchase 56 acres for the asking price of £7,000, with the earl himself making a £500 ‘contribution’ to the purchase of his own land. Honour was satisfied on both sides.

Several architects were then asked to prepare designs for the hospital, with those drawn up by amateur architect and City merchant Theodore Jacobsen – who most attractively declared his intention to waive a fee – being approved on 20 June 1742. Jacobsen had some experience in the design of institutional buildings – notably premises for the East India Company in the City – and worked in a spare classical style that was at once economical, visually simple and physically robust. This was a winning combination that struck just the right note for the hospital, which wanted its building to be solid, solemn and dignified without being showy and apparently the recipient of vast sums that might otherwise have gone directly towards the maintenance and education of ‘young children’. Jacobsen achieved dignity and solidity on the cheap by using brick throughout rather than large quantities of expensive stone and, instead of trying to make an impact by utilising such showy details as giant columns, relied for visual effect on beautifully crafted brick details, strong geometrical composition and generous proportions.

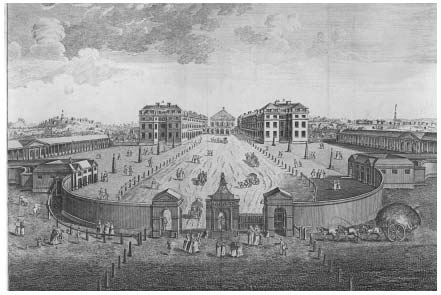

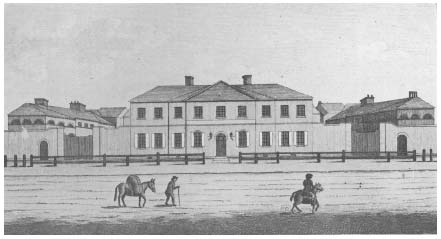

The Foundling Hospital, looking north, when completed in the early 1750s.

The hospital, when finally completed in 1752, was in many ways a modest masterpiece of mid-Georgian institutional architecture. Its layout was based on the well-established collegiate form favoured earlier by almshouses, medical hospitals such as Guy’s and other comparable structures. The public and state portions of the building – notably its chapel – occupied a central block, framed and flanked by wings dedicated to more humdrum areas such as residential wards and that advanced forward to define an entrance court. Visual variety was lent to a potentially repetitive and barracks-like composition by the most minimal of means, with walls breaking forward to suggest corner pavilions and bold details – such as arcades, semi-circular windows and simple brick pediments – being used to give grandeur, emphasis and interest.

But perhaps most importantly the hospital was fully detached, set in a park-like garden defined by walls and low colonnaded utilitarian structures, and thus removed from the nearby terraces of smoke-belching houses. In its splendid isolation the new Founding Hospital made its mark as a significant public building while also enjoying fresh country air, unrestricted light, and fine prospects across the open countryside to the north and west. This, the Governors rightly believed, was the environment essential to help safeguard the health of the hospital’s infant population as well as the right sort of architecture to proclaim the dignity and serious intent of the institution.

Another advantage of Jacobsen’s design was that its construction was easy to phase, allowing the complex to be completed gradually as money became available. The foundation stone was laid on 16 September 1742, with the west residential wing being completed first and inhabited in October 1745; after that the chapel range was built, and then in 1749 the east wing was started. But by the time construction started, Thomas Coram’s involvement in the affair of the hospital that bore his name was at an end. In 1742, when the location and design of the Foundling’s new building were being agreed, something extraordinary happened that has never been fully explained. Thomas Coram and the governing body of the institution he had founded became speedily and dramatically estranged.

The root of the separation may have lain in Coram’s disagreement with the manner in which babies were selected for admission, but the surviving evidence suggests that, even if this were the case, there were other issues as well. Probably the rift stemmed from a variety of disagreements, reflecting the unresolved and potentially conflicting nature of the Foundling’s aims and fundamental differences of opinion over the way in which the institution was being managed. Certainly the row soon became intensely personal and bitter. Its nature and intensity tend to confirm the essentially dysfunctional, almost fanatical, nature of the organisation in its early years.

Coram’s disagreements with a number of his fellow Governors started during 1741 and reached crisis point in October when damaging rumours of irregularities within the hospital were circulated. If left unchallenged these rumours threatened to harm the institution’s fund-raising and very future and so a sub-committee was speedily appointed to investigate. It focused on stories, spread by nurses, about two members of the hospital’s committee and suggestions that the head nurse was immodest, dishonest and drunken. After due investigation the sub-committee deemed these rumours to be ‘untrue and malicious’ and, to express its deep displeasure, decided to apportion blame in a most public manner by stating its belief that ‘Mr Thomas Coram, one of the Governors of the Hospital, had been principally concerned in promoting and spreading the same aspersions’.18 Coram and his colleague Dr Nesbitt, also associated with the circulation of the rumours, ‘were not censured, but evidently came under the severe displeasure of their colleagues, and their positions probably became untenable’.19 The nurse, despite her official clearance, was discharged the following month – suggesting that not all the rumours were entirely unfounded – while Coram’s official connection with his great creation came to a sudden and spectacular end.

He was seventy-three, famed as a great philanthropist with his recently painted portrait by Hogarth just hung in the hospital…but he was out. It seems that, for whatever reason, he had become involved in a nasty struggle for power and influence in the hospital that was suddenly a grand, high-profile and fashionable establishment, and he, essentially a home-spun and humble sea captain, had lost.

The precise details of the rumours, the investigation and Coram’s role are now unknown because the facts were, according to R. H. Nichols and F. A. Wray’s 1935 History of the Foundling Hospital, ‘contained in a sealed dossier which disappeared in about the middle of the last century’.20 Coram attended a committee meeting on 5 May 1742, but it was his last. Later in the month he failed to be re-elected to the General Committee of Management. Rather sadly, in his last vote as a committee member he was against the otherwise unanimous resolution approving the purchase of 400,000 bricks for the construction of the new building. Evidently his disenchantment with the project was by now so great he didn’t actually want to see the hospital built.

But Coram – disappointed, disillusioned, powerless and increasingly impoverished (a distress from which the hospital would eventually and generously help to rescue him) – could do nothing now but watch his creation rise from the fields; and as it did so its Governors become embroiled in a moral maze of controversy and uncertainty that led – some years after Coram’s death in 1751 – to near-terminal catastrophe. The completion of the building provoked admiration but also the sort of observations and criticism that Coram had done his best to deflect by implying that the hospital was primarily for the children of duped and deluded unmarried mothers rather than for those of professional harlots.

For example, in 1752 there appeared a sardonic satire entitled A Particular but Melancholy Account of the Great Hardships, Difficulties and Miseries, that those Unhappy and Much-to-be-pitied Creatures, the Common Women of the Town, are Plung’d into at this Juncture, written by John Campbell under the name of M. Ludovicus.

Campbell observed in his mischievous pamphlet:

There has been within these few Years, so many fine Structures built for the Reception of the distressed…witness the most excellent, well-endow’d, and well-designed Structure for the Encouragement of Whoring, to wit, the Foundling Hospital, where many a fine Merry-begotten is well provided for [where] sometimes their Pappas and Mammas come incog. in their Chariots to visit the Product of their dark (but sweet) Performances; stolen Waters are sweet, and Bread eaten in secret is pleasant; I think it would not be amiss to build a gay House for the Reception of all the poor Mothers, Sisters and Aunts of these hopeful children…for their Support, seeing…such fertile trees…have produced such excellent Fruit for the Benefit of the Nation.21

This notion of the Foundling as a convenient refuge for the illegitimate children of high courtesans and their gentlemen clients was precisely what Coram had been anxious to avoid lest it should discourage donations, but this was too tempting and titillating an issue to be overlooked. In the same year, the 23 June issue of Henry Fielding’s Covent Garden Journal (No. 50) carried a letter, signed Humphry Meanwell, that questioned the purpose and organisation of the hospital and concluded by asking Fielding,[O]f what Service is an Hospital for Foundlings on this Supposition; are none but the Bastards of our Great-ones to have the Benefit of it?’22

It is now impossible to say how widespread such observations were, how seriously people believed the hospital was little more than a repository for harlots’ offspring, and whether such gossip or suspicions undermined fund-raising. What is certain is that such negative observations were accompanied, and presumably balanced, by the sort of promotional sentiment included in a popular print of the hospital published in April 1749 by Grignion & Rooker. This shows women arriving with babies and instructs the viewer to:

See where the Pious Guardians publick care

Protects the Babes and calms the Mothers Fear

Inspired by Bounty, raises blest Retreats

Which…Charity compleats.

It is also clear that the hospital, presiding in its large new building, was finding it hard to raise the sums of money needed to fulfil its mission. Fund-raising events helped, such as a charity performance organised by Handel in 1749 when over 1,000 people paid half a guinea each to hear a performance of ‘the Fire Work music and Anthem of the Peace, oratorio of Solomon and several pieces composed for the occasion’. Such was the success of the event that every year until his death in 1759 Handel supervised a performance of the Messiah in the chapel, earning the hospital around £7,000 in total. But still it was not enough. The Governors needed far more money to run the hospital and expand its operations than promised by their income, donations and fund-raising if the ambitious founding aim of receiving, educating and apprenticing out all eligible ‘young children’ was to be achieved.

They were getting increasingly desperate, even considering granting building leases for the development of the hospital’s land. Its buildings and surrounding gardens occupied twenty acres, leaving thirty-six available for construction, but the early 1750s was not a good time for speculative building since markets were depressed by political and economic uncertainty caused by the deeply unsettling Stuart rebellion of 1745 and the imminence of war with France. So no serious development proposals were drawn up, which was probably just as well. Such a scheme could have split the Foundling’s governing body, with many Governors no doubt opposing a move that would have done much to rob the hospital of the healthy pleasures of its bucolic location.

Instead the Governors decided to petition Government for financial aid. In April 1756 the House of Commons agreed to ‘provide the hospital with liberal grants of money’, starting with £10,000, providing it consented to accept all eligible ‘exposed and deserted young children’ from all over the country at ages settled upon by the Governors and the Government. This open admission policy superficially suited the hospital’s general aim to help all abandoned and unwanted babes, but as events quickly revealed, neither Governors nor Government had given any deep thought to the full implications of transforming the Foundling into a nationwide and semi-public institution, almost at the drop of a hat, with little long-term planning or provision.

Despite good intentions all around, things quickly went wrong for, as Jonas Hanway wrote sadly in 1759, ‘every hour gives proof of the fallacy of human wisdom’.23 An advertisement announced the start of the open admission scheme at 6 a.m. on 2 June 1756 when a basket was hung at the hospital gate on Guilford Street. Now all children not exceeding two months old would be received, with the depositor needing to do no more than place the baby in the basket, ring for the porter and make off. At a stroke, the hospital had abandoned its carefully constructed and painfully sustained argument that it was not primarily a refuge for harlots’ babies – and so an encouragement to vice – but for those of modest but duped wenches. It also abandoned its policy of accepting only healthy children.

Instantly the floodgates opened. Within the first twenty-four hours the Foundling was floundering. As Hanway recalled, ‘I well remember the transaction of the first general taking-in-day, the 2d June, when we received 117 children. This whole month produced 425, all of them supposed not to be above two months old…’24 What happened to deposited babies who were obviously over two months old has never fully been explained.

The Foundling was simply not prepared for such numbers, nor was it prepared for the strange and dark forces it had unleashed. Hanway explained, ‘Nobody conceived it would become a traffic to bring children…nor did we dream that parish officers in the country would act so unlike men, as to force a child from a woman’s breast’.25 What happened, with extraordinary speed, was the development of a trade in children in which impoverished parents in distant parts of the land paid carriers to take their unwanted children to the Foundling. Many babies failed to arrive at all if the carrier chose to avoid the trouble of the journey by simply murdering or abandoning their helpless charge. And even when children did complete the journey, many arrived in states of terminal decline. To add to this horror, parish officers around the country quickly realised they could get destitute orphans or the children of poor parents off their hands by delivering them to the Foundling so that the Government rather than the parish should pay for their upkeep. Some officers, as Hanway recorded, even virtually abducted and dispatched the children of helpless poor women so that they would not be a future charge on the parish.

The consequences of this combination of unfortunate circumstances were appalling. In the first year of indiscriminate admission the number of babies received of two months’ age or less was a staggering 3,296, many of them squeezed into a building designed to house only around 600, of varied ages, in its series of wards.26 In the second year 4,085 infants were admitted, and in the third 4,229.27 Various rural outstations had been established but, as the mid-nineteenth-century historian John Brownlow observed, the Foundling now embraced a ‘system void of all order and discretion’ and ‘instead of being a protection to the living, the institution became…a charnel-house for the dead!’28 Between 2 June and the end of December 1756 1,783 children were admitted, all supposedly under two months old and, as Nichols and Wray observed in 1935, ‘it is difficult to comprehend how they were dealt with at all by the small staff available’.29 Also a great number were received in states of neglect and ill health that made their death almost inevitable.

The hospital’s Billet Books from this time of unrestricted admission are unlike the earlier volumes because, with dramatic directness, they reflect the desperate haste of the moment. On standard forms information about babies received is reduced to the minimum, with no mention of age, just sex, and no requirement to leave a token. But to judge from elsewhere in the Billet Books, and from collections of papers in the London Metropolitan Archive, those depositing babies still often pinned upon them scraps of paper informing the hospital of the child’s name, parish or place of origin, and whether it had been baptised or not. These scraps were duly noted in the Billet Book and carefully pinned to the form recording the baby’s details. And occasionally tokens were left. Some of the papers deposited with the babies contained explanations, enigmatic descriptions, even poems. For example, baby number 5312, admitted on 2 August 1757, carried with it the verse:

Here I am brought without a name

Im’ sent to hide my mother’s shame,

I hope youll say, Im’ not to Blame,

Itt seems my mothers’s twenty five,

And mattrymonys Laid a side…30

The note with baby 8575 admitted on 17 May 1758 states plainly that ‘This child is the son of a Gentleman & a Young Lady of fashion’,31 which was as near as it was decent to get to an admission that the infant was the result of prostitution.

The Billet Book covering admissions in October 175632 includes with the entry for child 2584 a token described as ‘silk with Fringe and paper’. It’s a beautiful fragment of what appears to be Spitalfields silk, presumably part of a fine dress worn by the mother. The piece of folded paper to which the silk is pinned is now too delicate to open easily, but glimpsed inside can be seen the word ‘…Square’. The form to which the token is attached states ‘Female, Hanover Square not christened’. So it seems the mother not only could afford to wear an expensive silk dress but came from a most superior parish. Who – and what – could she have been?

The anguish of some of the mothers is captured in a bundle of letters that survive from this period when babies were deposited anonymously into the hands of unknown strangers – via basket and bell – with no ritual of farewell. One letter dated 28 July 1758, and presumably left in the basket with the baby, reads:

I am sorry that necessity obliges me to part with my child as ye Father is abroad but hope that when he returns it will be in my power one day to make you satisfaction…the child is half baptized its name is Mary, was born July 26 1758 at ye Parish of St Andrews, Pray God bless and preserve it for some good purpose to ye Glory of its maker, Amen.

Another scrap of now crumbling paper, with two fragments of printed cotton pinned to it, merely pleads, ‘Please take care of this child – it will be called…’ and then decay obscures the rest, but overleaf is more information: ‘…about 17th July 1756, Eliz. James…with a white & gold Ribbon round the Waste…’ The content of this short, incomplete but unspeakably poignant message, combined with the decay of the paper on which it is written and the faded but once gay and colourful cotton, is heartbreaking. It lends immediacy to a distant tragedy and is a vivid reminder of the agony that took place on a daily basis at the gates of the Foundling as despairing mothers gave their babies away.33

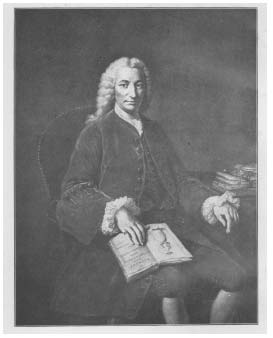

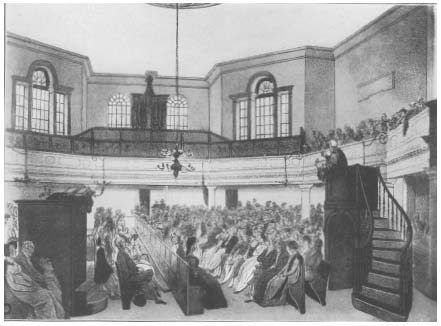

Children being received into the hospital in 1749 by the system of ballot. Mothers who selected a white ball had their ‘petition’ chosen for examination. Those who selected black balls were immediately rejected.

The shocking events that were unfolding at the hospital with alarming speed did not stop this ghastly experiment in its tracks. Instead things grew worse as the Governors tried to find a way out of the nightmare that had suddenly engulfed them by asking the Government for more money. As early as December 1756 they pleaded for an increase in their grant, but extra cash came at a price. More money was only justified, argued the Government, if more children were eligible for admission, so the age of entry was extended to six months or less. It was a vicious circle in which the solution to one problem created another. The whole place was overtaken by chaos.

Hanway records that in the 18 months from 2 June 1756 to the end of December 1757, 5,618 children were received into the hospital of whom 2,311, or 41 per cent, died. During 1757 yet more money had been needed from the Government and so yet again the age of admission was extended with, after June 1757, all children of twelve months of age or less being eligible. And so the terrible system lurched on until late 1759 by which time 14,934 children had been received in 46 months of unrestricted admission, meaning that nearly 100 children were admitted a week – which until June 1756 had been the total number of annual admissions!34 Of the 14,934 children admitted ‘only 4,400 lived to be apprenticed out,’ according to Brownlow, ‘being a mortality of more than seventy per cent!’35 ‘Thus was the institution,’ he concluded, ‘conducted on a plan so wild and chimerical, and so widely differing from its original design, found to be diseased in its very vitals’, with the system ‘contemplated by its Founder…set aside by a system of fraud and abuse, which entailed on the public an immense annual expenditure, to establish a market for vice to carry on her profligate trade without let or hindrance’, and which permitted ‘designing persons’ to ‘dispose of children entrusted to their guardianship [without] discovery of their guilty acts’.36

Nichols and Wray’s more restrained official history of the hospital cannot but, in essence, agree. They calculate the slightly higher survival rate of 4,54537 but admit that ‘the place took on more the appearance of a mortuary than a sanctuary…with a mortality of over 70 per cent in a period under four years’.38

Brownlow, Nichols and Wray were writing with the benefit of hindsight but even by early 1759 it had become clear to many that the events taking place at the Foundling were starting to assume the dimensions of a national scandal. The committee struggled to find solutions and to understand exactly what was happening. On 21 February 1759 it received a report that of the 210 children admitted during the previous week, 65 had died. A further 93 were to die the following week, making a total of 158 or nearly 75 per cent. In the week ending 3 March 1759, 211 children were received and 183 died.39 Clearly the hospital and the scheme it was operating were fatally out of control and a serious danger to children.

In May 1759 the Government observed that the ‘evil consequences’ of ‘conveying the Children from the country to the Hospital…ought to be prevented’ and rescinded its general resolution of 1756, which meant that the whole arrangement was reconsidered. In December 1759 it asked the hospital for information on the number of children admitted between 31 December 1758 and the end of September 1759 and how many of them had subsequently died. The hospital duly reported that during the period in question the total number of children on its books was 6,223, including 1,469 children recently admitted, and that 2,264 had died.40 So, by one analysis, more children were dying in the hospital over a given period than were actually being admitted. As Nicholas and Wray observe, ‘it became obvious that it was impossible to continue the system of indiscriminate admission’, because it not only ‘lent itself to many forms of abuse’ and was partly the cause of the shockingly high death rate among the hospital’s young inmates but also ‘public opinion turned against it’, since it was now generally believed ‘that the unlimited facilities provided for disposing of illegitimate children were encouraging prostitution’.41

By late 1759 the Foundling Hospital was discredited, seen not only as grossly incompetent but also, in the persons of some of its staff and Guardians, as possibly corrupt. In February 1760 the Government ruled that the general admission of children must cease, and terminated its relationship with the hospital. By that time the Government had spent the huge sum of £500,000 of public money on what had amounted to a massacre of the innocents. There were 6,293 children on the hospital’s books when the resolution was passed – many housed in outstations in Shrewsbury, Aylesbury and Yorkshire – of whom the majority were under five years of age. Since each one cost about £6 a year to maintain, the hospital was plunged back into financial crisis.42

Although the Government terminated its ongoing relationship with the hospital it continued to pay out sums to maintain the children taken on during the 46 months of madness. These fluctuated and decreased as children eligible for Government aid died or were gradually apprenticed out of the hospital, with the last payment made in May 1771 when the Government declared that ‘no further sum or sums of money be hereafter issued for the Maintenance and Education of such children as were received into the said Hospital on or before the said 25th March 1760’. By this time the Government had over the course of sixteen years paid the hospital £549,796.43

At the same time as the Government withdrew its support, public donations dwindled when the full extent of the chaos at the hospital became known. The Foundling was now desperately worried about its funds and most anxious to regain its former reputation and level of public support. But its cause was not helped by the decision it had made on 30 June 1756 – when first rattled by the unexpectedly large number of children delivered to its doors and the escalating costs – that any child ‘brought to the Hospital…exceeding the Age of two Months and…under the Age of two Years’ who was accompanied by ‘a Sum of one hundred Pounds, or upwards, be sent therewith, to satisfy the Charge of the Maintenance and Education thereof ’, would be received.44 In addition it had been made clear that no questions would be asked of those who delivered the cash and the over-age infant, not even their names.45

Through this decision the Governors had surrendered the moral high ground by appearing to express an admission policy diametrically opposed to that envisaged by Coram. Idealistically, he had proposed an asylum open to all eligible children, particularly the poor, abandoned and unwanted. Now it was really just a question of money, with the hospital’s age restriction waived for those rich enough to pay a fee of £100. The possible abuses and embarrassments inherent in this financially driven policy were many and obvious, including the fact that it immediately removed credence from any defence that the Foundling might offer to those who accused it of being a resort of convenience for wealthy courtesans, no more than an off-shoot of London’s highly efficient and profitable sex industry.

This view appears to be borne out by the record of a chilling little transaction that survives in the London Metropolitan Archives. It is a bond of agreement dated 8 October 1760 between a lawyer in Chancery Lane – acting for the anonymous parents – and the ‘Corporation of the Governors and Guardians of the Hospital’, which promises to pay them the sum of £100 ‘with interest at five per cent per annum’ providing they admit a ‘Child aged about six weeks which will be handed to them’.46 The child is obviously viewed as little more than a money-making commodity by the hospital. Despite the horribly compromising and shameful nature of this policy it remained in place until January 1801, a startling reminder of the hospital’s desperate financial worries during the decades after 1760.

The ignominy that had befallen the Foundling Hospital and its unsuccessful policies of admission led to much soul-searching and public debate. The institution’s very future was in serious jeopardy. The anonymous author of a pamphlet published in 1760 entitled The Tendencies of the Foundling Hospital in its Present Extent Considered, in Several Letters to a Senator raised the deeply awkward question that was then, more than ever, in the minds of many: has the Foundling Hospital ‘in the present Extended Plan of it…not a Tendency to incourage and to promote the Sin of concubinage, and of General Inordinate Carnality of Manners’, and was it not ‘a legal licentious Asylum for every Bastard (of every Whore, and of every Whoremonger, under the Name of a Foundling, even where, not One of them All is a Foundling’? The author also questioned the moral wisdom of the hospital’s policy ‘to conceal and protect from Public Infamy those who ought rather to be exposed to it’.47

Another pamphlet, published in 1761 and entitled Some Objections to the Foundling-Hospital Considered, by a Person in the Country to Whom They were Sent, took a more positive view. It pondered the proposition that the hospital was ‘an encouragement to vice and immorality, by making an easy provision for illegitimate children; and taking away, by concealment, shame, which is the due portion of vice’, and concluded that while the hospital might help conceal ‘lewdness’, it also ‘prevents those infinitely more to be dreaded consequences, of seeking to conceal it by destroying children before they come into the world, or immediately after their birth’, resulting in the ‘unnatural mother’ suffering an ‘ignominious death’ or, if pardoned, passing ‘her days neglected, despised, and too likely to become thence a common prostitute’.48

This pamphlet also raised an issue that after 1759 was to be honed into the cornerstone of the hospital’s defence. The author recalls that, when he first heard of the ‘erection of a Foundling-Hospital’, he ‘could not but consider [it] as likely to be of eminent service to the community’ since he was aware ‘that in one parish in London there were but two or three children alive at the end of the year, in which two hundred had been placed with parish nurses’. The horrendous death rate in parish workhouses was to become the justification for the hospital’s actions and its continuing existence; whatever the hospital had done wrong, its apologists argued, the parish authorities had done worse, over a far longer period of time.

As early as May 1758, when the hospital was in despair about the death-rate of its babies, it sought to place this tragedy in context by comparing its losses with those of parish workhouses. A sub-committee investigated and recorded in its minutes of 27 February 1758 the death-rate among infants in workhouses in the area covered by London’s Bills of Mortality from 1728–57: of 468,081 babies christened, 273,930 died under the age of two, that is, 587 out of every 1,000 born. The committee managed to present its own figures to suggest that ‘our loss from Lady-Day 1741 to the 31st December 1757 will be 406 out of each 1,000’.49

This theme was developed in meticulous manner in 1759 by Hospital Governor Jonas Hanway in his Candid Historical Account of the Hospital for the Reception of Exposed and Deserted Young Children. In this book, written in the darkest moment of the hospital’s existence, Hanway took the position that it should acknowledge its mistakes, argued that it could learn from them, and urged the reader ‘not to conclude that we cannot reform the evil’ without also destroying what was good about the hospital. In other words he warned they should not, in a moment of desperation, throw the baby out with the bathwater.50 He analysed the hospital’s policies or ‘plan’ and admitted there was a serious need for reform. For example, he took issue with the policy of secrecy as a means of protecting mothers from ‘shame’: ‘Those plead for secrecy who believe it is for the service of the commonwealth’ if the ‘amours in high life or in low’ are ‘concealed from the world’. But ‘it should be remembered that the fewer secrets a man has…probably the more innocent his life’. Secrecy may save the parents from shame, argued Hanway, but ‘the most certain way to prevent the effects of shame is to remove the temptation to the offence which created it’, and if secrecy and the ‘concealment of amours’ is intended for the benefit of the child, ‘to provide a foundling hospital for such a purpose…seems to be ridiculous, in such a nation as this’.51

But the main thrust of Hanway’s publication was to put the disaster that had overtaken the Foundling in the best possible light, and to do this he exploited the poor reputation of the parish workhouses, laboriously compiling statistics to ‘prove’ that the hospital was a far safer refuge for the young.

The fact that the child mortality rate of the Foundling Hospital during the darkest days of the late 1750s was no worse than that of the average workhouse was, however, no real defence. The Foundling Hospital had, at one level, been founded to put an end to such appalling death-rates among the young, not to match and continue them. In the event the Foundling Hospital survived the storm – but only just. Severely compromised, its loss of Government grants and much public financial support meant that it had to adopt a regime of strict economy and limit the number of infants it accepted, to the point where it hardly played any significant role at all in the struggle to save destitute children. Between March 1760 and February 1767 only 116 children were admitted because much of its time and limited resources were now spent dealing with the large number that had been admitted during the 46 months after June 1756.52 By 1766 the hospital still had 4,300 children on its hands. It was not until 1768, after many children had been apprenticed out, that the number was reduced to below 1,000.53

In January 1767 the hospital took stock of its current situation and its troubled past, and surveyed the numbers and fate of the children admitted since its inception. It confirmed that it had received 1,394 children before the ‘General Reception’ that started on 2 June 1756, of whom in 1767 it knew 889 to be dead. It had received 14,934 during the ‘General Reception’, of whom 10,204 were dead (around 350 less than Brownlow calculated 90 years later), and 193 after the ‘General Reception’, of whom 56 were dead. According to these figures 63.5 per cent of those admitted before the period of ‘General Reception’ died, while 68.3 per cent of those admitted during the period of ‘General Reception’ had died. These statistics, considered fairly accurate, make nonsense of the optimistic statistic devised by Hanway in 1759 when he attempted to imply that the hospital’s death-rate during the troubled period of the ‘General Reception’ was ‘only’ 41–5 per cent.

A profile of the hospital’s activities in the two decades after 1760, when it was accepting very few children and generally attempting to pull itself together, is offered by twenty-five volumes of books that survive from 1768–1800 containing petitions made by mothers offering their children to the hospital.54 The volumes covering the decade between 1768 and 1779 have been analysed by Randolph Trumbach and some most revealing statistics emerge: they refer to 919 women, of whom 780 were ‘Spinsters’, 72 were ‘Wives’ and 21 ‘Widows’ (with the remaining few categorised as ‘others’). Of the ‘Spinsters’ offering children, most (751) did not declare their age, but of the 29 who did, 17 were between the ages of eighteen and twenty-three, which, points out Trumbach, was ‘exactly the age of most of the women who walked the streets as prostitutes’.55

So it seems that the hospital remained something of a refuge for the children of young harlots although the mothers’ ‘petitions’, in which they plead with the Governors to accept their children, never of course reveal whether a mother is also a prostitute. Instead, when explanations for pregnancy are offered, the petitioners generally fall back on the standard formulae – many no doubt true – of being seduced and deluded (often ‘under promise of marriage’) by fellow servants and absconded lovers, or else abandoned by husbands.

Reading these short letters, many written on behalf of the petitioners, remains an intensely moving experience. Bound into handsome eighteenth-century volumes, these ‘petitions’ open windows into a sad and desolate world in which mothers – most dogged by illness and poverty – consigned their offspring to the mercy and charity of strangers. For example, on 1 July 1772 Jane Brown explained in her petition that she was in ‘very low circumstances’, wanted every ‘common necessity’ and would ‘inevitably perish unless your Honours will be pleased to have my female Child, which is about 4 Months, under your Care, which will be a means of preserving us both from misery’. The petition is endorsed on the back: ‘To be admitted to be balloted for’ and, in red ink, ‘Dead, Aug 1st, 1772’. Whether this refers to Jane or her daughter is not made clear.

In early September 1777 Mary Eade explained that she had been ‘seduced by fair promises which have brought me into very low circumstances as I have done all that is in my power to hide this my misfortune from the World’ but had seen ‘an advertisement’ that ‘yr Honours would take in twenty Children on the 5th September next…and having no other prospect but be worse every day makes your Humble petitioner apply to your Honours in Hopes you will Consider my case so far as to believe me by taking my Child’.

Sarah Roper on 8 July 1772 stated that she had ‘been seduced by her Fellow Servant who Promised me marriage’ but ‘as soon as I…related my unexpressible Troubles to him he Immediately after absconded which has caused your Petitioner to be Brought to Entire Distruction’.56

Some of the petitions possess a particularly moving directness and simplicity. On 20 August 1776 Mary Smith of ‘Spittal Fields’, herself formerly a nurse in the hospital, addressed the Governors: ‘Gentlemen, It is with greatest Contrition for my past Folly that I humbly beg leave to implore your Protection for my poor helpless Infant who I fear will shortly be intirely destitute of the most common Necessities of life, its Father having gone to Sea & left me without any means for providing for its Subsistence.’ Receive ‘it into your Hospital’, she pleaded, ‘save it from misery’.57

Mary Eade, Sarah Roper and Mary Smith were all regarded as ‘real objects of charity’ and their babies were ‘admitted for ballot’, but not all children were. In August 1773 Margaret Williams told the Governors that she had ‘a Son who is in his apprenticeship and has the misfortune to have a Child laid to his charge witch I have supported from Birth…Witch has Entirely reduced Me as the Mother of the Child is gone away.’ Her petition was ‘rejected as the case is not an object of charity’.58

Despite the hospital’s slow steps forward the ghosts would not be laid. In the mid-1780s it once again considered the prospect of creating revenue by leasing some of its land to speculative house builders, which prompted another unfavourable response from the public. John Holliday, the author of a pamphlet that appeared in 1787 entitled An Appeal to the Governors of the Foundling Hospital, on the Probable Consequences of Covering the Hospital Lands with Buildings,59 did not hesitate to reinforce his arguments against the speculative development of the hospital’s fields by raking up the unpleasant past. He suggested that their ‘experiment’ with open admission was responsible for unleashing a ‘torrent of humanity’ that ‘broke down the barriers of virtue and morality’ and ‘introduced licentiousness among the lower orders of society’. The result was the weakening of ‘the force of the first passion of nature, the attachment of a parent to her offspring’ and ‘out of 14,934 children received from the 1st June 1756 to Ladyday 1760 more than 11,000 died’.60 Having reminded the hospital of its terrible errors of the past, the author could only hope that the current Governors would not make another serious mistake and ‘lose sight of the probable consequences…to their health and strength…of confining three hundred children within the walls of an hospital surrounded with buildings’.61

The hospital did not let its land for building in the 1780s but it did in the 1790s when its surveyor S. P. Cockerell devised an ingenious development plan for its estate that largely reconciled the institution’s need for fresh air and light with its need for money. Cockerell came up with the admirable compromise of placing large, well-planted squares on the west and east sides of the hospital so that it could continue to enjoy leafy open prospects even as terraces of houses rose around it through the late 1790s and into the first decades of the nineteenth century.

During this period, when its finances were starting to improve, the hospital still struggled to formulate an admission policy that was both morally and ethically correct and not open to abuse or liable to load the institution with calumny and debt. After January 1801, when the decision was taken to abandon the dubious policy of accepting any over-age child on payment of £100, the hospital gradually reformed the manner in which children were admitted. During the early decades of the nineteenth century it evolved a policy that each application for admission be decided on its merits following an interview with an ‘Enquirer’, but with certain conditions required: for example, that the child be under the age of twelve months, illegitimate or the child of a soldier or sailor killed in service of the country or with a father that ‘shall have deserted the child and not be forthcoming or cannot be compelled to maintain the child’. It was also preferable if the ‘petitioner’ was poor and without relations willing or able to support the child, and the hospital was most unwilling to accept any child born in a workhouse since it was therefore the parish’s responsibility to maintain it. But most important seems to have been the institution’s determination finally to rid itself of the bad reputation it had gained during the period of ‘General Reception’, when it was assumed to be – and no doubt was – a general repository for the offspring of harlots, and so, in the eyes of many, an open encouragement to vice.

Now the Governors – referring back to Coram’s initial vision – strove to rule out the prospect of serial recourse by harlots, insisting that a successful ‘petitioner shall have borne a good character previous to her misfortune or delivery…that her delivery and shame are known to few persons’, and that ‘in the event of the child being received, the petitioner has a prospect of preserving her station in society, and obtaining by her own exertions an honest livelihood’.62 If all these conditions were adhered to and all ‘petitioners’ thoroughly investigated, then harlots would almost certainly have been excluded from depositing their children in the Foundling.

So, in this atmosphere of extreme caution, the hospital’s fortunes revived and it entered the nineteenth century with a more considered system of selection and on a more secure financial footing. It had also, stung by earlier accusations of social irresponsibility, cast itself firmly in the role of moral campaigner – or at least guardian – against vice. Although this newly defined role looked back to some of the principles of the hospital’s founder it also anticipated the judgemental and rule-bound morality of the coming Victorian age.

The Magdalen House

The edition of the Rambler published on 26 March 1751 carried a letter in which a correspondent, who signed themselves ‘Amicus’, described their sensations when coming upon the nearly completed buildings of the Foundling Hospital:

As I wandered wrapped up in thought my eyes were struck with the Hospital for the Reception of deserted Infants, which I surveyed with Pleasure, till by a natural Train of Sentiment, I began to reflect on the Fate of the Mothers; for to what Shelter can they fly? Only to the Arms of their Betrayer, which perhaps are now no longer open to receive them; and then how quick must be the Transition from deluded Virtue to shameless Guilt, and from shameless Guilt to hopeless Wretchedness.

Amicus’ ‘train of sentiment’ was quick to connect ‘the Mothers’ of the infants lodged in the hospital with prostitution, for if these unmarried women were not prostitutes when they became pregnant, their subsequent ‘deluded Virtue’, ‘shameless guilt’ and ‘hopeless Wretchedness’ would almost certainly drive them to prostitution. This thought filled Amicus with compassion and, apparently, a strong desire to write to the editor of the Rambler, who, of course, was the renowned Dr Samuel Johnson.

The Anguish that I felt left me no Rest till I had, by your Means, addressed myself to the Publick on Behalf of those forlorn Creatures, the Women of the Town; whose Misery here might surely induce us to endeavour, at least their Preservation from eternal Punishment.

Amicus then put prostitutes in perspective and, in a sense, justified and forgave – or at least explained – their downfall:

These were all once, if not virtuous at least innocent, and might have continued blameless and easy, but for the Arts and Insinuations of those whose Rank, Fortune, or Education furnished them with Means to corrupt or to delude them…It cannot be doubted but that Numbers follow this dreadful Course of Life, with Shame, Horror, and Regret, but, where can they hope for Refuge?…Their Sighs, and Tears, and Groans, are criminal in the Eye of their Tyrants, the Bully and the Bawd, who fatten on their misery, and threaten them with Want and Gaol, if they shew the least Design of escaping from Bondage…There are Places, indeed, set apart, to which these unhappy Creatures may resort when the Diseases of Incontinence seize upon them; but, if they obtain a Cure, to what are they reduced? Either to return with their small Remains of Beauty to their former Guilt, or perish in the Streets with complicated Want.

In an attempt to unburden prostitutes of the crushing sense of guilt and shame that, it was imagined, drove them to debauchery and to identify those who were the real cause of their woes, he asked:

…how frequently have the Gay and Thoughtless in their evening Frolicks, seen a band of these miserable Females, covered with Rags, shivering with Cold, and pining with Hunger; and without either pitying their Calamities, or reflecting upon the Cruelty of those whom perhaps, first reduced them by Caresses of Fondness, or Magnificence of Promise, go on to reduce others to the same wretchedness by the same Means?

Finally Amicus observed that ‘to stop the Increase of the deplorable Multitude is undoubtedly the first and most pressing Consideration’ and then launched a general appeal for aid: ‘Nor will they long groan in their present Afflictions if all those were to contribute to their relief, that owe their Exemption from the same Distress to some other Cause, than their Wisdom and their Virtue.’

Amicus’ observations were immediately reprinted in the Gentleman’s Magazine, appearing in its March 1751 issue, which added a small postscript.63 It wished that the Rambler had ‘recommended some methods’ to achieve the admirable purpose stated, but since it had not, the Gentleman’s Magazine referred any readers who wanted to know more to a recently published pamphlet entitled The Vices of London and Westminster.64 The anonymous author of this pamphlet arranged his thoughts in ‘Five Letters’, the fourth of which contained a ‘proposal for an Hospital for the Reception of Repenting Prostitutes’. He seems to have possessed the calculating mind of a City merchant. If the sex trade revealed, in a most horrid manner, that every form of commerce could turn a profit and that everything – even a female’s body and her very soul – could be possessed, used and destroyed for a price – so perhaps might redemption be made to pay:

I think it would be an Act of great Benevolence, if amongst the many noble Charities established in the Metropolis, some Foundation were made for the Support and Maintenance of repentant Prostitutes; some such place, might even become an Ornament, and of use to the Kingdom, if these Women…were employed in a manufacture of Dresden-work, so much now the Mode, or in some easy Labour that might…help them earn their Bread…when they had behaved decently for a Year or two in such a Retreat, the most rigidly Virtuous need not scruple giving them Countenance and employment.65

The debate was continued the following month – April 1751 – in the Gentleman’s Magazine where another correspondent announced, ‘I have been considering what provision could be made for penitent prostitutes, and no method seems to me so proper as a foundation upon the plan of the convents in foreign countries.’ This correspondent – who signed themself Sunderlandensis – stressed the urgency and immensity of the problem by claiming that ‘lewdness is manifestly one of the great sources of the national calamity’ for it ‘corrupts the morals, and ruins the constitutions of the people’. Sunderlandensis also warmed to the notion that penitence could be profitable – or at least pay for itself – and urged that a ‘convent’ for ‘penitent prostitutes’ must include productive employment – perhaps lace-making – that ‘could benefit both them and the country as a whole’. Sunderlandensis widened the scope of such an institution by suggesting that it should also have a preventative purpose. It should offer refuge not only to penitent prostitutes but also to ‘seduced’ young women, to prevent them falling into prostitution, and each inmate should be obliged, on entry and under oath, to reveal the identity of their seducer, who would, presumably, subsequently be named and shamed.66

This correspondence, with the letter signed ‘Amicus’ perhaps the work of Samuel Johnson himself, brilliantly reflects the mid-eighteenth-century shift in attitude towards prostitution and prostitutes. England was wealthy and prided itself on its liberty, progressiveness and Christian virtues – yet it had a dark and intolerable flaw. London, one of the great trading centres of the world, included among its money-making activities a vast commerce in female flesh. The 1750s were a time of renewed moral introspection, expressed most famously in the sermons and writings of the influential Reverend Edward Cobden, notably his sermon entitled ‘A Persuasive to Chastity’ preached on 11 December 1748 at St James’s Palace ‘before’ the King.

This sermon – dealing with the importance of chastity and the evils of fornication – still makes sensational reading, the words almost smouldering on the page. Cobden told his grand congregation that ‘the sins of immodesty…are risen, perhaps, to a greater height, and spread to a wider extent than was ever known in former Ages: Insomuch that the two Sexes seem to vie with each other, which shall be most forward in disregarding all Rules of Decency, and violating the Sanctions of the Marriage Contract’. He then reminded the congregation of ‘those monstrous and unnatural Obscenities with which our Land hath been stained’ and sustained his argument with a biblical quote: ‘Whoremongers and Adulterers GOD will judge’.67 To make clear the consequences of a failure to reform, Cobden warned darkly of ‘Vengeance from Heaven’ and suggested that ‘the Judgements we of this Nation have lately suffered…have…in some Measure been owing to the Increase of the Sins of Uncleanness…among us’.68

One can’t help but wonder what effect all this had on George II, well known for his amours with the Countess of Suffolk and the Countess of Yarmouth, who in 1736 had borne him an illegitimate son.