Interlude

Colonel Francis Charteris

Colonel Francis Charteris

Francis Charteris was a dark and much-hated figure in early-eighteenth-century London: an urban ogre and brutal serial sexual predator. Given his contemporary notoriety it is not surprising that Hogarth should have chosen to portray him in scene one of The Harlot’s Progress as the man ogling Moll, the innocent country girl being procured for his delight by Mother Needham. His appalling career and final downfall tell us much about political chicanery during Sir Robert Walpole’s corrupt and greedy premiership. They also expose some of the darker undertones of sexual and moral corruption that were a hallmark of London life at the time.

The Newgate Calendar, published after Charteris’ conviction for rape in 1730, reveals the popular contempt in which he was held:

The name Charteris, during his life, was a terror to female innocence [and] may, therefore, his fate, and the exposure of his villainy, act as their shield against the destructive machinations of profligate men…It is impossible to contemplate the character of this wretch without the highest degree of indignation. A gambler, a usurer, an oppressor, a ravisher! Who sought to make equally the follies of men and the persons of women subservient to his passions.1

Charteris was a liar, a bully and a convicted rapist, so this public indignation is understandable. But its intensity reveals something else. He was a gentleman by birth but by his actions utterly betrayed the obligations of his caste. Gentlemen were not expected to be moral examples but they were expected to be brave and just. It was expected that they would drink and whore but it was not expected – indeed was not acceptable – that they should abuse their status or wealth to entrap, debauch, rape or mistreat defenceless woman (whores included) in a cowardly manner. Such aristocratic rogues as Charteris, along with conniving bawds and procuresses, were the popular villains of the Georgian sex industry, while warm-hearted prostitutes and ethically ‘honest’ outlaws, as personified by the free-spirited Macheath, were its heroines and heroes.

Charteris’ early career in the army revealed him to be a gambler and fraudster. He cheated his brother officers while in the Low Countries and was eventually court-martialled, found guilty and drummed out of his regiment. He retired to Scotland where he achieved considerable success as a professional gambler due to his ability to cheat brilliantly. With the fortune he made, he moved to London in the very early eighteenth century and prospered as a money-lender, particularly of mortgages, and so helped to fund both the speculative construction of houses and the purchase of leases on them in an attempt to profiteer through excessive rents.

Charteris loved young women almost as much as he loved money, as was made abundantly clear by the biographies of him that appeared after his trial. The History of Colonel Francis Ch—rtr—s of 1730 told the curious public that:

The Colonel…had by his address in Gaming, purchased several Seats, one of which, call’d Hornby Castle, in Lancashire, was peculiarly devoted to the Service of the blind Deity Cupid, on whose Altar the Colonel is said to have offered up more Sacrifices than any Man in Great Britain. Here Mr Ch—rtr—s, like the Grand Seignior, has a Seralio, which was kept in more than ordinary Decorum, under the inspection of a venerable Matron.

Charteris occupied his London house in the same manner and it was here that he lodged the seventeen-year-old Sally Salisbury in 1709. As the Newgate Calendar explains:

…his house was no better than a brothel…he kept in his pay some women of abandoned character, who, going to inns where the country wagons put up, used to prevail on harmless young girls to go to the colonel’s house as servants, the consequence of which was, that their ruin soon followed…His agents did not confine their operations to inns, but, wherever they found a handsome girl, they endeavoured to decoy her to the colonel’s house.

It was in this manner that, in 1729, the young Ann Bond fell into Charteris’ hands – with catastrophic consequences for them both.

The Colonel’s ‘agent’ – or procurer – in the case of Ann Bond was Mother Needham. She was passing Ann’s lodgings, saw the attractive young woman sitting outside and, as the Newgate Calendar explains, ‘addressed her, saying, she could help her to a place in the family of Colonel Harvey; for the character of Charteris was now become so notorious, that his agents did not venture to make use of his name’. It is the substance of this event that forms the first scene of Hogarth’s Harlot’s Progress.

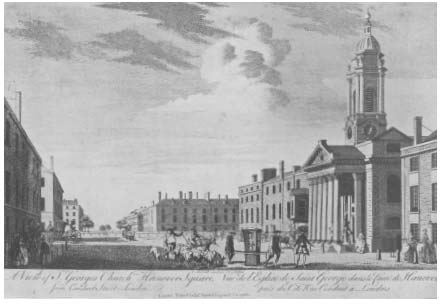

The fashionable area around St George’s Church, Hanover Square. The notorious Colonel Charteris lived in George Street (foreground).

Ann accepted the offer and was conducted to the Colonel’s grand house in George Street, near the newly built and very fashionable Hanover Square. This quarter, presided over by the mighty and just completed St George’s Church in which Handel worshipped, was the domestic centre and powerbase of the ruling Whig hegemony, of whom Charteris, by birth and connections, was part. Although no doubt useful for contributing funds, he must also have been something of an embarrassment to the party for he was known and loathed by the mob, as well as many of his respectable neighbours, for his lewd conduct. On at least one occasion a crowd had laid siege to his George Street house in order to obtain the release of a girl who had been decoyed to within its walls.

When first introduced to Ann, Charteris cut a fine and benevolent figure. He interviewed her, declared she would make a fine servant and hired her on wages of £5 a year. He immediately redeemed some of the clothes she had been obliged to pawn and, as The History of Colonel Ch—rtr—s explains, quickly attempted to make her obliged and indebted to him. Charteris ‘then bought her Holland [a type of linen] for shifting [i.e. for turning into undergarments] and promised she would have a clean shift every day’. Ann modestly refused so Charteris increased the value of what she must by now have realised was offer of payment for her sexual services. He tried to give her a fine snuff-box which Ann also refused, and then, according to the Newgate Calendar, he finally offered her an annuity for life and a house if she would lie with him. She refused. Realising by then that he could not purchase her favours, Charteris changed his strategy and started to employ intimidation and bullying. He was, after all, a middle-aged gentleman and master of the household and Ann nothing but a poor, defenceless young servant, one of his ‘family’ of resident women. The History relates how ‘some time after she was inform’d by the Housekeeper that she must lye in her Master’s Room, because he was very much indispos’d, wherefore she must lye in the Truckle-Bed’. It was a not uncommon practice for servants to sleep in the same room as their masters or mistresses, usually on a simple truckle-bed that could be wheeled away or folded and stored out of sight during the day. Several times in his diary Pepys records the practice: for example, in the entry for 9 October 1667, ‘my wife and I in the high bed in our chamber and Willet [the maid] in the trundle-bed’.2 But this was no doubt with the married couple’s privacy protected by heavy curtains surrounding the bed. Charteris, a predatory male, would be sleeping alone and Ann only a few yards away.

The History records that she was very sensibly hesitant, but ‘consented on being assured that the Curtains were so close drawn about the Bed that the Colonel could not see her undress’. Of course, Ann was foolish in consenting to the arrangement but presumably was under pressure from all quarters.

In the night the Colonel order’d the Housekeeper to come to bed with him, which she accordingly did, after which he call’d the Girl, but she would not comply, which very much incensed him, and made him swear execrably.

At around this time Ann discovered Charteris’ true name and, knowing something of his reputation, told the housekeeper that she wanted to leave. The housekeeper informed the Colonel, who was furious. He threatened to shoot Ann if she left his service, had her imprisoned in the house and treated her with disdain. As The History explains, ‘finding no Arguments, not even Gold, would prevail on her, he resolved to have recourse to force’. So on 10 November, in the morning, Charteris called Ann to his chamber, ordered her to stir the fire and, as she bent over to do so, ‘fastened the Door, and throwing her suddenly upon a Couch, cram’d his Night Cap into her Mouth to prevent her crying out, and enjoy’d her Nolens volens’.

After this ‘act of violence’, as the Newgate Calendar very simply puts it, Ann was ‘inconsolable, and not to be pacify’d by any Arguments he cou’d use’. Infuriated that she could not be paid to be silent, Charteris ‘took up a Horsewhip, and lash’d her very severely’ and then accused her of stealing 30 guineas and had her thrown out of the house. This must have been his usual contemptuous treatment of the poor and powerless women on whom he preyed. As well as physically abusing them, he abused his lofty social position and the law by threatening to denounce his victims as thieves on the assumption that his word as a gentleman would be believed above theirs as humble and placeless young women.

But with Ann, Charteris had made a fatal miscalculation. As the Newgate Calendar explains, ‘[S]he went to a gentlewoman named Parsons. And informing her of what had happened, asked her advice how to proceed.’ Mrs Parsons recommended that Ann get a warrant for assault and attempted rape, but when the evidence was heard by the Grand Jury it decided that the charge Charteris had to answer was not attempted rape ‘but actual commission of the fact’ – rape. Accounts differ about what happened next. Lord Chief Justice Raymond issued a warrant for Charteris’ arrest and some accounts say he avoided it being served upon him by fleeing to Brussels.3 On the other hand, the Newgate Calendar states that Charteris was arrested and carried in chains to Newgate. If this was the case he was soon free again because both accounts agree that he surrendered himself for trial in late February 1730.

If Charteris was arrested and quickly freed this was most likely due, once again, to connections. He had married the daughter of Sir Alexander Swinton. His wife duly bore him a daughter who in 1720 had married the Earl of Wemyss. The earl, being in London at the time of his father-in-law’s arrest, procured a writ of Habeas Corpus, in consequence of which Charteris was bailed. Why did Wemyss do this? Why would he support his frightful father-in-law who could only have brought shame and suffering on his wife and daughter? Perhaps Wemyss simply thought that by extracting Charteris from Newgate he was doing his best to save the family from further disgrace. But it is also possible that Wemyss himself was part of Charteris’ dissolute social circle. His character is now far from certain, but there is a clue in the name used by a notorious Covent Garden prostitute. It was usual for whores to take the surname of their most constant protector and it’s reasonable to assume that the notorious one-eyed Betsy Wyms (or Wemys) – the friend of Lucy Cooper – was paying this compliment to Charteris’ son-in-law.

Charteris duly came to trial on 28 February 1730 and the event proved to be a sensation. His lawyers tried to destroy the character and evidence of Ann Bond, to present her not as a victim but as a lewd and scheming whore. Charteris himself asked Ann if she had not told some of his household that: ‘[S]ince I had so much Silver, I should have my Instrument tipp’d, for it would not please a Woman?’ But this approach failed to sway the jury. Charteris had been a notorious libertine and cheat for nearly thirty years and now he was to pay the price. The jury found him guilty. On 2 March 1730 he was sentenced to death and carried through a howling mob to await his fate in Newgate.

Charteris had been too arrogant, made overconfident by his years of unrestrained abuse and the belief that his network of influential connections put him beyond the reach of the law. The verdict of this trial suggested he had been mistaken. Or had he? Lord Wemyss soon got to work again pulling strings. The Newgate Calendar records that ‘Lord Wemys [sic]…caused the Lord President Forbes to come from Scotland, to plead [Charteris’] cause before the Privy Council’ and, incredibly, as if to confirm the corruption of the age and Charteris in his arrogance, in April 1730, on the advice of the Privy Council, George II granted him a Royal Pardon. But the convicted felon had to pay dearly for his reprieve. He was obliged to settle a handsome annuity on Ann Bond as well as handing over large bribes to Lord President Forbes, who was assigned an estate of £300 per annum for life for his services, and Sir Robert Walpole, who in the autumn received ‘generous gifts’ from Charteris.4

The tale told by this trial is complex and ultimately depressing. A humble young girl could – if her character was unimpeachable – receive justice if abused by a rich and powerful man, but only perhaps if that man had as dark and evil a public reputation as Charteris. But this show of justice could then be overturned if the guilty man was rich and well connected, and if he agreed to buy off his victim and pay out huge bribes. What message did this story carry to young, vulnerable and abused London women? It was a victory of sorts: Charteris was humbled, publicly humiliated, terrified and financially penalised.5 But if it had been a poor and humble man who had committed the crime, he would have died. That, of course, is exactly the moral of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera: ‘[T]he lower sort of People have their vices in a degree as well as the Rich: And…they are punish’d for them’. In other words, all people are capable of ill behaviour, but only the poor are penalised.

In this case the rich and well-connected man had been reprieved by other rich and well-connected men. So who were the real victors? Surely rich and well-connected men – the very ones who patronised establishments such as those run by Mothers Needham and Douglas. From this point of view the story offers a particularly ugly insight into eighteenth-century London’s essentially misogynistic society, one in which women – especially humble country girls – were considered inferior beings and the legitimate toys of men, particularly men of power and property.

Additionally, information from Old Bailey records suggests that it was not only the rich and socially powerful who got away with one particular crime in eighteenth-century London. In fact, most men got away with their criminal actions when the charge was rape. Six men, including Charteris, were tried for rape at the Old Bailey in 1730 – an unusually high number (between 1727–34 there were, on average, only two rape trials a year).

Of the six accused in 1730 only Charteris was found guilty, despite some very compelling evidence in the other cases, with one man being held in gaol so that his case could be pondered and he could perhaps be indicted for assault at the next assizes. The charge against him was eventually reduced because the female ‘prosecutor’ was just ten years old and considered too young to be put on oath. This decision was made despite the fact that the accused had been apprehended ‘lying upon the child’ with his ‘private member drawn’, and that he had, according to the victim – whose genital area was found by a surgeon to be ‘depressed on the interior’ – ‘offer’d to put his Nastiness into her mouth’.6 The five other accused men were all of relatively humble origins (one was from Stepney) so were not saved by riches or power. Most seem to have escaped punishment – which would have been death – because they were men, and a jury of male peers probably thought death too extreme a punishment for merely attempting to have forced sex with a female, even one as young as ten.

After the verdict London was flooded with accounts of Charteris and his trial. Most were extremely hostile to Charteris, who predictably was dubbed the ‘Rape-master general of Great Britain’, while some used the opportunity to publish mildly diverting obscenities. Some Authentic Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Ch—s, for example, informed its readers that Charteris liked ‘strong, lusty, fresh Country Wenches, of the first Size, their Buttocks as hard as Cheshire Cheeses, that should make a Dint in a Wooden Chair, and work like a Parish Engine at a Conflagration’.7

Colonel Charteris in the dock during his 1730 trial for rape.

This popular confusion of morality and traditional male usage and privilege is perfectly represented by a mezzotint that appeared immediately after the trial. It shows Charteris standing at the bar of the Old Bailey with his thumbs tied. Below the image is an inscription that is, presumably, ironic in its initial and violent support of the rights of men such as Charteris for it concludes with condemnation of his actions. But in its strident and sardonic couplets the inscription raises images that must reflect the firmly held opinions of those the print sought to satirise – probably the majority of London men. I wonder how many male readers failed to perceive the irony in this inscription?

It has an ambiguous start:

Blood! – must a colonel, with a lord’s estate,

Be thus obnoxious to a scoundrel’s fate?

Then it appears to become thunderingly misogynistic and contemptuous:

Brought to the bar and sentenced from the bench,

Only for ravishing a country wench?

Shall men of honour meet no more respect?

Shall their diversions thus by laws be check’d?

Shall they be accountable to saucy juries

For this or t’other pleasure? Hell and furies!

But finally the tone and target change:

What man through villainy would run a course,

And ruin families without remorse,

To heap up riches – if, when all is done,

An ignominious death he cannot shun?

Charteris, seemingly a broken man, was obliged to give up his dissolute and abusive life and in August dismissed his pimp John Gourlay and his other ‘agents’, was ‘reconciled’ to his wife and finally presented to the King as a reformed rake. This beastly man was treated as a ‘Prodigal Son’, but it was a show of hypocrisy. Charteris’ true nature could not be hidden or the public fooled.

Emboldened by his official rehabilitation, in September 1730 Charteris impudently sued the High Baliff of Westminster and other officials for seizing goods and estates in Middlesex, Lancashire and Westmorland that had been forfeited when he was convicted as a felon. Eventually he regained his property, but only after paying compensation of about £30,000. He also took what revenge he could upon Ann Bond. Soon after the trial she married a tavern keeper and attempted to set up premises in Bloomsbury that were to capitalise on her fleeting fame by having a painted head of Colonel Charteris as their sign. He didn’t much like the plan and arranged for the husband to be arrested for debt.

A page of the Newgate Calendar, detailing Charteris’ case.

Hated in London, Charteris retired to Edinburgh where he discovered he was no better liked. He died in February 1732, ‘in a miserable manner’, noted the Newgate Calendar, ‘a victim of his own irregular course of life’. He was buried in the family vault in Greyfriars churchyard among extraordinarily violent scenes when a furious mob tried to tear open his coffin to fill it with dead cats and mutilate his corpse. Charteris left his large fortune to the second son of his daughter and the Earl of Wemyss, perhaps the agreed recompense for Wemyss’ earlier and most vital service in saving his father-in-law – and his family – from the ignominy of a public execution.

This dreadful tale has one curious postscript. Charteris’ awful conduct not only provided a villain for Hogarth when painting The Harlot’s Progress but also appears to have made an impression on the novelist Samuel Richardson. In the late 1730s, when writing Pamela, he must surely have had the Colonel in mind, for in his novel Pamela, a servant, is beset by a master intent on seducing her. Richardson, however, decided to create a fictional world that improved on fact and portrayed Pamela not only resisting her seducer but ultimately having her virtue rewarded by winning his genuine love and a proposal of honourable marriage. This moralistic and unlikely tale proved immensely popular when published in 1740, and indeed did much to establish the epistolary novel (that is, one written in the form of a series of letters) as a literary form. But not all were taken with the plot’s contrived and sadly unrealistic form. Among the book’s sternest critics was Henry Fielding, who was inspired by his loathing of Richardson’s artifice to launch his own career as a writer of more earthy and realistic novels. First he wrote a direct spoof of Pamela – Shamela in 1741 – in which he revealed Pamela to be not a noble creature at all but a cunning and lascivious sham intent on entrapping her master into marriage, and, in 1742, the picaresque tale Joseph Andrews in which the accident-prone footman hero is Pamela’s brother. Throughout these works Fielding honed his skill as a writer of fiction and in 1749 published his masterpiece, Tom Jones, one of the best English novels of the eighteenth century. Arguably, then, the sexual excesses of Colonel Charteris – the quintessential monster of London’s sex industry – probably inspired some of the greatest literature of eighteenth-century Britain.