The Battle of Crete was quite unlike any other in the Second World War. A strange mixture of new and old, it combined the first and only airborne invasion of a major island with a guerrilla resistance from an earlier age. And the huge advantage of Ultra intelligence, the great breakthrough in signals intercepts, was fatally wasted by an Allied commander-in-chief with a First World War mindset who could not comprehend the revolution in modern warfare. The loss of Crete was the most unnecessary defeat of all in that initial period of Allied humiliation at the hands of Hitler’s Wehrmacht. Not surprisingly, this has made it one of the most controversial episodes of the Second World War.

The origins of this paratroop invasion were strange. Mussolini had exasperated Hitler with his invasion of north-western Greece in October 1940. Mounted with spectacular incompetence, this unprovoked attack not only unified the usually divided Greeks in a frenzy of patriotism and resistance, but also brought British military assistance in the form of some RAF squadrons to honour Churchill’s promise of support to the only other country left fighting the Axis. Hitler feared that British aircraft were well placed in Greece to bomb the Roumanian oilfields of Ploesti, his most important source of fuel. This convinced him of the need to eject the British and occupy Greece before he invaded the Soviet Union. And with the British victory over the Italians in North Africa, chasing them all the way back from Egypt to Tripolitania, he feared Mussolini’s downfall. He ordered a corps to be commanded by Generalleutnant Erwin Rommel to move to Libya in February 1941 and decided to occupy Greece.

The British could not yet be sure that Hitler was going ahead with plans to invade the Soviet Union. If he moved against Greece, then he might use that as a stepping-stone to attack south towards Egypt, the basis of British strength in the region focused on the Suez Canal. There were senior officers within the Wehrmacht who tried to persuade their Führer to follow this ‘Mediterranean strategy’, but Hitler had no intention of being deflected from his long-standing desire to crush the Soviet Union. He decided to secure his southern flank first and protect his ally Roumania before launching Operation Barbarossa.

In January 1941, the threat to Greece became clear in German signals intercepted and decoded by the British Ultra system. Churchill, convinced that Britain’s honour was at stake, diverted nearly sixty thousand men from the Allied forces in North Africa at this critical moment to help the Greeks fight the invasion from Bulgaria. German divisions started to move through Hungary into Bulgaria, both Axis allies. But then to everyone’s surprise, and Hitler’s fury, an anti-German coup d’état by Serbian officers in Belgrade overthrew the Yugoslav regent, Prince Paul. Hitler ordered the smashing of Belgrade in a series of bombing attacks called Operation Strafgericht – or ‘Retribution’. German divisions were redeployed to conquer Yugoslavia.

The Yugoslav army promptly collapsed. A member of the 2nd SS Division Das Reich boasted: ‘Did [the Serbs] perhaps believe that with their incomplete, old fashioned and badly trained army they could form up against the German Wehrmacht? That’s just like an earthworm wanting to swallow a boa constrictor!’ The Greeks, on the other hand, fought back with great bravery. Even the Germans were impressed.

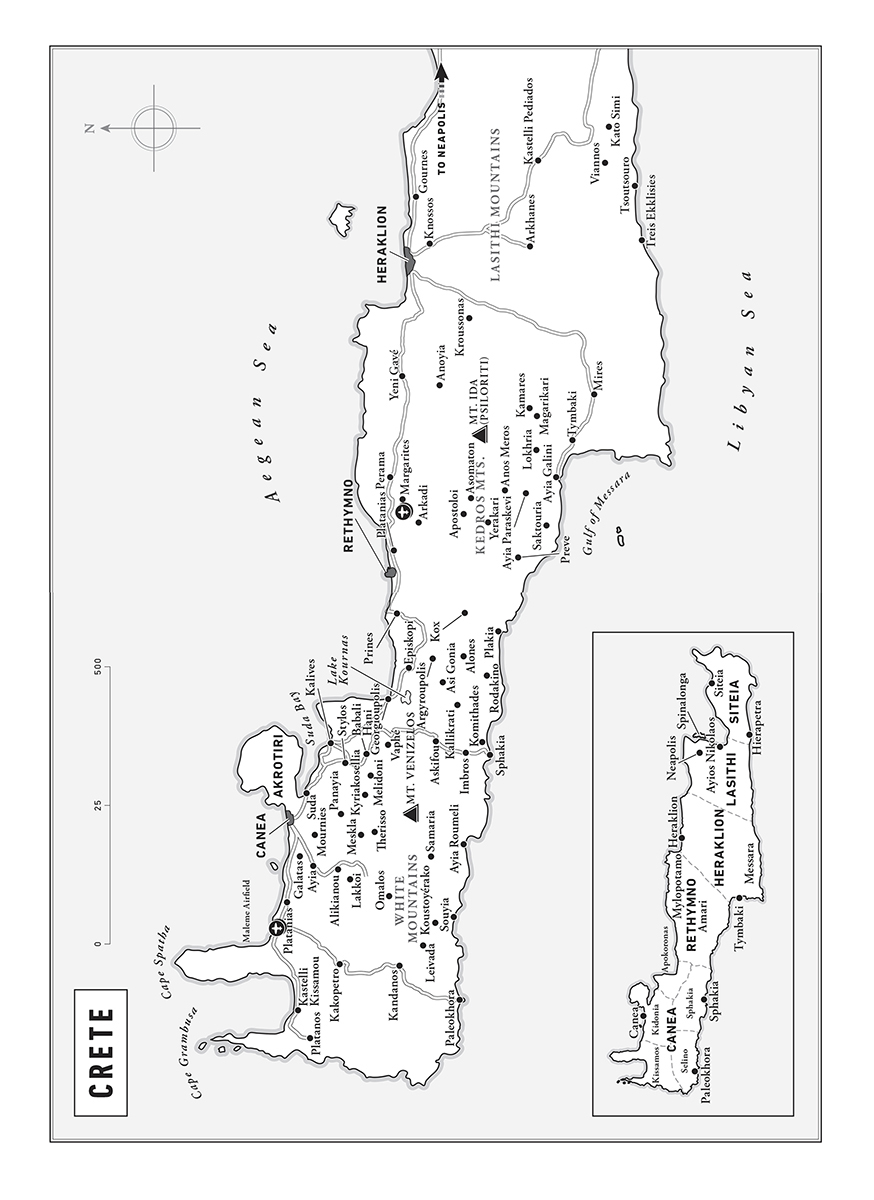

The Allied Corps, known as W Force, consisting of an Australian division, a New Zealand division and a British armored brigade, had to change positions rapidly. Positioned to face an attack from Bulgaria, they found that the unexpectedly rapid collapse of Yugoslav resistance meant that their left flank was threatened and the two Greek armies were completely out-manoeuvred. The British and Dominion forces pulled back, and harried by German air supremacy, the retreat south continued towards Athens, and then down into the Peloponnese. Thanks to Ultra intercepts of German signals, the British commander knew the enemy’s movements and was able to avoid being trapped. But after the defeats in Norway and France, this was the third time that British forces had to be evacuated by sea. Churchill’s debt of honour to the Greeks had achieved nothing at very great expense to the Allied troops in North Africa, now under attack from Rommel’s Deutsches Afrika Korps. All of W Force’s tanks and vehicles were lost, and it was a miracle that the great majority of the troops escaped. Most headed for Egypt, but the New Zealand division and several Australian battalions landed in Crete, assuming that they, too, would carry on to Alexandria.

Even before the occupation of Athens, senior German officers in the Luftwaffe began to study the feasibility of invading the island of Crete by air. Their paratroop division, the 7th Flieger Division, was an integral part of the German air force. After the great success of airborne assault in the capture of the Belgian fortress of Eben-Emael in May 1940, a feat which had prompted Hitler into a little dance of joy, they had longed for an even more ambitious objective.

This time, however, Hitler was rather less enthusiastic when Reichsmarschall Herman Göring took General der Flieger Kurt Student, the founder of Germany’s airborne force, to persuade the Führer of the merits of Operation Merkur, or Mercury. Hitler predicted a high casualty rate in the drop on Crete. He was even less convinced by the idea of a subsequent paratroop attack on Egypt to coincide with Rommel’s advance towards the Nile. But providing Operation Mercury did not delay the attack on the Soviet Union, he gave permission for the airborne invasion of Crete with the 7th Flieger Division to be followed by the 5th Mountain Division.

After numerous postponements, mainly due to delays in the arrival of fuel for the fleet of 250 Junkers transport aircraft, the date was finally set for 20 May. Churchill was fiercely encouraged at the prospect of this battle. The commander on Crete, Major General Bernard Freyberg VC, was a personal hero and friend of his. Thanks to Ultra, Freyberg had received details of General Student’s plan. He knew the exact time of the attack, and he knew the selected dropping zones. Both Churchill and General Sir Archibald Wavell, the commander-in-chief Middle East who had briefed Freyberg, were confident that the Allied forces could repulse the invasion. ‘It ought to be a fine opportunity for killing the parachute troops’, Churchill remarked in a typically pugnacious signal to Freyberg.

Freyberg, an exceptionally brave man of very limited imagination, unfortunately seized the wrong end of the stick. He could not imagine an island the size of Crete being taken solely by airborne troops. Part of the German signal decoded at Bletchley Park referred to some small ships coming later bringing stores and some reinforcements. (They were in fact wooden caique fishing boats.) Freyberg seized on this and convinced himself that the main attack was coming by sea. He even called it a ‘seaborne invasion’ when British intelligence in the Middle East knew that the Axis simply did not have the shipping or escort vessels for such a venture.

Freyberg’s son, Paul, the late Lord Freyberg, defended his father in a book published on the fiftieth anniversary of the battle with the title Bernard Freyberg VC: Soldier of Two Nations. He tried to argue that his father had such strict instructions on protecting the secrecy of Ultra that he felt he could not change the disposition of his forces. But Freyberg himself broke the rules on preserving Ultra secrecy. And most tellingly of all, he believed that the battle was as good as won when the Royal Navy in a murderous night action annihilated the Axis flotilla bringing the stores and reinforcements. Yet the battle was already lost, because the key airfield at Maleme was in German hands. Freyberg had allocated no more than a single battalion to its defence and had failed to give orders to crater the runway. He then failed to order a counter-attack until it was far too late.

The German attackers enjoyed air supremacy from their rapidly constructed airfields on the Greek mainland and on islands closer to Crete, so the defenders certainly faced a hard fight. Allied airfields on the north coast of the island had little warning of attack, and eventually the outnumbered pilots and planes were withdrawn to Egypt. But the surprisingly idle and incompetent German intelligence officers had severely underestimated the strength of British and Dominion troops on the island. Their positions were well camouflaged, and although they were subjected to days of air attack before the airborne invasion, the infantry was longing to get to grips with the German paratroopers. So were the Cretans themselves.

The Cretan population regretted bitterly that their own 5th Division had been trapped on the mainland, with all their young men. So boys and old men, sometimes led by their priest, emerged from their villages armed with shotguns and muzzle-loaders from fighting the Turkish occupiers. The favourite toast of one warrior priest was ‘May the Almighty polish the rust from our rifles!’ Many women came, too, brandishing kitchen knives, and they all set off to fight these new invaders. German paratroopers, trapped with their canopies caught in olive trees, were dispatched with fierce enthusiasm. A British officer was shocked when the Greeks with him shot three wounded paratroopers. ‘We always do that’, one of them said. ‘It’s the best thing for them’. Luftwaffe officers, outraged at such contraventions of the laws of war, organised reprisals later, with mass shootings of villagers.

German anger was increased by their own heavy casualties, however inflicted. With four thousand killed and missing, of whom half were paratroopers killed on the first day, to say nothing of 350 aircraft destroyed, it was their bloodiest experience in the whole of the Second World War up until that point. Operation Mercury was very nearly cancelled during the first night of the battle, when it looked as if the assault had failed, but early the next morning, on 21 May, General Student risked another wave and his men managed to secure the ill-defended airfield at Maleme. Freyberg’s misunderstanding and the failure to counter-attack immediately meant that soon the Germans were landing the 5th Mountain Division by transport planes to reinforce the 7th Flieger Division. British and Australian troops, who had won their battles at the other two airfields near the towns of Heraklion and Rethymno, could not believe it when they heard that Allied forces were to be evacuated from the island. The Germans, on the other hand, were shaken by the cost of this Pyrrhic victory. Hitler would never agree to another major airborne operation after Crete.

Cretans, proud and brave, sometimes insanely so, and notorious for their braggadocio, had no intention of collaborating with their conquerors. Unlike in other occupied countries, the Cretan resistance, advised by British and later American officers, was seldom betrayed to the Germans despite their intense efforts to recruit informers. The Cretan guerrilla leaders, known as kapitans, were a colorful lot. The main ones at the time of the invasion were Manoli Bandouvas, who had moustaches like a water buffalo’s horns, Petrakogeorgis, and Antonis Grigorakis, known as Satanas. They had worked with John Pendlebury, an officer in Britain’s Special Operations Executive who was a distinguished archaeologist and had been curator at the Palace of Knossos. Pendlebury, a noted athlete with a swordstick, a glass eye and an air of mystery, could have been the original for Indiana Jones, but he was wounded by German paratroopers outside the capital, Heraklion, and then shot dead two days later.

Of the three main kapitans, Bandouvas was the most difficult to handle. Unlike Petrakogeorgis, a comparatively rich sheep-farmer, who was the most pro-British and dependable, Bandouvas was devious and only interested in extending his own power. The difficult task of the British SOE officers was to build up the Cretan resistance ready for a mass uprising if the Allies decided to re-invade the island, but in the meantime make sure that the kapitans did not act rashly and provoke savage German reprisals. All the British intended to do was to carry out acts of sabotage against German airfields and ships carrying supplies and reinforcements to Rommel’s forces in North Africa.

The Cretans, longing for vengeance against the German occupier, could not understand why the Allies did not come to retake the island. Exasperation grew and confidence in the Allies declined. Cretans naturally saw their island as the centre of the war, so British liaison officers had a hard time explaining the other priorities of Middle East Command in Cairo, while trying in vain to reassure them that Crete was not seen as a backwater. But the Allied invasion of Sicily and then Italy in 1943 indicated that Greece would be left until the end of the war.

This painful paradox prompted Major Patrick Leigh Fermor to plan the most famous and controversial act of resistance. His idea was for a combined British and Cretan team to kidnap a German general and exfiltrate him by sea back to Cairo. The intention was to give the Cretans a huge boost, yet at the same time to avoid bloodshed. They would pretend that the ambush was carried out only by British commandos so that the Germans would have no excuse to exact reprisals on the civilian population. This escapade in April 1944 formed the basis of the movie Ill Met by Moonlight, with Dirk Bogarde playing the part of Leigh Fermor. There were heavy reprisals despite all of Leigh Fermor’s efforts to avoid them, but these savage acts were almost certainly linked to other factors, especially the German preparation to withdraw from eastern and central Crete to a western defence sector based on the ancient Venetian port of Chania. A stalemate then ensued until the end of the war.

German forces on Crete did not surrender until 9 May 1945, once they received orders from Grand Admiral Dönitz in Flensburg. They were not disarmed for another two weeks, when a British battalion arrived from mainland Greece, almost four years to the day after the German airborne assault. The surrender terms had allowed German troops to keep their weapons until then to make sure that Cretan guerrilla bands did not exact revenge for the invasion and long occupation.

Greeks are still tempted to believe that the defence of their country and the battle for Crete forced Hitler to delay the invasion of the Soviet Union until late June, with fatal results. Hitler, too, convinced himself of this idea late in the war to explain his failure to crush the Red Army utterly in 1941 as he had promised. But other elements played a much greater part, as we shall see.

Although I do not relish counter-factual speculation, it is, however, well worth considering what the consequences might have been if General Student had called off the invasion after that disastrous first day, or if General Freyberg had launched an immediate counter-attack on Maleme airfield. Hitler would not have agreed to a second attempt and the Axis simply did not have the naval resources in the eastern Mediterranean to launch the seaborne invasion which Freyberg feared. On the other hand, the British in the Middle East did not have the resources to maintain the island. But if Crete had been held, it would have provided a forward airbase for long-range B-24 Liberators to attack the Ploesti oilfields in Roumania once they were deployed in the region. In any case, the Battle of Crete was a very close-run thing, and the bravery shown on both sides, and by the Cretans themselves, makes it one of the most memorable of the whole war.

ANTONY BEEVOR

London, September 2013