15

Stalemate at Rethymno and Heraklion

21–26 MAY

If events at Maleme had followed the pattern at Rethymno and Heraklion, then the Germans would have lost the battle of Crete.

At Rethymno, where Campbell and Sandover demonstrated the necessary virtue of rapid counter-attack, the 2nd Parachute Regiment never had a chance to organise. To make matters worse, neither Kroh’s group, barricaded in the olive oil factory at Stavromenos, nor Wiedemann’s, dug in round Perivolia, had a wireless. Attempts to drop them one, then to land one by a Fieseler Storch light aircraft, all failed. They were also short of food. A goat unwise enough to show itself near the olive oil factory was soon butchered and cooked with sea water in ammunition boxes over a rapidly prepared fire.

The Australians had spent most of 21 May mopping up and reorganising after the morning’s successful counter-attack on Hill A. The 4th Greek Regiment advanced on the olive oil factory from the south, while the 5th Greek Regiment and Sandover’s 2/11th Battalion turned on Wiedemann’s group at Perivolia.

Sandover had not only benefited from the German operational order which he had translated in Colonel Sturm’s presence; his men had also captured the instructions for ground-to-air communication with a quantity of the necessary flags and signal panels. His companies were therefore able to lay out the swastika flags and appropriate tapes to direct air strikes by German bombers and fighters on to their own troops, and call for resupply by parachute. The paratroopers, without any form of wireless contact with the mainland and reduced to writing messages in the sand, could do little to prevent this.

The olive oil factory with its thick walls proved a tougher fortress than Campbell had at first imagined. A co-ordinated attack on 22 May with the 2/1st Battalion and the 4th Greek Regiment failed because of linguistic confusion over the plan.

That night Sandover’s 2/11th Battalion began to advance on Perivolia, with leap-frog attacks along the shore. But an unfortunate misunderstanding which had led to a clash between Greek and Australian troops on an earlier occasion prompted him to halt his companies short of the objective. The Greeks had swung round to the south, and with Cretan guerrillas, including the heavily armed monk, were harassing Wiedemann’s flank.

A virtual stalemate continued for several days at both Perivolia and Stavromenos until, on 25 May, Campbell’s men suddenly captured the olive oil factory after a bombardment with the remaining shells from the field guns. But inside they found only German wounded. Major Kroh, and all men capable of walking, had escaped.

Meanwhile Sandover’s men experienced some bloody fighting in attacks on Perivolia. They captured some of the outlying houses, but then the Germans blasted them with light anti-tank weapons. The two Matildas damaged in the early fighting near the airfield were repaired and, with improvised crews, driven back towards Perivolia for another night attack, but they were knocked out. Sandover came to the conclusion that, without heavy weapons, any more attacks would only lead to a waste of lives. In any case, the force at Rethymno had more than fulfilled their orders to deny the airfield and the port to the enemy.

• • •

At Heraklion, many of Colonel Bräuer’s paratroopers were in a sorry state. Thirst on the first night led to dysentery from drinking stagnant water out of irrigation ditches. Some chewed vineleaves in a desperate attempt to find liquid. Many lost their lives in the search for water, picked off by Cretan irregulars who then armed themselves with their weapons. During the first forty-eight hours, the worst was reserved for those on their own, still lying wounded where they had fallen, dehydrated and at the mercy of armed Cretans, or in some cases British soldiers and officers.

Yet for the British and Australians, killing became less impersonal after the initial blood-letting. The faceless dangerous silhouettes who had descended from the sky began to take on human guise. A 17-year-old whimpering in fear, with a smashed leg, was no longer an aerial stormtrooper, but an overgrown child, even if he had come to kill. When soldiers were told to remove all papers from the dead, including poignant photographs of sweethearts and families, they felt curiously at one with their enemy, a long way from home on a foreign battlefield. By the nature of their profession, soldiers are apt to swing from violence to sentiment.

A tacit agreement became established between the opposing sides that, during the relative quiet of the night, rations, water and ammunition were distributed, the dead were buried, and casualties evacuated. But for the Cretans, this was not a foreign battlefield: it was their homeland, violated without justification. They were in no mood either for compassion or for surrender.

When Major Walther received orders from Colonel Bräuer to gather his men and march in from the east to relieve Blücher’s men, cut off in the midst of the Black Watch on the hill south of the airfield, he discovered that one of his platoons, Lieutenant Lindenberg’s, had been completely annihilated by Cretan civilians. Altogether he is said to have lost some 200 men from Cretan irregulars round Gournes where his battalion dropped.

The platoon of Lieutenant Count Wolfgang von Blücher began its final stand on 21 May, a drama which became a rich source of myth. For the rest of Walther’s battalion, relieving their comrades in the midst of the Black Watch was more than just a point of honour. But the Scottish infantry was well dug in with unrestricted fields of fire.

In their small bowl in this rocky landscape south of the airfield, Blücher’s platoon had tried to scrape trenches with helmets and fingers to escape the fire of Vickers machine guns, the odd mortar bomb and even a few shells from a Bofors firing from its sand-bagged position beside the end of the runway. Blücher and many of his men were wounded. The platoon, soon down to less than half its effective strength, ran out of field dressings and became very short of ammunition.

At that point, according to the story, a horseman was seen galloping towards them with ammunition boxes tied to his saddle. This spectacle caused amazement at first in Scottish ranks, then attracted their fire. But the rider and the horse were hit only as they reached the besieged platoon.

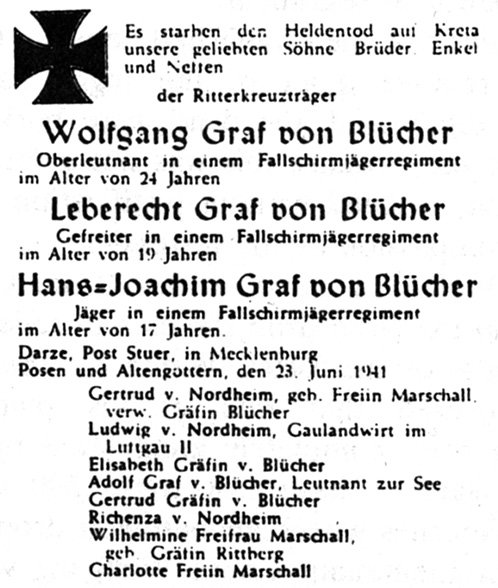

As the ammunition was passed rapidly around, the lieutenant asked how the rider was. He learned that the horseman was his 19-year-old brother, Leberecht, and that he was dead. Next morning, Wolfgang, the eldest of the three brothers, was killed along with the survivors of his platoon. The youngest brother, Hans-Joachim, was also killed, but his body was never found.*

The Blücher family’s announcement of the three deaths

At Knossos, eight kilometres south of Heraklion, Manolaki Akoumianakis, who had been Sir Arthur Evans’s chief assistant in the Minoan excavations, vowed to fight the parachutists after hearing that his eldest son, Miki, had been killed serving with the Cretan Division in Epirus. He sent his wife and other children to stay with relations in the mountains. And on receiving a message from John Pendlebury that the ridge opposite Knossos was vital, Manolaki Akoumianakis led a group of Greek soldiers and Cretans there. The Villa Ariadne, which had been turned into a British military hospital, came under mortar fire, but little damage was done either to the house or the site of Knossos itself.

Manolaki was the first killed in this attack against the paratroopers: he was about two hundred metres ahead of the Greek soldiers he had led there. Yet Miki, his son, was alive: the report had been mistaken. Miki Akoumianakis returned to Crete not long afterwards and made a proper grave for his father in spite of the German edict forbidding the burial of any civilian killed bearing arms. Later, during the occupation, he took over the Allied intelligence network in Heraklion and became the key British agent in the region for the last three years of the war.

Jack Hamson, also on Pendlebury’s orders and ignorant of his fate, continued to guard the small Plain of Nida on the eastern flank of Mount Ida against a landing by enemy gliders or troop-carriers. His hundred Cretan volunteers had grown restless on hearing the distant fighting round Heraklion. They wanted to go down to join the battle, yet Hamson felt obliged to exert what authority he had from Pendlebury to make them stay at their posts in case the Germans did try to land later in the battle. Starved of information as much as food, Hamson himself went down for supplies. He met Satanas at Kroussonas on the night of 24 May and heard of Pendlebury’s death. Returning to the Plain of Nida, he felt less certain than ever that the Germans were going to land there but was still obliged to continue if only in memory of Pendlebury.

• • •

Major Schulz’s battalion, after its withdrawal from within the city walls of Heraklion, remained hidden to the south and west. On 25 May they watched the heaviest bombing raid on the city. The destruction was terrible.

Schulz and his men received an order by wireless from Athens to swing on a long detour south-eastwards that night to join up with Colonel Bräuer. Schulz’s men moved in small parties to avoid being seen, but this fragmented move inland risked attack. Several guerrilla groups belonging to Pendlebury’s informal network, principally the bands of Petrakageorgis, Bandouvas and Satanas, inflicted heavy casualties. The Cretans were far better at night-fighting than either the British or the Germans.

The British and Australians at Heraklion had also watched the raid. Their feelings were divided between sorrow for the inhabitants and relief that they themselves were safely dispersed in their slit trenches. They had learned, like their counterparts at Rethymno, to confuse the pilots of the transport planes and bombers. They laid out captured swastika flags on their positions, stopped shooting and, when the Germans fired green Very lights, they did the same. On a number of occasions, captured recognition strips produced containers with weapons, ammunition, rations and medical supplies. Sets of surgical implements were parachuted, with true German practicality, in containers shaped like coffins to provide a second use. Two outstanding examples of this military manna from heaven were a pair of motor-cycles with side-cars, one dropped to Major Sir Keith Dick-Cunyngham’s company of the Black Watch and the other to the Australian battalion on the Charlies. The Australians found themselves so well provided with German weapons that large quantities could be handed over to the less fortunate Greek troops.

The Black Watch had become used to seeing only German aircraft in the sky, and when a lone Hurricane had landed on the runway in the middle of an air raid on 23 May they were astonished. One historian compared its arrival to ‘Noah’s dove’, but the pilot brought no promise of salvation. Six fighters had taken off from Egypt only to encounter heavy fire from Royal Navy vessels unused to finding friendly aircraft overhead. Two were shot down, and three more had to turn for home badly damaged. Another wave of six set out more successfully, but their long-range fuel tanks made them sluggish in combat. Only one aircraft out of the twelve survived. This belated attempt to provide air support was a thoroughly ill-considered gesture. Hurricanes had been needed earlier, operating from an airfield on the south coast properly established with fighter pens. The idea was not lacking, only the energy. On the day before this wasteful mission, Admiral Turle and General Heywood en route to Ay Roumeli had encountered a wing commander wandering in search of sites: as Turle pointed out, he was six months too late.

Despite the lack of air support, morale remained very high. Casualties equivalent to almost three parachute battalions had been inflicted on the first day and there was cockiness as well as bravery. During a dawn air raid Piper Macpherson from Lochgelly climbed out of his slit trench on the airfield to play reveille.

Brigadier Chappel has been criticized for not advancing against the severely reduced enemy to crush them, then marching to the aid of the New Zealand Division having cleared up Rethymno on the way. Chappel, although decisive on the first day, subsequently displayed little of the initiative Campbell and Sandover showed at Rethymno. Yet his caution is understandable: the 14th Infantry Brigade no longer had enough ammunition for a major engagement and Chappel had not had Sandover’s stroke of luck in discovering how few reserves the Germans possessed.

Chappel had also overestimated the strength of Bräuer’s force, because outer battalions sent in reports of large-scale reinforcements landing by parachute. These drops, which took place at too great a distance for their load to be identified, had consisted mainly of supplies. Since his orders had been to hold Heraklion and the airfield, he was reluctant to take risks by advancing outside his perimeter.

GHQ Middle East’s plan to pass units along the coast was optimistic. The idea was for the Argylls on the south coast at Tymbaki to move to Heraklion, then a battalion from Heraklion to move to Rethymno and so on. This was all very well on a map back in Egypt (or in Creforce Headquarters, for Freyberg also favoured the plan), but it did not take into account the state of the roads, the possibility that harassing attacks by German paratroopers might delay the Argylls’ advance northwards – their leading company with two Matildas only arrived at midday on 23 May – or that the coast road remained firmly blocked at Rethymno by the parachute battalion strongly dug in at Perivolia. Freyberg had sent a company of the Rangers from Suda but, lacking heavy weapons, they had had no more success than Sandover’s Australians. None of Chappel’s force could ever have reached Canea in time to influence the course of events at Maleme. He sent the two newly arrived Matildas, another of his own and some field guns to Suda by lighter, but they arrived only in time to strengthen the rearguard during the withdrawal.

So stalemate set in at both Rethymno and Heraklion. Their garrisons, ignorant of the sequence of disasters at Maleme, assumed that they had only to hold on and the German invasion would die on its feet. Once again, the lack of wirelesses had proved a grave weakness.