Like any good writing, your business school essays should be clear, concise, candid, structurally sound, and 100 percent grammatically accurate. Go ahead and get the story out, but then make sure to edit with a fine-tooth comb. Here’s how.

Clarity and conciseness are usually the products of a lot of reading, re-reading, and rewriting. Without question, repeated critical revision by yourself and by others is the surest way to trim, tune, and improve your prose.

Candor is the product of proper motivation. Honesty, sincerity, and authenticity cannot be superimposed after the fact; your writing must be candid from the outset. Also, let’s be frank: You’re probably pretty smart and pretty sophisticated. You could probably fake candor if absolutely necessary, but you shouldn’t. For one thing, it’s a hell of a lot more work. Moreover, no matter how good your insincere essay may be, we’re brazenly confident that an honest and authentic essay will be even better.

Structural soundness is the product of a well-crafted outline. It really pays to sketch out the general themes of your essay first; worry about filling in the particulars later. Pay particularly close attention to the structure of your essay and to the fundamental message it communicates. Make sure you have a well-conceived narrative. Your essay should flow from beginning to end. Use paragraphs properly, and make sure the paragraphs are in a logical order. The sentences within each paragraph should also be complete and in logical order.

It is critical that you avoid all grammatical errors. We just can’t stress this enough.

You aren’t allowed to misspell anything. You aren’t allowed to use awkwardly constructed or run-on sentences. You aren’t allowed to use verbs in the wrong tenses. You aren’t allowed to misplace modifiers. You aren’t allowed to make a single error in punctuation. A thoughtful essay that offers true insight will stand out, but if it is riddled with poor grammar and misspelled words, it will not receive serious consideration. In fact, making sure your essays are 100% grammatically accurate is so important that we’ve prepared a little primer for you. Even if you’re already a brilliant writer, it can’t hurt to have a little review,

Don’t neglect your spelling and grammar check

We imagine you’ll probably write your essay on a computer. It’s a very good idea. Use a computer with a spell-checker. Turn on the spelling- and grammar-checking options. Your computer is only as smart as you are, so carefully consider the advice your computer offers. Your computer is not going to know the difference between “there” versus “their,” but you should.

Chances are you know the difference between a subject and a verb. So we won’t spend time here reviewing the basic components of English sentence construction (however, if you feel like you could use a refresher, check out our book, Grammar Smart.) Instead we will focus on problems of usage.

Below is a brief overview of the seven most common usage errors among English speakers. These are errors we all make (some more than others) and knowing what they are will help you snuff them out in your own writing.

A modifier is a descriptive word or phrase inserted into a sentence to add dimension to the thing it modifies. For example:

Because he could talk, Mr. Ed was a unique horse.

Because he could talk is the modifying phrase in the sentence. It describes a characteristic of Mr. Ed. Generally speaking, a modifying phrase should be right next to the thing it modifies. If it’s not, the meaning of the sentence may change. For example:

Every time he goes to the bathroom outside, John praises his new puppy for being so good.

Who’s going to the bathroom outside? In this sentence, it’s John! There are laws against that! The descriptive phrase every time he goes to the bathroom outside needs to be near puppy for the sentence to say what it means.

When you are writing sentences that begin with a descriptive phrase followed by a comma, make sure that the thing that comes after the comma is the person or thing being modified.

As you know, a pronoun is a little word that is inserted to represent a noun (he, she, it, they, etc). Pronouns must agree with their nouns: The pronoun that replaces a singular noun must also be singular, and the pronoun that replaces a plural noun must be plural.

During your proofreading, be sure your pronouns agree with the nouns they represent. The most common mistake is to follow a singular noun with a plural pronoun (or vice versa), as in the following:

If a writer misuses words, they will not do well on the state exam.

The problem with this sentence is that the noun (“writer”) is singular, but the pronoun (“they”) is plural. The sentence would be correctly written as follows:

If a writer misuses words, he or she will not do well on the state exam.

Or

If writers misuse words, they will not do well on the state exam.

This may seem obvious but it is also the most commonly violated rule in ordinary speech. How often have you heard people say, The class must hand in their assignment before leaving. Class is singular. But their is plural. Class isn’t the only tricky noun that sounds singular but is actually plural. Following is a list of “tricky” nouns—technically called collective nouns. They are nouns that typically describe a group of people but are considered singular and therefore need a singular pronoun:

Family

Jury

Group

Team

Audience

Congregation

United States

If different pronouns are used to refer to the same subject or one pronoun is used to replace another, the pronouns must also agree. The following pronouns are singular:

Either

Neither

None

Each

Anyone

No one

Everyone

If you are using a pronoun later in a sentence, double-check to make sure it agrees with the noun/pronoun it is replacing.

The rule regarding subject-verb agreement is simple: singular with singular, plural with plural. If you are given a singular subject (he, she, it), then your verb must also be singular (is, has, was).

Sometimes you may not know if a subject is plural or singular, making it tough to determine whether its verb should be plural or singular. (Just go back to our list of collective nouns that sound plural but are really singular).

Subjects joined by and are plural:

Bill and Pat were going to the show.

However, nouns joined by or can be singular or plural—if the last noun given is singular, then it takes a singular verb; if the last noun given is plural, it takes a plural verb.

Bill or Pat was going to get tickets to the show.

When in doubt about whether your subjects and verbs agree, trim the fat! Cross out all the prepositions, commas, adverbs, and adjectives separating your subject from its verb. Stripping the sentence down to its component parts will allow you to quickly see whether your subjects and verbs are in order.

As you know, verbs come in different tenses—for example, is is present tense, while was is past tense. The other tense you need to know about is “past perfect.”

Past perfect refers to some action that happened in the past and was completed (perfected) before another event in the past. For example:

I had already begun to volunteer at the hospital when I discovered my passion for medicine.

You’ll use the past perfect a lot when you describe your accomplishments to admissions officers. For the most part, verb tense should not change within a sentence (e.g., switching from past to present).

Remember this from your SATs? Just as parallel lines line up with one another, parallelism means that the different parts of a sentence line up in the same way. For example:

Jose told the career counselor his plan: he will be taking the GMAT, attend business school, and become a CEO.

In this sentence, Jose is going to be taking, attend, and, become. The first verb, be taking is not written I the same form as the other verbs in the series. In other words, it is not parallel. To make this sentence parallel, it should read:

Jose told the career counselor his plan: he will take the GMAT, attend business school, and become a CEO.

It is common to make errors of parallelism when writing sentences that list actions or items. Be careful.

When comparing two things, make sure that you are comparing what can be compared. Sound like double-talk? Look at the following sentence:

Larry goes shopping at Foodtown because the prices are better than Shoprite.

Sound okay? Well, sorry—it’s wrong. As written, this sentence says that the prices at Foodtown are better than Shoprite—the entire store. What Larry means is that the prices at Foodtown are better than the prices at Shoprite. You can only compare like things (prices to prices, not prices to stores).

The English language uses different comparison words when comparing two things than when comparing more than two things. Check out these examples:

more (for two things) vs. most (for more than two)

Ex.: Given Alex and David as possible dates, Alex is the more appealing of the two.

In fact, of all the guys I know, Alex is the most attractive.

less (for two things) vs. least (for more than two)

Ex.: I am less likely to be chosen than you are.

I am the least likely person to be chosen from the department.

better (for two things) vs. best (for more than two)

Ex.: Taking a cab is better than hitchhiking.

My organic chemistry professor is the best professor I have ever had.

between (for two things) vs. among (for more than two)

Ex.: Just between you and me, I never liked her anyway.

Among all the people here, no one likes her.

Keep track of what’s being compared in a sentence so you don’t fall into this grammatical black hole.

Diction means choice of words. There are tons of frequently confused words in the English language. They can be broken down into words that sound the same but mean different things (there, they’re, their), words and phrases that are made up (irregardless) and words that are incorrectly used as synonyms (fewer, less).

Words that sound the same but mean different things are homonyms. Some examples are:

there, they’re, their: There is used to indicate a location in time or space. They’re is a contraction of “they are.” Their is a possessive pronoun.

effect/affect: Effect is the result of something. Affect is to influence or change something.

conscience/conscious: Conscience is Freudian, and is a sense of right or wrong. Conscious is to be awake.

principle/principal: Principle is a value. Principal is the person in charge at a school.

eminent/imminent: Eminent describes a person who is highly regarded. Imminent means impending.

Imaginary words that don’t exist but tend to be used in writing include:

Alot: Despite widespread use, alot is not a word. A lot is the correct form.

Irregardless: Irregardless is not in anybody’s dictionary—it’s not a real word. Regardless is the word that you want.

Sometimes people don’t know when to use a word. How often have you seen this sign?

Express checkout: Ten items or less.

Unfortunately, supermarkets across America are making a blatant grammatical error when they post this sign. When items can be counted, you must use the word fewer. When something cannot be counted, you would use the word less. For example:

If you eat fewer French fries, you can use less ketchup.

Here are some other words people make the mistake of using interchangeably:

number/amount: Use number when referring to something that can be counted. Use amount when it cannot.

aggravate/irritate: Aggravate and irritate are not synonymous. To aggravate is to make worse. To irritate is to annoy.

disinterested/uninterested: Disinterest means impartiality; absence of strong feelings about something, good or bad. To be uninterested, on the other hand, indicates boredom.

Diction errors require someone to cast a keen, fresh eye on your essay because they trick your ear and require focused attention to catch.

Here’s a handy chart to help you remember the most common grammar usage errors:

Grammatical Category

Misplaced Modifier

What’s the Rule?

A modifier is word or phrase that describes something and should go right next to the thing it modifies.

Bad Grammar

1. Eaten in Mediterranean countries for centuries, northern Europeans viewed the tomato with suspicion.

2. A former greens keeper now about to become the Masters champion, tears welled up in my eyes as I hit my last miraculous shot.

Good Grammar

1. Eaten in Mediterranean countries for centuries, the tomato was viewed the tomato with suspicion by Northern Europeans.

2. I was a former greens keeper whowas now about to become the Masters champion; tears welled up in my eyes as I hit my last miraculous shot.

Grammatical Category

Pronoun Agreement

What’s the Rule?

A pronoun must refer unambiguously to a noun and it must agree in number with that noun.

Bad Grammar

1. Although brokers are not permitted to know executive access codes, they are widely known.

2. The golden retriever is one of the smartest breeds of dogs, but they often have trouble writing personal statements for law school admission.

3. Unfortunately, both candidates for whom I worked sabotaged their own campaigns by accepting a contribution from illegal sources.

Good Grammar

1. Although brokers are not permitted to know executive access codes, the codes are widely known.

2. The golden retriever is one of the smartest breeds of dogs, but often it has trouble writing a personal statement for law school admission.

3. Unfortunately, both candidates for whom I worked sabotaged their own campaigns by accepting contributions from illegal sources.

Grammatical Category

Subject-Verb Agreement

What’s the Rule?

The subject must always agree in number with theverb. Make sure you don’tforgetwhatthe subject of a sentence is, and don’t use the object of a preposition as a subject.

Bad Grammar

1. Each of the men involved in the extensive renovations were engineers.

2. Federally imposed restrictions on the ability to use certain information has made life difficult for Martha Stewart.

Good Grammar

1. Each of the men involved in the extensive renovations was engineers.

2. Federally imposed restrictionson the ability to use certain information have made life difficult for Martha Stewart.

Verb Tense

What’s the Rule?

Always make sure your sentences’ tenses match the time frame being discussed.

Bad Grammar

1. After he finished working on his law school essays he would go to the party.

Good Grammar

1. After he finished working on his law school essays he went to the party.

Grammatical Category

Paralell Construction

What’s the Rule?

Two or more ideas in a single sentence that are parallel need to be similar in grammatical form.

Bad Grammar

1. The two main goals of the Eisenhower presidency were a reduction of taxes and to increase military strength.

2. To provide a child with the skills necessary for survival in modern life is like guaranteeing their success.

Good Grammar

1. The two main goals of the Eisenhower presidency were to reduce taxes and to increasemilitary strength.

2. Providing children with the skills necessary for survival in modern life is like guaranteeing their success.

Grammatical Category

Cmparisons

What’s the Rule?

You can only compare things that are exactly the same.

Bad Grammar

1. The rules of written English are more stringent than spoken English.

2. The considerations that led many colleges to impose admissions quotas in the last few decades are similar to the quotas imposed in the recent past by large businesses.

1. The rules of written English are more stringent than those of spoken English.

2. The considerations that led many colleges to impose admissions quotas in the last few decades are similar to those that led large businesses to impose quotas in the recent past.

Grammatical Category

Diction

What’s the Rule?

There are many words that sound the same but mean different things.

Bad Grammar

1. Studying had a very positive affect on my score.

2. My high SAT score has positively effected the outcome of my college applications.

Good Grammar

1. Studying had a very positive effect on my score.

2. My high SAT score has positively affected the outcome of my college applications.

Now that we’ve got that covered, it’s time to talk about punctuation. As a member of the LOL generation you might be great at turning punctuation into nonverbal clues, but colons and parentheses have other uses besides standing in as smiley faces at the end of your texts.

A formal essay is not like the notes you take in econometrics. “W/” is not an acceptable substitute for with, and neither is “b/c” for because. Symbols are also not acceptable substitutes for words (@ for at, & for and, etc.). (In fact, try to avoid the use of “etc.”; it is not entirely acceptable in formal writing. Use “and so forth” or “among others” instead.) And please don’t indulge in any “cute” spelling (“nite” for night, “tho” for though). This kind of writing conveys a message that you don’t care about your essay. Show the admissions officers how serious you are by eliminating these shortcuts.

The overall effectiveness of your business school application essay is greatly dependent on your ability to use punctuation wisely. Here’s what you need to know:

Very few people understand every rule for proper comma use in the English language.

This lack of understanding leads to two disturbing phenomena: essays without commas and essays with commas everywhere. Here is a quick summary of proper comma use:

Use Commas to Set Off Introductory Elements.

Use Commas to Separate Items in a Series.

[Note: There’s always great debate as to whether the final serial comma (before the and) is necessary. In this case, the comma must be added; otherwise, there will be a question about the contents of the scrambled eggs. In cases where no such ambiguity exists, the extra comma seems superfluous. Use your best judgment. When in doubt, separate all the items in a series with commas.]

Use Commas Around a Phrase or Clause that Could Be Removed Logically from the Sentence.

Use a Comma to Separate Coordinate (Equally Important) Adjectives. Do Not Use a Comma to Separate Noncoordinate Adjectives.

Do Not Use a Comma to Separate a Subject and a Verb.

Do Not Use a Comma to Separate Compound Subjects or Predicates.

(A compound subject means two “do-ers”; a compound predicate means two actions done.)

Use a colon to introduce an explanation or a list.

Use a semicolon to join related independent clauses in a single sentence (a clause is independent if it can logically stand alone).

Use a dash for an abrupt shift. Use a pair of dashes (one on either side) to frame a parenthetical statement that interrupts the sentence. Dashes are more informal than colons.

Use exclamation points sparingly. Try to express excitement, surprise, or rage in the words you choose. A good rule of thumb is one exclamation point per essay, at the most.

Use a question mark after a direct question. Don’t forget to use a question mark after rhetorical questions (ones that you make in the course of argument that you answer yourself).

Use quotation marks to indicate a writer’s exact words. Use quotation marks for titles of songs, chapters, essays, articles, or stories—a piece that is part of a larger whole. Periods and commas always go inside the quotation mark. Exclamation points and question marks go inside the quotation mark when they belong to the quotation and not to the larger sentence. Colons, semicolons, and dashes go outside the quotation mark.

Now that you’ve gotten a refresher in the building blocks of good writing, it’s time to talk about the other half of the equation: style. If grammar and punctuation represent the mechanics of your writing, style represents the choices you make in sentence structure, diction, and figures of thought that reveal your personality to admissions officers. We can’t recommend highly enough that you read The Elements of Style, by William Strunk Jr., E. B. White, and Roger Angell. This little book is a great investment. Even if you’ve successfully completed a course or two in composition without it, it will prove invaluable and become your new best friend—and hopefully also your muse.

Remember: Good writing is writing that’s easily understood. You want to get your point across, not bury it in words. Make your prose clear and direct. If an admissions officer has to struggle to figure out what you’re trying to say, there’s a good chance he or she might not bother reading further. Abide by word limits and avoid the pitfall of overwriting. Here are some suggestions that will help clarify your writing by eliminating wordiness:

Don’t try to put too much information into one sentence. If you’re ever uncertain whether a sentence needs three commas and two semicolons or two colons and a dash, just make it into two separate sentences. Two simple sentences are better than one long convoluted one. Which of the following examples seems clearer to you?

Example #1:

Many people, politicians for instance, act like they are thinking of the people they represent by the comments made in their speeches, while at the same time they are filling their pockets at the expense of the taxpayers.

Many people appear to be thinking of others, but are actually thinking of themselves. For example, many politicians claim to be thinking of their constituents, but are in fact filling their pockets at the taxpayers’ expense.

In a 500-word essay, you don’t have time to mess around. In an attempt to sound important, many of us “pad” our writing. Always consider whether there’s a shorter way to express your thoughts. We are all guilty of some of the following types of clutter:

| Cluttered | Clear |

| due to the fact that | because |

| with the possible exception of | except |

| until such time as | until |

| for the purpose of | for |

| referred to as | called |

| at the present time | now |

| at all times | always |

Another way in which unnecessary words may sneak into your writing is through the use of redundant phrases. Pare each phrase listed below down to a single word:

cooperate together___________________________________

resulting effect___________________________________

large in size___________________________________

absolutely unprecedented___________________________________

disappear from sight___________________________________

new innovation___________________________________

repeat again___________________________________

totally unique___________________________________

necessary essentials___________________________________

A qualifier is a little phrase we use to cover ourselves. Instead of plainly stating that “Former President Reagan sold arms in exchange for hostages,” we feel more comfortable stating “It’s quite possible that former President Reagan practically sold arms in a kind of exchange for people who were basically hostages.” Over-qualifying weakens your writing. Prune out these words and expressions wherever possible:

| kind of | basically |

| a bit | practically |

| sort of | essentially |

| pretty much | in a way |

| rather | quite |

Another type of qualifier is the personal qualifier, where instead of stating the truth, I state the truth “in my opinion.” Face it: Everything you state (except perhaps for scientific or historical facts) is your opinion. Personal qualifiers like the following can often be pruned:

to me

in my opinion

in my experience

I think

it is my belief

it is my contention

the way I see it

If you choose the right verb or adjective to begin with, an adverb is often unnecessary.

Use an adverb only if it does useful work in the sentence. It’s fine to say “the politician’s campaign ran smoothly up to the primaries,” because the adverb “smoothly” tells us something important about the running of the campaign. The adverb could be eliminated, however, if the verb were more specific: “The politician’s campaign sailed up to the primaries.” The combination of the strong verb and the adverb, as in “the politician’s campaign sailed smoothly up to the primaries,” is unnecessary because the adverb does no work. Here are other examples of unnecessary adverbs:

very unique

instantly startled

dejectedly slumped

effortlessly easy

absolutely perfect

totally flabbergasted

completely undeniable

Rewrite these sentences to make them less wordy.

1. It can be no doubt argued that the availability of dangerous and lethal guns and firearms are in part, to some extent, responsible for the undeniable explosion of violence in our society today.

2. Why is it always imperative and necessary for the teaching educational establishment to subdue and suppress the natural spirits and energies of adolescents in scholarly settings?

3. It seems to me that I believe one must not ignore the fact that Hamlet was a heroic character as well as a tragic and doomed character fated to suffer.

4. No one would deny the strong and truthful fact that young teenage pregnancy is on the rise and is increasing at unbelievable rates each and every single day of the year.

Put each of the following sentences into the active voice:

1. The Constitution was created by the Founders to protect individual rights against the abuse of federal power.

2. Information about the Vietnam War was withheld by the government.

3. The right to privacy was called upon by the Supreme Court to form the foundation of the Roe v. Wade decision.

4. Teachers in many school districts are now often required by administrators to “teach to the test.”

5. Residents of planned communities are mandated by Block Associations to limit the number of cars parked in their driveways.

6. Mistakes were made by the President.

7. The gaze of the tiny porcupine was captured by the headlights of the oncoming Range Rover.

Pronoun agreement problems often arise because the writer is trying to avoid a sexist use of language. Because there is no gender-neutral singular pronoun in English, many people use they, as in the incorrect sentence above. But there are other, more grammatically correct ways of getting around this problem.

One common, albeit quite awkward, solution is to use he/she or his/her in place of they or their. For example, instead of writing, “If someone doesn’t pay income tax, then they will go to jail,” you can write, “If someone doesn’t pay income tax, then he or she will go to jail.” A more graceful (and shorter) alternative to he/she is to use the plural form of both noun and pronoun: “If people don’t pay income tax, they will go to jail.” Using nonsexist language also means finding alternatives for the word man when you are referring to humans in general. Instead of mankind you can write humankind or humanity; instead of mailman, you can use mail carrier; rather than stating that something is man-made you can call it manufactured or artificial.

There are a number of good reasons for you to use nonsexist language. For one thing, it is coming to be the accepted usage; that is, it is the language educated people use to communicate their ideas. Many publications now make it their editorial policy to use only non-gendered language. In addition, nonsexist language is often more accurate. Some of the people who deliver mail, for example, are female, so you are not describing the real state of affairs by referring to all of the people who deliver your mail as men (since it is no longer universally accepted that man refers to all humans). Finally, there is a good chance that at least one of your readers will be female, and that she—or, indeed, many male readers—will consider your use of the generic “he” to be a sign that you either are not aware of current academic conventions or do not think that they matter. It is best not to give your readers that impression.

Use of non-sexist language can feel awkward at first. Practice until it comes to seem natural; you may soon find that it is the old way of doing things that seems strange.

Style Category

Wordiness

What’s the Rule?

Sentences should not contain any unnecessary words.

Bad Style

1. The medical school is accepting applications at this point in time.

2. She carries a book bag that is made out of leather and textured.

Good Style

1. The medical school is accepting applications now.

2. She carries a textured, leather book bag.

Style Category

Fragments

What’s the Rule?

Sentence should contain a subject and a verb and express a complete idea.

Bad Style

1. And I went to the library.

Good Style

1. I went to class and I went to the library.

Style Category

Run-ons

What’s the Rule?

Sentences that consist of two independent clauses should be joined by the proper conjunction.

Bad Style

1. The test has a lot of difficult information in it, you should start studying right away.

Good Style

2. The test has a lot of difficult information in it, and you should start studying right away.

Style Category

Passive/Active Voice

What’s the Rule?

Choose the active voice, in which the subject performs the action.

Bad Style

1. The ball was hit by the bat.

2. My time and money were wasted trying to keep www.justdillpickles. com afloat single-handedly.

Good Style

1. The bat hit the bat.

2. I wasted time and money trying to keep www.justdillpickles.com afloat single-handedly.

Style Category

Nonsexist Language

What’s the Rule?

Sentences should not contain any gender bias.

Bad Style

1. A professor should correct his students’ papers according to the preset guidelines.

2. From the beginning of time, mankind used language in one way or another.

3. Are there any upperclassmen who would like to help students in their Lit classes?

Good Style

1. Professors should correct their students’ papers according to the preset guidelines.

2. From the beginning of time, humans used language in one way or another.

3. Are there any seniors who would like to help students in their Lit classes?

Besides grammatical concerns, business school applicants should keep in mind the following points while writing their admissions essays:

1. Write about the high school glory days.

Unless you’re right out of college, or you’ve got a great story to tell, resist using your high school experiences for the essays. What does it say about your maturity if all you can talk about is being editor of the yearbook or captain of the varsity team?

2. Submit essays that don’t answer the questions.

An essay that does no more than restate your resume frustrates the admissions committees. After reading 5,000 applications, they get irritated to see another long-winded evasive one. Don’t lose focus. Make sure your stories answer the question.

3. Fill essays with industry jargon and detail.

Many essays are burdened by business-speak and unnecessary detail. This clutters your story. Construct your essays with only enough detail about your job to frame your story and make your point. After that, put the emphasis on yourself—what you’ve accomplished and why you were successful.

4. Write about a failure that’s too personal or inconsequential.

Refrain from using breakups, divorces, and other romantic calamities as examples of failures. What may work on a confessional talk show is too personal for a b-school essay. Also, don’t relate a “failure” like getting one C in college (out of an otherwise straight-A average). It calls your perspective into question. Talk about a failure that matured your judgment or changed your outlook.

5. Reveal half-baked reasons for wanting the MBA.

Admissions officers favor applicants who have well-defined goals. Because the school’s reputation is tied to the performance of its graduates, those who know what they want are a safer investment. If b-school is just a pit stop on the great journey of life, admissions committees would prefer you make it elsewhere. However unsure you are about your future, it’s critical that you demonstrate that you have a plan.

6. Exceed the recommended word limits.

Poundage is not the measure of value here. Exceeding the recommended word limit suggests you don’t know how to follow directions, operate within constraints, organize your thoughts, or all of the above. Get to the crux of your story and make your points. You’ll find the word limits adequate.

7. Submit an application full of typos and grammatical errors.

How you present yourself on the application is as important as what you present. Although typos don’t necessarily knock you out of the running, they suggest a sloppy attitude. Poor grammar is also a problem. It distracts from the clean lines of your story and advertises poor writing skills. Present your application professionally—neatly typed and proofed for typos and grammar. And forget gimmicks like video. This isn’t America’s Funniest Home Videos.

8. Send one school an essay intended for another—or forget to change the school name when using the same essay for several applications.

Double check before you send anything out. Admissions committees are (understandably) insulted when they see another school’s name or forms.

9. Make whiny excuses for everything.

Admissions committees have heard it all—illness, marital difficulties, learning disabilities, test anxiety, bad grades, pink slips, putting oneself through school—anything and everything that has ever happened to anybody. Admissions officers have lived through these things, too. No one expects you to sail through life unscathed. What they do expect is that you own up to your shortcomings.

Avoid trite, predictable explanations. If your undergraduate experience was one long party, be honest. Discuss who you were then, and who you’ve become today. Write confidently about your weaknesses and mistakes. Whatever the problem, it’s important you show you can recover and move on.

10. Make the wrong choice of recommenders.

A top-notch application can be doomed by second-rate recommendations.

This can happen because you misjudged the recommendors’ estimation of you or you failed to give them direction and focus. As we’ve said, recommendations from political figures, your uncle’s CEO golfing buddy, and others with lifestyles of the rich and famous don’t impress (and sometimes annoy) admissions folk—unless such recommenders really know you or built the school’s library.

11. Let the recommender miss the deadline.

Make sure you give the person writing your recommendation plenty of lead time to write and send in their recommendation. Even with advance notice, a well-meaning but forgetful person can drop the ball. It’s your job to remind them of the deadlines. Do what you have to do to make sure your recommendations get there on time.

12. Be impersonal in the personal statement.

Each school has its own version of the “Use this space to tell us anything else about yourself” personal statement question. Yet many applicants avoid the word “personal” like the plague. Instead of talking about how putting themselves through school lowered their GPA, they talk about the rising cost of tuition in America. The personal statement is your chance to make yourself different from the other applicants, further show a personal side, or explain a problem. Take a chance and be genuine; admissions officers prefer sincerity to a song and dance.

13. Make too many generalizations.

Many applicants approach the essays as though they were writing a newspaper editorial. They make policy statements and deliver platitudes about life without giving any supporting examples from their own experiences. Granted, these may be the kind of hot-air essays that the application appears to ask for, and probably deserves. But admissions officers dislike essays that don’t say anything. An essay full of generalizations is a giveaway that you don’t have anything to say, don’t know what to say, or just don’t know how to say whatever it is you want to say.

14. Neglect to communicate that you’ve researched the program and that you belong there.

B-schools take enormous pride in their programs. The rankings make them even more conscious of their academic turf and differences. While all promise an MBA, they don’t all deliver it the same way. The schools have unique offerings and specialties. Applicants need to convince the committee that the school’s programs meet their needs. It’s not good enough to declare prestige as the primary reason for selecting a school (even though this is the basis for many applicants’ choice).

15. Fail to be courteous to employees in the admissions office.

No doubt, many admissions offices operate with the efficiency of sludge.

But no matter what the problem, you need to keep your frustration in check. If you become a pest or complainer, this may become part of your applicant profile. An offended office worker may share his or her ill feelings about you with the boss—that admissions officer you’ve been trying so hard to impress.

16. No gimmicks, no gambles.

Avoid tricky stuff. You want to differentiate yourself but not because you are some kind of daredevil. Don’t rhyme. Don’t write a satire or mocked-up front-page newspaper article. Gimmicky essays mostly appear contrived and, as a result, they fall flat, taking you down with them.

Have three or four people read your essay and critique it. Proofread your essay from beginning to end, then proofread it again, then proofread it some more. Read it aloud. Keep in mind, though, that the more time you spend with a piece of your own writing, the less likely you are to spot any errors. You get tunnel vision. Ask friends, boyfriends, girlfriends, professors, brothers, sisters—somebody—to read your essay and comment on it. Have friends read it. Have an English teacher read it. Have an English major read it. Have the most grammatically anal person you know read it. Hire an editor if you feel it is necessary. We don’t care. Just do whatever it takes to make sure your essay is clear, concise, candid, structurally sound, and 100 percent grammatically correct.

Always consider your audience. A big part of your overall strategy ought to be to keep in mind what it would be like to be the reader. Ultimately, you are giving a portrait of yourself in words to someone who doesn’t know you and who may never meet you, but who has the power to make a very important decision about the course of your life. It’s a real person who will read your personal statement, though—someone with real human traits who puts on her pants one leg at a time, just like you. Keep this person interested. Make this person curious. Make this person smile. Engage this person intellectually.

Depending on where you’re applying and on how prolific a writer you are, you can expect to spend anywhere from twenty-five to one hundred hours composing your stories. The process is time-consuming and maddening. Indeed, many applicants find the writing aspect of the application so unpleasant that they reach a plateau and give up. The results are mediocre, half-baked essays.

We want you to stay the full course and make every essay stand out. If you start to run out of fuel, or can’t even get started, try the following for a little octane in your writing tank: Get some free feedback. There are limits and perils to self-analysis. Call a friend or colleague for a feedback session. Ask them to recount your strengths and weaknesses. Have them list your personal and professional accomplishments. They may remind you of concrete examples and provide you with fresh insights. Chat with your references, teachers, bosses—basically anyone who knows you well.

Some specific questions you may want to ask are:

Look for inspiration. Read the essays in this book, but go and seek out articles in other places. Good examples of what a well-written personal essay looks like can be found in a number of national magazines and newspapers. In The New York Times Magazine, testimonial-like essays can be found in the vibrant “Lives” column. No one expects you to write like a New York Times columnist, but study these and you may find inspiration.

You don’t need to consult a publication as highbrow as The New York Times, though; even Reader’s Digest is full of real-life testimonials. You’ll notice how people write passionately about their experiences and what matters to them. There must be something in your life that matters to you. Make a list and return to your essays.

Let the story out. If you build it, it will come. You may have some idea of what you want to write about, but your writing skills are not up to the task. Let the content lead the way.

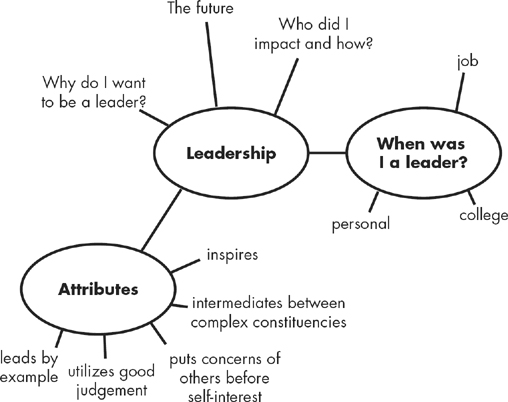

However unformed your thoughts are, just get it all down on paper. Afterward, you can prioritize and organize your points, complete half-thoughts, and delete what’s extraneous. Find the central theme and keep building upon it. If none of the above work, try clustering.

It works like this: Grab a plain piece of paper. Take a main thought or idea, and write it in the middle of the page. Then float all of your ideas around that middle concept. Write them around the perimeter of the page and make lists.

Once you’ve got a page full of your chaotic thoughts, begin to prioritize your ideas by numbering them in order of importance. Delete what is extraneous, and add whatever important information you have left out.

Now start to cluster your thoughts in terms of chronology. What should go first, then next, and so on and so forth? At the end of this exercise you should have found enough ideas and sentence fragments to compose a rough draft.

Hopefully what you’ve read here will help guide you through the process of writing a great personal essay and stand-out secondaries. Though there’s no magic recipe, we’re confident that if you follow our advice about what to put in and what to leave out, you’ll end up with a memorable personal statement that will differentiate you from the larger applicant pool and make you a more competitive candidate. Take our word for it and give it your best shot.