Bertolt Brecht wrote: “Unhappy the land that needs heroes.” Yet the Baltic states could hardly have political and cultural subjugation without consolation from folklore and literature. Heroes from old legends embodying the national fate, and those from painting, poetry and music, offered freedom and a refuge. Theatre, opera and ballet performances were packed, and writers exploited subsidies to keep national pride and independent thought alive. They fostered a climate for independence that was brought to the surface in the 1980s by rock music, which united classical composers, politicians and people in a mass gesture of defiance, which is why prime ministers can join the stage with bands today.

A wave of new experience

Artists no longer need national myths to sustain them. The freedom to travel west as well as east led to a tidal wave of influences, and those best able to handle this have often been those old enough to have experienced two very different cultural worlds. Artists struggle to balance aesthetic aspirations with the need to stay financially afloat, to secure grants, find agents to promote their work and, in theatre and film, forge co-productions with foreign participation.

Culture, happily, is not for the few. Theatres, festivals, exhibitions and concerts are well attended, and governments have realised that small countries need strong cultural initiatives to earn respect in the wider world. Baltic writers, painters, musicians, sculptors, composers and philosophers have, historically, been prime movers in public life. Being a musicologist was no bar to Vytautas Landsbergis becoming president of the newly independent Lithuania, nor was a background as a novelist anything but an asset when Lennart Meri became Estonia’s first post-war president. The former Latvian president Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga is well known as a folklorist and literature specialist, a psychologist and linguist.

Tonu Kaljuste leading the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir and the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra.

Getty Images

Roots of literature

Intellectuals and artists have nurtured the idea of independent nationhood since it emerged in the early 19th century, when the three languages began to be recorded in written form. The freedom to write and to express a national sentiment in this manner arrived in a burst of romantic novels and epic verses from which the modern culture took off. Latvian Andrējs Pumpurs told in Lāčplēsis the tale of the bear-slayer drowned in the River Daugava, who, on returning to life, will ensure the eternal freedom of his people. Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald fathered the national Estonian epic, Kalevipoeg, which ends with the hero trapped in hell but vowing to rise again and build a new Estonia.

Monument to the Estonian poet Kristjan Jaak Peterson.

Alamy

Despite a tsarist ban on printed Baltic languages, the lyrics to Pavarasario balsai (Voices of Spring, 1885), by a Lithuanian priest, perfectly encapsulated national striving and romantic sentiment. Indeed, priests, doctors and professors played a large part in establishing the region’s written cultures, first in German, then later in Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian. The Baltic peoples could boast early of high-quality European centres of learning and a fertile intellectual ambience. In Lithuania, the Jesuits created Vilnius University in 1579, and in 1632 the Swedes established a university in Tartu, southern Estonia.

Music at the top

Musical accomplishments are generally accepted in the Baltic States – even among the highest offices in the land.

At the 2008 Punk Song Festival in Rakvere, Estonia’s President Toomas Hendrik Ilves got on stage to sing the Sex Pistols’ Anarchy in the UK – he knew all the words. Later that year Latvian Prime Minister Ivars Giodmanis took over Roger Taylor’s famous Queen drum kit to play All Right Now at the Queen + Paul Rodgers concert in Rīga.

In Lithuania a former Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius is a classical music fan, and his wife, Rasa, is a violinist with the Lithuanian National Symphony Orchestra.

Rīga, meanwhile, acquired a cosmopolitan cultural importance. The East Prussian-born Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), author of the idea of folklore, was a popular young preacher at its Dom cathedral, while from 1837–8, Wagner managed the German Opera and Drama Theatre. Today, you can see the delightful Art Nouveau residence where the philosopher Isaiah Berlin (1909–97) was born.

When the Russians closed Vilnius University, between 1832 and 1905, many culturally active Lithuanians moved to Rīga, while Tartu educated Balts of all origins. Students of the 1850s included Latvian Krišjānis Barons, who collated the Latvian folk songs called dainas, and Krišjānis Valdemārs and Juris Alunāns, who founded Latvian theatre. Much Latvian effort went into overcoming perceived German colonial condescension. Budding Estonian culture was less confrontational, and many Germans teaching and studying in Tartu were fascinated with the native language and themes. But for young Estonians the birth of their nation was above all romantic. As Kristjan Jaak Peterson (1801–22), a poet and Tartu graduate living in Rīga, declared:

Why should not my country’s tongue

Soaring through the gale of song

Rising to the heights of heaven

Find its own eternity?

Peterson’s question has remained relevant to the present day. The Baltic languages are no longer oppressed, but the populations are declining, while the post-war émigré communities abroad that have striven to keep those languages alive are dwindling.

Literature led the emerging 19th-century arts, with the novel of social realism, to the fore. In Lithuania, Jonas Biliūnas described peasant life under his own name; more familiar are three assumed names, Julija Žemaite, Juozas Vaižgantas and Antanas Vienuolis. In Estonia, novelist Eduard Vilde and playwright August Kitzberg ploughed a similar furrow, while the Brothers Kaudzīte wrote the first Latvian novel, The Times of the Land Surveyors (1879).

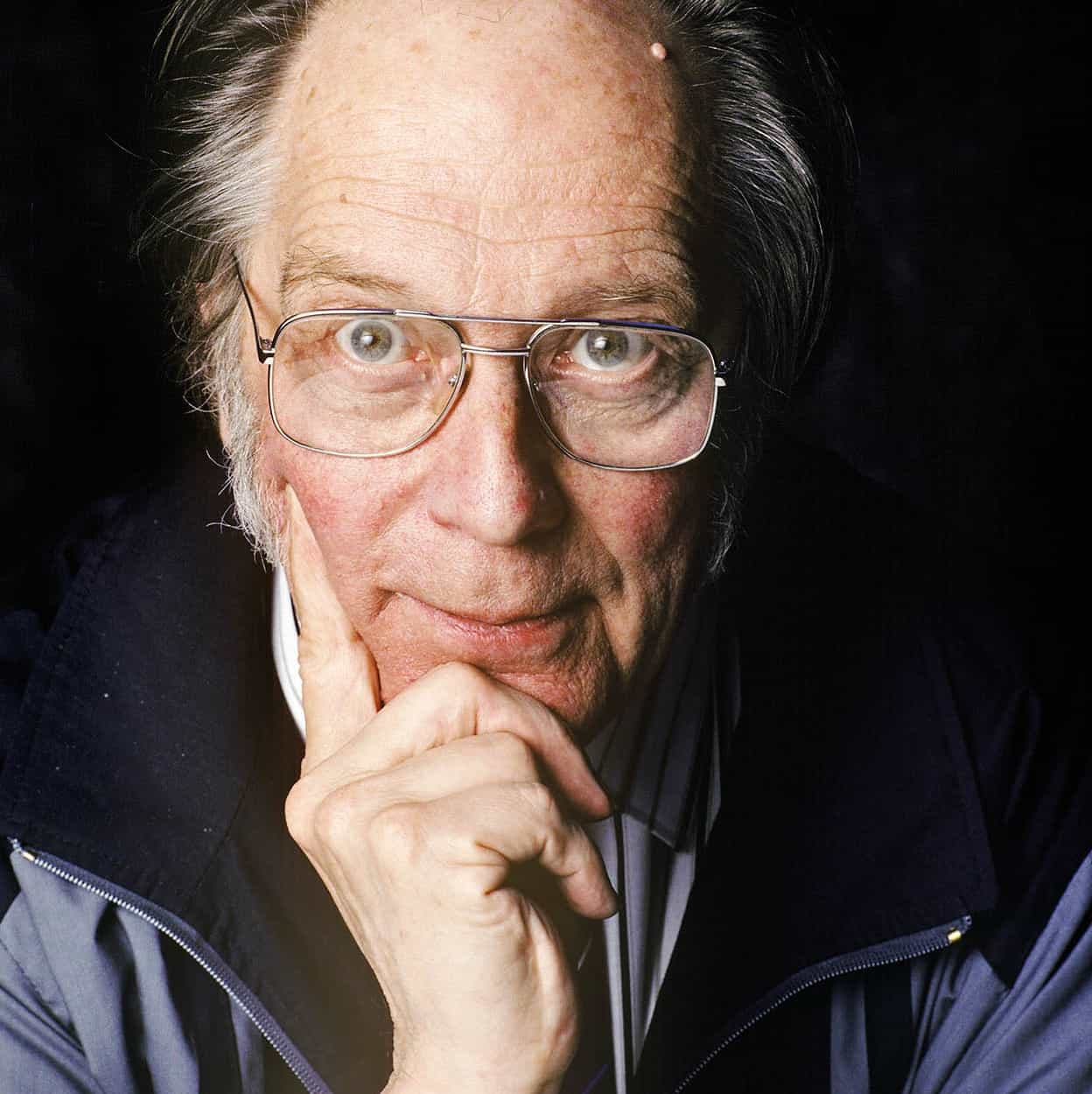

Estonian author Jaan Kross.

Getty Images

Exiled genius

Then suddenly, from Latvia, emerged a world-class talent, Jānis Pliekšāns (1865–1929), who assumed the pseudonym of Rainis. A complex, multifaceted figure, he was a lyrical poet, dramatist, translator (of Faust) and political activist. He wrote his best plays in Switzerland, where he fled after his involvement in the 1905 Revolution. Fire and Night (1905) is a dramatic statement of the Latvian spirit; The Sons of Jacob (1919), based on his own experience, deals with the conflict between art and politics. Jānis Tilbergs’ portrait of Rainis in the State Musuem of Art conveys his authority as a national elder and the personal loneliness voiced in his poetry. Modern Latvian literature still rotates around this giant figure, while his wife, Aspazija (1868–1943), a romantic poet and feminist, is also revered. Both are remembered in a museum in their Jūrmala home.

Latvian literature, always influenced by folk traditions and rustic life, was given a lyrical quality by the terse, philosophical daina. The plays of Rūdolfs Blaumanis (1863–1908) also set a high artistic standard. His folk comedy The Days of the Tailor in Silmači (1902) is still staged in the open air every midsummer.

Affected by his German education and familiarity with the German poets, Jānis Poruks (1871–1911) introduced introspection, melancholy and dreams to Latvian poetry and prose. Kārlis Skalbe (1879–1945) was dubbed the Latvian Hans Christian Andersen for his allegorical tales; he was also an exquisite poet and short-story teller.

Other notable poets include the symbolist Fricis Bārda (1880–1919), Anna Brigadere (1861–1933) and Aleksandrs Čaks (1901–50), whose Imagist style burst forth with Latvia’s 1918 independence and brushed the realities of urban life in Rīga with lyrical excitement.

Lithuanian literature did not develop such early power and variety, which may explain its greater openness to European influences. The literary group Four Winds, formed by Kazys Binkis (1893–1932), was devoted to Futurism; others imitated German Expressionism. Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius (1882–1954) was a great prose writer and dramatist whose work continued in exile. Having briefly been foreign minister, he fled in 1940, and his epic The Sons of Heaven and Earth was never finished.

The Young Estonia Movement, devoted to raising Estonian literary standards to a European level, flourished in the decade after 1905. The traveller Friedebert Tuglas (1886–1971) brought the world to Estonian readers through his romantic, exotic stories. A.H. Tammsaare (1878–1940), author of the epic Truth and Justice, was influenced by Dostoevsky, Knut Hamsun and George Bernard Shaw. He has been called the greatest Estonian prose writer of the 20th century. Find out more about the modest lifestyle of this retiring, reflective man at the tumbledown villa in Kadriorg, Tallinn, where he once lived. A more radical experimental literary group, Siuru, nurtured the poets Jaan Oks (1884–1918) and Marie Under (1883–1977). Under, who spent the Soviet period in exile, is one of Estonia’s most highly regarded poets, along with Betty Alver, whose poetry is generally darker, and whose husband was deported to Siberia.

Vytautas Landsbergis, Lithuania’s independence prime minister and a musicologist, was involved with the Fluxus Movement in the 1960s – an art movement that was joined by Yoko Ono – though he opposed the smashing of pianos.

Visual arts

Foreign influences and rural life stimulated the visual arts and music in the Baltic region. National Romanticism, imported from St Petersburg in the 1900s, ousted academic painting and influenced architecture, taking over from Art Nouveau. When that dreamy style became exhausted, new schools of national painting took over. The Baltic National Romantic style incorporates folk heroes and legends, with echoes of Munch, Beardsley, Klimt, Boecklin and Bakst.

In this vein, over Latvia’s Vilhelms Purvītis (1872–1945) and Estonia’s Konrad Mägi towers the Lithuanian mystical painter and musician Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875–1911), a Baltic William Blake. In thin, richly coloured pastels and tempera, he created symbolic landscapes suggesting a mystical universe, with motifs from Lithuanian folklore. He conceived many of his paintings as linked musical movements or as cycles of life and death, day and night. They are extraordinary, pantheistic, poetic distillations of human life. Čiurlionis’ own nature was rich and varied. He travelled widely, wrote for newspapers and almost single-handedly founded the nation’s cultural life before dying at the age of 36. His pictures can be seen, and his music heard, at his own museum in Kaunas.

Nikolai Petrovich Bogdanov-Belsky’s work.

Getty Images

After Čiurlionis, Lithuanian painting, in the hands of the Kaunas-based Ars Group, grew into a satisfyingly complex art of landscape and portraiture, well informed on European developments and characterised by a rich, dark palette. Emerald green, dark pink, mauve and a touch of yellow evolved into national colours, and a persistent motif was the inclusion of folkloric wooden figures and toys.

The first Estonian school was realist, shaped by Russian and German artistic influence. Impressionism came late, and is best seen in the works of Ants Laikmaa, Alexsander Vardi and Kondrad Mägi. Mägi co-founded the Pallas Art School in Tartu, which produced the highly individual painter Eduard Wiiralt (1898–1954), best known for his graphics, and Jaan Koort, whose deer sculpture stands at the foot of Toompea on Tallinn’s Nunne Street. By the end of the 19th century, there was a strong interest in national romanticism and quasi-mythological themes, as in the symbolist-influenced works of Kristjan Raud, who illustrated Kalevipoeg. Ado Vabbe is the greatest Estonian Modernist of the early 20th century, while noteworthy Cubists include Karin Luts and Karl Pärsimägi. Any Baltic visitor interested in painting should head for Latvia, where Vilhelms Purvītis, Janīs Rozentāls (1866–1917) and Jānis Valters (1869–1932) combined European Impressionist, Fauvist and German Expressionist tendencies with their own distinctive approach to landscape and portraiture. Their influence extended to Lithuania and to future generations of Baltic artists.

Purvītis, founder of the Rīga Art Academy, depicted the Latvian landscape, but most of his work was burnt in Jelgava during the war; Valters, who studied in Germany, painted landscapes tinged by subjective mood and represented in stark Fauvist colours; Rozentāls’ work peaks with his portraiture. Generally, the Latvian portrait tradition is outstanding. Rozentāls’ depiction of his mother and a painting of opera singer Pāvils Gruzdna by Voldemārs Zeltiņš (1879–1905), using Purvītis’ pale Latvian colours, lead into the highly coloured avant-garde movement. Artists such as Oto Skulme, Leo Svemps and Jānis Tīdemanis bring this rich period to life.

Going to Church (detail) by Janis Rozentāls.

Crabapple Archive

New cultural spaces

The 21st century has brought new art houses to the three countries. In 2006 the Estonian Art Museum Kumu, designed by the Finnish architect Pekka Vapaavuori, opened in Kadriorg Park, Tallinn, and the 1,800-seat Concert Hall opened in 2009. The National Art Gallery in Vilnius, Lithuania, reopened in 2009 after complete reconstruction. Latvia’s plans to build a new concert hall on a dam on the River Daugava in Rīga, for which a foundation stone was laid in 2010 (to be erected by 2030), and a Museum of Contemporary Art designed by Rem Koolhaas in a former power plant in Rīga’s port is scheduled to be inaugurated by late 2021, while the new national library opened in 2014.

Notable composers

Čiurlionis contributed to modern Lithuanian culture not only through painting, but through music. An intensely active year at the Leipzig Conservatoire produced works still recorded today, including the String Quartet in C minor and the first Lithuanian symphonic composition, In the Forest. To a modern ear, the symphonic work often recalls the music of Bruckner, Mahler and Sibelius, but Čiurlionis was a distinct talent in his own right. He later reworked folk songs, wrote choral pieces and organised the nation’s musical life in Vilnius.

From the First National Awakening, all the Baltic cultures developed strong traditions in choral singing. The first operas were written on national themes in the early 20th century, establishing opera as a popular but conservative genre. Baltic symphonic music evolved from the St Petersburg Conservatoire, echoing the memory of Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov. Outstanding composers of the era included Latvia’s Emīls Dārziņš, best known for his Melancholy Waltz, and Estonia’s Artur Kapp.

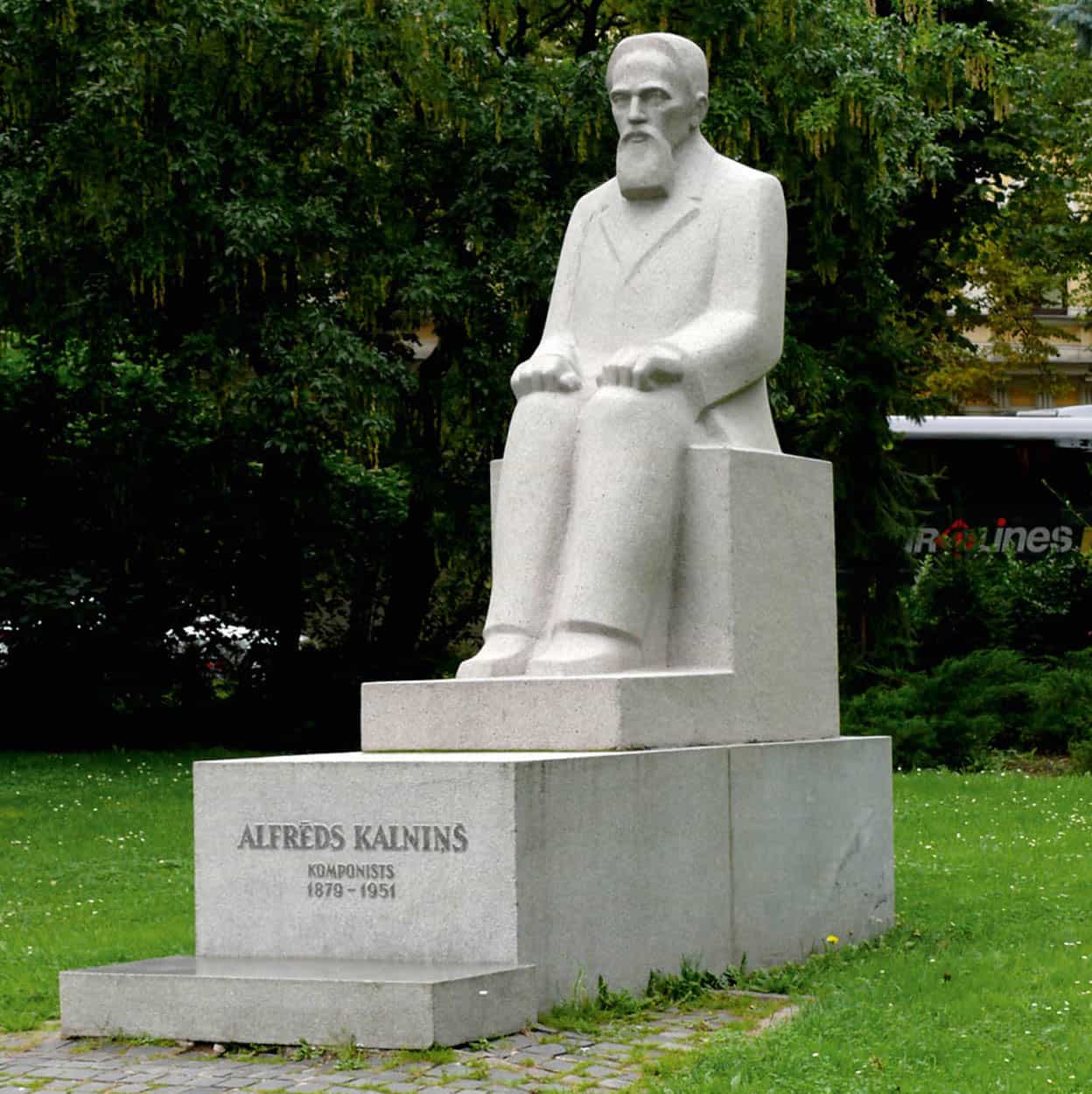

Latvians consider Alfrēds Kalniņš a musical father-figure for his varied work, both romantic and choral. His son Jānis also became a composer, later well known in Canada as John Kalniņš.

In all the arts, there was strong Scandinavian influence between the wars. An equally strong sense of alienation was felt from the Russian soul, the so-called “Asiatic principle”. In the applied arts, the Balts excelled in graphic work, textiles, book publishing and illustration.

Post-war writing

All the Baltic cultures reach out to the larger world through theatre, frequently devoting half their repertoire to world classics, with many adaptations also from prose. A strong tradition of open-air performances, with real animals on stage, persists in Latvia, alongside rather verbose poetic theatre. After the war, alien ideology and the expulsion of several key figures cramped the development of the arts. Latvians Anšlavs Eglītis, Zenta Mauriņa and Mārtiņš Zīverts, Lithuanians Antanas Vaiculaitis and Kreve, and Estonian Marie Under continued the best pre-war traditions of theatre, prose and poetry abroad. But many writers died during the war or shortly after.

A literature of suffering and displacement, recounting the mass deportations to Siberia, emerged only in the 1980s, though in 1946, The Forest of Gods, by Balys Sruoga, recounted the experience of Lithuanian intellectuals in a German camp with irony and humour. The Estonian Jaan Kross (1920–2007), who was imprisoned by the Nazis, spent nine years in Russian labour camps, and his novels and short stories provide poignant accounts of his country’s history and of the awful compromises faced by a repeatedly occupied population.

Alfrēds Kalniņš statue, Rīga.

Crabtree Archive

Soviet avant-garde

A new creative generation emerged during the Khrushchev thaw, ready to exploit the advantages of being at the fringe of a centralised empire. The Baltics became the home of the Soviet avant-garde, with productions of Beckett and Ionesco, and in Tallinn in 1969 the daring publication of Russian writer Mikhail Bulgakov’s satirical masterpiece The Master and Margherita. An uncensored edition of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four appeared in the mid-1980s. The thaw also produced notable opera singers and ballet dancers, including Mikhail Baryshnikov, from Rīga, and anti-Establishment poetry. Musicians managed to experiment with atonality and minimalism. The coincidence of modern ideas with folksong was cleverly exploited, as in the haunting compositions of Estonia’s Veljo Tormis and the ritualistic rhythms of Lithuania’s Bronius Kutavičius. The late Soviet period brought more abstractionism into painting, from Jonas Svazas and Dalia Kosciunaite in Lithuania to Latvia’s Maija Tabaka and Ado Lill and Raul Meel in Estonia.

Contemporary music

Estonian music is flourishing at home and abroad. Best known is contemporary composer Arvo Pärt, exiled in the Soviet years but now back living in Tallinn. His minimalist, sacred works includes the widely acclaimed Tabula Rasa, written for the great Latvian violinist Gidon Kremer. Other Estonians with a reputation beyond their borders are the former rock musician-turned-avant-garde composer Erki Sven Tüür and a stream of world-class conductors, among them Neeme Järvi and his son, Paavo. The Latvian conductors Mariss Jansons and Andris Nelsons have made their names with, respectively, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam and the City of Birmingham Orchestra. Lithuanian modernist Osvaldas Balakauskas also enjoys world renown, having earned the title of “Lithuanian Messiaen.”

Performing arts

Lithuanian theatre, currently favouring radical takes on the classics, has generated several world-class producers, among them Jonas Vaitkus, Juozas Nekročius and Oskaras Korčunovas. Lithuanian dramatist Marius Ivaskevicius and Estonia’s Andrus Kivirähk both delight in poking fun at national identity, while Adolfs Žapiro and Pēteris Petersons are two very active, cosmopolitan figures in Latvian theatre. The National Opera in Rīga is the most dynamic in the Baltic States, and contemporary dance now has a dedicated following in all three countries.

Film and video

Estonia has a particularly strong tradition in animated film, with directors such as Priit Pärn scooping prizes at international festivals. Other popular Estonian directors include Veiko Õunpuu, Jaak Kilmi and Toomas Hussar. Latvia’s best-known film director is Laila Pakalniņa, whose work has been screened at Venice and Cannes. Latvia is also renowned for documentaries, a form championed by award-winning directors Ivars Seleckis and Herz Frank. Lithuania’s best-known film director is Sarunas Bartas, whose philosophical and minimalist films have won international acclaim. The widely popular action comedy Redirected, which was written and directed by Lithuanian Emilis Vėlyvis, was a hit in 2014, screened in the UK and at many international film festivals. Bigger-budget historical films about the post-1917 fight for independence, the collapse of the first republics and post-war resistance are popular in all three nations.

“When the musicians saw the score of Tabula Rasa, they cried out: ‘Where’s the music?’ But then they went on to play it very well. It was beautiful. It was quiet and beautiful.” Arvo Pärt

Vilnius is home to the excellent Contemporary Art Centre, which has a reputation for being one of the most dynamic and innovative of its kind in the Nordic area, hosting the Baltic Triennial in 2009, when Vilnius was the European Capital of Culture.

From the 2007 Latvian film, Defenders Of Riga.

Kobal

In all three countries, video art has taken over from painting. Estonia’s Raoul Kurvitz and Jaan Toomik and Lithuania’s Deimantas Narkevičius have all contributed to the Venice Biennale. In Lithuania there has been particular focus on social issues and questions of female identity, as in a video by Egle Rakauskaite, which investigates the experience of eastern Europeans working in the United States.

Filmmakers are making their mark, too, not least because the three countries provide exceptional backdrops. The unspoilt towns and countryside are ideal for period dramas. The Rīga Film Fund was established in 2010, and shortly afterwards shooting in the city began in a joint venture between Latvia’s Film Angels Studio and Indian Bollywood filmmakers Illuminati Films.

In the Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius.

Alamy

Modern literature

Popular present-day writers include Latvian poet and writer Imants Ziedonis and prose-writer Zigmunds Skujiņš. Writers who were censored and repressed during the Soviet era and who have since won wide acclaim include Latvian poet and writer Vizma Belševica, poet Knuts Skujenieks and Lithuania’s Juozas Aputis. Traditionally dubbed “land of poetry”, prose and innovative essay-writing is now flourishing in Lithuania. The novels of Lithuanians Vytautas Bubnys and Vytautas Martinkus, though very different, show the continuing attraction of folk themes. Members of the younger generation of writers include Renata Šerelytė, author of short stories, award-winning novels and poetry, as well as Kristina Sabaliauskaite, mostly known for her bestselling historical trilogy Silva Rerum. Critics in Latvia have spoken of the “rebirth of the short story”, a form championed by writers Andra Neiburga, Jānis Ezeriņš and Nora Ikstena. Estonia’s Jaan Kross and the poet Jaan Kaplinski have an international following and have both been nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature.

Moving on from explorations of the Soviet era, writers such as Estonia’s Tõnu Õnnepalu’s, whose Border State explores the experience of a young homosexual in Paris, examine contemporary life and adopt more experimental styles thanks to exposure to Western trends. Another good example of this trend are Kristiina Ehin’s poems from her book The Scent of Your Shadow, which make for a perfect introduction to the Estonian way of life. The controversial Kaur Kender, often compared to Irvine Welsh, is yet another contemporary Estonian writer worth reading. His bestseller Petty God brutally explores the vulnerabilities of the modern society. Similarly, Lithuania’s Jurga Ivanauskaite has tackled in ironic and provocative fashion contemporary issues such as consumerism, advertising and the dumbing down of culture, while also exploring Buddhism following travels in Tibet. A mystic tendency in Lithuanian literature contrasts with a strong, continuing cult of the grotesque, the absurd and magic realism in Estonia.

Spreading the word

Inevitably, Baltic literature suffers from a dearth of translation into foreign languages, although extracts are regularly published by the countries’ literature centres and cultural institutes, which will happily inform the curious about the latest trends in the arts.