I got Pac-Man Fever

I’m going out of my mind.

—Buckner & Garcia, “Pac-Man Fever”1

Pac-Man Fever was the Beatlemania of Generation X. The first video game to fully permeate North American popular culture, Pac-Man stood for the medium itself at the moment when video games became enshrined as a mainstream form of leisure. In the early 1980s, Pac-Man was the most successful game commercially and the most popular game with the widest range of players: boys and girls and children and adults, though kids were the main consumers of games like Pac-Man. It inspired an enormous array of spinoffs, adaptations, and merchandise bearing the iconic yellow circle with a missing wedge and a black dot for an eye. It is impossible to imagine the emergence of the medium without Pac-Man. Along with a handful of other games like Pong, Space Invaders, Tetris, and Angry Birds, Pac-Man is a game that everyone seems to know and appreciate—a classic. Sherry Turkle called it “the first game to be acknowledged as part of the national culture.”2 Pac-Man is like a perfect pop song: it seems so simple, so catchy, so universal in its appeal. No game more strongly defines the first decade of the medium.

This is remarkable for several reasons. Pac-Man was unlike most games in its aesthetics and representation. It has a simple interface—just the four-way directional joystick—and a novel concept in which you navigate a maze, eating dots or monsters to collect points and graduate to the next level. The images of the yellow Pac-Man and brightly colored ghosts were light-hearted at a time when most games had imagery deriving from science fiction or war. Many of the popular games at the moment of Pac-Man’s initial popularity were about shooting or driving (in some games like Tron, you would get to do both) and had militarized space adventure scenarios. In distinction to the electronic zapping, blasting, bombing warfare noises of games like Asteroids, Galaxian, Tempest, and Zaxxon, a game of Pac-Man starts off with a cheerful, funky four-bar intro in a major key. As you move around the maze, the game plays an uptempo waka-waka rhythm to accompany the yellow figure’s munching. The Pac-Man is animated to open and close his mouth perpetually, a ravenous sprite. When you lose in Pac-Man, the music is a descending glissando pitying you upon your demise as the yellow figure vanishes. The game is an amusing cartoon, not an intense space opera. Pac-Man is a friendly character of the kind found in comic books and Saturday morning television for young children, not a spaceship in battle over the fate of the universe. The Pac-Man arcade cabinet art pictures a rotund comic book figure with enormous eyes and frog feet. It’s goofy, not tough or adventuresome. The hit spinoff Ms. Pac-Man (1982) interpolates snippets of romantic comedy between its levels, showing Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man progressing from their “meet cute” to reproduction.

The most notable commercial success in video games before Pac-Man was Space Invaders. Space Invaders was the first massively popular shooter game. It picks up on several traditions of representation and amusement: sci-fi alien invasion narratives like War of the Worlds (it was inspired by the 1953 film adaptation) and electro-mechanical shooting gallery rifle games from the penny arcades and sportlands. In Space Invaders, you are defending civilization from assault by killing the enemy. It was no coincidence that Space Invaders’ popularity coincided with the dominant presence in popular culture of Star Wars, in which warfare in a distant galaxy plays into boy-culture ideals of courage in battle against a mortal enemy. Many other versions of this scenario were successful as video games, including Missile Command, with its Cold War dystopia of nuclear conflict, and Galaxian and Galaga, which update Space Invaders with color graphics and other technical innovations. Asteroids, Defender, Tempest, and many other space battle games worked in similar ways by tapping into masculine fantasies of power and heroism.

Like any video game of this period worthy of sustained attention, Pac-Man had considerable complexity and scaffolding levels of difficulty.3 To master it was no easy feat, and its challenge inspired competitive, intensive play among the denizens of the arcade and, eventually, home video game players. Pac-Man is a chase game with a twist: you, as the Pac-Man, are evading your enemies, the brightly colored ghosts Blinky (red), Pinky (pink), Inky (cyan), and Clyde (orange), while trying to eat all 240 of the pellets in the maze (collecting points as you consume them), until you swallow one of four larger power-pellets also known as energizers, one in each corner of the maze, which effects a dramatic reversal. All of the ghosts turn royal blue and are transformed from lethal to vulnerable. The monsters reverse direction while you attempt to chase and consume them before they revert to their usual red, pink, cyan, or orange. For this brief time, the hero and the enemies trade roles of prey and predator. But if you try to eat a blue ghost at the moment it is changing back, you die, so one critical element of the game is timing your attack and knowing when to retreat.

Pac-Man’s gameplay involves evasion and pursuit, a race against time, and navigation of a maze, often applying a strategic pattern to guide your route. Each of the four ghosts is programmed to move in its own pattern, which a skilled player can come to appreciate and predict. (Many guidebooks offered instruction on maze pattern strategy, and players standing around Pac-Man cabinets learned patterns from one another.) After clearing a board of all the dots big and small, a fresh maze appears and the challenge increases. The boards are named for a colorful fruit (and on later levels, a galaxian, bell, or key) that appears periodically in the center, which can be eaten for points—the later levels have more valuable fruit. On more advanced levels, Pac-Man moves faster; on even more advanced levels he slows back down, though the enemy ghosts do not. On higher levels, ghosts are blue for a shorter time after you eat a power-pellet, making it harder to eat them. Eventually they stop being blue at all. At 10,000 points you earn an extra man, but if you die three times (the extra is a fourth) your game is over and you have to drop another quarter in the slot.

Pac-Man works exceptionally well as a game, rewarding both casual attempts and devoted, repeated play. It is fun on the first quarter and the hundredth.4 When you die, you are likely to want to try again. It has many appeals: colorful characters and fruit, humorous sounds, an easy interface, a novel concept (at least in the early ’80s), and the serious challenge of mastering its increasingly difficult levels. It is not surprising that Pac-Man became popular, but it is quite notable that the one game that reached its unparalleled status was unlike most video games in some important ways. Pac-Man and its various spinoffs and adaptations were never as masculinized as Space Invaders and those games influenced by it. Pac-Man had a more inclusive, egalitarian quality that opened video games to more players and softened the medium’s reputation as aggressive and violent. Pac-Man was instrumental in making video games a mass phenomenon, and its value to the games industry and also to the culture of electronic play was in its expansion of the market beyond the young and male crowd. Video games became mainstream entertainment and a pop culture craze at the moment when Pac-Man made them seem safe and inviting for all.

When Pac-Man was released in 1980 by Namco, a Japanese firm, video games had become well established as a profitable industry and a popular form of public and private amusement, but it was clear to all involved in the video games trade that young and male players were their main customers. Pac-Man was designed to increase the market size for video games by appealing to women in particular, drawing them into the game rooms that had in some ways seemed forbidding to female players or to opposite-sex couples. Appealing to women had several virtues for game manufacturers, operators, and arcade proprietors. It not only expanded their customer base, but also brought a measure of respectability to the business and medium of video games. A greater gender balance in arcades and other venues of public coin-op play would have the potential to change their reputation. Women or teenage girls were also regarded as a potential magnet for male customers, under the assumption that boys would follow where the girls are. While it may not have been anyone’s intention to make a more child-friendly game, Pac-Man also had the virtue of being cute and cartoonish rather than aggressive and violent just at the time when games were a cause for concern because of their focus on shooting and killing enemies. Pac-Man would seem less likely than the space and war games to be corrupting the youth.

Toru Iwatani, the young designer who created Pac-Man for Namco, has spoken repeatedly of his inspiration in making a game to appeal to women. The popular games at the time were all about shooting aliens, which was not perceived to be a theme that appealed to female players. In order to get women and couples into game rooms, Iwatani designed Pac-Man to have a specifically feminine draw: “When you think about things women like, you think about fashion, or fortune-telling, or food or dating boyfriends. So I decided to theme the game around ‘eating’—after eating dinner, women like to have dessert.” He has often compared the form of Pac-Man to a pie with a missing wedge: “If you take a pizza and remove one piece, it looks like a mouth. That’s where my idea came from.” The ghosts were inspired not by the sci-fi or space opera tropes of most popular games, but from anime and manga along with American children’s comics and cartoons. The ghosts were like Casper or Obake no Q-Taro. Powering up the Pac-Man by eating an energizer pill was inspired by Popeye eating his spinach to gain the strength to defeat his foe Bluto. In Japan, the game was not initially terribly popular, but it appealed, according to Iwatani, to “people who didn’t play games on a daily basis—women, children, the elderly.”5 As Tristan Donovan observes in his history of video games, Pac-Man draws on the Japanese concept of kawaii, often translated as cuteness, typified in global popular culture by Hello Kitty.6 Many observers both in the ’80s and later on identified cuteness as one of Pac-Man’s key appeals, and cuteness has never been aligned with the dominant sensibility of teenage and young adult masculinity in the United States.7

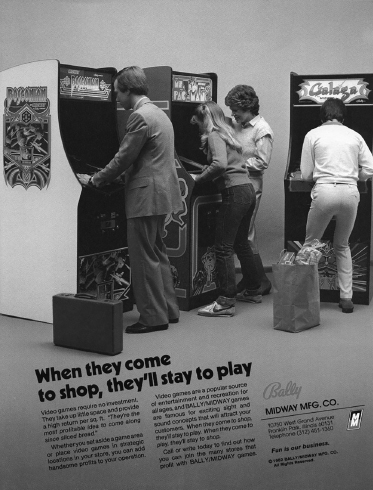

The name Pac-Man comes from the Japanese puku-puku, an onomatopoeia that references the sound of a mouth opening and closing. It is named for the act of incessant eating. Originally in Japan the game was named Puck-Man but when Midway licensed the game to release it in the United States, it changed the name to Pac-Man to avoid any vulgar vandalism. Upon its release stateside in October 1980, the game exceeded expectations. In Japan, it had been less popular than the contemporary Namco game Galaxian, the variation on Space Invaders. But in North America, Pac-Man appealed widely to children and women in addition to male players, and to both more casual and more serious visitors to arcades.8 Its financial impact was staggering: it earned $1 billion in revenue in its first fifteen months in the United States, and the home console version was predicted in the pages of Time to be a bigger money-maker than Star Wars, a widely recycled factoid.9 America had almost 100,000 Pac-Man arcade cabinets collecting quarters in 1981, and soon enough more than two million Pac-Man game cartridges would be sold to consumers with Atari consoles at home.10 The release of this ultimately disappointing product, which sold well but was widely regarded as a pale imitation of the arcade version, was promoted by a massive marketing stunt called National Pac-Man Day on April 3, 1982, with public events staged at malls and other public places in many American cities.11 Pac-Man merchandise from apparel and lunchboxes to wristwatches and drinking glasses was for sale in every department store and souvenir shop. The 1982 World’s Fair, in Knoxville, Tennessee, had not only several game rooms filled with video arcade cabinets, but four Pac-Man souvenir shops selling shirts, mugs, pins, posters, pillows, stickers, Pac-Man Putty, miniature souvenir license plates, tote bags, and a child-size sleeping bag.12 There were various Pac-Man spinoffs and adaptations, including a tabletop Coleco game, a Bally pinball game, and most famously the feminized version of the game hailing the interest of girls and women, Ms. Pac-Man, which debuted in January 1982 and became hugely profitable in its own right. Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man’s unprecedented success were routinely attributed to their ability to get women to overcome whatever reluctance or hostility they had to playing coin-operated video games.

Popular press stories often highlighted the female participation invited by Pac-Man. An NBC News report on May 25, 1982, on Pac-Man Fever noted not only the game’s outstanding commercial fortunes, but also its unusual demographic appeal. An interview with Michael Blecha, a “Pac-Man Retailer” framed against a wall of Atari cartridges, offered this observation: “Women are insane about this game. Men like the sports games, the action games and the space games. Women like the predator games.” The report continued by showing images of a store selling Pac-Man products including T-shirts, coffee mugs, beer mugs, tote bags, pillows, balloons, hats, board games, books, dolls, hand puppets, and neckties. Pac-Man was a mass market bonanza, a Mickey Mouse for the electronic age. The report concluded with a shot of hands counting money. In the pages of the November 1982 issue of Working Woman magazine, the success of Pac-Man was attributed to “the huge numbers of women who play.” In drawing the familiar distinction between Pac-Man and war games, the author framed video games pre-Pac-Man as an exclusionary medium in which men played and women watched. Pac-Man liberated women from their place by the sidelines. Working Woman explained the appeal of Pac-Man as one of genre distinction: “Video experts believe that Pac-Man’s lighthearted graphics, catchy tunes and the absence of exploding spaceships attract women players.”13

A first-person column in New York magazine in 1983 by Jennifer Allen chronicled her descent into Pac-Man addiction, a fix she satisfied at a coin laundry on the Upper West Side of Manhattan where other players around the machines were “skinny and black and … about fourteen years old.” By contrast, she felt “like the chaperone at the party.” Pac-Man became her game upon her first encounter with it at a Catskills resort game room. In contrast to the players at the space/shooting games, the ones who preferred Pac-Man, adults and children alike, were “laughing and talking, better tempered than the dour, determined players who wrestled with Asteroids and Space Invaders.” This more sociable interest in play would put distance between Pac-Man and the more aggressive and violent arcade games, which the writer implied endeared Pac-Man to female players. “There were no explosions or smashups; when a Pac-Man got eaten, the only sound was a droopy, wilting noise, the kind that might accompany a clown making a sad face.”14 The news interest of this story, which appeared in 1983, would have been not just the topicality of the video games craze and of Pac-Man Fever as an emblem of all that, but also the man-bites-dog quality of a grown woman being a serious player of video games.

All of this newfound feminine appeal occurred just at the moment of media panic around video arcades, just as moral authorities and guardians of virtue agitated for regulation of game rooms and video game cabinets in the name of protecting youth from this fresh danger. One reason why Pac-Man and its many spinoffs were so welcome in game rooms, stores, and the many other spaces of play was that girls and women were regarded so favorably by proprietors of these venues. Unlike male patrons, girls and women were not often seen as corrupting or threatening influences. On the contrary, their presence was reassuring of the wholesomeness of a space and of the activities going on within. According to one study of young people’s attitudes about games and arcades, some female patrons worried that their presence in game rooms filled with pinball and video machines was somehow improper, but changing the image of games could change this perception. The campaign in the coin-op trade to increase female patronage was good business not just in the sense of attracting more customers, but also in the sense of remaking the image of coin-operated amusements as legitimate and culturally worthwhile.15

By appealing too much to “loners” and “losers,” the coin-op trade risked its reputation. In a polemical column in a January 1982 issue of the coin-op trade paper PlayMeter, Marion Cutler and Jane Petersson argued that this reputation was critical to the fortunes of the whole industry, and that “distaff fans” of video games were crucial to turning things around: “Women—more than zaps, lights, or electronics—are the signal that the game has become respectable.” They made an impassioned case that the taverns, arcades, and other spaces of electronic play had been inhospitable to female patrons not just because they were shady or dusty or unsafe, but also because the games themselves were a big turn-off: “With half-naked female figures and gigantic ‘zooms’ and ‘zaps’ forming the backgrounds, pinball and electronic games and their surroundings fairly shriek ‘Men Only!’”16

The imperative to get women into arcades could be accomplished by recognizing their newfound social and economic mobility in the wake of second-wave feminism. The coin-op trade could capitalize on women’s expectations of equality and their increased spending power by offering experiences of leisure and play hospitable and desirable to them. If women expected to be treated as equals and to have opportunities to enter any realm open to men, they would naturally find their place in arcades and game rooms. But this might necessitate catering to them to win this business. It might be particularly appealing, Cutler and Petersson argued, if the spaces of play could become sites of courtship—pickup or date spots. The appealing scenario they offered PlayMeter readers, typically men in the amusements trade, was that upwardly mobile women would begin to patronize their businesses as not only an expression of their equality with men, but also as a way of meeting eligible bachelors. In the early 1980s, when girls and women were discussed as potential patrons spending money on video games, ideas about romance and courtship were often part of the story.

The way to get women into arcades was most often by offering the kinds of games they were believed to prefer, and games with cute or cartoony themes were most closely identified with female players. In addition to Pac-Man, this category would include Donkey Kong, Frogger, and Centipede (a rare early game to have been designed by a woman), though Centipede was also a shooting game in the Space Invaders style. In explaining “The Video Games Women Play … And Why” in the May 1, 1982, issue of PlayMeter, Mary Claire Blakeman made clear not only that such “games where you can recognize things” were a positive appeal, but also that games of “the space wars genre” were a turnoff because of their association going back several decades with astronauts and science-fiction movie heroes who were always male. A businesswoman in Oakland offered that she prefers “games where you can enjoy the graphics even if you lose.” On the other hand, she did not favor “the space games where things are coming at you out of nowhere.” Pac-Man was singled out as a particular favorite, and the author’s identity as a woman was front and center in this perhaps tongue-in-cheek evaluation:

I don’t care what the socio-political experts say—I like Pac-Man because it’s the only game where you can eat your way out of your troubles. Not only that, but the more you eat the better you are. What a nice antidote to all those diet books, aerobic dance classes, and medflies in the pantry. In Pac-Man it’s simply—the more you eat, the more you win.17

But beyond its content, Pac-Man was also celebrated for its simplicity and ease of play, and for its sense of fun. It demanded less dexterity and devotion than some games, which made it more inviting for casual players. Pac-Man was also a game well suited to courtship by being less gender specific and masculine, more neutral. A boy might like to show a girl how to play, or to impress her by achieving a high score similar to his feats at a carnival game winning her a prize.18

In the publications aimed at fans of video games, which exploded in number in 1982 and 1983, we find not only the assumption that video games were especially for a subculture of boys and young men, who are the implied reader except in rare instances of broader address, but also that Pac-Man went against the grain, becoming more popular than any other game through its mass popularity, which exceeded subcultural bounds. One of several guidebooks published at this time with the title How to Win at Video Games rated a number of popular arcade games by their “sex appeal” (meaning the ratio of male to female players). Defender was rated 95 percent male. Asteroids, “stereotypically, a male game,” was rated 60 percent male. Donkey Kong and Centipede were both rated 50–50 male–female, and of the latter the author wrote, “Cuteness overcomes most people’s squeamishness about bugs.” Only Pac-Man was given a ratio favoring female players, 60–40, with a note that its “strong appeal to women [is] accredited to its non-violent theme.”19

Often these books and magazines tried to explain Pac-Man’s amazing ubiquity, its status as the number one game by far. “One of the big reasons for Pac-Man’s popularity,” asserted another 1982 volume simply called Video Games,

is that girls like him just as much as boys. Before Pac-Man, arcades were mostly for boys who liked to play the space zap games. A lot of people thought that would never change. Even arcade owners were surprised when girls started showing up to play Pac-Man. Of course, girls’ interest in video games wasn’t caused just by Pac-Man. Video games had spread to restaurants, airports, supermarkets, convenience stores—places that weren’t strictly boys’ territory—and the girls started to play them.20

The popularity of Pac-Man was also explained by reference to the game’s simplicity and cuteness and its “very human, very personal” graphics.21

The bimonthly magazine Vidiot, published by Creem magazine in 1982 and 1983, celebrated Pac-Man as the first “computer-generated pop star” by emphasizing his cuteness and simplicity as the way to economic good fortune for the games industry. Pac-Man was “the first electro-terrestrial with personality,” “the Beatles of his day.”22 But Vidiot also referenced Pac-Man’s amazing popularity as a product of crass hypercommercialism, which it surely was. A headline on the February–March issue of 1983 screamed “Pac-Man Sells Out!” The unflattering association between consumer culture and femininity fit with Vidiot’s convergent topics of rock music and video games, with its frequent photos showing mostly male rock stars posing by video games with captions like “The Rockets are Vidiots!” In a roundup of Pac-Man merchandising, which is supposed to have earned $10 million “this year,” the magazine presents snarky put-downs of products for sale in stores including fruit-scented erasers, ball darts, rearview mirror hang-ups (ghosts in place of fuzzy dice), punch balls, pillows, shower curtains, things you stick on the end of a pen, bumper stickers, board games, thermal underwear, lunchboxes, puppets, and shoelaces. The final entry describes a cigarette lighter imprinted with the Pac-Man logo, for which the author recommends the following use: “Take all the Pac-Man merchandise you can find, arrange it neatly in a heap and apply this product.”23 In a box alongside this write-up ran a review of the new ABC TV series from Hanna-Barbera, referenced as The Pac-Man Cartoon Show, treated as a curiosity but a dull and predictable one.24 The popularity of Pac-Man might have demonstrated that video games were now part of the national culture, but it also came at the expense of the subcultural cohesiveness of serious video game players (the type implied in the address of fan publications like Vidiot). Their defensiveness about the commercialism around Pac-Man was not expressed in overtly gendered terms, but the contrast between a young, male subcultural identification and this mass market schlock is an undercurrent in fan discourse, especially considering how regularly Pac-Man’s identity was as the one video game women really like.

This identity is underlined in another ironic fan publication, Mark Baker’s satirical book I Hate Vidiots, published in 1982. In a combination of the style of The Official Preppy Handbook (1980), with its brief sections and lists and drawn illustrations, and the irreverent satire of Mad magazine, I Hate Vidiots skewered video game culture at the moment of its ascent. It travestied the players of video games by including a chapter titled “Psychological Profiles of the Vidiot by Game,” using the male pronoun in its descriptions of each game’s player profile. Of Missile Command’s player, Baker writes: “He looks at life through the window of vulnerability.”25 Of the Defender player: “This vidiot would seem to have a lot of things going for him: manual dexterity, mental agility, and especially a self-sacrificing nature.”26 And for the player of Tempest: “If he weren’t addicted to Tempest, he’d probably be an acid-head anyway.”27

But Pac-Man is different, and the appeal to women is taken here as an opportunity to sexualize video games, and both the male and female players who enjoy them, in terms of gendered desire and pleasure. This sexualizing rhetoric follows many representations of girls or women and video games, such as the assumption that the presence of girls means that arcades become sites of courtship, or the frequent inclusion of shots of women in fan magazines like Vidiot modeling T-shirts or promoting subscriptions, similar to the use of posed models by motorcycles and hot rods. So in I Hate Vidiots, the appeal of Pac-Man to female players becomes an opportunity to stereotype sexual difference:

Pac-Man is a video addiction preferred by female Vidiots (so right away, you know there is something funny about a guy who plays this game). Women don’t like video games because they’re all about little guns and missiles, shooting, firing fingers on buttons, thrusting, battering, penetrating, explosions throbbing, pulsating, the earth moving in a final shudder of … Ahem, well, girls don’t really like them.

Pac-Man is different. Pac-Man provides a thrill that the female Vidiot can enjoy. It’s all about playing coy, running, hiding, waiting until the little guys almost get you cornered, then turning suddenly to pounce like Cat Woman, eating, engulfing, swallowing, scratching, clawing, churning, engorging, devouring, throbbing, pulsating, the earth moving in a final shudder of … Whew! It is getting hot in here, or is it just me?

Pac-Maniacs are Vidiots who never get called for dates. They just go down to the arcades to snicker at the dopey guys down there. They use their reflection in the screen to put on their makeup. And they’ll never get a date either, if they don’t stop hanging around in the corner of the arcade giggling with the other girl Vidiots.

Famous Pac-Man Vidiots: Britt Ekland, Linda Lovelace, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote.28

By including two female actresses, one a Swedish movie star and sex symbol and the other famous for appearing in Deep Throat and other porn films, along with two famous gay male writers, as the “Pac-Man Vidiots,” Baker underlined and stigmatized the sexual difference meant to characterize the one video game not identified with straight, young, male players. The illustration accompanying this psychological profile was of an attractive woman in repose on a bed under a blanket pulled up to cover her chest, with a Pac-Man arcade cabinet in the bed beside her, and both of them smoking postcoital cigarettes.

Figure 6.2 Illustration from Martin Barker, I Hate Vidiots, sexualizing Pac-Man and its female players.

This emphasis on eroticizing Pac-Man and its players was carried along into the release of the game’s most successful arcade sequel, Ms. Pac-Man, in 1982. Many copycat games attempted to capitalize on the munching maze concept, including K. C. Munchkin, a game cartridge for the Odyssey2 console removed from the market in 1982 after Magnavox lost a copyright infringement case.29 Ms. Pac-Man’s origins were in Bally Midway’s efforts to release a homegrown version of its own smash success as the company licensing Namco’s import. Crazy Otto, a copycat maze game created by an American company called General Computer Corporation (GCC), became Ms. Pac-Man when Bally Midway acquired it and changed the name and some small details of character design. Crazy Otto/Ms. Pac-Man was in some ways an improvement on Pac-Man. While the basic design—the maze, the dots, the ghosts, the joystick—remained the same, the newer game had four different maze configurations of increasing difficulty, and the patterning of ghost movement was more challenging. In place of stationary fruit, the new game’s fruit floated through the maze, adding the challenge of another element of pursuit. Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man were quite similar, but the latter seemed like an evolutionary step forward, and its popularity extended and amplified the influence of Pac-Man.

The animations in between levels of Ms. Pac-Man also subtly built on the branding of the franchise. Even as Crazy Otto, the game had animations functioning as intermissions between mazes (Pac-Man had these too), each one introduced with a clapperboard conveying that these are little cinematic narratives. Originally these intermissions used the sprites of the Crazy Otto characters but when the game was made over as Ms. Pac-Man, they were changed to suit the theme. In the first movie, “Act 1: They Meet,” following the second board, the courtship of Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man occurs during their pursuit by two different ghosts. The hero and heroine find each other during their comical evasion of the bad guys, and at the end they run off together. After the fifth board comes “Act 2: The Chase,” against an electronic rendition of a cheerful ragtime tune suitable for silent movie accompaniment. This movie is an homage to the chase scenes of early cinema. Alternately the girl pursues the boy across the screen and vice versa; their chases speed up, and the brief segment ends without resolution, a cliffhanger. Finally comes “Act 3: Junior” after the player has cleared seven boards. Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man are pictured together at the bottom of the screen as a stork flies in and drops a bundle that lands by the two characters: inside is a baby Pac-Man. According to Doug Macrae, who worked on the game for GCC, the name Ms. Pac-Man was chosen over Miss or Mrs. not as a gesture toward women’s liberation but rather to avoid any suggestion that the offspring arriving in Act 3 of the game’s intermission movies has been born out of wedlock.30 In the cartoon adaptation on TV, Pac-Man, which ran for two seasons between 1982 and 1983, the Pac family includes a wife, Pepper, and a baby. Pepper has a stereotypical female role as wife and mother rather than as protagonist leading the efforts against the evil ghosts. The family scenario carries over from the arcade game to this spinoff.

The decision for Bally Midway’s sequel to have a female character was seen straightforwardly as an effort to capitalize on the popularity of Pac-Man with female players. Electronic Games magazine told fans that “Midway wanted to thank the scores of female arcaders who took Paccy to their hearts by producing a female version of the coin-op classic.”31 Bally/Midway promoted Ms. Pac-Man as the “femme fatale of the game world,” and the character and arcade cabinet design emphasized femininity while maintaining the cute and cartoonish style of the original. In a Bally Midway flyer (an advertisement aimed at arcade game operators), a Ms. Pac-Man is played by a teenage girl in jeans and sneakers with long blonde hair while a boy looks on with excitement. On either side, grown men play video games with space/shooting themes: a Bosconian and a Galaga.32

Figure 6.3 1982 Bally/Midway flyer showing Ms. Pac-Man and its intended market.

On the screen, Ms. Pac-Man looks the same as Pac-Man except for her red lips, red hair ribbon, and the addition of an eye and a beauty mark. (Pac-Man was often represented with a black dot for an eye, but not in the arcade game itself.) On the cabinet and marquee, Ms. Pac-Man is certainly girly. On the marquee (the glass-covered signage above the screen), yellow type is outlined in pink and all of the graphic elements are set within a yellow-outlined pink rectangle with rounded corners against a light blue background. Ms. Pac-Man wears blue pumps and heavy makeup: big pink lips pursed as if to kiss, brightly blushed cheeks, long lashes, and eyelids covered with blue eye shadow. She sits in the valley formed atop the letter M in a glamor pinup pose, one hand behind her head and both knees raised. The menacing, masculinized ghost is pink too and he leers at her. The side of the cabinet, less often seen when arcades position games lined up along a wall, repeats the same color and graphical motifs, but including the ghost’s pursuit of Ms. Pac-Man, who is running away on her high heels while now wearing large pink gloves.

Figure 6.4 Ms. Pac-Man marquee with its feminized representation of the character and the game.

Many publications picked up on the female audience intended for Ms. Pac-Man and its effort to capitalize on the broadening of video games’ demographics that Pac-Man represented. The female version was often referenced in highly gendered terms in a way that Pac-Man certainly never had been. She was a “buxom goblette” and a “sleazy lady” who likes to eat and pop pills.33 The fan magazine Blip described her eyelids as “fluttering,” and claimed that when caught by a ghost, Ms. Pac-Man “faints instead of deflating.”34 These are perhaps instances of stretching to find descriptive terms for games that, ten years into the commercial life of the medium, were still fairly abstract in their representation and quite primitive in their character design. But they also look like opportunities to circumscribe female representation by making it different from the norm, and by emphasizing that female identity be evaluated in terms of appearance and sex appeal, even when we’re talking about something as simplistic and unsexy as a Pac-Man with lips and a hair bow.

Whatever the impact of this gendered discourse at the time, Ms. Pac-Man, like Pac-Man, became a favorite game of many girls and women. Film Comment mentioned a woman who played Ms. Pac-Man exclusively, while a “Talk of the Town” piece in the New Yorker described an arcade on Fire Island, the resort near New York City, during the summer of 1982, where girls congregated to play the game. “Ms. Pac-Man players in the Arcade room are mostly gangs of four or five minigirls with one older babysitter—an elder person, usually female.”35 But elsewhere in the same village of Ocean Beach, at Mike the Greek’s and an ice cream parlor, Ms. Pac-Man was played by adolescent boys “who pound the glass and swear furiously—mostly unmentionables.” Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man alike appealed very broadly, and Ms. Pac-Man in particular has remained one of the most desirable arcade cabinet games for collectors and public locations for decades, still collecting quarters in bowling alleys, miniature golf courses, and pizza parlors years after its debut.

In the 1980s, the presence of girls and woman among these games’ faithful players not only guaranteed their commercial success, but also revealed the assumption that other video games were particularly of interest to young male players—that this was somehow natural rather than a social construct based on the growth of video games within a particular historical context. The novelty of female-favorite games reinforced the common sense that video games were a male preserve. At the moment when video games became omnipresent, mainstream popular media, the gendered reception of Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man showed the newly emerged medium to be safe and friendly and open to all. At the same time, this reception marking the feminine as different also showed that video games were still the way mainly young male players coming of age in the early 1980s worked out their gender identity by continuing in the boy-culture traditions of aggressive, competitive play, updated for the era of Star Wars and computers. Having a handful of games with a less intensely masculine character made room for other players without threatening the overwhelming young and male focus on video games more generally.

In the “Pac-Man Fever” episode of the short-lived teen comedy Square Pegs, which ran on NBC for one season in 1982–83, the suburban, middle-class, teenage boy Marshall becomes addicted to video games when they appear in the high school cafeteria—he gets addicted to Pac-Man—and he loses all interest in the things boys often care about, including girls.36 Marshall competes against another boy for a high score but neglects his social life and responsibilities because of his video game abuse. His friends recruit an attractive girl to seduce Marshall and break him of his obsession, but to no avail. Not even sexual desire can break the spell. Eventually, after he is comically cured in time for the closing credits, the episode ends on a tag with Marshall’s two friends Lauren and Patty encountering a new Ms. Pac-Man cabinet at the diner (“shouldn’t that be Ms. Pac-Person?!”). One asks the other for a quarter as she approaches the machine. This suggests a full-circle, “Here we go again” ending, but this time with a teenage girl having a turn at getting lost in this new form of seductive play. Of course, the focus of the whole episode on a boy getting hooked underscores the normative gendering of video games, while the humorous twist at the end gestures at inclusiveness. But surely Ms. Pac-Man was an opportunity for many girls in the 1980s to experience video games on their own terms rather than as a foray into boy culture. Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man allowed for this expansion of video games to make room for female players, but it did so without seriously challenging the deeper inequality within the new culture of electronic leisure.

Pac-Man Fever marks a culmination. By the time of Square Pegs, it’s fair to say, the medium of video games had closed off much of the flexibility of its meanings. What had been a newfangled gadget or novelty was by the fall of 1982 a fixture of everyday life, an unavoidable presence permeating pop culture. Pac-Man Fever could be caught by anyone. It was truly mass media, but this was in tension with a cloistered quality in the world of video games, a boy’s-club ideal that has endured decades after stores stopped selling Pac-Man socks and sweatshirts. Tensions between inclusiveness and exclusiveness, a core of subcultural fan identity and mainstream popularity, masculine fandom and broader appeals, have been an enduring legacy of early video games.

Like any emergent medium or technology, video games were not invented out of nothing, and they were never merely a neutral artifact to be used in whatever ways individuals desired. They came along within a set of long-standing social relations characterized by differences in power, authority, and opportunity. These differences structured social identities such as age, race, class, gender, and sexuality, and also dynamics in public places and in the home. Ideas about advanced technology, coin-operated amusements, and domestic recreation from long before the invention and emergence of electronic games shaped the development of the medium. Ideas about middle-class values, about forms of play for boys and girls, and about coming of age carried over from earlier times and earlier experiences of leisure. Contours of suburban and urban spaces, Cold War politics, transformations in labor and economics, the computerization of society, and fashions and styles in popular culture all left imprints on video games. Games were always understood through points of reference to already familiar objects and experiences, and to new ones emerging alongside high-tech play: spaceships real and imagined, TV sets and their possible uses, recreation rooms and the activities within them, arcades dusty or clean, computers old and new, and other toys with microchips inside. All of these objects and experiences came burdened with associations and expectations.

As the response to Pac-Man’s wild popularity shows, video games emerged into a defined cultural profile. Of course, not all players of video games in these years were young (teenage and young adult), male, and middle-class, but such players formed the core ideal of the medium in relation to its users. The material culture of early video games, the games as objects, their images, sounds, and gameplay, and representations of them in many media, contributed to this ideal, this widely shared sense of the medium’s value and its typical uses and pleasures. So did ideas imposed by guardians of morality and businesses standing to profit from games and their players. Both the games and the ways they were experienced contributed to a widely shared sense of their cultural status, a place in popular imagination. It was not inevitable that games should take on the identity that they did. A myriad of individual intentions, social forces, and background assumptions shaped this development. Later efforts to expand and renegotiate our expectations about video games and what they can and should be—and for whom—still struggle against the meanings worked out during this crucial formative period of emergence.