Adonijah’s Quest for the Throne (1:5–53)

“I will be king” (1:5). Because Adonijah was the next in line after Absalom’s death, his statement was in keeping with the customs of Israel and its neighbors. Legal documents dating to the second millennium B.C. from places such as Mari, Nuzi, and Assyria stipulate that the oldest surviving son always received the privileged position.26 Likewise, the Israelites were expected to give the firstborn son a double portion of property and to establish him as the head of the household. This practice, which was the norm for households and royal courts alike, served to preserve family resources and regulate generational transitions.27 Rank and status were assigned by societal norms rather than the father’s love for a particular wife or son.28 Many biblical characters did not adhere to this tradition, but examination of the passage’s ancient context clearly shows that Adonijah and some of the king’s advisors anticipated David would.29

Assyrian king in chariot is accompanied by entourage in front and in back.

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

So he got chariots and horses ready, with fifty men to run ahead of him (1:5). Chariots are well attested in archaeological excavation. When their remains are combined with textual and iconographic references, chariots can be reconstructed with a high degree of accuracy right down to the smallest fittings.30 They can be grouped according to the number of passengers and by the size and number of spokes in the wheels.31 Typical Israelite chariots were manned by an archer, a shield bearer, and a driver holding a spear.32 They were not only strategic weapons but also symbols of power and authority (Gen. 41:3; 2 Kings 10:16). The runners represent a royal guard independent of the regular army. They may also have been advisors to the king (see 1 Kings 18:46). Runners are depicted alongside chariots in the second millennium wall reliefs of temples at el-Amarna and Karnak in Egypt and are described in the annals of Assyrian kings (“those who run at the wheel of my lord”).33

They gave him their support (1:7). Two factions emerged in the court because of David’s failure to follow cultural norms and announce a successor when he became incapacitated. The failure of David’s special guard to join Adonijah’s followers was a clear indicator that David had yet to act. Adonijah’s entrance with chariot and a royal guard not only increased the tension between the king and traditional institutions, but also represented a premature appeal to power by force that violated religious and cultural protocols.34 David’s inaction therefore emboldened both parties and created a national crisis with rifts in the military, the priesthood, and the prophets.

Adonijah then sacrificed sheep, cattle and fattened calves at the Stone of Zoheleth near En Rogel (1:9). The religious pretext for the sacrifice is unclear, though it likely was intended to initiate a feast that would seal an alliance between those gathered.35 Near Eastern hospitality in antiquity, as today, implied loyalty and friendship. Adonijah achieved such relations with the Israelite aristocracy by inviting them to his gathering (see 1:25). Conversely, he did not invite his own brother Solomon or the opposing prophet, priest, and commander (Nathan, Zadok, and Benaiah) lest the age-old customs of hospitality prevent him from opposing them at a future time.

En Rogel, which is only about 250 yards south of the convergence of the Kidron and Hinnom Valleys. The view here is to the south from the southern tip of the City of David. The En Rogel spring is about in the middle of the picture just to the right of the red roofs.

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

En-Rogel was a spring located in the Kidron Valley, on the border between Judah and Benjamin, a short distance from Jerusalem (Josh. 15:7). This location was a broad, lush area with adequate space and resources for a large gathering. It also allowed for a slightly lower profile than the city itself, and its southern orientation expressed Adonijah’s affinity with his Judean base of support. The Zohelet stone was a landmark whose local significance is unknown, though the word’s meaning, “serpent,” may hint at religious activity in this location.36

Bathsheba went to see the aged king in his room (1:15). David’s palace in Jerusalem is thought to have been atop the mid-section of the City of David. Recent excavations have unearthed a large public building containing pottery from the period of David and Solomon.37 The structure is supported by a large support of stone and fill known in the Bible as the millo (2 Sam. 5:9; 1 Kings 9:15; 11:27). Bathsheba observed proper etiquette while approaching the king, though she seems to have had special access to him (cf. Judg. 15:1; Est. 4:11).

I and my son Solomon will be treated as criminals (1:21). Coup attempts were common in the ancient Near East. They inevitably led to bloodshed. A good example is the ascension of Esarhaddon, an Assyrian king in 680 B.C. Rival siblings killed his father and disputed his claim to the throne.38 Upon his victory he meted out collective punishment by killing the rebels, their aids, and their male descendants. In light of the ancient Near Eastern background, Bathsheba’s concern is an understatement.

Nathan the prophet is here (1:23). Israelite kings were anointed by prophets and ratified by the public before being coronated (2 Sam. 5:1–3; 1 Kings 12). David’s complete control of the outcome was unusual, and Nathan’s surprise at Adonijah’s actions was understandable. In surrounding cultures such as Mari of the second millennium B.C. and Assyria of the first millennium B.C., prophets of different titles served in the court. They frequently interpreted dreams and natural phenomena as harbingers of the king’s good fortune. Because court prophets in Israel derived their ultimate authority from Yahweh, they were less restrained from censuring the king. This helps to explain Nathan’s confrontational tone in verse 27 as well as his indictment in the earlier episode of David and Bathsheba (2 Sam. 11–12).

Set Solomon my son on my own mule and take him down to Gihon (1:33). David’s quick action rendered Adonijah’s feast an act of rebellion in practice and not just theory. He handed to Solomon several overt symbols of kingship, including his personal means of transportation as well as the go-ahead for anointing the public declaration at one of the royal city’s main landmarks.39 Mules were the preferred means of transportation among royalty, a fact corroborated by the second millennium B.C. letters from the kingdom of Mari (cf. 2 Sam. 13:29; 18:9). David’s personal mule was a visible proclamation of Solomon’s new status.

The excavated base of the massive gate towers by the Gihon Spring

Kim Walton

The reason for the procession’s march to the Gihon spring on the valley floor is unclear. It may have been a way to compete with Adonijah’s location. As the primary spring of David’s city, the Gihon would certainly eclipse En Rogel in importance and output. Recent archaeological exploration at the Gihon spring has exposed a massive water tower that was in use during David’s reign.40 It was a large and highly significant landmark, and the route from it to the palace would have been one of the main thoroughfares through the city, an ideal venue for Solomon’s emergence as king.

Have Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet anoint him king over Israel (1:34). Typically it was the prophet’s role to anoint a king. The unusual participation of the priest may have been a response to the support that Adonijah received from the rival priest, Abiathar. Priestly participation may also represent the completion of David’s work to establish Jerusalem (now also known as Zion with its preexisting Jebusite traditions) as the religious and political capital of Yahweh’s people (2 Sam. 7). Note how the priest personally brought the horn of oil specifically from the tent, Yahweh’s original residence in the holy city.41

Anointing scene from the Temple of Khonsu at Karnak

Manfred Näder, Gabana Studios, Germany

Kerethites and the Pelethites (1:38). These two groups are mentioned together so often in the Bible that it is reasonable to suggest a common ethnic and geographical origin. They belonged to David’s royal guard. By hiring foreigners for this service he ensured that his personal security was not dependent on Israelites who could become involved with persons or causes opposed to the king. Like many other attributes of David and Solomon’s kingdom, this practice is well attested in the Near East from the days of Abraham to the days of Jesus. The Code of Hammurabi and other Mesopotamian texts refer to reliable, well-paid mercenaries.42

The name Pelethites is commonly thought to derive from “Philistines,” but it may have some other origin. David first encountered the Kerethites in the Negev, a region of southern Israel, and worked for King Achish of Gath (1 Sam. 27). Most commentators trace the Kerethites to Crete (biblical Caphtor). There is no linguistic evidence to support this conclusion, but because Amos 9:7 traces the Philistines to Crete, the equation of Pelethites with Philistines indirectly supports a Cretan origin. Both mercenary groups appear to have Aegean origins and were known throughout the ancient Near East for their military prowess.43

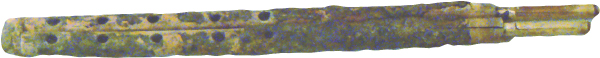

People went up after him, playing flutes and rejoicing greatly (1:40). Music and dancing accompanied most great events, sacred and secular. A ḥālîl or double reed pipe played at Solomon’s emotional procession (1:40). In the Bible this instrument is associated with the emotions of celebration (Isa. 30:29) and mourning (Jer. 48:36). The familiar šôpār that sounded at the announcement of Solomon’s anointing was not a trumpet but a polished, hollowed-out ram’s horn.44

Double flute

Kim Walton, courtesy of the Oriental Institute Museum

What’s the meaning of all the noise in the city? (1:41). Adonijah’s entire company at En Rogel heard the commotion and the trumpet from the Gihon spring because they were less than a mile away, around a turn in the Kidron Valley. The swiftness of events and the messengers was due to the close proximity of the two groups, despite their inability to see one another.

Adonijah … took hold of the horns of the altar (1:50). The purpose of the horns protruding from the altar is not known. Adonijah went to this location because, according to biblical tradition, it was a place of asylum for those who inadvertently committed murder (Ex. 21:13–14). Although he had not killed anyone, Adonijah expected to be executed for his actions and apparently thought the horns of the altar would be the best place from which to beg for his life and vow allegiance.45 This form of seeking asylum is so far unattested in the rest of the ancient Near East.

Horned altar

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

Large and small horned altars are known from sites throughout the Holy Land.46 A beautiful horned altar at Beersheba in southern Israel was found dismantled and built into a wall.47 The altar in the shrine at the adjacent Arad fortress was built according to the regulations of Exodus but also contained horned altars for incense in the holy space in the front of the shrine. The sacred precinct at Tel Dan also revealed a large altar, storage rooms, basins, and even small shovels for removing ashes and incense. Although they were built in contradiction to biblical law, these altars and their sacred contexts provide vivid comparisons to the official altar and its setting in Jerusalem.48 It has been suggested that antecedents of this altar design may be found in the Late Bronze Age Syrian terracotta tower models whose corners suggest a tower where rooftop rituals were performed.49

Solomon said, “If he shows himself to be a worthy man, not a hair of his head will fall to the ground; but if evil is found in him, he will die” (1:52). The expectation was that Adonijah would be killed for his insurrection. As David had done after Absalom’s revolt (2 Sam. 15–16), Solomon chooses to spare the usurper. The uncustomary nature of this action is reminiscent of an edict issued by King Telipinu of the Hittite empire in 1500 B.C. In response to decades of brutal fighting over the throne, Telipinu implemented a prohibition on the killing of political rivals and usurpers, regardless of social standing.50