Ahab’s Aramean Campaigns and the Prophetic Rebuke (20:1–43)

Ben-Hadad king of Aram mustered his entire army. Accompanied by thirty-two kings with their horses and chariots, he went up and besieged Samaria and attacked it (20:1). There were a number of Aramean kings named Ben-Hadad who ruled during the ninth century. There was a Ben-Hadad ruling from Damascus prior to, during, and after Ahab’s reign, and one of them was no doubt the king described in this chapter.360 This king’s ability to recruit so many other kings and chieftains was a rare achievement in the ancient Near East and is a testimony to Aram’s ascendancy in the mid-ninth century B.C.361 This leader of the Aramean coalition initiated a long series of trade wars with Israel. One can compare the coalition against Shalmaneser III in 853 B.C. and the attack on the city of Hamath in 800 B.C. as recorded in the Zakkur inscription.

Ruins of the Iron Age acropolis at Samaria

© Dr. James C. Martin

Ahab’s battles with Aram reflect an ongoing trade war between Aram and Israel that originated with the alliance between Israel and Phoenicia. This new arrangement, sealed by the marriage of Jezebel and Ahab, severely curtailed Aram’s access to the lucrative trade of Mediterranean ports. Ben-Hadad’s purpose was to isolate Israel and not necessarily to destroy its capital city of Samaria. If this chapter describes a traditional siege, the exquisite wall reliefs from Assyria can help the reader to visualize ancient siege warfare. Spears and flaming darts fill the air as captives submit and flames shoot from the windows and doors of city structures.362

A general campaign seems to be the more likely scenario in this showdown, however. Because of the geographical distribution of messages, scouts, and troop movement, the battle description apparently does not involve a protracted localized siege of Samaria (see comment on 20:12). Instead, this chapter must be read against the backdrop of the ongoing trade wars, the geography of the Israelite highlands, and the translation of the word bassukkôt in 20:12 (NIV: “in their tents”; cf. the alternative, “in Succoth,” presumably a staging area in Transjordan).363 These contextual data help to explain Ahab’s victory and the subsequent hesitation of Ben-Hadad to engage Israel in the hills (1 Kings 20:23).

Messengers (20:2). Diplomatic messengers were given safe passage regardless of the tension between their masters. In the eighth century B.C. Sefire treaty between Aramean kingdoms, all local kings were required to provide safe passage and open roads to messengers. Not to do so constituted a violation of the treaty.364 The Aramean messengers of Ben-Hadad played a pivotal role during the standoff with Samaria, and decisions of war and peace were dependent on their freedom of movement.

Your silver and gold are mine, and the best of your wives and children are mine (20:3). Because he was outnumbered, Ahab’s compliance to the first request was nothing less than a surrender. His words resembled that of a vassal responding to a lord in the deferential language of covenant treaties from the ancient Near Eastern world: “All I have are yours” (20:4). Were a battle to be fought, both sides of the conflict understood that the vanquished party would lose their primary possessions and most prominent persons.

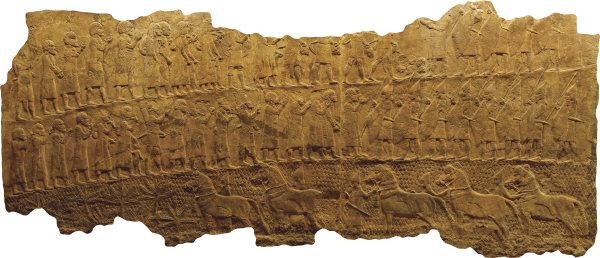

Exiles and animals carried away by Tiglath-pileser III

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

Such was the case in Esarhaddon’s and Ashurbanipal’s destruction of enemy kingdoms: “I carried off his wife, his children, the personnel of his palace, gold, silver … many valuables.”365 The Egyptian victors did the same. Amenhotep II boasts of seizing wives, children, animals, and “all of their property without end.”366 Reliefs from Tiglath-pileser III show captives and animals leaving Babylon and provide a chilling visual commentary to such texts.367

I am going to send my officials to search your palace and the houses of your officials (20:6). While the actions described in the preceding three verses resonate with coercive ancient Near Eastern surrenders, the thoroughness of the threatened search was a declaration of war. This escalation and the ability of Ahab’s advisors and commanders to crisscross the region help to explain Ahab’s abrupt change of tone.

The elders and the people all answered, “Don’t listen to him or agree to his demands” (20:8). This verse runs against common practice in the ancient world. Public outcry was seldom an option in the theocracies and monarchies of the ancient world. Most likely “the people” in this verse are the elders and clan leaders of the northern kingdom, who represent the views of the people. The semantic range of the Hebrew word “people” is broad enough to comprise military commanders and advisors, which may be the intent here (cf. 12:8).

One who puts on his armor should not boast like one who takes it off (1 Kings 20:11). The language of royal correspondence and diplomacy often invoked pithy sayings and proverbs. A good parallel to Ahab’s caustic reply is found in a letter from a local king to the Pharaoh of Egypt: “When ants are struck … they bite the hands that strike them.”368

He and the kings were drinking in their tents (20:12). The movements of messengers and troops in the verses that follow would not be possible were Samaria under a tight siege. For this reason and because both Zimri (16:9) and David (2 Sam. 11) previously had launched campaigns from the nearby region of Succoth, a city in the Jordan Valley, this verse may read, “He and the kings were drinking in Succoth.” Y. Yadin proposed this reading and it appears to be supported by the LXX. This interpretation also helps to explain the relatively free movement of Ahab’s army in verses 17–20.369

Meanwhile a prophet came to Ahab king of Israel and announced, “This is what the LORD says” (20:13). See comment on 22:5.

So Ahab summoned the young officers of the provincial commanders, 232 men. Then he assembled the rest of the Israelites, 7,000 in all (20:15). Relatively few details are known about the organization of the Israelite army, and the meaning of “provincial commanders” is unclear. The word [naʿar] can denote a soldier or “young officer” as in the texts of Ugarit and Late Bronze Age Egypt, but the cognate terms do not guarantee this translation.370 For an explanation of the number of persons assembled see comment on 20:29.

Ben-Hadad and the 32 kings allied with him were in their tents getting drunk (20:16). Among the depictions of military conquest in Egyptian temples and in Assyrian and Persian palaces are reliefs of banquet scenes and army camps set up on military campaigns. Some of the most impressive are the scenes from the throne room of Sennacherib of Assyria.371 On some of the reliefs the vanquished prisoners are paraded in front of the king, with grisly executions depicted in the background. For an alternate interpretation of “tents” in this verse, see comment on 20:12.

Assyrian review of prisoners

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

Strengthen your position and see what must be done, because next spring the king of Aram will attack you again (20:22). The Arameans would be unsatisfied with their geographical limitations until better access to the ports of the Mediterranean were secured. Israel alone stood in their way, and hence the Arameans would engage in battle again, next time in more favorable terrain closer to the Damascus heartland.

Their gods are gods of the hills (20:23). Chariotry and archers were better suited to the traditional battlegrounds of the open plain than to the narrow defiles of the central range. Moreover, Ben-Hadad had no desire to repeat the disaster recorded in the preceding verses.

Aphek (20:26). There are in Galilee several cities named Aphek. In this verse “Aphek” most likely refers to the Yarmuk Plain at the mouth of the Yarmuk canyon, an ideal staging ground for the armies of Aram and Israel that offered access to trade routes in all directions. Military campaigns typically occurred during the months of late spring and summer.372

Casemate wall and excavations at En Gev, the probable location of Aphek

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

Hundred thousand casualties … in one day (20:29). These are dramatic losses, but the Hebrew word ʾelep most likely refers to “units” rather than actual thousands. The number one thousand is likely derived from the size of a clan that would contribute the military unit.373

Wall collapsed (20:30). The massive walls of ancient Israelite cities required large foundations that could be undermined by sapper work as depicted in many Assyrian reliefs.374 Sections of the large walls at Megiddo, Mizpah, Lachish, and even the Millo of Jerusalem could easily kill two dozen “units” of defenders.375

Sappers undermining the foundations of the wall, Ashurnasirpal

The British Museum; © James C. Martin

Ben-Hadad fled to the city and hid in an inner room (20:30). The expression may or may not be a technical term for a specific room. It is unclear where the “room within a room” was located, but it was most likely a fortified space within the citadel of the city. A Hittite historiographic document describes an associate of the king going into the “inner chamber” and sitting before him on the right.376 The context implies a throne room or some portion of the king’s secure quarters.

Wearing sackcloth …and ropes around their heads (20:32). This clear sign of submission has parallels in both textual and artistic expressions in other ancient Near Eastern cultures. In a similar act of surrender King Shurpria of Urartu faced his Assyrian opponent and “took off his royal garment and wrapped his body in sackcloth befitting a (penitent) sinner.”377 One of the best-known pictures of sackcloth-wearing subjects is the detailed relief on the Ahiram sarcophagus from Phoenicia.378

Three pairs of warriors embracing to seal peace treaty on a basalt sacrificial basin

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, National Museum, Aleppo

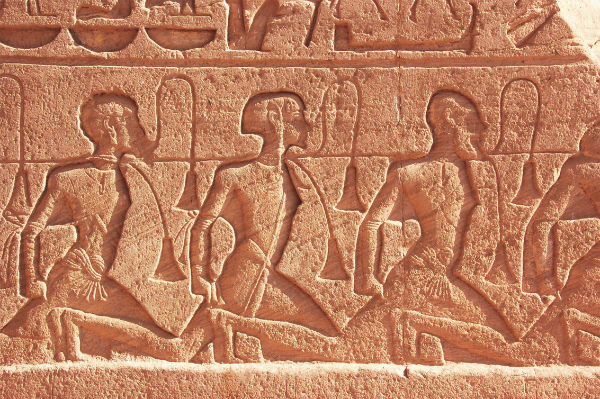

The ropes around the heads of the surrendering Arameans are most likely signs of their submission and willingness to be bound.379 Pharaoh Shishak’s Karnak relief shows local kings on their knees before the king, with ropes around their necks. By placing ropes on their heads the Arameans appear to have been acquiescing to Ahab in advance of being captured.

Prisoners of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel with ropes around necks

Frederick J. Mabie

He is my brother (20:32). This common diplomatic usage of the term “brother” indicates that Ahab still acknowledged the equal power and position of Ben-Hadad, whom he had just defeated. Compare the diplomatic parity reflected in the friendly dialogue between the kings of Tyre and Ugarit in the thirteenth century B.C.: “To the king of Ugarit, my brother, say….”380 The expression is often found in the preamble or conclusion of treaties between kings, as is the case here. By inviting Ben Hadad into his chariot rather than making him walk in submission by the wheel, Ahab was acknowledging publicly the agreement between the two kings. Rather than making Ben-Hadad into a vassal, he was extracting from him key territorial and economic concessions in return for his freedom.

Market areas in Damascus (20:34). The treaty is a further indicator that trade and economic gain were the motivation of this battle and the Aramean-Israelite wars generally. A good precedent of such tax-free trading centers is the Assyrian colonies in Anatolia that brought copper ore into Mesopotamia. These karums or land-based ports thrived in the second millennium B.C.381 Biran has suggested that such a marketplace is evidenced in the archaeological record just outside the gates of Dan.382

Marketplace outside the gate at Dan

Kim Walton

Talent of silver (20:39). A talent of silver was an impossibly large sum for an ordinary person (see comment on 9:14), and it virtually assured that it would be a life for a life if the man went missing. This was the price of two or more slaves in Mesopotamia and Egypt. Such a large sum of money, though exorbitant, is in keeping with the penalties recorded in other ancient Near Eastern cultures.383

Palace in Samaria (20:43). The foundations of the palace indicate that it was made in the two-storied, pillared courtyard bit-hilani style prevalent in the Levant during the early first millennium B.C.384 See comments on 16:24, 29.

Foundations of Ahab’s palace in Samaria

Bible Scene Multimedia/Maurice Thompson