Deliverance and Exile (20:1–21)

Middle court (20:4). As the context implies, this was the area between the temple and the palace. It was while Isaiah was still crossing this court that he received his new revelation.

Prepare a poultice of figs (20:7). Figs had long been cultivated in Palestine, and as well as being eaten fresh, they could be dried and made into cakes or fermented and made into wine. However, it is specifically their medicinal use that is in view here—a fig poultice is applied to what may have been an abscess. The belief that figs had medicinal qualities is also attested later in Rome182 and earlier at Ugarit, where we read in a veterinary text dealing with the care of horses:

If a horse [meaning of the two verbs unclear] incessantly, old fig-cakes and old raisins and flour of groats should be pulverized together, and it (the remedy) should be poured into his nose.183

Kudurru (boundary stone) of King Marduk-apla-iddina II (Merodach Baladan)

Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY, courtesy of the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin

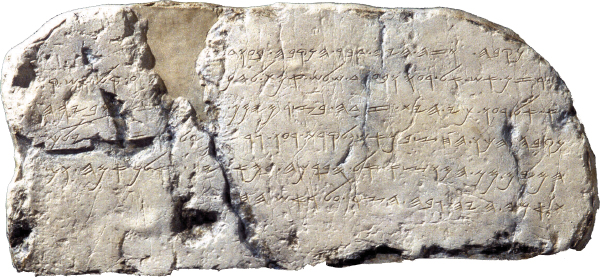

Sundial with Aramaean inscription, 6th century B.C.

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, the Archaeological Museum, Istanbul

Shall the shadow go forward ten steps, or shall it go back ten steps? (20:9). It has often been assumed that this refers to a device designed to tell time. Scholars refer in this context to ancient sundials in general (dating back to fifteenth-century Babylonia and Egypt) and in particular to the model of a house excavated in Egypt that contained two flights of stairs used for telling time.184 This is, however, to read a considerable amount into the biblical text.

Merodach-Baladan son of Baladan king of Babylon (20:12). When Sargon II ascended the Assyrian throne in 722 B.C., Merodach-Baladan (Marduk-apla-iddina II) had himself crowned king in Babylon,185 and there ensued a period of ongoing if intermittent conflict in Mesopotamia that lasted until Esarhaddon’s reign (see comments on 17:24 and 19:37). The visit of Merodach-Baladan’s envoys to Jerusalem is best set during the period in which he was still enjoying his first spell of kingship in Babylon (722–710 B.C.), before Sargon II reconquered Babylonia after 710 B.C. and drove Merodach-Baladan into exile.186

Second Kings 20:1–19 as a whole, in fact, represents a “flashback” to the period around 713/712 B.C., fifteen years before Hezekiah’s death (cf. 20:6). The visit suggests that the anti-Assyrian resistance that arose after Sargon’s death in different parts of the empire was coordinated rather than coincidental and had its roots in long-term prior contacts between the different groups involved in it. Hezekiah may have been involved at this time in a revolt against Assyria spearheaded by the Philistine city of Ashdod (see comment on 18:7).

Pool … tunnel (20:20). Settled existence in Syria-Palestine required adequate water supplies, or at least water supplies that could be made adequate by human interference with nature. Towns were often built, therefore, beside rivers and springs, so that the course of the rivers could be altered somewhat and the flow of springs could be improved. Wells were dug in order to access underground water; and rainwater from the wet months was collected in cisterns or reservoirs for later use. Particular attention had to be given to ensuring that towns possessed water sources that would enable them to withstand siege.

In the case of Jerusalem, the Gihon Spring in the Kidron Valley was the crucial resource, and a complex water system was created early in order to secure and access its water. An impressive tower was constructed in the Middle Bronze period (eighteenth to seventeenth centuries B.C.) to protect the spring, and a large, quarter-mile long conduit (often known as the Siloam Channel) channeled the water from there to the reservoir at Birket el-Hamra (perhaps the Lower [Old] Pool of Isa. 22:9–11) at the southern end of the City of David, gathering as it went run-off water from above and irrigating adjacent fields. Although well-protected by large boulders wedged in the channel, this water supply lay outside the city’s walls and was vulnerable in time of siege.

Hezekiah’s Tunnel

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

However, the Middle Bronze age water system also contained a subsidiary tunnel that led from the Siloam conduit, near to its beginning point by the Gihon Spring, into a large rock-cut pool, whence Jerusalem residents could draw water from above by way of a further tunnel that began inside the city walls. This water supply would have been especially useful in time of siege. Later, in preparation for the Assyrian attack, King Hezekiah had a tunnel cut that diverted water from the Gihon Spring directly underground to the Pool of Siloam (Birket es-Silwan) at the southern end of the Tyropoeon Valley—which now lay within the city walls (see the sidebar “The Walls and Gates of Jerusalem II” at 18:17). This not only secured his own water supply but also deprived the Assyrians of one (2 Chron. 32:4, 30). At this point the old water system was apparently abandoned.187