CHAPTER 22

A COST SYSTEM FOR A JOBBING PLANT

A COST-ACCOUNTING SYSTEM should provide cost figures that will enable management to make decisions such as the following for each type of goods manufactured:

How profitable is the product at present prices?

Can it be profitably produced to sell at a different price?

At what price shall it be sold?

Should its production level be expanded (or reduced)?

What can be done to control costs that are out of line?

If only a few kinds of products are made and the manufacturing processes are always the same, these decisions can be made on the basis of average per-unit cost figures computed each month. Either of two methods can be used to compute the average costs: (1) Divide the total manufacturing cost by the number of product units produced. (2) Compute the unit costs of the individual processes and total them. In both cases, in figuring the number of units produced, changes in the inventory in process must be taken into consideration.

Suppose, on the other hand, that many different types of products are made and that selling-price agreements are based on recorded costs. This is likely to be the case where a jobbing plant produces goods for many different customers to the individual customer’s specifications, or for a single customer whose specifications change often.

In such cases, the cost-accounting system must be set up so that product costs can be determined more directly. These systems are referred to as job cost systems or production-order cost systems. If each product unit requires a large dollar outlay, costs are assigned directly to each unit. For less costly units, costs may be assigned to groups or batches of like items and unit costs computed as an average for each group.

Journals and Ledgers

The cost accounting system for any manufacturing enterprise should include an integrated group of journals, ledgers, basic cost records, and control records. The number and kinds of journals and ledgers will depend on (1) the type and volume of transactions with outsiders and (2) the type and volume of cost transfers made necessary by the manufacturing techniques.

For a very small shop, a combined journal from which all postings to general and factory ledger accounts can be made is satisfactory. If the volume of entries is large enough to require several persons for the bookkeeping, separate books of original entry such as the following will be needed:

- Voucher register

- Check register

- Cash receipts journal

- Sales journal

- Factory journal

- Payroll journal

If all activities—manufacturing, administrative, and selling—are carried on in a single location, a general ledger with some subsidiary records is adequate. Subsidiary records will be needed for production jobs and certain other items such as accounts receivable, raw materials, and accounts payable.

If the general office is not at the same location as the factory, it is usually best to use a factory ledger in addition to the general ledger. Reciprocal accounts in each of the ledgers show the net balances of the accounts in the other ledger and so provide for self-balancing. In this way, many of the details of accounting for manufacturing costs can be confined to the factory ledger.

Control and Cost Procedures for a Job-Order Plant

The distinctive features of a job-order cost system are primarily in the basic cost and control records. The following is a typical set of these records:

Orders and reports containing physical-product information:

Production order

Production control record

Daily production report

Route card, or job-order instruction card

Orders and reports containing both physical-product and dollar-cost information:

Material requisition

Job timecard

Job-cost record

Production-cost summary

Control Records

The orders and reports containing physical-product information only—such as production orders or daily production reports—are control records. They are used primarily in the plant work areas for scheduling and planning production.

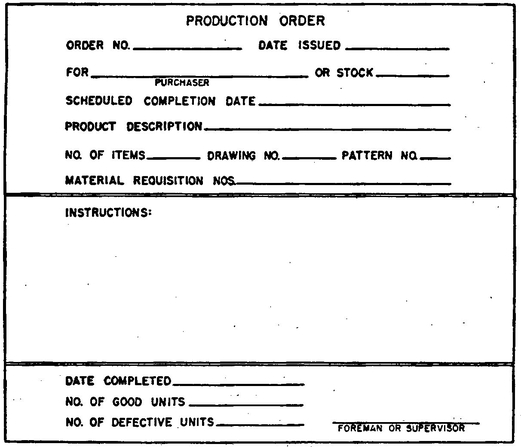

PRODUCTION ORDERS. Exhibit 1 shows a typical production order form. This form is used by the production manager to initiate production activity. When a job is ready for production, or when the inventory of finished products needs building up, the production manager authorizes the start of work by issuing a production order. He keeps one copy and sends a copy with the necessary instructions to each department or machine operator to be involved in the production.

This procedure provides a means for establishing production priorities and makes it possible for all departments or operators to plan for jobs that are coming up. Each department or operator keeps a file of pending orders arranged by the expected sequence of work. The foreman or the production manager can then check from time to time and readjust the job sequence as needed. The aim, of course, is to make sure that successive operations on all orders are scheduled as efficiently as possible.

When manufacturing operations are highly mechanized and the volume of production near capacity, machine loading is of prime importance. In such cases, an employee or group of employees may be assigned to analyze production orders and schedule the machines so as to get the maximum use from the plant’s facilities.

Exhibit 1.—Production order

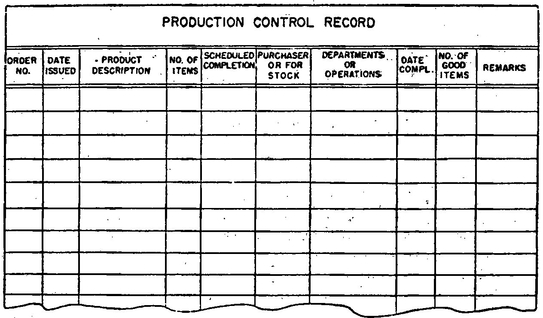

PRODUCTION CONTROL RECORD. The person responsible for control of production needs some sort of record or file to show the status of all jobs in process. A typical production control record is shown as exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2.—Production control record

When the production manager issues a production order, he enters the order number and other details on the production control record. In the column headed “Departments or operations,” the numbers or other identifying codes of all departments that will work on the job are entered. As the order moves through the factory, one department after another is checked off, showing where the job stands at any time.

The production control record is thus an up-to-date running history of all production activity. It shows where the factory stands in terms of jobs, units of product, and stages of completion. It is a means of control over all work in process. Furthermore, it is a ready source of information when customers ask about their orders. The information should also be used, along with sales orders or forecasts and stock records of finished products, to determine the need for new production orders.

The form shown as exhibit 2 is just an example. How elaborate a form is needed depends on a number of factors—the number of operations, the number of jobs usually in process at one time, the length of time required to finish each job, the amount of detailed information needed by management. If production operations are numerous or jobs differ greatly, it may be better to use separate control cards (filed numerically) for each job. The production order form (exhibit 1) can be used for this.

Other methods can be used to control production—blackboard and chalk, pegboard layouts, mechanical visual aids, electronic equipment. The best method for a small manufacturing firm is the one it finds easy to understand and whose cost in money and time it can afford.

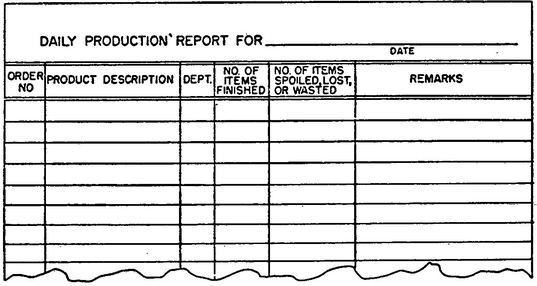

Exhibit 3.—Daily production report

DAILY PRODUCTION REPORT. The daily production report (exhibit 3) provides the data for recording job progress on the production control record. Each morning the production manager should see that the preceding day’s production is checked for each department or operation and recorded on the daily production report.

If each job calls for only one product unit, or very few units, the entries should show only the jobs completed by each department. If each job is made up of a large number of product units and requires at least several days to complete, a more detailed record is needed. For such jobs, it is important to show the number of individual units completed by each department so that the stage of completion of each job in each department may be known.

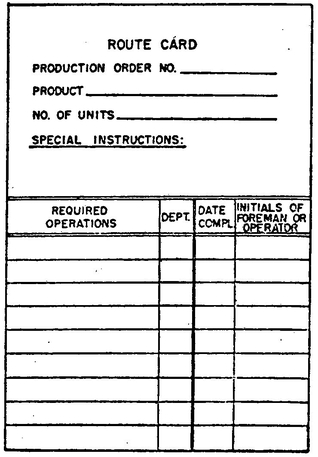

Exhibit 4.—Route card or job order instruction card

Showing on the daily report the number of units lost, wasted, or spoiled uncovers trouble spots promptly. If necessary, future operations on the jobs in process can be rescheduled.

ROUTE CARD OR JOB-ORDER INSTRUCTION CARD. Route cards help direct the movement of jobs through the plant. They also serve as a running history that can be used to trace responsibility for either substandard workmanship or exceptional efficiency.

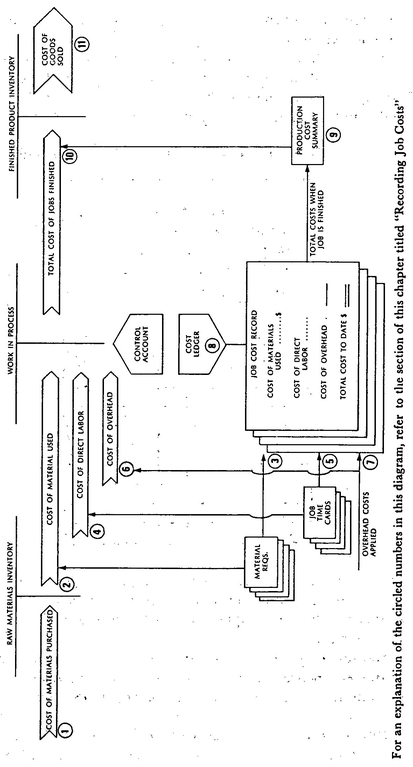

Exhibit 5.—Cost records and accounts for a job-order plant

A route card, or job-order instruction card (exhibit 4), should be prepared before each production order is issued. This card goes to the department or employee who will work on the order first and then accompanies the job through all operations. Each employee or foreman handling the job enters on the card the date the employee’s operation is completed and his or her initials.

Recording Job Costs

The techniques discussed so far are control techniques. The forms shown in exhibits 1 through 4 are in terms of units rather than dollars and cents. They tell what, how much, and where, but not how much money is involved in the units and activity. Other records are needed to gather product cost information.

For a jobbing plant, the four basic cost records, already listed on pg. 154, are the materials requisition, the job time card, the job cost record, and the production cost summary. These basic cost records should tie in with the overall accounting system. Their relation to accounts in the general or factory ledger is shown in exhibit 5. (The section numbers in the explanation that follows refer to the corresponding circled numbers in exhibit 5.)

1. The cost of materials purchased is recorded in the Raw Materials Inventory account from vendors’ invoices. The entry will read as follows:

| Debit | Credit | |

|---|---|---|

| Raw materials inventory | xxx | |

| Accounts payable | xxx | |

| To record the purchase of raw materials. | ||

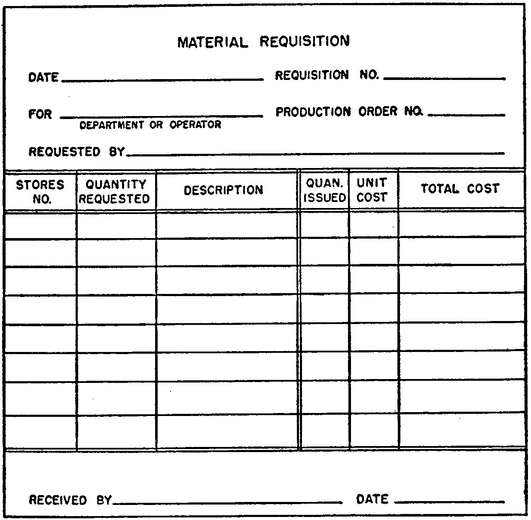

2. The Materials Requisition (exhibit 6) is used to authorize all withdrawals from a storeroom or stock of raw materials. The requisitions should be prepared by someone who knows exactly what materials are needed for the job—for example, the planning department, production engineer, or production manager. Only authorized individuals should sign requisitions.

Exhibit 6.—Material requisition

If more materials must be issued to a job already started, it may mean too much waste or spoilage. A colored requisition for added-on issues will call attention to this possibility.

The materials costs entered on the requisition are based on the unit costs shown in the Raw Materials Inventory account. They are the basic record from which a journal entry is made to transfer costs from the Raw Materials Inventory to the Work-in-Process account, as follows:

| Debit | Credit | ||

| Work in process | xxx | ||

| Raw materials inventory | xxx | ||

| To transfer materials cost to work-in-process account. | |||

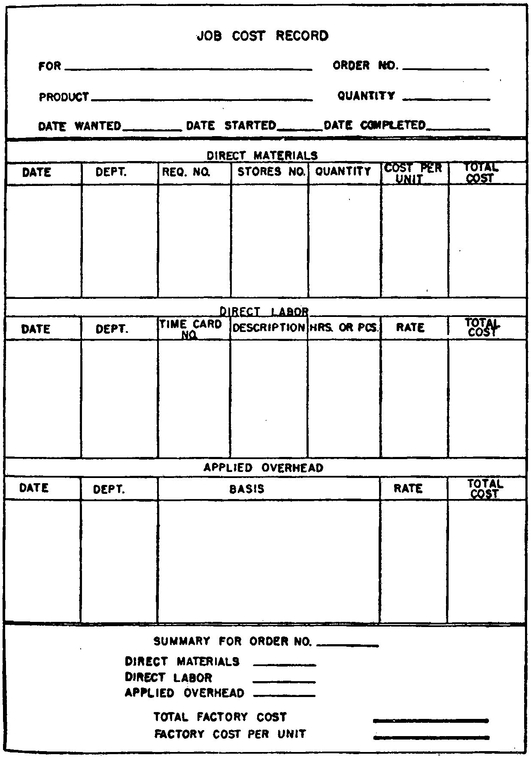

3. The materials requisition is also the basic cost record for recording materials costs on the Job Cost Record (exhibits 7 and 8). Direct labor and overhead costs will be added to give the total manufacturing costs of each job.

Exhibit 7.—Job-cost record for a departmentalized plant

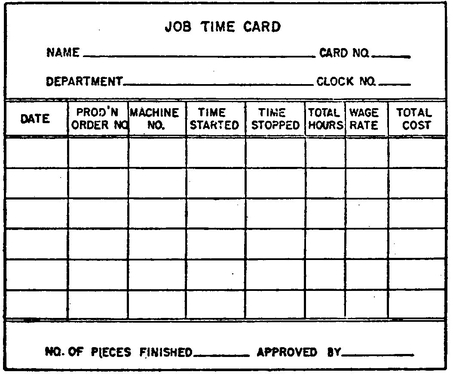

4. Before each production order is run, the planning department or the department foreman prepares a Job Timecard (exhibit 9) for each worker who will do any part of the job. Every time the operator starts or stops work on the job, the employee has his or her card time-stamped. When the employee finishes the job, the card is time-stamped again and completed.

The Job Timecards provide information for preparing the operator’s paycheck.

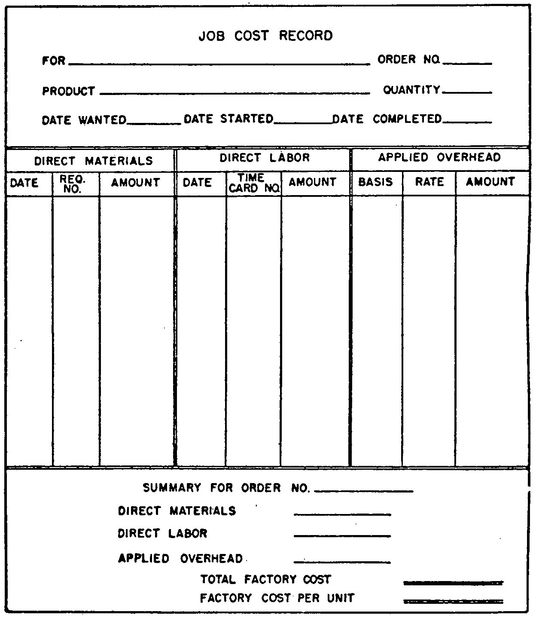

Exhibit 8.—Job-cost record for a nondepartmentalized plant

5. A cost clerk collects the Job Timecards daily or weekly. The clerk figures the labor costs and sorts the cards by production orders. Then the clerk records the direct-labor costs on the Job Cost Record for each job on which work has been done. Some production orders may require days or even weeks in one department. When that is the case, daily job timecards may be needed to keep the Job Cost Records current.

Exhibit 9.—Job timecard

6. The Cost of Overhead includes all manufacturing costs except direct materials and direct labor. These costs cannot be assigned to or identified with individual jobs, so they are applied to jobs on the basis of so much per direct labor hour or machine hour, or on some other basis.

7. Once the method for distributing overhead cost has been decided, the overhead cost can be calculated for each job and entered on the Job Cost Record. The Job Cost Records should show the overhead rate and basis used as well as the amount applied to the job.

8. On any date, the Job Cost Record (exhibits 7 and 8) for a given job shows all the costs of the job—direct materials, direct labor, and overhead applied—as of that date. All the job cost records together make up a subsidiary, or special, ledger called the cost ledger.

These costs are entered also in the Work-in-Process account in the general ledger. The accounting entries here are usually monthly totals from the materials requisitions, job time cards, and overhead application calculations. The Work-in-Process account is called a control account because its balance is always equal to the total of all costs of uncompleted jobs in the cost ledger.

In some cases, it may be more convenient to use three work-in-process accounts—Material—in—Process, Labor-in-Process, and Overhead-in-Process-than to put all costs into a single account. But no matter how many work-in-process accounts are used, the principle is the same: When all accounting entries have been made, the total of the costs shown on the uncompleted job-cost records should equal the total costs in the work-in-process account(s).

The job-cost records are the hub of any cost system for a jobbing plant. The entries made on these forms are the end result of all the procedures used to gather cost details.

Just what type of job-cost records will be used depends on a number of factors—the number of types of raw materials and component parts used; the length of time required to complete each job; the number of employees doing direct labor on each job; the basis for applying overhead; the number of different overhead rates (for different operations); the degree to which the factory is departmentalized; and any special production or accounting techniques used.

The fundamental requirements, however, are always the same. There must be space for job identification; for periodic entries of direct material, direct labor, and overhead costs; and for a summary of total costs. Exhibits 7 and 8 (pages 162–163) show typical job-cost record forms for departmentalized and nondepartmentalized plants.

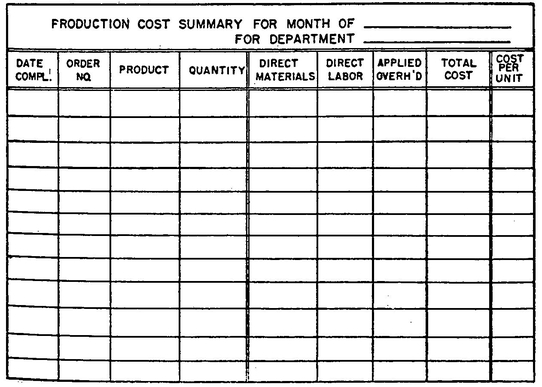

9. When a job is finished, entries are made on the Production Control Record (exhibit 2, ) and on a monthly Production Cost Summary similar to the one shown as exhibit 10. The data for the Production Cost Summary are taken from the summary section of the Job Cost Record. This report is a useful source of end-result cost information for the management of a manufacturing business.

10. At the end of each month or whatever period fits the cycle of manufacturing activity, the total costs of all completed jobs, as shown on the monthly Production Cost Summary, are entered in the journal. This journal entry transfers costs from the. Work-in-Process account to the Finished-Product Inventory account:

| Debit | Credit | |

| Finished product inventory | xxx | |

| Work in process | xxx | |

| To transfer costs of completed jobs to finished product inventory. | ||

11. When finished products are sold to a customer, either on special order or out of inventory, the costs of those products are taken out of the inventory account and charged to the Cost of Goods Sold account. (The Cost of Goods Sold will appear in the income statement.)

Exhibit 10.—Production cost summary

| Debit | Credit | |

| Cost of goods sold | xxx | |

| Finished product inventory | xxx | |

| To record the sale of products. | ||

This chapter has outlined the basic steps in a cost-accounting system for a jobbing plant. No matter how complex the manufacturing operation, a cost system must embody these same techniques, expanded or adapted to meet the specific needs of the management.