For years, the Fellowship Commission has been anxious to get into TV regularly, feeling that it is probably the most effective medium for forming desirable attitudes.

—Maurice Fagan, Executive Director of the Philadelphia Fellowship Commission and host of They Shall Be Heard, 1952

They Shall Be Heard is a road not taken. While Bandstand introduced Philadelphia teenagers to new popular music, dances, and fashion styles, another local program used television to educate teenagers about intercultural issues. Produced by the Fellowship Commission, They Shall Be Heard (1952–53) gathered a group of teenagers for a weekly televised discussion about racial and religious prejudice. Unlike Bandstand, which adopted admissions policies that excluded black teenagers, They Shall Be Heard brought together students of different racial, religious, and ethnic backgrounds. As Bandstand marked television as a place restricted to white teenage consumers, They Shall Be Heard introduced its audience to ideas and discussions beyond the limited boundaries of Bandstand’s commercial entertainment.

While Bandstand’s producers defined local television by the scope of WFIL’s consumer market, the Fellowship Commission’s vision for local television focused on the Philadelphia city limits. As Philadelphia’s leading interracial and interreligious civil rights coalition, the Fellowship Commission worked through the late 1940s and 1950s to secure antidiscrimination laws and improve race relations in the city.1 The Commission also worked closely with the school board to implement intercultural education materials designed to introduce students to the histories of different racial and religious groups and to counter stereotypes. Maurice Fagan, the executive director of both the Fellowship Commission and the Jewish Community Relations Council, led the group’s education program (Fagan’s work on educational issues is discussed in greater detail in chapters 3 and 4). By the early 1950s, the Fellowship Commission enjoyed a close relationship with the school board, but it still lacked a connection to most neighborhoods and schools. Fagan articulated his concerns about these shortcomings in a speech to the Commission’s members. “We are still far too middle class in our contacts and program,” Fagan advised the group. “We too rarely reach either the upper or lower economic groups and neighborhoods. We are too dependent upon public relations techniques to reach the rank and file members of the groups we contact. We need to find ways to personalize and decentralize our activities.” Fagan went on to suggest a way the group could address this issue. “Radio and television stations offer us more time than we are prepared to use well,” he noted, “but we haven’t even begun to work out ways of using television for educational purposes.”2 With these community relations goals in mind, Fagan and the Fellowship Commission approached They Shall Be Heard with optimism about television’s potential to reach viewers, especially in the racially changing neighborhoods in which they lacked contacts.

The Fellowship Commission was one of a number of public and private agencies (e.g., DuPont, the Ford Foundation, the Fund for the Republic, and the AFL-CIO) that sponsored civic-oriented programs across the country in television’s early years. These groups, media studies scholar Anna McCarthy has shown, looked to television as a tool to shape viewers’ “conduct and attitudes” toward “rational civic practice.”3 The businessmen, labor leaders, social reformers, and public intellectuals who organized these efforts held differing ideas about good citizenship, but all saw television as a strategy of governance. The shows, McCarthy notes, did not always work as intended, and the groups “often discovered a profound discrepancy between the effects they hoped to achieve and the responses of their viewers.”4 The programs, moreover, frequently addressed viewers as problems to be fixed. As media studies scholar Ien Ang has argued in the context of British broadcasting, producers of public service programs, like commercial programs, frequently view their audience from “above” or “outside” as “objectified categories of others to be controlled.” Whether addressing consumers or citizens, Ang suggests, television producers cannot stop “struggling to conquer the audience.”5 Like these efforts to shape citizenship, the Fellowship Commission looked to television for ways to engage and influence Philadelphians. The program it created, however, consciously tried to avoid the paternalistic tone common to public service programs. To address viewers as citizens without condescending to them, They Shall Be Heard deemphasized expert opinions in favor of unscripted discussions among “ordinary” teenagers. Fagan, in his role as moderator, sat off camera, encouraging viewers to focus on the young discussion participants. They Shall Be Heard’s producers sought to mitigate the power differential inherent in civic-oriented programming by respecting their audience’s ability to be active participants in a televised discussion rather than passive viewers of a televised lecture.

Contrasting They Shall Be Heard and Bandstand illuminates the advantages enjoyed by the commercial model for teenage television. Unlike They Shall Be Heard, which relied on a voluntary goodwill agreement between a network affiliate and the school system, Bandstand could count on advertisers eager to reach potential consumers in “WFIL–adelphia.” This inequity was owing to television’s development along the advertising-supported model of radio. As noted in chapter 1, in the postwar years the FCC allocated television licenses along the narrow VHF band, with most of the licenses going to established media companies that already owned newspapers and/or radio stations. The two major networks, NBC and CBS, dominated these VHF stations, with ABC gaining affiliates over the course of the 1950s. This left little space for educational television or other noncommercial stations, and when they did develop, most were assigned to the UHF band, which viewers could not receive without special equipment. Commercial stations made only token attempts to serve the public interest, and the FCC did little to hold these stations accountable. Government decisions, therefore, facilitated the dominance of commercial television and made the survival of civic-minded discussion programs like They Shall Be Heard tenuous.

Bandstand and They Shall Be Heard both debuted in October 1952, but their different understandings of local television led them to address their audiences in different ways and sent the shows on divergent trajectories. Bandstand addressed its audience as consumers and asked them to buy products, while They Shall Be Heard addressed its audience as citizens and asked them to reject prejudice. Bandstand succeeded and expanded because it was profitable; WFIL produced it inexpensively, and advertisers supported the show because it allowed them to reach the valuable teenage consumer demographic. They Shall Be Heard became a brief television experiment because it relied on the cooperation of television stations for airtime and because the Fellowship Commission was unable to establish a link between They Shall Be Heard’s “hearts and minds” approach to prejudice and the concurrent efforts undertaken by the Commission and other civil rights advocates to uproot structures of racial discrimination. The Fellowship Commission’s antidiscrimination message was simply a harder sell than Bandstand’s pop music and bubblegum. Although They Shall Be Heard ran for only twenty-seven episodes and reached only a fraction of the number of viewers that Bandstand did, it offers an alternative model in which television’s power to educate and challenge citizens took priority over television’s power to persuade consumers.

In their desire to explore the opportunities offered by television, Maurice Fagan and the Fellowship Commission built on earlier successes with radio broadcasts and film discussions. As did Americans All, Immigrants All, a national radio program about immigrant contributions produced by the Bureau for Intercultural Education in the 1940s, the Fellowship Commission’s Within Our Gates brought Philadelphians radio profiles of famous men and women of different racial, religious, and national backgrounds every Sunday morning from 1943 to 1952 on WFIL–radio.6 The school board recommended Within Our Gates for out-of-school study, and copies of recordings and scripts were made available to the city’s schools.7 In addition, the Fellowship Commission maintained a library of short filmstrips and feature-length films on topics related to intercultural relations. The Commission made these films available to teachers in the school system, and from 1948 to 1952 it offered bus service that transported school groups to the Fellowship building, where a Commission member led a discussion of the films.8 During 1951 alone, the Commission counted fifty-eight school classes and more than fifteen hundred students that used the free bus service to visit the library. Approximately twenty thousand people saw one of the Commission’s films or filmstrips in schools or community meetings.9

In both title and content, They Shall Be Heard drew inspiration from They Learn What They Live (1952), a study of prejudice in children co-sponsored by the Fellowship Commission.10 Conducted from 1945 to 1948 in Philadelphia’s public schools, the study received national attention for its findings about the early age at which young people develop racial awareness and prejudice.11 The study was part of a larger movement that encouraged schools to incorporate intercultural educational materials and perspectives into the classroom.12 Fagan and the Fellowship Commission were familiar with much of this work, but they were less concerned with the academic debates over intercultural education than they were with developing strategies for accessing and reducing prejudice in Philadelphia’s schools. The Fellowship Commission’s longheld interest in new approaches to intercultural education led it to They Shall Be Heard.

Drawing on these experiences, in October 1952 the Fellowship Commission brought its intercultural education ideas to a larger audience with a televised discussion with junior and senior high school students. In contrast to Bandstand’s solid financial backing by WFIL and Walter Annenberg’s Triangle Publications, They Shall Be Heard aired on Philadelphia’s NBC affiliate (WCAU-TV) through a system of voluntary cooperation between the station and the city’s public, private, and parochial school systems. Under this goodwill agreement, commercial stations would donate time for community and educational programming. This cooperation worked better in Philadelphia than in any other city, with all of the city’s television stations providing time to the schools in the early 1950s. In her 1953 study of educational and community television across the county, for example, Jennie Callahan noted that Philadelphia was home to the “the largest community activity in educational television in the country.”13 The viability of They Shall Be Heard and other community and educational programs, however, depended on the willingness of commercial stations to continue providing airtime. Indeed, the cooperation that brought They Shall Be Heard to television was short-lived, and the show did not return in the fall of 1953. Although the program ran for only twenty-seven episodes, They Shall Be Heard represented the Fellowship Commission’s most ambitious and innovative intercultural educational endeavor.

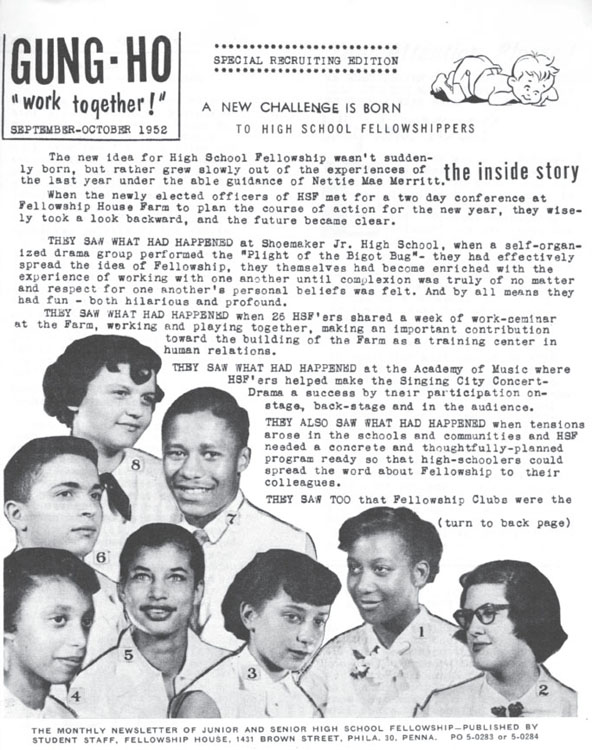

For this television program, the Fellowship Commission brought together students of different racial, religious, and ethnic backgrounds. To recruit students for the show, the Commission relied on the strength of its relationships with the public, private, and parochial school systems. Each of the three school systems recommended four students for each weekly program, drawing primarily from students in the schools’ Fellowship Clubs. The group of twelve students changed every week, so that over the course of the show’s run, more than three hundred students participated.14

The Fellowship House, an organization distinct from the Fellowship Commission run by Marjorie Penny, cofounder of the Commission, coordinated the high school Fellowship Clubs. The Fellowship House relied on teachers at the high schools to sponsor Fellowship Clubs as extracurricular activities. At the time They Shall Be Heard debuted, eight of the twenty-one public high schools had active Fellowship Clubs. In addition to appearing on the show, young people in the Fellowship Clubs challenged the discriminatory practices of recreational facilities, such as roller-skating rinks.15

FIGURE 9. High School Fellowship Clubs brought together students of different racial, religious, and ethnic backgrounds. The students pictured in this club newsletter are among those who would have participated in They Shall Be Heard. September-October 1952. Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, PA.

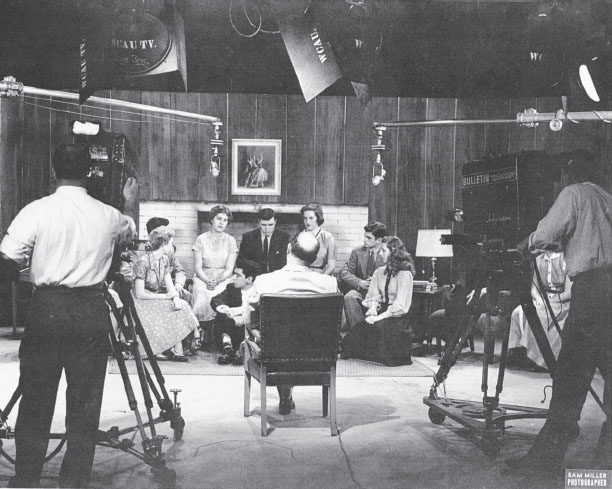

Although the producers did not make a kinescope of They Shall Be Heard, letters, memos, and photographs reveal a great deal about the structure of the program. Fagan, who was a former high school social studies teacher, served as the moderator of the discussion and played an important role in choosing the show’s subjects. The topics for the programs ranged from issues related to students’ schools, peer groups, and families to discussions of prejudice against racial, religious, or ethnic groups. Among this diversity of topics, episodes of the show considered “problems of students with foreign-born parents,” “fair educational opportunities,” “the atomic bomb,” “color prejudice,” “social rejection,” and “rejection of students with high or low I.Q.”16 As the moderator, Fagan attempted to stimulate discussion by relating these topics to the lives of the teenage students. For example, in a show that asked “How far can personal liberty be extended?” the discussion focused on “hotrodding.” The teenagers debated whether special roads should be provided for car racing, whether their personal liberties conflicted with the potential emotional and economic costs to their parents should they be injured, and whether hot-rodding could be considered a religiously prohibited form of suicide.17 As this example suggests, the show’s discussions of prejudice and interracial issues sometimes took a backseat to topics that Fagan believed would capture and maintain the interest of the show’s teenage panelists and television audience.18

Along with these unscripted discussions, Fagan also emphasized that the discussions be accessible to participants without any specific background knowledge in the subject. Here, Fagan contrasted They Shall Be Heard to Quiz Kids, a popular radio program in the 1940s and 1950s. Fagan informed a magazine editor that They Shall Be Heard “is not a ‘Quiz Kid’ program designed to present how much these youngsters know about a particular subject or even how bright they are. It is intended primarily to indicate how a group of fairly typical youngsters think about current human relations issues.”19 One student who participated in the program appreciated this approach and wrote to Fagan to encourage him to “continue this pattern of choosing subjects that will reveal the emotions and thoughts of students rather than their aptitudes and specific abilities.”20

While Fagan exercised control over the show’s subjects and provided the participants with discussion tips during the pre-show warm-up, he minimized his role as moderator during the broadcast itself. The Fellowship Commission’s experience with film discussions influenced this decision to downplay the moderator’s speaking role and emphasize the discussion among teenagers. For Fagan, discussion was an effective educational technique for two reasons. First, he thought it made students more amendable to intercultural attitudes. “Film-discussions,” he argued in a 1947 issue of Education magazine, “are vastly superior to speeches or straight teaching because the children find the facts for themselves and probably will accept them more readily and retain them more permanently.” Second, Fagan felt that discussion allowed educators to “spot pupils who are thoroughly democratic and others who are bigoted,” and to address “preventative” or “curative” intercultural work accordingly.21 The role of the moderator of They Shall Be Heard, therefore, was to facilitate exchanges that would reveal the opinions and attitudes of the participants without dominating the discussion. Fagan reiterated both of these points in a letter to a viewer who expressed concern with his muted role as moderator. “You must remember,” he told the viewer,

that these discussions are unrehearsed and, therefore, that youngsters will say things with which many or all of us may disagree but that the whole purpose of the programs is to bring such viewpoints out in the open where their faults could be shown and better ones could be developed. Since an important part of the program is to promote a free exchange of opinions … it is therefore important that these young people should not feel we are dominating their thinking or asking them in advance to agree with our thinking.22

In another letter, Fagan emphasized that “We take every pain to make sure that the moderator does not lecture, does not dominate the discussion with his own facts or views and does not manipulate the discussion.”23 They Shall Be Heard also used film clips and skits to stimulate discussion of racial prejudice. In each program, after Fagan explained the topic of discussion, he introduced either a film segment or a dramatic skit in which the students participated. For the former, the producers relied on the Fellowship Commission’s library of films with intercultural themes. Using films on the undemocratic nature of racial discrimination, such as Brotherhood of Man and Home of the Brave, the producers selected scenes that presented the episode’s subject provocatively.24 In episodes that featured skits, the producers selected four or five students during the warm-up period. Students did not memorize lines, and Max Franzen, the Fellowship Commission’s director of radio and television, admitted that “the skits were anything but professional jobs.”25 Nevertheless, these skits were central to exploring the themes of each show. For example, in an episode on fair educational opportunities, four students discussed their ambitions for college education. The dramatic tension in the brief skit flowed from the disappointment of one student who could not afford to go to college and of another who was turned down because of his race.26 In this and other episodes, after introducing the film or skit, Fagan attempted to stay out of the discussion and encouraged the students to ask questions of each other.

This discussion format, Anna McCarthy notes, was popular among local civic groups that sponsored public service programs. “The act of watching the act of having a discussion,” McCarthy suggests, “was a form of directive training, showing audience members appropriate and inappropriate forms of civic conduct.”27 Similarly, Fagan hoped that the discussions on They Shall Be Heard would influence the attitudes of teenage participants and television viewers and spark similar conversations among teenagers outside of the studio. By letting “average” teens talk through their ideas and concerns, moreover, the show challenged the custom of featuring well-known personalities or experts, which was emerging as the standard practice of television interview and discussion programs in this era. On nationally televised news programs like Edward R. Morrow’s See It Now (1951–58) and variety talk shows such as Arthur Godfrey Time (1952–59) and The Today Show (1951–present), the hosts acted as central figures who interviewed major newsmakers and entertainers.28 On NBC’s Youth Wants to Know (1951–63), a national public affairs program broadcast from Washington, D.C., that most closely resembles They Shall Be Heard, local high school students asked questions of prominent guests (John Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Eleanor Roosevelt, Jackie Robinson, James Michener, Estes Kefauver, and Joseph McCarthy all appeared on the show during its first five years).29 Unlike Youth Wants to Know, which made the famous guests the focal points of each episode, the producers of They Shall Be Heard distinguished their program from a typical news interview show by not providing detailed information on the students’ backgrounds or qualifications for appearing on the show. This lack of information prompted a letter from the editor of Exhibitor magazine, who complained that the program would have been “far more interesting had each of the participants been identified as to name, [grade], and school. In that way, those listening could have known the background of the students and could have tied it in with the viewpoints which they presented.”30 Fagan replied that the WCAU-TV producers, whom he felt were more “qualified to judge what makes for good television,” made the decision to omit this information, but that he felt that background information would “negate our purpose, which is to free the school from any embarrassment or endorsement of the views expressed and to give the youngsters the feeling that they can give their frank opinions as individuals.”31 This anonymity was in stark contrast to Bandstand’s roll call segment, in which teens introduced themselves by name and school. They Shall Be Heard’s decision to omit this information, when combined with the rotating cast of participants, helped to encourage the audience to see the students as “typical youngsters.” The Exhibitor editor, however, remained unconvinced by Fagan’s views:

I still feel that there could have been more background information as to the youngsters, yourself, and the purpose of the program before it started. While it may be that you wish to avoid the usual and stereotyped that one sees in similar evidence on television these days, I do believe that for the most part television audiences are not accustomed to too great a change, and that they should be weaned gradually from standardized techniques.32

As this letter suggests, They Shall Be Heard was experimenting with a discussion format that was controversial in the early history of television.

The production strategies and set design of They Shall Be Heard also emphasized discussion as the most important theme of the show. The show opened with an announcer introducing the program over filmed footage of crowd scenes in different countries. As these international scenes faded out, the camera focused on the group of students seated in a tight semicircle on chairs, stools, and the floor in a living room setting.33 Regarding this arrangement, one student wrote to Fagan to complain that the participants were “packed together” and that those who sat on the stools sometimes felt awkward because they did not know what to do with their hands. Fagan replied that the students were seated closely together so that as different students spoke, the crew could quickly shift the camera and microphones.34

The show’s living room setting and seating arrangements are notable for two reasons. First, many scholars have written about how television producers constructed programs around an imagined nuclear family in a home setting.35 They Shall Be Heard borrowed the image of a living room, but rather than a breadwinning father and homemaking mother, the program filled the space with teenagers. Bandstand, in contrast, combined two popular teenage spaces, the gymnasium and the record shop. And unlike Bandstand host Bob Horn, who stood at a podium and came across as an easygoing school principal and a disc jockey, Fagan, in his role as moderator, sat off camera until the final wrap-up. While this arrangement aligned the viewer with both the camera and the moderator, in focusing almost exclusively on teenagers, They Shall Be Heard reworked a setting that was fast becoming a familiar television design. Second, in terms of seating, the technological limitations of early television (e.g., the large immobile cameras and crane microphones) actually promoted the physical proximity that the producers desired. It helped the Fellowship Commission to literally bring together young people from different racial, religious, and national backgrounds.

Through the production techniques of studio audience participation, seating arrangements, unscripted segments, and close-up shots, Fagan emphasized the spontaneity of live television on They Shall Be Heard. As media scholars like Jane Feuer and Rhona Berenstein have examined, television producers and performers have consistently emphasized the medium’s liveness, immediacy, and intimacy.36 For Fagan and the Fellowship Commission, the spontaneity of live discussion was central to They Shall Be Heard’s pedagogical potential. During the warm-up session, Fagan’s Fellowship Commission colleague Max Franzen explained, “students are acquainted with the procedures of the program and begin to explore some of the points of the particular subject. We try not to exhaust the discussion during the warm-up period but try to discover the points on which the students are conversant and have ideas.” Franzen hoped that this method would produce “spontaneity rather than ‘conditioned’ responses.”37 One teenage participant appreciated this plan, writing “I believe that your plan of not telling the participants exactly what they will discuss, although it adds to their nervousness, assures the onlookers that the views expressed by the speakers are unbiased.”38 In addition, a participant from West Catholic High School offered that he “liked the way in which the show was presented without scripts since it gave the teenagers a chance to state their opinions on topics which directly concern them.”39

FIGURE 10. Teenagers participating in discussion in the living room set on They Shall Be Heard. Maurice Fagan, seated with his back to the camera, tried to downplay his role as moderator. 1952. Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, PA.

In this format the discussion sometimes strayed from the topic, a point that drew a letter of complaint from the editor of Exhibitor magazine. In his reply, Fagan justified this discussion technique, arguing “It seems to me that many important ideas were advanced by the youngsters even though the discussion might not have had the well-rounded, pat character of rehearsed programs or programs where the youngsters were primed in advance with the wisdom of others.” “Would you agree,” Fagan asked, “that even if the end result is not a polished intellectual one that the basic purpose of presenting fresh, uncoached viewpoints is in itself a contribution of the first order?” Among the show’s contributions, he argued, was that it enabled the “public [to] see ‘how youngsters think’ rather than just ‘what they think.’ ” 40 For Fagan, the live televised discussions gave teenagers a chance to think through issues and express their ideas, and offered viewers a chance to see the thought processes in action. In both cases, They Shall Be Heard used spontaneity to address viewers as citizens and create the possibility for pedagogy through discussion.

Bandstand also emphasized the spontaneity of live television, but it did so to encourage viewers to develop a participatory consumer relationship with the program. Bandstand addressed viewers as part of a club that came together every afternoon to share in the consumption of music and sponsors’ products. The teens in the studio influenced, and stood in for, the thousands of other teenagers watching the live program at home in the WFIL–adelphia region. In contrast to the discussions They Shall Be Heard encouraged, Bandstand emphasized the opinions of teenagers as a form of market research. Individual teenagers expressed their opinions of a given song or performer during the rate-a-record segment, while the studio audience registered its group opinion through the level of energy in dancing or applause. Appropriate to the show’s focus on music and dancing, the studio was not designed for periods of sustained talking. In this way, Bandstand situated studio audience members as consumers and addressed its television audience in the same way.

The producers of They Shall Be Heard and Bandstand tuned their respective modes of address to adults as well as teenagers. In the case of They Shall Be Heard, the show aired Friday mornings at 10:30 A.M. during its first two months, a time at which most teenagers would be in school. Thanks to the school board’s radio and television department’s participation in the production, the program was listed for in-school viewing. Many schools did not have televisions, however, and individual teachers could decide whether to include the program. One of the participants on the show commented on this problem in a letter to Fagan “I think it would be better if the program could be seen by the girls and boys whom it would concern. That’s all of us. They can’t see it, so there isn’t much sense in giving helpful solutions to problems. I think it would be better if it was held about 4 o’clock in the afternoon.”41 In his reply, Franzen assured the student that people were watching the show:

I don’t think you need to feel discouraged about the program not reaching people who will be helped by the ideas that the students have. We know there are many school classes that have the opportunity to tune in the program every Friday morning since it is listed by the public school system for in-school listening. We are even more thrilled to be able to reach parents, since we believe that the ideals, ideas and thinking of young people have an important effect on them.42

In December 1952, the producers’ optimism about the audience increased when WCAU moved the show to a more coveted time slot, Sunday afternoons at 2:30 P.M., because WCAU thought it was a “strong program for family listening hours.”43 Fagan expressed his enthusiasm for this new time in a letter to a former participant of the show: “We are very pleased to be able to reach a much larger audience, particularly more young people who will be able to see it at that hour.”44 In a letter to WCAU staff, Fagan also noted that in providing an opportunity for “family units” to view the program,

[they] were correcting one of the major weaknesses of many intergroup relations programs. That weakness is that the children are reached separately from their parents instead of simultaneously and thus some children may develop a smug or superior attitude and may even clash with their parents about particular issues. Family listening permits the adults and youngsters to view together and discuss together, to grow together.45

While the Fellowship Commission believed that young people held more malleable views on race and presented the most open audience for antira-cist messages, it viewed parents as important influences on teenagers’ racial attitudes, and believed that reaching both teens and adults together as citizens was a critical part of They Shall Be Heard’s goal of fighting prejudice.

Adults also made up a key portion of Bandstand’s television audience, but in this case parents figured as consumers of the show’s entertainment and advertising rather than as local neighbors and citizens. The 1955 Bandstand yearbook, for example, depicts different family combinations in front of a television console under the heading, “The family enjoys ‘Bandstand’ at home, too.” The yearbook continues:

Whether young-in-age or young-at-heart, “Bandstand” viewers at home are just as ardent fans of the program as the teenagers dancing “On camera” in the studio. … In fact, the program is so popular that Mom finds it difficult to leave the TV set when she’s doing the family ironing. … Even Dad (if he’s lucky) gets to enjoy the show, too, as sign-off isn’t until 5 P.M.46

In the course of one paragraph, the yearbook assured potential advertisers that in addition to a devoted teenage following, Bandstand’s television audience included a profitable number of adult viewers. In this image of the audience, the yearbook called upon gender norms in relation to television viewers (e.g., the young housewife watching television while performing domestic chores in the home, and the father coming home from work early to sneak a peak at afternoon programming) that were a common trope for television producers and commentators in this era.47 When Bandstand’s producers prepared to pitch the show to ABC for national broadcast in 1957, they continued to emphasize the profitability of these additional adult viewers and consumers.48

On May 10, 1953, after a twenty-seven-episode run, They Shall Be Heard went on summer hiatus. This happened in part because of the difficulty of getting students during the summer, but more so because WCAU aired Philadelphia Phillies baseball games in the afternoons during the summer months. In the spring of 1953, Franzen expressed hope that the station would be interested in resuming the program in the fall.49 To encourage WCAU to resume the program, Clarence Pickett, the president of the Fellowship Commission, wrote directly to the station president. After thanking him for the valuable airtime and production assistance, Pickett detailed the contributions WCAU made by airing this series:

First, a unique TV discussion format was developed. Second, it was a fine example of the cooperative efforts of the principal educational agencies of our city. Third, many boys and girls from different walks of life were given an opportunity to meet and consider current problems together. Fourth, it was a courageous presentation of significant educational material. And finally, as far as our own particular field is concerned, the program made a significant contribution to intergroup understanding.50

Pickett sent similar letters to the superintendents of the school systems and stressed the importance of cooperation among the public, private, and diocesan schools.

Just before the start of the 1953 school year, Fagan followed up on Pickett’s letter by writing to Margaret Kearney at WCAU. Fagan reiterated the contributions of the show and emphasized the importance of broadcasting contentious intercultural education topics. “It took courage,” he wrote, “for you and WCAU to risk a program which treated such highly controversial matter and which risked presentation with so little rehearsal.” Fagan also reminded Kearney that the Fellowship Commission had cooperated with WCAU to minimize the potential controversy in the discussions:

[I]n each of our planning periods you emphasized the need for sympathetic presentation of the viewpoints to be criticized so that the appeal of the program would be “to see the light” rather than to read out of society those who were unable so far “to see the light” as we think it should be seen. Thus, strongly antagonistic opinions were presented in a friendly, democratic spirit and the young people obtained experience in how to differ without being disagreeable. They also learned the importance of getting as many viewpoints as possible before making up their minds.51

Despite these appeals, the show did not return to WCAU in the fall of 1953. Most likely, as television airtime had become more profitable, WCAU elected to reduce its voluntary cooperation with the school system, or shifted its goodwill time to the less lucrative late morning or early afternoon weekday hours. In addition, the policy of the schools’ television broadcasting department, which distributed evaluation reports to the schools for comments and suggestions on programs, was to “plan series which will be acceptable to all the school systems receiving them for in- school viewing.”52 As such, pressure not to renew They Shall Be Heard might also have come from school personnel who vetted the school television lineup. In either case, after They Shall Be Heard was canceled, the broadcasts produced in cooperation between the city’s commercial television stations and the schools were more didactic, featuring science, language, and musical instruction.

Philadelphia’s school television program remained the largest in the country and was in its sixth year when They Shall Be Heard debuted. The schools continued to produce or coproduce fifteen television shows, including R Is for Rhythm, a music presentation for grade school students, and How Is Your Social IQ? an etiquette program aimed at high school girls.53 The Fellowship Commission, however, no longer played a role in these productions, and none of the broadcasts broached potentially controversial topics.

In addressing their respective viewers as consumers and citizens, Bandstand and They Shall Be Heard were a small part of larger struggle over how consumership and citizenship would be related in the postwar era. Historians Lizabeth Cohen and Charles McGovern have suggested that American identities as “citizen” and “consumer” became linked in the decades before World War II.54 Organized consumer movements pushed policy makers to see participation in the consumer economy as an essential part of full citizenship. “By the end of the depression decade,” Cohen notes, “invoking ‘the consumer’ had become an acceptable way of promoting the public good, of defending the economic rights and needs of ordinary citizens.”55 In the postwar “consumers’ republic,” Cohen argues, this connection of citizenship and consumership underscored a belief that a prospering mass consumption economy could foster social egalitarianism and democratic participation. Private consumption became equated with civic duty itself and shaped many parts of postwar American life. Backed by federal policies and public and private investment, these consumer desires shaped where Americans lived, shopped, and went to school.56

Bandstand’s model of teen television, one focused on the purchasing power of youth, fit neatly into the ethos of postwar consumer citizenship. Bandstand invited viewers to the new Main Street of WFIL–adelphia to participate in a consumption community every afternoon. Bandstand reminded viewers they were part of this community by repeating the names of the neighborhoods, cities, and towns represented in the studio audience and television audience. This community, however, did not ask viewers to do anything beyond continuing to watch the show and purchase the sponsors’ products. Bandstand expanded on this shared experience of consumption to become a national commercial success as American Bandstand.

The Fellowship Commission, in contrast, wanted They Shall Be Heard to be a “public sphere,” a space in which to stimulate debate and influence public opinion.57 Specifically, the Fellowship Commission hoped to increase support for its civil rights message and to persuade viewers to reject racial prejudice and discrimination in housing, education, and employment throughout Philadelphia. The Commission never believed that a television show could resolve all of these problems, but it thought that giving teenagers an opportunity to participate in public discourse on community relations was one way to influence the opinions of people in neighborhoods experiencing changing racial demographics.

Bandstand’s model of teen television emerged victorious, in large part, because federal broadcast policy gave advertising-supported programs an advantage over civic-oriented shows. As a result, Bandstand broadcast for ten hours a week to the four-state WFIL–adelphia area, whereas They Shall Be Heard relied on a system of voluntary cooperation to access the airwaves for just one hour a week. Bandstand and They Shall Be Heard illustrate, in microcosm, how television contributed to the elevation of consumer culture over civic life.

They Shall Be Heard broke new ground in the field of intercultural education and was among the Fellowship Commission’s most innovative attempts to counter racial prejudice in Philadelphia. They Shall Be Heard’s cancellation dealt a blow to the Fellowship Commission’s antidiscrimination work, but the group redoubled its efforts to improve race relations and end educational inequality in Philadelphia’s public high schools. As chapters 3 and 4 show, Maurice Fagan, black educational activist Floyd Logan, and other civil rights advocates confronted the expansion of de facto school segregation. These activists faced the challenge of making de facto school segregation a visible issue in Philadelphia, a challenge compounded by the loss of a television forum like They Shall Be Heard in which to articulate these concerns.