What has been called by certain groups “de facto segregation” in some schools has not been the result of policy by The Board of Public Education. [T]he record of the progress of the Philadelphia Public Schools in the integration movement is among the best, if not the best, of those of the great cities of the Nation.

—Allen Wetter, Superintendent of Philadelphia Schools in “For Every Child: The Story of Integration in the Philadelphia Public Schools,” October 1960

When the Philadelphia School Board published “For Every Child: The Story of Integration in the Philadelphia Public Schools” in 1960, it was the latest and most public rejoinder to the civil rights advocates who criticized the board for failing to address school segregation throughout the 1950s. As school officials continued to issue statements of their progress on integration, however, the city’s public schools grew more racially segregated. Philadelphia illuminates the dilemma posed by de facto school segregation. While many educational activists used the term de facto segregation to describe the discriminatory practices of schools outside the South, for school board officials de facto meant that segregation was the product of market forces and private decisions beyond their control. Casting de facto segregation as “innocent segregation” allowed school officials to claim that they had no legal responsibility or power to address it.

The de facto dilemma—visible school segregation with no means of legal redress—became the defining challenge for civil rights advocates in the North, Midwest, and West in the 1950s and 1960s. As in Philadelphia, educational activists in Boston, Chicago, Milwaukee, New York, and other cities fought recalcitrant school officials to secure equal education for black students.1 In the 1960s, the de facto dilemma also emerged as the dominant roadblock to school integration in the South. While school segregation has traditionally been understood through the dichotomy of de facto and de jure segregation, recent work on Charlotte, Atlanta, Mississippi, and other southern locales suggests that a broad spectrum of white politicians, school officials, and grassroots parents groups took up the language of de facto segregation to justify their inaction on school integration.2 Rather than public displays of massive resistance, these southern moderates and elites voiced rhetorical support for integration and allowed token black students in white schools, but opposed the methods necessary to integrate schools. The de facto explanation crossed regional lines, providing opponents of school integration a color-blind rhetoric to defend the continuation of segregated education.

Historian Matthew Lassiter describes this de facto rational as the “suburban blueprint on school desegregation” that emerged in the late 1960s.3 In this view, private housing choices caused segregated schools, and any resulting racial inequality was beyond the scope of governmental responsibility. This way of explaining away school segregation ignored the role of government agencies in supporting residential segregation, as well as the role of school zoning polices and construction practices in creating and maintaining segregated schools. Since the 1970s, the Supreme Court and many lower courts have embraced this view of schools as innocent victims of natural residential segregation, adopting what American studies scholar George Lipsitz calls an “epistemology of ignorance” dependent on the distortion, erasure, and occlusion of the clear and consistent evidence of racially discriminatory policies in education.4 The de facto rationale, therefore, came to justify a theory of white innocence with regard to school segregation. While the de facto rationale eventually undercut desegregation efforts across the country, educational activists in Philadelphia were among the first to encounter the dilemma it posed.

Unlike other case studies of de facto segregation, Philadelphia was also home to American Bandstand, and the city provides a unique example of how schools and television articulated similar visions of segregated youth culture. For black teenagers and civil rights advocates, the city’s public schools, like Bandstand, became sites of struggle over how to prove and overturn racially discriminatory policies. In their differential treatment of black students and their denial of charges of discrimination, the Philadelphia school board’s policies resembled those of Bandstand’s producers. Bandstand’s producers, for example, insisted that the show’s admissions policy was color-blind, while the school board embraced antidiscrimination rhetoric without committing itself to affirmative steps towards integration. This rhetoric obscured the fact that Bandstand consistently excluded black teens from the show’s West Philadelphia studio and the school system tracked black students into lower-level curricula. Moreover, while Bandstand’s producers took the segregationist side of neighborhood fights over integration in order to present a safe image of youth culture to advertisers, the school board contributed to these neighborhood racial changes only in one direction by building schools in areas that exacerbated de facto school segregation. If Bandstand made television an important site of struggle over segregation and the representation of youth culture, Philadelphia’s civil rights advocates made public schools sites of struggle over segregation and the daily experiences of young people.

The fight against Philadelphia’s school segregation gained momentum in the 1950s thanks to Maurice Fagan of the Fellowship Commission and Floyd Logan of the Educational Equality League. Fagan served as the executive director of the Fellowship Commission, Philadelphia’s leading interracial civil rights coalition, and was a major figure in the city’s Jewish civil rights community. Fagan was part of a generation of Jewish community workers who turned to intergroup relations as a tool to fight prejudice and keep postwar anti-Semitism at bay.5 Logan founded the Educational Equality League with fifteen other black citizens in 1932 at the age of thirty-two and was Philadelphia’s leading advocate for black students and teachers in the public schools in the 1940s and 1950s. In attempting to reform education in Philadelphia, where the school board was largely isolated from political debates and public opinion and educational issues received little newspaper coverage, Fagan’s and Logan’s first challenge was to make educational discrimination an issue that resonated with citizens beyond the neighborhood level.6 Fagan worked to make Philadelphia a focal point for a national network of social scientists interested in prejudice and race relations. He implemented the work of social scientists such as Gunner Myrdal, Kenneth Clark, and Gordon Allport at the grassroots level by partnering with school officials to distribute an array of antidiscrimination education materials. His commitment to addressing prejudice at an individual level, however, prevented Fagan from working to change the school policies that contributed to de facto segregation.

While Fagan attempted to draw national attention to Philadelphia and introduced the language of intercultural education into the school curriculum, Logan used the schools’ antidiscrimination rhetoric to call attention to the persistent discrimination against black students in the city’s schools. Logan’s educational activism took many forms: he investigated individual cases of discrimination on behalf of students and teachers; he collected information on school demographics and facilities to demonstrate inequality; he pushed the school board to take an official position on discrimination and segregation; and through his public letters and reports he served as an unofficial reporter on educational issues for the Philadelphia Tribune, the city’s leading black newspaper. As the civil rights movement gained national attention, Logan also used events like the Little Rock school integration crisis to call attention to Philadelphia’s school segregation and educational inequality. Logan’s research and accumulated records on discrimination in the public schools also provided the base of knowledge that the local NAACP branch and other civil rights advocates used to escalate the school segregation issue in the early 1960s. Confronted by Logan and his fellow educational activists, the school board pointed to its adoption of the intercultural educational materials provided by Fagan and the Fellowship Commission as evidence of antidiscrimination progress. The school board played the city’s civil rights advocates against each other, adopting the language of intercultural education and declaring success on the question of integration to avoid making the tangible policy changes that would promote integration. Logan’s struggle to prove the existence of school discrimination and the school board’s manipulation of Fagan’s intercultural educational achievements highlight the difficult challenges northern civil rights advocates faced in fighting school segregation.

Set against the backdrop of persistent employment and housing discrimination, schools were not a top-tier issue for most of Philadelphia’s civil rights advocates in the 1950s. Breaking racial barriers in the labor and housing markets required considerable resources, and despite making slow and fitful progress on these fronts, the outlook for addressing school discrimination was even less promising. The challenge of fighting discrimination in the schools stemmed largely from the institutional inertia of the city’s school board. Many historians have argued that Progressive Era campaigns to “take the schools out of politics” were veiled attempts by elites to take control of school boards away from the ethnic and working-class communities that controlled urban boards in the early twentieth century.7 While Philadelphia was part of this larger trend, its school board was even more removed from community groups and voters than in other major cities. Unlike cities in which school board members were selected by mayors or chosen in elections, Philadelphia’s fifteen-member board of education was selected by a panel of judges, and members could be reappointed for six-year terms as long as they chose to serve. In New York, Chicago, Baltimore, and San Francisco, mayors appointed school board members, while in Los Angeles, Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, and Boston members were selected in nonpartisan elections. Only in Washington, D.C., and Pittsburgh, among other major cities, were school boards appointed by a panel of judges as they were in Philadelphia.8

In practice, the panel of judges appointed candidates selected by the city’s political parties, alternating between Democratic and Republic appointees. Although members were nominally independent from political influence, a 1967 study by City University of New York researchers contended that the school board was “conservative and closely aligned with the city’s political leadership” and included “members of the Philadelphia business community who were less concerned with educational policy than they were with avoiding controversy and limiting school expenditures to acceptable levels.”9 School district business manager Add Anderson supervised these expenditures and pleased both political parties by keeping school tax increases as low as possible. Anderson controlled more than two hundred patronage jobs and wielded enormous influence until his death in 1962.10 The school board setup also insulated the district from investigations by the Commission on Human Relations (CHR), the city’s discrimination watchdog group, and isolated the schools from public opinion during Philadelphia’s era of civic reform in the early 1950s.11 “The board is a removed aristocracy, twice removed from popular control,” CHR chairmen George Schermer told a reviewer from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 1962. “Its members sit on Olympus, insulated by a board of judges, and insensitive to the popular demands of the school public.”12 A civic groups’ description also conveyed the school board’s secrecy and insularity:

The afternoon meetings of the Board of Public Education in Philadelphia are formal and brief, and attendance by the public is limited. Decisions are reached in executive session; discussions of programs rarely take place in public view although wide differences of opinion exist among board members on some issues. The printed minutes of the Board’s meetings contain routine administrative details. In one recent instance where controversy erupted in a public meeting of the board, all reference to the dispute was further expunged.13

All of this made the work of civil rights advocates who prioritized the issue of discrimination in schools, like Fagan and Logan, more urgent and difficult.

Confronted with a school board isolated from the daily experiences of the city’s students and parents, Fagan worked to strengthen the Fellowship Commission’s relationship with the schools in order to implement intercultural educational materials and programs into the curriculum. The Fellowship Commission’s relationship with the school system dated back to the Commission’s founding in 1941. The first chairman of the Fellowship Commission, William Welsh, was also an assistant superintendent of schools, and Fellowship Commission vice chairmen Tanner Duckrey served as an assistant to the Department of Superintendents, the first African American to serve in this capacity.14 The Commission started its first school project in September 1944. In this Early Childhood Project, the Fellowship Commission worked with the public schools and consultants from the Bureau for Intercultural Education, a national organization of progressive educators led by William Kilpatrick of Columbia University. The Fellowship Commission and the Bureau for Intercultural Education sought to find a scientific basis for showing that children’s attitudes could change, and that teachers who were not experts in intercultural educational methods could help bring about this change.15 The results of this research were published in 1952 in They Learn What They Live, the eighth in a series of ten books produced by the Bureau on Intercultural Education from 1943 to 1954 in its Problems of Race and Culture in American Education series.16

The Early Childhood Project received attention in education journals, as well as in Philadelphia newspapers and national newspapers and magazines. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin praised the research for offering “concrete, scientific proof that brotherly love isn’t a nebulous out-dated ideal, not even in these tense times.”17 The New York Times called the project “pioneer research” that revealed that young children bring to school “definite feelings about race, awareness of religious differences and of the significance of ‘we’re rich’ or ‘they’re poor.’” 18 More important, the Early Childhood Project helped to establish Philadelphia as a leading national site for intercultural education, and it helped the Fellowship Commission solidify its friendly working relationship with the school system. By 1947, George Trowbridge, chairman of the Fellowship Commission, told those gathered at the annual meeting that “Undoubtedly the most encouraging evidence of successful results in 1946 is to be found in our relationships with the Philadelphia School System.”19 Between the completion of the project in 1948 and the publication of the final report in 1952, the Fellowship Commission continued to strengthen this relationship by organizing intercultural leadership seminars for teachers, principals, and parents and by developing new intercultural education materials as curriculum supplements.

Building on the positive reception to the Early Childhood Project from educational scholars across the country, Fagan believed that this national community of social scientists could be the key to addressing discrimination in Philadelphia’s schools. To this end, Fagan dedicated a majority of his time between 1952 and 1954 to developing an ambitious Ford Foundation proposal he believed would further establish Philadelphia as a leader in antidiscrimination education. The proposal called for a thirteen-year plan in which the Fellowship Commission would work with a group of leading social scientists to use Philadelphia as a “laboratory on intergroup relations.” The Fellowship Commission proposed to establish eight field offices to study community relations in segregated and integrated neighborhoods. In the central component of this study, human relations experts would follow young people in different neighborhoods from kindergarten through high school. They hoped to examine the development of intergroup attitudes, including whether and how intergroup contact in neighborhoods affected the intercultural education being offered in the schools. Fagan and his colleagues also hoped to use the grant to experiment with new uses of television, building on their teenage television program They Shall Be Heard, to “personalize” intercultural education messages.20 Although the Ford Foundation rejected the six-and-a-half-million-dollar proposal, the request clearly outlines the Fellowship Commission’s thinking on intercultural relations in this period.21 In its focus on ascertaining and changing prejudiced attitudes, the Fellowship Commission’s approach to this study mirrored the work of academics who, in the wake of Gunner Myrdal’s An American Dilemma (1944), published widely on prejudice and social relations, including publications that influenced the Brown decision.

Myrdal’s thirteen-hundred-page book argued that racism contradicted America’s democratic ideals and that the racial dogma that supported racial oppression could be uprooted through education. The Carnegie Corporation, the project’s sponsor, had previously paid little attention to domestic race issues, focusing instead on financing educational projects in British colonies in Africa.22 Carnegie trustees proposed a study of the “Negro problem” in 1935 largely out of concern for rising racial tensions.23 They picked Myrdal, a Swedish economist with little familiarity with American race relations, to bring an “entirely fresh mind” to the subject. For Carnegie Corporation president Frederick Keppel, this meant breaking with both the “old regime of the South” and the “traditions of the abolitionist movement.”24 Following this directive, Myrdal presented facts about racial violence and oppression in a way that would be palatable for the broadest possible audience. “Myrdal’s genius,” sociologist Stephen Steinberg argues, “was to dispense only as much medicine as the patient was willing to swallow.”25 Myrdal’s book was politically safe because he emphasized moral persuasion rather than specific policies or legislation to challenge racial structures. While Myrdal’s anti-prejudice framework helped to delegitimize racism, An American Dilemma also obscured frameworks for understanding racism as a result of structural power inequalities.

In contrast, African American historian Rayford Logan (no relation to Floyd Logan) edited What the Negro Wants, a collection of fourteen essays including contributions from W. E. B. Du Bois, A. Philip Randolph, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Langston Hughes. Published the same year as An American Dilemma, the essays in What the Negro Wants focus on the need for African Americans to push for full economic, political, legal, and social equality. These opinions were initially deemed too controversial to print by the editor who commissioned the study. After Logan threatened to take the manuscript to another press and consult an attorney, the editor agreed to publish the book, provided that it contained an introduction disassociating himself from the essays. “What disturbed Mr. Couch [the editor] more than anything else,” Logan later wrote, “was the virtual unanimity of the 14 contributors in wanting equal rights for Negroes.”26 Logan’s contribution to the collection, “The Negro Wants First-Class Citizenship,” clearly outlined six fundamental civil rights demands: “Equality of opportunity; Equal pay for equal work; Equal protection of the laws; Equality of suffrage; Equal recognition of the dignity of the human being; and Abolition of public segregation.”27 Unlike Myrdal, Logan and his fellow essayists framed racism in terms of power and the unequal allocation of resources and life chances. They welcomed education and moral persuasion as tools to fight prejudice, but recognized that these tools alone were insufficient in fighting structural racism. What the Negro Wants influenced postwar civil rights activists, but it lacked both the Carnegie Corporation’s prestigious imprint and the politically safe message that helped to elevate An American Dilemma. Myrdal’s anti-prejudice framework became the dominant model for understanding racial problems in this era, and his book shaped the way many political leaders, courts, journalists, and local organizations like the Fellowship Commission talked about racism.28

Working in the shadow of Myrdal, Fagan hoped to use social science methods to move beyond “trial and error” approaches to antidiscrimination work by establishing a “sound and scientific basis” for a new “science of intergroup relations.”29 Not coincidentally, several professors of psychology and sociology reviewed drafts of the Fellowship Commission’s Ford Foundation proposal and submitted letters of support for the project, including Otto Klineberg and R. M. MacIver of Columbia, Ira Reid of Haverford College, and Gordon Allport of Harvard University, who called the proposal “brilliant and audacious.”30 In submitting this proposal, the Fellowship Commission believed that Philadelphia could provide a model for other cities to follow in dealing with rapidly changing neighborhoods and schools.

Yet while the Fellowship Commission was drawing up plans to use Philadelphia as a national laboratory for community relations, the city’s schools grew more segregated. The tension between the Fellowship Commission’s ambitions and the city’s changing educational situation came out in the group’s first meeting to discuss the Ford proposal. Florence Kite, a Society of Friends representative on the Fellowship Commission, questioned Fagan about the intercultural school programs he hoped to make citywide. “What is the point of working on an intercultural human relations program in the high schools … when some of our local Philadelphia high schools are segregated?” Kite asked. Kite further questioned Fagan about the utility of intercultural programs “when there is no opportunity for the students to meet other students who are not of their own group, within a given high school.” Fagan replied:

Both programs are important, the one of breaking down the pattern of segregated schools where they exists [sic], and, at the same time, affording opportunities in the interim for students from such a homogenous school to mix with students from other groups in such organizations as High School Fellowship, for example. We must find some way of doing both at the same time—for we dare not abandon either approach.31

Fagan argued for this dual approach in 1952, but through the mid-and late 1950s the Fellowship Commission dedicated more resources to, and had more success with, its intercultural education programs. Fagan and the Fellowship Commission illustrate, at a local level, the limitations of focusing strictly on education to eliminate prejudice. The Fellowship Commission’s strategic decision to focus on prejudiced attitudes rather than the school board’s zoning or building policies meant that the burden of fighting de facto desegregation in the city’s schools fell almost entirely to Floyd Logan.

While Fagan and the Fellowship Commission worked to make Philadelphia a locus of activity for intercultural educators, Floyd Logan was almost two decades into his work on behalf of black teachers and students. Born in Asheville, North Carolina, Logan attended segregated schools from elementary school through high school. Logan moved to Philadelphia in 1921, where he worked with the U.S. Customs Bureau and later the Internal Revenue Service. In 1932, Logan and fifteen other black Philadelphians founded the Educational Equality League (EEL) with the goals of obtaining and safeguarding “equal education opportunities for all people regardless of race, color, religion, or national origin” and bringing “about interracial integration of pupils, teachers, and other personnel.”32 Logan worked on the issue of employment discrimination against teachers through the late 1930s and the 1940s, and although progress was slow, he helped to secure the merger of racially segregated teacher eligibility lists and helped a small number of black teachers make inroads into junior and senior high schools.33 During this time, Logan was the EEL’s president, spokesman, and chief researcher, and he dedicated himself full-time to this unpaid work when he retired with a government pension in 1955.

Working from his home in West Philadelphia, Logan wrote thousands of letters requesting statistical information from the school board, notifying school and city officials of discrimination encountered by black students and teachers, and reminding officials of promises and policies they had failed to implement.34 Logan worked occasionally with the Fellowship Commission, the NAACP, the Urban League, and other civil rights advocates, but he was the only one who dedicated himself fulltime to educational issues. Logan’s work on behalf of black students in these years reveals the inequities of a public school system that, as a result of discriminatory housing practices, the school board’s school construction decisions, and the school board’s unwillingness to implement affirmative policies for integration, grew more segregated throughout the decade.

Logan first turned his attention to the segregation of students in public schools in November 1947 when he called the first of two conferences with leaders of local civil rights organizations, including the Philadelphia NAACP, the Philadelphia Council of Churches, and the National Conference of Christians and Jews. The members met with school officials to express their “deep concern over the alarming growth of predominant[ly] colored schools in Philadelphia.” They also discussed possible legal suits “testing the legality of the practice of segregation on the basis of race in our public schools,” but they did not make any progress on this front in the subsequent three years.35 In early 1951, however, Logan seized on a visiting committee’s report on the majority-black Benjamin Franklin High School to lobby for the replacement of its outdated facilities and limited curriculum. In taking up this high school case, Logan addressed the educational level in which black students encountered the widest spectrum of educational discrimination.

Between 1900 and 1950, high school enrollments increased dramatically. Nationally, the percentage of fourteen- to seventeen-year-olds in high school grew from 10 percent in 1900 to 51 percent in 1930 and to 76 percent in 1950. Graduation rates also increased, with the percentage of seventeen-year-olds who completed high school rising from 6 percent in 1900 to 29 percent in 1930 and to 59 percent in 1950.36 These statistics, however, belie the disparities in the quality of education among Philadelphia’s high schools in this era. Among the city’s twenty-one high schools, for example, two were application-only academic high schools (Central High School of Philadelphia and Philadelphia High School for Girls), and three were vocational schools (Bok, Dobbins, and Mastbaum). In addition to these official designations, many schools held unofficial reputations related to the racial, ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic characteristics of their neighborhoods and student populations. These reputations were a mix of personal experience, anecdotes, and rumor, but they had real implications for the quality of education offered at different schools. As the U.S. Supreme Court found in Green v. New Kent County School Board (1968), racially identifiable schools, where residents knew which schools were “white” schools and which were “black” schools, were a barrier to a unitary school district offering real equality of opportunity.37 In Philadelphia, schools with bad reputations had difficulty attracting experienced teachers and therefore had a larger number of substitute teachers. These schools were also more likely to lose academically talented students who transferred to schools with better reputations. In addition, if the students who remained at these schools did not score well on IQ tests, administrators were more likely to follow the tenets of life adjustment education and assign students to modified nonacademic curricula. Given the discrimination blacks faced in the city’s housing market and the racial prejudice that informed the unofficial reputations of schools, black students were much more likely to attend high schools offering watered-down courses, such as Franklin.

Located in the lower North Philadelphia area, Franklin opened as an all-boys school in 1939. The school occupied a structure built in 1894 to house Central High School, one of the city’s two prestigious academic high schools, which moved to the Olney area above North Philadelphia in 1936. In the years after World War II, Franklin operated a daytime high school as well as an evening Veterans School, offering accelerated college preparatory courses and refresher courses for World War II veterans. This Veterans School enrolled more than ten thousand men and women from 1945 to 1955, half of whom continued on to college or technical school.38

The students attending Franklin during the day, over 95 percent of whom were black, were not as fortunate. While the school attended to the education of veterans, allocating school board funds to cover library materials and offer supplies not covered by the Veterans Administration, the regular day students attended one of the most poorly funded high schools in the system. In April 1951, a visiting committee from the Middle States Association of School and Colleges catalogued the shortcomings of the school. The committee members noted that Franklin had the worst attendance record in the city and that only 20 to 30 percent of the students who started school in tenth grade graduated. Although the visiting committee made few direct criticisms of the board, the members did criticize what they viewed to be the school board’s policy of grouping students with low IQ scores in one school.39 Logan raised this criticism throughout the 1950s, but the school board, following educational thought of this era, continued to place students in different curriculum tracks based on their IQ scores, junior high school grades, and teacher recommendations.

Illustrative of this educational practice at Franklin was Operation Fix-up. In this program, students went to an “outdoor classroom” built in an alley between row homes in South Philadelphia at Eighteenth and Cleveland Streets to learn about home repairs and home maintenance. With supervision and direction from the Redevelopment Authority and the Citizen’s Council on City Planning, the students helped to lay concrete, hang doors, and repair brick outhouses to be used as trash can shelters, among other tasks.40 Explaining the motivation for Operation Fix-up, Franklin principal Lewis Horowitz told the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin:

We realized that many of our boys would never learn about proper lighting, furnishing, sanitation and the like from their home surroundings. We also suspected that many had not the ability to become workmen in the skilled trades which required long years of training. So we decided to shift the emphasis in our instruction to make it more realistic.41

Horowitz’s belief in educating “nonacademic” students for the jobs available to them agreed with the tenets of life adjustment education, an outgrowth of the vocational education movement that enjoyed national popularity among high school educators from 1945 to the early 1950s.42 Historian Herbert Kliebard describes life adjustment education as conveying the “social message” that “each new generation needed to internalize the social status quo.”43 Indeed, with black students and workers blocked from the skilled trades because of discrimination in the school’s union-sponsored apprenticeship classes, life adjustment education reinforced discriminatory employment practices.44 At best, then, this education provided students with training for unskilled construction jobs. At worst, the program increased the education gap between these students and those at other high schools, while normalizing slum clearance and providing urban renewal interests with free labor. In either case, Franklin was unique among Philadelphia high schools in offering this curriculum option.

The poor conditions at Franklin did not come as a surprise to Logan or to black teenagers and parents in the Franklin school community. However, the Middle States report offered Logan an opportunity to bring more attention to the inequities of segregated education. Logan wrote letters to the Philadelphia Tribune and the Philadelphia Inquirer, and both papers ran articles quoting the visiting committee’s description of Franklin as a “Jim Crow school.”45 Building on this publicity, Logan next organized a conference on the “Democratization of Philadelphia Public Schools.” On October 15, 1951, forty civic and cultural organizations, including the NAACP, black fraternities and sororities, and the Jewish Community Relations Council, met at the Fellowship Commission building to discuss how to break down segregation in the public schools. Discussing issues of zoning, teacher placement, and curriculum, the groups started to draw up resolutions to present to the school board. Logan and his colleagues recommended that the board state its policy with regard to integration, that teachers be assigned based on qualifications rather than race, and that intercultural ideals expressed in curriculum publications be implemented in zoning and put into practice in the classroom. These recommendations remained the focal points of Logan’s work for the next decade.46

Only three days after these resolutions were drafted, an incident at West Philadelphia High School (WPHS) broadened the scope of Logan’s critique of the public schools and increased his sense of the urgency of bringing these policy recommendations to the board. The principal at West Philadelphia High School, George Montgomery, singled out the schools’ black students and blamed them for increased crime in the school and the city.47 At a pep rally before the afternoon football game the next day, black students, who made up 30 percent of the student body, protested the principal’s remarks by sitting silently. That same day, a group of parents met with the principal to discuss his remarks. Among these parents were Granville Jones, a black Democratic state representative whose three children attended WPHS, and the Reverend E. Luther Cunningham, the treasurer of the NAACP branch and a board member of the Fellowship Commission, whose daughter was present at the assembly. In addition to these black leaders, other parents sent letters of concern to Floyd Logan and the NAACP asking them to address this issue with the school board. “I have written to most of the papers and done all I can at the present,” one parent wrote. “This is not right because we help to pay [the principal’s] salary too. Is this supposed to be where all are created equal and where ours as well as theirs die in wars for this country?”48 On October 26, representatives of the NAACP and the EEL met the school superintendent Louis Hoyer. “In a very few moments [the principal] has created a segregated school. … He has set aside one group of the student body to be looked at with contempt as a [minority] group,” Walter Gay Jr., an attorney representing the EEL, told the superintendent.49 The Reverend Jesse Anderson, a member of the Fellowship Commission and the minister of the West Philadelphia Episcopal parish, pointed out the gap between the school board’s intercultural rhetoric and the principal’s comments. “A goodly segment of the authorities, principals and teacher of this school system … have been getting away with literal murder in their handling of minority groups,” Anderson said. “I fail to see how you reconcile the inept racial attitude and expression of the principal with the beautiful pamphlets entitled ‘Democracy in Action,’ ‘Living Together,’ and ‘Openmindedness.’ ” 50 Gay and Anderson concluded by asking for Montgomery’s resignation. Superintendent Hoyer said that he regretted the principal’s comments, but that he would need to meet with Montgomery before he could make a decision.

In November 1951, the education committee of the NAACP and the EEL met to develop a plan to rid Philadelphia schools of discrimination. On December 15, at a second meeting with members of the school board, the committee from the NAACP and the EEL offered a plan for improvements at WPHS. The committee requested that Montgomery be removed, citing a loss of confidence of parents, students, and the community. They asked that black teachers be integrated into the school’s all-white faculty. Arguing that the primary job of the public school was “to teach the children of all the people,” the committee also called for an end to watered-down classes for black students deemed by teachers to be “slum” children. Finally, the committee requested that specific steps be taken to improve “human relations” at WPHS, including in-service courses in intercultural education for administrators and teachers, community meetings for parents, adult education courses in intercultural education, the integration of black pupils into extracurricular activities at the school, and the organization of a fellowship club for students.51 As would become the pattern in the school board’s dealings with Logan, an official response was deferred until a later date.

Having not received a decision by the end of the 1952 school year, Logan appeared before the school board again on June 10. Gladys Thomas, the Philadelphia NAACP’s education director, and Dr. Marshall Shepard, a Baptist minister from West Philadelphia, represented the EEL. Logan reiterated the EEL’s requests for a policy on integration, for further integration of teachers at the senior high school level, and for zoning to promote desegregation. To emphasize his request that Franklin should be closed and replaced with a new building, Logan recounted that on a recent visit to the school’s auditorium, “it seemed more like the auditorium of a backwoods Southern school than part of a Philadelphia high school, and … the board should be ashamed to maintain a high school in that condition.” Moreover, he argued, bringing more equality to the schools would “deprive the Communists of their main source of propaganda and strength.”52 Following Logan, Shepard criticized the board for requesting more facts on discrimination in the schools, after Logan had already distributed a twenty-point list of statistics on segregation the previous year. “It [is] most unnecessary for us to tell the Board what it already [knows],” Shepard stated directly.53 Again, the board referred the EEL’s proposals to its policy committee for further study.

Following the meeting, Walter Biddle Saul, an attorney and the president of the school board, invited Logan and the other EEL members to an off-the-record conference with a smaller group of school officials. Saul opened the meeting by telling Logan that the EEL was wrong to refer to any schools as segregated schools. Saul further contended that “colored schools were such because of population,” that Logan “could not expect the schools to compel children to attend schools where they do not live,” that “state law requires the Board to accord to parents the right to send their children to schools of their choice,” and that many black parents favored having this option.54 Logan countered by arguing that Saul’s critiques did not meet the “serious study and consideration” promised by the board. Logan’s minutes from the meeting suggest that Saul conceded this point and appointed the school board’s policy committee chairwoman to study these “undemocratic problems” (Logan’s minutes also note the incongruity of Saul’s appointing a committee to study the problems that he had earlier declared not to exist).55 Before the close of the meeting, Saul stressed that he was opposed to the EEL’s publicizing these issues. Similarly, the school’s policy chairwoman said that the study would take at least four to five months, during which she hoped that her committee would not be under “too much pressure” from the EEL.56

While he waited for the completed report, Logan sent the committee more examples of discrimination in school zoning, classroom practices, and administrative appointments. After nine months, the school committee informed Logan that it had finished the report and invited him and other EEL members to a meeting on June 24, 1953. Logan later told the Philadelphia Tribune: “Though we were not overly optimistic of the investigation, we nevertheless felt that it would be at least fair.”57 After two years of waiting for the school board to take action on his evidence of discrimination in the schools, Logan was deeply disappointed with the report submitted by the committee. The report directly contradicted each of the points the EEL had raised: The school committee argued that the board’s teacher policies were in accord with the city’s Fair Employment Practices Ordinance, that there was no evidence of racial gerrymandering of district boundaries, that race was not a consideration in student transfers, and that white students were not transported by school bus to avoid majority black schools.58 After outlining these points, the committee went on to argue that the problem of integration was made “very much more acute and more difficult by the recent large Negro migration into Philadelphia,” and that black leaders had a responsibility to orient these “new Negro citizens to urban life and acceptable community behavior.” In addition to faulting black migrants for segregation, the school’s policy committee praised the school’s curriculum committee for undertaking “various projects to alleviate prejudice and neighborhood racial tensions through its courses on ‘Living Together’ and ‘Open-Mindedness.’” 59

For Logan, the problem with the committee’s report was that it was unwilling either to recognize the trend toward racial segregation in the schools or to recognize that the school board could take any steps to stem this trend. As Logan wrote to the chairwoman of the committee after the disappointing meeting, “we must sound a note of warning on the dangerous trend toward predominant and all colored schools. Many possibilities exist for reducing this trend and they should be explored. Specifically the Board must adopt a policy of planned mixing of as many students as population distribution will permit.”60 As he frequently did in his correspondence with school officials, Logan followed this recommendation with an appeal for the schools to live up to their antidiscrimination rhetoric. “Adoption by our Board of such democratic policies,” Logan wrote, “will put into practice our excellent intercultural courses [and in] this way we will be living ‘democracy,’ as well as teaching it.”61 As the school year began in 1953, Logan and his fellow educational activists in the EEL and NAACP finished a two-year encounter with the school board, in which time they saw little progress. Despite his frustration over the school board’s delays and refusal to address the policies that contributed to segregation, Logan continued to petition for an official policy on integration and pressed school officials to hold to their promise of building a new Franklin High School.

By 1953, the Philadelphia school board had crafted a solid defense for de facto segregation. First, it argued that segregated schools were the result of segregated housing patterns, over which it had no control. The naturalness of housing segregation became the centerpiece of the de facto rationale school officials in the North, Midwest, and West used to claim innocence with regard to school segregation. The de facto rationale replaced massive resistance in the South and has informed court decisions on school segregation since the early 1970s. This fiction of voluntary housing choice imposed an extremely difficult challenge for groups contesting school segregation. As desegregation expert Gary Or-field contends:

The school districts, which try to use housing as a justification for school segregation, often have the money to create what appears to be plausible evidence that local segregation is a product of choice by minority and white families, not discrimination. The plaintiffs usually lack the money to prove the history of housing discrimination. They cannot document the vicious cycles that led to those “choices.” They often lack the expertise to attack the validity of flawed survey data assessing the issues of guilt and remedy. Some courts adopt as facts what are speculative interpretations of misleading data used for inappropriate purposes.62

Although the NAACP did not file a lawsuit against school segregation in Philadelphia until 1961, Logan started gathering evidence in the late 1940s that he hoped would prove that racial segregation and unequal schools existed and were the result of official policy. Like Logan, educational activists in Boston, Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, and other cities faced off against school boards that maintained racial segregation while also denying its existence.63 The Philadelphia School Board thwarted the work of Logan and his fellow civil rights advocates by delaying action on proposals, holding off-the-record meetings, appointing internal committees to study the problem, and publishing reports that contradicted the evidence offered by critics.64 Outside the sight of the mainstream press and most citizens, these exchanges took place between a small group of school officials and the civil rights advocates who refused to let the issue be ignored. Without making any public statements favoring segregation, the school board honed a de facto rationale to avoid taking actions to integrate the schools.

In addition to holding up residential segregation to explain school segregation, the Philadelphia school board also argued that it was being especially proactive in creating better racial attitudes among its students. The schools’ anti-prejudice curriculum efforts, it argued, were far more progressive than those found in other cities and constituted a sufficient response to the racial change in the city’s schools. Here, the school board co-opted the antidiscrimination rhetoric that Fagan and the Fellowship Commission were working to implement. The ease with which the school officials embraced intercultural education and sidestepped integration highlights the limits of the Fellowship Commission’s educational approach to discrimination. As Logan made increasingly vocal demands for the school board to address school segregation, much of the Fellowship Commission’s energy went into the Ford Foundation proposal and related intercultural education programs. The Fellowship Commission assigned the task of developing a position on segregated schools to its Fair Education Opportunities Committee, headed by Nathan Agran of the Jewish Community Relations Council and Walter Wynn of the Urban League (the committee’s minutes note that Fagan attended the majority of the monthly meetings, but that Logan attended only twice in a three-year period). The committee dedicated meetings in January and February 1953 to the question of segregated schools, citing segregated housing and pupil transfers from “mixed” schools as primary causes.65 The committee only discussed the issue periodically over the next two years, focusing more attention on removing discriminatory quotas in college and professional school admissions, and later on pushing for a city community college.

Beyond allocating time to other forms of educational discrimination, the school board’s rejection of Logan’s proposals in 1953 influenced the Fellowship Commission’s shift of attention to admissions quotas. “The Executive Committee decided about two years ago to postpone approaches to the School System on the matter of ‘one-group’ schools,” Fellowship Commission chairman David Ullman noted in April 1955.66 Fagan and the other members of the Fellowship Commission were reluctant to jeopardize their close relationship with the public schools. When Fagan wrote to the new president of the school board Leon Obermayer in 1955 to request support for the Ford proposal, for example, he proclaimed that “The Fellowship Commission has demonstrated over the past fourteen years that it will not usurp the prerogatives of the educator and that it can be and is one of the staunchest champions of the School System.”67 While this approach allowed the Fellowship Commission to influence the classroom experience in many schools through intercultural education seminars and materials, it also meant that the largest civil rights organization in Philadelphia, during its most influential period, failed to address one of the most significant civil rights issues in the city. More insidiously, the school board took up the Fellowship Commission’s antidiscrimination language to reject Logan’s calls for an affirmative policy on integration. Even before the Supreme Court’s Brown decision led southern politicians and segregationists to develop their strategies for massive resistance, the Philadelphia school board used a combination of tactics to position itself as antidiscrimination while supporting policies that contributed to de facto schools segregation.

The school board’s refusal to develop a policy on de facto segregation was based on the claim that school segregation was a housing-related development beyond the board’s control. Despite this assertion, the school board’s construction decisions after World War II exacerbated segregation in the city’s schools and made Logan’s work even more difficult. Of the twenty-two new elementary, junior high, and senior high schools built after World War II, all but three were built in either new suburbanizing white neighborhoods on the city’s outskirts or in expanding black neighborhoods. As a result, school site selection was the determining factor in creating one-group schools that were almost all white or all black.68

These school placement decisions followed logically from governmental policies, initiated during the New Deal, that facilitated residential segregation in private and public housing. In Philadelphia’s private housing market, less than 1 percent of new construction was available to black home buyers in the 1950s.69 These racially distinct housing markets, supported by government dollars and abetted by the lack of federal and local antidiscrimination oversight on housing, provided the foundation for the de facto rational for segregated schools. White homeowners and renters who expected to live in racially homogeneous neighborhoods saw their preferences reflected in the school construction decisions. For black parents, new construction relieved school overcrowding, but given the school board’s history of second-class treatment of majority-black schools, siting schools in mostly black neighborhoods was a mixed blessing.

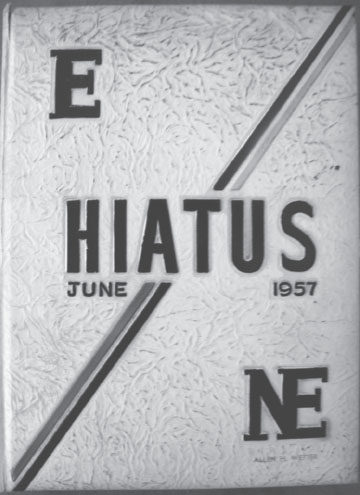

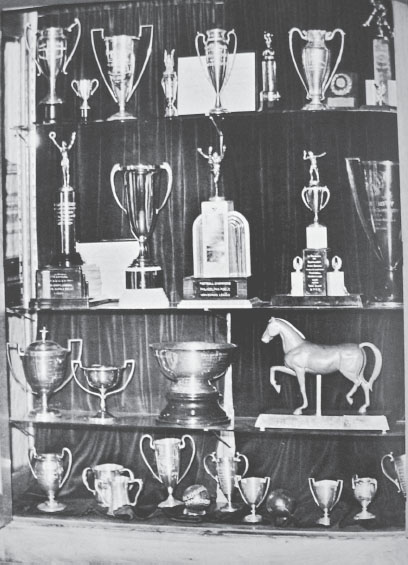

A leading concern for black parents and educational activists like Logan was that students at majority black schools would receive a lower quality of education than that available at majority white schools. Their concerns were well founded because the racial demographics of schools were an important factor in determining the curricular options available to students. The most glaring examples of the relationship among school construction, de facto segregation, and school curriculum are Northeast High School, Thomas Edison High School, and Franklin High School. The students at the all-boys Northeast High School attended one of the best public schools in the city. The school opened in 1905, but the school’s history dated to the 1890s when it operated as the Northeast Manual Training School. With a focus on engineering rather than a strictly academic curriculum, the school became the second most prestigious public school for young men in Philadelphia, trailing only Central High School.70 By the early 1950s, the school had a well-developed alumni network that raised money to provide college loans to students and awards for championship sports teams.71 In the fifty years since the school opened at Eighth Street and Lehigh Avenue in North Philadelphia, the racial demographics of the neighborhood changed from majority white to a mix of white ethnic groups and black residents. As a result, unlike many other schools in the city, Northeast’s student body in the mid-1950s was evenly divided between black and white students.

All of this changed in February 1957. Halfway through the school year, two-thirds of the teachers and a number of students left the school at Eighth and Lehigh for a new Northeast High in the fast-growing suburban neighborhoods at the edge of the city. The school board and Northeast’s alumni started discussing the new high school in the early 1950s, but for most of the teachers and students left behind at the old school (renamed Thomas Edison High School), the move happened abruptly. Almost overnight, the school’s name, most experienced teachers, and alumni network disappeared. The black and working-class white students who attended Northeast High School as sophomores and juniors in 1955 and 1956 were left to graduate from Thomas Edison High School when the new Northeast High opened in February of their senior year. The students left behind at Edison selected “hiatus” as their senior yearbook theme. This yearbook also showed that the new Northeast High secretively moved the school’s athletic trophies. While the yearbooks of the previous graduating class described the trophy case as “the symbol of the greatness of our school,” the “hiatus” seniors used before and after pictures of the full and empty trophy case to depict the loss of the most visible daily evidence of the school’s history.72

The Northeast section of Philadelphia expanded rapidly in the 1940s and 1950s, with new tract homes, shopping centers, and industrial parks replacing farmland. Almost all of the area’s population increase came from white families, many of whom moved from racially changing neighborhoods in other parts of the city. The Northeast’s small number of black residents lived in sections that dated back over a hundred years, but other black and Chinese American families who sought to move into the Northeast section were met with protests by white homeowners.73 Real estate agents turned away several black families who sought to move to Northeast neighborhoods in the late 1950s, claiming that they “were not accepting any colored applicants” or that they had been “instructed not to sell to anyone … that might disturb the neighborhood.”74 In addition, historian Guian McKee has shown how the Northeast benefited from Philadelphia’s industrial renewal program, which decentralized the city’s industry by building and renovating industrial areas. New industrial parks in the Northeast were not accessible by subway, trolley, or commuter rail, and McKee argues that “this orientation towards automobile transportation reinforced preexisting patterns of employment discrimination.”75 The racial segregation of Northeast High, therefore, followed housing and employment discrimination and was not the result of innocent private decisions.

FIGURE 11. The students who attended Northeast High School as sophomores and juniors were left to graduate from Thomas Edison High School when the new Northeast High School opened in February of their senior year. They selected “hiatus” as their yearbook theme. June 1957. Philadelphia School District Archives.

The case of Edison and Northeast reflected the growing divide between public schools in affluent neighborhoods and those in working-class and poor communities. Although both schools were technically in the same school system, Northeast represented a process of suburbanization within city lines. The U.S. Supreme Court ruling against cross-district metropolitan desegregation plans in Milliken v. Bradley (1974), and the continued defense of de facto segregation by courts, politicians, and parents, meant that this school inequality became commonplace nationally. Educational scholar Jeannie Oakes describes this process of providing already advantaged students with more advantages as a process of “multiplying inequalities” that facilitates and rationalizes “the inter-generational transfer of social, educational, and political status and [constrains] social and economic mobility.”76 Northeast High’s enrollment criteria made this transfer of privilege explicit. The school board limited enrollment in the new high school to students from this suburban Northeast area, and two-thirds of the first fifteen hundred students at the school transferred from Olney High School, Lincoln High School, and Frankford High School, which were also between 97 percent and 99 percent white.77 Among students from the old Northeast High (Edison High School), only those whose grandfathers were alumni of the school could transfer. This policy left the working-class black and white students at Edison High School to be taught by inexperienced and substitute teachers. While the new Northeast High School was built in a sprawling campus style that resembled suburban schools being built in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Edison students were left with the aging building formerly occupied by Northeast High.78

FIGURES 12 AND 13. Before and after pictures depict the loss of the school’s trophies and history. The prior class’s yearbook described the trophy case as “the symbol of the greatness of our school.” June 1957. Philadelphia School District Archives.

Neither Northeast’s alumni nor the school board ever explicitly mentioned school segregation as the motivation for building the new Northeast High School. William Loesch, an alumnus of the school and banker who sat on the school board, had lobbied school administrators to consider building a new Northeast High since Central High School received a new building in 1939.79 The alumni association advanced this campaign in 1954 when it met with Add Anderson, the school board’s business manager, who controlled the budget for new school construction. In approving the plans for a new Northeast High, Anderson cited the need for a high school to serve the growing population in the “Greater Northeast” section of the city.80 Commenting on school construction in 1962, school superintendent Allen Wetter also argued that “population” and “cost” were the main considerations, and that “the segregation issue was no factor at all in the making of … recommendations for new schools.”81 In letters and phone calls with Floyd Logan, moreover, both Anderson and Wetter continued to insist that the school’s building policy was color-blind and that school segregation was a housing-related development beyond the school’s control.82 The case of Northeast High belies these claims. By choosing to build a new high school in the suburban section of the city, the school board created a school that enrolled 99 percent white students through the mid-1960s. The drastically dissimilar racial demographics at Northeast High and Edison High were indicative of the growing segregation in Philadelphia’s public high schools in these years. By 1961, while the total high school population was 34 percent black, four schools were over 90 percent black, and seven schools were over 90 percent white.83 Despite the race-neutral rhetoric, the school board’s construction decisions built and maintained de facto segregated schools like Northeast High.

In building the new Northeast High, the school board not only exacerbated school segregation; it also left students at Edison High with a limited range of course offerings. Whereas the school once offered a full range of academic, commercial, and trade courses, the students at Edison were channeled into lower-level vocational courses like paper hanging, painting, simple woodwork, and upholstery.84 These limited curricular options were commonplace at majority-black high schools in the city, where school officials used IQ tests to determine the appropriate tracks for students. One such school, Franklin High, provides an important counterpoint to the experience of the new Northeast High.

After five years of pressure from Logan, the school board started construction on a new Franklin High School in 1955. Although construction on Northeast High and Franklin started in the same year and both new buildings cost $6 million, the types of education offered within these buildings differed dramatically. While the students at Northeast High took college preparatory courses and commercial courses that would prepare them for employment, most students at Franklin were offered the same watered-down vocational options as students at Edison. Logan tried to address these inadequacies before the board released architectural plans for the new building.85 As the new high school building neared completion in September 1959, Logan, along with the Reverend William Ischie and the Reverend Leon Sullivan, pastor of Zion Baptist Church in North Philadelphia, met with school board members to demand that students at this new building not receive the same unequal education offered to students for years at Franklin.86 Wetter again dismissed Logan’s demands, arguing that Franklin was not districted on a racial basis and that it was the policy of the schools to gear course instruction to the capacity of the students, as determined by IQ tests.87 Using this policy, the school board rated Franklin High as a “minus” school because the average student IQ score was twenty points below the city average. The plus and minus ratings were unpublished, but in his research Logan learned that the school board listed most all-black and majority-black schools in the minus category.88 These IQ-based ratings dictated that the curriculum available to students at Franklin High would be different from that at Northeast High. Across the school system, this curriculum differentiation most often meant that administrators tracked black students into courses that limited their prospects for future employment and higher education.89

TABLE 3 PERCENTAGE OF BLACK STUDENTS IN PHILADELPHIA HIGH SCHOOLS BY DISTRICT, 1956–1965

SOURCE: Philadelphia Board of Education, Division of Research, “A Ten-Year Summary of the Distribution of Negro Pupils in the Philadelphia Public Schools, 1957–1966,” December 23, 1966, FL collection, Acc 469, box 2.3, folder 6, TUUA; “Number of Negro Teachers and Percentage of Negro Students in Philadelphia Senior High Schools, 1956–1957 [n.d.],” FL collection, Acc 469, box 14, folder 10,TUUA.

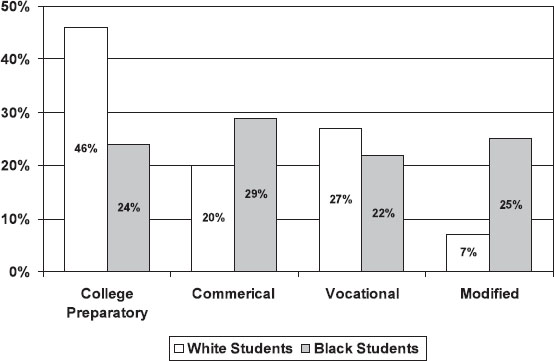

CHART 1

SOURCE: William Odell, “Educational Survey Report for the Philadelphia Board of Public Education,” February 1965, Philadelphia School District Archives.

Aware of the dangers of racialized tracking, Logan continued to press Wetter regarding the academic reorganization of Franklin. “In approving the expenditures of more than $6,000,000 for creation of the new Benjamin Franklin High School,” Logan wrote, “it is evident that the Board of Public Education had in mind an improved type of high school, not only in building and facilities, but in curriculum, student body, and so forth. … Otherwise, if the status quo is maintained, the expenditure of such a large sum of money will not be justified.”90 Logan’s concern was prescient. Months before the school board officially dedicated the new building in May 1961, the first class of students to attend classes in the new building prepared for graduation. Only 21 of the 151 students (14 percent) who started three years earlier graduated.91 Echoing the growing literature on the low educational achievement of “culturally deprived” minority children in urban schools, the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin placed the blame for this low graduation rate on the school’s student body. The Bulletin’s editorial argued that Franklin’s students came from “‘migrant families’ … newly arrived from the Deep South,” that many grew up in “homes in which there never has been a recognized father or husband,” and that in Franklin’s “sanitary halls, under the authority of its educated and gentlemanly faculty, some students experienced their only real contact with civilization.”92 Logan criticized the Bulletin’s attempts to blame Franklin’s students in a letter to Wetter and several newspapers. In the letter, Logan also reminded Wetter of his promise to reorganize and expand the curriculum at Franklin to include programs in mathematics, science, and foreign language, and to publicize these changes to the community in a brochure.93 In the fall of 1961, as a result of Logan’s years of work and a citywide increase in academic guidance programs at mostly black high schools, the board introduced new curriculum options at Franklin, and graduation rates at the school increased slowly through the early 1960s.

The limited educational opportunities available to black and working-class students at Edison and Franklin were not anomalies, but rather were in line with the school board’s curriculum tracking policies. Although the school board publicly stated that IQ tests, not race, were the criteria for this tracking, race often came to stand in as evidence of the limited potential of students in majority-black schools. In a letter describing Edison High to a member of an outside evaluation committee, for example, Wetter wrote: “because the population of the school is about half Negro there are many slow learning pupils.”94 Whether through test scores or assumptions about performance made by teachers and counselors, administrators disproportionately tracked black students into lower-level programs. Drawing on her two decades of research, Jeannie Oakes shows that tracking labels, once affixed to students, are difficult to overcome and shape how teachers view students, as well as how students view their peers and themselves. “Because public schools are governmental agencies,” Oakes argues, “tracking is a governmental action that classifies and separates students and thereby determines the amount, the quality, and even the value of the government service (education) that students receive.”95 The school board’s decision to build schools in parts of the city where they were guaranteed to be one-group schools, such as Northeast and Franklin, was a double injury for black students because racially isolated schools maintained de facto segregation and naturalized curriculum tracking on the basis of race.

Logan’s fight to equalize curricular options in mostly black schools ran up against the national push for high schools to group young people based on standardized test scores and to focus attention on the highest scoring teenagers. James Conant’s nationally published reports on education, The American High School Today (1959) and Slums and Suburbs (1961), were at the forefront of this push for more testing and tracking.96 While Conant was a prolific writer and speaker on educational issues during and after his tenure as president of Harvard University from 1933 to 1953, The American High School Today and Slums and Suburbs reached a broad popular audience. Funded by the Carnegie Corporation and published by McGraw-Hill, the reports were treated as news stories rather than academic reports. To this end, a meticulously planned media campaign accompanied Conant’s work and garnered favorable stories in Life, Look, Newsweek, Time, and U.S. News and World Report.97 In these nationally published reports, Conant endorsed more extensive standardized testing that would enable counselors to precisely identify students’ abilities and guide them to appropriate courses of study. Through this method, he suggested, the comprehensive high school could remain true to its meritocratic mission by fine-tuning the process of curriculum differentiation. While he emphasized the benefits of curriculum differentiation for students at all ability levels, the majority of Conant’s recommendations focused on improving the quality of education offered to “gifted” students.

Conant’s reports had influence because they were timely and pragmatic. His first report was published in the wake of the launch of the Soviet Sputnik space satellite in October 1957. Concerned that the United States was losing the cold war because of a failing school system, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) in 1958. The NDEA allocated millions of dollars to improve science, math, and foreign language training and to better educate gifted students. In this context, Conant’s recommendations to expand ability grouping, increase the number of counselors, and emphasize the training of gifted students largely overlapped with the educational practices already in place at high schools across the country.98 In addition to endorsing the existing practices of guidance and grouping, Conant also avoided the controversial subject of integration in The American High School Today. When he addressed the issue in Slums and Suburbs, he argued that improving vocational programs should take precedence over integration: “Antithetical to our free society as I believe de jure segregation to be, I think it would be far better for those who are agitating for the deliberate mixing of children to accept de facto segregated schools as a consequence of a present housing situation and to work for the improvement of slum schools.”99 As was the case with Conant’s other educational recommendations, many school officials embraced his position on segregation because it required little immediate action. In Philadelphia, the educational status quo Conant endorsed meant that teenagers would continue to attend high schools that were both highly segregated and rigidly differentiated in terms of curricular options and access to college.

The post-Sputnik emphasis on testing and tracking dovetailed with the national discourse of cultural deprivation. From the late 1950s through the end of the 1960s, educators and social scientists published books and articles and held conferences and seminars on the topic of cultural deprivation. They sought to examine, explain, and remedy the lagging academic skills of low-income students and students of color in urban schools. While cultural deprivation research influenced policy makers and professional educators and reached a wide popular audience, the term acquired its strength from its vagueness. Some commentators, like Conant, used cultural deprivation as a synonym for slum, and called for larger and better staffs and more money for schools in these areas.100 Other researchers used the term to describe what they called the “cultural differences” between racial and socioeconomic groups.

The Research Conference on Education and Cultural Deprivation, held at the University of Chicago in June 1964, for example, gathered over thirty leading social scientists and received financial support from the U.S. Office of Education. The authors of the conference report noted that they used the term “culturally disadvantaged or culturally deprived because we believe the roots of their problem may in large part be traced to their experiences in homes which do not transmit the cultural patterns necessary for the types of learning characteristic of the schools and the larger society.”101 While the report’s recommendations laid the groundwork for school breakfast and lunch programs and Head Start preschool education for low-income children, the authors offered few specific ideas regarding curricular guidelines, materials, or methods to improve academic performance. Moreover, the report’s emphasis on the deficits of low-income students omitted any discussion of the students’ talents or recommendations for structural changes to schools.102

As the conference report influenced federal educational policies, Frank Riessman’s The Culturally Deprived Child (1962) was being widely used in teacher preparation programs and was reaching a broad popular audience. Riessman, a professor of education and psychology at New York University, contended that the number of culturally deprived children in the nation’s largest cities had increased from one in ten in 1950 to one in three in 1960. “Effective education of the ‘one in three’ who is deprived,” he argued, “requires a basic, positive understanding of his traditions and attitudes.”103 Riessman critiqued educators for seeking to make low-income students into “replicas of middle-class children” and encouraged teachers to develop an “empathetic understanding” of “culturally deprived” students.104 Yet, as Riessman sought to refocus the approach of schools to educating low-income students, he also implied that “lower-class culture” and “middle-class culture” were clearly defined and delineated ways of life.105

While these cultural deprivation researchers differed in their recommendations, their cultural approach to educational performance allowed other commentators to use students’ backgrounds as a deterministic explanation for academic failure. The Philadelphia school board, for example, picked up cultural deprivation theories in its curricular recommendations. Emphasizing that “everyone is different,” a 1962 Philadelphia public school report outlined curriculum plans for three groups of students: a college preparatory course for the “academically talented,” commercial and vocational curricula for “student[s] who will enter the world of work” after graduation, and a modified course for “slower learning” or “culturally deprived” students.106 Philadelphia’s schools, therefore, remained devoted to tracking in the early 1960s and continued to disproportionately track black students away from the academic programs and into the modified curriculum.

Despite this racialized tracking and the increased number of segregated schools, the school board continued to be proactive in its insistence that it did not discriminate against black students or support segregated schools. A 1960 report prepared by Wetter, “For Every Child: The Story of Integration in the Philadelphia Public Schools,” made this point emphatically. While Logan and other civil rights advocates began discussing potential legal action to force the board to address de facto segregation, Wetter praised the board’s early adoption of intercultural education materials as evidence of progress on integration. “As early as 1943,” Wetter recounted, “the Superintendent of Schools led the way for the development of a comprehensive program in human relations.”107 Here again, the school board manipulated the Fellowship Commission’s intercultural education efforts to deflect criticism and delay action on school segregation. Wetter also contended that “what has been called by certain groups ‘de facto segregation’ in some schools has not been the result of policy of The Board of Public Education,” but that “the record of progress of the Philadelphia Public Schools in the integration movement is among the best, if not the best, of those of the great cities of the Nation.” The Philadelphia school board refused to back down from the de facto rationale that school segregation was the result of private housing decisions for which the board had no power or responsibility.

In the 1950s, civil rights advocates who fought educational discrimination in Philadelphia’s public schools met far more defeats than victories. The work of Maurice Fagan, Floyd Logan, and the numerous activists and parents who challenged prejudice and inequality in schools is instructive for what it reveals about the challenges of fighting de facto school segregation. Black Philadelphians and their allies faced a de facto dilemma that has emerged as the fundamental barrier to integrated and equal education in the half-century since Brown. Everyone could see that schools were becoming more racially segregated, and there was substantial evidence that these racially separate schools were not equal. Yet foes of de facto segregation, in Philadelphia and elsewhere, lacked legal redress.

Logan and Fagan challenged discrimination on a student-by-student and school-by-school basis, while also looking beyond the neighborhood level to change school board policies. Their tactics helped to secure new school buildings, introduce intercultural educational materials in the curriculum, and, to a limited extent, expand curriculum programs at majority-black schools. Their efforts were overwhelmed, however, by discriminatory housing policies that produced residential segregation and the school board’s refusal to admit that its school construction, zoning, and transfer policies contributed to segregation, or that it should take any affirmative steps to address this segregation. While these educational advocates struggled to change school policy, as the next chapter shows, they also waged a media battle to convince their fellow Philadelphians that the city operated a segregated school system that needed to be restructured.