The only thing we did wrong was to let segregation stay so long.

—Protestors at Philadelphia NAACP picketing a school construction site, May 1963

In her introduction to Freedom North, historian Jeanne Theoharis contends that in “history textbooks, college classrooms, films, and popular celebration, African American protest movements in the North appear as ancillary and subsequent to the ‘real’ movement in the South.”1 Such histories, Thomas Sugrue suggests, “are as much the product of forgetting as of remembering.”2 Thanks to work by Theoharis, Sugrue, Komozi Woodard, Martha Biondi, Matthew Countryman, and many other historians, the story of civil rights in the North is no longer a footnote. Calling attention to northern civil rights struggles was also a cause for concern for Philadelphia activists in the 1950s and 1960s. National news coverage, as well as Philadelphia newspapers and television stations, paid far more attention to school segregation in the South than to similar stories in northern cities. This media coverage laid the groundwork for the historical amnesia regarding northern civil rights. At the same time, however, Philadelphia’s civil rights activists tried to use the media to make de facto segregation an issue that the school board could not avoid. Black educational activist Floyd Logan, for example, found the widest audience for the issue of Philadelphia’s school segregation in the wake of the integration crisis at Little Rock’s Central High School in the fall of 1957.

The coverage of the Little Rock crisis in Philadelphia’s print and broadcast media raised the profile of the city’s own educational issues to a higher level than in the previous two decades. Logan took advantage of this opportunity to secure the school board’s first statement on non-discrimination and to foreground school segregation as an issue to be taken up by the city’s civil rights advocates. Three years before Little Rock, Logan tried to raise awareness of de facto segregation following the first Brown decision in May 1954. Logan sent telegrams to city and state school officials requesting immediate compliance with the decision. In his message to the city school board, Logan argued that “the time is opportune for the Philadelphia School district to redistrict in such a manner as to effect integration of its 10 all-colored schools and its many predominantly colored schools.” Similarly, Logan called Pennsylvania governor John Fine’s attention to the existence of segregated schools in Philadelphia and other parts of the state and asked him to ensure that Pennsylvania would “conform to the momentous decision of the United States Supreme Court.”3 Logan’s attempts to link the Brown decision with segregation in Philadelphia went unnoticed in the mainstream press. Unlike the month of front-page coverage Little Rock received in Philadelphia’s newspapers, the Brown decision was quickly summarized in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and the Philadelphia Inquirer as a southern case.

Without an ongoing story line, these mainstream papers covered the Brown decision for only two days. Only the Philadelphia Tribune, the city’s leading black newspaper, continued to discuss school segregation in Philadelphia and Logan’s work to eradicate it. In addition to his lobbying of politicians and school officials, his advocacy for black students and parents, and his research on the schools’ practices and policies, Logan essentially functioned as the Tribune’s education reporter in these years. Logan played a central role in the network that circulated news of civil rights issues. His collection of information on the Philadelphia schools and his persistent requests for action by school officials enabled the Tribune to make the city’s school segregation a recurring topic at a time it received little attention in the white press.4 Logan also worked as an amateur archivist, keeping detailed records of his correspondence with school officials (records that provide the foundation for this and the previous chapter). Using the visibility of Little Rock as leverage, Logan helped the school segregation issue in Philadelphia reach a larger audience in the black community and set the stage for larger protests in the early 1960s.

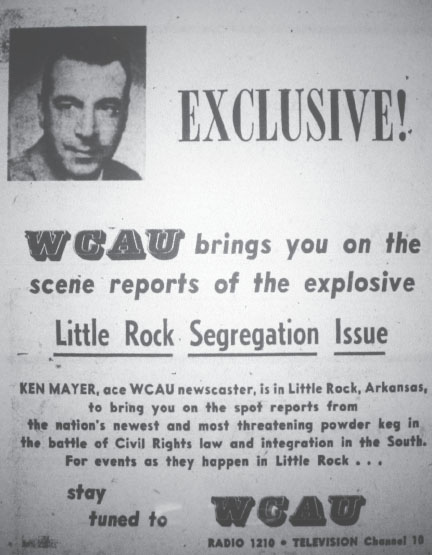

While the Brown decisions came and went quietly from Philadelphia newspapers and broadcast media, the struggle over integration in Little Rock was on the front page of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and the Philadelphia Inquirer for over twenty-five days in September and October 1957.5 School segregation conflicts in Virginia, Tennessee, and Texas also became front-page stories.6 In addition to print media, Philadelphia’s CBS affiliate, WCAU-TV, sent reporter Ken Mayer to Little Rock to track what WCAU-TV called “the nation’s newest and most threatening powder keg.”7 The Little Rock crisis also received nightly coverage on national television news, and was followed by a large national audience of viewers that journalist Daniel Schorr described as “a national evening séance.”8 As historian Taylor Branch has argued, “[t]he prolonged duration and military drama of the siege made Little Rock the first on-site news extravaganza of the modern television era.”9 Television news established its legitimacy in the late 1950s in large part by covering civil rights stories like Little Rock. Unlike American Bandstand and other entertainment programs that pursued a national audience by avoiding controversy, television news relied on the visuality and topicality of certain racial incidents to establish its authority to frame national issues for a national audience.10

At the same time, media coverage of Little Rock and other cases of “massive resistance” in the South presented racism and school segregation as a uniquely southern problem. Launched in 1956 by U.S. senator Harry Byrd of Virginia, massive resistance described a group of student placement and school funding laws designed to maintain southern school segregation in defiance of federal court orders. Although not all southern whites supported these policies, massive resistance gained broad and vocal support among diehard segregationists and many southern politicians. The pro-segregationist views underlying massive resistance were put into action by white mobs who harassed and threatened black students who sought to attend formerly all-white schools across the South, including in cities such as Charlotte, Nashville, and, most famously, Little Rock.11 Racial violence in small southern towns also made its way into American living rooms. As legal scholar Peter Irons notes, “most white Americans learned about mob violence in town like Cilton (TN), Man-field (TX) and Sturgis (KY) from television news reports.”12 For most of the 1950s and early 1960s, these arch-segregationist politicians, white mobs, and public confrontations were absent from the northern fight over school integration, and the less visible causes of de facto school segregation did not receive the same level of media scrutiny. This media invisibility made school segregation in northern cities like Philadelphia much more difficult to fight.

FIGURE 14. WCAU-TV advertised “on the scene” reports from Little Rock with newscaster Ken Mayer. September 11, 1957. Philadelphia Evening Bulletin.

Nevertheless, local events linked Little Rock to Philadelphia. Just days after Arkansas governor Orval Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to stop nine black students from enrolling at previously all-white Central High School, rumors of a shooting in South Philadelphia sparked racial tensions among teenagers. The Philadelphia police commissioner attributed these tensions in part to Little Rock, and the Philadelphia Inquirer criticized the perception that racial tensions were exclusively a southern story.13 The events at Little Rock’s Central High School also motivated black teenagers in Philadelphia to challenge the discriminatory admissions policies at American Bandstand, whose broadcast studio was located in West Philadelphia.14

FIGURE 15. The Philadelphia Inquirer noted the connection between Little Rock and racial tensions among teenagers in South Philadelphia. October 2, 1957. Hugh Hutton/Philadelphia Inquirer.

The long shadow of Little Rock helped open the door, albeit slightly, for public discussions of local school segregation issues in Philadelphia. While national media coverage of Little Rock portrayed the “Little Rock Nine” in sympathetic terms vis-à-vis the white mob they encountered outside the school, the local mainstream media attention given to Philadelphia’s de facto school segregation was more ambivalent. On one hand, the Philadelphia story was less clear than Little Rock, and, at least until the early 1960s, it lacked the characters and images of the southern story. On the other, southern civil rights stories were safe for Philadelphia media in ways that local issues were not. Reading and watching stories about Little Rock required Philadelphians to form opinions, but did not necessarily require them to take action in their own city. In contrast, raising the specter of integration in Philadelphia forced citizens to consider changes to their schools, and mainstream newspapers and televisions stations were keenly aware that their audiences did not universally support civil rights activism in the city.

Still, Logan believed that building public awareness of de facto segregation was an essential step in forcing the school board to take action. In Philadelphia, as in cities from New York to Los Angeles, Little Rock influenced newspapers outside the South to examine race issues in their own cities.15 Little Rock prompted the Philadelphia Inquirer, for example, to run the first school segregation story in the Philadelphia mainstream press, a joint interview with school superintendent Wetter and Charles Shorter, executive secretary of the Philadelphia branch of the NAACP. In his first public comments on the question of school segregation, Wetter argued that Philadelphia’s school board was doing its best to address integration. “I sincerely believe that our record of carrying on a full program of integration in Philadelphia is as fine as that found in any city across the America,” Wetter told the Inquirer.16 To rebut this claim, Shorter raised several of the issues to which Logan had called attention in the previous years, including school construction policies and student transfer policies. Wetter conceded: “We haven’t gone as far as we’d like to. … But I think that we’re on the right track.”

Although it was far from a promise to take action to address de facto segregation, Logan mailed the article to state officials, writing that “the interview establish[es] beyond reasonable doubt, the racial patterns as they exist with respect to pupils and teachers in our local school system.”17 As the Philadelphia Tribune ran frequent stories on the struggle over school segregation in the South, Logan pressed the Philadelphia school issue over the next year through repeated appeals to Wetter and state educational officials.18 Logan asked these officials to address boundary lines, student transfers, and teacher assignments. Logan escalated his appeals in February 1959 when he organized a group of black educational activists, including representatives from the Philadelphia NAACP, the Philadelphia Tribune, and several African American churches, who presented the school board with a petition outlining demands to implement nondiscriminatory policies. In a brief supporting this petition, Logan wrote: “For 26 years the Educational Equality League has been striving for interracial integration of Philadelphia public schools. In the beginning, we, too, favored the gradual approach. But today we are certain that we have advanced far beyond the gradual stage.”19 Despite his exasperation with the delays of the board, Logan was still forced to wait while the board considered his petition. Finally, on July 8, 1959, the school board unanimously adopted an official policy barring racial discrimination in the city’s public schools. The resolution, drafted by Philadelphia Tribune publisher E. Washington Rhodes, the only black member of the school board, outlined a color-blind policy, but did not address the affirmative steps requested by Logan:

WHEREAS the Board of Public Education seeks to provide the best education possible for all children; and

WHEREAS the Educational Equality League and other organizations have requested the adoption of written policies for full interracial integration of pupils and teachers:

Be it resolved, That the official policy of The Board of Public Education, School District of Philadelphia, continues to be that there shall be no discrimination because of race, color, religion, or national origin in the placement, instruction and guidance of pupils; the employment, assignment, training and promotion of personnel; the provision and maintenance of physical facilities, supplies and equipment; the development and implementation of the curriculum including the activities program; and in all other matters relating to the administration and supervision of the public schools and all policies related thereto; and,

Be it further resolved, That notice of this resolution be given all personnel.20

While Logan described the press coverage generated by the policy as one of his “major accomplishments,” the school board’s policy did not spell out specific actions with regard to school boundaries, school construction, or student assignments to promote integration.21 By stating that nondiscrimination “continued to be” the policy, moreover, the board sought to absolve itself of having ever supported discriminatory policies.22 Complicating the issue for Logan and his colleagues was that by 1960 even the board’s limited rhetorical commitments to antidiscrimination policies and programs raised concerns among white Philadelphians that civil rights groups exercised undue influence in the schools.

The Fellowship Commission was the first to feel the backlash against civil rights advocates working in the schools. As it built its relationship with the schools throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Fellowship Commission did not call public attention to its school efforts. The hostile reception the group received when working on housing issues, especially among working-class and middle-class white communities that feared the influx of black families into their neighborhoods, convinced Fagan and his colleagues of the difficulty of persuading people to hear the Fellowship Commission’s antidiscrimination message.23 A 1956 update on its educational seminars, for example, noted the importance of not “push[ing] the reluctant too hard and too early.” The report also noted that the Fellowship Commission responded to early fears that the group “might want to barge into classrooms” or “meddle in school affairs,” by foregoing its typical publicity campaign.24 The increased media and community attention to education in the wake of Little Rock, therefore, made the Fellowship Commission’s intercultural education ideas and language more important to the school system’s public presentations, while it also jeopardized the Fellowship Commission’s actual work in the schools.

This disjuncture between the school system’s public embrace of antidiscrimination language and actual classroom practices came to the forefront when the schools considered adding intercultural education materials to the high school curriculum in 1960. The textbook controversy that followed effectively ended the Fellowship Commission’s work in the public schools. In February 1960, following a wave of anti-Semitic vandalism in the Philadelphia area, Fagan met with David Horowitz, associate superintendent in charge of community relations.25 Fagan requested that a survey of textbooks be conducted to probe their treatment of the Nazi era in Germany, as well as issues of civil rights, housing, religious freedom, immigration, hate movements, and intergroup relations. Fagan suggested that the school board hire a sociologist to conduct the survey, but instead Horowitz conducted the initial review, which he submitted to the Fellowship Commission along with copies of the textbooks in question and a copy of the board’s new guide to the American History and Government course.26 This new course of study, prepared after the Fellowship Commission’s survey request, included a unit on the maintenance of good intercultural relations. As topics to investigate in the intercultural relations section, the guide listed “persecution of minority groups in Hitler’s Germany; Immigration laws affecting people of Asian origin and the McCarran-Walter Immigration Act; the Fair Employment Practices Commission; and Jim Crow racial restrictions and efforts to end segregation in the schools.”27 While this course guide marked the first time intercultural education was included in the official school curriculum, as opposed to in seminars or supplementary pamphlets, the guide noted that the time allotted to the units “should be determined by the need of the individual school.”28

After reviewing these materials, Fagan wrote to Horowitz to praise the intercultural relations unit as “excellent” and to thank him for the school’s prompt review of the textbooks. While Fagan was pleased that none of the textbooks contained “derogatory or prejudiced references,” he criticized the textbooks for omitting historical facts related to the Nazi era, for the absence of nonwhite people in illustrations, and for the “bland” treatment of civil rights. Fagan recommended that the school system advise textbook publishers of these shortcomings and request improvements.29 On July 5, 1960, Fagan presented these recommendations at a press conference that included Horowitz, Helen Bailey of the school’s curriculum committee, and two other school representatives. The two sides differed on what the schools could ask of the publishers. Fagan thought that the schools shared responsibility for advising publishers when textbooks needed improvement, while Horowitz thought this was beyond the function of the school system. The meeting, nevertheless, ended cordially. The school representatives agreed to hold an annual meeting every fall with the social studies department heads and a group of concerned citizens led by the Fellowship Commission. The Fellowship Commission also agreed to write to the National Education Association and national intergroup agencies requesting that similar textbook studies be conducted in other cities, with the hope that publishers would be more likely to respond if several cities pressed for textbook changes.30

While this meeting was not noticeably different from the moderate demands the Fellowship Commission made of the schools in the past, the textbook survey sparked a controversy regarding the authority of the Fellowship Commission to advise the public schools. On July 6, the day after the meeting, the Bulletin announced that the school board planned to add a unit on intercultural relations to the high school’s social studies classes in the fall.31 While the Fellowship Commission’s textbook survey in February 1960 influenced the school’s decision to develop these units in the following month, the Bulletin article gave the impression that the school board drafted the unit as an immediate response to the prior day’s meeting. The newspaper exploited this confusion in an editorial on July 10, 1960, titled “Indoctrination Course.” “Within 24 hours,” the editorial charged:

the educators announced that next fall … pupils will be instructed on Jim Crowism, on efforts to end school segregation, on slums and housing, on the importance of city planning. How they will be instructed will be the fascinating thing to see. In accordance with the strong beliefs of the Fellowship Commission? In accordance with the equally strong and often quite different beliefs of the taxpaying parents whose schools these are?32

Superintendent Wetter responded with a letter published in the following Sunday’s paper. Wetter wrote to assure readers that “no new courses were developed in 24 hours to meet deficiencies cited in the Commission’s report,” and that the materials in intercultural relations and urban renewal had been in preparation for several months.33

Wetter’s letter, however, ran below a second Bulletin editorial that criticized him for “knuckling under” to the wishes of the Fellowship Commission. The editors pointed out what they viewed as a conflict between the beliefs of the Fellowship Commission and those of other city residents:

Moderation, even in instructing against bigotry, is the point of the matter. The Fellowship is sincere and well within its rights in espousing a rapid end to what it believes to be evil—housing segregation, for example. Yet, many a kindly citizen would be astonished to find that by the Fellowship’s indices he would be ruled a bigot. The public schools belong to all Philadelphians. Many of these owners of the schools would deem it wrong if they were used as told to speed social progress under an extreme definition thereof.34

The readers’ letters that the Bulletin choose to publish as “evidence that moderation is the wise course” point to a mounting segregationist backlash to the Fellowship Commission and its moderate civil rights work. One reader wondered by “what authority [the Fellowship Commission] have become judges of school textbooks,” and argued that “the taxpaying public is sick to death of narrow-minded bigots … seeking undeserved privileges.” Another reader, calling the Fellowship Commission “propaganda artists,” noted that “they’ll have fewer and fewer children to deal with as the free-thinking opposition continues removing to the suburbs in search of more independent schools.”35 Portraying themselves as taxpayers willing to move to the suburbs to avoid the encroachment of civil rights “propaganda artists,” these letter writers used the rhetoric of private property rights similar to the white homeowners’ groups that fought against neighborhood integration.36 This language also anticipated the antibusing activists who described “neighborhood schools” being unfairly threatened by “forced busing.”37 In the case of the textbook controversy, making sections on the Holocaust and Jim Crow optional parts of the school curriculum prompted charges of indoctrination from the city’s largest newspaper and many of its readers.

In his reply to these editorials, Fagan said that the Fellowship Commission had no problem with the editors recommending moderation, noting that the Fellowship Commission had been charged with being too moderate for its position on fair housing legislation. “Our criticism … is not leveled at moderation,” Fagan offered, “but rather at those who are so frightened by the label ‘controversial’ that they not only avoid but oppose efforts to explore all sides of such controversies.” Fagan concluded by asking, “Is it really too much to call for social studies textbooks to deal forthrightly and fairly with the pros and cons of the issues affecting the security, rights, liberties, opportunities, relationships and responsibilities of all racial, religious, and ethnic groups?”38

Despite the controversy caused by the Bulletin editorials, the new units on intercultural education and urban renewal entered the curriculum in the fall of 1960. Through 1961, Fagan corresponded with Horowitz regarding errors and misstatements in the textbooks and met with the heads of the social studies departments to discuss additional intercultural resources for these units. The textbook controversy, however, ended the close relationship between the Fellowship Commission and the school system. Isolated from the public schools, Fagan and the Fellowship Commission turned its attention to a campaign to establish a community college in Philadelphia.39

Unlike the highly visible integration crisis in Little Rock, the school segregation crisis in Philadelphia played out in letters, policy statements, newspaper articles, and editorials rather than on school steps or television screens. Like Fagan’s often co-opted intercultural education initiatives, the heightened profile of Philadelphia’s segregation problem, which Floyd Logan had worked so long to foster, was a mixed blessing. Publicity made more people aware that school segregation was not strictly a southern issue, but left open the question of how and by whom this issue should be addressed. Logan’s position, that the school board should implement affirmative policies to promote integration, gained popularity among many civil rights advocates, but received little citywide publicity and was not enough to effect change in the school board’s policy. The school board sidestepped Logan’s demands by co-opting the Fellowship Commission’s antidiscrimination rhetoric and refusing to commit to any specific actions to address integration. Despite the school board’s caution regarding the question of integration, even these limited intercultural efforts prompted critiques of the school board by citizens who viewed intercultural education as a form of civil rights propaganda. By the early 1960s, the struggle over segregation in the city’s schools emerged from written demands and evasions into courtroom arguments and street protests.

In recognition of Logan’s fight against de facto segregation, the Philadelphia Tribune named him the paper’s Man of the Year for 1959. In the tribute to Logan, the paper contrasted his modest means with his accumulated research on educational discrimination:

Floyd Logan has little money. He receives no salary. He lives in an apartment and maintains himself from a small pension he receives from the Federal Government, after long years of service.… Yet, he has more information at his fingertips about the school system than most highly paid executives. His bulging files contain complete records of every step made to advance the cause of equality in public education.40

Although the school board refused to implement his demands, Logan provided the knowledge and experience on which later educational advocates would draw. Taking up Logan’s lead, by the early 1960s Philadelphia’s schools became an important target for a coalition of black civil rights activists. Like Logan, these activists pushed the school board to address de facto segregation at the city level, while they also lobbied against educational discrimination in individual neighborhood schools. Unlike Logan, this new wave of educational activists had the resources to bring litigation against the school system and had a larger basis of support organized among the city’s black churches, civic groups, and neighborhoods. Moreover, unlike the Fellowship Commission’s interracial coalition building or Logan’s largely solitary work, the new educational activists increasingly looked to intra-racial mass protest techniques to secure equal educational opportunities for black students. In their protests, these community members encountered a school board that continued to deny the existence of bias, as well as increasingly vocal opposition from predominantly white sections of the city.

Logan played a supporting role on educational issues throughout the 1960s, though not entirely of his choosing. The Philadelphia branch of the NAACP, which had been an inconsistent ally on educational issues through the 1950s, began to play a more significant role in fighting school segregation.41 Logan and the NAACP worked together briefly in an attempt to force state officials to establish legal requirements to act affirmatively for integration. Logan initiated a strategy to change the state law governing school enrollment boundaries and presented his argument to the Governor’s Committee on Education in 1960. “If Pennsylvania really wants interracially integrated public schools with respects to pupils, and teachers,” Logan argued,

it must amend Section 1310 of the School Laws of the State by specifically regulating the wide discretionary powers of pupil assignments, including transfers [that] will not result in perpetuation of present racially segregated schools, and the creation of other all and predominantly [sic] white or Negro schools. … Also, a flexible system of districting for pupil enrollment should be devised in which representatives of the general community should be given a voice.42

Following this meeting, the Governor’s Committee on Education recommended that the state pass a “fair educational practices law … banning discrimination on account of race, color, or creed” and that it conduct a study of the school boundary lines and student transfer policies throughout the state.43 The state officials also scheduled an initial meeting with Wetter, Logan, and representatives from the Philadelphia NAACP for April 1961.

After years of the Philadelphia NAACP’s sporadic activity on the local educational front, Charles Beckett, the branch’s recently appointed education committee chairman, met with Logan several times in 1960 and 1961. As Beckett reported to his colleagues, “Years of proficient research, investigation and forthright presentation made to official bodies have provided [Floyd Logan] with a storehouse of knowledge and information invaluable to the community and state within which and for which [he] has labored so effectively.”44 The NAACP, however, was also preparing to file a lawsuit against the schools and canceled a scheduled meeting with state and local school officials because the organization felt it “would serve no purpose.”45 Logan considered the cancellation “shocking” and reminded school officials and the NAACP of his work on school issues. “In the first place, it was the Educational Equality League which made the original request for a state investigation,” Logan argued. “Hence, we do not feel that such a feeling on the part of the NAACP, justifies the cancellation of the scheduled meeting.”46 Cecil B. Moore, a lawyer and community activist who had lost the previous two elections for NAACP branch president, supported Logan’s stance:

We are anxious to have the investigation proceed as expeditiously as possible by methods which will effectively implement desegregation without regard to any position taken by the NAACP. … [W]e should proceed now as several years may elapse between the commencement and certainly successful termination of imminent litigation, whereas the practices of which we complain may continue during those years, with their attendant harmful effects on the education of a large majority of Negro pupils.47

The cancellation of the meeting delayed the start of the state’s study of school boundaries, but, more important, it created a rift between Logan and the NAACP’s leadership that limited the effectiveness of both parties.

In June 1961, the Philadelphia branch of the NAACP filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, charging the Philadelphia Board of Education with discriminating against black students and teachers by not providing and maintaining a racially integrated school system. The NAACP brought the case, Chisholm v. Board of Public Education, on behalf of black students at Emlen elementary school in the northwest section of the city. Parents and community members in this area had raised questions for the previous five years regarding the boundary lines and student transfers that made Emlen almost all-black while the neighboring Day school was almost all-white. The case was among the first northern school desegregation cases and came just months after Taylor v. Board of Education (1961), in which a federal judge found gerrymandering of school district lines in New Rochelle, New York, to be unconstitutional. The New Rochelle case did not rule on de facto segregation, but it prompted a flurry of legal activity against school districts in the North, Midwest, and West before the Supreme Court’s decision in Keyes v. School District No. 1 (1973), which found evidence of unconstitutional segregation in Denver and expanded desegregation requirements outside the South.48 Leon Higginbotham, who led the Philadelphia NAACP’s legal team and was the branch president when the Chisholm suit was filed, recalled the difficulty of proving de facto segregation in a 1991 interview with Anne Phillips:

What was … insidious was that you had declarations by the school board saying that they opposed segregation … so that therefore you could not try what I call a “document case” in the traditional sense where you have what we call in evidence “a smoking gun.” … So what we tried to do is determine: How do you set up a case to demonstrate to a court that the way in which boundaries are chosen [is] not a matter of pure coincidence? … [T]here was enough if I thought that I had to go to trial as a trial lawyer that I would be able to establish and to discover questions of policy which [went] back a half-century almost, at which time there’s just no doubt that there was discrimination in the system. And, therefore, the whole argument in the northern cases would be that after you have established a prima-facie case of administrative policies, intentionally designed to preclude integration of students, that is the equivalent of [de jure segregation].49

The challenges Higginbotham and his colleagues encountered in pursuing this case were similar to those Logan had met over the previous decades; that is, they needed to extract evidence of educational discrimination from a school board that insisted it did not discriminate. Gary Orfield has shown that foes of de facto segregation in other northern and western cities faced similar barriers to litigation. “The lower courts,” Orfield argues,

would act only when the NAACP could provide incontrovertible proof of intentional, broad discrimination by school boards. Finding such evidence about the intentions of past school board members was almost impossible. Although they may have been well aware of racial patterns and of the racial implications of their zoning, site selection, transfer policy, and other decisions, they rarely discussed them in public. A clear pattern of decisions that had intensified segregation usually emerged, but they were not the kind of thing explicitly noted in the board’s minutes.50

The Philadelphia school board, which operated largely outside of public view and assiduously avoided controversy by publishing only administrative details in its minutes, proved an especially difficult target.51

Compounding this legal challenge, by the time a judge heard the case in early 1963, the NAACP’s local leadership was in flux. Higginbotham resigned in 1962 to accept an appointment to the Federal Trade Commission in the Kennedy administration. In the election to replace Higginbotham, Cecil Moore won the NAACP branch presidency thanks to his popularity in black working-class neighborhoods and his promises to take the branch in a more militant direction. In addition to Higginbotham, who was co-counsel on the case, all but one of the twenty-four lawyers working on the case pro bono left because of the controversy and political alliances within the branch.52 Due to the lingering tension over the canceled meeting, moreover, the original legal team did not take full advantage of Logan’s research materials and lacked the funds to conduct new surveys of school boundary, student transfer, and teacher placement policies. One of the outgoing members of the legal team, William Lee Akers, wrote to Moore regarding the challenges this case presented. “I do not believe that any lawyer who has a day to day practice or employment can do justice to the case,” he wrote. “I would be pleased to continue to assist in this case but am firmly resolved that I will not go to the poorhouse by attempting to carry this monster on my own shoulders. … This is most unfortunate and is not what the case and the Association deserve, but I have no choice.”53 By spring 1963, Isaiah Crippens was the only attorney remaining on the case. Without a team to conduct the necessary research, Crippens agreed to wait until two committees on school segregation appointed by the school board filed their reports.54

If the NAACP’s traditional legal approach to educational discrimination was threatened by branch politics and a lack of funds, it was also increasingly out of step with the mass protest strategies favored by black leaders and community members frustrated by the persistent inequality in the city’s schools. Cecil Moore, the newly elected NAACP branch president, became the most prominent of these local protest leaders. As historian Matthew Countryman describes, Moore positioned himself “as a local version of Malcolm X, the only black leader in the city unwilling to censor his words and actions to conform to white liberal sensibilities.”55 Moore helped build this reputation by organizing a picket at a junior high school construction site in the predominantly black Strawberry Mansion section of North Philadelphia. The protest was a continuation of more than a month of protests over labor discrimination at city-sponsored construction projects, and started just days after Moore and the Philadelphia NAACP organized a rally at City Hall to support the civil rights demonstrators who were attacked in Birmingham, Alabama.56

The pickets at Strawberry Mansion Junior High linked employment discrimination in school construction with the issues of school segregation and school-sponsored apprenticeship programs that discriminated against blacks. Like the schools’ site selections for Northeast High School and Franklin High School, the Strawberry Mansion site ensured that the school would be segregated as soon as it opened. That the skilled union workers building the school were almost exclusively white was largely a result of the exclusion of black students from apprenticeship classes. These classes used public school space and resources to train future union workers. The unions selected the students who could participate in the classes, and first preference was usually given to sons and nephews of union members. In other cases, ethnic associations and neighborhood churches and clubs provided apprentices for larger unions. In almost all cases, the family and social networks that fed these apprenticeship programs excluded blacks from the building trades.57 To protest these conditions, the NAACP began picketing the school site on May 24. Small groups of protesters arrived at the construction site every morning, and they were joined each afternoon by teenagers and blue-collar workers who came from their schools and work sites, respectively. As they walked around the entrance to the construction site, protestors shouted, “The only thing we did wrong was to let segregation stay so long.”58 Taking up the theme of this protest chant, the Philadelphia Tribune’s editorial page noted that although a state law prohibiting discrimination in school construction was passed fourteen years earlier, “There was no effort made by anyone to enforce it, despite the fact that it is generally agreed that there has been and continued to be discrimination against Negro skilled labor.”59 Among the hundreds of picketers were black laborers assigned to work on the school site who refused to cross the picket line. “This is a false democracy when qualified colored people can’t get a job building schools for their own kids,” one worker told the Tribune.60 This combination of employment discrimination against adults and educational discrimination against young people motivated protestors to stay on the picket line for a week.

After the fifth and most violent day of clashes between protestors and police, the school board and construction leaders agreed to the NAACP’s demand that five black skilled workers be hired at the site and that a joint monitoring committee be appointed to increase black employment in skilled trades. In negotiations prompted by the protests, the school board also agreed to close apprenticeship programs that excluded black students. At the time, the Strawberry Mansion pickets were the largest mass protest against educational discrimination in the city’s history. Although they did not force the school board to take action to address school segregation, the protests provided black leaders with another strategy to use against the school board’s delays. “The old procedures of quiet protest have been abandoned for open demonstration,” the Tribune declared in an editorial on the importance of education to civil rights.61 The threat of protests, and media coverage of these protests, became a key tool as Moore and other black activists continued to fight the school board through the summer of 1963.

In addition to these mass protests, Moore and the NAACP continued to pursue a legal victory over school segregation in the Chisholm case. Judge Harold Wood set September 15, 1963, as the date by which the schools and the NAACP would have to come to an agreement to avoid going to trial. The school’s nondiscrimination committee had prepared a plan for desegregation in advance of the deadline, but Walter Biddle Saul, a former school board president and the school board’s counsel for the Chisholm lawsuit, refused to file the document with the court. Filing a plan for desegregation, Saul argued, would constitute an admission that the school segregation existed, which he insisted was not the case.62 In response, Moore and the 400 Ministers, a group of clergy who led a successful selective patronage campaign against local companies with discriminatory hiring practices, threatened to organize direct action protests and student boycotts if the board did not adopt an acceptable policy.63

The tension between these activists and the school board increased when Judge Wood ordered the board to adopt a desegregation plan that included changes in school feeder patterns to further integration. Wood also granted a continuance in the case, meaning that it would not go to trial as long as both parties submitted a progress report every six months. The Tribune portrayed this decision as an unmitigated victory, declaring: “Parents of children across the city raised their voices in a chorus of ‘hallelujahs,’ as the Board of Education accepted unconditionally the demands of the NAACP for a desegregated school system.”64 The desegregation plan included reviews of school boundaries and school building programs and agreements that the board would modify its boundary policies and building site selection to foster desegregation. In total, the plan committed the school board to take many of the affirmative steps toward integration long encouraged by educational advocates.

Rather than overturning de facto segregation, however, the judge’s order sparked another round of delays by the school board, protests by civil rights advocates, and counterprotests by segregationist antibusing groups. In the first protest following the order, black parents joined Moore and the NAACP in pickets at Meade Elementary School in North Philadelphia after the principal announced plans to address overcrowding by busing students to another segregated school. In addition to the school protests, the NAACP led pickets at the Board of Education building, the home of the school principal, and the homes of superintendent Wetter and Robert Poindexter, one of two black members of the school board. Moore promised to keep the pickets going until students at the overcrowded school could transfer to an integrated school. “We’ve learned that you can’t believe what the Board says it’s going to do,” Moore told the Tribune.65 After a student boycott kept half the students out of classes for one day, Moore successfully negotiated the transfer with school officials.66 Building on this victory, Moore warned that the school board would face larger protests if it continued to delay desegregation efforts: “Be it in the courts, the streets, or the ballot box, the NAACP will integrate the schools. If they’re going to be stubborn, we’ll show them that what we accomplished at the Meade School and at 31st and Dauphin sts. [Strawberry Mansion Junior High construction site] was only a petty example of what they can expect in the future.”67 As the school board filed progress reports that retreated from its earlier desegregation plans, these mass protest tactics became increasingly important to civil rights advocates.

The struggle over school desegregation in Philadelphia peaked in 1964. As required by the continuance in the Chisholm case, the school board filed a progress report in January announcing plans for limited student busing. A second report in April laid out plans to realign the boundaries of half of the city’s elementary schools.68 In both cases, the plans were designed to relieve overcrowding first and secondarily to foster integration. The plans drew criticism from both civil rights advocates and antibusing groups. Isaiah Crippens, the NAACP’s attorney in the Chisholm case, dismissed the first report as a “public relations gimmick, a hoax, a linguistic swindle.”69 Many black parents also doubted the school board’s intentions and, with the assistance of Moore and the NAACP, protested boundaries and overcrowding at two schools.70

The school board’s reports also prompted parents in several predominately white neighborhoods to form groups to oppose the proposed busing and boundary changes. Speaking at meetings throughout the city, Joseph Frieri, the leader of the Parents’ and Taxpayers’ Association of Philadelphia, the largest of these antibusing groups, argued for the importance of neighborhood schools. Rather than busing or boundary changes, Frieri argued, the schools should focus on remedial training for low-income black children whom, he claimed, were culturally deprived. Members of another antibusing group dramatized Frieri’s concerns by carrying a coffin symbolizing the death of the neighborhood school into a school committee meeting.71 Mayor James Tate and City Council President Paul D’Ortona joined these parents in attacking the school board’s plan for limited busing. D’Ortona claimed that busing would increase juvenile delinquency and leave students “prey to moral offenders.” D’Ortona also toured white sections of the city delivering these arguments and urged white citizens to “storm City Hall” to defend neighborhood schools.72

In supporting segregation by sounding warnings about culturally deprived and delinquent black youth, these antibusing leaders identified black students as the problem with Philadelphia’s schools. This line of argument built on a magazine article, published earlier that year, that attacked Philadelphia public schools and black students. Published in Greater Philadelphia Magazine, a magazine marketed to members of the Philadelphia business community, “Crisis in the Classroom” claimed to be an inside report on the Philadelphia school system. Greater Philadelphia Magazine reporter Gaeton Fonzi worked for just six days as a substitute teacher and spent a month talking with administrators and teachers. Fonzi’s statement of concern for the state of education in Philadelphia’s schools fixed blame on unprepared, unruly, and violent black youth. The teachers of these students, he argued, were “living a professional lie, refusing to admit, even to themselves, that what they face daily is the impossible task of trying to reach human beings who don’t want to be reached.” In Fonzi’s view, “culturally deprived” black students were synonymous with the public schools, and were at the root of the schools’ problems. “The great bulk of the Philadelphia public school system is composed of an economically deprived, socially-suppressed class of adolescent who has been environmentally conditioned to a life that is without hope or ambition,” Fonzi wrote. He continued:

The Philadelphia public school system is, in other words, a Negro system. But it is more than that: it is a ghetto system overburdened with the intellectual, moral and economic remnant of society. The private and parochial schools have siphoned off the cream of Philadelphia’s school-age population, both Negro and white. The children who go to the public school system are those who have no where else to go.73

Fonzi went on to degrade black teachers “recruited from hole-in-the-wall type Southern Negro state colleges” and to call the Philadelphia public schools “the most obscene institutions in the city.”74 Echoing attacks on welfare that gained strength in the mid-1960s, Fonzi described the visit of a truancy officer to a poor neighborhood in order to criticize a mother of seven on public assistance and to ask “what sort of behavior can be expected from a child who doesn’t know what a father is or whose older sister is a whore?”75 In this attack, Fonzi singled out William Penn, a majority-black all-girls school in North Philadelphia, as an example of what he felt was wrong with Philadelphia’s public schools. Noting the school’s “Code of Behavior” (Do act like young ladies at all times. Don’t use profane or foul language.), he scoffed: “How ridiculous such minimum middle-class standards seem in contrast to actual behavior not only at William Penn but in most of the schools. Young ladies? Dozens drop out each year because of pregnancy.”76 Fonzi further described the success of small groups of students in counseling and motivation programs as “diamonds in a pile of manure.”77

In its coverage of the story, the Philadelphia Tribune reprinted Fonzi’s article, followed by a two-part rebuttal by Floyd Logan. Logan likened the article to those authored by “Southern racist writers” who sought to “denigrate the image of the Negro child, his mental ability, character, health, home and family background, even his birth, in order to emphasize his unassimability into predominately white schools.”78

While it is tempting to dismiss Fonzi’s article as the thoughts of an isolated bigot, his criticisms of black students came at the peak of the struggle over school segregation in Philadelphia. Against civil rights activists who pushed the school board to take affirmative steps to integrate Philadelphia’s schools, Fonzi’s racist article provided rhetorical support for antibusing protestors who contended that black students were culturally deprived and would benefit from remedial education rather than integration.79

Logan and Moore rebutted the claims of these antibusing leaders. In response to Mayor Tate’s intervention into the busing plan, Logan resigned his position on the Mayor’s Citizens Advisory Committee on Civil Rights.80 Taking a more vocal position on desegregation than he had in the 1950s, Logan told the Tribune: “All this business about asking white people if they want colored children in ‘their schools’ is nonsense. We’re talking about law, not opinion polls. The School Board must have the courage to do what is right regardless of opposition from either whites or Negroes.”81 In a speech at a NAACP meeting, Moore extended Logan’s critique to the subject of the neighborhood school: “The only difference between a segregationist like Paul D’Ortona and one like Gov. Wallace is that one uses ‘neighborhood rights’ and the other ‘states rights’ to disguise his basic desire to keep the Negro enslaved.”82 Moore’s statements highlighted the concept of neighborhood schools as one of the most powerful ideas available to officials and citizens who opposed desegregation efforts. The neighborhood schools concept tapped into sentiments that led white homeowners in Philadelphia and other cities to organize groups to “defend” their neighborhoods from what they perceived to be the threat of black migration.83 The discourse of neighborhood rights also resembled the freedom of choice rhetoric used in southern school districts after civil rights advocates challenged massive resistance laws in federal court. Matthew Lassiter argues that antibusing groups in Charlotte crafted an “identity politics of suburban innocence that defined ‘freedom of choice’ and ‘neighborhood schools’ as the core elements of homeowner rights and consumer liberties.”84 By maintaining segregation in both housing and schools, these groups, in Philadelphia and elsewhere, sought to preserve localized forms of racial privilege. Like the school board’s antidiscrimination rhetoric, moreover, holding up neighborhood schools as an ideal allowed school officials, politicians, and citizens to adopt a color-blind ideology and avoid integration without publicly supporting segregation.

Respect for the neighborhood school concept also underscored the Lewis Committee’s report on school integration required by the Chisholm case. Appointed by the school board, the Lewis Committee was an interracial group of community representatives interested in integration. The report affirmed the committee’s “unanimous belief in the principal of integrated public education,” but outlined preconditions for reorganizing schools to achieve full integration that would have been difficult for even the most optimistic integration advocate to envision. The committee recommended:

First the community as a whole and especially those people living in predominantly white neighborhoods must be convinced that the very existence of the city and their own enlightened self-interest depend on their acceptance of integration as the modern and satisfactory pattern for life—in housing, in jobs, and in education. … The second fundamental need to be realized before integration of the schools on a wide basis can take place successfully is to improve the educational achievements of the schools themselves.85

The Fellowship Commission’s limited success in persuading people to embrace anti-prejudice ideals made the first requirement seem far-fetched, while the years of neglect of majority-black schools like Franklin made the second equally unrealistic. The report concluded with suggestions for integration that the schools might implement at an undetermined future date, and recommended that the busing of white children to foster integration be given “no further consideration.” Instead, the committee suggested additional compensatory and remedial education for students in underperforming schools, primarily black and Puerto Rican youth. Set in the context of protests and counterprotests over what the schools could and should do to address school segregation, the Lewis Committee’s report sided with the segregationist antibusing groups and absolved the school board of taking any affirmative steps to promote integration.

The fight over educational discrimination in Philadelphia’s schools continued after the Lewis Committee report, but the school board would not make any serious moves toward desegregation after 1964. Maurice Fagan and the Fellowship Commission celebrated the opening of the Community College of Philadelphia after a fifteen-year legislative and public relations campaign. The Community College opened doors to higher education for a large number of students.86 Floyd Logan continued to work on educational issues, focusing on the schools near his home in West Philadelphia (the new West Philadelphia High School gymnasium was named after Logan in 1979).87 Cecil Moore continued to be the most prominent and outspoken black leader in Philadelphia. On the educational front, Moore tried to reopen the Chisholm case in 1966 to get a ruling, but his request was denied. Moore also led an eight-month protest of Girard College, a boarding school for fatherless boys that excluded black youth. Although Girard College was unaffiliated with the public schools, the school’s ten-foot stone walls made it a highly visible symbol of racial exclusion in North Philadelphia. Protests at the school in the summer of 1965 provided an outlet for the anger felt by black teenagers and received extensive coverage from the Philadelphia Tribune.88

In addition to the Girard College protests, Moore played a supporting role as a younger generation of Black Power activists organized high school student protests in the summer and fall of 1967.89 A decade after Little Rock, the educational inequalities in Philadelphia’s de facto segregated schools became a very public issue. These protests prompted negotiations among students, parents, community activists, and school officials that led to a larger role for black community members in the governance of majority-black schools, including black-only student groups in the schools and black studies courses. At the same time, police commissioner Frank Rizzo capitalized on white opposition to these school protests and the school reform efforts when he was elected mayor on a strong anti-civil rights platform in 1971.90 At the start of the 1970s, Philadelphia’s schools were among the most racially segregated in the country, with 93 percent of black students attending majority-black schools and one in twenty attending all-black schools.91

On the legislative front, the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission issued an order in 1970 requiring five state public school districts to develop plans to balance the racial composition of students in their schools. The Philadelphia school board challenged the Human Relations Commission’s authority to act in the absence of de jure segregation. The case that emerged, School District of Philadelphia v. Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission (1972), was the first of eleven cases stretching over almost forty years. In the wake of U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Milliken v. Bradley (1974), which held that desegregation plans could not extend into suburban school districts unless multiple districts had deliberately engaged in segregated polices, the Pennsylvania Commonwealth Court allowed the school board to submit a voluntary plan for integration that did little to lower the number of racially identifiable schools. The Human Relations Commission conceded that with students of color making up the majority of the public school population, racially integrating the school system was not feasible. By the 1990s, the school board submitted a plan to the court that said little about racially isolated schools, focusing instead on general educational reform efforts. The school desegregation case ended in 2009 when the Commonwealth Court judge accepted the school district’s five-year strategic plan that was approved by the Human Relations Commission and the educational advocacy groups representing the defendant. The plan, Imagine 2014, outlined several goals, including the school district’s commitment to increase the compensation for teachers in low-performing schools, to allow low-performing schools to select teachers without regard to seniority, and to institute weighted student funding within five years to increase the resources available at low-performing schools.92 While unnoted in the school board’s press release, in making this plan for the future of Philadelphia schools, the school board also echoed the past. Imagine 2014 reiterated the demands for improved educational opportunities for low-income students and students of color made by Floyd Logan and his fellow educational activists over the previous six decades.

Underlying Floyd Logan’s quest to make de facto school segregation a media issue was faith that publicizing educational inequality would compel the school board to take action. In this view, the Brown decisions and Little Rock provided openings in which to make school segregation a relevant issue for all Philadelphians. As political theorist Danielle Allen has argued, images from Little Rock “forced a choice on U.S. viewers” regarding their “basic habits of interaction in public spaces” as citizens, and that many “were shamed into desiring a new order.”93 While Little Rock raised questions of citizenship for Philadelphians, the local import of this national civil rights story was far less clear. Counter to Logan’s hopes, as Philadelphia’s school segregation became more highly visible, the school board, politicians, and white parents became more adamant about protecting the status quo at the expense of integrated education and equal educational opportunities for black students. Ultimately, Logan did not overestimate the importance of media publicity so much as he underestimated the extent of entrenched white resistance to integration.

The failure of school integration in Philadelphia made other spaces of intercultural exchange among teenagers more important. Radio programs, concerts, record hops, talent shows, and television shows dedicated to rock and roll became important sites of youth culture in the 1950s. In some cases, these youth spaces allowed teens to interact with cultural productions and peer groups across racial lines. At other times, youth spaces rearticulated the ideals of racial segregation. The next chapter examines the emergence of rock and roll in Philadelphia and the deejays and teenagers who shaped the city’s youth culture.