12 What is a Lacanian clinic?

Is there a Lacanian clinic? Undoubtedly. It is based on fidelity to the Freudian psychoanalytic method, a fidelity that, paradoxically, demands innovation. If Freudian psychoanalysis is a method of research and treatment of the psyche, it continues to be so in Lacan, although transformed. The psychoanalytic clinic employs the “talking cure,” and Lacan, like no one else, revolutionized the relationship between language and psychoanalysis. Free association is still the thread running through psychoanalytic practice, enriched thanks to a subverted linguistics. Its rationality is formalized and determined by the rule of free association, a process in which chance is rigorously harnessed. This program results in a freedom from any a priori determinism, whether biological or sociological, which would undermine the very exercise of psychoanalysis. The psyche to be cured is regarded as a subject-effect caused by the interplay of signifiers in the unconscious, a process that dissolves its supposed ego-like solidity, and, in a word, de-substantializes it. Therefore, the Lacanian clinic requires a complex conceptual battery, which may be discouraging for those who expect comfortable technical recipes. If there is one thing the apprentice psychoanalyst will not find, it is a recipe. Not only because a recipe would not be appropriate to the specificity of each unconscious, but because the unconscious and the subject it generates are deeply marked by the historicity which affects the exercise of psychoanalysis in each period, and which retroactively affects the unconscious itself.

Lacan has been called a Structuralist, and this is of course partly true, but for him any structure – with a lack or hole in its center – is marked by the vicissitudes of history, precisely through the symbolic order it organizes. There is no better example than how childish babble, which Lacan termed lalangue, bears on the constitution of the subject on the one hand, and how, on the other hand, the products of science and technology affect subjectivity. Over time, the Freudian method has reached theoretical depths which give it new brilliance and increased efficacy. The parameters allowing for this conceptual and practical extension are the three orders of the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real.

Lacan rethinks transference, and he does it through an unprecedented exploration of the triad guiding his work: love, desire, and jouissance. He starts with the redefinition of the psychoanalyst’s role as one who occupies the symbolic locus of the listener, and whose “discretional” power consists in deciding the meaning of the subject’s message. He can, however, only interpret this meaning as it is produced by specific signifiers provided by the analysand’s free association. This privileged listener is one who is supposed to have some knowledge about the specific unconscious at stake; that is, as the “subject-supposed-to-know,” he or she will form the structural basis of transference. But this transference is not merely the reproduction of what has already happened; at its center is a factor ignored by Freud but already described by Melanie Klein: the partial object, the latent referent that is revealed when the analysand’s construction of the subject-supposed-to-know collapses. I will focus on one of the least developed aspects of the Lacanian clinic – its articulation of the neuroses, a theoretical endeavor that emphasized their logical dimension. In particular, I will examine the concept of the objet a (which, according to Lacan himself, was his only contribution to psychoanalysis), and the development of the formulae of sexuation. These concepts open a new dimension in our thinking about sexuality (particularly female sexuality), the position of the psychoanalyst, and the relationship between language and the unconscious.

The nucleus structuring the Lacanian clinic is the non-existence of the sexual relationship. This proposition can be rephrased in three different ways: there is no knowledge of sexuality in the unconscious; there is an unconscious because there is no complementarity in the sexes; and there is no sexual “act.” The lack, a failure proper to the structure in Lacan, consists in the absence of sexual relationship. In the face of such a lack, several supplements are produced so as to suture it. At the center of the unconscious, there is a hole, the gap of the sexual rapport, a hole which is the Lacanian name for the castration complex. There are two forms of logical non-existence, i.e. of lack, which are central to praxis, insofar as they are the corollary of the non-existent sexual relationship: the non-existence of truth as a whole and the non-existence of jouissance as a whole.

The sexual law arises where sexual instinct is lacking. This law, this interdiction, is coherent with unconscious desire, and even implies the identity of desire and law. For the speaking being, it institutes the dimension of truth in a fictional structure. Thus, psychoanalysis “socially has a consistency that is different from that of other discourses. It is a bond of two. That is why it replaces and substitutes the lack of sexual relationship.”1 This lack establishes that real point by providing an “impossible” entirely specific to psychoanalysis. An opposition between truth and the Real runs through the Lacanian clinic in a dialectic which has neither been synthesized nor surpassed. The Real is that which always returns, and it is indissociable from the logical modality of the impossible, a logic that is incompatible with representation and a correlate of the not-all, that is, of an ineluctably open set. Truth in psychoanalysis is contingent and particular, a conception that was already expressed in Stoic theories of logic.

As to the clinic, the moments when Lacan stresses the relationship between what is true and the analytic interpretation are when the subject’s historicization achieves primacy in the analytic work. When he gives priority to the real in its relationship with the psychoanalytic task, he stresses logic and structure. If interpretation is renewed by resorting to equivocation within language, this is also done, even scandalously, by modifying the orthodox length of sessions through scansion. We should remember that Freud fixed the length of a session at forty-five minutes in terms of the attention span that worked best for him, never in relationship to the temporality of the unconscious. Brief sessions became the center of a scandal, and because of the scandal, people forgot that sessions must be of variable length in response to how the analysand’s work unfolds. The duration varies according to the opening and closing of the unconscious, which uses standard time to favor resistance so as to counteract the closure which results from fixed time sessions.

Chronological time and the temporality of the unconscious are different. Doubtlessly this change increases the psychoanalyst’s responsibility, his “discretional power,” but it also disrupts routine action; it awakens him or her from comfortable naps. Although Lacan pointed out that the analysand is perfectly capable of handling a 45-minute session, nothing changes in the ultra-short session. Cutting the session short emphasizes the simultaneity of several lines in the signifiers of the analysand’s free association. Whether or not the cut is timely can only be known afterwards, après-coup, because the effect of an interpretation can only be read in its consequences. This involves a risk, which should be as calculated as possible, although this calculation is no guarantee against erring. Psychoanalysis is an atheistic practice, and the analytic act lacks an Other to guarantee it. No God, and no proper name can act as God for psychoanalysts; not even Lacan’s name guarantees the efficacy and correctness of our work.

The same can be said of the calculated vacillation of analytic neutrality, in which the psychoanalyst intervenes by intentionally stepping back from his neutrality, levying sanctions or granting approval based on signifiers and the desire of the historical Others of the analysand, not as a function of her or his personal feelings. This vacillation has always been practiced, even though never publicly admitted, and it relies on the use of counter-transference. Thus the calculated vacillation entails the psychoanalyst’s desire, a concept which corrects distortions of counter-transference, appropriately situating it as a dual imaginary reaction, which the psychoanalyst should approach as one plays the role of the dummy at a game of bridge – that is, by no longer participating in the specular game.

These kinds of interventions occur in the framework of a repetition that is not understood as a mere reproduction of the past, a concept which led to an interpretation of all free association relating to the psychoanalyst, in the “here, now, and with me” of transference, to the point of boredom. Calculated vacillation of neutrality is not a “technical” norm. It is employed because the psychoanalyst should preserve for the analysand the imaginary dimension of non-mastery, imperfection, ignorance (hopefully docta) facing each new case.

Transference love is instituted from the beginning since it is based on the structural formation of the subject-supposed-to-know, which produces a juncture between an undivided subject and unconscious knowledge. This construction makes possible the elision of the subject’s division, a division which must never be lost sight of in psychoanalysis. When the psychoanalyst assumes that structural position, he must never forget that he too is a divided subject. When the analysand agrees to submit to the free association rule, she removes all supposition of knowledge from her sayings, accepting that she does not know what she says, although she does not know that she knows. The subject-effect produced by free association – the divided subject – comes into being insofar as it abandons its ego knowledge.

For Lacan, the psychoanalyst should play the role of subject-supposed-to-know but be situated in a skeptical position, rejecting all knowledge except for that gathered from the analysand’s sayings. This is a skeptical version of Freud’s rule of a floating attention according to which the psychoanalyst listens isotonically (assigning the same value to everything that is said) and does not offer any agreement. The psychoanalyst should even “pretend” to forget that his act (agreeing to listen to the analysand’s words and accepting the cloak of the subject-supposed-to-know) causes the psychoanalytic process. This strategy leads to the position of the psychoanalyst as object, which subtends his or her position as a subject-supposed-to-know who accepts being the cause of this process.

We must now be more precise as to the function of the object a, a function which underpins the role of subject-supposed-to-know and is also the latent referent of transference. The objet a is the object which causes desire; it is “behind” desire in so far as it provokes it and should not be confused with the object that functions as target for the desire.

The first lack to which Lacan untiringly sends us is the lack of a subject. There is no given natural subject. Lacan criticizes all and every naturalistic concept of the subject. This lack sets in at the very moment when the human organism is captured by language, by the symbolic which deprives it of any possible subjective unity. But in the structure, that subject, which is not, has a locus as an object relative to the Other, whether relative to its desire or its jouissance. In other words, we are first an object. As an object, we can be a cause of desire for the Other or a condenser of jouissance, the point of recovery of jouissance for the Other. But for the human infant to find its place, whether as cause or as plus-de-jouir, a loss has to occur first. That loss operates in relation to its inscription in the Other. We are the remainder of the hole we make in the Other when we fall as objects, a remainder which cannot be assimilated by the signifier.

Thus the emerging subject tests his place in the Other by playing with disappearance; for example, he hides and waits for someone to look for him. This situation takes on dramatic overtones when this disappearance is not noticed. He seeks to create a hole in the Other, to be lacking for him. The Other, probably the mother initially, will mourn his loss. The child actively seeks to separate himself, in a separtition, as Lacan says in the Seminar on Anxiety, because when he creates a hole in the Other by turning himself into a loss, he goes out to seek something else.

Mourning after weaning is the mother’s mourning, not the baby’s. For that loss to start operating, the subject first has to discover lack, and the only place where he or she can discover it is in the Other, in other words, by finding the Other incomplete, or barred. That loss locates the subject in two ways. In one, the subject is that object taken as cause for the Other and that, in as much as it is an embodied cause linked with gut-emotions is the truth of a specific relation with the desire that determines the subject’s position. Such a part- or partial truth uncovers both the subject’s lack and the lack of the Other. On the other hand, it is a premium of jouissance which the Other recovers in the face of the absence of an absolute, whole, sexual jouissance. In this way, Lacan retrieves two main dimensions of the Freudian object: the object is first the “cause” as lost object of desire and trace of the mythical experience of satisfaction; the object is also a libidinal plus-de-jouir as in Lacan’s translation of Lustgewinn, the distinctive pleasure gain provided by primary processes, a surplus in the energy of jouissance resulting from the circulation of cathexis; this second concept underpins the political economy of jouissance in the Lacanian clinic. Lacan shows how the nucleus of the preconscious, which provides the unity of what is usually called self, is the objet a, which provides the subject with a consolation in face of the absence of the whole jouissance.

A simple example can serve as illustration. A woman in her thirties comes to see me because she is going through periods of inertia during which she stops caring for her family, her work and her personal appearance. At these times she suffers from bouts of bulimia which she refers to as comiditis or “overeating,” she eats mainly sweets, lies in bed reading romantic novels and sleeps. She has a slip of the tongue – she says “comoditis” (overcomfortable) instead of “comiditis” – which makes it possible to start formulating her basic fantasy whose axiom would be something like: “someone gives candies to a little girl.” The comfort and the passiveness, both of which appear as character traits of women in the family, relate to the desire of a paternal grandfather, a professional baker, who fed all “his women.” Passiveness, carelessness, wanting others to take care of her, are linked to being this object fed by the historical Other. In other words, she was an object allowing itself to be fed sweets. This provided her at the same time with a sweet premium of jouissance while allowing her to continue being the “cause” of the grandfather, whose role in the family had displaced her father. The analysis of her position as object relative to the desire of that Other altered her fixation to it and opened the possibility for her to decide whether she wanted what she desired.

The logical modalities of love

The objet a likewise latently organizes transference love. Psychoanalysis reveals that the main logical modality of love is contingency: psychoanalysis shows love to function as an interminable love letter underpinned by objet a as a remainder, its cause and its surplus-enjoyment. Lacanian psychoanalysis distinguishes thus two privileged, contingent forms of supplements to the sexual relationship which does not exist – the phallus and the objet a. Their conjunction produces that curious object, Plato’s agalma, the miraculous detail that plays the part of object of desire. It is the lure which unleashes transference love and presents itself as the aim of the desire, not as its cause. The formula is precise: objet a is inhabited by the lacking phallus or “minus phi” and thus sends us on the trail of the imaginary phallus of castration. The subject imagines he will come to possess that object he lacks. But unconscious desire, understood as desire of the Other’s desire, is not about possession. The Other’s desire is always reduced to desiring a, the object which is its cause. He who gets lost on the road of possessing the object is the neurotic, who does not want to know either about his own position as object causing the Other’s desire or that the Other’s desire exists because the Other is incomplete – lacking – as well.

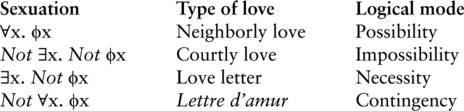

Insofar as transference love is modulated through the analysand’s demand, the latter likewise takes on different logical modalities. Each of these logical modalities develops Lacan’s sexuation formulae from Seminar XX, and provides a new insight into the subject’s sexuated position in love. From the seminars given in 1973–4 entitled Les Non-dupes errent one can deduce figure 12.1 that articulates the four logical modes of love following the sexuation formulae. Since Lacan’s tables are underpinned by a pun linking nécessité (necessity) and ne cesse de s’écrire (does not stop being written), they are hard if not impossible to translate into English. Thus I will just reproduce the essential matrix.

Figure 12.1 Matrix of the four logical modes of love

Let me say briefly something about the last two types of loves. The modality of the “love letter” imagines love as necessary, and assumes that sexual love has to replace an always possible neighborly or brotherly love. This is the mechanism by which an illusion of sexual relationship is reintroduced: a logical necessity is substituted for the absent biological need or instinct. At the other end of the spectrum, the commandment “love thy neighbor” tends to expel the body and desire from their proper places.

On the female side of sexuation, no one can say “No” to the phallic function; impossibility arises with the non-existence of Woman as Woman. Courtly love appears at this point, it is love in its proper place in relation to desire, insofar as the imaginary of the body is the medium which gathers the Symbolic of jouissance and the Real of death. There the logical mode is the impossibility of sexual relationships. On the side of the feminine universal, the not-whole-woman, we find Woman who sustains herself as a sexual value by the modality of the love letter, since it is a mode through which love reveals its truth. The last modality is that of radical contingency and takes the form of what Lacan has called lettre d’amur (instead of lettre d’amour). There love reveals its truth, namely that for the speaking being sexual union is subject to chance encounters. In Lacan’s special writing, amur – a neologism in French – is homophonically close to amour, love, but implies the privative particle a-, while suggesting the wall, mur, which sends us back to the wall of castration. Although love in its contingency does not reinforce that wall of castration, it accepts the gap opened by the absence of sexual relationship in the unconscious. Since mur is also homophonous with mûre (mature or ripe), a mur ironically calls up the impossibility of mature love. However, love’s movement aims at establishing it as necessary, thus hiding the bodily contingency of the objet a which underlies and triggers the encounter. Perhaps an adequate English version would be “love ladder,” if perchance such a wall could be scaled. This entire movement from necessity to contingency and back is sketched in Encore: “The displacement of the negation from the ‘stops not being written’ to the ‘doesn’t stop being written,’ in other words, from contingency to necessity – there lies the point of suspension to which all love is attached” (S XX, p. 145).

This trajectory resembles the progression that often appears at the end of an analysis, when the subject-supposed-to-know evaporates in loops and spirals. On the analysand’s side, this marks the destitution of the subject; then, however, love for unconscious knowledge persists, without being sutured by a subject. The objet a also emerges in its incommensurability and radical contingency, which differentiates it from an object of exchange and its common measure, and marks the inassimilable remainder of the subjective constitution. Such remainder can be called désêtre or “lack in being” since it is no more than a false being whose emptiness is revealed on the psychoanalyst’s side. The psychoanalyst then, far from being a listener endowed with discretionary powers, becomes the mere semblance of the objet a.

The unconscious structured as a language, that is to say, as lalangue, falls outside language as a universal, and its science, linguistics, is replaced by linguisterie (pseudo-linguistics) in conjunction with a clinic of the not-whole, of particularity, a clinic governed by a modal logic and a nodal topology. We need to underline that if the analysand’s sayings adhere to a modal logic, analytic interpretation must in turn adhere to an apophantic logic, following Aristotle’s notion (apophanisis means revelation in Greek), a logic of affirmation and assertion. Interpretation stands in relation to the saying of non-existence (of the sexual relationship, of the truth in its entirety and of the jouissance in its entirety). The apophantic saying places a limit, and is thus sense and goes against meaning. It will never place itself on the side of universal quantifiers because it is always a particular saying.

An example can illustrate how interpretation finds its bearings in this logical dimension. The patient was a womanizer, what we call a Don Juan, whose life was constantly beset by the many affairs he carried on. Throughout his analysis he would tell me: “You know doctor, all women want the same thing.” When I asked: “What?” he would reply: “Oh, you know . . .” This would be repeated often until one day he fell in love with a woman. He told me he had doubts about her, and had concluded that this woman must be like all the others. I repeated my question, and finally he replied: “Well, you know, they are all whores.” I replied immediately: “Thank you for the compliment,” in a highly ironic tone calculated as a vacillation of neutrality, for I was neither angry nor offended. In fact, I had implied: “Thank you, I am also included in the all women, I am no exception.” On this intervention, I interrupted the session. The important point had been that I had abandoned the position of exception in which the analysand had placed me. I was in the same position as the other exception, the master, his mother in the first place – the only woman to whom he was faithful – and in the second place his wife as a mother surrogate. By simply including myself in the series “all women are whores,” I opened the closed set of the universal Woman, by refusing to take the place of the exception that would assure that the ensemble of Woman was a closed universal set. Here, what was signified was not the central issue. This interpretation produced an intense reaction in the analysand. It opened for him a space that was not limited exclusively by his mother’s desire and stopped his compulsive womanizing.

When we are on the side of the not-whole linked with femininity, the unconscious remains an open structure; on the phallic side, the unconscious is a closed set. Signifiers, insofar as they are an open set, are not organized as a chain which implies a linear series. Instead, we are dealing with an articulation governed by the logic of proximity. This approach to unconscious knowledge is not contradictory with how it works as a closed set. Two ways of focusing on truth in its relationship with the unconscious are thus sketched out. Both are always half-truths. In relation to the closed set, truth involves the existence of a limit that makes it a half-saying. In the open set, we only find particular truths, one by one. The psychoanalyst, as though he were a Don Juan, is to take on each unconscious, one by one, because he knows there is no “unconscious as a whole,” that the universal proposition will be denied to him. Every psychoanalyst will have to make a list, one by one, of the several unconsciouses he has had to analyze. Deciphering unconscious knowledge thus has two dimensions: the half-saying or midire of the closed set and the true saying of the maximum particularity of the open set.

The ethics appropriate to this set, both closed and open at the same time, which is the unconscious, is an ethics of “saying well” (bien dire). To be faithful to it involves being a dupe of the unconscious knowledge precisely because “non-dupes err” (Lacan’s pun on noms du père – the names of the father – and les non-dupes errent, the non-dupes err). We are to be docile dupes of that unconscious knowledge because the Well Said we are dealing with is not that of literary creation, even though a rhetoric, which varies depending on the lalangue, is inherent in it. We are dealing with that Well Said which responds to the unconscious knowledge of each analysand. This is the deep reason why there is no psychoanalytic technique.

Neurosis and sexuation formulae

The sexual relationship which does not exist torments us, works on us, and ultimately leads us to psychoanalysis. Due to this impossibility which makes a hole in unconscious knowledge, psychoanalysis provides us with “truth cases,” points out how real lives are tormented by this Real. The neurotic shows a truth which, since it is not said, is suffered and endured. This is his or her letter of introduction. Suffering is to be considered an event insofar as it covers for and is the effect of a saying, an enunciation. This suffering can be a symptom but also an objet a as cause. Then we can start working.

When the neurotic seeks knowledge, this search is on an ethical level, and, according to Lacan, he is the one who traces out new paths in the relationship between psychoanalysis and ethics. The search for the père-vers (Lacan’s pun on “perverse” and “vers le père” – that is, “toward the father”) is a search for jouissance. The neurotic questions himself about how to manage the impasses of the law. He knows, in his way, that everything related to jouissance unfolds around the truth of knowledge. The horizon of his search is absolute jouissance. Nevertheless, the central issue for him is that his truth is always on the side of desire, not of jouissance, precisely because he situates himself as a divided subject ([W1]). He situates himself relative to that which he believes in, those hidden truths which he represents in his own flesh. For him, as for the pervert, that which is foreclosed is absolute jouissance, not the Name-of-the-father.

When auto-eroticism is discovered, the subject’s link to the desire of the Other (mainly the mother as Other) is often questioned, which risks unleashing a neurosis. This questioning puts the drama of the significance of the Other at stake, insofar as the latter has had a hole made in it by the objet a. Where the Other has had a hole made in it, the a will f all. The phallic signifier ([W2]) places itself in this same hole. That hole indicates the point where the Other is emptied of jouissance.

Each neurosis has its own way of coming to terms with this point of castration in the Other which indicates the non-existence of jouissance as whole or absolute. The two main neuroses – obsessional neurosis and hysteria – can be located on both sides of the sexuation formulae, insofar as the particular on each side shows us a different form of providing a basis for the primordial law.

On the side of the exception is the mythical father of Totem and Taboo – the figure Freud placed at the center of obsessive neurosis, who denies the phallic function and enjoys women “as a whole” – that is, all women. The mythical father is greedy for jouissance and drives his sons to a rebellion which culminates in his murder and totemic devouring. This ends with the communion of the brothers, each of whom can now take a woman, and the establishment of a mythical social contract, based on the interdiction of the “whole” of women. Let us underline that what is forbidden is the “whole” of women, and not the mother. In this case, jouissance as “whole” comes first, and is later forbidden by the contract among the brothers. The law which halts the absolute jouissance of the mythical father appears second. This law is an accomplice of the writing of love letters, which on the universal level is the basis for neighborly love or a sense of religious community.

On the side of the “there is not one” of the female particular, we find the Oedipal law, with the interdiction of the desire of the mother, which Freud discovered in his hysterical patients. The Oedipal law establishes a genealogy of desire in which the mother is declared to be forbidden. The subject is guilty without knowing it, because the law is there first and refers to the desire of the mother, not to jouissance. In The Reverse of Psychoanalysis we read: “The role of the mother is the desire of the mother . . . This is not something one can stand like that, indifferently. It always causes disaster. A big crocodile in whose mouth you are – this is the mother. One never knows whether she will suddenly decide to snap her trap shut.”2 The risk is to be devoured by that mother-crocodile, a risk from which the subject defends himself with the phallus. Lacan holds that Jocasta knew something about what happened at the crossroads where Oedipus kills Laius, and that Freud did not question her desire, which led to the self-absorption of the son/phallus that Oedipus was for her. Here we have first of all the forbidden desire of/for the mother, and secondly, their transgression. Observe that what is forbidden manifestly is the desire for the mother, but that behind this, the desire of the mother herself comes to the fore, to which the son’s desire for her responds. Here the law points out the object of desire and at the same time forbids it. This law is a correlate of courtly love, the impossible, and shows an appropriate positioning of desire.

Let us start with obsessive neurosis and its desire that shows up as an impossible desire to possess the “whole” of women. The obsessive neurotic, faced with the impasses of the law, aspires to a knowledge which would allow him to become the master, a knowledge in which he is interested because of its relationship to jouissance. He also knows that faced with a loss of jouissance, the only available recovery of jouissance is provided by the objet a. That loss constitutes the center around which debt, which plays a crucial function for him, is structured. Jouissance must be authorized when it is based on a payment forever renewed: the obsessional neurotic is, therefore, untiringly committed to production, to unceasing activity. Different forms of debt are included in his rituals, in which he finds jouissance through displacement. The master is the exception for him, that Other prior to castration, to being emptied of jouissance, to the law after the murder of the father. He thinks about death to avoid jouissance and sustains the master with his own body, which acts as a cadaver, obeying, we might say, Ignatius Loyola’s motto of perinde ad cadaver, to obey until the end as a cadaver. In the face of the exception which denies castration, his answer is to not exist, which gives rise to that peculiar feeling, which makes him feel always as though he were outside of himself, that he is never where he is. He thus sustains that exception which is the mythical father, that master whose cadaverized slave he becomes.

On the other hand, the hysterical patient both represses and promotes that point towards the infinite which is an absolute jouissance impossible to obtain. Since it is impossible to obtain, she refuses any other jouissance; none would suffice by comparison with that impossible jouissance. She supposes that Woman – the Woman that Lacan would call the “other” woman – has the knowledge of how to make a man enjoy, an impossible place she yearns to reach. In the face of this impasse, she sustains her desire as unsatisfied; if absolute jouissance is unreachable, everything she is offered is “not that.” This situation drives her to question the master so that he will produce some knowledge, that knowledge Woman would have if she existed. This is why any weakness of the father is so important for her, like his illness or his death. She hurries to sustain him, it does not matter how, because she does not want to know anything of an impotence which would make absolute jouissance even more unreachable.

Her tragedy is that she loves truth as the non-existence of jouissance as a whole. If loving is to give what you do not have, she unfolds the charitable theater of hysteria in this respect, her own version of love thy neighbor, a counterpoint of everything for the other of the obsessive oblation. In this charitable theater she stages the sacrifice, not the debt, where she offers herself as guarantor of the castration, even unto her own life. In the face of the non-existence of Woman, she chooses to faire l’homme like the hysteric (to play the part of a man, but also “make” a man) with all the ambiguity of this formula, which can be understood either as her assuming the man’s role or that she constitutes the man, although not any man, that man who would know what “the” woman, should she exist, would know. She identifies with the man relative to the woman. Therefore she pretends to have that semblance which the phallus is so as to relate to that “at least one man” who has knowledge about “the” woman. That woman as a whole who does not exist, impossible to register logically in the unconscious, is the basis of the unsatisfied desire of the hysterical patient.

What then is a woman? It is she who can see the light in psychoanalysis, who is open to a dual jouissance as not contradictory, who can place herself on both sides of the sexuation formulae. On the side of “not as a whole,” a jouissance opens for her under the sign of mysticism; on the other side, there is phallic jouissance. That “one woman” registers on the male side as “one” woman, but not always the same one. Thus in this structure we have recorded the matrix of a misunderstanding between the sexes. Such a logical grid shows that neuroses are the truth of a failure, the failure of the structure of the signifier relative to the inscription of the sexual relationship.

How can we think of the relationship between structure and history in this clinic? For Lacan, a child’s biography is always secondary in psychoanalysis, because it is told afterwards. How is this biography, this family novel, organized? It depends on how unconscious desire has appeared for the father and the mother. Therefore we not only need to explore history, but also how each of the following terms was effectively present for each subject: knowledge, jouissance, desire, and the objet a. Thus, the child’s biography can be thought of as the way in which the structure became a living drama for each subject. The key to how that structure became drama is the desire of the Other in its articulation with jouissance. The central point is the link between absolute jouissance as lost and the desire of the barred Other. This link comes together in the objet a, the cause of desire and plus-de-jouir. The subject must place herself as the cause of desire that she was for the other, and decide whether she wants what she desires – whether she wants to be the cause of that desire. Likewise, the subject must abandon the fixation on the plus-de-jouir that supplements the loss of jouissance that also inhabits the Other, thus opening up the space for other ways to recover jouissance. Our contingent biographies, which become necessary a posteriori, provide the possibility of a choice, and psychoanalysis takes us to this threshold. Lacan’s clinic does not engage in absolute determinism, since it foregrounds the central role of contingency, which allows the analysand the small margin of freedom that makes psychoanalysis neither an imposture nor a mystification. In conclusion, I would like to stress that a Lacanian clinic aims above all at “speaking well” (bien dire). It should make a virtue of modesty without forgetting the psychoanalyst’s own desire, with all the weight of the added responsibility this entails.