4 Lacan’s science of the subject: between linguistics and topology

Many students of the arts and humanities probably first encounter the name of Jacques Lacan in one of the numerous studies of the French Structuralist movement, an intellectual paradigm which attained the zenith of its public success during the 1960s, and which has since occupied many an Anglo-American scholar’s critical spotlight, either as a fashionable esoteric creed or as an original explanatory doctrine. Invariably associated with the contributions of Claude Lévi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, and Louis Althusser – the central quadrivium of Structuralism – Lacan’s oeuvre has indeed frequently appeared as another influential instance of how Structuralist ideas managed to change the face of many research areas in the human and social sciences, in his case the field of Freudian psychoanalytic practice. Whereas his companions have been hailed or vilified for their Structuralist approaches to anthropology, literary criticism, philosophy, and politics, Lacan has entered history as the quintessential defender of the Structuralist cause in psychoanalysis, an acolyte so militant that he did not shrink from making the claim that Freud himself had always been an inveterate structuralist avant la lettre.1

The main reason for Lacan’s recognition, and his intermittent self-identification as a Structuralist is situated in his allegiance to the basic principles of Structuralist linguistics, as inaugurated by Ferdinand de Saussure in his famous Course in General Linguistics, published posthumously in 1916, and as elaborated from the late 1920s by Roman Jakobson, founding member and chief representative of the Prague Linguistic Circle.2 As Jakobson explained in his Six Lectures on Sound and Meaning, a series of epoch-making presentations at the Ecole libre des hautes études in New York during the autumn of 1942, Saussure cleared the path for an innovative conception of language, focusing more on the meaningful function of sounds than on their anatomo-physiological basis, investigating language as a socially regulated, universal human faculty rather than a culturally diverse and historically evolving collection of words, and viewing language as a complex system of relationships between a basic repertory of sounds instead of the sum total of all the elements employed for conveying a message. To substantiate his revolutionary outlook on language, Saussure brought an impressive array of new concepts to his object of study, many of which were couched in dual oppositions. In this way he distinguished between the language system (langue) and individual speech acts (parole) (CGL, pp. 17–20), between synchronic (static) and diachronic (evolutionary) linguistics (p. 81), and between syntagmatic (linear) and associative (substitutive) relationships within a given language state (pp. 122–7). Yet Saussure’s greatest claim to fame no doubt stems from his definition of the linguistic sign as a dual unit composed of a signifier (signifiant) and a signified (signifié) (pp. 65–70).

Against the realist perspective on language, according to which all words are but names corresponding to prefabricated things in the outside world, Saussure argued that within any language system the linguistic signs connect sound-images to concepts, instead of names to things. The sound-image, or signifier, coincides with the vocal production and sensory perception associated with a verbal utterance. It therefore possesses acoustic and material (physical) qualities, the phonic aspects of which could, in principle, be registered and measured. The concept, or signified, coincides with the idea in the individual’s mind, a thought-process occuring as a result of a particular sensory impression, or seeking to express itself through a verbal utterance. Unlike the signifier, the signified possesses mental and semantic (meaningful) qualities, the psychological and social aspects of which could, in principle, be referred to the individual’s family background, education, social identity and nationality.

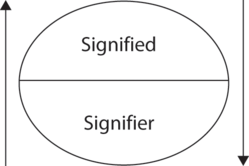

In Saussure’s linguistics the relationship between the signifier and the signified is completely arbitrary, whilst the two constitutive elements of the linguistic sign remain fully interdependent. An example may clarify this proposition. The concept (signified) of “the male individual who was born as my parents’ child before or after me” is linked in the English language to the sound-image (signifier) of “brother.” Yet nothing whatsoever within this concept predisposes it to being conveyed by this specific signifier. Proof is that the same concept is linked to very different signifiers in other languages: “frère” in French, “broer” in Dutch, “hermano” in Spanish, “bhai” in Hindi, and so on. Conversely, nothing within the signifiers “brother,” “frère,” “broer,” “hermano,” and “bhai” makes them intrinsically well-suited for conjuring up the concept of “the male individual who was born as my parents’ child before or after me.” The fact that they do is purely accidental and a matter of convention. Any other signifier could have been connected as effectively with the same signified within a certain language. In one and the same language a single signifier may even be linked with various non-overlapping concepts. In English, for instance, the signifier “brother” is not exclusively tied up with the concept of “the male individual who was born as my parents’ child before or after me.” When Roman Jakobson sent an offprint of one of his papers to Claude Lévi-Strauss with the inscription “To my brother Claude,”3 he evidently did not mean to imply that a blood-relationship of biological fraternity existed between them, but presumably wished to show his gratitude to a kindred spirit. In addition, that one amongst an infinite number of sound-images is being used for conveying a concept does not alter the arbitrariness of the relationship between signifier and signified; it merely shows that language is a fraudulent game or, to use Saussure’s designation, a “stacked deck” (CGL, p. 71). For on the one hand we are free to choose whichever signifier we want for expressing a particular signified, whereas on the other hand the choice has already been made (be)for(e) us and there is nothing we can do to change it. The language system thus sanctions specific connections between the signifier and the signified, excluding all others, which prompted Saussure to aver that the linguistic sign is a dual unity of separate yet mutually dependent elements, and to adduce the well-known schema (CGL, p. 114).

Figure 4.1 Schema showing the relationship between the signifier and the signified

From the mid 1950s, Lacan started to integrate the principal tenets of Saussurean linguistics into his own theory of psychoanalytic practice. The first article in which he discussed at length the relevance of Saussure’s ideas for psychoanalysis was published in 1957 as “The agency of the letter in the unconscious or reason since Freud” (E/S, pp. 146–78), and this was, incidentally, also Lacan’s first paper to be translated into English. Putting his trust in structural linguistics as the harbinger of a scientific revolution, Lacan posited that its entire edifice rests on a single algorithm, which he formalized as  (E/S, p. 149). Although explicitly conceding that this formula appears nowhere as such in the whole of the Course, Lacan nonetheless acknowledged Saussure as its mainspring, simultaneously promoting the Swiss scholar as the indisputable source of inspiration for modern linguistic science. In Lacan’s pseudo-Saussurean schema, S stands for signifier and s for signified, and the line between the two terms symbolizes the “barrier resisting signification” (E/S, p. 149). In response to some erroneous interpretations of the latter definition, especially that which had been advanced by Jean Laplanche and Serge Leclaire in their 1960 text on the unconscious, Lacan later pointed out that the bar between the signifier and the signified ought not be understood as the barrier between the unconscious and the preconscious, thus representing the psychic mechanism of repression, nor as a proportion or fraction indicating a ratio between two variables.4 Instead, he pointed out that the bar should be read as a “real border, that is to say for leaping, between the floating signifier and the flowing signified.”5

(E/S, p. 149). Although explicitly conceding that this formula appears nowhere as such in the whole of the Course, Lacan nonetheless acknowledged Saussure as its mainspring, simultaneously promoting the Swiss scholar as the indisputable source of inspiration for modern linguistic science. In Lacan’s pseudo-Saussurean schema, S stands for signifier and s for signified, and the line between the two terms symbolizes the “barrier resisting signification” (E/S, p. 149). In response to some erroneous interpretations of the latter definition, especially that which had been advanced by Jean Laplanche and Serge Leclaire in their 1960 text on the unconscious, Lacan later pointed out that the bar between the signifier and the signified ought not be understood as the barrier between the unconscious and the preconscious, thus representing the psychic mechanism of repression, nor as a proportion or fraction indicating a ratio between two variables.4 Instead, he pointed out that the bar should be read as a “real border, that is to say for leaping, between the floating signifier and the flowing signified.”5

Much has been written about Lacan’s distortion of Saussure’s basic schema of the relationship between the signifier and the signified. One of the earliest and most trenchant critical assessments of Lacan’s operation is included in The Title of the Letter, a meticulous deconstruction of his 1957 paper by Jean-Luc Nancy and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, which he himself praised in his 1972–73 seminar as “a model of good reading.”6 Encouraged by the vigor of Jacques Derrida’s attack on Western logocentrism in Of Grammatology and Writing and Difference, Nancy and Lacoue-Labarthe set out to demonstrate that Lacan’s linguistic turn in psychoanalysis, however far it reportedly removed itself from traditional philosophical notions, epitomized an implicit return to the age-old metaphysical concepts of subjectivity, being, and truth.7 Comparing Lacan’s algorithm of the signifier and the signified to Saussure’s original notation, the authors discerned a number of crucial differences, which prompted them to conclude that instead of taking his bearings from Saussurean linguistics, Lacan had spitefully destroyed one of the cornerstones of his alleged theoretical foundation in view of its potential appropriation for his own psychoanalytic purposes.

The most conspicuous difference between Saussure’s and Lacan’s diagrams concerns the positions of the signifier and the signified relative to the bar that separates them. Whereas in Saussure’s schema, the signified and the signifier are located above and beneath the bar respectively, in Lacan’s version their position has been interchanged. Secondly, whereas Saussure’s diagram suggests if not an equivalence, at least a parallelism between the signified and the signifier, owing to the similarity with which they are graphically inscribed above and beneath the bar, Lacan’s algorithm underscores visually the incompatibility of the two terms. For in Lacan’s formula the signifier is written with an upper-case letter (S) and the signified appears in lower-case type (s), and is italicized (s). Additionally, the ubiquitous ellipse encapsulating the signifier and the signified in Saussure’s diagrams is absent from Lacan’s rendering, and so are the two arrows that link the terms. For Saussure, both the ellipse and the arrows symbolize the unbreakable unity of the sign; the signifier does not exist without the signified, and vice versa, despite the arbitrariness of their connection. Lacan’s deletion of the ellipse and arrows thus already suggests that in his account of the relationship between the signifier and the signified the unity of the linguistic sign is seriously put into question. Finally, whereas for Saussure the line distinguishing the signifier and the signified expresses at once the profound division and the strict solidarity of the two terms, for Lacan the line constitutes a genuine barrier – an obstacle preventing the smooth crossing from one realm to the other.

These four differences between Saussure’s linguistic sign and Lacan’s algorithm of the signifier and the signified raise a number of important questions concerning the motives and corollaries of Lacan’s distortion and the general affinities between his theory of psychoanalysis and structural linguistics. Did Lacan subvert Saussure’s model because he deemed it imprecise – as indeed Jakobson had already surmised in his 1942 lecture series – from a linguistic point of view, or rather because he considered it unsuitable as a workable construct for psychoanalysis? If it was his psychoanalytic experience that inspired Lacan to revise Saussure’s schema, which aspects of this experience urged him to implement the revision in this particular fashion? And what are the consequences of Lacan’s subversion for the way in which language is held to function both outside and within psychoanalytic treatment? More generally, what are its implications for Lacan’s perceived allegiance to the Structuralist paradigm? Does it invalidate Lacan’s role as one of the key players within the Structuralist movement, or does it open the door to a more radical, super-Structuralist approach?

The first thing to note when assessing Lacan’s motives for modifying Saussure’s schema of the linguistic sign is that instead of discovering the Swiss linguist’s lectures all by himself, he was exposed to them indirectly, through the structural anthropology of Claude Lévi-Strauss. The latter’s knowledge of Saussure and structural linguistics had in turn been mediated by somebody else’s comments, notably those of Roman Jakobson, whose New York course Lévi-Strauss attended in the autumn of 1942.8 As the anthropologist admitted on numerous occasions, it was Jakobson who had provided him with a solid theoretical framework for interpreting his observations and who had encouraged him to engage in the project of The Elementary Structures of Kinship, the book which announced the birth of structural anthropology.9 Thus, Lacan initially read Saussure through the eyes of Lévi-Strauss, whose own reading had passed through the critical filter of Roman Jakobson.

In his Six Lectures on Sound and Meaning, Jakobson was generally appreciative of Saussure’s work, commending it as one of the most significant steps for the study of language sounds in their functional aspects, yet he also believed that the Course remained deeply entrenched in a “naive psychologism,” similar to many nineteenth-century treatises on linguistics.10 In Jakobson’s reading, Saussure had failed to draw the radical conclusions from his novel conception of language, emphasizing psychic impressions over the strictly linguistic functional value of sounds, and re-introducing psychic and motor aspects of sound articulation rather than advancing the formal characteristics of a phonological system. Following this criticism, Jakobson did not adjust Saussure’s concepts, but decided to elaborate on his own structural approach to language in keeping with the theses formulated by the Prague Linguistic Circle during the late 1920s.

When Lévi-Strauss dipped into Saussurean theory in The Elementary Structures of Kinship, and more markedly in his extraordinary Introduction to the Work of Marcel Mauss, his was already much more a critical re-interpretation of Saussure’s ideas than an accurate presentation of their impact. For example, Lévi-Strauss declared in the latter text that structural linguistics has “familiarised us with the idea that the fundamental phenomena of mental life . . . are located on the plane of unconscious thinking,” adding that the “unconscious would thus be the mediating term between self and others.”11 Inasmuch as Saussure and Jakobson were interested in the unconscious at all, to the best of my knowledge they had never formulated anything as specific and decisive about its importance within mental functioning. And whereas Lévi-Strauss’s first statement may still leave some doubt as to the exact nature of his viewpoint – “unconscious” could be a mere quality of certain thoughts – the second statement makes it crystal-clear that he conceived of the unconscious as a mental system, akin to how Freud had defined it in his so-called “first topography” of the unconscious, the pre-conscious, and consciousness. Further in the same section of the Introduction to the Work of Marcel Mauss, Lévi-Strauss argued that social life and language share the same autonomous reality, whereby symbols function in such a way that the symbolized object is much less important (and real) than the symbolic element that conveys it. This observation emboldened him to posit, challenging the basic principle underlying the Saussurean linguistic sign, that “the signifier precedes and determines the signified.”12 Needless to say, this proposed primacy of the signifier could still be conceivable alongside a Saussurean-type interdependence of the signifier and the signified. But Lévi-Strauss dismantled the unity of the linguistic sign as swiftly as the other components of Saussure’s theory. Substituting “inadequation” for equivalence and “non-fit” for adequacy, he claimed that no signifier ever “fits” a signified perfectly, human beings doing their utmost to distribute the available signifiers across the board of signifieds without ever creating a perfect match.13

In light of Lévi-Strauss’s singular espousal of structural linguistics, Lacan’s alleged distortion of the Saussurean sign becomes evidently more considerate and less idiosyncratic, less erratic and more deliberate. In defending the “primordial position of the signifier” and defining the line separating the signifier and the signified as a “barrier resisting signification” (E/S, p. 149), Lacan simply reiterated and formalized the ideas that Lévi-Strauss had already professed some seven years earlier. Although he did not mention his friend-anthropologist by name in his seminal 1957 article on the value of Saussure’s theory for psychoanalysis, Lacan attributed to the Swiss linguist what was in reality a Lévi-Straussian conception of the relationship between the signifier and the signified. And until the end of his intellectual career, Lacan did not budge an inch on the supremacy of the signifier and the “inadequation” of its relationship with the signified, the two hallmarks of Lévi-Strauss’s take on structural linguistics. Even when these axioms came under serious attack, towards the end of the 1960s, from Derrida’s deconstructionist critique of the Western metaphysical tradition, Lacan remained adamant that the letter (writing) cannot overthrow the signifier (speech) as the primary force of language, and that the greatest achievement of structural linguistics consists in the imposition of a barrier between the signifier and the signified.14

Lacan’s formalization of the constitutive linguistic algorithm, along the lines suggested by Lévi-Strauss, was not just indicative of his eagerness to rescue the ailing body of psychoanalysis through an injection of the latest scientific developments. His integration of clinical psychoanalysis and structural linguistics à la Lévi-Strauss was not merely inspired by a desire to accelerate the aggiornamento of Freud’s legacy. For Lacan was equally keen to underscore that Freud himself had anticipated the premises of Saussure’s doctrine and those of the Prague Linguistic Circle, so that instead of infusing psychoanalysis with a foreign substance he could safely argue that structural linguistics entailed the most advanced continuation of Freudian psychoanalysis. In the 1971 text “Lituraterre” Lacan even went so far as to recognize the signifier in the notion of Wahrnehmungszeichen, literally “perception sign,” which Freud had introduced in a letter to his friend Wilhelm Fliess of 6 December 1896.15 Remarkably, when trying to find evidence for the presence of Saussure’s concepts in Freud’s writings, Lacan never took advantage of the terminology suffusing Freud’s 1891 book On Aphasia, in which the founder of psychoanalysis had decomposed “word-representations” into four distinct images, dubbing the most important one Klangbild, that is to say “sound image,” or precisely what Saussure would later elect to designate as the signifier.16

Over and above the question as to whether it makes sense to claim that Freud had foreshadowed the principal propositions of structural linguistics, it may seem self-evident to many a reader for Lacan to attempt a revaluation of psychoanalysis through the systematic accounting of language and its functions. After all, Anna O., one of the most famous patients in the history of psychoanalysis, could not have described the treatment regime to which she had been subjected by Josef Breuer more accurately than that of a “talking cure” (SE 2, p. 30). And when Freud decided to leave the so-called hypno-cathartic method behind, in order to access more fully the pathogenic vicissitudes of representations and their effects in the unconscious mind of his patients, language became even more the privileged playground of psychoanalytic treatment. Trying to substantiate a clinical practice which relies exclusively on the effects of a verbal exchange through the promotion of linguistics may thus appear to be an act of common sense rather than a revolutionary undertaking.

However, Lacan’s main rationale for merging psychoanalysis with structural linguistics lies elsewhere. Throughout his career, he ventured to explain how Freud had demonstrated in The Interpretation of Dreams, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, and Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious that the modus operandi of the unconscious and its formations (dreams, slips of the tongue, jokes) cannot be understood without taking account of the role of the signifier and the structure of language. For instance, in his notorious 1953 “Rome discourse,” Lacan explicated at length how Freud’s tactics of interpretation ought to be conceived as a practice of reading, deciphering, and translation (E/S, pp. 57–61). In Lacan’s understanding, Freud had recourse to these procedures because the formations of the unconscious are themselves the outcome of an intense rhetorical labor – as opposed to, say, the simple transformation of words into images or the transmission of psychic energy to the biological substratum of the body. Freud’s extensive probing of word-connections in the analysis of his own forgetting of the name Signorelli thus proved to Lacan that psychoanalytic interpretation is tantamount to a reading process, and that this method is invaluable, owing to the linguistic nature of the unconscious (SE 3, p. 287).

Lacan’s discovery of a linguistic breeding-ground in Freud’s psychoanalytic theory and practice equipped him with a powerful argument against the ego-psychological tradition in contemporary psychoanalysis, whose representatives were more concerned with rebuilding their analysands’ personalities as well-adapted, competent citizens than with the dissection of unconscious formations, and in whose clinical field language functioned more as an obstacle than a necessary means. Yet, similar to his distortion of Saussure’s concept of the linguistic sign, Lacan found additional support for his personal rendering of the Freudian unconscious in the work of Lévi-Strauss. Indeed, as early as 1949, in an influential paper on “The effectiveness of symbols” the anthropologist had already proclaimed that the unconscious is synonymous with the symbolic function, which operates in every human being according to the same laws, regardless of individual idioms and regional dialects.17 Combining this insight with his own re-reading of Freud’s books on dreams, slips, and jokes, Lacan subsequently adduced the formula which would gain prominence as the single most important emblem for his entire work: “The unconscious is structured as a language.”18 The only reservation he ever made pertaining to the value of this statement concerns the tautological nature of its wording. As such, he indicated to an international audience of scholars gathered in Baltimore during the autumn of 1966 that the qualification “as a language” is entirely redundant because it means exactly the same as “structured.”19

Armed on the one hand with the idea that the signifier prevails over the signified and on the other with the formula that the unconscious is structured (as a language), Lacan devoted all his energy during the 1950s and 60s to the careful deployment of a version of Freudian psychoanalysis which simultaneously vindicated its loyalty to the founder’s original inspiration and justified its enlightened character through the principles of structural linguistics. For many of his fellow-analysts, Lacan’s interpretation of Freud was exactly the opposite of what he himself wanted it to be: they saw it as a potentially dangerous and fundamentally flawed aberration which needed to be exposed and exterminated, rather than a strictly orthodox elaboration which ought to be regarded as the only true account of the original texts. Who is the honest defender of the Freudian cause and who is the impostor? Lacan or ego-psychology? These are the issues that have divided the international psychoanalytic landscape since Lacan’s occupation of the intellectual scene as a contested, yet hugely influential maître-à-penser.

Looking back at these questions twenty years after Lacan’s death, and in a contemporary climate of newly erupting conflicts between Lacanians and the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA), it would be ridiculous to maintain that Lacan merely sought to regurgitate the naked truth of Freud’s doctrine. As he openly declared in “The Freudian Thing” (1955), the meaning of his so-called “return to Freud” was no more and no less than “a return to the meaning of Freud,” but this admission did not preclude this meaning being refracted by the prism of Structuralism advocated in Lévi-Strauss’s new paradigm of anthropological research (E/S, p. 117). In Lacan’s amalgamation of structural linguistics and psychoanalysis, both disciplines were simultaneously preserved and modified, according to the Hegelian principle of sublation (Aufhebung). If Lacan’s espousal of Saussure’s linguistic sign encompassed a fruitful distortion of its underlying tenets, then his interpretation of Freud’s work also entailed a radicalization of its main thrust. If Lacan’s psychoanalytic course supported his modification of Saussurean linguistics, however influential Lévi-Strauss’s ideas may have been, his linguistic interest also inflamed his recuperation of Freudian psychoanalysis as a clinical practice based on the power of speech and the structure of language.

After his excommunication from the IPA in November 1963, Lacan engaged in an even more vehement campaign for the recognition of his approach, solidifying its foundations and exploring its significance for the epistemological differentiation between psychoanalysis, religion, and science. Concerning the latter debate, he suggested in “Science and Truth” that the structural approach constitutes a necessary and sufficient condition for guaranteeing the scientificity of psychoanalysis, thus scorning those psychoanalysts who try to redress the legitimacy of their discipline by tailoring its logic to the requirements of empirical science, and ultimately refusing to relinquish the notion that psychoanalysis is an unscientific, speculative “depth-psychology” concerning the illogical, irrational and ineffable aspects of the mind.20 Invigorated, once again, by Lévi-Strauss’s take on the nature of a scientific praxis as detailed, for instance, in The Savage Mind, Lacan argued that the psychoanalytic delineation of the mental invariants governing the empirical diversity of the formations of the unconscious suffices to define psychoanalysis as a scientific enterprise – not a science in the traditional (positivistic, experimentalist) sense of the term, but a science nonetheless.21 Hence, the Structuralist project also offered Lacan the opportunity to realize Freud’s ardent wish to see psychoanalysis included among the sciences.22

The aforementioned differences between Saussure’s formula of the linguistic sign and Lacan’s algorithm of structural linguistics indicate how Lacanian psychoanalysis no longer puts the signifier and the signified on an equal footing (considering its reliance on the primacy of the signifier), and how it repudiates the possibility of a self-contained, unitary relationship between a sound-image and a concept (considering its emphasis on the barrier between the two components). In a sense these two key characteristics of Lacanian theory sustain each other, because the imposition of a cut between the signifier and the signified increases the autonomy of the signifier, and the latter’s separation from the signified is directly proportional to its symbolic autonomy.

The direct implication of these two characteristics for clinical psychoanalysis is that it ought to concentrate on the existing relationships within the network of signifiers rather than on the relationship between a signifier and a signified outside its sphere of influence. Lacan believed that analysts ought to target their interpretations at the connections between the signifiers in their analysands’ associations, and not at the meaningful links between signifiers and signifieds (S IX, p. 250). Put differently, he urged the analyst neither to ratify or condemn the meaning of an analysand’s symptoms (as it has taken shape in his or her own mind), nor to try to alleviate these symptoms by suggesting a new meaning (as it appears in the mind of the analyst), but to elicit analytic effects through the intentional displacement of the analysand’s discourse.23 The notion “displacement” is synonymous here with the shifting connection between signifiers and also with the rhetorical trope of “metonymy,” which Lacan extracted, alongside that of “metaphor,” from the work of Roman Jakobson (E/S, pp. 156–8, 163–4).24 By demanding that the analyst formulate metonymical interpretations – undoing and not fortifying meaning, revealing and not concealing it – Lacan championed a purportedly more effective tactic for psychoanalytic treatment than any of the other, accepted techniques of interpretation (explanation, clarification, confrontation, reassurance, etc.). For Lacan insisted that all these techniques somehow rely on the substitution of the analyst’s signifiers for those of the analysand, that is to say, they all function within the dimension of metaphor, which invalidates their power over the symptom, because the latter is a metaphor in itself (E/S, p. 175). Indeed, because the symptom is a metaphor – the exchange of one signifier for another signifier or, in Freudian terms, the replacement of one repressed unconscious representation with another representation – it cannot subside by means of an analytic intervention that is metaphorical too.25

The clinical issues I am highlighting here are by no means marginal, much less alien to Lacan’s Structuralist project of psychoanalysis. On the contrary, the peculiarities of clinical psychoanalytic practice inform every single aspect of Lacan’s trajectory, from his earliest contributions on the family and the mirror stage to his final excursions on the intertwining of the real, the symbolic, and the imaginary. It is precisely this relentless clinical questioning rather than, say, the impact of Lévi-Straussian Structuralism, which triggered some of Lacan’s supplementary modifications of Saussure’s linguistic model. The most significant of these adjustments no doubt concerns his critique of the superiority of the language-system (langue), to the detriment of speech (parole) in the Course.26 In his ambition to devise a new scientific theory of language as an abstract system of signs embedded within a social context of human interactions, Saussure needed to make abstraction of the utterance, in which individuals employ the language code for expressing their thoughts and in which they rely on psycho-physical mechanisms of motor production and sensory reception. For Saussure, the only possible object for linguistics proper is therefore the language system (CGL, pp. 14, 20). As a psychoanalyst, Lacan disagreed with Saussure’s decision to relinquish the study of speech, because within psychoanalytic treatment the function of the analysand’s speech is more important than anything else. The signifier thus appeared in Lacan’s version of structural linguistics not as an element of the general language system but as the key element of the analysand’s speech.

Lacan’s emphasis on speech and his relative disregard for the language-system coincided with a sustained reflection upon the status of the subject in relation to the law of the symbolic order, or what Lacan designated as the Other. The subject should not be understood here as the unified, self-conscious being or the integrated personality so dear to many a psychologist, but as the subject of the unconscious – a subject that does not function as the center of human thought and action, but which inhabits the mind as an elusive agency, controlling yet uncontrollable.27 The reason for Lacan’s “subversion” of the classical, psychological notion of the subject is that during psychoanalytic treatment the analyst is not supposed to be concerned with how the analysand wittingly and willingly presents him- or herself in the twists and turns of his or her verbal productions, nor in the content of the analysand’s speech (what somebody is saying), but in the fact that something is being said from a place unknown to the analysand. “It speaks, and, no doubt, where it is least expected, namely, where there is pain,” Lacan stated in 1955 (E/S, p. 125). In keeping with Freud’s formula that patients suffer from “thoughts without knowing anything about them,” Lacan subsequently stipulated that the unconscious is a body of knowledge which expresses itself in various formations (dreams, slips, symptoms) without this knowledge being operated by a conscious regulator. Analytic treatment rests on the manipulation of the analysand’s unconscious thoughts and as such it should reach beyond what is said and how it is being said, towards an investigation of where things are being said from and who, if anybody, is actually saying it. What the analysand says is but a semblance and cannot be dissociated from what the analyst hears in his or her own understanding of the words; the very process of saying is much more important than the form of the productions in which it results.28 Throughout his work Lacan insisted on this point, deploring the fact that many analysts just continued to devote all their attention to understanding the content of the analysand’s message.

Borrowing another set of concepts from Jakobson’s research, Lacan also mapped out the antagonism between self-conscious identity and unconscious subject across the two poles of the opposition between the subject of the statement (sujet de l’énoncé) and the subject of the enunciation (sujet de l’énonciation). Freud’s famous joke of the two Jews who meet at a station in Galicia still serves as an excellent example of what Lacan was trying to demonstrate here. When the first Jew – let us call him Moshe – asks the second, who will go by the name of Mordechai, “So where are you going?” Mordechai says, “I am going to Cracow.” This message instantly infuriates Moshe, who exclaims: “You’re a dirty liar, Mordechai, because you are only telling me you’re going to Cracow in order to make me believe that you’re going to Lemberg, but I happen to know that you are going to Cracow!” (SE 8, p. 115). Of course, the joke is that Moshe accuses Mordechai of being a liar, whereas what Mordechai says is a truthful description of his journey plan. Moshe acknowledges that the subject of the statement is telling the truth about himself – “I know you’re going to Cracow” – but he also pinpoints the deceitful intention behind Mordechai’s statement, which reveals the subject of the enunciation: “Your true intention is to deceive me.” Mordechai may or may not have been aware of his intention, the fact of the matter is that Moshe acknowledges the presence of another subject behind the subject of the statement.

As a postulate, the subject of the enunciation implies that the subject of the statement (the personal pronoun or name with which the speaker identifies in his or her message) is continuously pervaded by another dimension of speech, another location of thought. However strongly somebody may identify with the subject of the statement, we have good reason to believe that the utterance is also coming from somewhere else than the place which the message has defined as the locus of emission. More concretely, if an analysand says, “I am doomed to ruin every relationship I am engaged in,” the analyst need not bother very much about the grammatical structure and semantic value of the message, but ought to concentrate on the fact that something is being said from a particular place, the exact source and intention of which remain unclear and require further exploration. When the analysand is saying, “I am doomed, etc.,” the subject of the enunciation is not necessarily herself. The statement may very well represent the discourse of her mother and she may easily produce these words for the analyst to believe that they are hers and for him to try to convince her that she is not doomed at all.

When Lacan embraced structural linguistics to advance the practice of Freudian psychoanalysis, he was hardly concerned with the type of questions Saussure and Jakobson were interested in, namely those related to the study of language as an abstract functional system linking sound and meaning. And despite his high regard for Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology, it is fair to say that he was neither involved in the study of how rules of kinship, the classification of natural phenomena, and the deployment of myths reflect the organization of the human mind and vice versa. What mattered more than anything else to Lacan, considering the specific nature of psychoanalytic praxis, was the establishment of a science of the subject – not the self-contained subject of consciousness but the ephemeral subject of the unconscious.

It probably does not come as a surprise, then, that as his work progressed Lacan became more and more skeptical about the value of linguistics for psychoanalysis. In December 1972, during a crucial session of his seminar Encore, which was notably attended by Jakobson, he eventually admitted that in order to capture something of the Freudian unconscious and its subject, linguistics does not prove very helpful. Insofar as language is indeed of the utmost importance to the psychoanalyst, what is needed, Lacan quipped, is not the science of linguistics, but “linguisteria” (linguisterie), a certain (per)version of linguistics which takes account of the process of saying and its relation to the (subject of the) unconscious (S XX, p. 15).29 In “L’Etourdit,” the message was even more provocative: “For linguistics on the other hand does not open up anything for analysis, and even the support I have taken from Jakobson isn’t . . . of the order of retrospective effect [après-coup], but of repercussion [contrecoup] – to the benefit, and secondary-sayingly [second-dire], of linguistics.”30 In other words, instead of conceding that psychoanalysis had progressed by virtue of its marriage to structural linguistics, Lacan claimed that linguistic science itself would benefit from his psychoanalytic espousal of Structuralist ideas.

It is tempting to entertain the idea that Lacan’s gradual departure from structural linguistics and his concurrent divergence from the Structuralist paradigm in general, fostered the ascendancy of topological investigations in his work. Topology is a branch of mathematics which came to prominence towards the end of the nineteenth century and which deals with those aspects of geometrical figures that remain invariant when they are being transformed. As such, a circle and an ellipse are considered topologically equivalent because the former can be transformed into the latter through a process of continuous deformation – that is, a process which does not involve cutting and/or pasting.31 References to topology abound in Lacan’s texts, and topological surfaces such as the Möbius strip, the Klein bottle, the torus, and the cross-cap emerged intermittently in his seminars from the early 1960s until the early 1970s. Yet during the last decade of his life, from 1971 to 1981, Lacan spent more time than ever studying the relevance of these surfaces for the formulation of a scientific theory of psychoanalysis. After having discovered the so-called “Borromean knot” during the winter of 1972, Lacan would often spend hours and hours weaving ends of rope and drawing complicated diagrams on small pieces of paper.32 His preoccupation with topological transformations became so overwhelming that during his seminar of 1978–79 he even silenced his own voice in favor of the practice of writing and drawing, treating his audience to the speechless creation of intricate knots on the blackboard.

Does topology supplant Structuralism in Lacan’s intellectual itinerary? Does topology address the problems Lacan identified within structural linguistics? Does it constitute a more scientific approach to the practice of psychoanalysis than the doctrine of Structuralism? Is it more in tune with the subject of the unconscious than the linguistic research tradition? Within the space of this paper, I can only touch the surface of these issues, due to the fact that they put at stake the entire epistemology of Lacanian psychoanalysis, the transmission of psychoanalytic knowledge within and outside clinical practice, and the conflictual relationship between speech and writing. Lacking the space for developing the long reply to the above questions, I shall restrict myself to giving the short answer, which can only be “yes and no.”

Let me start with the affirmative side of the answer. Topology does indeed replace structural linguistics within Lacan’s theoretical advancements of the 1970s. To verify this claim one need not look further – although I can imagine that many readers of Lacan will already situate this point way beyond their intellectual horizon – than his 1972 text “L’Etourdit.” Juxtaposed to his explicit devaluation of linguistics is the affirmation that topology constitutes the essential reference and prime contributing force to the analytic discourse. Unlike linguistics, Lacan contended, topology is not “made for guiding us” in the structure of the unconscious. For topology is the structure itself, which entails that (unlike linguistics) it is not a metaphor for the structure.33 It should be noted here that Lacan did not define topological transformations in general as the equivalent of unconscious structure, but only those that apply to non-spherical objects, such as the torus and the cross-cap (projective plane). Topology’s advantage over linguistics thus comes exclusively from its non-spherical applications, that is to say those transformations implemented on objects without a center. If Lacan’s critique of structural linguistics stemmed largely from the latter’s inherent presupposition of a total and totalizing language system centered around the primordial incidence of the signifier, his recourse to topology was meant to account for the very absence of a nodal point in the unconscious. Whereas linguistics did make ample room for the study of structural transformations – as exemplified by Lévi-Strauss’s massive, four-volume “science of mythology” series – it was, at least according to Lacan, incapable of explaining the occurrence of these transformations without continuing to presuppose the presence of a creative or transformative agency. In the unconscious, however, the subject is real; it is the very absence of being that rules the organization and transformation of knowledge. This is what Lacan endeavored to demonstrate with his non-spherical topology.

The negative side of the answer is slightly more difficult to explain. Topology does not replace structural linguistics within Lacan’s theoretical advancements of the 1970s, partly because topology emphasizes writing to the detriment of speech, partly because topology is equally at risk of functioning as a mere metaphor for the mechanisms of speech and language in the unconscious. During the early to mid 1970s Lacan engaged in a lengthy paean to the virtues of writing, because he believed that, by contrast with the signifier, writing operates within the dimension of the real and is therefore able to guarantee a complete transmission of knowledge.34 In his seminar Encore, Lacan confessed unreservedly to his faith in the ideal of mathematical formalizations, because he considered them to be transmitted without the interference of meaning (S XX, pp. 108, 100). For many years, writing in its various avatars (the letter, algebraic formula, topological figures, drawings of Borromean knots) was Lacan’s preferred mode of demonstration, and he relentlessly imbued his followers with his latest achievements in the realm of knot theory. Yet what he seemed to forget at this stage is that psychoanalytic practice does not rely on an exchange of letters, but on the production of speech. Topology may have taken Lacan to the real heart of the psychoanalytic experience, it also drove him away from its necessary means and principal power.

At the same time when Lacan expressed his confidence in formalization, he also divulged that mathematical formulae cannot be transmitted without language, so that the re-emergence of meaning presents an ongoing threat to the possibility of an unambiguous, integral transmission of knowledge. Nonetheless, Lacan continued to step up his campaign for the acknowledgement of writing, mathematical formalization, and topology until the end of his 1976–7 seminar, when he admitted that the entire project was likely to fail in light of the inevitable interference of meaning.35 Towards the very end of his career, Lacan expressed this failure even more strongly, when formulating the most trenchant self-criticism of his entire life’s work and admitting to the fact that instead of conveying the real of psychoanalytic experience the Borromean knot had just proved to be an inappropriate metaphor. In this way, he opened up new avenues for a return to the study of speech and language in the unconscious, not via the rejuvenation of structural linguistics, but possibly via another, more psychoanalytically attuned theory of language. Unfortunately, Lacan did not live long enough to embark on this new, challenging project.

1. The reader will find the best analysis of Lacan’s position within the Structuralist movement in François Dosse, History of Structuralism, 2 vols. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997). For other informative accounts, see Malcolm Bowie, “Jacques Lacan,” Structuralism and Since: From Lévi-Strauss to Derrida, ed. John Sturrock (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), Richard Harland, Superstructuralism: The Philosophy of Structuralism and Post-Structuralism (London: Methuen, 1987), and (less recent but still valuable)Fredric Jameson, The Prison-House of Language: A Critical Account of Structuralism and Russian Formalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972).

2. See Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, ed. Charles Bally and Albert Séchehaye in collaboration with Albert Riedlinger, trans. Wade Baskin (London: Peter Owen, 1960). Hereafter cited in the text as CGL. Saussure’s book is also available in a more recent translation by Roy Harris, yet owing to its idiosyncratic rendering of some of Saussure’s key terms, the reader will find this version quite difficult to use, especially in light of the fact that the bulk of the secondary literature on Saussurean linguistics has not adopted Harris’ options.

3. Dosse, History of Structuralism, vol. 1, p. 76.

4. See Jean Laplanche and Serge Leclaire, “The unconscious: A psychoanalytic study,” trans. Patrick Coleman, Yale French Studies 48 (1972), pp. 118–75. For Lacan’s criticism of this text, see his “Position of the unconscious,” Reading Seminar IX: Lacan’s Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, eds. Richard Feldstein, Bruce Fink, and Maire Jaanus, trans. Bruce Fink (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), pp. 259–82, “Preface by Jacques Lacan,” Anika Lemaire, Jacques Lacan, trans. David Macey (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1977), pp. vii–xv, and “Radiophonie,” Scilicet 2/3 (1970), pp. 55–99.

5. Lacan, “Radiophonie,” p. 68.

6. See Jean-Luc Nancy and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, The Title of the Letter: A Reading of Lacan, trans. François Raffoul and David Pettigrew (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992).

7. See Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, corrected edition, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), and Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass (London: Routledge, 1977).

8. See Claude Lévi-Strauss, “Preface,” Roman Jakobson, Six Lectures on Sound and Meaning, trans. John Mepham (Hassocks: Harvester Press, 1978).

9. See, for example, Didier Eribon, Conversations with Claude Lévi-Strauss, trans. Paula Wissing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

10. See Lévi-Strauss, “Preface,” p. xx.

11. Claude Lévi-Strauss, Introduction to the Work of Marcel Mauss, trans. Felicity Baker (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987), p. 35.

14. See Jacques Lacan, “Lituraterre,” Autres écrits (Paris: Seuil, 2001), p. 14, and “Radiophonie,” p. 55.

15. The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess 1887–1904, ed. and trans. Jeffrey Masson (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985), p. x.

16. See Sigmund Freud, On Aphasia, trans. Erwin Stengel (New York: International Universities Press, 1953). For a judicious discussion of this book and its historical context, see Valerie D. Greenberg, Freud and his Aphasia Book: Language and the Sources of Psychoanalysis (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997). For a more encompassing yet equally astute evaluation of the importance of Freud’s linguistic ideas for the emergence of psychoanalysis, see John Forrester, Language and the Origins of Psychoanalysis, 2nd edn. (London: Palgrave, 2001). For an in-depth treatment of Freud’s general theory of symbolism in relation to the analysis of unconscious productions, see Agnes Petocz, Freud, Psychoanalysis and Symbolism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

17. Claude Lévi-Strauss, “The effectiveness of symbols” (1949), Structural Anthropology, trans. Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf (New York: Basic Books, 1963), pp. 186–205.

18. The formula appeared for the first time, in rudimentary form, in Lacan’s seminar of 1955–56: “Translating Freud, we say – the unconscious is a language” (S III, p. 11).

19. Jacques Lacan, “Of structure as an inmixing of an otherness prerequisite to any Subject whatever” (1966), The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man: The Structuralist Controversy, eds. Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1970), p. 188.

20. Jacques Lacan, “Science and Truth” (1965), trans. Bruce Fink, Newsletter of the Freudian Field 3, nos. 1/2, pp. 4–29.

21. Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (La Pensée sauvage) (1962) (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1966).

22. For Freud’s position on the scientific status of psychoanalysis, see in particular Lecture 35, “The question of a Weltanschauung,” New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis (SE 22, pp. 158–82).

23. Lacan, “Radiophonie,” p. 59.

24. See also Roman Jakobson, “Two aspects of language and two types of aphasic disturbance,” Roman Jakobson and Morris Halle, Fundamentals of Language (The Hague: Mouton, 1956), pp. 55–82.

25. For a more detailed discussion of these principles, see my Jacques Lacan and the Freudian Practice of Psychoanalysis (London and Philadelphia: Brunner-Routledge, 2000), pp. 153–83.

26. The reader should note that Baskin has translated the term parole as “speaking,” reserving “speech” rather confusingly for langage. Harris has adopted “speech” for parole, but fails to distinguish consistently between langue and langage. Sometimes he translates langue as “the language itself,” and sometimes as “a language system” and “language structure,” thus introducing a notion (that of structure) which has no conceptual status in Saussure’s work. At other times he also renders langue erroneously as “individual languages.”

27. For Lacan’s distinction between the subject of psychoanalysis and the subject of psychology, see the opening pages of “The subversion of the subject and the dialectic of desire in the Freudian unconscious” (E/S, pp. 292–325). For more detailed discussions of Lacan’s concept of the subject, see Bruce Fink, The Lacanian Subject: Between Language and Jouissance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), and Paul Verhaeghe, “Causation and destitution of a pre-ontological non-entity: On the Lacanian subject,” Key Concepts of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, ed. Dany Nobus (New York: The Other Press, 1999), pp. 164–89.

28. Jacques Lacan, Le Séminaire XIX . . . ou pire (1971–72), session of June 21, 1972. Unpublished. Also, see Jacques Lacan, “L’Etourdit” (1972), Scilicet 4 (1973), pp. 5–52. In the latter text Lacan launched the formula “What one may be saying remains forgotten behind what is being said in what is heard.”

29. While Fink has translated linguisterie as “linguistricks” and mentions “linguistrickery” as another solution (see S XX, p. 15, n.3) in opting for “linguisteria” I have tried to render what I believe to be the gist of Lacan’s portmanteau word: a combination of linguistics and hysteria or, even better, a hysterical transformation of linguistics. For a more extensive discussion of Lacan’s alternative linguistics, see Jean-Claude Milner, “De la linguistique à la linguisterie,” Lacan, l’écrit, l’image, ed. Ecole de la cause freudienne (Paris: Flammarion, 2000), pp. 7–25, and Cyril Veken, “La Linguistique de Lacan,” La Célibataire – Revue de psychanalyse 4 (2000), pp. 211–28.

30. Lacan, “L’Etourdit,” p. 46.

31. For a concise description of the history of topology and its place within Lacanian theory, see Nathalie Charraud, “Topology: the Möbius strip between torus and cross-cap,” A Compendium of Lacanian Terms, eds. Huguette Glowinski, Zita M. Marks, and Sara Murphy (London: Free Association Books, 2001), pp. 204–10.

32. For an excellent discussion of Lacan’s “affair” with the Borromean knot, see Luke Thurston, “Ineluctable nodalities: On the Borromean knot,” Key Concepts of Lacanian Psychoanalysis, ed. Dany Nobus (New York: The Other Press, 1999).

33. Lacan, “L’Etourdit,” pp. 28, 40.

34. See, for instance, Jacques Lacan, “Yale University, Kanzer Seminar (24 novembre 1975),” Scilicet 6/7 (1976), pp. 7–31.

35. See Jacques Lacan, “Le Séminaire XXIV: L’insu-que-sait de l’une bévue s’aile à mourre” (1976–77), Ornicar? 17/18 (1979), pp. 7–23. For a more detailed account of Lacan’s contrived engagement with writing and formalization during the 1970s, see Dany Nobus, “Littorical reading: Lacan, Derrida and the analytic production of chaff,” JPCS: Journal for the Psychoanalysis of Culture and Society 6/2 (2001), pp. 279–88.