I remember the yellow cornfields … Saugatuck

in summer … oaks … dark birches … wild

pines … Those things cohere.

JOAN MITCHELL

On Saturday mornings when she wasn’t competing, Joan would meet a group of girlfriends downtown for lunch, followed by an early matinee. On Saturday nights, she and Sally double-dated brothers Milton and Malcolm Hughes. And at Parker, she was forever charging across Clark Street to the Belden drugstore for gossip, chocolate Cokes, and cigarettes, so loving her weeds that the school newspaper’s waggish “Rumor Humor” columnist assigned her the theme song (a variant on the popular show tune) “Smoke Gets in My Eyes.” All the same, Joan kept slightly apart. Wanting to give skating and painting her all, she passed on the plays, school newspaper activities, and political clubs that dominated extracurricular life. Because of skating, she missed so much school in her junior and senior years that Parker considered expelling her. Her contemptuous attitude toward teachers she judged ineffectual also came up in faculty discussions of Joan’s case—“contemptuous or frightened,” clarifies a schoolmate—but she had her defenders, and, in the end, she was permitted to stay. Her fellow students perceived Joan as “bright, poignant, witty, subtle” and “marching to her own drummer.”

Less subtly, she was gleefully shocking her parents and their friends by flinging around words like “fuck,” “piss,” “damn,” “penis,” and her favorite, “balls,” this last earning Sally’s nickname for her, “J. Balls.” In that era such longshoreman’s language from the mouths of sub-debutantes was nothing short of scandalous. (Consider that after Lillian Smith’s 1944 best seller about interracial marriage, Strange Fruit, was banned for obscenity in Massachusetts—one character uses the word “fucking”—its publishers’ legal challenge collapsed when their attorney could not bring himself to put the offending word in a brief or pronounce it in court.)

More serious disagreements had also begun to roil Mitchell family life. Her staunchly conservative father infuriated Joan by fulminating against Roosevelt and all liberals, clipping editorials from the then right-wing Chicago Daily Tribune and leaving them on her pillow. A Jew-hater too, he fumed over the fact that Parker had become a magnet for Jewish students. Moreover, he forbade his daughters to ride the bus to school since that would mean mixing with Negroes. Even by the unenlightened standards of 1940s Chicago, Jimmie Mitchell had a reputation as a fierce bigot. Marion was more discreetly racist and anti-Semitic. In one of her novels, however, a character muses that all intelligent Jews have the makings of psychoanalysts, versed as they are in “the unusual, the devious, the elusive.” In another, her murder victim is an aging rink rat with “eyes with an oriental slant,” “a wolf’s nose,” “dark-skinned hands,” and a stocky frame emitting an “animal odor.”

Her father’s rancor over her beloved Parker was particularly hurtful to Joan. Waspy and solvent in the 1920s, the school had hit hard times when its founder scaled back her support and enrollment plummeted during the Depression. Doubly motivated by pragmatism and principle, Parker began recruiting more widely, and, by the mid-1930s, half the student body was Jewish. Joan’s schoolmate, thirteen-year-old John Holabird, encountered Dr. Mitchell’s indignation about Jews at Parker when he consulted the physician for boils. In the midst of issuing instructions about hot compresses and poultices of gentian violet, the doctor abruptly leaned over the young man and peevishly asked, “Isn’t it hard to be at Parker with all those Jews?” Unnerved at the time, John could not bring himself to mention the incident to Joan until many years later. Her clipped response: “That’s impossible.” All her life, Joan would repudiate racism and anti-Semitism (though some mistook her blunt political incorrectness for just that) and delight in raking racists and anti-Semites over the coals. But by the time her former schoolmate opened up to her, she preferred, all things considered, not to rock the pedestal upon which she had placed her father. A gracious man, Holabird tells this story with a bemused wince, as if the memory of Jimmie and Joan Mitchell still provokes mild heartburn, a reaction not unlike that of Joan’s later best friend Zuka Mitelberg, who perceived “a flaw in that family. There was really something wrong in that family. It was like a gene in them. Of hatred. And they were all wonderful charmers.”

Not only had Parker recruited Jewish students, but also it had hired Jewish teachers, some of them refugees from Nazi Europe, like Joan’s new French teacher, Helen Richard.

Having fled their native Austria, Helen and her husband, Edgar, a science teacher, had landed in Massachusetts, from where they were recruited to Parker. The minute they arrived, they knew they belonged, the institution’s ethos of intellectual rigor and strong-minded individualism a perfect match for theirs.

A tiny (five-foot-two) actress manquée, Helen Richard, affectionately known as Madamie, leavened her demand for excellence with a bubbly joie de vivre. If the vocabulary word was “balayer,” she swung an imaginary broom; if the lesson was the Moulin Rouge, she picked up her skirts and cancanned across the classroom, even though she had just given birth to twins. Parkerites adored her, not least Joan.

Speaking French was part of her Francophile father’s agenda for Joan, but she too gravitated to the language of Verlaine and Proust, even though she had to wrestle with languages (she was also taking Latin), in part because the color cues that worked for her in English lapsed in other tongues. Her French “bleu,” for instance, was less intensely blue, less alive, than her English “blue.” Blueness inhered not only in the sound of the first letter (Joan’s b was the color of a gas flame) but also in the concept, and thus the Frenchness of “bleu” turned the English word’s energized hue into something moody and hermetic. The entire French language, in fact, proved slightly amiss, as if, expecting something sweet, Joan had chomped down on something salty instead and had to turn it over on her tongue in order to detect its true flavor.

Such difficulties aside, Joan delighted in Madamie’s enthusiasm for all things French, literary, and avant-garde. Thus writer André Gide, the subject of Richard’s doctoral dissertation at the Sorbonne, came to Joan’s attention. Gide makes a strong case for seeking the authentic self, mistrusting received ideas, and staying open to life’s possibilities; he lays out the concept of the gratuitous act, the act, if such exists, unfettered by rationality and self-interest. How could such ideas, utterly foreign to the way in which she was raised, fail to impress the adolescent?

As much as Gide, Freud was an intellectual hero to Joan’s Viennese émigré teacher. Unfamiliar to the Chicagoan on the street (the idea of a talking cure, so patently un-midwestern), psychoanalysis had nonetheless secured a place in psychiatric practice and attracted the attention of the intelligentsia. A star student in Alfred Adler’s advanced psychology class, Joan was familiar with Freud’s theories, yet Helen Richard may have been the first to bring them to bear on the adolescent’s own inner turmoil. Joan realized that her demons could be disempowered and hidden meanings wrested from life. Psychoanalysis was not self-indulgence but rather a form of authenticity, even heroism.

Madamie’s empathy and understanding also proved a godsend. This first of her surrogate mothers spoke with her unpuritanically about boys, moods, sex, and parents. At home, Marion accused Joan of having B.O. and of lying about her hygiene; Madamie had a European matter-of-factness about the body. Marion instructed Joan to inquire politely about people’s ailments, whether she cared or not; Madamie made no bones about her horror of falseness.

Nor did Joan, who refused to tell the little lies that serve as social glue. She also regularly knocked her teachers when they tried to tell her what to think or when she simply wanted to “get their goats.” Many still felt she should be expelled.

Not Madamie. “Joanie was magnificent—and arrogant,” Helen Richard recalled half a century later. “We had a wonderful relationship. I loved her very much.” Richard was speaking to her son, Washington Post art critic Paul Richard, who had recently met sixty-three-year-old Mitchell at a reception for her exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. When he told the artist who he was, she burst into tears—in the midst of the crowd—gasping, “Your mother saved my life! She taught me passion—I really mean that.”

Another new addition to Parker’s faculty, artist Malcolm Hackett, also taught passion. The kind of man adults tag as ersatz but adolescents worship, Hackett “held court” in the art room, where he opened “vast visions to the few of us who listened,” according to Joan, who had a huge crush on her teacher. She was not alone. “Oh, Christ! Malcolm Hackett!” offers painter Herbert Katzman, who studied with Hackett from age eleven. “I would have traded forty of my fathers for one Malcolm Hackett!”

The Hackett mystique began with his tales of dropping out of the University of Wisconsin and knocking around South America for seven years, an adventure capped with a pilgrimage to Gauguin’s Tahiti, where the locals had supposedly offered him their virgin daughters. Back in Illinois, he had earned a degree from the School of the Art Institute, then taught here and there while daubing buttery nudes and earnest landscapes for the WPA easel project. At Parker, he played the role of perennial malcontent, scorning all but a few of the “mollycoddled” students and boycotting faculty meetings on grounds they were nothing but hot air.

A big man with a shock of slate-gray hair, wiry brows, a rugged face, and an oversized mustache of the type that requires crumbing after lunch, Hackett affected plaid lumbermen’s shirts, baggy trousers, and painters’ smocks. Reacting to the American stereotype of the artist as clubwoman’s lapdog, he anticipated a new stereotype: the artist as manly beer-drinking joe. Paul Richard remembers Hackett as “a cartoon Abstract Expressionist,” a Cedar Tavern–type avant la lettre, “hanging out and getting into fistfights.”

Hackett’s teaching methods too were prone to caricature. He did assign drawing from the skeleton and encourage those so inspired to paint the setup: a jug, a plant, a wineglass, and a lemon or two artfully arranged on a cloth-draped table. But he also allowed his acolytes simply to hang around the art room, inhaling its perfume of linseed oil and talking Art. Students did not complete a semester with Malcolm Hackett having learned to paint. Yet in one voice they credit Hackett with putting them on the road to artistic maturity thanks, in part, to the rules he laid down in an easy, authoritative manner.

Rule number one: In order to develop taste and avoid compromising your talent, allow yourself to be influenced by only the greatest artists. Joan had been painting still lifes beholden to Cézanne (whose work she knew from the Art Institute) for their radically upturned tabletops and attention to structure. Pushing her to expand her horizons and move beyond her careful little-girl manner, Hackett taught her to admire the work of Titian, Goya, Manet, and Soutine and insisted she see the Arts Club’s exhibition of Austrian Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka’s agitated, high-keyed panoramic cityscapes and psychologically complex portraits.

Second, dictated Hackett, art is not a career but an identity. You must present yourself—and dress—like an artist. Here Joan was of two minds. She adored beautiful clothes, like the perfectly pressed skirts she wheedled from Sally (her own typically amounting to wrinkled messes) and the stylish junior evening gowns and print dresses she purchased using her generous charge account at Marshall Field. But she also loved knockaround shirts and dungarees, which in those years still had the power to upset status-conscious midwesterners like Jimmie who had been raised on the farm—from dungarees to dungarees in only two generations. Wont to emerge from primping sessions at the bathroom mirror flaunting scarlet lips, she would growl with principled indignation at an artist girlfriend who indulged in the same: “Wipe that lipstick off your mouth!”

Finally, Hackett decreed that you must endure poverty and pain for your art. His concept of artists as a race of van Goghs hewed to the Romantic tenet that great art requires great suffering, a fate preordained for those who open themselves up to the mysteries of love and inspiration in this philistine world. Joan seized upon her teacher’s words, pointing as they did to a way of sublimating her aloneness and difference: artists were supposed to be alienated. Measuring Hackett’s vision of art against her father’s hobbyism, she found Jimmie diminished.

In her junior and senior years, Joan ran around with the art clique: Lucia Hathaway (her rival for teacher’s pet), Connie Joerns, and Connie’s sort-of boyfriend, tall, jolly, topaz-eyed Edward St. John Gorey. For Ted Gorey too, Malcolm Hackett served as a compass. Under the older man’s tutelage, the “fact that I couldn’t paint for beans” seemed curiously irrelevant to his future as an artist. Though a newcomer to Joan’s Class of ’42, Ted had claimed a central position in that class, owing to a jaunty individualism that took the form of odd stunts like painting his toenails green, then strolling barefoot down Michigan Avenue. Already he was obsessively drawing little men in raccoon coats, a signature of the long career as an artist and writer that would bring macabre cult classics like The Gashlycrumb Tinies (an abecedary of ill-starred children, one of whom toddles over the brink of life with each passing letter) and the introductory sequence of the PBS series Mystery!

Two exceptional intelligences and strong personalities, Joan and Ted frequently “did stuff” together. After graduation, each would blow into Chicago around the holidays, and they would get together for an evening or two, crabbing about life as they killed a bottle of Scotch. At one Parker class reunion, they sauntered into the old gym, noses stuck in the air, then sauntered back out again without saying hello to anyone, as if they didn’t want to risk infection by the bourgeois element. But there was also a mutually undercutting edge to their friendship. According to Connie Joerns, who remained close to Gorey all his life, “Ted was intrigued by Joan” yet “thought her paintings were absolute garbage, and he continued to think that.” On the other hand, Gorey is on record as labeling everybody after Cézanne “a lot of hogwash.”

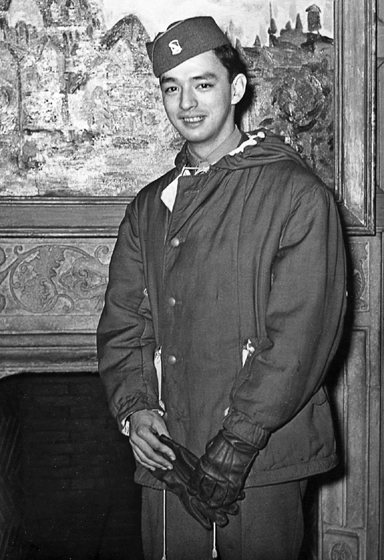

Joan also remained close to best friend Joan Van Buren. But perhaps her most vital high school relationship was with dreamy, bitter, brilliant, and wild Timmy Osato, the son of Japanese photographer Shoji Osato and rebellious Irish Quebecois blue blood Francis Fitzpatrick, and the brat brother of Ballets Russes dancer Sono Osato and feisty beauty Teru Osato, Bennington Class of ’43. Timmy had no problem holding up his end of this extraordinary family. With dark-pearl eyes, delicate features, smooth skin, and raven hair, he was as stunning as he was brainy. A top history student, Timmy performed on the radio every Wednesday evening as one of the popular WTTW “child genius” Quiz Kids. Smitten with Parker’s star “figure (ah!) skater,” he played the daredevil around “the Mighty Mitchell” at every opportunity. When Joan threw a party, Timmy and another classmate, future real estate magnate Jerry Wexler, hung off her tenth-floor balcony “just to show they could.”

Then, in the middle of their senior year, Japan unleashed its devastating attack on Pearl Harbor, killing 2,300 Americans and stripping Timmy Osato of his peace of mind. His father was interned, and Timmy burned with self-hatred because of his Japanese blood. He left Parker, where rumors flew about his fate. Eighteen months later, Joan received a letter (“Dear Enigma …”) from Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and the two began corresponding. Tim had joined the segregated 442nd Nisei Regiment, the most decorated U.S. combat unit, with which he would serve in Europe, where he won the Bronze Star. After the war, he entered Yale and wrote again, from New Haven: “I suppose it’s senseless trying to preserve images of saddleshoes and middy blouses, leopard-skin coats and the fragility of an inexplicable tenderness—but then I have never been sensible, and I shall probably be quite blue if you decide to ignore me.” Joan did not. The two became sporadic lovers. Of Osato, Joan’s later husband, Barney Rosset, once said, “He was the real love of Joan’s life.” That he is all but absent from her official biography attests to both the fitfulness of their encounters and her deeply private nature.

Tim Osato, 1940s (Illustration credit 4.1)

On January 16, 1942, the battle for the Midwest women’s senior figure skating championship got underway in Chicago. Having again laid her shoulder to intense summer training with Gus Lussi at Lake Placid, Joan was in top form. And Bobby was favored to win both the Midwest and U.S. men’s titles. The two skipped pairs competition in order to focus on singles.

The women’s event opened with the compulsory school figures, which counted for 60 percent. At day’s end, Mitchell led by less than a point, with four rivals, notably the 1940 U.S. champion, Mary Louise Premer of St. Paul, in hot pursuit. Politely attentive that Friday, the crowd warmed up on Saturday as, one by one, the competitors cut loose with their free-skating routines. For most of the day first place was a coin toss between Mitchell and Premer, but Joan delivered her finest and eventually bested her opponent. With reporters’ flashbulbs popping, she claimed the trophy of 1942 figure skating queen of the Midwest. The pictures catch her capable shoulders, thighs like Lincoln Logs, heavily scuffed skates, and flush of exertion and joy.

This victory working to her psychological advantage, Joan was poised to place in the fast-approaching Nationals, moved at the last minute from California to Chicago because of wartime restrictions on travel to the West Coast. Among her opponents, however, loomed two of the great American skaters, defending senior champion Jane Vaughn Sullivan and future six-time national titleholder Gretchen Merrill, both of whom are today enshrined in the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame.

Normally a paragon of steel-meets-ice mental toughness—picture her arching into a powerful warm-up stretch while fixing her rivals with a withering stare—Joan shrank back. Wisely perhaps, but atypically, she ducked the full challenge by registering for the junior rather than the senior competition, thus enhancing her chances at a national singles prize. In that era, categories were based solely on skill level as determined by USFSA tests; dropping back one category was legal and not uncommon.

The championship opened with the school figures, in which Joan placed fifth. Performing under intense pressure during the free-skating segment that followed, she fell and seriously damaged her kneecap. But even before this accident she had hit heavy weather. One Dorothy Goos, the thirteen-year-old daughter of a Bronx electrician, had sailed through a performance that “verged on the sensational”—double flip, double loop, double salchow, lutz, split, and on and on—earning her close to perfect scores and making her the sweetheart of the day. Everyone knows that ice is pitiless and crowds are fickle, yet Joan’s fourth-place finish behind a kid in the juniors at her own Chicago Arena would have felt raw and humiliating. So quickly knocked off her pedestal! Her fans’ attention was now glued to Bobby and Jane Vaughn Sullivan, the new national champs, and to the adorable Dorothy Goos. This had been Joan’s best shot at the national prize for which she had worked hard for years. Within hours, it was over. She kept her feelings to herself, but eventually the episode reinforced her hardheaded, self-coaching realism. You don’t indulge what-ifs. You confront the facts. You go on.

Officially, Joan gave up skating because of the knee injury, but her real reasons were more complex. On the practical side, college would complicate her access to a suitable trainer and rink. The bigger picture also took in the war. Boys she knew from school were rushing headlong into combat, which was real, she felt, in a way that skating was not. And what did she want? She wasn’t going to turn pro and run around the country in anything as corny as the Ice Capades. Skating wasn’t her future. It was only hedging her bets. Joan was going to do what she was going to do—and that was painting, and the hell with it.

Five years of competitive skating would have brought to Joan’s attention what historian Susan Cahn terms the “underlying tension in American women’s sport, the contradictory relationship between athleticism and womanhood.” Raised in many ways like a boy and educated at that rarest of American schools where something like gender equality prevailed, Joan owed to skating the full realization that, as her father always said, girl equals second class. She lived in a man’s world where even a “feminine” sport was contrived to ensure that a woman could never truly excel. For one thing, male skating was considered inherently more consequential than female skating. When both Bobby and Joan won midwestern senior titles, the Tribune had headlined, “BOBBY SPECHT TAKES FIGURE SKATING CROWN; Joan Mitchell wins Senior Women’s Title.” For another, different standards of value applied. A male skater “took a commanding lead,” proved himself “the boss,” or otherwise invaded and conquered; a female skater, in contrast, delivered an “intricate and beautiful” performance, as if the rink were an embroidery hoop, or proved “graceful,” as if it were a ballroom. Joan, not Bobby, appeared in the papers in the throes of a dance-like arabesque, the glittery spectacle of skating projected upon her body, not his. Joan loved looking but hated being looked at.

Men—her father, Gus, Bobby—had advanced Joan’s skating career, and men’s opinions counted, so it was men’s opinions Joan courted, a practice that would also mark her life as a painter. Artist Ellen Lanyon remembers how in the 1940s “women were subservient to men in the art world, and Joan made it her life’s business to show that she was not going to give in to this idea, that she was going to run with the pack, and she did!” Like the sports world, the art world assumed a contradiction between subjectivity and womanhood. Yet Joan lived in a place where gender did not operate: “on the inside” (in the words of French writer Nathalie Sarraute), where she was, “sex does not exist.”

After achieving success as a painter, Joan would keep publicly quiet about her skating past. Not that she wasn’t proud of it—has any other major American artist competed in sports at the national level?—but she considered the inevitable comparisons between skating and abstract painting irrelevant and trivializing. Noting the whiplash linearity of her work and the whispery gray, tallow, and pale blue palette she then favored, a few commentators in the early 1950s hit upon the skating conceit. Artist/critic Robert Goodnough, for one, asserted in an ArtNews review that Mitchell canvases “whirl in abstract activity,” resulting in “something like a sheet of ice into which linear movements are worked, like a skater performing acrobatic stunts”—thereby infuriating Joan.

From the perspective of late middle age, she did concede a commonality: “If you use your body [in painting] as you do in any sport, that’s all part of your coordination.” One could also draw parallels between skating and painting in terms of discipline and psychological release. The rare and exalted place of simultaneous concentration and self-forgetting that athletes call “the zone” bears a distinct resemblance to the painting nirvana that Joan sought: “Painting is a way of forgetting oneself. Sometimes I am totally involved. It’s like riding a bicycle with no hands. I call that state ‘no hands.’ I am in it. I am not there any more. It is a state of non-self-consciousness. It does not happen often. I am always hoping it might happen again. It is lovely.”

Arguably, too, though she never said so, the Lussi method seeded Joan’s process. At each stage of a painting, she looked hard, then approached the canvas with a clean plan of attack. “I don’t close my eyes and hope for the best,” she harrumphed. (Use mental rehearsal, Gus commanded.) Moreover, she was scrupulous about “accuracy,” a way of saying that every element had to be “meaningful and sensitive.” (Nothing hit or miss, said Gus.)

A few weeks after her seventeenth birthday, Joan hung up her skates with the thought, “I’ve won my last medal for you, Daddy.” It was like saying no to God.

A bright but distracted freshman at Sarah Lawrence, in Bronxville, New York, the flawlessly put-together Miss Sally Mitchell made her debut that summer on the right weekend at the right club with the right guests, among them the junior Wrigleys, Ryersons, Armours, Swifts, and Wackers. Sally knew exactly what she wanted from Chicago society; Joan, on the other hand, agonized. She poured at teas, dated preppy types, attended sub-debutante dances, stood in receiving lines, was written up in the society columns, and took pleasure in her privileged life, yet she often felt bored or appalled by a way of living exemplified by Lake Forest and its “S.R. [Social Register] phoniness.” What position should an artist take toward the world of fashion? Her mother’s friends included highly accomplished people of means committed to advancing modernism, people Hackett nonetheless held in contempt. Joan’s erratic friendship with the dynamic, funny, and popular Joan Van Buren (later a society columnist for the Chicago Daily Tribune) betokens her confusion; the two adored each other, hated each other and weren’t speaking, then adored each other again.

Impatient to get on with her painting, Joan was turning up her nose at the idea of attending the “right” college (although she would not be caught dead at the “wrong” college) and arguing for art school instead. But, believing her too young, Jimmie turned thumbs down. Of the three colleges to which Joan had been accepted, she chose Bennington. Again Jimmie refused: too arty. Having recently grabbed a few hours from skating in Philadelphia to tour the Bryn Mawr campus, she had pronounced it “death warmed over.” That left Smith.

In those days, a journey from Chicago to Northampton, Massachusetts, meant the New York Central sleeper through Gary (where factories belched smoke day and night because of the war), then on to Cleveland, Albany, and Springfield, the link with a commuter train for the short push to Northampton. A midwesterner’s first impressions of Smith’s hometown were typically of the quaint shops along Main Street, the stately houses on Elm, and the campus itself, serene and Emersonian. Hung each fall in splendid autumnal hues, Smith distilled eastern-ness like the parlor of a great house.

In 1942, however, Smith lacked some of its usual tranquility. Among the first colleges to host the Navy’s WAVES program to train women for support positions and thus free men for combat overseas, it swarmed with two thousand crisply uniformed female sailors pounding the sidewalks in a hup-two-three-four beat. The school’s staff of white-aproned maids had vanished, and Smithies now made their own beds, wielded their own mops, and slung their own creamed chipped beef on toast and broiled tomatoes with bread crumbs (aka “train wreck”). Student heat cops patrolled the residential houses each night before dawn, shutting windows to conserve fuel (sleeping in fresh air was at that time considered a requisite of healthy living), and volunteers dug potatoes at local farms, thus giving shape to the war effort in a way the college president’s assurance that the “study of liberal arts was a promise to the world that peace would return” did not.

Assigned to Park House, a rambling old mansion where forty-five young women lived under the eagle eye of one Miss Atossa Herring, Joan quickly formed two fast friendships. With Martha Burke (now Martha Bertolette), from Plainfield, New Jersey, she indulged in talkfests lasting into the small hours, when they would drift into the john so their roommates could sleep while they rattled on. An intent listener, Joan put questions to Mopse—as Joan dubbed her—like nobody else’s: “What does your father really think of your mother?” “How do your brothers feel about sex?” Joan’s other best friend was Joanne Witmer (today Joanne Von Blon), called Wit, a Minneapolis native from a privileged background. They too talked incessantly, taking long “wallowing walks” in the course of which Joanne discovered “a wonderful friend, the kind of friend you dream of, very emotionally available, very open.”

Others at Park House found Joan inconsiderate, hard-nosed, or unkind. They disapproved of her cruel dig at a certain southern student with large rubbery lips—“Can you imagine kissing her? It would be like kissing a wet toilet seat!”—and her careless rich girl’s acts like taking other people’s bicycles without asking and bumming cigarettes but never repaying. Her language (“Well, did you fuck him?”) shocked some; her intellectual snobbery rankled others. Once two housemates turned the tables on Joan by talking up imaginary books, then calling her bluff when she claimed to have read them. Mopse observed that her friend was less self-confident than she pretended to be.

An English major (Smith did not then offer a major in art), Joan was bright and defiant enough to use her grades as evaluations of her professors, as much as the other way around, turning in stellar performances for only those she respected. She pulled a C in psychology because she took a dim view of the instructor’s approach and later earned another C, from a geology teacher for whom she had little but scorn.

The exception was an assignment in the figure-drawing class she took freshman year from artist and art historian Priscilla Van der Poel. Joan plugged away at her drawing, yet (according to Martha Bertolette, who was in the same class) “didn’t really know what a line was.” “I hit it just right,” Martha remembers of her own drawing, which earned an A–while Joan’s came back with a B+. Joan long obsessed on those two grades. “Joan!” Martha insisted. “You know it was just a mistake!” In 1986 art historian Linda Nochlin conducted an oral history interview of Joan for the Archives of American Art. “Is there anything particularly important about Smith?” inquired Nochlin. “I mean, anything important that you think took place that might be relevant to your later career?” “Well, I got a B+ in art,” the painter deadpanned.

At Smith, Joan lived by her own code of embattled idealism, sly defiance of authority, and loyalty to friends. In the words of Joanne Van Blon, Joan’s “sense of justice and her sense of integrity and her sense of truth were monumental.” So too was her generosity. After Wit spoke of her love of Milton, a leather-bound, gold-leaf-trimmed edition of The Poetical Works of John Milton appeared on her bed, thoughtfully shoplifted by Joan at the Hampshire Bookshop. Joan could easily have afforded the book, but not only was pilfering daring and fun, it was also gratifying to the resentful daughter in her, who was not at all sure she wanted to be at Smith. With this, as with other acts, she said: My parents made me be here, they asked for it. As for the college, acting in loco parentis, Joan did as she pleased but made sure they never got anything on her. When she royally violated curfew one weeknight, straggling in from a date at two thirty a.m., she contested the demerit with the cleverly fabricated story that she had been visiting a poet friend of her mother’s who was teaching at Amherst and she could not possibly have slighted the distinguished bard by leaving in time to meet the ten p.m. curfew. Moreover, she demanded that Mopse back her up with a lie.

A date was something of an event during those war years, when Saturday nights found many Smithies catching a movie together or tossing back a few beers at Rahar’s, the local joint, and bemoaning the chronic shortage of “man-power.” The issue went beyond dateless weekends, for even at a top academic institution like Smith, many women were fundamentally in the business of finding Mr. Right. Preparing for a career was less a matter of making one’s mark in the world than of establishing a holding pattern: the real future began with a wedding to the guy whose name one took, whose children one bore, whose household one managed, and whose way of life one assumed.

Though Joan did not rule out marriage, she already knew that traditional domesticity wasn’t for her because it could derail a female artist’s career. She might marry, but she would never be a wife. When Joanne, an aspiring writer, got a diamond solitaire engagement ring from her Amherst boyfriend, Phil, Joan appeared in her friend’s room wielding scissors, grabbed a clump of her hair, and hacked it off. This gesture oddly recalls French townspeople’s later head shaving of women who consorted with the Nazis, an act of public humiliation inflicted upon the tresses that represent their seductive powers. Ah, you don’t subscribe to my view after all, Joan seemed to say. You’ve betrayed me. You’re really one of them.

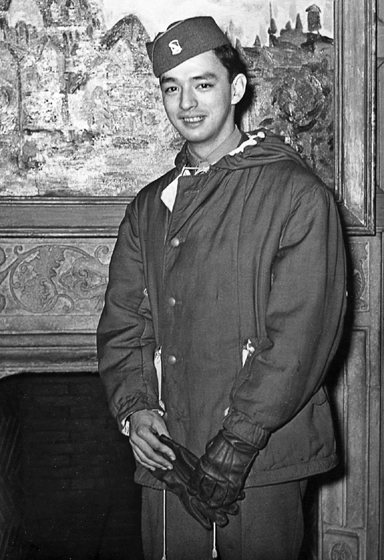

Joan, age twenty-one, insisted she was not beautiful, c. 1946. (Illustration credit 4.2)

Not that Joan didn’t adore men. With her splendid 124-pound body, full breasts, caramel coloring, Lauren-Bacall-as-Slim-Browning hairdo, little nose, and intriguing half smile, she exuded a young, smoky, tough-cookie glamour. Her uniform in those days was a double-breasted trench coat over a plaid flannel shirt and dungarees rolled to the knees, but on special occasions she donned a boxy, well-tailored suit and her one precious pair of silk stockings, a gift from Sally, and looked “sexy as hell.”

Letters between the two sisters (Sally remained at Sarah Lawrence) dished “dirt with a capital D”: gossip and tales of the pleasures and terrors of marginal virginity. A certain Dick had drugged Sally with four bourbons, then drove her to a lover’s lane, and “before I knew what was happening, he had my bra undone and my panties off … BE SURE TO TEAR THIS UP.” (Joan did not.) “M.L.” (the sisters coded men’s names in case their letters fell into parental hands) was a “complete wreck” over Joan. Sally meanwhile was “plodding forth” with “a sex-starved veteran of the Sicilian campaign—cousin of a Marine who tried to lay me about four weeks ago.” Joan had finally let Dickie Moore kiss her: “not bad but I’m afraid he’s undersexed.” And one of the Hughes boys, their perennial double dates in Chicago, still had “chronic hot-pants” for Sally. After some incident during one of Joan’s breaks, Mr. Hughes Senior had vigorously complained to Marion that Joan was a bad influence on his sons. Sally got mad that “Mr. H.” would “dare say you are leading those dumb sots of sons astray,” while Joan reacted by writing “Mr. H.” a wickedly sarcastic letter that had Sally both scolding her for bad breeding and admiring her “super duper job.”

Both sisters played the man game enthusiastically, but unlike Sally—who wanted a husband, children, a big house, the works—Joan was not playing for keeps. She wisely chided Sally for running her love life like a factory:

What’s your hurry—you drop one man and expect another to move up on the assembly line—one’s love life is hardly a modern mechanized thing—and hell—having a man is an artificial stimulus—a little like taking dope—perhaps to appreciate the dope you should go without it—I know I’m no example—but you can find what you like in one man in many people—men and women … A man is nice to lean upon—good for the vanity but most of what’s going to make you happy is inside you … You’ve got to be strong, S.—let things come to you—you’ve got to decide what to you is valuable—what will make you happy (and not kid yourself into thinking another person will do it) and when you alone have more self-confidence, only then is it safe to lean on someone else … There’s a lot to be enthusiastic about, S.—if you look for it—qualities in people (not the whole person)—qualities in things—that you can discriminate—like walking through a garden—just picking certain flowers.

Back in Chicago that June, Joan began dating the older brother of her ex-classmate Lucia Hathaway. A student leader and enthusiastic actor at Parker (his famous line: “It’s this beastly neuralgia”), Bullock Hathaway loved to hold forth on subjects ranging from the Oedipus complex to Hamlet to democracy. A recent cum laude graduate of Harvard in the accelerated program and one of those outstanding young people who incarnate the best hopes of a generation, Bullock was destined for a career in politics and law. He was dark, handsome, charming, and, according to Mopse (who visited her friend in Chicago that June), “crazy about Joan.” But, by early July, Bullock had departed for basic training on Parris Island, and Joan for the Ox-Bow Summer School of Painting near Saugatuck, Michigan.

Founded as an artists’ haven in 1910, Ox-Bow lay at the end of a dirt trail through a fragrant dark birch and pine forest on Lake Michigan’s eastern shore. Named for a bygone loop of the Kalamazoo River, the school occupied an assortment of rustic, sun-bleached, unelectrified cabins, plus the old Ox-Bow Inn, haunted by memories of lumber barons and captains of the Great Lake steamers. Burr oaks, some encircling an ancient Pottawattamie mound, dotted its sand dunes where people played volleyball and, after dark, built bonfires and gazed up at a million stars. Ox-Bow was sweet-smelling and drowsy and Hopperesque and wild.

Joan took three classes that summer. The first, a morning class in figure painting, was taught by Robert von Neumann, a German émigré via Milwaukee who had lost a leg in World War I. A loosely expressionistic artist, von Neumann pushed no particular agenda but rather took student work-in-progress for what it was, critiquing it in a humane, encouraging way. Their easels set up in a field of blond grasses skirted with resinous blue green woods, von Neumann’s students painted nude models perched on old kitchen chairs. Joan loved doing outdoor nudes, so odd and exciting, especially when the model was Cleo, with her marvelous soft, round body as if from a Renoir—“really Frenchy.” In the afternoon, Joan took landscape painting from the perennial Malcolm Hackett, and, in the evening, she learned lithography by kerosene lamp.

She found von Neumann particularly genial and inspirational. He spoke to his students about decisions. A faraway look in her globular eyes, Joan listened intently, distractedly flicking her cigarette in the direction of the little bucket she carried around as an ashtray. During the war years, you improvised your life. If the world is sliding out from under you, Joan felt, it’s time to quicken your steps. Bracing for a storm at home, she resolved to transfer to Chicago’s School of the Art Institute, where von Neumann taught—a scary but necessary decision, she felt. “My decision to leave college was the decision that time is short,” she later explained. “Time to become a painter. I felt one doesn’t paint by being an English major. One paints by painting. Full time.”

Back at Smith nonetheless for her sophomore year while she negotiated with her parents, Joan watched Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo create a forty-foot fresco for the art library and took drawing and painting from George H. Cohen, who, to her amusement, stole a kiss at their first meeting. Finding Cohen a mediocre artist and teacher, however, she preferred to work on her own. “J-child,” purred Sally, “you are painting so well.”

That Thanksgiving, newly commissioned Marine Corps Second Lieutenant Bullock Hathaway visited her in Northampton. Then Christmas came and went. She had a small show at Parker. Spring brought watercoloring under Smith’s apple trees and sketching along the grassy banks of Paradise Pond and Mill River. Said Joan, “I’d always go further than Paradise Pond … I always wanted more.” Yet, stopped dead in her tracks for several weeks that spring by one of the deep depressions that would plague her adult life, she wanted nothing at all for a time.

During her final semester at Smith, Joan studied English literature with Dr. Helen Randall, the last of the trio of teachers who profoundly affected her. Randall specialized in Romantic poetry—Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, Byron, and Browning—writing that touched her soul even as she applied the highest standards of scholarship to its analysis. Her student and later colleague Margaret Shook describes Randall as “the first teacher I had ever encountered whose intense love of poetry was equaled by her intellectual power. She had an intricate mind, awake to contradictions, paradox, and irony. She seemed to speak in paragraphs rather than sentences, and often these paragraphs took the form of a contradiction: ‘on the one hand …; on the other hand.’ ”

Thus, in her lectures on Wordsworth, with whose poetry Joan promptly fell in love, Randall would have distinguished between, on the one hand, the vigorous rebel of the Lyrical Ballads, a poet of ordinary but specific and intensely felt moments, and, on the other, the (in the words of writer Margaret Drabble) “lover of Nature, friend to butterflies, bees and little daisies, in fact a sentimental tedious old bore.” (Joan too detested shopworn pastoralism: “I hate the word ‘nature’ as it is used in the bird-watching sense.”)

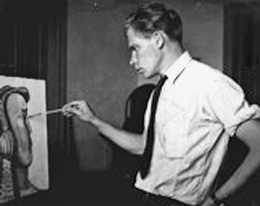

Joan with fellow student Dan Sparling at Ox-Bow, 1943 or 1944 (Illustration credit 4.3)

Seeking to communicate her approach to painting, Joan would later use an analogy with lyric poetry, famously defined by Wordsworth as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” Such feelings, he writes in The Prelude, leap from the sky, hills, caves, and trees that make “The surface of the universal earth, / With triumph and delight, and hope and fear, / Work like a sea.” For Joan, too, landscape was vital: her Lake Michigan was not “a dull body of water,” but rather “changing, alive,” as Wordsworth’s earth was “not a dead cinder turning aimlessly in time, but a living, moving, feeling thing.” A Mitchell painting—the 1991 L’Arbre de Phyllis, for instance, which involves feelings inseparable from a certain November-yellow gingko tree standing in a certain village in France, a tree once loved by a certain Phyllis—is as firmly rooted in time and place as is Wordsworth’s “The Daffodils,” with its wind-combed blossoms discovered by the poet and his sister on a March walk in Townend, Grasmere. At their best, both painter and poet—herein lies an important ingredient in their greatness—retain not conventionalized memories neatly fitting the preset schematics of adult experience but rather something closer to the unwieldy and unnamable raw material of life. Psychoanalyst Ernest G. Schachtel writes of how “adult memory reflects life as a road with occasional signposts and milestones rather than as the landscape through which this road has led,” meaning that adults recollect the events the world deems important and then not so much the events themselves as the fact that the events took place. Wordsworth and Mitchell, on the other hand, body forth what Schachtel calls “a vision given only to the most sensitive and differentiated mind as the rare grace of a fortunate moment.”

Moreover, a Mitchell canvas takes as its subject not nature, but rather the artist’s felt memories of nature, an approach which (as several critics have pointed out) parallels Wordsworth’s use of “emotion recollected in tranquillity.” The poet draws from remembered sensations in “Tintern Abbey,” for instance, and, most memorably, in “The Daffodils”:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

“They flash upon that inward eye / Which is the bliss of solitude”—as if Wordsworth, like Mitchell, treasured up moments of visual splendor to be pulled out when life brought scant pleasure and anxieties crowded the mind.

As that semester continued, “Randall’s Romantics” yielded to Victorian poets, and they to essayists and novelists including, incongruously, Tolstoy, whose War and Peace had been patched into the syllabus of every English II class in recognition of the times. In her term paper for Dr. Randall, Joan examined Tolstoy’s epic through the lens of his 1896 essay What Is Art? The result—a tight, even, four-thousand-word braid of handwriting (like boys in those days, Joan never bothered to learn typing, smug in the knowledge she would never need to be a secretary)—is remarkable. Though ill at ease with abstract reasoning and conceptual language, she conceived of such assignments as compulsory “mental gymnastics” and badgered herself into excellence. Her attitude: Why do it if you’re not going to do it well? Any dope can write a C paper. It doesn’t stand for anything. Besides, she deeply respected Helen Randall and thus gave her all.

Joan begins her paper by recapitulating Tolstoy’s attacks on formalism on grounds that art for pleasure’s sake, as favored by the upper class, subverts art’s rightful purpose, which is to transmit feelings. The better (i.e., the more morally uplifting) the feelings, Tolstoy continues, the more readily they are conveyed to the viewer, and thus the better the work of art. The pure and infectious feelings of songs sung by peasant women, for instance, make them superior to Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in A Major, op. 101. No art at all is preferable to art that fails to advance the brotherhood of man through shared feelings. Bad art should rightfully be destroyed.

Joan counters that, because art builds upon what has come before, Tolstoy’s assumption of the existence of an ultimate criterion for art is flawed. She accuses the Russian of a narrow, dogmatic response to a complex set of circumstances: if Tolstoy pins his faith on morally uplifting art, so be it, but others should not be compelled to follow suit as he, a firm believer in freedom, should recognize. Furthermore, argues Joan, Tolstoy essentializes the classes, demonizing the aristocracy and idealizing the peasantry. She concludes by lauding War and Peace (which antedates What Is Art? by nearly thirty years) for conjuring rather than preaching about the human condition, recognizing that human actions (if not human nature) can improve, and balancing moral considerations with the complexities of life.

With her Tolstoy paper, Joan mapped out her lifelong position that an artist must command the freedom to set the terms of her art: “There is no one way to paint. There can’t be. There is no one answer.” Nor, she believed, is there any morality in making a picture: either it works, or it doesn’t. Prodded by one interviewer, years later, to pronounce on whether artists should take a political stance in their work, she responded, “I don’t think there’s any shoulds.” The interviewer kept fishing: “You don’t like work that tells you what to think as opposed to work—.” Joan finished: “that allows you to feel.” Mitchell and Tolstoy’s shared preoccupation with feelings appears to establish a mutuality between the artist and the writer; for the Russian, however, the feelings in a work of art need not be powerful but must be infectious. Joan, on the other hand, took for granted that only the very few who really care about painting will engage with her work at a deep level. In that sense, she was an elitist.

“This is a superb analysis,” Dr. Randall comments at the bottom of Joan’s essay, “… for straight and vigorous critical thinking in a college paper … one could hardly ask for anything better. A.”

Having made a point of getting to know her teacher, Joan received a rare invitation to tea at the farmhouse where this shy but intrepid Vermonter, a poodle her sole companion, competently met the challenges of rural New England life. Little did the young painter know that she was glimpsing her own future years in the country, off the power grid of the art world.

Back at Ox-Bow that summer, Joan one morning found herself painting next to Zuka Omalev, née Booyakovitch, the daughter of escapees from the Russian Revolution, a fine arts major at the University of Southern California, and the young wife of All-American basketball player Alex Omalev. Joan sized up Zuka’s dark mane, Modigliani look, and likeable manner and, after class, inquired, “Do you want to go for a swim?” The two slipped into their bathing suits, Joan’s a beige tank suit and Zuka’s a two-piece powder blue number with a little skirt. (Her hometown was Hollywood, California.) But Joan forgave her. When they got to the beach, Zuka remembers, “Joan went psssst! She dived in, swam I don’t know how many yards out, turned around, swam back. She was a terrific swimmer. And she was out! That was it.” Zuka, meanwhile, splashed around, swam a bit, and splashed around some more, and Joan forgave that too.

Still feeling the spell of War and Peace and assuming that “Russian” was shorthand for “soulful,” Joan latched onto Zuka’s Russianness. As an antidote to her own family’s cold, stoic midwesternness, she played with a pseudo-Russianness of her own that led her (and two or three others that summer) to throw paint at their canvases and sound off about how only the act of painting counted.

Along the same lines, New York artist Jane Wilson recalls hearing in the early 1950s about a certain

little dinner with painters and friends and so on. And there was a great deal of drinking, and it got exceedingly nasty. And there was yelling and there was screaming and there was carrying on. Between Joan and almost everybody. And finally people got tired and went home. And the person at whose house this took place thought that this was a disaster. Never again! This is the worst thing that has ever happened. I can’t imagine how this came about, but I’ll never do it again. Then Joan called her up and said, “What a wonderful Russian evening!”

In contrast with the Joan of 1951, the Joan of 1944 demonstrated a classy reserve—“very Anglo-Saxon and keep a stiff upper lip and you don’t complain and that kind of thing”—that Zuka, in turn, romanticized. The forceful personality that led Joan to insist, for instance, upon teaching Zuka how to make a bed properly, a skill she herself had acquired only recently at Smith, also fed Zuka’s fascination with her new friend. However, the Californian soon tasted Joan’s arrogance and ruthless competitiveness. One night mischief-makers crept into their painting studio and mixed up the easels, normally kept at the very same spots over the several days of a pose. Arriving early, as usual, the next morning and seeing what had happened, Joan grabbed an easel, scribbled her name on it, positioned it, and started painting. Later a middle-aged classmate entered and said, “That’s my easel.” Joan replied, “My name is on it. This is my easel.” When the man protested, she stonewalled him. Zuka mentally gasped, “Oh, my God! This is terrible!” But Joan had the easel. So what if it was his? Fuck him. She was working. She showed no inclination to negotiate, no twinge of understanding, no feeling of remorse.

That summer was notable too for Joan’s bloodless decision that it was time to have sex. Scouting around for a partner, she chose twenty-six-year-old painter and assistant teacher Richard Bowman. The son of a courthouse employee and a housewife from Rockford, Illinois, Dick had graduated from the School of the Art Institute in 1942 having won one of four coveted traveling fellowships the school awarded in the belief that a first-rate art education must be crowned by a sojourn abroad. Bowman had spent his in Mexico, where he stayed for a time in Michoacán with painter Gordon Onslow Ford and his writer wife, Jacqueline Johnson. There primal volcanic landscapes and pellucid skies had unveiled to him “a vision of nature as energy.” Pierced by the realization that, their apparent stability notwithstanding, rock formations pulsate with movement and light, Dick had made beautiful drawings, then swung into a long series of paintings in which skies throb with color, and matter and energy interpenetrate. Intuiting kinetic theory, he titled the pictures Rock in Motion or Tense Form or Dynamic Tension and, collectively, the Rock and Sun series.

A husky outdoorsman squarish of shoulders and face, Dick hid his shyness under cocksure masculinity. His nickname, Rocky, alluded to the Mexican work but also suited his vaguely pugilistic manner. At first glance, Bowman seems an odd, too-provincial choice for Joan, yet his marvelous canvases, up-and-coming career (he was a protégé of Art Institute director Daniel Catton Rich), and eagerness to help Joan with her work (he advised that she “get good and clean color” and “penetrate reality but abstract it”) met her needs. As for Dick, Joan’s big-shot family and assertive manner impressed him. Like a smitten schoolboy, he carried her paint box. And the physical attraction between the two was palpable.

Come Labor Day, Ox-Bow closed its doors, and silence once again settled over the rustic cottages soaking in Indian summer sun. On one wall of the so-called White House had appeared a scrawled message that was to survive for years to come: “Joan, will you marry me?”

Dick Bowman, Joan’s first lover, painting in Mexico, 1942 or 1943 (Illustration credit 4.4)

Four months after shipping out to join the 8th Marine Gun Battalion on Guadalcanal, Bullock Hathaway had taken part in the perilous invasion of Peleliu Island, where eight thousand Japanese occupiers met the Americans with punishing fire. Two weeks later, the young officer volunteered to accompany a detail of machine gunners supporting an artillery unit’s attack on the island’s heavily fortified caves. His men facing fierce resistance as they searched out enemy targets, Bullock courageously laid himself open to danger as he directed counterfire until he was killed by a sharpshooter’s bullet.

Bullock Hathaway’s death on September 30, 1944, on that remote strip of hot coral sand threw many into profound grief. Some of his professors wept at the news. Joan was devastated. She phoned Martha, “really broken up, just hating the fact that he wasn’t coming back,” and carried away by her razor-sharp pain: “But I was engaged to him! But I was going to marry him!” Bullock’s was her first important death.

In describing Joan, her friends often bring up her primal terror of death and dying, her anguish at the thought of light extinguished. For her, forgetting the horrid finality of not being alive was ultimately what painting was all about.