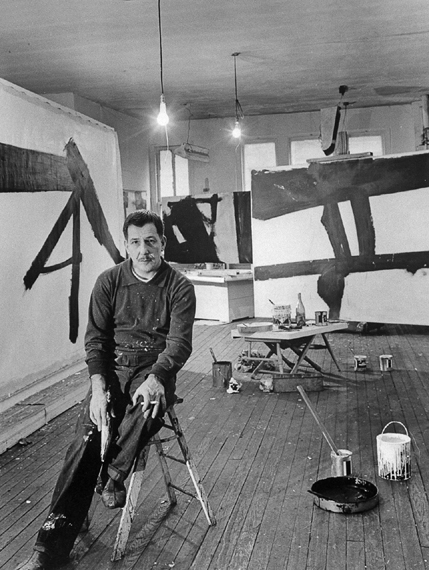

Painter FRANZ KLINE

about a downtown New York loft

building with a storefront and an

enormous neon sign

In late March 1950 readers of Life magazine opened to a ten-page cover story hailing Howard Warshaw, Aleta Cornelius, Franklin Boggs, Honoré Sharrer, and fifteen other painters—Buffalo, Jersey City, and Beloit were all represented—as the nation’s best under age thirty-six. These young artists’ sentiment-laced scenes of candy stores, carnivals, slums, Chinese swans, and automobile graveyards in retooled versions of traditional modes had earned Life’s kudos for their felicitous sureness of style. Millions saw the work. In contrast, the handful of New Yorkers who ventured into Talent 1950, curated by critic Clement Greenberg and art historian Meyer Schapiro for the Samuel Kootz Gallery that same spring, found the slatherings of twenty-three young artists who had rejected standard answers to the question “How should one make a painting?” and had stripped their work of finesse. Grace Hartigan, Esteban Vicente, Elaine de Kooning, Franz Kline, Alfred Leslie, and the others searchingly mixed it up with raw pigment. Shunned by galleries (the result of a cancelation, Talent 1950 was a first), collectors (nothing sold), and critics (more or less mute), these fiercely ambitious upstarts made art not for the indifferent or eye-rolling readers of middlebrow magazines but for each other and for History. Indeed, they derived a certain artistic freedom from knowing that nobody wanted it: “Well, we don’t sell anyway, so why not?”

That same spring, the Metropolitan Museum presented an expanded version of Life’s “19 Young Americans.” “Timid practitioners of various sorts of anecdotal romanticism,” scoffed the devastatingly articulate Thomas B. Hess, managing editor of ArtNews, one of the young progressives’ few allies. Moreover, the Met had recently announced a regional jurying system for its new competition for painters, thus guaranteeing conservative choices. At stake was prize money as well as inclusion in an important upcoming survey of American painting. Outraged, older progressive artists responded with a letter of protest in the Times. Fifteen of them were subsequently photographed by Life, which dubbed these stern-looking veterans—fourteen men and one woman—“the Irascibles.”

The one in the middle, Jackson Pollock, had already earned notoriety for his wildly unorthodox drip paintings, thanks to an earlier Life feature (“Jackson Pollock: Is He the Greatest Living Painter in the United States?”) which had simultaneously patronized him as a paint-drooler and celebrified him as a brooding jeans-wearing, cigarette-dangling-from-the-lips Brando. Pollock’s next opening, at Betty Parsons’s Fifty-seventh Street gallery on November 21, 1949, had brought a bolt out of the blue: besides the usual studio rats and smattering of critics, a well-heeled uptown crowd occupied Parsons’s attractive white space. “What’s going on here?” a startled Milton Resnick turned to his fellow painter, Willem de Kooning, after observing these strangers “going around shaking hands.” “Look around,” de Kooning famously replied. “These are the big shots. Jackson has broken the ice.” Eighteen Pollocks sold.

Not long thereafter, the Museum of Modern Art’s powerful director of collections, Alfred Barr, selected vanguard painters Pollock, de Kooning, and the late Arshile Gorky as three of the six artists for the contemporary section of the U.S. Pavilion at the 1950 Venice Biennale. Barely dry at the Biennale, de Kooning’s Excavation would then travel to the Art Institute of Chicago, where it was crowned with a $4,000 prize and purchased.

Was 1950 a fulcrum year after all? Sculptor Philip Pavia had prophesied as much at the downtown artists’ New Year’s Eve bash: “The first half of the century belonged to Paris. The next half century will be ours.”

Nowhere else on earth was painting lived as intensely as below Fourteenth Street, where, after every night of beery camaraderie, painters still had to face the decrepit walk-ups and the scramble to make rent. Many lived along East Ninth Street, near Wanamaker’s department store, or East Tenth, especially between Third and Fourth Avenues, a block dreary with a metal stamping factory, an employment agency for “bums,” and a wino bar or two. Unheated except for gas or kerosene stoves, their naked-light-bulb apartments or illegal-for-habitation lofts went for only thirty or forty dollars a month, but even that was a stretch. Then there were the bills at Rosenthal, for canvas, brushes, jumbo tubes of Bocour oils, and whatever else they couldn’t beg, borrow, steal, improvise, or get wholesale. An old incorruptible who had long since chosen art and poverty over compromise and solvency, Bill de Kooning once walked home forty blocks from a museum appointment rather than spend a nickel for the subway. Grace Hartigan, who was raising a young son alone, stocked her window-ledge larder with bruised fruit and day-old bread. Almost everyone took odd jobs.

Making a virtue of rough-edged living (as opposed to the self-conscious bohemianism of the Village or the middle-class lifestyles of advanced artists uptown), the downtown crowd survived on coffee, cigarettes, beer, and talk, venting the tension and solitude of painting by gathering on stoops, at bars, and in all-night cafeterias, chop suey joints, and cheap Italian places, where they washed down seventy-five-cent plates of spaghetti “with green sauce” with ten-cent glasses of Chianti.

Their mutuality—the life, good and bad—outweighed all else. “You couldn’t be an artist in the middle of Ohio,” as Pavia put it. “You’d isolate yourself too much. You really needed someone to kick you.” As for the “toughness and pressure of neglect” by the art establishment, it had resulted, Tom Hess observed of the younger contingent, in “a group that seems as blithe and as debonair as were the bohemians of the Impressionists’ Café Guerbois.”

As time went on, the downtown artists talked about having a place of their own, so they could be among themselves to chew over their artmaking as the old-timers among them had once chewed over Picasso’s, a place more congenial than the Waldorf, where, for years, they had been staking out tables and nursing nickel cups of joe loaded with sugar and milk. Thus when a cheap vacant loft materialized at 39 East Eighth Street, around the corner from their favorite bar, the Cedar, a nucleus of artists met, decided, scared up the $250 deposit, and set about putting the space to rights. At the end of that year the Eighth Street Club opened to “no manifestoes, no exhibitions, no pictures on the walls,” just keys for its charter members and informal gatherings arranged by jungle telephone. Not until Pavia started organizing Friday-evening lectures and panels, however, did the Club emerge as a vital meeting place for downtown artists and uptown intellectuals, a conduit for their prodigious social energies, a heady land’s end.

The oldest among them could trace their attitude of collective struggle back to the 1930s, when the Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration had lured them out of their studios. By decade’s end, a number had organized against the antimodernist regionalism typified by Grant Wood as well as the social realism identified with artists like Reginald Marsh and the Soyer brothers. Painter Lee Krasner, for one, had begun working in an apolitical nonrepresentational style, as championed by the American Abstract Artists, while Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, and others had formed The Ten to search for ways to conjugate social consciousness with abstraction.

Then World War II had sent into history the best years of the School of Paris and brought to New York leading European modernists including Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall, Salvador Dalí, Fernand Léger, Yves Tanguy, André Masson, Max Ernst, and Roberto Matta. Though distanced from the New Yorkers by language and attitudes, the Europeans had deeply impressed locals with their unfailing bohemian élan and native faith in the vital meaningfulness of art. And, while the American avant-garde had little use for the formally retardaire Surrealist style exemplified by Dalí, painters like Arshile Gorky and Jackson Pollock began taking cues from the abstract Surrealism of Matta, whose automatism seemed to unwrap the latent content of the individual psyche.

By war’s end, the most self-confident American artists were dismissing the refinements of Continental painting, some even considering Cubism (once revolutionary for its overthrow of Renaissance space) to be a still-useful but concept-driven academicism that clipped one’s risk-taking wings. Rothko and Barnett Newman—the former with luminescent fields of color, the latter with meticulous calibrations of scale, proportion, and hue—would soon dare the elimination of all that stood between the artist, the viewer, and the sublime. No longer would they paint experiences: their pictures would be experiences in the viewer’s own space. Meanwhile, de Kooning and Pollock were engaging in what painter John Ferren termed “searching itself as a way of art,” de Kooning shuttling back and forth between abstraction and representation as he laid out on canvas his struggle and self-doubt, Pollock transforming the act of painting into an experience of self-realization: the artist as hero in the badlands of modern life.

Such bold experimentation took shape against a backdrop of military victory and triumphant Americanism, shadowed, however, by knowledge of the moral failure of all absolutes during the war. The early 1950s brought the displacement of national purpose by shallow materialism as well as Cold War paranoia and threat of nuclear holocaust. With the world teetering on the brink of annihilation, politics as usual felt irrelevant. Anxiety worked itself deep into the American psyche, and, as many artists saw it, abstract painting became the paradigmatic vehicle for self-discovery and manifestation of the zeitgeist. Akin to psychoanalysis in its preoccupation with process, instinct, free association, and the unconscious, the new art proclaimed existentialist attitudes. Its younger practitioners, however, refugees from the “silent generation,” would turn their backs on despair, the better to confront self-created freedom through the act.

Notwithstanding the heterogeneity of this new art, painters Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt organized a three-day artists’ symposium in April 1950 to address, in part, the issue of packaging its attitudes and practices. The only non-artist in attendance, MoMA’s Alfred Barr (who believed that every work of art is assignable to its rightful place in a flowchart of historical progression) pressed the others to choose a name for their movement or direction. But they dragged their feet. Why falsely imply that an ethos of volatility and possibility, an attitude of adventurous searching, constituted a unified body of work? De Kooning responded, “It is disastrous to name ourselves.” Yet Motherwell’s term based in geography—“the New York School”—took hold, as would the process-oriented term “action painting” and the stylistically focused “Abstract Expressionism.”

In the fall of 1949, Mr. and Mrs. Barnet Rosset Jr., only vaguely aware of recent developments in New York painting, debarked in Manhattan. Following a short stay at the Chelsea Hotel and a Christmas visit to Chicago, they rented a vintage artist’s studio behind a brownstone at 267 West Eleventh Street. With its wide-planked floors, fireplace, skylight, and miniature garden, this charming dollhouse, no bigger than twenty by twenty (plus a semifinished basement), put Joan’s painting literally at the center of their lives.

In early January 1950, two months before Life’s touting of “19 Young Americans,” Joan made overtures to a few New York galleries, of which there were then about thirty, and was promptly rejected. Dealer Julius Carlebach, for one, told her, “Gee, Joan, if only you were French and male and dead.” So she retreated, not unhappily, to her “ivory tower,” where she continued to flog semiabstract scenes in a shallow pictorial space.

French subjects had quickly given way to New York–based fare: Coney Island, Subway, The Bridge, and The City. Jazzed with the urban energies of Gotham at dusk, yet stiffly controlled, The City is a paean to New York, Cubist city par excellence. Windows and assorted details identify its rigging of rectangles, triangles, circles, and arcs as buildings, bridges, streetlights, and signs, while the whorled beams of a Great White Way at its activated center entangle themselves in orthogonal form. The artist’s concern with pictorial dynamics converges with her attention to light (solar, tungsten, neon), light depicted, rather than felt.

Two less successful oils from this very early New York period—which Joan later described as “horrible”—all but demand psychobiographical readings. One (all grays relieved by bits of white, ochre, and blue) represents a row of windows, their lower panes inlaid in a rote pattern that vaguely evokes Cubism as a tired, codified art-making practice. Presumably Joan intended a view of Manhattan’s spatial jumble, yet one can’t help but read up-against-the-wall frustration. The other, Figure and the City, is surely the weirdest painting of Mitchell’s career. Here, against a backdrop of jittering jigsaw geometry, a faceless young woman turns from the breakaway shapes that descend upon her as if to swallow her up. Was the idea to capture on canvas her experience of boundarylessness? Encased in thick, dark lines, the figure’s impossibly thin arms go on forever, while her head and shoulders meld with the geometric forms. On a pictorial level, stylized figuration and post-Cubism unhappily cohabit. As she pushed through this failed attempt at a more subjective kind of art, Joan knew that she would never again paint the human form. But what now?

Joan, twenty-six, and Jimmie with Figure and the City, around the time she turned to abstraction, thinking that her father “couldn’t even criticize what it was, you know?” c. 1951 (Illustration credit 6.1)

One day later that January, Joan walked into the Annual of American Painting at the Whitney Museum (then on West Eighth Street) and, in the very first gallery, stopped dead in her tracks. Muscular, unruly, and ambiguous, Willem de Kooning’s six-foot-nine-inch-wide Attic ramped up before her. Black lines knifed through its shallow whites, forming vaguely anatomical, vaguely cartoony fragments—heads, orifices, spiky limbs akimbo—that tightened into each other as they darted to oblivion and back. Smudged with red, these elusive forms bore ghost images of the newspaper with which the artist had covered the wet pigment between painting sessions, thus heightening the effect of random information and foregrounding the material facts of Attic’s making. Moreover, its snaggly lines, zonked energies, and refusal to hold form made Attic a quintessential painting for the age of anxiety. It also lived up to its title. Abstraction, by de Kooning’s lights, was not a way of “taking things out or reducing painting” but rather a way of “putting more and more things in it: drama, anger, pain, love, a figure, a horse, my ideas about space.”

Joan had never heard of Willem de Kooning, but, in the days that followed, she went looking for him. In fact, he lived only five minutes away, on Fourth Avenue across from Grace Church School. But she was somehow directed instead to the Ninth Street digs of painter Franz Kline. After climbing three flights of worn stairs one evening, she knocked on Kline’s battered door. The sight that met her eyes when he opened it struck another tremendous blow. In the cluttered studio, separated from his living quarters by a half wall the painter had built, hung several large, bold, stark unstretched canvases, among them perhaps the artist’s masterworks from that period: Hoboken, Nijinsky, Cardinal, and Chief. Built from black and white brushstrokes that braced, clobbered, sideswiped, clinched, and/or slammed into each other, Kline’s abstractions manifested a powerful materiality, evoking, at times, steel bridges, railroad trestles, and urban scaffoldings.

The quintessential action painter, Kline would begin by sliding a wide housepainter’s brush into a big can of glistening housepainter’s enamel. Fixing his gaze on a spot at the far end of his five- or six-foot-wide canvas, he would then crouch, spring, land, and race on, dragging and twisting his paint-juicy brush across the gessoed linen field. Later he worked the edges of his strokes: white on black, black on white. As much drawing as painting, as much act as drawing, Kline’s big oils immediately had Joan climbing the high ropes of art. And the gouache and ink sketches done on the pages of telephone books (he loved their gray sidewalk look) that littered his floor impressed her as “the most beautiful things I’d ever seen in my life.”

Franz Kline in his studio, 1954 (Illustration credit 6.2)

If the art wowed Joan, so did the man, the prototype, she felt, of the “seedy, exciting” New York painter up against the world. Not that Kline looked arty. No New York School painter did. His natty mustache, Ronald Colman face (an Anglophile, Kline adored Colman), and black snap-brim fedora could no doubt pass at the Rotary Club in his birthplace, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, but the doleful eyes and the widow’s peak that made of his face a lumpy heart set him apart. So did the irresistibly ebullient, wisecracking loop-de-loop barfly talk that kept Joan at Kline’s studio until seven thirty the next morning. Poet Frank O’Hara once made a valiant attempt at capturing the painter’s cataract of words:

Which reminds me of Boston, for some reason. You know I studied there for a while and once I was up there for a show and met this Bostonian who thought I looked pretty Bohemian. His definition of a Bohemian artist was someone who could live where animals would die. He also talked a lot about the 8th Street Club and said that Hans Hofmann and Clem Greenberg run it, which is like Ruskin saying that Rowlandson and Daumier used up enough copper to clad the British Navy and it’s too bad they didn’t sink it.

Raised in a railroad town in the Lehigh Valley—coal country—Franz Kline had captained his high school varsity football team. After two years at Boston University and three at the Heatherley School of Fine Art in London, he had moved to New York and married his British sweetheart, dancer Elizabeth Parsons. Living in grim cold-water flats from which they were more than once evicted because they couldn’t make the rent, the couple barely scraped by. In 1946, Elizabeth’s mental illness reached the point where Franz could no longer care for her, and she was committed to a state hospital on Long Island. Nor had Kline earned the unqualified respect of his colleagues. Some considered him a loser for having traveled the route of illustration (he had started as a cartoonist and eked out a living peddling at street fairs and doing murals in bars) rather than that of Cubism and the WPA, and for painting sentimentalized pictures like rocking chairs and heads of his alter ego, the dancer Nijinsky in the role of Petrushka the clown. Around 1947, Kline had finally closed in on his signature style, which fully emerged (by one account) after the revelation of seeing his drawings enlarged with a Bell-Opticon projector. Thirty-nine years old when he met Joan, he had never had a solo show.

Wild as she was for Kline’s bold abstractions, Joan took little from them save permission to throw out her academic ballast. One could not really mine Kline’s work. Asked why it so captivated her, she would point to its “crudeness and accuracy.” In fact, her feelings about the paintings were inextricable from her friendship with Franz, whose disarming warmth tinged with sadness truly moved her (and many others) and whose willingness to take her seriously as a painter she never forgot. Years later she would speak of how very generous Kline was

about other painters, which is very unlike many painters. He would say, “Gee, trying to do it, Joan, is great, I mean, it’s not so bad. Look—look at that,” about a young, unknown person, anybody. “It’s great. Come on, do it.” This is really true. He was so honest and not snobby, not saying: “Why don’t you forget it—get a job or something?” Always generous. No, he really never forgot and always helped other people … Absolutely marvelous.

Joan’s account of Franz’s encouragement in the midst of a difficult, doubting world finds echo today in tales of her generosity to young and struggling artists. For Franz and Joan, painting and painters were supremely important: Joan would pass on what the older artist had given her, what he called “the dream.”

Not long after meeting Franz, Joan stood knocking at the door of the painter who had first sent her heart racing.

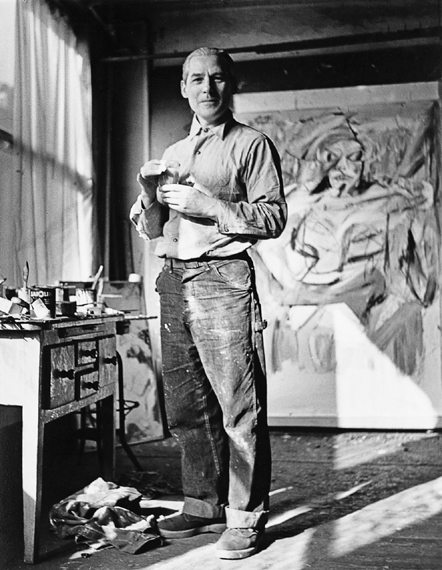

Though Bill de Kooning’s debut one-man show, at Egan Gallery in 1948, had confirmed his reputation as a rising star, it had not lifted the forty-three-year-old out of dire poverty. Joan found him in a chilly, cavernous Fourth Avenue studio doing battle with the Attic-like Excavation, a painting today considered a masterwork of the twentieth century. (As she viewed Excavation in various stages during her several visits that early spring, Joan kept thinking: “Why doesn’t he stop? It’s finished!” But, famously unwilling to let go, de Kooning continued to lavish pigment upon his canvas, scraped, painted, and pushed on.)

Looking like a sturdy blue-eyed Dutch sailor, this product of an unstable Rotterdammer working-class family had apprenticed at a decorating firm, then studied at Rotterdam’s Academy of Fine Arts and Techniques, where craftsmanship reigned. At twenty-two, he had stowed away on a U.S.-bound freighter; by the dawn of the 1930s, he was earning steady paychecks as a display artist in New York City. Around that time he befriended several deeply committed painters, notably Armenian émigré Arshile Gorky, whose dedication to art proved an irresistible magnet to the younger man. De Kooning dropped his day job and began painting moody, apparitional male figures. After falling in love with young artist Elaine Fried (they married in 1943), he turned to pictures like Pink Angels, a metamorphosis of rosy, taffy-pulled female flesh that stops short of resolving itself into human figures, thus transmitting his feeling for content as “a glimpse of something,” as he put it, “an encounter, you know, like a flash.” His next major works comprised black-and-white fields of flat forms. Rejecting the idea that abstraction was more advanced than figuration, de Kooning considered them two sides of a coin.

As for Joan, she reveled in the felt quality, raw facture, expressive shapes, whiplash lines, and assertion of flatness in the veteran artist’s work. She studied the way he let paint fly yet built his pictures with Cézannesque rigor, the way he retained the battered remnants of the Cubist grid yet worked in figure-ground mode, setting up unstable relationships between figure (the thing depicted) and ground (the flat surface of the canvas seen as background). Time and again, de Kooning visually pulls the rug out from under his viewers, forcing them to see his admixtures of fragments as images, and then not. Her encounter with de Kooning’s paintings immediately cracked open Joan’s own. No one would mistake a Mitchell for a de Kooning, but when, years later, Joan’s acolytes expressed a need to steer clear of her siren influence, she would reply, “Do you know how many de Koonings I’ve done?”

As much as Mitchell loved de Kooning’s taut abstractions, she was less thrilled by his more expressionistic work, epitomized by the 1950–52 Woman I. In other respects, too, the artists diverged. De Kooning proceeded by trial and error while Mitchell painted additively, preferring to destroy a work in progress rather than scrape and redo. And, although both adored oil paint for its light and life, they brought different sensibilities to the medium. For de Kooning, who seldom lost touch with the erotics of the human body, “Flesh was the reason why oil painting was invented.” For Mitchell, on the other hand, paint incarnated water in its every mood, “the flow of paint,” as curator Klaus Kertess once wrote, becoming in her art “a metaphor for the flow of ocean or river, and vice versa.”

Not only did Joan worship Bill for his painting intelligence, but also she deeply respected his long struggle, ascetic lifestyle, and willingness to help. Along with Kline and, to a degree, Hofmann, this “hell of a nice guy” was accessible and encouraging to young painters. He kidded around, showed up at the Cedar with various “girls” on his arm, and washed the cups at the Club. A tense workaholic who took nothing for granted in the studio, he also stood slightly apart. Overcome with an anxiety Joan understood all too well, Bill sometimes roamed the streets, insomniac, at two a.m.

For Joan the flux of gritty, steaming-manhole-cover, glaring-morning-light, dirty-brick, din-of-construction Manhattan was inseparable from de Kooning, the man and the painter. Bill’s jumpy brushstrokes—he spoke of the “leap of space”—resonated with the dense and unpredictable play of shape and light in the city. Finding freedom in having to work “to get a view,” Joan realized that a glimpse of Manhattan sky made her intensely aware of space in a way the sterile azure dome of southern France never had: “You don’t feel courage unless you’re afraid. You don’t feel space unless you’re hemmed in.”

Bill de Kooning with Woman I, 1952 (Illustration credit 6.3)

Moreover, Bill might deliver her from Jimmie at last. Joan mentally replaced Jimmie with de Kooning, whom she now considered (as she once told sculptor Lynda Benglis) “my father.”

Months after her arrival in New York, Joan was still acquainted with few artists. Then one day she got a call from Miriam Schapiro and Paul Brach, friends of Dick Bowman during their graduate school days at the University of Iowa, where Dick had then taught. Having sublet a place on MacDougal Alley, Mimi and Paul were making prints at Stanley William Hayter’s Studio 17 that summer between Paul’s two years of teaching at the University of Missouri. Not long afterward the couple dropped by West Eleventh Street with a lean-faced, dark-haired artist friend named Michael Goldberg. During their long afternoon together (under the strange Figure and the City), Joan hit it off famously with Paul, gregarious and opinionated, and Mimi, serious and rather shy. Barney too was present—and Mike. As the hours wore on, it became obvious that Joan and Mike had eyes for each other. An erotic tension filled the room, Barney looked daggers at Joan, and the two bickered fiercely.

The eruption of Mike Goldberg into their lives (as Barney surely suspected, he and Joan started secretly meeting) roiled the Rossets’ already-troubled marriage. Paradoxically, a series of normal domestic crises then restored a semblance of harmony. Joan needed an emergency appendectomy, Barney developed hay fever, and together they apartment-hunted after learning that, for reasons now forgotten, they had to give up the little house. Having signed a lease on an expensive duplex in a brownstone at 59 West Ninth Street, where Joan could paint in an upstairs space, they flew to Havana, the first stop on what was for Barney a working vacation.

A lure for Chicago mobsters and Hollywood stars, the Cuban capital’s stylish Hotel Nacional, co-owned by Barnet Rosset Sr., lavished attention upon the junior Rossets. However, a hurricane soon lashed the island, forcing guests to evacuate, clinging to ropes. After a stay in Haiti, at the romantic Hotel Oloffson, the so-called Greenwich Village of the Tropics, where Barney worked on a short documentary about the tropical disease yaws, the two flew to the Yucatán, where they rode a narrow-gauge railroad to the Mayan ruins at Chichén Itzá. Though Joan loved Mexico as much as ever, her longing to be with Mike triumphed over her desire to revisit Mexico City or vacation with her husband. Making some excuse to Barney, who was meeting with film people in the Mexican capital, she flew back to New York and straight into the arms of Mike Goldberg. He helped her move into the West Ninth Street apartment, setting up her white-walled, stripped floor studio with a rack of reflector lights, alternating tungsten and halogen, yellow and blue.

A few days later Barney too returned to New York, and life once again fell into a semblance of routine, including the small dinner parties the couple hosted, Joan cleaning, Barney cooking. Officially a painter friend of Joan’s, Mike was sometimes invited, as were Kline and de Kooning. (Bill and Joan liked to tease Barney—who was “visually illiterate,” Joan claimed—by insisting that the taped windows of new buildings were really small Klines.) But their dinner guest list was eclectic, ranging from Marion’s friend the poet Ellen Borden Stevenson, who had recently divorced Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson, to cinematographer Leonard Stark and his artist wife Marilyn, who easily picked up that her hosts’ marriage “was not very substantial.” Indeed, the Rossets had turned to couples therapy. Joan, however, heaped scorn upon their therapist, who wanted her to draw pictures of how Barney made her feel. And the stubborn fact remained: she was wild for Mike Goldberg.

With feral joy, Joan had rushed blindly into the affair, never pausing to consider its consequences. She took what she needed. Sex, yes. But also the fact that Mike was a painter. Joan was drunk on painting, drunk on New York, drunk on Mike—all the same thing. Barney, in contrast, was merely a “civilian.”

Demanding to see her lover’s work, Joan had been walked over to Bond Street, where some of his paintings were stored at a friend’s place. The friend wasn’t home. So Mike hoisted himself onto the fire escape, broke into the apartment, and grabbed a rolled canvas, which he carried down and unfurled on the sidewalk. Gestural, impastoed, and de Kooningesque, it won Joan’s enthusiastic approval. So too did Mike’s newfound resolve to build his life around art. The two spent long hours walking, seeing museum and gallery shows, and talking, smoking, and making love on the roof of his building on Ninth Street near Broadway. In the evening, Mike’s friends Cynthia and Emanuel Navaretta, an architect and writer respectively, would interrupt their strolls around the Village to drop by Joan and Barney’s apartment and, on the sly, deliver messages from Mike to his lover. “I don’t know if Barney knew what we were up to,” says Cynthia. “But we did this for several months, so we played a terrible role.”

A son of the Depression-era Bronx, Mike Goldberg had grown up in knickers with the knees worn through, a badge of parental neglect. Seldom had he felt loved by his parents, nor had he sensed much love between them. A tough kid, he ran away at fourteen (his parents never bothered to look for him), then discovered drugs and art more or less simultaneously. After taking classes at the Art Students League and Hans Hofmann’s, he was drafted in 1943. He was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, where, harassed by a self-proclaimed King of the Ozarks, he waited until his anti-Semitic tormenter was asleep, then smashed his kneecaps with bricks, and later popped up at the man’s hospital bed to finish the job by administering a concussion. During his four years in the Army, Mike served in Burma and India but not (as he later boasted in his irresistibly breezy manner) in the fabled guerrilla unit, Merrill’s Marauders. After the war came a stint as a roustabout in a remote Venezuelan oil town where he wed a visiting Martha Graham dancer (a marriage later annulled) before returning to New York and resuming at Hofmann’s, thanks to the GI Bill.

There were other pieces to Mike’s past, more than fit together, for the man was a Zelig, “a marvelous, marvelous, to put it baldly, a marvelous liar, but let’s say marvelous embellisher,” according to one friend; “a great and charming liar,” confirms another; “quite crazy,” adds a third. Born Sylvan Goldberg, he was (perhaps) a vaudevillian’s son. In any case, a perverse sense of humor and love of the limelight once compelled him to take the floor before a large crowd at the Club, improvise a twisted epic having to do with some obscure art historical topic, and get the panelists very agitated. Mike also invented degrees from St. Paul’s and Princeton and used the Waspy name “Michael Stuart,” until Joan badgered him out of it. At the same time, he flaunted his street savvy, claiming, for instance, that he could get anyone a deal on anything. “Mike used to say ‘I can get canvas for you at a great price,’ ” remembers Paul Brach. “And he’d pay the full price for a load of canvas and write bad checks for it, or something like that, just for the prestige.” He owed everyone money. Still, many found this white hipster and finger-popping aficionado of bebop and blues—another Goldberg persona—frankly seductive. “Hey! Gimme a pig’s foot and a bottle of beer,” he and Joan would greet each other, with a nod to the Bessie Smith classic.

Joan, for her part, glossed over Mike’s mix of casual dissimulation and brutal honesty. He was a painter, and she believed that good painting was necessarily honest. Never tallying up Mike’s good and bad points, she loved him recklessly and unconditionally. Those vaguely troubled glass-blue eyes, those classy cheekbones, that voice fusing the resonance of a Shakespearean actor with the glibness of a deejay, that sexy belly, that grab for her ass when they met—God!

Years later Mike figured out that Joan had fallen for a bad-boy Jewish “Noo Yawk” artist because she was still rebelling against her parents. In any case, her sense of self became inextricably tangled up with Mike. Together the two lived and breathed the urgent and dangerous adventure of painting. “Painting could change the world then,” said Mike. “And within that climate, Joan and I … existed.” Feeling “omnipotent,” she brushed off her demons: here was the more she had long wanted. Her “vision of what life could be,” Mike discovered, “was a helluva lot broader than most of us had.”

“Darling,” Joan murmured, “I can’t look at you enough or feel you enough … blue eyed one.” The following summer she wrote,

I know a man with blue black eyes and a blue shirt and a beautiful belly. He told me there was so much to believe in and I must memorize it so neither of us will forget. He showed me a fall, a winter and part of spring and in the summer there were orchids. He showed me a fear and a hope and a twitter in the park. I saw his painting through a glass by the ashtray. His name and his past I don’t know—I see his eyes and I love him.

A half century later, when Joan was dead and Mike could find nothing good to say about her, some tender ghost nagged, and he quietly confessed, “I was very much in love with her.”

That fall of 1950, one shatteringly beautiful exhibition after another left Joan “dizzy and silent”: Anne Ryan’s splendid small abstract collages at Betty Parsons, Franz Kline’s powerful calligraphy at Egan, Hans Hofmann’s exuberant painterly abstractions at Kootz. The following year would bring the Museum of Modern Art’s important Matisse retrospective, but first came another bombshell: the Whitney’s magnificent Arshile Gorky Memorial Exhibition. Some of these paintings Joan knew from Gorky’s 1948 show at Julien Levy, but the Whitney retrospective (which she and Mike saw weekly for the six weeks of its duration) laid out an even more dazzling array of the great Gorkys, among them The Liver Is the Cock’s Comb, The Leaf of the Artichoke Is an Owl, Diary of a Seducer, The Betrothal II, Agony, and The Plow and the Song.

Born Vosdanik Adoian in Turkish Armenia around 1904, young Gorky had deeply absorbed the complexion and culture of his native region. His childhood was devastated, however, by the Ottoman Turks’ persecution of Armenians in a campaign of extermination culminating in a forced death march that took the lives of nearly one million people. Fifteen-year-old Vosdanik watched his mother die of starvation. The following year, he arrived in the United States, where he re-baptized himself Arshile Gorky. Whether stalking along New York sidewalks in a black greatcoat or zoning out in solitary peasant dances at parties, Gorky cut a dramatic figure. With extraordinary discipline, he apprenticed himself to Uccello, Ingres, Cézanne, Miró, and Picasso by painting his way through their work. His encounter with the exiled Surrealists in the early 1940s precipitated virtuoso canvases at once intensely felt and radically new. A series of personal tragedies overtook him, however, and, in July 1948, at age forty-four, he committed suicide by hanging.

In the late work that took Joan’s breath away, Gorky’s brushstrokes of calligraphic precision and seaweed fluidity slip among undulating veils of smoky, translucent color as forms hovering around the threshold of legibility make bittersweet allusion to feathers, claws, insects, plows, waterfalls, and erotica, evoking the artist’s childhood and adult domestic life. Thinning his paint with turpentine, Gorky unclasps line, color, and form and makes flawless wild gardens of figures and ground.

Joan’s passion for the Armenian-born painter flowed in part from her recognition of a kindred lyrical temperament. As intimate, volatile, and emotionally precise as lyric poetry, Gorky’s pictures make paint newly visible as poetry does language; like lyric poetry, it is “a highly concentrated and passionate form of communication between strangers.” Portmanteau images of present and past, Gorky’s oils also repossess his childhood. How My Mother’s Embroidered Apron Unfolds in My Life, for instance, plaits then and now in a manner recalling the words of Vladimir Nabokov: “I confess I do not believe in time. I like to fold my magic carpet, after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another. Let visitors trip … This is ecstasy.”

Around the same time Joan began diluting her pigments with turpentine, expanding her formal vocabulary, changing her paint handling, and freeing her forms as if untying the black outlines of The City. Two or three kinds of edges gave way to a profusion. Lines scrambled and skimmed the surface. Shapes pullulated. From the motifs she had painted repeatedly, especially the Brooklyn Bridge, she salvaged certain forms—a section of pier, rippling cables, bits of flotsam, a triangle of water glimpsed through trusses—which she used (a lesson learned from both de Kooning and Gorky) neither representationally nor symbolically but expressively. Yet by no means did everything change. Her new work retained the yellowish gray concrete-reflected light (more matter-of-fact than Gorky’s), scruffy line (less fluent than his), and active center–inactive edges (versus his implied horizon) of the old.

By the time the Gorky show closed in February, Joan again had a new studio, at 51 West Tenth Street (which was to East Tenth, the legendary main vein of Abstract Expressionism, as Park Avenue South to Park Avenue). A romantically shabby pre–Civil War structure designed for painters and sculptors, the Studio Building had seen many vintages of artists, from Winslow Homer to William Merritt Chase to Kahlil Gibran to Philip Guston. Consisting of three stories of ateliers surrounding a skylit central gallery occupied by a fashion photographer, it had wide wooden stairs, long dim corridors, and wainscoted walls, which lent people’s voices a rich resonance. Joan’s second-floor studio, soon cluttered with rolls of canvas, half-finished paintings, tins of turpentine, pie plates caked with paint, and other detritus, boasted the single luxury of a coal stove, smack in the middle. The toilets were down the hall, but, mensch that she was, Joan peed in her cold-water sink and offered the same to visitors who asked for the john.

An escape from Barney and a hideaway with Mike, Joan’s space in the Studio Building, where she was jokingly called “Jana Mitch” (the super’s version of her name), brought new friendships. From time to time, tenants would phone people they knew, chip in for cheap booze, and fling open their doors. At one such party, Joan met painter Jane Wilson and her husband, writer and arts maven John Gruen. Soon the Gruens and the Rossets were inviting each other to dinner, as Gruen recounts in his chronicle of the 1950s scene. At first, he writes,

our function was to bear witness to their endless fights. It was like a game in which a naïve audience was needed for “the performance.” I vividly remember one dinner party Jane and I gave in our brand-new, freshly painted apartment on Bleecker Street. We had finally moved out of West Twelfth Street, and the first thing Jane insisted on was immaculately white walls. It was an intimate little dinner—just the four of us by candle light. Things started out smoothly enough, until Barney noticed that Joan was reaching for a second helping of food. “I wouldn’t eat that, if I were you,” interjected Barney, “you’re getting fat around the middle.” With that, Joan took a ripe tangerine out of our fruit bowl, stood up, and aimed it with enormous violence at Barney’s head. Barney ducked, and the tangerine landed with splattering force on our virgin walls. Thus began one of the more memorable of their many fights, with a barrage of four-letter words filling the air, mercifully replacing the tangerines.

That April all hell broke loose. One day Mike walked into Barney’s Fifth Avenue bank, wrote a check to himself for $400 (using one of the blanks available on the counter), forged Barney’s signature, and cashed it. To an impoverished artist, $400 seemed an immense sum, yet gossip on the streets put Barney’s fortune at an unfathomable $55 million. As it happened, Barney had not been using that account, which was virtually empty. When he received an overdraft notice, he responded that he hadn’t written any checks. The bank put two and two together and called the police. Mike was arrested and jailed in the Tombs pending a hearing.

Shocked into a state of “gray, gray emptiness,” Joan barely functioned. By day, she sat on the floor of her studio, chain-smoking, shaking, and crying; by night, she mentally composed an endless letter to Mike, in which she accused herself of pressuring him and abetting his fantasies. Her omnipotence had been shattered, her rose-tinted glasses knocked to the ground. Days passed. She couldn’t see Mike because visitors were barred from the Tombs. Finally she took pen in hand:

I have no words even for what I feel—I wouldn’t want to because you have it worse than all of us—but I have gone through the worst thing in my life—real reality as they say—and it’s small compared to yours. I’ve learned to be honest I guess and that’s it—and maybe adult—just maybe—I’ll try very hard and for you too. It seems strange now to exist at all … We’ve both got to make some kind of inhuman effort to stand it all—to straighten you out. It will take time—a hell of a lot of courage and I do believe in you—no fantasy there anymore either but something very real.

With Mike awaiting his hearing, it came as a relief to Joan to help his parents close the apartment he could no longer afford to keep. She picked up his laundry, packed his winter clothes in mothballs, and parked his canvases in the hall at West Tenth Street. Operating on a loan from Martha, her friend from Smith (how could she take money from Barney?), she paid Mike’s back rent, settled his bill for art supplies at Rosenthal, reimbursed Guston for the six yards of canvas Mike had borrowed, and forked over the forty bucks he owed Milton Resnick.

Ironically, her relationship with Barney improved. He refused to press charges—in fact, he was “extremely nice” about the whole mess—but now he insisted she choose between the two of them. She couldn’t. Leaving Barney felt no less impossible than not leaving him. And if she did have to choose, she was determined “for once” to be an adult and make her own choice, not her parents’ or Barney’s. She asked him to wait. Resolved to act despite her depression, she then purchased a cot, had a hot-water heater installed in her studio so she could bathe in the sink, and moved the rest of her belongings to West Tenth Street (while continuing to spend time with Barney on West Ninth). She was certain of only two things. First, she had to be financially independent, which meant finishing her MFA and getting a teaching job. (In her last year at the School of the Art Institute, she had racked up all but the non-studio credits for a graduate degree.) So she arranged to enroll at Columbia that summer as a special student. Second, she needed to step up her sessions with her new analyst, Dr. Edrita Fried. Among their art friends, only the Navarettas knew what had really happened to Mike (others had been told he was traveling), and Joan ached for sympathetic understanding. Feeling closer than ever to her lover, she nonetheless wanted to crawl into “someplace without any light at all.”

Viennese-born psychoanalyst Edrita Fried, named by her actor parents for a sylph in an obscure classic of the Germanic stage, had grown up in a household where Lutheran asceticism tempered bohemian emotivity. Deeply shaken during her adolescent years when her father deserted the family, then unexpectedly died, she had nonetheless weathered the crisis and gone on to earn a doctorate in English literature. Beautiful, shy, theatrical, and skilled at masking her plebeian origins, this young intellectual tripped lightly through the Vienna of Zweig and Berg. At a Beaux-Arts masquerade ball, she met her husband-to-be John Fried, a law student from a distinguished Jewish family. Hitler’s annexation of Austria made their meeting an end as well as a beginning: after the two married, they fled Vienna, eventually landing in New York, where Edrita trained at the Postgraduate Center for Mental Health and earned a license as a non-MD psychoanalyst. Joan was one of her very first patients.

Though dismissive of mindless optimism, Dr. Fried worked from a core belief in humans’ natural inclination toward healthy growth and development. In those early days of her practice, she adhered rather strictly to Freud’s theories, revisiting her patients’ childhood memories, using free association, and regarding dreams as flares sent up by the unconscious. At the same time she saw herself as one of a new breed of analysts, giving practical advice and demystifying psychoanalysis by teaching her patients its principles and methods and urging them to help set the course of their treatments.

Ash-blond, perfumed, glamorous, and fond of décolleté necklines and pearls, Fried (as Joan called her) was a queenly presence. Mitchell was not. Yet the young artist’s intelligence, creative achievement, and gutsiness in the face of the male art establishment quickly won her analyst’s respect. As for Joan, having chosen a father in de Kooning, she now found a mother in Fried. This compassionate woman who disregarded Freud’s recommendation of opacity and emotional neutrality gave Joan the undistracted nurturing attention that the artist’s own mother had not.

The immediate task in their five sessions a week was to come to grips with the havoc wreaked by that spring’s disaster. Having conferred with Mike’s analyst, Fried issued to Joan a series of forceful instructions: install a telephone in your studio; keep regular painting hours; drop X, who is not good for you, but make friends with Y. Having vowed to run her own life, Joan promptly handed over every major decision to Fried.

One of her analyst’s directives probably accounts for the strange visit Joan paid to painter Pat Passlof at her East Tenth Street apartment. After Pat had brewed coffee and the two looked at Pat’s recent work, Joan announced, “I’ve decided to be your friend.” An awkward silence. “But there are conditions. I’m very vulnerable and sensitive, and you have to be very careful how you talk to me.” Pat replied, “Well then, Joan, I’m very sorry, but I just, I can’t be your friend. Especially with a friend, I’m not likely to be that careful. It’s when I really want to feel free. So thanks for the offer but no thanks.”

This derailment of Joan’s friendship with Pat fit into a larger picture: Joan had long ago registered that life went “along fine while I’m painting and then afterwards the bottom drops out of things.” One day she drunkenly opened up on this topic to young critic Irving Sandler, who summarized: “Fucked up inside, she grabbed for life with an intensity that often verged on fury and spilled over into insanity.” But now her hopes mounted: Fried was going to repair her “fucked-up” insides, quell her monstrous anxiety, and make everything okay.

A case study Dr. Fried published nine years later, using the pseudonym “Barbara,” describes Joan’s behavior with Barney:

When Barbara married she soon felt engulfed by the proximity of her husband. She reacted with panic and tried to salvage a sense of identity through hostility outbursts. Her husband countered by violent reproaches, which, in turn, devastated her already feeble self-esteem. Moreover, she felt almost as anxious when quarrels detached her from him as when his proximity overwhelmed her. She tried to escape the threatening closeness through a love affair … She said, “I close my eyes often. Then things frighten me less, because there is no closeness.… Then I go wild, I go on a mad binge of hostility. I recover, but I have broken up everything around me. I see Brad’s [Barney’s] face looking at me tortured, because I have been hostile.”

Flushing out her demons, Joan told Fried about her “wrong” perceptions: colored letters, colored music, colored emotions, colored personalities, boundary deficits, too-insistent memories and dreams. Unfamiliar with synesthesia as a named neurological condition (as were the vast majority of mental health professionals of that day), Fried made little distinction between Joan’s neurology and her psychology. She labeled Joan’s affliction “archaic fusion” or “symbiotic fusion.” Coined by Fried, this phrase refers to the normal mental state in which a baby feels no separateness between her own being and that of her primary love object, the mother. The analyst theorized that Marion’s too-frequent absences during Joan’s infancy had prevented the child from taking for granted her mother’s accessibility, a vital step in the separation-individuation process. Thus, Fried continued, Joan had never developed a healthy ego or established a real sense of selfhood. Stuck in a state of “symbiotic fusion,” she was not always able to cope with ego regression—the normal slippage of ego boundaries during daydreaming, drinking, falling in love, or having sex—hence her inappropriate use of hostility as psychological protection.

Back from Missouri that June, Mimi and Paul dropped by West Ninth Street one day to find Barney and Joan together. In the course of that visit, Paul casually inquired after Mike. Joan tightened, Barney turned ashen. Only after her husband had left the room did Joan reply: “Mike is in Rockland State nuthouse.” Having avoided prison by agreeing to psychiatric evaluation and care, Mike had entered a six-month treatment program at Rockland State Hospital in Orangeburg. For the past two months, he and Joan had communicated by letter alone. She had written,

Michael I miss you and it’s such pain always—You are everything I guess to me and so far away.

If I could be strong enough Udnie [her nickname for Mike]—I’ve never tried so hard. If I could give you something—only my love if it helps—if I could cry loud enough for you to hear. Hold me tight Michael—it’s so dark.

I’m kissing you—this I do all the time … I sat in the park this morning and you were with me and we talked about things that we had never mentioned and much we had and I held your hand … It’s so quiet and stays light so long and what are you thinking—Oh Mike I wish I could help you.

Someday we’ll line a room with canvas and you’ll have an enormous brush and lots of black and white and cad. red deep and you’ll paint them all at once and I’ll have my arms around you.

When at last Mike was allowed visitors, Paul drove Joan, clutching a bagful of her lover’s favorite turkey sandwiches with Russian dressing, up to Rockland. “Darling Michael,” she wrote the next day, “I still can’t believe it—closed my eyes all the way home and we were riding together—you’re alive and whole too and your eyes are still blue. Hey Udnie—we made it so far—and yesterday we were together—c’est formidable. Thought of so much I didn’t say and my feelings are so mixed and I love you so much.”

Yet Joan had been sleeping with other men, including painter Ray Parker and musician Gerry Mulligan. She and Mike had met Mulligan, probably at a jazz club, the previous September. At that seminal moment of cool jazz, the baritone saxophonist was playing and recording in Miles Davis’s Birth of the Cool nonet. When he and Joan crossed paths again that spring, they ended up dining together at the Grand Ticino. Afterward she invited him up to her studio to play Mike’s recorder, and they hopped into bed.

Not that Joan was emotionally involved with Gerry or the others. But she was irresistibly drawn to sex, to the quick, primitive, scary, and satisfying reenactment of the drama of losing one’s self in, then separating from, the other, as symbolized by the proverbial postcoital cigarette. Like many men, she felt that casual sex meant little. It did mean, however, putting on a false face with Mike, to whom she coyly mentioned Mulligan in a way that implied that their encounter had amounted to nothing more than an impromptu dinner.

That same summer, Joan was raped by an attendant at Rockland after one of her visits to Mike in Ward Four. Surely she put up a fierce struggle, yet, revealing her strong masochistic streak, she abjectly accepted the rape. Somehow it represented (she told Paul Brach) “the dark side of being with Mike.”

Joan having helped the Brachs get a place upstairs in the Studio Building, the three had grown closer. In early evening, they would often stroll over to the Cedar Tavern, the artists’ watering hole on University Place near Eighth Street. Drab and proletarian, the Cedar had murky green walls, a long bar in the front where a pair of ex-Marines served up mostly beers, and, in the back, brass-studded leatherette booths and hanging fixtures, whose white light glared through a haze of nicotine-blue. There was no jukebox or TV, just the din of talky artists, mounting as the night went on.

Savoring the pleasures of belonging to a little band of renegades, Joan had met many artists at the Cedar and the Club and kept up her friendships with others. At least once she, Mimi, and Paul dined with Bill de Kooning, who then walked with them back to the Studio Building to look at their work. Joan pulled out Mike’s too. “He seemed very enthusiastic,” she reported to her lover. “He said he’d like to go see you—you were very talented etc. We talked about Stuart Davis and Gorky and Mondrian and color and I missed you horribly.”

Since April Joan had barely touched a brush, but following Bill’s visit she cleaned the studio, trundled Mike’s painting cart into the middle of the room, stirred and thinned the globs of color stuck on his palette (using her lover’s paint felt like having sex with him), and slowly got back into a big green and black thing that had been sitting around half finished. While she loved afternoon light, she preferred working at night and couldn’t sleep anyway. At midnight she would tune in to gravelly voiced Symphony Sid’s radio program Live from Birdland and, smoking and sucking on a bottle of beer, listen to Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Lester Young, and Charlie Parker as she sat scrutinizing her canvas. But she couldn’t decide if she liked the radio on or off when she actually painted.

Leo Castelli too had been to her studio. In 1957 this wealthy Triesteborn cosmopolite would establish the Castelli Gallery, soon making stars of Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Andy Warhol, who supplanted the Abstract Expressionists as the leading artists of their day. But Castelli’s launch of a powerful art world utterly unlike the little rebeldom that enchanted Joan lay in the future. In 1951 he was biding his time, dabbling in private dealing and occasionally doing exhibitions, beginning with the Ninth Street Show.

By one of several accounts, Bill de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Milton Resnick, all charter members of the Club, had conceived of the Ninth Street Show as a means of putting the new art in front of the public in other than piecemeal fashion. Most downtown artists had never had a solo show. Moreover, many remained irate over their exclusion from the Met’s American Painting 1900–1950. Along the route between the Club and the Cedar, on one hand, and the Ninth Street studios of Kline, Conrad Marca-Relli, John Ferren, and Jean Steubing, on the other, an empty furniture store had caught their attention. After the building was scheduled for demolition, its ground floor and basement became available for two months for only seventy dollars. Suddenly serious about mounting their own salon-style show, one work per artist, they rented the space, cleaned it up, and whitewashed the walls.

The Club’s ad hoc organizing committee, especially Marca-Relli and Kline, took the lead in inviting some five dozen artists to participate (seventy-two eventually did), many of them Club members, others artists like Joan who moved in its orbit, still others so-called uptown artists. Castelli was useful as a diplomat and proxy. (Usefully, too, he paid many of the bills.) The show was cooked up in two weeks.

Castelli had ended his visit to Joan’s studio by helping carry her canvas and Mike’s over to Ninth Street. So arresting was the sight of this pair negotiating the front doors of the Studio Building that passing artist Friedel Dzubas would remember it for years to come. In fact, Castelli had told Joan he was taking her work but would have to see if there was room. When they arrived, however (Castelli having complained along the way that Joan’s painting, about six by six, was too big), de Kooning, Hofmann, and Kline (according to Joan) “all said, ‘What a marvelous painting!’ and hung it in the best part of the show.” Though the organizers took pains not to imply an artistic agenda or endorse anyone’s art over anyone else’s, Kline saw to it that certain essential works, including Joan’s, were clustered in what became the focal point of the exhibition.

The Ninth Street Show opened on a beautiful, warm, late-May Sunday evening to an unexpectedly large and keyed-up crowd, klieg lights blazing (a Kline touch), taxis on the fly. Joan loved the idea of a show organized by a brawl of renegade artists operating outside the system of galleries and museums, a version of the 1863 French Salon des Refusés (with the Metropolitan playing the role of the old-fogyish French Academy). Paradoxically, however, what was intended as a celebration of the artists’ outsider status quickly attracted the attention of the art establishment, swayed opinions, and launched a scene.

Asked by an interviewer forty years later, “And you were part of the expressionist group?” Joan replied, “I wanted to be.”

“Were you?”

“Well, I thought they were marvelous.”