New York School collagist and painter

ANNE RYAN, on the fly leaf of a notebook

My great hope was to be, if I worked very hard,

an Anne Ryan.… Why? Look—she was a lady

painter I admired. How many are there?

JOAN MITCHELL

The Ninth Street Show rang up the curtain on a new cast of characters in Joan’s life, among them twenty-nine-year-old painter Grace Hartigan. On the New York scene since 1945, Hartigan had absorbed Pollock’s alloverness and de Kooning’s figurative abstraction into the woven, brushy, outwardly expanding canvases she signed “George Hartigan” in romantic self-identification with novelists George Eliot and George Sand. Born and raised in New Jersey, Hartigan had worked as a draftsman during the war, twice married and divorced, given birth to a son, and lived briefly in Mexico. Blunt and tough, with big-boned Breck Girl good looks, she met life head-on. Leaving a party and heading to the Cedar one night with friends, for instance, she got annoyed because a certain runty painter with a too-neat ginger-colored mustache was stringing along. Not only was the man stumbly and slurry from liquor, but also he had never had a one-man show, ergo, he was a loser. Abruptly Grace pivoted and punched him on the side of the head, so hard that he shot into the gutter. She strode on: “I can’t stand a man who doesn’t act like a man!” Little wonder that when then–art student, later-reporter Pete Hamill first spied Hartigan at the Cedar a few years hence, she struck him as “looking like fifty miles of trouble out of a film noir.”

Grace’s first impression of Joan was that she had never heard anyone swear like this new girl on the block. (Grace herself was no slouch in that department.) From the start, the two competed fiercely. More subtle than her rival, Joan often resorted to the sly put-down, and she knew enough not to reveal her hand. Grace, on the other hand, was perceived as “too blatant. She sort of advertised. ‘I’m going to do this, I’m going to do that.’ ” Hartigan’s first New York “one-man show” the previous January had given her major bragging rights. Her subsequent move from abstraction to expressive figuration inspired by Old Master paintings would meet with disapproval from many of her colleagues (Joan included), but Grace would again ride high and mighty in 1953 when the Museum of Modern Art purchased her Persian Jacket. (MoMA’s curator of modern collections, Dorothy Miller, considered Hartigan the most important contemporary female artist in America.) And yet again in 1957 when Life crowned her the “most celebrated of the young American women painters.” Along the way, her high-flown “pronunciamentos” irked the hell out of Joan, while Joan’s feigned poverty had the same effect on Grace. The two were never girlfriends, but they understood and respected each other.

At the time she met Joan, Grace was living with painter Alfred Leslie in a ramshackle loft on Essex Street on the Lower East Side. A brash former Mr. Bronx who survived thanks to carpentry jobs, Alfred painted raw, let-it-all-hang-out, “make-it-tough-even-ugly” abstractions that flew in the face of middle-class sensibilities and pumped their rough-and-tumble energies straight from the streets. He liked Joan’s aggressiveness and steely determination about painting yet felt she came from another planet: Smith College, high culture, always plenty of dough for dinner and booze.

And at first both Alfred and Grace found Joan’s painting less remarkable than her personality. Side by side with a 1951 Leslie or a 1951 Hartigan, a 1951 Mitchell does look “tasty French,” as the two put it. Too correct, too academic, too finished, too steeped in Cubism, Joan’s work remained “in a corset” in terms of paint handling, objected Leslie, who had just rolled out the crudely beautiful Painting on Four Pieces of Wrapping Paper, included in the New Generation show at Tibor de Nagy Gallery.

Launched six months earlier in a prosaic railroad flat on East Fifty-third Street, this up-and-coming gallery bankrolled by Harry Dwight Dillon Ripley (scion of the prominent Dillon family) and business-managed by Hungarian-born banker Tibor de Nagy drew its energies from de Nagy’s flamboyant partner, John Bernard Myers, devotee of Surrealism, confidant of poets, and avant-garde puppeteer. Myers was pulling together a stable of the most exciting progressive young artists: Hartigan, Leslie, Larry Rivers, Elaine de Kooning, Robert Goodnough, Jane Freilicher, and Helen Frankenthaler, next in line for a show.

Unlike Mitchell, twenty-two-year-old Frankenthaler rarely let a vulgarity escape her lips, yet the two had much else in common. Willful, hardworking, literary, and rich, this daughter of a late justice of the New York Supreme Court had grown up on Park Avenue and studied at the Dalton School, Bennington, and Hofmann’s. In 1950, she saw Pollock’s exhibition at Betty Parsons, an experience as jaw-dropping to her as discovering de Kooning’s work at the Whitney that same year had been to Mitchell. Now Frankenthaler was feeling her way from Cubist-derived imagery to a lyrical biomorphism distinctly her own. In 1952, she would draw upon Pollock’s method in the wheeling, watercolor-radiant Mountains and Sea. Pouring thinned paint onto raw canvas, she created an atmospheric picture that wed pigment to fabric and thus achieved the acknowledgment of flatness required of high modernist painting as defined by her forty-two-year-old lover, Clement Greenberg.

A powerful and pontifical art critic for the Partisan Review and early champion of Jackson Pollock, Greenberg dictated that painting should turn its back on the outside world, measuring itself only by criteria internal to the medium. In Greenberg’s construction of painting’s linear progression toward autonomous formal purity, Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique would later serve to link New York School painting to the Color Field work of Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland. Eventually a standard in art history textbooks, Mountains and Sea earned the painter the badge of formal innovator, modernism’s sine qua non of greatness.

Joan claimed no particular commonality with Frankenthaler or Hartigan. In fact, she always insisted that male painters helped her more than did female painters. All the same, the three were fighting similar battles for respect on the macho New York scene, and at least once Joan called upon the others when she wanted them as strategic allies. On the eve of a Club panel on the topic of the woman artist, in which Joan and painter Jon Schueler were to participate, Schueler told her he believed that women’s creativity resided in the womb—“and all hell broke loose,” he later remembered. “Joan got Grace and Helen to join the panel, and they raked me over unmercifully.”

As time went on, circumstances conspired to position Mitchell and Frankenthaler as a polar couple of art, but, already in the 1950s, their personal and artistic differences loomed large. Frankenthaler’s well-bred haute bohemian style and infrequent appearances at the Cedar and the Club squared with her uptown allegiances, while Mitchell’s rather sloppy self-presentation and take-no-prisoners attitude were the very image of the downtown artist. Moreover, Joan detested rich girls, a category from which she excluded herself. The tension between the two also hewed to the growing artistic split between the de Kooning camp, on one hand, and the smaller Pollock camp, on the other. Joan remained an unconditional de Kooningite; Helen, aligned with Pollock, “did not go for the de Kooning satellite group,” as she once tartly put it to art historian Barbara Rose. She and Joan remained superficially congenial, yet Joan rarely let pass an opportunity to snipe at “that Kotex painter.”

Joan also tangled with Philip Guston, although she genuinely liked the painter, twelve years her senior, who taught at NYU and lived upstairs in the Studio Building during the winter months when his house in Woodstock was more or less uninhabitable. Talky, testy, intellectual, and anxiety ridden, Guston was a veteran figurative-painter-turned-abstractionist whose delicate, tortured, impastoed pinks and grays clustered near the center of his canvases. Vociferous about her likes and dislikes, Joan discounted Guston’s work, labeling it tonal painting and sniffing that it lacked vitality. A Guston, she felt, merely flaunted the artist’s sensitivity—and “so what”? One night the two argued their way through a bottle of bourbon. Guston “doesn’t like Gorky or de Kooning,” Joan reported to Mike the next day, “likes Mondrian—and more intellectual or classic or whatever you call them things. I would like to paint a million black lines all crossing like [German expressionist Max] Beckmann—to hell with classicism—this is only momentum—beautiful—agony and not in a garden.” (She was referring to Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna’s Agony in the Garden, a painting Guston deeply admired for its visionary intensity and rigorous architectural space.)

As for Mondrian, his work had preoccupied Joan too since February, when the Sidney Janis Gallery had shown nine paintings from the period of the Dutch artist’s encounter with Analytic Cubism. In his lyrical, semiabstract 1908 Red Tree, 1909 Blue Tree, and 1912 Gray Tree, Mondrian depicts, as a spiritual as well as pictorial act, a certain venerable apple tree. While retaining its airy treeness, Mondrian’s subject increasingly devolves into compressed and complex networks of lines, an architecture of space that eschews traditional perspective. The ways in which these early Mondrians move yet ensnare themselves in thickets of lines enchanted Joan. Obtaining permission from the Museum of Non-Objective Art (later the Guggenheim) to study its Mondrians not on public display, she steeped herself in the older artist’s work.

Not only the paintings of Beckmann and Mondrian but also those of scores of others passed before Joan’s eyes that summer of 1951 after she turned full-time graduate student at Columbia, taking three of the five art history classes required for her MFA: northern European painting of the early Renaissance, nineteenth-century painting and sculpture, and modern art. Sitting in the Fine Arts Library one brutally hot day, Joan mentally crabbed over this triple dose of academics as she rehearsed titles and dates for a test. Her gaze drifted out the window: “why did so many people have to paint and I couldn’t care less about half of them and in the room the people come and go loathing Michelangelo.” That half included Géricault, Gérard, Gros, and all those responsible for the “millions of horses’ rumps and Napoleons” that crop up in early-nineteenth-century French painting, about which “these people”—art historians—“can think up more crap to say.” She had written several papers, but, facing a major assignment for the early-Renaissance class, struck a bargain with Paul Brach, a critic as well as a painter: in exchange for six stretched canvases, Paul came up with “Fashion as a Formal Device in Piero’s Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba,” earning Joan an A– from Professor Smith.

Joan’s unwillingness to write the paper stemmed in part from her visceral recoil at the intellectualizing that made art history a dry-as-dust landscape. As a painter, she looked hard at the art of the past, registering everything she cared about; unlike certain colleagues who aimed to remake painting from scratch, she “tried to take from everybody.” But the arrangement of images in her mental suitcase bore little resemblance to an art historian’s taxonomy. Joan’s connections were visual and emotional; her shifts in attention—like light playing over foliage, illuminating this or that branch, picking out what was significant and alive at that moment—responded to the needs of her art. Ingres, for instance, briefly meant something because de Kooning had drawn upon the work of the nineteenth-century neoclassicist, and she upon that of de Kooning. But more vital were the paintings of Kandinsky, Matisse, Mondrian, Gorky, and de Kooning himself.

Though Joan had felt too depressed to paint much that late spring and now had to limit her studio time primarily to weekends, things were happening. She experimented with a buttery white that Mike too liked and that she felt gave their paintings a “Renaissance look,” and she was equally smitten with black. Her most recent black painting had “turned out OK,” she informed Mike, “with the help of Bach and you and [bluesman Snooky Pryor’s] ‘Come on Down to My House.’ ”

After only a year and a half in New York, Joan was developing an underground reputation: major players in the art establishment had begun to take note of her work. One was fellow Chicagoan Katharine Kuh, now an important curator at the Art Institute. Three years earlier (while Joan was in Paris), Kuh had dropped by 1530 North State Parkway, where Marion had shown her Joan’s work and then sent word to her daughter that Kuh would help her get a solo show a year or two down the road. Accordingly, the curator visited the artist in New York that spring of 1951, scrutinizing her still-wet canvases as the “terrified” Joan hung back, feeling as if she were “in a coffin” and as if Kuh, whom she feared as much as she venerated, was “talking at a great distance.” Kuh promised to write both the Whitney Museum and Alexandre Iolas, the owner of the Hugo Gallery, on Joan’s behalf. Meanwhile Barney had arranged for the distinguished Swiss-born poet, Surrealist, and critic Nicolas Calas to make a studio visit. Impressed, Calas sent dealer Betty Parsons, who represented big boys Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Barnett Newman.

The prow of Abstract Expressionism, the Betty Parsons Gallery was also a place unusually open to the work of female artists. Of the twenty-one artists on the gallery’s roster that year, eight were women; Parsons’s stable included Lee Krasner, Anne Ryan, Sonia Sekula, Hedda Sterne, and Perle Fine. In contrast, not a single woman showed at the prominent Kootz or Janis galleries, a state of affairs that reflected prevailing attitudes glorifying men as leaders, marginalizing women, and assuming that male painters would build the future of progressive art, leaving female painters to follow and domesticate. (Clem Greenberg had advised Sam Kootz not to take any women because they’d just get pregnant.) Women artists were considered women first and artists second. As for married women artists, their status as wives trumped all else: when veteran painters Janice Biala and Hedda Sterne had solo shows in 1950, for instance, ArtNews had led its review of the former with “Janice Biala, wife of The New Yorker’s cartoonist Alain [Brustlein],” and the latter with “Hedda Sterne is the wife of the brilliant cartoonist Saul Steinberg.” It was tough for anybody to get a gallery in those days but really tough for women. So women had to be really tough, Joan believed. Though keenly aware of this state of affairs, she was too proud to protest or complain. Those who did were crybabies and losers.

Still she was all nerves and conflicting desires as the art VIPs studied her work. Parsons waxed enthusiastic but said her gallery was full. She then volunteered to drop a note to MoMA curator Dorothy Miller. Miller, however, was never a big Mitchell fan, and, in the end, nothing came of this nascent old girls’ network.

Logically, Joan should have joined Tibor de Nagy Gallery, but reportedly its director, Johnny Myers, advised by Clem Greenberg, disliked her work. According to Tibor de Nagy (Joan’s lifelong friend), the artist herself decided not to join “because of those two bitches” Hartigan and Frankenthaler. Yet she keenly felt her exclusion.

Mike too would have issues with Myers. Offered a show at Tibor in 1953, when he was on probation for possession of drugs, Mike saw his paintings installed by Alfred Leslie. A few days later, however, he heard from his probation officer, who had taken the trouble to visit the show, that “this fat queer [Myers] came up [to the probation officer] and he said, ‘You don’t want to look at this. You want to look at the things I’ve got in the back,” meaning work by Hartigan, Frankenthaler, Leslie, and others. Goldberg continues, “So I took my truck, and I got all the work off the wall, and I said to Myers, ‘You know, if you cross my path again, I’ll kill you.’ He knew I meant it. I really meant it.” Leslie, however, insists that when Greenberg got wind of Myers’s offer to Goldberg, he quashed plans for a show, that not a single gallery artist defended Mike, and that Mike’s paintings never made it to Tibor’s walls. In any case, there was bad blood between Goldberg and Mitchell, on one hand, and the Tibor mafia, on the other.

Meanwhile, back in the summer of 1951, painter Conrad Marca-Relli, a prime mover of the Ninth Street Show, had brokered a connection between Joan and Eugene V. Thaw, a young Columbia art history graduate and partner in the fledgling New Book Shop and Gallery, where Marca-Relli had recently made his solo debut. Thaw had heard of this semi-socialite painter from Chicago. When he saw Joan’s canvases, he immediately offered her a slot the following winter. She hesitated, then accepted. With plans for her first “one-man show”—first in New York, first that counted—bowling along, the consistently inconsistent artist turned ill at ease: it felt so “dirty,” so “hollow,” so sick with ambition.

At twenty-six, Joan was lissome and seductively androgynous, albeit full-breasted. Sternly disapproving of makeup and jewelry, frugal about purchases for herself (she wore holey underwear), and fond of jeans, khakis, Mike’s old shirts, and loafers sans socks, she nonetheless had what her lover considered “Greta Garbo style.” Young United Press reporter Roland Pease, introduced to Joan around this time by his neighbor, the ubiquitous Johnny Myers, also saw her as “stylish, girlish.” For all of her pooh-poohing of fashion, she knew she looked good in her well-tailored trousers and her signature taupe leather trench coat.

Such a uniform made a strong statement in the early 1950s, when women wore perky dresses with cinched waists and flirty little hats, fashion magazines did not show pants, and many people had never set eyes upon a woman in jeans. Even New York School women, however carelessly thrown together in the studio, typically dressed smartly on the street. “When I go out, I’m all woman,” announced Grace, who posed for photographer Cecil Beaton in drop pearl earrings.

When gorgeous painter Jane Wilson started moonlighting as a fashion model, most of her colleagues expressed disapproval. Insensitive to the realities of living without a parental allowance, Joan openly sneered. And when Mimi Schapiro took her to Lord & Taylor to purchase a dress for one rare occasion when she deigned to don anything other than pants, Joan turned their excursion into an exercise in frustration. Dress shopping was too icky, too prom queen, too uptown.

Evenings often found Joan, Mimi, and Paul together. But the Brachs were a couple, and Joan was making her way alone through the raucous, neurotic downtown scene, where, in Mimi’s words, a woman “was rated on her looks; if she was young and pretty, it was automatically assumed that she was sleeping with the artist she came with. Then he was rated as to his ability to pick ’em and con ’em.” Nonetheless, Joan adored this tribe of artists, this “community of feeling.”

People weren’t so sure about her. Cynthia Navaretta, for one, had observed that Joan was “a strange combination of quasi-shyness with toughness. She didn’t come on very strong at first, and you didn’t find out until later how tough she really was.” At a party Joan would knock back a few drinks, then click on “like an energy machine” spewing sarcasm, loud laughter, insults, whatever it took to shake people up. Boisterous and fun one minute, she could be dreadfully hurtful the next. If she was bored, she would stir trouble, but the surest way to set her off was to venture an opinion at variance with hers. In return, remembers Jane Wilson, you’d get “a chop on the head, always public, always a karate chop on the head, so that you would be knocked on your rear.” At that point, you could either go passive or “engage in the kind of battling that … was her favorite form of entertainment.”

When she wasn’t laying down a barrage of hostilities, Joan was picking her way through a list of grievances. The embattled defender of causes obscure to everyone but herself, she would imply that nobody was true enough or honest enough, that nobody properly understood her. Her vagaries could be disarming. John Gruen, for one, glimpsed “something really rather poignant” in this “very strange girl.” But Alfred Leslie quickly tired of putting himself on guard, as one does with an unpredictable drunk. Coping with Joan required more energy than he was usually willing to expend. Sitting with friends in a booth at the Cedar one night, wearing a dungaree jacket and white thrift-shop dress shirt (painting garb, ten for a buck), Alfred was gesturing to make a point when Joan strode up and planted herself before him. Staring at the alizarin crimson and cadmium red smears on his cuffs, she started in: “Ah, no, no, no! You can’t fool us with that, Alfred!” Everyone laughed, but no one really knew what she was banging on about. Only later did Alfred realize she had been upbraiding him for supposedly pretending he had slashed his wrists.

Yet Joan often proved an extraordinarily caring human being, lavishing attention on anyone in need, especially rookie artists, and wanting nothing in return. During a hard time for painter Marilyn Stark, for instance, Joan phoned virtually every day, introduced Marilyn to the right dentist, and set her up with Fried. “Joan was my big sister,” says Marilyn. Joan told Marilyn too that she wanted to sleep with her husband, handsome cinematographer Leonard Stark (then in New Mexico filming the classic Salt of the Earth), but, out of respect for Marilyn, would not. Still, Marilyn felt privileged to know her. She wasn’t alone. Twenty-two-year-old jazz-trombonist-turned-painter Howard Kanovitz, who had moved down from Woodstock shortly after the Ninth Street Show, also gratefully reaped the rewards of the older artist’s solicitousness: she taught him about art materials, ordered that he buy his paint from Bocour, and explained “how to live, how to make it, what it was all about.”

Marginalized by temperament, age, and gender, Joan herself was and was not an insider. She had not been invited to join the Club, center stage of advanced art. Few women had. In fact, until painters Mercedes Matter, Elaine de Kooning, and Perle Fine got the nod in 1952, every one of its charter and voting members (as opposed to regular members) was male. Finding the Club scene “very anti-woman,” painter Pat Passlof once asked boyfriend Milton Resnick, a charter member, the reason for the rule “No homosexuals, no communists, no women.” Each of those groups has “a tendency to take over,” he replied.

It required guts for a woman to walk by herself into the Club or the Cedar. (The graffiti on the wall of the men’s room convey the prevailing machismo: “I’m ten inches long and all man.” And underneath: “Great! How long’s your dick?”) According to Mimi Schapiro, “Under no circumstances were you to consider yourself a human being who arrived there for the same purpose that men did, namely to establish human relations.” But that’s what Joan did.

Rising to the challenge of the “gladiatorial” (to use Jane Wilson’s word) atmosphere of the Cedar and the Club, Joan would confront anyone. Once, as she arrived at the Club still paint-speckled from work, artist Walter Kamys tossed out an offer to take her to dinner after she cleaned up, and she flipped back: “Go fuck yourself, Walter!” Another time her old Chicago and Paris friend, figurative painter Herby Katzman, walked into the Cedar, “and there were Joan and Kline, leaning against the bar. And I said ‘Hi’ and looked at Franz, and he was a different man. [Kline had charmed Katzman when the two served together on an exhibition jury.] He was loaded. And he said, ‘Anything I can do for you?’ Fuck you, boy. And then Joan was there, and I said, ‘Hi, sweetheart.’ And she kind of, ‘Hi.’ Cause when they got in the bar, there was venom dripping from the walls.” Joan had always had a knack for getting in with the right people, Herby noted, yet he liked her “a hell of a lot.”

So did Jackson Pollock. When Pollock showed up at the Cedar after the weekly appointments with his therapist that brought him into Manhattan from his home in Springs, Long Island, he repulsed most women with his drunken groping and boorish greeting: “Wanna fuck?” But Joan was unfazed by the Great Artist’s cave-dweller behavior. She groped back, and they got along fine.

Not only Pollock but any man was fair game for Joan’s grab at his crotch. One night when she was drinking at the bar, painter Landes Lewitin approached her from behind. Thirty-three years older than Joan, with a bulky belly and one glass eye, the Egyptian-born Lewitin was a curmudgeonly, self-important man respected for his deep knowledge of the craft of painting. He reached up and cupped one of Joan’s breasts in his hand. Without missing a beat, she swung her arm down and hooked him between the legs. The place froze.

Though at first some of the older guys mistook Joan for a society girl playing at artist, this ballsy, hero-worshipping little sister soon won acceptance as few other women did. Painter Nic Carone found her “a lovely girl. Wonderful girl!” Not only did he like her art but also he got a kick out of that blend of moxie and brains that had her swearing like a sailor in one breath and quoting Eliot in the next. Sculptor Philip Pavia too adored this “very serious girl” to whom he lent Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer after they had a long talk about Miller, whom Pavia had met in Paris in the thirties. Yet Joan lacked the easy wit and articulateness that allowed the brilliant Elaine de Kooning to “get away with murder.” Yeah, Joan bragged, but she never once passed out from the booze like Elaine.

In the 1950s one could hardly be a teetotaling artist, writer, or intellectual. Liquor honed one’s creative edge, loosed one’s conversational talents, eased the tensions of existence. Franz Kline, Philip Guston, Jackson Pollock, and critic Harold Rosenberg, to name four Big Men, all drank prodigiously. Big Men got drunk. On beer or—a few years later, when they had more cash—on Scotch. By then, as Elaine de Kooning put it, the whole downtown crowd was “on a decade-long bender.”

Raised by martini-swilling parents and loving the way liquor diluted her anxiety and lifted her out of the mundane, Joan had long since become a heavy drinker. She would start in around five: beer, Scotch, gin, brandy, bourbon, it didn’t much matter. (A favorite customer at Astor Wines and Spirits on Astor Place, she always had a big stash at the ready.) Never one to slur or stumble around, Joan held her liquor well, but, even among downtown artists, she consumed more than most. She was considered an alcoholic under control—or maybe not. Edi Franceschini, a young musician she met around this time, found her a “wonderful person, friendly, laughing, very pleasant … until she drank” and turned into a time bomb. One night a trio of friends, including Edi and a very tanked-up Joan, took a cab home from a party. Annoyed with the driver for some reason, she abruptly laid into him with such white-hot rage that Edi, raised on the streets of New York, got scared.

Boozing, yelling, and swaggering like a man did not, however, bring male privileges. The older guys—especially Kline, de Kooning, and Hofmann—encouraged Joan, yet they had nothing to lose by helping a female painter, who, by definition, was not a real contender. Nor did it seem in the realm of possibility for women to make common cause. At parties they fixed the food and talked girl talk. “The men would get together in studios to talk about their work,” recalls Miriam Schapiro. “The women really didn’t respect each other deeply. I don’t think that another woman, at that time, really cared about my opinion of her work. She wanted a man’s opinion.” For Joan, it was more important to be one of the boys than to think too hard about the implications of their macho attitudes for a “lady painter.”

“I have a message from Michael that he’s fine.”

“Come in.”

Joan’s doorway framed a twenty-three-year-old stripling, lean-faced and clean-shaven, with the kind of dark good looks and soft-spoken seriousness that can melt women instantly. Evans Herman had stopped to deliver Mike’s message on his way from Brooklyn uptown to search out a certain out-of-print volume of poetry, but Joan waylaid him with an offer to buy lunch. Afterward, the two took a long walk, dined with Mimi and Paul, then had drinks at Louis’s Tavern, a half-basement hangout of writers and actors on Sheridan Square. He spoke of his past.

Raised in Brooklyn, Evans Herman had trained as a pianist at Juilliard before hitchhiking down to Key West, where he spent a year writing and night-clerking for a small hotel. Back in New York, he had sent President Truman a letter protesting the policy of peacetime military training. Drafted when the Korean War erupted, he replied to his induction notice with a scrawled “I would rather not”; a second notice rated a quote from George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion: “Act 3—Eliza: Not bloody likely.” Leaving his parents’ home in Brooklyn one morning some months later for his job as an assistant English teacher at the Walden School, he was taken into custody by two FBI agents. Freed on $2,500 bail, he was assigned a lawyer who negotiated a deal that put him outside the purview of the courts by way of the Bellevue Mental Health Board. In Bellevue’s reading room, he had struck up a friendship with Michael Goldberg that continued after both landed at Rockland State Hospital. Released after three months, Evans made it his first order of business to listen to his LPs of Beethoven’s sublime late quartets: his life revolved around music. Then he set out to find Joan Mitchell.

That night, Evans declined Joan’s invitation to join her in bed, opting instead for a blanket on the floor. As he rubbed sleep from his eyes the following morning, he was startled to find those big-lidded, slightly protruding eyes staring at him. Joan had been caught off guard by a non-predatory male who didn’t see her as another notch on his belt. More precious than an affair, their friendship was nonetheless soon laced with glorious sex. Evans moved in while he searched for an apartment.

Joan introduced him to Jane Wilson, John Gruen, Ray Parker, Grace Hartigan, Walter Silver (Grace’s new photographer boyfriend), and Alfred Leslie (who was now seeing a beautiful young student named Naomi Bosworth), yet Evans became Joan’s private life, her friend away from what he called her “phony friends,” her refuge from the chaos of the Club and the Cedar, where he refused to set foot on grounds that he couldn’t stand to watch children squabbling. As sensitive and dependable as Mike was rash and unbalanced, Evans appealed to a different side of Joan. “They loved each other,” testifies John Gruen. “That was the only time we ever saw Joan Mitchell soften up. She loved this boy so much. He was no Mike Goldberg, my God, no! He was a sensitive pianist … They were entranced with each other. Quietly entranced.”

After Evans moved into a fourth-floor walk-up in Chelsea, unheated but graced with a superb view of that talisman of romantic modernism, the Empire State Building, and, more important, a good piano, he and Joan got into the habit of going out to dinner, then strolling back to West Twenty-sixth Street, where he played for her, brilliantly. They spoke incessantly of classical music, Evans using language that made perfect sense to a synesthete. He talked about seeking the right place for each sound, envisaged symphonies as rivers, and conceived of music as either vertical (Palestrina) or horizontal (Debussy).

With Joan’s coaxing, he plunged again and again into the adagio from Beethoven’s Appassionata op. 57, into Debussy’s shimmering “Girl with the Flaxen Hair” and “Clair de Lune” from the Suite Bergamasque (she loved too the Verlaine poems that had inspired Debussy), and into certain Haydn piano sonatas, the sheet music for which (marked in a childish hand “Joan Mitchell, June 1936”) she pulled out from somewhere. Her eyes dreamily closed, she would sit listening, enjoying her colors, and feeling the taps open to release her monstrous anxiety. Evans chalked up the cathartic effect of his playing to Joan’s dearth of opportunities to be romantic. Her parents and Barney, he felt, had constantly harped at her: “She never had a chance to relax. She relaxed by coming up to my apartment without sex and listening to me play.” Music, as he put it, created for the two of them “a pocket of civilization … something like Thoreau playing his flute in the woods to fortify himself against the ‘enemy.’ ” In a sense, Joan felt, she wanted “only … the moonlight—the music and the fantasy—the rest of life is a bloody bore.”

Evans Herman, 1955 (Illustration credit 7.1)

Three months after Evans’s appearance, Mike too finally emerged from “the wigwam.” On that day that climaxed so much longing and expectation, Joan drove with friends to Rockland to pick him up and take him to the apartment he had rented on Horatio Street. In recent weeks, she had been trying to keep her feelings for Mike on ice. If not, she felt she’d go crazy from desire: her rock-bottom self was as wild as ever for the Blue-Eyed One. Not only was their sex life fabulous (Joan’s nickname for Mike, Udnie, referred to Francis Picabia’s 1914 oil I See Again in Memory My Dear Udnie, in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, a painting that depicts a complex, abstracted, and erotic machine, all blades, gears, and phallic hoses), but also Joan deeply believed in Mike as an artist, and he in her. Grace Hartigan points out that Mike “had a big impact [on Joan’s art]. Joan was smarter than Mike, but Mike was very instinctive.” On the painting level, they completely understood each other. However, as they got out of the car that day, Mike accidentally but portentously slammed the door on Joan’s finger. “And I think she took that as a sign,” he once said. “Of lost love—or whatever the fuck it was.” From that time forward, their relationship was forever circling the drain.

Or maybe the incident was portentous only in retrospect. In any case, strapped for cash, Mike briefly took a factory job upstate, then started working on the loading docks at the corner of Horatio and Washington streets and driving a truck between New York and Pittsburgh. During his absences, Joan was haunted by mental images of her lover’s enigmatic eyes, classy cheekbones, and gorgeous belly, yet she continued to have sex with Evans and others. (Sleeping around was another way to be one of the boys. Like Elaine, Mercedes, and Grace, Joan made no secret of it. Why couldn’t a woman, like a man, love one person yet satisfy her physical needs with others? Sexual conquest? Sure, we can do that too.) And no sooner was she with Mike than the two were battling ferociously. He too saw others, sometimes on the sly, thus stirring up the hornet in Joan. Did he really love her? Or was it all lies? She wanted in the worst way for them to make it as a couple: “My heart and my crotch [were] so fucking open to you, and then all [the] shit closed it up … and who in hell was that babe with the bubble gum?” she later wrote Mike. Paul tried to convince her that Mike loved her deeply. But she now had “the great disease—doubt—because of the ‘lies’—and it invaded everything.”

Typically, Mike would spend the night at the Studio Building, shove off early to paint in his studio, then go to work. At the end of the day, the two would dine with friends in Chinatown or the Village and later hang out at the Cedar or hit a party in somebody’s loft, booze flowing copiously at every turn. Their happiest times together were their evening walks in Gramercy Park, followed by hamburgers and drinks tête-à-tête at the San Remo, the well-worn literary bar and restaurant at the corner of MacDougal and Bleecker.

One of Joan’s favorite haunts, the smoke- and stale beer–perfumed San Remo had black-and-white tiled floors, a pressed-tin ceiling, a dark-mirrored bar, and a clientele that included James Agee, Miles Davis, Judith Malina, Tennessee Williams, and young New York poets. There painter Jane Freilicher used to observe Joan and Mike across the room—she in jeans and the talismanic long leather coat—smoking, drinking, huddling conspiratorially over a little table, and looking “very French New Wave.”

Besides painting, jazz held the two rapt. A connoisseur of early jazz—Louis Armstrong, Buck Clayton, Bessie Smith—Mike knew everything and everybody, while Joan dug, above all, Charlie Parker, Ella Fitzgerald, and that fabulous “B. Holiday woman.” Jazz had seduced her with its urban cast, moody romanticism, blend of discipline and instinct, and aura of freedom and authenticity. Trombonist and painter Howard Kanovitz (to whom she introduced Beethoven’s late quartets) saw distinctly, however, that Joan

wasn’t really there as far as I was concerned. She was a square, and we were hip. A very clear distinction as far as I was concerned. Although Joan smoked some grass like everybody else, that didn’t make her hip … Mike Goldberg was hip. And Miles Forst was hip. And Ray Parker was hip … [But] Joan didn’t have rhythm in her soul.

She did have a near-mystical feeling for paint. Squeezed by the class she was taking at NYU (Painting of the Early Middle Ages), three weekly sessions with Fried, and a chockablock social life, Joan nonetheless painted hard all that fall. Loading her brushes with blacks, whites, ochres, blues, and reds, she was producing muscular, jostling canvases rife with ambiguities, complexities, and urban tensions, using Hofmannesque push and pull. By the first of the year, Joan had what she considered sixteen decent paintings, fifteen of them squarish and around six by seven feet, and one, Cross Section of a Bridge, six and a half by nearly ten feet. In early January these went to the New Gallery, where they were installed by consultant Leo Castelli.

Two flights above the Algonquin Hotel’s Oak Room restaurant, the New Gallery occupied the top floor at 63 West Forty-fourth Street. Up on Fifty-seventh Street, Betty Parsons had invented the white-box gallery, but the New Gallery retained the staid gray walls and abbreviated neoclassical decor of an earlier day. A modest outpost of the art world in the theater district, it lacked the cachet of a Fifty-seventh Street venue, yet, with the New Yorker a block away and Times Square just to the west, it enjoyed a little scene of its own. The cast party of the popular Broadway play I Am a Camera, starring Julie Harris, took place at the New Gallery during Joan’s show.

Her opening threw the artist into a panic but turned out okay. Marion and Jimmie flew in for the event, but, more important, her fellow downtown artists came out in force. Grace perceived “a fantastic display of youthful talent and virtuosity, without the real thing,” but others who felt Joan had been slow to assimilate avant-garde thinking now lavished praise upon her. John Gruen found her a “remarkable artist, full of fire and sweeping gestures,” and Mimi saw her as “full of talent and drive—articulate, as though [she] were ripe with intention to hold the sun in [her] orbit as long as possible.” The older men also took notice. One day Pollock strode into the New Gallery, stared hard at her paintings, then turned heel without uttering a word. According to Tom Hess, writing in 1976, another (unnamed) Abstract Expressionist elder

proclaimed ruefully that it had taken him eighteen years to get to where Joan Mitchell had arrived in as many months. He didn’t intend it as a compliment. He felt that the situation had changed so drastically between 1947 and 1950 … that younger artists could make direct contact with new ideas almost as soon as they came off the easel. Looking back, however, it becomes clear that it was a compliment; Mitchell didn’t jump on a bandwagon; she made tough decisions and she stuck to them. It took courage, skill, and a fierce delight in competition.

Most of Joan’s paintings bore the names of places or place concepts: East Side, Le Lavandou, Guanajuato, Coastline, Midwest 5 P.M. These she bestowed after the work was completed. Her 34th St. and 7th Ave., for instance, got its title when Surrealist Max Ernst blurted out as he stood before it during the installation: “Oh! But this is Thirty-fourth Street, at the corner of Seventh Avenue!”

Hired by the ever-attentive Barney to write a thousand-word essay for Joan’s announcement, Ernst’s pal, literary man Nicolas Calas, saw the work’s grounding in the material world as a relief after other avant-garde painters’ suffocating insistence upon expressing their feelings. For Calas, a Mitchell painting derived its meaning as much from shrewd omission as from subtle observation: fragmented and heterogeneous, it was “endlessly interrupted” yet forever becoming. (Not only had Barney persuaded Calas to produce this first important essay on Joan’s work, but also he paid for the announcement on which it appeared, and he personally documented the show using his old Rolleiflex.)

Joan also garnered three brief but generally positive critical notices. Betty Holliday of ArtNews praised her “savage debut” (what looked savage then looks lyrical today), while New York Times critic Stuart Preston looked favorably on the paintings’ fast-paced shapes and serial explosiveness even as he detected a certain shrillness and monotony. And Paul Brach, writing for Art Digest, singled out Cross Section of a Bridge, Joan’s first self-consciously important canvas, for its “tense tendons of perpetual energy” and “wide arc-shaped chain reaction of spasmodic energies.” Reflecting New York School attitudes about putting oneself on canvas, he heralded the show as “the appearance of a new personality in abstract painting.”

As usual in those days, nothing sold. Shortly after the show closed, however, the gallery’s co-owner, Eugene Thaw, visited the small yet elegant apartment of twenty-four-year-old William Rubin, then a conductor in training but later chief curator of painting and sculpture at the New York Museum of Modern Art. There hung a Mitchell, Rubin’s first serious art purchase, made directly from the artist, paid for in fifty- or seventy-dollar installments, and financed, in part, by the sale of two fine prewar clarinets.

On the heels of her show, Joan more or less cut Thaw dead: “She already knew she was a star.” Indeed, she was quickly elected to membership in the Club, the mark of approval that mattered to her more than anything else. A month later she participated in a Club panel about Abstract Expressionism, alongside Grace Hartigan, Alfred Leslie, painter Larry Rivers, and poet Frank O’Hara—a bunch of kids (the oldest, Grace, turning thirty the following day) sharing their tremendous excitement about what was still to come.

In her third semester of graduate study that spring, Joan took late-medieval art and advanced French at NYU and audited Wallace Fowlie’s course on Marcel Proust at the New School. Fowlie’s class coincided with her slow plow through the final volume of the “absolutely marvelous” In Search of Lost Time, which she was reading in the original French.

There were many reasons for Joan to adore Proust’s novel, including its sensuousness, luminosity, poetic language, psychological subtlety, intense opticality, and inward and outward focus. Beginning with the opening episode of the narrator’s traumatic bedtime separation from his mother, she would have seen her own childhood self in the work’s ultrasensitive protagonist. Moreover, reading Proust made her even more acutely aware of music’s capacity for delicious magnification and confusion of desire. When the novelist’s character Swann hears a stirring little musical phrase as he is falling in love, that ineffable phrase—“airy and perfumed”—unseals an otherwise inaccessible part of him and amplifies his being.

At novel’s end, Proust’s narrator discovers the secret of the bliss he first felt when, against his habit, he had tasted a madeleine soaked in linden tea that whisked him back to childhood Sunday mornings in the country. This slipping outside time explains, Proust writes, “why it was that my anxiety on the subject of my death had ceased at the moment when I had unconsciously recognised the taste of the little madeleine, since the being which at that moment I had been was an extra temporal being and therefore unalarmed by the vicissitudes of the future.” The only way to grasp and make meaningful the past, which is all that truly belongs to us, he realizes, is through art made from one’s resurrected past. Similarly, the memory of a feeling, transformed as she painted, would become the basis for Joan’s work. She would think of painting—“not motion … not in time”—as a way of forgetting death: “I am alive, we are alive, we are not aware of what is coming next.” Moreover, for Mitchell as for Proust, art had the power to transform pain into beauty and to make sense of the messes we call our lives.

Not infrequently the insomniac Joan read all night. Besides Proust, she devoured novels by Faulkner and Joyce as well as the brilliant six-volume autobiography of Irish playwright and socialist Sean O’Casey. She also kept up with newsmagazines and the Times (and always held strong opinions about current events). But, above all, poetry still held her rapt. She dipped into Valéry, reread Baudelaire, knew much of Verlaine by heart, and discovered what proved to be an abiding passion for Prague-born Rainer Maria Rilke.

Rilke’s woundedness, yearning for transcendence, feeling that ordinary life is not real life, and love of trees and stars deeply moved her. So too did his vulnerability to the external world: witness the scene in Rilke’s autobiographical novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge (which she read many times) in which the narrator remembers dining in his family’s banquet hall as a child:

You sat there as if you had disintegrated—totally without will, without consciousness, without pleasure, without defense. You were like an empty space. I remember that at first this state of annihilation almost made me feel nauseated; it brought on a kind of seasickness, which I only overcame by stretching out my leg until my foot touched the knee of my father, who was sitting opposite me.

Moreover, Rilke looked to painting, especially Cézanne’s, as a model for poetry. In late 1907, the writer visited the Paris Salon d’Automne nearly every day, seeking to memorize the work of the Post-Impressionist, whose discipline, nuance, precision, and chromatic emotion he emulated. Having visually devoured the blues that dominate Cézanne’s late work, Rilke wrote, in Letters on Cézanne (another Joan favorite), of “an ancient Egyptian shadow blue” seen while crossing the Place de la Concorde, of the “wet dark blue” in a certain van Gogh, of the “hermetic blue” of a Rodin watercolor, of “the dense waxy blue of the Pompeiian wall paintings,” and of “a kind of thunderstorm blue” in a work by the Master of Aix—fabulous stuff for the future painter of Hudson River Day Line, Blue Territory, and La Grande Vallée, among myriad triumphs of blueness.

Joan’s no-credit course on Proust that spring took her far afield from the practical considerations that had led her to pursue an MFA. As her relationship with Mike frayed and married life with Barney retreated into the past, her determination to gain financial independence had waned. That June she wrapped up her coursework with straight As and received an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She never got a teaching job, however. Instead, she kept living on the monthly stipend from her parents, peevishly because she hated having to answer in any way to Jimmie and Marion, even though she begrudged Sally the larger checks she received because she had children. At the same time Joan tried to hide from her fellow artists how very privileged she was. Still, her claims to struggle along on one hundred dollars a month like everyone else met with raised eyebrows and mostly unspoken resentment. It did not escape notice that she could afford the Studio Building; that she never stinted on liquor, paint, or analysis; that her leather trench coat was beautifully tailored; that she didn’t have to take day jobs and thus enjoyed the luxury of time. In fact, the only clock Joan was punching was Fried’s: three sessions a week, plus a new seven-member “neurotics club” that caused her to feel “the most collective” she had ever felt—no exception made for the Artists’ Club.

Joan relied on Fried more than ever. After two years, her psychoanalysis remained a central element in her life. Joan’s dependence struck Evans one midday when he met her at Tenth Street after her regular session with Fried up on Riverside Drive. Having wiggled out of her dress slacks, Joan was pattering around in her underwear when she dropped the news that, Fried having decided that sleeping with Evans was unhealthy for her, they could no longer have sex.

“Well, I’m sorry because I—are we allowed to be friends?”

“Oh, yes, yes, yes.”

More discussion, then: “I’ll leave now, because you seem very confused.”

In a sense, Evans was relieved by Joan’s announcement. Their relationship was going nowhere, and he needed to get his life together. He told himself he didn’t care.

“Marisol would like to sleep with you.”

A Paris-born artist of Venezuelan parentage studying at Hofmann’s, Marisol Escobar would shoot to fame in the sixties for her witty assemblage portraits viewed as Pop Art. Famously elegant, silent, and beautiful—the “first girl artist with glamour,” as Andy Warhol once put it—she would later have affairs with both Bill de Kooning and Mike Goldberg. (Joan’s astringent comment regarding the latter: “I imagine with all the crotch sharing, N.Y. will soon be like one incestuous royal family.”)

Evans responded to Joan’s matchmaking attempt: “This is happening so fast, Joan. You lost a lover, and now you’re playing my pimp.” That went down badly.

The Village tom-toms lost no time in spreading the news. Two days later, Alfred Leslie’s ex-lover Naomi Bosworth knocked at Evans’s door, and thus began another drop-the-hanky love affair. One night Evans took Naomi for a ride on the Staten Island ferry and caught a bad cold. Afterward they returned to her place. When his cold worsened the following evening, Naomi phoned her doctor uncle, who walked in, glowered at the young man in his niece’s bed, applied a mustard plaster to his chest, and ordered rest. After he departed, Naomi too left for class. Then the phone rang: Joan.

“What are you doing over there?”

“Why are you interested?”

“I’m with Mike, and, if you don’t get out of there, I’m going to go home with Mike.”

“You’ve been going home with Mike a thousand times. When I get well, I’ll see you, and we’ll have a drink. Right now, I need a cup of tea.”

Half an hour later, Joan let herself into Naomi’s apartment, stripped, and forced Evans to make love, mustard plaster or no. Then they squabbled over whether or not she would have to lie to Fried. Evans too was in analysis, but he considered Joan’s reliance on her analyst, not unlike the reliance of her younger self on her father, extremely unhealthy.

No doubt Edrita’s method of issuing injunctions did inhibit Joan’s progress, because it simultaneously replicated her father’s directive manner and gave her the warm, intimate attention she craved. When Fried decided that she should stop having sex with Evans, Joan felt compelled to fulfill that prescription as a step on the path to mental health, yet, like a child testing her parent, also acted defiantly, rashly asserting her own will by dashing over to Naomi’s apartment and forcing Evans to succumb to her lust. Still she remained deferential to Fried, her only hope, she felt, of overcoming her defective psychological birth. At stake was nothing less than a second chance at personality development.

At times, Joan caught herself making Mitchells. That summer wasn’t one of them, however; she felt the ground sliding thrillingly, unpredictably, under her feet. Risk meant “believing in yourself enough to push it, to never feel that you are making a picture of a painting, copying yourself.” If she wrecked a painting, she had Mike take it down with the trash; if it was working, she told Barney, “Just while I stand there putting paint on, life is maybe wonderful and beautiful after all.”

During the year since Joan had walked out of Ninth Street, she and Barney had seen each other often. Together they had taken their first trip to the Hamptons, Sammy’s Beach on Gardiner’s Bay, where Joan’s friend and former classmate, painter and designer Francine Felsenthal, and Francine’s boyfriend, Ramón, had thrown a birthday party in their portable beach house from Gimbels. It was through Francine that Joan had learned of Grove Press, a tiny, nearly moribund publishing company named for the Village street where it was founded. Grove was for sale, and Joan urged Barney to buy. He knew nothing about publishing, but why not? It sounded interesting. So for $3,000 he acquired three suitcases full of books, a negligible backlist, and the manuscript of one gothic novel. Joan then suggested he publish The Golden Bowl, Henry James’s psychologically complex out-of-print classic, which she had stumbled upon three years earlier at an English-language bookshop in southern France, and adored. Accordingly, Barney purchased the rights from Scribner’s, hired a Prince-ton professor to write an introduction, and brought out the novel. Over the years he would publish other neglected classics, along with New Left theory, world literature, Existentialist drama, poetry, erotica, Beat novels, and works of social science. Grove’s publication of D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, both banned in the United States on grounds of obscenity, and the legendary court battles that ensued, lay in the future. But already he had vowed to publish Tropic of Cancer. Barney had first read Miller’s novel during his freshman year in college at a time when a girl with whom he was desperately in love was slipping away: “There was nothing to replace her. It was like Miller, when he really lost Mona [the nymphomaniac wife/muse in Tropic of Cancer], he’s free. A catastrophe that sets him free to go out and be himself, whatever that is.” Now, facing a new catastrophe—really losing Joan—he stored his inventory in her abandoned studio and threw himself into building Grove Press.

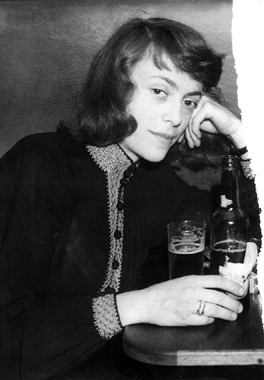

A half smile, cigarettes, beer … and a male companion later excised from the photograph? Very Joan. c. 1950 (Illustration credit 7.2)