White dawns and dusks grow warm beneath my skull

Gripped in an iron ring like an old tomb

And sad I seek a vague and lovely dream

Through fields where sap begins to strut and swell

The following April, Barney traveled to Chicago to divorce Joan. Illinois had liberal divorce laws, and friends there were willing to testify that he was a resident.

Joan, however, opposed his move. Not unhappy with the status quo, she wanted an open but mutually supportive marriage à la Elaine and Bill de Kooning, who lived apart and had many affairs yet remained committed in their own fashion. Don’t get divorced, she’d been urging, I’ll come back. But she hadn’t.

The night before the hearing, Barney called Joan in a last-ditch attempt to shock her into returning. Again, she told him to drop the idea of divorce, but he felt he had to go through with it. On May 14, 1952, Superior Court Judge Julius Hoffman (later notorious for his handling of the trial of the Chicago Eight) granted Barnet L. Rosset Jr. a divorce from Joan M. Rosset on grounds of desertion. Through her attorney, Joan had contested Barney’s assertions that he was “a good, kind and dutiful husband” and that she had deserted him “without any reasonable cause or provocation.” But she wanted no alimony or settlement, only payment of her attorney’s fees and restoration of full legal rights to her original name.

This divorce that neither wanted did not radically alter their relationship. Married or not, they remained (dysfunctional) family. She still treated him proprietarily; he still loved her romantically. Nonetheless, Barney started dating, among others beautiful Eileen Ford model (and later Los Angeles gallery owner) Patricia Faure, who recalls that “he was actively looking for some replacement [for Joan] and [Joan] was actively looking to disparage any choice he’d make.” When he invited anthropologist Margaret Mead to dinner but pointedly excluded Patricia, she dropped him. The next future Mrs. Rosset was German-born Loly Eckert, but, even after Loly moved in, Barney semi-surreptitiously pursued Joan, who didn’t hesitate to take advantage of his feelings. Once Paul Brach watched her try to wheedle Barney into doing something he didn’t want to do, then offer him sex if she got her way.

The divorce took place not long before Joan learned she was pregnant, reportedly by Evans Herman. In an incestuous twist, Evans had joined the tiny staff of Grove Press, where his quixotic employer put him to work packing books and managing a contest for writers from India. The young man’s future in publishing dimmed, however, after he ordered the “wrong” champagne for a literary dinner Barney was hosting, and the two never really got along. How could they when Barney was arranging with Fried for Joan’s abortion of Evans’s child? (At that time, abortion could be had legally in New York State if two psychiatrists declared that the woman was not up to the strains of motherhood.) Evans, in fact, didn’t learn of the pregnancy until after Joan came home from New York Presbyterian Hospital, exhausted, still cramping, and deeply depressed.

At twenty-seven, Joan longed for children yet knew that a baby was incompatible with the realities of an artist’s life, and acknowledged, moreover, that she herself still needed mother-love. Besides, she had the radical idea that her partner should assume half the responsibility. That eliminated Mike. Later, when Joan found out she was pregnant again, this time by Mike, or so she claimed, the two went to his place on Horatio Street and had rough sex until they provoked a miscarriage.

Not until Barney sent word from Paris, where he was scouting books, that a Frenchman was arriving to replace him did Joan’s depression ease. Finding herself the owner of a pedigreed chocolate brown baby poodle from a fancy pet emporium on the Champs-Élysées, she named the dog after George Dillon, for his good temper, non-husbandness, and luxuriant dark, curly hair. “Very bouncy and unhousebroken and sweet,” George (full names: Georges du Soleil and Georgeous George Sunbeam) took up “a great deal of time—I haven’t even time to dislike people any more,” she reported with dry humor to her old friend Joanne Von Blon. “In fact the poodle, male, is more interesting than anything else.”

By the time George arrived, the finality of divorce had led Joan to undertake the tedious business of searching out more livable quarters. (Tenth Street lacked a kitchen, a bath, and central heat.) That August she found a 680-square-foot fourth-floor walk-up in a classic if worn brownstone with a “melting staircase” at 60 St. Mark’s Place. Essentially one big room plus a cooking area and charmingly old-fashioned bath, her new place boasted fourteen-foot ceilings, steam heat, a parquet floor, and north light from three windows overlooking the street.

A neighborhood of synagogues, Ukrainian clubs, and Turkish baths, what is now called the East Village was home primarily to recently arrived Ukrainians, Poles, and Russians (and to poet W. H. Auden, who lived at 77 St. Mark’s Place). Butchers festooned their shops with rabbits hanging in furs, pushcart vendors hawked pots and pans or dished up steaming kasha and kielbasa, and (as Joan wrote Joanne) “choice young men in zoot suits [made] crime waves.” On summer evenings, sunglow lingered upon the dirty old brownstones of St. Mark’s Place, and scraps of polkas floated here and there. Joan loved it. To her, that neighborhood, especially anything east of Avenue A, was “the real New York … a haven from the Philistines … an island within an island.”

The legendary New York School studios of the 1950s are de Kooning’s, Pollock’s, and Kline’s, but the publication, in the October 1957 issue of ArtNews, of photos of Joan working at St. Mark’s, photos that epitomize the artist’s lonely tangle with paint, inextricably linked her studio too to a romanticized idea of Abstract Expressionist New York. During the thirty years she kept St. Mark’s, Joan lent it, traded it, sublet it, and hosted virtually everyone in the art world, yet found satisfaction above all in the autonomy and privacy it afforded—it was hers!

In another photo, by Walt Silver, the artist sits in her lair in front of a painting-in-progress, one hand on George, who stands sentinel. Her gaze rests upon her dog, and her right foot is behind him, so that he and she form a unit for Walt’s camera. Art historian Linda Nochlin sees this picture in light of “one of the most famous youthful self-images of the artist as a young subversive, Gustave Courbet’s Self-Portrait with a Black Dog of 1842.” Here Joan possesses the essential, Nochlin continues: her dog, her studio, her work. “For a photographic instant, at least, Mitchell is one of the boys—indeed, a very big boy, Courbet.”

By one or two o’clock most afternoons, Joan would be mentally and physically confronting her work: studying her canvas, churning up sticky globs of pigment, trying to get into the joyful, loving frame of mind—feeling a tree, perhaps, or a bridge—that would transport her to the place where painting as such would take over.

At the back of her mind lurked the art of Russian-born painter Wassily Kandinsky. Joan had first seen the early modernist’s work at Chicago’s Arts Club in 1945. During her winter in Brooklyn with Barney, she had frequented the Museum of Non-Objective Art, the idiosyncratic upper Fifth Avenue institution where recorded classical music played in the galleries in line with the ideas of Kandinsky, its patron saint. A recent exhibition at Knoedler had again brought her face-to-face with paintings like Blue Mountain (1908) and Black Lines (1913), dazzling dream landscapes in which the artist discards all but traces of the material world.

Joan was not alone among downtown artists in her enthusiasm for Kandinsky’s early watercolors and oils. Hans Hofmann deeply admired both Kandinsky’s spirituality and his pictorial structure, and Hofmann students like Helen Frankenthaler and Mike Goldberg had caught their teacher’s excitement about the European painter’s dynamic compositions, wondrous colors, and formal inventiveness. Moreover, Kandinsky’s imperative of inner necessity had prefigured the New York School attitude of truth to one’s own experience.

Taking inspiration from Symbolist reliance on suggestion and fascination with sensory minglings, Kandinsky had carried painting across the threshold of abstraction in search of the immateriality, universality, and emotional power of music, which he believed to be the highest art. His creative imagination may owe as much to the neurological as to the metaphorical and the theoretical: historians of neuroscience have long debated whether or not Kandinsky was a true perceptual synesthete. The evidence is inconclusive. Passionate for music and color in any case, he associated a musical sound and a smell with each hue, once vividly describing the euphoria of hearing Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin: “The violins, the deep tones of the basses, and especially the wind instruments … embodied for me all the power of that pre-nocturnal hour. I saw all my colours in my mind; they stood before my eyes. Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me.” Did Joan sense something akin to her own soulful colors and lightning-fast shapes in Kandinsky’s chromatic fireworks?

Around the time she moved, she had purchased a record player and scads of LPs: Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Charlie Parker, Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart, including everything she could get her hands on by Viennese pianist Paul Badura-Skoda. (So enamored was Joan of Badura-Skoda’s performances that she once dreamed she was marrying him.) As she was preparing to paint, she would click on her machine and lower the needle on a carefully chosen record. Everyone in the building knew that when classical music, usually Mozart, was blaring from the top-floor front apartment, Joan Mitchell “was in her ‘painting mode’ and was not to be disturbed,” one ex-neighbor reports. “The music was often very loud, but no one ever seemed to complain.”

Music allowed Joan to shed the burdens of selfhood and luxuriate in colors, movements, textures, shapes, and feelings. It may have raised unsettling questions, however. If authentic art was “an extension of one’s inner life at its highest intensity,” as critic Harold Rosenberg put it, should not Joan, with her scathing insistence on truthfulness, open her art to her hearsight? But how does a painter admit the emotional assault of colored music? How does she elide the boundaries between eye, ear, body, and hand? Illustrating her volitant musical landscape was as unacceptable as it was impossible. (Colored music is layered, swift, translucent, and impossibly subtle; paint is flat, motionless, less translucent, and based in standard colors.) Nor was her response to music wholly visual: beyond the airy starbursts, zigzags, and tides that accompanied changes in timbre, pitch, loudness, and key, Joan felt music on her body. (T. S. Eliot writes of “music heard so deeply / That it is not heard at all, but you are the music / While the music lasts.”) She may have begun fumbling toward what she had long mastered by the 1980s when she said bluntly of music: “I use it in my painting.”

As the late-afternoon light waned, Joan would put her brushes aside, wash up, and reach for her pewter cocktail shaker, two highball glasses, whiskey, Triple Sec, sugar, and a lemon to fix her version of a sidecar for herself and her neighbor when the latter came home from work. The woman found Joan “very tough and hard to get to know,” never “girlsy-chummy,” yet straight-arrow and decent.

Across the hall lived Robert and Muriel Gottlieb, recently back from England, where he had been in graduate school. Bob Gottlieb would later become editor in chief at Simon & Schuster, Knopf, and the New Yorker, but, at that time, he and Muriel, both a few years younger than Joan, were relatively poor and unsophisticated, so, matter-of-factly and without ulterior motive, Joan looked after them. When their electricity was turned off, for instance, she expertly snaked in a line from her apartment. No big deal. Bob thought her “a great guy.”

Similarly, Joan continued to keep a solicitous older artist’s eye on Howard Kanovitz. When she and Mike got their first look at the cramped painting space at Howie’s new flat on Seventeenth Street, they insisted it had to be bigger. “Why don’t you just break down this wall right over here that separates the kitchen from the living room?” “Yeah, I guess so.” “Let’s do it right now.” They did. As Mimi Schapiro once archly noted, Joan “could raise walls with the best of them.” Or raze them.

But not everyone liked her. She was denied insurance coverage after disapproving neighbors tsk-tsked to investigators that she was a wild partier and a drunk. “Shit,” Joan crabbed, “a single girl in America is like a Negro in the South.”

Thanks to an invitation from painter George Ortman, whom she had met at the Brachs’, Joan showed that September at the Tanager Gallery, a new artists’ co-op on Tenth Street. Four months later, she participated in the first artist-juried Stable Annual, a seventy-work “family affair” (including Pollock’s 1952 masterwork Blue Poles) that short-circuited institutions to put artists’ work before the eyes of their colleagues and rekindled the exuberant camaraderie of the Ninth Street Show to which it was heir. Then, in April, the Stable opened the first in a twelve-year string of Mitchell exhibitions.

Once home to Central Park’s riding horses, the ample, three-story Stable, at the corner of Seventh Avenue and Fifty-eighth Street, still smelled faintly and not unpleasantly of manure, especially when it rained. Its brick walls were whitewashed; imprints of horseshoes punctuated its rough-hewn timber floors. Unusual for its day, such hip-chic decor reflected the flair for gallery as theater that had helped the Stable burst upon the scene. A mandatory stop on critics’ and curators’ circuits, it also served as uptown New Yorkers’ box seat on the art of downtown’s bohemian brush throwers.

Credit for the Stable’s style goes to its enterprising owner, a twice-divorced (once from a Rockefeller) forty-one-year-old art novice and former aide to couturier Christian Dior named Eleanor Ward. Ward had laid the groundwork for her business with a Christmas crafts boutique that she skillfully parlayed into an art partnership with dealer Alexandre Iolas. After Ward and Iolas had a falling-out, Eleanor hired as the Stable’s manager the voluble Italian American artist Nic Carone, from whose short course on contemporary art she emerged an energetic champion of the avant-garde.

Aligning herself with the up-and-coming Stable proved a shrewd career move for Joan. Not only did she figure prominently on the same roster as Elaine de Kooning, Biala, Conrad Marca-Relli, Joseph Cornell, John Graham, and Marisol (the first to actually sell), but also she acquired a dealer with absolute faith in her work. Ward could be cagey and “bitchy in the grand manner,” and Joan, whether sober or drunk, regularly confronted, challenged, and intimidated her dealer, yet the two enjoyed an affectionate rapport. Eleanor recruited Joan for her artists’ advisory committee, numbering “six people (but nobody knows who the other five are),” quipped Elaine de Kooning, also a member.

In its early days the Stable retained that hey-gang-let’s-put-on-a-show spirit Joan so loved. When Carone picked up her work for the installation of this first exhibition, they tied a stack of paintings to the car’s luggage rack, but on East River Drive the rope came loose, and three or four canvases went sailing. Nic swerved and hit the brakes, and the two painters chased after Mitchells.

Joan was nervously pleased with what she was showing: shimmering, cinereous abstractions, more personal and meaningful, she felt, than anything she had previously done. Thicketed at their centers with narrow stabs, smudges, and trickles of blacks and whites complicated with ochres, reds, and verdigris and spatially steadied with soft bruises of violet and blue, they dissolve at their edges into silver blues, misty grays, oyster whites, and bald gessoed ground.

One can parse the 1953 paintings for the influences of Kandinsky, Mondrian, Gorky, and de Kooning, and one can note that they marry the permission of New York painting with the rigor of Analytic Cubism, yet they were fully Mitchell’s own. Freely admitting the subjectivity of consciousness to their negotiations between the materiality of paint and feelings of weather and landscape, these were not pictures of the world “out there” but rather pictures consonant with the world. In a comment that feels apropos of their effulgent grays and urban space-feelings (even as it misses their pulsing energies), Joan once wrote to Mike, “The rain so closed the landscape and makes a room of my house and truly makes me remember some so closed and soft rains on 10th St. and Horatio St.” A later review by Frank O’Hara underscored the restraint and inscrutability of these same paintings, “strikingly vital and sad, urging black and white lights from the ambiguous and sustained neutral surface, reminding one of Marianne Moore’s remark on obscurity: ‘One must be only as clear as one’s natural reticence permits.’ ”

Joan’s exhibition was reviewed briefly but positively (in ArtNews, Art Digest, the New York Times, the Herald Tribune, and Arts & Architecture) within a context shaped by Harold Rosenberg and Thomas B. Hess, two heavyweights, friends of Joan, who passionately believed in New York School painting.

Indeed, Joan was a frequent guest at the well-lived-in Tenth Street apartment that lawyer, poet, and intellectual Harold shared with his writer wife, May Tabak Rosenberg, and their daughter Patia, a nest of “warmth and ideas” (as Joan once waxed nostalgic) where one might find Patia reading Shakespeare aloud, Harold listening, and May “steaming up something divine.” Joan showed up regularly too at soirées at the posh Beekman Place apartment of starmaker ArtNews editor Tom Hess, a man of glamour and power, and his civic activist wife Audrey, an heiress to the Sears, Roebuck fortune. There one could observe the artist, all acerbic humor and billows of cigarette smoke, taking a verbal razor blade to someone’s cocktail party inanity or curling up in an armchair, Scotch in hand, to dish dirt or talk Proust with the urbane Francophile Tom. For all of Joan’s pooh-poohing of careerism, she had a knack for getting in with the “right” people.

The third member of downtown New York’s critical triumvirate of the 1950s, painter, writer, and queen bee Elaine de Kooning, was also close to Joan. Known for her witty intelligence, scrappy indestructibility, innumerable connections, and trenchant articles for ArtNews, Elaine championed her separated husband, Bill de Kooning, as a creative genius and worked their unconventional marriage to both of their advantages. In fact, she had affairs with both Rosenberg and Hess, Bill’s two major critical supporters. An artist and athlete from childhood, the Brooklyn-raised Elaine had much in common with Joan, who was not unmindful of Elaine’s connection to Bill. After a rocky start, the two had cut a deal: they would get along, no matter what, and Joan, reportedly, would abstain from sleeping with her friend’s husband.

De Kooning, Rosenberg, and Hess valued above all the creative act. Witness the concept of Hess’s signature series (by various writers, often de Kooning) in ArtNews: So-and-So “Paints a Picture.” Moreover, the previous fall, Rosenberg had published, also in ArtNews, his landmark polemic (and first major critical writing on art), “The American Action Painters.” In this essay, he argued that the future of American art (the definition of which preoccupied critics in the 1950s) fell upon the shoulders of a handful of artists for whom the canvas had begun “to appear … as an arena in which to act—rather than as a space in which to reproduce, re-design, analyze or ‘express’ an object, actual or imagined.” For such artists, continued Rosenberg, painting was a heroic act of self-revelation inseparable from their biographies, and a canvas no longer a “picture but an event.” Rosenberg termed these artists “action painters.” Lest Jackson Pollock, the painter championed by Rosenberg’s chief rival, Clement Greenberg, appear to be the exemplar, Rosenberg hastened to establish as the test of the bona fide existential painting act that it be rife with dialectical tension engaging the artist’s whole being. This statement, insiders knew, adverted to Willem de Kooning, famously unable to resolve a painting and famously unwilling to adopt a fixed style. (De Kooning had recently painted the raw, high-anxiety Woman I.) Rosenberg thus endorsed de Kooning as the quintessential action painter even as, many thought, he misconstrued the picture-making act. He then turned upon the painter who has remade himself “into a commodity with a trademark,” a slap at Pollock, whose drip paintings, Rosenberg implied, copped out as “apocalyptic wallpaper.”

Bristling with military metaphors and prophetic utterances, Rosenberg’s article drew a battle line between Pollock/Greenberg, on one hand, and de Kooning/Rosenberg and Hess (whose recent “De Kooning Paints a Picture” also enshrined the Dutch-born painter as Existentialist hero), on the other. Moreover, it imposed a gendered conceptual framework upon a painting attitude supposedly based in absolute freedom: the Abstract Expressionist as hairy-chested, heroically individual he-man doing battle with his canvas. In contrast, there was no overarching critical language for the tough but lyrical canvases of a Joan Mitchell who played music to achieve egolessness as she worked. Her painting, like that of other younger and female artists, did not fit the mold of modern man’s confrontation with absolute freedom and existential angst and thus was, in effect, sidelined by Rosenberg’s rhetoric.

From the late 1800s, when artist Thomas Moran planted his easel on East Hampton’s dunes and painted the sea, through the World War II era, when vacationing Surrealists substituted Amagansett for France’s Deauville, the fashionable East End of Long Island had been a favorite artists’ retreat. Then, in 1945, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner had purchased a run-down farmhouse on Fireplace Road in Springs, the town “below the bridge” from East Hampton, and this less stylish precinct began attracting a new breed of artists.

At that time most locals still earned a living from farming and fishing, but, as the lower fork of the island transformed itself into the Hamptons, blue-collar Springs supplied the carpenters, cleaning women, plumbers, and cooks who kept the richer area’s showplaces humming. A scattering of modest bungalows, plus a church, community center, and handful of stores around Accabonac Harbor, Springs boasted stands of cedar and oak, grass-tufted marshland, sandy beaches, sweet air, and sea-washed light. Manhattan loft rats lucky enough to afford summer in the country found its irresistible beauty as appealing as its low rents, which made Pollock, as some locals saw it, the nutty, lazy, boozing advance man for a traveling bohemian circus.

With the help of a real estate agent recommended by Leo Castelli, who owned a home in East Hampton, Joan, Mimi, and Paul now leased for the 1953 season (for a total of $500 or $600) a house on Flaggy Hole Road near Maidstone Beach in Springs. The meager charm of this two-bedroom, called the Rose Cottage, derived wholly from its woodsy setting and its name. The house and its furnishings were nondescript. The windows were equipped with only shutters and screens, but its wide overhanging eaves gave each of its occupants an outdoor studio on one side of the house, and all three painted beautifully that summer.

Unable to afford a share and, in any case, employed at his uncle’s box factory, Mike came out mainly on weekends. But Howie Kanovitz and composer Morty Feldman, both deeply involved in psychoanalysis, often hung out with Joan, analyzing each other’s dreams and comparing notes on their shrinks. Howie was playing trombone to the baritone sax of the wiry, black-eyed painter Larry Rivers, at the local roadhouse, Jungle Pete’s, where they all schmoozed, danced, and drank around the oak bar. And Grace Hartigan and Walt Silver frequently camped at Rose Cottage, including one night that ended with Grace sobbing in the bedroom after Paul expressed skepticism over her assertion that Larry was the Picasso of their day and she the Matisse. From the older generation, Austrian American stage designer Frederick Kiesler and artist Marcel Duchamp turned up occasionally. Around the corner lived Rose and David Slivka, a writer and painter, respectively. Though Rose felt she had to guard against Joan’s efforts to seduce her husband, she found her neighbor adorable.

After day’s light waned and work was put aside, they would all converge upon the beach. Someone might drag down an old bedspring while others collected wood for a bonfire (still legal then). Cases of beer would materialize, champagne corks pop. A fire soon crackled and soared, and an aroma of hamburgers or steaks wafted from the grill. As Joan’s notoriously out-of-control dog George tore up the sand, people would gossip, horse around, or go skinny-dipping. When they went to Louse Point, on the ocean side, a place of spectacular sunsets, fireflies swarmed after dark, illuminating the beachgoers’ bodies in pale phosphorescence. The attitude was easy and asexual, yet Joan disliked the idea of public nudity and usually sat out the swimming. On the other hand, once when they were lying in a row on their backs gazing up at the stars, she reached over and groped Paul, who had the normal male reaction. Turning her head in his direction, she murmured, “Oh! You’re not so loyal to Mimi after all.”

This was not exactly what Fried had in mind in urging Joan to adopt the strategy of seeking the least damaging forms of hostility. Yet psychoanalyst and patient agreed she was making progress. After two and a half years of analysis, Joan had a better grip on the old cycle of ego regression, tension, panic, and rage, a better ability “to look upon [objects in the external world] as things or persons existing according to their own laws and separate from her.” Having been walked by Fried through numerous “reality situations,” she now recognized many options for releasing antagonism and happily found herself able to experience quiet strength and to “feel affection, love, sex, and not have to tense up and get ready to attack.”

That summer in the Hamptons and back in the city that fall, Joan chummed around with poet Frank O’Hara. Vital, intellectual, and talky, this slender man of twenty-seven, with a fighter’s broken nose, periwinkle-blue eyes, a receding hairline, and a jaunty birdlike walk, pirouetted through life, a cocktail, half-smoked cigarette, and profusion of friends ever at the ready. His capacity for friendship was legendary.

Raised in Grafton, Massachusetts, O’Hara had served in the Navy before studying at Harvard (where he roomed for a time with Ted Gorey). After Cambridge had come a restless year in graduate school at the University of Michigan, followed by a move to New York City in 1951. Boggled by the city’s sensory excitement and chaotic energies, O’Hara could not, he famously wrote, “even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy, or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life.” From a job selling postcards and tickets at the Museum of Modern Art, he had worked his way up to front desk manager, a position he had recently resigned to join the staff of ArtNews, thus becoming poet–art critic to the Abstract Expressionists as his French role model Guillaume Apollinaire had been poet–art critic to the Cubists.

O’Hara wrote fast, revised little, and half joked that his poems, born in a staccato clamor of keys on his Royal, were unmade phone calls. Yet, steeped in a deep knowledge of literature, especially French modernism, his work was richly complex. Scholar Marjorie Perloff characterizes O’Hara’s poetry in terms of its shifts between realism and surrealism, liberal use of proper nouns as nonsymbolic fragments of real life, anti-confessional “I,” and syntactic breaks giving rise to contradictions that cannot be sorted out and thus (as in Cubism) force the reader “to accept the flat surface with all its tensions.” Sometimes called “action poetry,” O’Hara’s work insists upon its own coming into being. In many ways, it is analogous to Mitchell’s.

Frank was as devoted to painting, including Joan’s, as Joan was to poetry, very much including that of “Genius Frank.” His selfless generosity and marvelous outpourings of affection touched her. In some ways they were alike: both drank prodigiously, adored New York, relished playing the irritator, and shifted the energy of a room when they entered.

Frank had drawn Joan and Mike closer to the Tibor crowd, especially Alfred, Grace, Larry, and Jane Freilicher. O’Hara’s witty, brainy, and sensitive muse, Jane found Joan “boisterous and good humored and haranguing.” Joan’s edginess, Jane perceived, did not preclude “unexpectedly generous winning qualities.” Joan threw a party, for instance, to celebrate Jane’s first solo show (a figurative painter, she was not direct competition), and, several years later, she would again fête Jane, on the eve of her wedding. (“I’m serving cognac and nothing else, and I don’t want to hear any bitching,” Joan warned anyone within earshot before that occasion.)

Jane was also close to poet John Ashbery, who had moved to Manhattan from Sodus, New York, via Harvard. Playful, low-key, and ironic, Ashbery had poems “going on all the time in my head, and I occasionally spin off a length.” He too started palling around with Joan, who brought “a festive quality” to their evenings together, he thought, even as she turned simple conversations into something like “embracing a rose bush.”

They all saw each other everywhere (May Rosenberg had dubbed the downtown scene a “flying circus”), from Nell Blaine’s loft, where the Virginia-born painter led the drumming at wild parties, to the San Remo, where they sat around drinking and smoking Camels and the poets exchanged what they had written that very day.

Along with O’Hara and Ashbery, poets James Schuyler, Barbara Guest, and Kenneth Koch had blown off the dust that had settled upon American poetry, collaboratively reinventing it as a fresh, witty, anti-academic medium that drew as easily from bits of overheard conversation, self-invented games, and the tabloids as from the poet’s imagination. In the same way as New York School paintings asserted themselves as pigment on canvas, New York School poems stacked up as words on a page. Abstract yet intensely in the world, confounding to the literal minded, poems and paintings shot forth in the same electric atmosphere. Poets and painters were each other’s inspirers, collaborators, audiences, and critics, the poets, Schuyler once wrote, profoundly affected “by the floods of paint in whose crashing surf we all scramble.” In a prophetic 1951 essay read at the Museum of Modern Art, poet Wallace Stevens had proclaimed that the “world about us would be desolate except for the world within us. There is the same interchange between these two worlds that there is between one art and another, migratory passings to and fro, quickenings, Promethean liberations and discoveries.”

As it happened, Joan and Frank had a huge fight over Wallace Stevens, after which it took weeks for their friendship to right itself. Then came a hysterically funny and long-remembered incident involving the two drunkenly toppling all over each other. (Even years later, O’Hara closed a letter to Joan, “Kisses and falling-downs, Frank.”) This moment of supreme silliness probably took place late at night: both Joan and Frank had a gift for twenty-four-hour living, and it was not unusual for them to end up a rowdy or mellow duo at three or four a.m., after everyone else had dragged off to bed. Elaine de Kooning recounts how one night she and Franz Kline

were sitting alone at a table at the Cedar when the waiter came over and said, “Last call for drinks.” “We’ll have sixteen Scotches and soda,” Franz said grandly. “Sixteen?” the waiter asked, looking around to see who would be joining us. “That’s right,” Franz said, “eight apiece.” Frank O’Hara and Joan Mitchell came in from a party just as the waiter was filling up our table with glasses and gleefully joined us.

In the morning a bleary-eyed Joan would walk George in nearly deserted Washington Square, where she might cross paths with Hans Hofmann, who would doff his hat and inquire: “Micha, why aren’t you working?” Or linger on a bench with painter Ad Reinhardt, indulging the theorizing of the curmudgeonly anti–Abstract Expressionist geometric abstractionist. Or sit alone, thinking of Mike.

Their relationship had staggered on. That spring Mike moved to Second Street between Second and Third Avenues, where his neighbor, composer and pianist Alvin Novak, was startled by the fearsome sounds of Joan and Mike trying to kill each other and amazed at how fiercely Joan held her own. When she turned up “really black and blue,” with bruises and black eyes half-concealed by sunglasses, friends were at a loss for words.

That January or February, Frank had introduced Mike to a pudgy, full-lipped dark-blond poet from Boston, the same woman who, dressed “as a louche femme-fatale,” had days earlier stolen the show at Larry Rivers’s costume ball for which Joan and Alfred had painted enormous paper murals and other artists had created outlandish outfits for the poets. Mike had then embarked upon a “violent affair” with Violet Ranney Lang, aka Bunny.

The daughter of a Boston society woman and a King’s Chapel organist, Bunny Lang lived with her widowed father in a deteriorating Bay State Road brownstone. Though raised in old-money circles, this stagy eccentric, later the subject of an irresistible posthumous memoir by her friend, novelist Alison Lurie, preferred dirty dishabille and ratty thrift shop gaudery to pearls and a hat. To pay off her debts (the family fortune had dwindled), she took a series of odd jobs that she treated as acting opportunities, most famously as a chorus girl at Boston’s Old Howard burlesque theater. She also wrote, directed, produced, acted, and played the role of querulous ringleader at the avant-garde Poets’ Theatre in Cambridge, a bid to revive poetic drama. Members included Harvard and ex-Harvard poets John Ciardi, Richard Eberhart, John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, and Ted Gorey. Moreover, as V. R. Lang, she had published in Poetry and the Chicago Review. The production of her verse play, Fire Exit, at the Amato Opera Theatre had brought her to New York that winter.

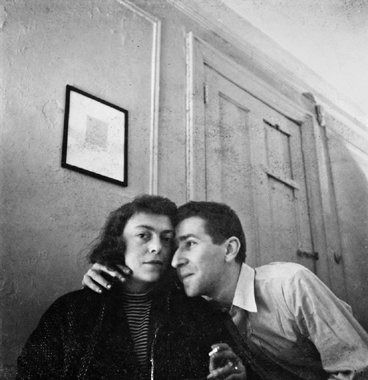

A lull in the storm: Joan, age twenty-nine, with longtime lover Michael Goldberg, c. 1954 (Illustration credit 8.1)

Back in Boston in March, Bunny wrote Mike, “You are my love and you are a wonder and I want to live with you more than anything else in the world.” They agreed he would come up to “ask her old man for her hand,” after which they would marry and live in New York, where she would find a job and support him like any good long-suffering Abstract Expressionist’s wife.

“On April 9, as announced,” reports Lurie in her memoir, “Mike arrived in Boston, a city which he had never before visited. He proved to be a medium-sized young man with black hair, burning eyes, and a large pale bony face, dressed as an abstract painter. He said almost nothing at all and moved everywhere with a quiet, catlike walk in sneakers spotted with abstract paint,” sometimes steering Bunny by the back of the neck, which was not done in Boston. Throughout Mike’s visit, the crusty Mr. Lang had kept his own counsel on the matter of his daughter’s suitor, until finally he summoned Bunny for a private conversation in which he proved himself a vicious anti-Semite. Furious, Bunny and Mike swept off to New York. Friends awaited telegrams announcing their marriage.

But they never came. For months Bunny had been undergoing tests for flu-like symptoms, and, around this time, they confirmed a diagnosis of Hodgkin’s disease, a type of lymphoma at that time incurable. Unable to handle this looming catastrophe, Mike put the brakes on the relationship. Moreover, he had continued to see Joan, as if nothing had changed, and a third woman too. After several weeks, Bunny returned to Boston alone.

Bunny’s very existence gave Joan apoplexy, her rival’s easy command of Mike’s heart casting into relief her own failure at love and stirring up a demon’s nest of fears of abandonment. Yet long before l’affaire Bunny, Joan had stopped allowing herself the vulnerability of blissing out in Mike’s arms and Mike had wearied of Joan’s excessive emotional demands. When she spoke, he listened, she felt, “at a great distance if at all,” and this ambiguity and hostility were far worse than Sturm und Drang. “I would like to be loved or destroyed by you,” Joan told him, “but not left crippled like an insect.”

Yet she herself was leading a messy, reckless, and distracted life. Her many lovers included painter Jon Schueler, with whom she went home one night after a party at Guston’s studio. Jon was stunned by the beauty of Joan’s breasts. But when he tried to get intimate again a few days later, he was dismissed: that was over, now they would be just friends. Another former sex partner who crossed paths with Joan at the theater one night was heartily greeted, “Oh, boy! You were shitty in bed.”

One affair mattered, however, more than the others. The grandson of famous Harper’s Weekly illustrator Rufus F. Zogbaum and son of a Navy admiral, Yale graduate Wilfred Zogbaum had abandoned a successful career as an advertising photographer to become a sculptor and a painter of foamy-white abstract cloudscapes infused with the lights and colors of Springs. He and his wife Betsy lived with their six-year-old son in a renovated Coast Guard building on Fireplace Road. The marriage was disintegrating, however, and Betsy stood at the threshold of a long, vital relationship with Franz Kline.

That summer, Joan, Mimi, and Paul again rented together in Springs, this time Bossy Farm, also on Fireplace Road. The Brachs would take the house, and Joan the former duck shed out back, and they would share the kitchen and bath. By then Zog had moved to a fisherman’s cabin just down the road.

Given the intelligence, charm, and enthusiasms of this artist, French speaker, and music intellectual with an impressive record library and an abiding passion for Bach, an enduring romance might have been born. Joan was telling everyone she had left Mike for Zog, but, in fact, the chemistry was lacking for anything but a deeply affectionate friendship.

One day early that summer, as Zog was attempting to start the cabin’s defective space heater, he dropped a lighted match into the fuel tank, either by accident or out of frustration. The resulting explosion blew the building four inches off its foundation and sent him to the hospital with third-degree burns. Joan’s summer would unfold no less disastrously.

On June 9, after a sleepless night, Joan hitched an early-morning ride out to Springs with Harold Rosenberg, who owned a house on Neck Path. Along the way, the two stopped at the red Victorian on the edge of Bridgehampton that Bill de Kooning, Ludwig Sander, Elaine de Kooning, and Franz Kline were sharing that summer. The late-carousing household barely stirred, except for Franz, “charming and unshaven,” who fixed the visitors dry martinis and caught them up on the latest: Jackson Pollock’s broken ankle.

A day or two earlier, Franz, Bill, and Lutz had driven over to East Hampton to collect furniture and books they were going to store for their friends Don and Carol Braider. Meanwhile, Jackson had pulled up to the Red House in his Ford. He was now painting little, drinking hard, and making himself unwelcome almost everywhere. Nervous to find herself alone with the liquored-up and glowering artist, Elaine had phoned Bill at the Braiders’. After he returned, the men started carrying books to the basement, all the while bantering and roughhousing. Then Jackson tripped, and Bill tumbled over him. Jackson’s ankle snapped. Even as Carol was driving Pollock to the local clinic in her station wagon, stories of what seemed a symbolic bout began flying around the art world. “At least he’ll be quiet for a few days until he can wield his cast through Hattie Rosenberg’s glass,” Joan dryly observed, referring to the pianist who lived on Louse Point in a spectacular home designed by her architect husband.

Thanks in part to a groundswell of confidence among artists, Springs was fast becoming East-Tenth-Street-by-the-Sea. Now that their work was beginning to sell, more painters could afford summer in the country. Dealers Sam Kootz and Sidney Janis were around, vacuuming up the biggest names and taking the line that, as Eleanor Ward paraphrased Kootz’s pitch, “Now you’re successful you need a knowledgeable man around. You’ve had that scene and now you need the real thing.” But Eleanor too was shopping for artists, as was Martha Kellogg Jackson, heiress to a Buffalo chemical fortune, who was buying directly from painters for her new East Sixty-sixth Street gallery. Not from Joan, however. During a visit to the Rose Cottage the previous year, the dealer had, in Joan’s opinion, asked stupid questions and made insulting comments. With her usual point-blank directness, the artist had chased Jackson away: “Why don’t you leave?”

Gallery politics notwithstanding, summer in Springs brought a chance for artists to catch their collective breath in the midst of the long struggle to make it. Most were working—few as intensely as Joan—but they also indulged in beach walks, clambakes, cocktail parties, outdoor suppers, and softball games on the Zogbaums’ lawn, where Joan played alongside Bill de Kooning, Elaine de Kooning, Charlotte Park, James Brooks, Saul Steinberg, John Little, Leo Castelli, Harold Rosenberg, Larry Rivers, Philip Pavia, Esteban Vicente, Howard Kanovitz, and Franz Kline. Pavia proved a star slugger, Rosenberg a fine pitcher (because of his bad leg, his daughter ran the bases), and Joan a third baseman who practically took the glove off someone’s hand when she blasted a ball, thus terrifying the foreign born, like the Italian Castelli, the Romanian Steinberg, and the Dutch de Kooning. According to Tom Hess’s version of an oft-told story, Franz, Bill, and Elaine once spent a long evening painstakingly painting a coconut and two grapefruits to resemble softballs. The following day a grapefruit was duly pitched by Harold to Philip:

Pavia swung, and it exploded in a great ball of grapefruit juice. There was general laughter [so much so that outfielder Castelli fell over backward] and little shouts of, “Come on, let’s get on with the game.”

Esteban Vicente came in from behind first base (where Ludwig Sander was stationed with a covered basket containing ammunition); he pitched the first ball over easily. Pavia swung. There was another ball of grapefruit juice in the air. More laughter. Finally they decided that fun was fun, but now to continue play, seriously. Rosenberg came back to the mound. He smacked the softball to assure everyone of its Phenomenological Materiality. He pitched it over the plate. Pavia swung. It exploded into a wide, round cloud of coconut … then, from nowhere, a crowd of kids appeared around home plate and began to pick up the fragments of coconut and eat them. They had to call the game.

Life at Bossy Farm was proving less mirthful. For reasons she never spelled out, Joan had soured on erstwhile best friends Mimi and Paul. Once that summer she picked up Mimi’s Egyptian-style necklace, draped it across her forehead, did a few bumps and grinds, then wrapped it around one breast, wiggled some more, and finally made of the pendant a surrogate penis. No doubt she was sloshed and going for laughs, but her performance came off as mocking and disturbed. Another time she and Mike tried to plant lice in the Brachs’ bed, a prank they found hysterically funny. Never at a loss for sly barbed put-downs of Mimi and Paul, Joan treated the two, thought Paul, as if they were “a bourgeois couple playing itself, and she was the one going into uncharted waters.”

Similarly, at a small dinner party at the Braiders’, a very drunk Joan offended her hostess when she shot down some casual remark of Don’s with a disdainful “What’s so sacred about your asshole?” Moving in a haze of liquor and smoke, she awoke each morning dreading the moment when she would remember her horrid behavior the night before. But she never apologized.

She had started taking Dexedrine, a potentially habit-forming amphetamine used to treat depression (though rendered less effective by alcohol). It exacerbated her insomnia. So too did her fear of the deep blackness surrounding the lonely duck shed. After dark, the trees outside her window looked “Seuratish and colorless,” and the wind moaned and rattled her shades. Night after night she lay in bed reading Dostoevsky until, light finally leaking into the sky, she drifted off, and the sons, fathers, elders, and prosecutors of The Brothers Karamazov trooped through her nightmares. Dostoevsky also fed her brief obsession with the gratuitous beating death that summer of a Brooklyn bum by four shy, bookish teenagers with whom she identified.

Joan’s distress went hand in hand with a growing frustration with painting. “My hand doesn’t always feel and my eye sees just clichés,” she complained to Mike. Color eluded her. With a record spinning on the turntable she had lugged out to Springs and a tumbler of gin by her side, she escaped one afternoon’s searing heat in the shade of her shack, staring critically at “one blue and one yellow pitcha—smallish and the kind one would say ‘talent’ about and not much more.” She continued,

I distrust my painting in color—I think it’s because people said I ought to—and I distrust [my painting that relies less on color] … and I hate little paintings because they’re “quickies” and big ones because they’re pretentious—and when I start cataloguing all things in this manner the real meaning isn’t there. I better get myself in order with some honesty and the ability to fail. I’ve always painted out of omnipotence I guess—pretty shaky method. Gimme a pigfoot and some dexedrine and don’t disturb my fantasy.

Joan was seeking—and, she felt, failing miserably at—“a complete synthesis of accuracy and intensity.” By accuracy, she meant rigorous structure and discriminating line that worked “in terms of describing forms, making forms work, and in terms of the lines themselves.” For lessons in accuracy, she looked to Beethoven, whose music rarely left her machine; Cézanne, whose reproductions torn from art magazines she had tacked to a wall; and especially van Gogh, whose landscapes, she felt, supremely fused accuracy with intensity. Not only was a van Gogh scrupulously built but also its every brushstroke delivered authentic feeling. Obsessed with the Dutch artist’s roiling, hallucinatory landscape The Starry Night (in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art) for its pulsing line, fabulous crudeness, violent lyricism, and painfully intense color, Joan stared at the luminous blues surrounding her that summer by the sea and ruminated about “that Van Gogh intensity idea.”

Claiming that she experienced painting in a physical way, nothing more, she did allow to Mike that, well, “maybe mystically” too. And she fell into near rapture when Barney’s fiancée Loly Eckert brought her a brilliant yellow sunflower, “an absolute headlight. I like what Van Gogh made of that starry night—to animate something—insanity and fanaticism. My painting natch is horrible.” Filled with false starts, her work again and again fell short of her exalted aims, even short, she felt, of genuine failure. But she soldiered on, destroying as much as she kept.

Then there was the “fucking, emotional bankruptcy” of her relationship with Mike. Tortured by memories of the marvelous complicity of their early days, of their old San Remo suppers, Joan felt “on the edge of my life and I’d like to get back into it. I’d like to carry it with me as Harold [Rosenberg] does in the briefcase.” After a dash into the city to buy paint, see Mike, and talk to Fried (who had a great deal to say about her lover’s continual threats to cut and run), Joan lamented in a letter to Mike,

It was sad driving back—all surrounded with the failure and so completely aware of all the reasons. The Russian Icon book [a gift from Mike] is beautiful. We do pay a high price for our sensitivity—or is this a rationalization. It’s such crap to say I need to be alone to be able to see you again. And it’s empty to say I’m sorry—but I am Mike—and guilty—and I miss you completely already and remember that strange hospital bed with gold ends and remember you’re leaving. Te quiero tanto—tanto.

Yet Mike’s visit to Springs the following weekend proved the usual disaster.

Mike was simultaneously living a long-distance drama with Bunny. “All through the summer of 1954 the affair dragged on,” writes Alison Lurie. “Mostly by mail: Bunny would not go to New York, and Mike would not come to Boston. Sometimes they telephoned, and shouted insults at each other.” Bunny suffered intensely. By fall, however, she was telling Lurie she was “getting very tired of the whole thing, at last. It is so feeble and psychopathic.” She locked herself in her bedroom and brewed revenge, needling Mike by letter: “You stopped believing in me, how did I fail you? Go to Arabia and I’ll go there too as a company typist. Go to China and the first coolie you’ll see in a rice paddy will be me. Or I’ll live in the Y at 12th and Hudson and come every day to sit in front of the Merit Company [where he worked]. A forbidding and reproachful figure.” She considered mortifying him by writing a long rant against abstract painting, signing “Michael Goldberg,” and mailing it to ArtNews or Time. Then she got a better idea.

In Joan’s letters to Mike, line after line of elegant barbed wire prose as edgy, free-associative, articulate, and as paratactic as a Mitchell painting or O’Hara poem, the painter kept reverting, that summer of 1954, to her abhorrence of the art world’s “knifing and competition.” Grace, of course, was around and issuing pronunciamentos, the latest of which had to do with excess and restraint. Grace and Larry and Ingres and a few other “great painters” were “excessive.” Jane Freilicher, unfortunately, was not. Joan had not been considered. “It’s like looking at painting at a girl scout camp,” retorted Grace’s rival, “so many demerits for peeing in bed, etc, a gold star if you shit enough.”

The whole season, Joan felt, had lapsed into one long, drunken-nauseous, ego-bloated party: at the Red House in Bridgehampton, at the Castellis’ elegant digs, at Larry Rivers’s place in Southampton, at painter Alfonso Ossorio’s estate, at the modernist Quonset-hut-inspired home Barney had recently purchased from painter Robert Motherwell, where, with Loly, he was throwing “Gatsby-like parties” around the pool. Cars were constantly pulling up to Bossy Farm too, friends stopping by, friends of friends butting into Joan’s life. She wanted to flee. The “pressure of the summer has been unbearable,” she confided to Mike. “I feel in a goldfish bowl … I want to pull the shades down … I want to hide.” Even the gregarious Elaine de Kooning was experiencing a “pleasant but nightmarish summer, parties every night, entertaining in the way a nightmare could be entertaining … too many friends, too much talk, too much booze, too much of a good thing.”

Even too many pictures. At one cocktail party at Ossorio’s, Joan and Alfonso had persuaded Don and Carol Braider to add a gallery to their House of Books and Music on East Hampton’s Main Street. Thus the carport out back (consisting of a wall, a roof, and the wooden platform where a plumber used to park his truck) was transformed into an exhibition space. Everybody participated in the Braiders’ shows. Nothing was priced at more than $300. Nothing was guarded or insured. Never again would Abstract Expressionist work, today sold for millions, be shown that casually or offered that cheaply. The Braiders’ openings should have felt to Joan like happy tribal moments, especially since she had helped to initiate them, yet she disliked these “crappy clothesline shows,” another spin of the wheel in “the rat race.”

To loosen her straitjacket of anxiety, Joan listened to classical music with Zog, took George to Barnes Hole beach, or simply commanded herself to breathe deeply. Often she felt incapable of positive action: “How very weak I am after all—and how very overwhelming any feeling is.” She had trouble sorting out time, seemed to slide into water or trees, could not always mentally distinguish herself from Mike. Would her edgeless white gin-blurry fog of depression ever lift?

The predawn hours of August 9 brought a downpour that persisted all day, cutting a stifling heat wave. Having dashed her supplies inside the shed, Joan started a “cad yellow pale thing,” then put it aside to work on a half-finished canvas. A third oil, small, with a problematic green square, awaited clear weather so she could take it outside and examine it in full light. Inside the shed, the air was pungent with turpentine and cigarette smoke. She felt acutely alone. She had given her adored George to the dog-loving Braiders because, she told Carol, he was getting too sexy and was always trying to mount her. As for her pictures, she had “put all my nickels in the slot machine” and, pull the lever as she might, nothing was paying off. She had just ripped apart four failed canvases. Why drag another brush across another piece of linen?

Four days later Joan wrote Mike a chatty letter, ending, however, on an ominous note: “Sweetie pie the ship is rocking at high noon. You paint for both of us for a while—and miss me.” She would leave him on her terms, not his. Placing Mozart’s Don Giovanni on the turntable, she lowered the needle, turned up the volume to cover the drumbeat of the rain, and started swallowing Dexedrine tablets, washed down with gin. (Her selection of Don Giovanni was meant to send a message to Mike, whom she sometimes called “il mio tesoro,” the title of one of its arias: as Mozart’s lyrical opera concludes, the unrepentant libertine Don Giovanni is consigned to hell.)

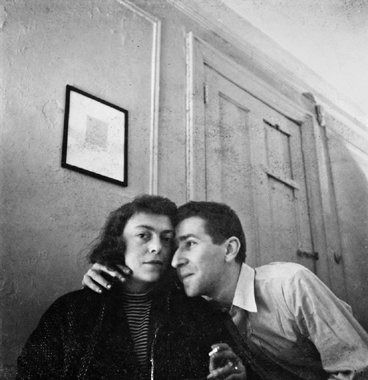

Joan and George on the beach in Springs, 1954 (Illustration credit 8.2)

Joan slept off the overdose, which she experienced as “another kind of blue on a palette.” To botch even her suicide, “a bastard affair,” more absurd than dramatic, was further evidence, she felt, of a “real dull mind.”

Nothing changed. A few days later she wrote Mike,

We have no new beginnings the way you had always hoped and never even clean endings—we just drag ourselves along and if we’re lucky there’s a nice blue line someplace—and I think we’re lucky. I would like to write something very simple to you that would perhaps connect us … Still I’m always meeting you at the station—shit Mike—it’s not much fun being nuts—or living among so many amorphous green trees and ideas—forgive me for being such a schmuck. I’ve loved you so much and it sticks us at two ends of a railroad station—and perhaps it should bore you by this time—my love, I mean—and yet it’s meant much to me—and of course I would do the same thing all over again—miss your fucking enigmatic eyes—te quiero—all colors Juana.

That Saturday the two showed up together at the blowout end-of-the-summer party at the Red House. Cars lined both sides of Montauk Highway, and people thronged house and yard where Elaine had hung the trees with big papier-mâché flowers sprayed with perfume. Even the toilet seat of the outhouse was decorated. The party, Mike later remembered, “was very beautiful and people were very drunk and crawling off into the corners.”

The next day, Joan flew to Chicago because Jimmie was severely ill. Though he seemed “old at last and like a wound,” he turned out to be well enough to say something cruel. Retreating into her parents’ dim, cool, silent apartment, Joan read Mallarmé and felt guilty and “sad about us,” she told Mike, “and frightened.”

On the eve of her departure a week later, she chronicled her summer in a letter to Evans Herman:

I painted so much and destroyed so much—kept thinking of something fantastic like Van Gogh’s Starry Night and came out mostly with my own lack of belief all mirrored and distorted in a cocktail shaker—Christ I’m certainly not a Prince Hamlet but I can gather all the images around me here—heavy carpet, all bells chiming and late-afternoon sunlight on pewter—more realistic than gold but to hell with that … I’ll go to Europe in the winter—I’ll start out all over again without the knowledge of suicide and carry myself with me this time—I wonder if you’ll come with me also—oh I wonder lots of things.

Back in New York City the following day, Joan received word that George was sick and rushed out to Springs. (In the midst of moving and coping with their own unruly boxer and Great Dane, the Braiders were returning Joan’s dog.) The next morning, August 31, 1954, as she hastened to get George to a vet, the most destructive storm in sixteen years, Hurricane Carol, crashed into eastern Long Island. Winds reached one hundred miles an hour. Debris cartwheeled down the streets. Boats hurtled ashore. Roofs blew off houses. The electricity flickered off as power lines collapsed under the weight of falling trees. Paul Brach watched an old apple tree “levitate about six feet, turn on its side, and then exit stage left.” Many artists gathered at the Pollocks’ house, rushing out to help neighbors when they could. At high tide, the ocean raced across Montauk Highway and down Fireplace Road, its dark, dirty waters swirling around cars and flooding homes. Noon abruptly brought dazzling sunshine and sparkling colors. Then the hurricane briefly turned landward again.

At some point that day, Mike stood beside Joan watching Georgica Pond, and then, at the ocean, the two gaped at huge, beautiful, mysterious waves. That morning, according to someone who later heard it from Joan, “she [had] had to risk her life to save the dog … The harrowing experience stayed with her for a very long time.” Joan would tell Irving Sandler, “It was a very devastating experience. Trees fell over. It seemed as if the wrath of God fell upon East Hampton. The hurricane is a ghastly symbol of a frightening period in my life.” It lodged in her memory alongside terrifying Lake Michigan storms, becoming vital feeling material for at least four tumultuous and beautiful paintings based (as Mallarmé famously prescribed) on not the thing, but the effect it produces. As for her summer’s work, Joan later claimed that the duck shed had been demolished and that she had lost many paintings, but Mike recalled that the little building stayed intact.

Before returning to the city, Joan gave George to a farmer. Soon thereafter he was killed by a car. She grieved long and hard.