you are

surrounded by paintings

as in another century you would be wearing lipstick

which you wear at night to be old fashioned, of it!

with it! out!

FRANK O’HARA, “Far From the Porte des Lilas

and the Rue Pergolèse: To Joan Mitchell”

Joan’s social life now revolved around the dimly lit American-style Bar du Dôme, next door to the Café du Dôme, where, night after night, Jean-Paul Riopelle’s table served as a magnet for artists and writers including Sam Francis, Kimber and Gaby Smith, Shirley Goldfarb, Samuel Beckett, Bram van Velde, Sam Szafran, Ruth Francken, Harry Mathews, Pierre Schneider, Shirley Jaffe, Pierre Boudreau, Anne and Hugo Weber, David Budd, Paquerette Villeneuve, and Alberto Giacometti. The barman, Jean-Jacques, automatically kept everyone’s stub, and, as the stragglers prepared to leave, Riopelle, always the profligate Riopelle, would fish out a wad of bills, pay for everything, and leave a huge tip. On quiet late nights when it was just van Velde, Giacometti, Riopelle, Mitchell, and Beckett, the American painter and the Irish writer were apt to talk bleakness and gloom, which so irritated Riopelle that on occasion he bolted. Once, reports Beckett’s biographer Deirdre Bair, Mitchell jumped up and ran after Riopelle and “Beckett followed Mitchell into the door but was too drunk to extricate himself. Round and round he whirled, while Giacometti, like a giant, brooding toad with hooded eyes, sat and watched and said nothing, and while tourists pointed at the poet of nothingness and despair.”

For Joan, years at the Dôme could never measure up to one good night at the Cedar, but at least she still qualified for what Frank O’Hara had wittily dubbed the “promiscuous drunks,” as opposed to their “reformed type” friends who had started settling down. Jane Freilicher had disappointed Frank by moving into a too-comfortable apartment after she married Joe Hazan, and even Grace had wed and left New York. Yet Joan was also quietly instituting certain reforms, allowing herself no more than a single bottle of wine during evenings alone and, knowing that billiards requires a sharp eye and steady hand, coaching herself into moderate drinking when she went out.

As for Joan’s self-presentation, critic Eleanor Munro, writing in ArtNews that November, pointedly excluded her from “a rather handsomely garbed monde of women artists” who had “married and adopted lives of more or less stable rhythm.” Munro found Joan “rangy, occasionally awkward in manner and dress.” In a letter to the editor, Jane Freilicher leaped to her friend’s defense: by setting Joan apart from this monde, she wrote, “Miss Munro seems to imply that Miss Mitchell is not as snappy a dresser as she might be (an implication I protest as positively untrue) and that her life ain’t got rhythm, which is not a nice thing to say about anybody and constitutes an invasion of privacy as well.”

Nonetheless, reading the eyes of Frenchmen acutely aware of women as women and knowing she did often look less than snappy, Joan took pains to fix herself up, wearing lipstick in the evening, patronizing an excellent hairdresser, and purchasing several elegant tailored pantsuits and print dresses. But she still toted the same beat-up handbag, wore baggy unironed shirts, and had a virtual love affair with Paul Jenkins’s old corduroy pants, which were falling apart at the seams. Sitting at a café one day with Riopelle and Giacometti, she cast a jaundiced eye upon Yvonne Hagen, who had walked up in a nutria coat. “Why are you wearing that when you should be wearing a torn raincoat?” she scolded the art critic for the Paris edition of the New York Herald Tribune, a remark Hagen chalked up to the artist’s need for control, especially after Joan herself purchased a $1,500 fur coat from hip New York furrier Jacques Kaplan.

Joan’s penchant for masculine dress was not inconsistent with Riopelle’s pet name for her: Rosa Bonheur, after the painter of the 1863 Horse Fair, which figures among the nineteenth century’s most beloved works of art. As radical in her personal life as she was conventional in her painting, Bonheur affected men’s waistcoats and trousers, smoked, bluntly spoke her mind, and held her own among members of the opposite sex. “Rosa Bonheur” also suggests rose-colored happiness (bonheur). Jean-Paul may have first tossed out the phrase or he may have been responding to comments from Joan triggered by her perception of him as rose pink. Shortly after the two met, back in 1955, she had, without explanation, dropped into a letter to Mike the phrase “La vie en rose commence” (“La vie en rose begins”), shades of synesthesia and of the soulful signature song of chanteuse Edith Piaf.

The course of the Riopelles’ divorce was proving long and tortuous. Prior to 1968, Canada had no federal divorce law, nor did divorce courts or provincial legislation exist in Catholic Quebec, where the Riopelles had wed. In fact, the only way for a Quebecois couple to dissolve a marriage was by private act of the Canadian Parliament. Evidence of adultery (or other grounds for legal separation) had to be submitted to, considered by, and approved by committees of both the Senate and the House of Commons before such an act could be passed. Had these basic facts about the unwieldy Canadian system escaped Jean-Paul’s attention when he blithely informed Joan that his divorce would require three months?

That question popped up more than once in letters among Joan, Sally, and Marion. Six months after legal proceedings got underway, Marion encouraged Joan to believe that Jean-Paul had acted in good faith when he urged her to return to Paris pending his divorce. Another six months passed. In one letter to their mother, Sally rattled on:

I thought that the divorce was being done through London, Canada being part of the United Kingdom and therefore the division of the church and state—ergo what in hell happened to the London Lawyer. However isn’t there something in England about proving adultery and a six year wait? Seems to me the wife and mother [Jean-Paul’s mother, a devout Catholic, opposed the divorce] and the Church might be hand-in-glove with a money wrench? NO? … I don’t really want to be a kill-joy but I don’t see what good a New York boy [Riopelle’s new American lawyer] is going to do for a French Canadian who lives in France—but maybe it all could be worked through a bit of a reverse Marshall plan.

Though Sally liked Jean-Paul because he gave Joan “prods of giggles and won’t take her seriously,” she later added re their mutual ami-in-law:

I think it is just as well that the R.C. church is hanging on forever to their boy because if he stays in the rut of painting-for-money and doesn’t expand in the best Mitchelly manner: “his breath, on a canvas, caught” (Balls [Joan] has always chewed her own cakes even though they have been pretty heavy and stale at times) she will hand him back to the church! I think during that last molten expensive telephone chat we came to some charming agreement like: what difference does marriage make at this point? Now Marion, don’t get your Victorian dander up and seethe and surge. After all WHAT is the Catholic Church to attempt to tell either of your daughters what they may do!

Canadian politics had compelled further delay: in a 1960 move to force debate over a proposal (opposed by the Catholic Church) to transfer authority for divorce to the courts, members of Canada’s New Democratic Party strategically insisted upon detailed study of each petition, thus effectively bringing the process to a standstill.

Jean-Paul and Françoise were finally divorced in France during the summer of 1962, a full four years after the original petition was filed. The cost had mounted so astronomically that Jean-Paul and one of his lawyers joked that the next divorce was being thrown in free of charge. But Jean-Paul had already decided that, crazy as he was about Joan, there would never be a next marriage or divorce, nor would there be a next child.

Joan was to have one or two more abortions. Occasionally she would sigh to some female friend, Well, you have the kids, the husband, the family, I don’t. Her childlessness saddened and embittered her: she felt she was missing one of the primal experiences of life. Yet gradually she resigned herself to it, displacing her need to nurture, support, and teach onto Jean-Paul’s daughters, young artists, and dogs. She never got over Jean-Paul’s perfidy about the marriage, however, pointedly referring to herself as his “mistress,” a word she spit out like a bitter seed. Not only had he failed to live up to his bargain with her, but also he had broken his promise to Marion, made during a 1960 visit to Chicago, to marry Joan. For the duration of their life as a couple, Joan taunted him (calling him “Jimmie” after her father): “So, Jimmie, are ya going to marry me tonight? Are ya going to fuck me? Are ya going to marry me? Huh?”

Art critic Peter Schjeldahl tells this tale:

At a boozy dinner party that I attended in a New York walkup nearly thirty years ago [around 1973], a woman announced that she was getting married. Joan Mitchell, who was there, exploded. How could anyone even think of doing something so bourgeois? The buzzer sounded. It was Mitchell’s longtime lover, the French-Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle. He wanted to speak to her, but he wouldn’t come upstairs. From the landing, she told him in scorching terms to leave her alone. Back at the table, she resumed denouncing the insidiousness of marriage as a trap for free souls. The buzzer again. Another cascade of profanity down the stairwell. I was awed.

Back in 1958, however—the divorce papers had just been filed—Joan operated from a sturdy determination to “work out something decent” with Jean-Paul. The right apartment topped her list of priorities. After months of searching, she ferreted out the closest thing to a loft that Paris could offer: an old top-floor warehouse on the light-industrial rue Frémicourt in the plebeian fifteenth arrondissement. For a fifteen-year lease on 3,500 square feet, the owner wanted $2,000 in key money, plus about $300 a month. Extensive renovations were needed, however, and, as giddy with excitement as Joan was over the prospect of Frémicourt, its potential cost staggered her. Like a kid with her heart set on a toy, she coaxed Eleanor Ward:

give me money—please!! and you’ll have great pictures! If I get this place I’ll never need to sublet and can come and go as I please and I’ll be so happy. The whole idea seems like Santa Claus—no more Schnabel—Jenkins—whomever … Seriously if you could give me some money—any at all I’d love it—I suppose I’m not being businesslike but hell.

Eleanor eventually coughed up a thousand dollars, but Jimmie bankrolled most of the project, giving each of his daughters a fat check that same year. No doubt Jean-Paul kicked in too, but the territorial Miss Mitchell brooked no misunderstandings: if she had to live in his city, she would do so in her apartment: “It makes me pee in my pants when I look at it—and it’s mine,” she crooned.

Joan brings Jean-Paul Riopelle to Chicago to meet Jimmie and Marion, c. 1960. (Illustration credit 11.1)

Polish-born architect and artist Piotr Kowalski was hired to design the living room, kitchen, studio, and bedroom, using angled skylights, gorgeous old wood beams, and hardwood floors, while Jean-Paul’s buddy, Greek American artist and Picasso look-alike Alex Costa, supervised the construction crew, literally a bunch of clowns (Rex, Quito, and Dédé). Hence the zany trapeze in Joan’s studio. Or maybe Jean-Paul cooked up the trapeze idea. In any case, he invested demonic energy in designing witty saloon-style swinging doors for Joan’s studio, building moveable walls for her paintings, and creating small niches to display sculpture in the living room, which would also have a rustic fireplace. He was all the more enthusiastic since the building’s ground floor housed an automobile repair shop where he could keep part of his car collection which, at various times, counted a Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, Duesenberg, Aston Martin, Bristol, Fiat, and Morgan, not to mention his cherished Bugattis.

Only weeks before their planned move into this dream apartment, however, the couple’s life blew to smithereens when Joan learned that a young gallery assistant named Yvonne Fravelo was pregnant by Jean-Paul and planned to have the baby. Livid with pain and rage, she reacted like a wounded animal. Coincidentally, she had a plane ticket to New York (for a short visit timed to coincide with Paul Jenkins’s to Paris), so she used it: “I am always tying up / and then deciding to depart.”

A week or two later, on April 10, Jean-Paul in Paris answered a sour letter from Joan in New York:

Joan, Chérie, I’m at the Falstaff with an old beefsteak and much remorse that I let you leave. This morning I received your letter which is not very encouraging on the subject of your return. I understand that this is probably even more difficult for you, and I hope everything takes a turn for the better … The studio is coming along. Poor Alex is having a hell of a time with the floor … I really have the impression that you will be able to live in this super-palace very soon. Ten days, two weeks, I invite you, and, if you don’t come, I’ll smash everything.

Joan didn’t budge. Jean-Paul smashed nothing.

More letters flew across the Atlantic:

Your last letter seems so pessimistic [wrote Jean-Paul]. Regarding the children [his daughters], I’ve taken no immediate decision, yet, the more I think about it, the more I believe that everything will work out with you, my love, and you have no reason to accuse yourself because without you I can no longer do anything, as you well know, just remember. I want the divorce to happen. When will we be together? You tell me you can be free after May 18th. Wouldn’t it be best that you come? So, breathe deeply—as JM always says—because “tout va très bien, Madame la Marquise.”

At one point, Riopelle proposed they flee the temptations of Parisby going halves with Georges and Marguerite Duthuit on the fifteenth-century Château de Rozay, along the banks of the Cher, but, in the end, he flew to New York, stayed two months, and charmed Joan back to Paris.

Before leaving France, Jean-Paul had arranged to charter the luxury yacht Fantasia, captained by an old campaigner from the Queen’s Navy, for a Mediterranean cruise en famille that would give Joan the perfect opportunity to get acquainted with her “stepdaughters”-to-be. True to pattern, however, the promised “two sailors, two masts, two cabins, two children, two lovers, you and me” multiplied into nine travelers and myriad complications. His mentor, Georges Duthuit, wife Marguerite (née Matisse), and their son Claude accompanied Joan, Jean-Paul, Yseult, and Sylvie on an early-August flight to Athens, from where they sailed to Istanbul, toured the city, then again weighed anchor. The voyage was gorgeous, unreal, and exhausting: not only did the Duthuits have to be entertained but also, Joan felt, Yseult and Sylvie had to be instructed in Greek history and English in the morning (she shopped for textbooks in Athens) and swimming in the afternoon.

As the Fantasia approached Mount Athos in the northern Aegean, the travelers’ anticipation stirred. A semiautonomous theocracy, Mount Athos, or Hagion Oros, is a center of Eastern Orthodox monasticism comprising twenty monasteries set upon a dusty, splendidly rugged peninsula and housing some of the world’s finest Byzantine and post-Byzantine art. Very few outsiders were allowed access to this spiritual center, but Duthuit’s status as a specialist in Byzantine art with important connections in Athens had opened its doors. They dropped anchor, dressed for the visit, and eagerly awaited the arrival of the guide who was to take them ashore.

No one had dared tell Joan, however, that, for over nine hundred years, not a single woman had been permitted to set foot upon the Holy Mountain. Even female animals were banned, save chickens, whose eggs are used in the tempera paint needed for icons. The delicate task of announcing these facts fell to their guide. As feared, Joan flew into frenzied, ear-splitting rage over this denial of the opportunity to see great art solely because she was a woman, but, in the end, she had no choice but to cool her heels on the boat with the other females as the males paid their visit.

A black mood then descended upon the Fantasia. Joan snapped and snarled, the boat felt cramped, the drinking turned ugly. Before the voyage was out, Riopelle had clashed furiously with Duthuit, and this key player in the French art world had gathered up his wife and son and stalked off at the following port. The break was definitive.

Nonetheless, September found Jean-Paul and Joan once again yachting, now with his New York dealer Pierre Matisse (Marguerite Duthuit’s half brother) and wife Patricia. A couple of weeks after the two lovers had settled at last into Frémicourt, Jean-Paul’s son, Yann Fravelo-Riopelle, was born in Brittany. Joan knew there was no pure joy, except perhaps in painting and looking: that winter, Paris was “lovely with snow—like coconut.”

Joan with her Skye terriers, Isabelle and Bertie, in her Frémicourt studio, c. 1960 (Illustration credit 11.2)

Always up by six or six thirty a.m., Jean-Paul would brew a pot of coffee and gulp down a cup before tearing off to his studio, while Joan slept in, having often painted most of the night. Groggy and silent when she did rise, she would sit reading, sipping from a big cup, and sending curls of cigarette smoke toward the ceiling, then rev up by walking her trio of adored Skye terriers—Idée, Isabelle, and Ibertelle (Bertie), recent gifts from Patricia Matisse.

Virtually every day the couple entertained at lunch, sometimes one or two guests, often a gang. Regulars included Sam Beckett, John Ashbery, reporter Pierre Martory, writer/critics Pierre Schneider and Patrick Waldberg, Riopelle’s French dealers Jacques Dubourg and Max Clarac-Sérou, sculptors Marc Berlet and Mario Garcia, painters David Budd, Zao Wou-ki, Zuka Mitelberg, and Anne and Hugo Weber, plus a mix of clowns, musicians, Formula One racers, traveling Canadians and Americans, and assorted strays. The living room, decorated with Riopelle paintings, Jimmie Mitchell drawings, and riotous philodendra, would be buzzing by the time their host popped through the door, raising a ruckus with his robust energy and ebullient laugh. The hairy little Skyes jostled underfoot. Prepared and served by Joan’s maid, Paulette, their lunches ran to beef or horse steak, mashed potatoes, and salad, washed down by copious quantities of pastis, wine, and brandy. Jean-Paul would dish up shaggy dog stories, and Joan would prove, by turns, tough and judgmental, flirty and girlish, or bald and provocative. “Eh, Coco,” one might make out over the bilingual din, “you know nothing about painting!” If Joan found people stupid or sluggish, she’d zing them. If she was bored, she’d make trouble, sometimes with casual cruelty: “So how’s your fucking mother and her fucking cancer?” she inquired of one young man who had just flown to Paris to be with his dying parent. Wont to home in on a single guest, Joan would charm out the secrets of his or her childhood, aspirations, or current feud or love affair, as she sipped pastis and reflected genuine caring in her tired brown eyes. When the spirit moved, however, she would turn around and mortify her interlocutor by broadcasting to the entire room these indiscretions from a liquor-loosened tongue. One should be completely honest, Joan insisted, there was nothing to be ashamed of!

After her guests departed, Joan might lend a hand to Paulette with the dishes or housework. (She was finicky about keeping ashtrays emptied, dog bowls clean, and food traps immaculate.) Or she might head for her studio to check her colors in daylight. Or sit down to write two or three of her gossipy, stream-of-consciousness letters. In that era, a transatlantic call was still an event and Joan remained cost-conscious, yet, from time to time, she would pick up the phone and natter on to New York, Chicago, or Santa Barbara. She also handled the household bills (Jean-Paul never in his life had a checkbook), plus chores like taking to the dry cleaners the suits her companion wore day in and day out. “You know the only reason I screw Rip [one of her nicknames for Riopelle],” she joked, “is because it’s the way I get him to change his clothes. I put his old suit in a bag and make him wear a new one.” But hand the man a fresh suit and he’d grunt, “Did you get my boots? Where are my boots!”

Rarely did the couple attend plays, concerts, films, or even art openings, except those of close friends (Riopelle detested schedules and obligations), instead devoting their evenings to the brasseries and watering holes of Montparnasse. These included the new Rosebud, an intimate rue Delambre bar where the style of New York blended with the atmosphere of Paris, a Coltrane record softly spinning as Ionesco or Truffaut sipped kir at a corner table. The Rosebud’s famous chili con carne became favorite supper fare, along with the bifteck at the Falstaff, the seafood platters at La Coupole, and the lamb curry and omelettes aux fines herbes at the Closerie des Lilas. Mostly they drank.

Though the two shunned public displays of affection, their complicity and mutual happiness remained obvious. “Riopelle was very much in love with Joan, wanted her, needed her,” reports one of the tribe of artists and writers with whom they partied. Sparring and teasing—as one day when she couldn’t shift the gears properly in one of his sports cars—were part of the game. So too were wild, hysterical scenes. Once Joan silenced the Café de Flore by yowling, “Are you going to fuck me tonight, REM-BRANDT?” Another time she stunned the crowd at the Dôme by acting upon her annoyance when Jean-Paul started counting out bills to pay everyone’s tab for the thousandth time: lunging for the cash, Joan ripped it up and hurled the bits into the air like confetti.

As time passed, Riopelle’s old friend, Suzanne Viau, observed that sometimes

[Joan] was the mean parent, sometimes [Jean-Paul] was. They lived essentially in fight-and-make-up mode. One could see their brawls as a sort of sexual dance leading up to mating. I remember one dinner. He was harassing her. She was blubbering, the box of Kleenex and everything. Then, all of a sudden, the wind shifted. In the car that was taking us home, I almost felt like one person too many. “Jean-Paul, you’re such a baby,” she was cooing. They had completely put it behind them.

In truth, Jean-Paul’s rampant infidelities and Joan’s jealousies had begun corroding their relationship. The virile artist had always had opportunities galore for sex, had always taken advantage of them, and saw no reason to change now. “Riopelle had a huge number of mistresses,” remembers Marc Berlet, “really huge!” Painfully aware that there was “nothing in a skirt Riopelle didn’t want,” Joan appeared to know all about his affairs with other women, whether his casual trysts or his long and vital intimacy with the accomplished, intelligent, and vivacious French sculptor Roseline Granet, eleven years younger than Joan and stiff competition indeed. In her most quarrelsome cigarette-cured voice, Joan would bait Jean-Paul about Roseline until the two were slinging drinks into each other’s faces and, liquor fueling their fury, he was smacking her and she was smacking back.

Other times Riopelle’s displeasure about Joan and Sam Beckett propelled their brawls. His own dalliances notwithstanding, the Canadian was determined to own Joan one hundred percent: no other man was going to touch her. Thus all his bristles shot up at the thought of her intimacy with the famous writer and intellectual.

Not until years later did Joan reveal, and then only to a few friends, what many had long guessed: that she and Sam, himself an extremely private man, had been lovers. Critic Pierre Schneider puts a fine point on the writer’s feelings, noting that Beckett was “extremely taken by Joan and petrified by a kind of admiration.” (Beckett lived with pianist Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil, whom he quietly married in 1961 for legal and financial reasons, but the two led mostly separate lives.)

In the midst of a tribal Montparnasse evening, Joan and Sam would often disappear for two or three hours. To Joan’s glee, “Rip would get so jealous. Sam and I’d go off and we’d have our little thing, and we’d go back to the Closerie des Lilas and Riopelle would be so upset.” One night at the Rosebud, Riopelle’s verbal brickbats prompted the usually tolerant Beckett to stand up and change tables and Mitchell to vent her fury upon her companion. Other nights he publicly took out his anger on her. Once the same trio had just left the Rosebud, along with John Ashbery, when Jean-Paul seized Joan by her shirt and started slamming her into parked cars. At least once he found dark humor in the affair. Stopping one day to have a word with their concierge, he spotted a coffin standing upright alongside the trash cans. The concierge’s husband had died, and the coffin had been delivered by the mortuary. The artist continued upstairs. Bounding into their apartment, he shouted, “Joan! Joan! Beckett is waiting for you at the concierge’s,” whereupon she rushed downstairs to discover only the Beckettian mise en scène.

Other incidents too proved worthy of the theater of the absurd. One late night Beckett was hastening from Frémicourt before Riopelle returned when, at the bottom of the stairs, he realized that the old-fashioned porte cochère of the body shop, the only way out, was locked. So he climbed up its iron bars but fell backward, landing in an oil pit, from which he emerged looking very much the existentialist character. The next day his sides ached. It turned out he’d broken a couple of ribs.

In speaking of Joan, Beckett made little distinction between the person and the painting; for Joan too, the art of this literary figure worthy of those she had known as a child played a vital role in their relationship. She had, of course, read much of his oeuvre but most deeply loved his 1959 radio playlet Embers.

Set on Killiney Beach on the Irish Sea—Sam’s Lake Michigan—near the writer’s childhood home, Embers weaves present with past, form with formlessness, silence with voice, music, and noise. Its sole character, Henry, conjures hallucinatory dialogues with his drowned father (who may have committed suicide) and his daughter’s mother, all the while attempting to override the incessant, radio-static-like clash of the sea. (Scholar Marjorie Perloff labels Embers “acoustic art.”) Henry also tells himself a story about a man who has summoned his doctor for obscure but hideously troubling reasons. Beckett writes, “not a sound, fire dying, white beam from window, ghastly scene, wishes to God he hadn’t come, no good, fire out, bitter cold, great trouble, white world, not a sound, no good. (Pause.) No good. (Pause.)” The writer ventures no further down the road to description, a refusal Joan viewed as parallel to that of a good painter: “If something is green you know it’s green, but he doesn’t say it’s green.” The pair conceived of a limited edition of Embers that would marry Beckett’s words with Mitchell’s gouaches. She did about fifty, then decided that Embers was perfect without them.

Physically, their relationship was what it was. True to his pattern, the writer had to be prodded into sex. One night after he and Joan had checked into a hotel, Sam consumed his best energies in fumbling around under the bed in search of his misplaced dental bridge. Another time, at the Rosebud, he was overheard to advise her, “Stick to Riopelle, he can fuck and I can’t.”

As the 1950s waned, Joan’s paintings had swung between thinnish-looking, levitating St. Vitus’s dances of reds, greens, yellows, blues, and blacks, indebted to Pollock, on one hand, and, on the other, vigorous, fleshy fists of paint: blue blacks, greens, mustard yellows, and opaque whites with becalmed edges, or not. Now she delivered a radiant crayon box of reds, blues, oranges, olives, violets, and yellows, shooting across a distinctly horizontal canvas as if a fierce wind had ripped open one of the slab-built pictures. Then came the splendidly disorienting and panoramic County Clare, at once opulent and spare, its light like that preceding March squalls. Scraps of mossy green, mongrel ochre, and white tatter its edges while tiered zones of white and dried oxblood, one ambushed by gold ochre, brew at near center. Dazzling blue-lined scud throws the eye into spatial confusion. Red skitters through. Brushed, clotted, smeared, and runneled with pigment, County Clare strikingly incarnates, as the artist put it, what landscape left her with. Her title weaves in after-the-fact associations: the Irish County Clare, the French word “clair” (meaning luminous, light in color, transparent, easily understood), the English romantic peasant poet John Clare, author of the melancholy “I Am.”

The spring of 1960 found Joan “working like a little beaver” on her first French show for dealer Larry Rubin’s Galerie Neufville that April and her first Italian show for the Galleria dell’Ariete in Milan, owned by Rubin’s business partner, Beatrice Monti, in May. Once those two were behind her, she would turn her attention to her next show at the Stable, which she wanted to paint in New York. She broached, but Jean-Paul at first resisted, the idea of summering on Long Island. No sooner had he relented than their three-month sojourn ballooned into a vast, unwieldy operation enlisting their young artist friends Marc Berlet and Mario Garcia.

Berlet departed first, aboard the Liberté, with Joan’s trio of dogs, plus a racing car fresh from Le Mans that Jean-Paul hoped to drive semiprofessionally in the States. Then Riopelle flew to Montreal to collect Yseult and Sylvie before rendezvousing with Joan and Mario in Manhattan, where Frank O’Hara and Joe LeSueur swept them back into the art world with a lavish cocktail soirée. Two or three days later, the Parisians occupied a pair of houses at Hampton Waters, Barney’s Three-Mile Harbor real estate venture, where they promptly fell into familiar patterns, Jean-Paul zooming off at dawn in a red Jaguar XK convertible to his studio in Bridgehampton, Joan creeping out late mornings to breakfast on cigarettes and Bloody Marys. Over long talky lunches with Joan’s old pals, the two sloshed down bucketsful of negronis. Then it would be Joan’s turn to head to her studio, a nearby barn. Or she might drive into town in her borrowed ’56 Buick to shop for the dinners she cooked for the kids. An attentive stepmother, she arranged for the girls to take riding and swimming lessons and once organized a day of deep-sea fishing off Montauk with Wilfred Zogbaum and his twelve-year-son Rufus in Zog’s boat.

Joan, of course, knew vast numbers of people, many of whom were partying longer and harder than ever that dipsomaniacal summer. The Zogbaums (Zog had remarried) hosted a boozy brunch, Barney threw a huge lawn party, and Bill de Kooning and his lover Ruth Kligman invited everyone, including the collectors and millionaires the scene now embraced, to a bash at their Southampton rental—only Bill himself vanished before it began. Except with Francophiles like Norm, Frank, and Zog, Jean-Paul seemed out of his element. Once, at Larry Rivers’s house, as hordes of guests drunkenly laughed and screamed, he curled up on the living-room floor and fell asleep. When Joan buried herself with Mike in her studio, Jean-Paul acted out: one morning, she showed up with a black eye half concealed behind her dark glasses. Marc considered her “the Billie Holiday of Abstract Expressionist painters”: “I love my man though he treats me so bad. That was Joan: masochistic.” Goldberg too now drove a Bugatti, but Riopelle snapped his fingers at Mike’s car: it was the wrong kind of Bugatti. So it went between New York and Paris: in effect, the Americans snubbed Riopelle, who spoke spotty English, did not share their formative history, and incarnated the scorned School of Paris.

Meanwhile, Joan’s New York was fast changing. The morning after had dawned upon Abstract Expressionism, revealing frayed friendships and a waning feeling of family. The Cedar ruined by its own popularity, the remnants of the old crowd had migrated to the unassuming Dillon’s at Twelfth Street and University Place, but it wasn’t the same. Hartigan had ensconced herself in Baltimore, Pollock was dead. For the first time, leaving the city made sense to some. Why not? With the staid Eisenhower administration drawing to a close, the national mood favored new beginnings. Artists were traveling or taking visiting professorships. Bill de Kooning talked restlessly of moving to Springs.

Meanwhile, curators, critics, and art historians had begun considering the fifties retrospectively, collectively borrowing a phrase from the Jewish Museum’s 1957 New York School: Second Generation exhibition to label the work of Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, Alfred Leslie, Michael Goldberg, Norman Bluhm, Jane Freilicher, Larry Rivers, and others “second generation Abstract Expressionist.” Informed by Greenbergian logic, according to which painting has the historical purpose of advancing modernism toward formal purity, the term not only adverts to the American shibboleth of progress but also assumes a homogeneous convention-shattering “first generation.”

Not alone in hotly contesting such premises, Joan rejected, first, the concept of a first-generation breakthrough, pointing out that World War II had churned up everything, painting included. Moreover, she insisted that the artists’ lived experience had had absolutely nothing to do with generations. Everyone, whether age twenty or sixty, had been painting at the same time. Everyone, whether age twenty or sixty, had been making the same revolution. Besides, the art world inconsistently applied labels “first” and “second,” not to mention that “Abstract Expressionism” itself remained a misnomer, New York School painting having to do with attitude and place, not style. Wrong, countered its detractors, it had degenerated into stale imitable manner.

The decline of Abstract Expressionism coincided with the rise of Color Field painting and Pop Art. In 1961, Andy Warhol would paint Campbell’s Soup cans, Roy Lichtenstein depict, comic-strip style, a girl holding a beach ball over her head, and Claes Oldenburg rent an East Second Street storefront where he sold crude painted plaster models of consumer goods. The following year, the prestigious Sidney Janis Gallery pushed New York School painting offstage to bring Pop front and center with New Realists, an exhibition that conjoined French Nouveaux Réalistes with new American Pop stars including Lichtenstein, Warhol, Robert Indiana, Wayne Thiebaud, and George Segal. In response, Philip Guston, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Adolph Gottlieb severed their affiliations with Janis. Marketed as part of the same consumer culture that was its subject, Pop Art was about to explode into an unprecedented frenzy of collecting, dealing, showing, publishing, and self-promoting.

Joan detested not only isms but also the idea that one kind of art had to wipe out another. (Rather than raze Impressionism, ArtNews editor Tom Hess reminded his readers, Cézanne had used it as a point of departure. And Willem de Kooning had long proceeded by reinventing European art.) In truth, Joan could not abide Pop Art—“all money and no cathedral”—because of its passionlessness, superficiality, indifference to paint as such, and glorification of the mass culture she ignored. In contrast, she respected the complex, cerebral work of Jasper Johns: at Bill Berkson’s 1961 Christmas party, the two would meet and together dance the twist (while Helen Frankenthaler and her husband, Robert Motherwell, she cattily reported to Mike, sat primly on a sofa).

In the new culture of irony, the emotional sincerity of Joan Mitchell, unreconstructed New York School painter, felt old-fashioned and slightly embarrassing. By continuing to pursue what she called “visual painting,” some thought, Joan was trying to stay at the party after the lights had come on. She began spouting the phrase “pop art, op art, slop art, and flop art.” She practiced, she said, “slop and flop.”

Yet her art remained limber and fresh. Inextricable from her authentic self, “visual painting” was almost a neurobiological need: to work in any other manner would amount to opportunistic dishonesty. While not unaware of her ego involvement in a successful career or of her options for painting saleable work, Joan militantly refused to follow trends in order to get shows. (Luckily she had the financial means to do so.) For this hard-nosed closet Romantic, the visionary energy and unbridled joy that stemmed from truth to oneself and intimacy with nature and paint put to shame the politics of art.

Although Joan sank from view in New York as much because she had moved to Paris as because Pop Art held sway, she started talking of having been kicked out of the art world. By and large, her reviews continued positive, but there were far fewer of them, and far fewer shows. Deprived of institutional and critical support, she undertook a kind of high-wire act without the crowd—continuing to hold herself to the standard of art of the highest intensity, greatest risk, and loftiest ambition.

Though privately bitter, she would rather die than complain. One rose above it, waited it out. The full truth be told, the romantic in her at times enjoyed the role of neglected, misunderstood artist, and the realist got by on the thought that nothing worse could happen to her career. “There’ll always be painters around,” she once assured John Ashbery, meaning “real painters.” “It’ll take more than Pop or Op to discourage them—they’ve never been encouraged anyway. So we’re back where we started from.”

Back in Manhattan that November following her summer on Long Island, Joan made her first professional foray into printmaking at Tibor Press, which was producing a four-volume boxed-set limited-edition book based in collaborations between New York School poets and painters.

Paired with Ashbery (the others were O’Hara/Goldberg, Schuyler/Hartigan, and Koch/Leslie), she proceeded from the feelings aroused in her by Ashbery’s The Poems, which shared with her painting a direct absorbing of the world without perspective or logic. Using crayon, she worked directly on silkscreen, then, wanting crisp as well as fuzzy edges, turned to tusche, an inky liquid, for which she fashioned a brush from a broken wooden tongue depressor. She proceeded to apply the tusche to Mylar, from which her imagery was transferred photographically. The collaboration proved fun, the result a modest artistic triumph.

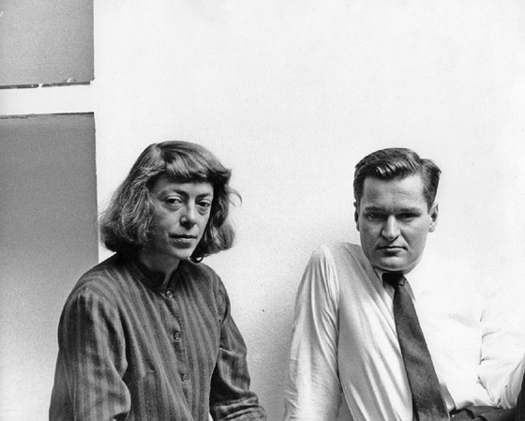

With poet John Ashbery, 1963 (Illustration credit 11.3)

Meanwhile her oils continued to evince Joan’s total involvement in the act of painting: complex and alive, they could not be more different from cool, hard-edged Pop. Take that, Pop Art! Joan seems to say. And that! This is what real painting looks like. (“To paint,” she once declared, “is to know how to resist paint.”) As delectable as they are raw, her paintings court chaos with their sweeps of disrupted syntax, surpassing the viewer’s ability to process them in a conscious way. Deep greens, orange reds or persimmons, and cerulean blues—colors she used over and over again—well up into patchy cumuli suspended in thinned whitish washes agitated by wisps, Xs, tattings, and cascading drips of pigment. Everything about these luscious chromatic canvases speaks of the artist’s all-consuming lover’s quarrel with oils. Paint meets canvas in every conceivable manner: slathered, swiped, dry-brushed, splattered, dribbled, wiped with rags into filminess, smeared with fingers, slapped from a brush, smashed from the tube, affixed like a wad of gum—a glorious visual glossolalia.

The following March, Riopelle took possession of the Serica as payment from Pierre Matisse. A forty-seven-foot Bermuda cutter of Sparkman Stephens design, this superbly crafted yacht boasted a wooden hull, teak deck, and mahogany interior. Having berthed it near Cannes, the artist then rented La Bergerie, a villa with servants in a wealthy enclave at Cap d’Antibes where he and Joan spent the summer with Yseult and Sylvie, who arrived from Canada that June. After the girls left, three months later, and summer stretched into autumn and winter, the couple kept the house and continued to spend a great deal of time in the Midi. Joan wrote her mother,

Joan and “Rip”—crazy about each other! c. 1963 (Illustration credit 11.4)

Everything is closed and the sea quite nice and bleak. When it rains, which it’s not supposed to do, I wear a hat, because my studio leaks, and a yellow macintosh. At noon we still eat on the terrace in the winter sun—at night t.v.—and innumerable books on the sea. We’re cleaning the hull on the boat—endless job—changing some of the interior which is rather fun—like a jigsaw puzzle—everything has to fit and be useful—J.P.’s idea (vague but real) is to sail across the Atlantic—season for it is Dec. to May … would take about 21 days from Gibraltar. Perhaps if we plan it enough we won’t really have to do it.

They never crossed the Atlantic, but they did devote weeks and months to plying the Mediterranean and the Adriatic. While Joan had always equated sailing with sunbathing at sea, Jean-Paul loved packing on speed and sweeping along, spinnaker bulging and porpoises chasing behind. Once the pair and their two-man crew fell fortune to three days of weather so heavy they had to don safety harnesses to change the sails, and they expected the mast to snap at any moment. Jean-Paul was in heaven, but Joan panicked and, for once, couldn’t get even the cognac down. In truth, she didn’t much like sailing. Nerves often sent her below, where she shut herself up and read mysteries. Still, she loved the elasticity of time at sea, the boat’s indifference to its passengers, and the sensation of lying open—sun drenched, rain pummeled, storm flailed, moon bathed—to water and sky in their every light, color, and mood.

And, resolved to share her man’s passions, she threw herself into sailing, going so far as to take short trips alone with René, the sailor they hired on retainer, in order to hone her skills. (Her determination to make the relationship work also led to crouching behind bales of hay as Jean-Paul whooshed by in his homebuilt racer Gueule de Bois, taking skiing lessons in the French Alps, repeatedly enduring the Twenty-four Hours of Le Mans, going duck and pheasant hunting, and once skinning, butchering, and marinating a wild boar her companion had shot.) When the two were happy, as by all appearances they were in Cap d’Antibes, they were intensely happy. But they spoke different languages: she’d say, “Look!” and he’d say, “Let’s go!”

In terms of exposure and sales, the very early 1960s were good times for Joan Mitchell’s career. Besides her April 1961 show at the Stable, now on East Seventy-third Street, and a cover story in November’s ArtNews featuring the billowing Skyes (the occasion was her ten-year retrospective at the gallery of Southern Illinois University), Joan had her first solo show in Chicago and first solo show on the West Coast. Between July 1, 1960, and December 31, 1962, Eleanor Ward rang up $42,968 in Mitchell sales, of which Joan earned $32,358. But these numbers reflect the catching up of middle-class, corporate, and provincial tastes, as opposed to any growing interest in New York.

In the spring of 1962, the Galerie Dubourg on the Right Bank and the Galerie Lawrence on the Left jointly exhibited Joan’s recent paintings. Pierre Schneider wrote a beautiful essay, Jean-Paul worked on the installations, and a crowd of Joan’s friends, including Barney, Zuka, Paul, Mike, Beckett, Norm, her sister Sally, and her brother-in-law Newt, turned out for her opening and celebratory dinner. “The gay gigglers sat at one end [of the long table], the egocentric nonsmilers sat at the other, and Joan [pretty in a new blue suit] and Dubourg sat in the middle,” Sally reported to their mother. Dubourg not only sold out but also laid big plans for future shows. He was old, however, and, in any case, more hail fellow than effective dealer. Nor was the Galerie Dubourg, upstairs in a commercial building, anything spectacular. When his projects came to naught, Joan understood. But when Galerie Lawrence dropped her, she got hopping mad. Its owner, Larry Rubin, had promised to buy $10,000 worth of work annually, an arrangement that lasted one year. Then, as Joan put it, Rubin “kicked me out” on the advice of his new art adviser, critic Clement Greenberg: “Get rid of that gestural horror.” Critics were bottom-feeders, in Joan’s opinion, and the condescending Greenberg’s role in steering galleries and collectors away from her work never ceased to make her blood boil, though she was cagey about when and where she said so. Publicly, she was elliptical or mute; privately, she filleted the still-powerful critic.

Barney Rosset and Samuel Beckett arrive at one of Joan’s shows in Paris, early 1960s. (Illustration credit 11.5)

Explosive, radiant, and atomized, as delicate and wild as sea spray, the paintings Joan was showing—including Couscous, Bonhomme de Bois, Frémicourt, and the panoramic Grandes Carrières—shuttled between New York swagger and European pastoralism. Pigment flying upward and outward, the artist had snarled up browns, dark greens, blues, viridians, and, most strikingly, pink corals, roses, and orchids, amid whites helter-skelter with flecks and veiled cascades of drips. Indebted to Bach (whose music she had been playing almost exclusively as she worked) and to memories of feelings stirred by furious tides, inconstant skies, tender meetings of water and light, the paintings recall Rilke’s lines in “Bowl of Roses”:

with its wind and rain and springtime’s patience

and guilt and restlessness and obscure fate

and the darkness of evening earth and even

the changing clouds, coming and going,

even the vague intercession of distant stars,

into a handful of inner life.

Frenzied and luxuriant filigrees of pinks and greens pulled to the edge of chaos, the paintings of the early 1960s admit a distinctly European color sensibility and sense of beauty also reminiscent of the rapturous late seascapes of British Romantic painter J. M. W. Turner. Critic Holland Cotter sees in them eighteenth-century French Rococo painter Fragonard’s “vistas of billowing trees and clouds, and their vignettes of amorous pursuit and encounter [blown by Mitchell]—ecstatically, furiously and repeatedly—to smithereens.” And Pierre Schneider evokes “Titian in the way in which [Mitchell’s] brush was able to do anything with utter naturalness. The moments when everything falls into place are incredible. Panic, chaos, and anguish overcome. They are sacred moments.” In his catalog essay for the painter’s 1962 show, Schneider also pronounces a Mitchell canvas “the story of Daphne”—the Greek nymph pursued by Apollo—“a being seized by panic, gasping for breath … who at the moment her strength fails escapes by transforming herself into a tree.”

In Golfe-Juan (where Jean-Paul now berthed the Serica) a few days after her opening, Joan received a telegram announcing the death of Franz Kline. Afflicted with a rheumatic heart, Kline had suffered a series of heart attacks, the last one fatal. Deeply shaken by the loss of this exemplary artist and generous spirit who personified her New York, Joan arranged for delivery of a big bouquet of black and white tulips for his memorial service. Then the Serica weighed anchor for Venice via Corsica and soon hurtled into a squall. Thunder crashed, the boat leaked, Joan was petrified. But she reassured herself: “Well, there’s Kline upstairs mixing drinks.”

On May 23, the day New York artists gathered to pay tribute to the beloved painter on what would have been his fifty-second birthday, Joan was in Corsica. Later she flew to Venice, joining Riopelle, who had sailed around Italy with friends. He was widely favored to win the top prize for painting at that year’s Venice Biennale, and Giacometti, the top prize for sculpture. Surrounded by friends, they had a blast in Venice—where swarms of dealers, collectors, reporters, and artists sipped Bellinis at Harry’s Bar and compulsively snapped pictures of each other on gondolas—though Joan responded less to the art than to the watery city with its fabulous colors. Giacometti indeed won the top sculpture prize, but the judges passed over Riopelle for the top painting prize, awarding him instead, along with a Danish painter, the UNESCO Prize, de facto second place. Disappointment briefly clouded the Riopelle camp, yet his (and Giacometti’s) dealer, Pierre Matisse, who had joined them in Venice, remained loyal and supportive, and Riopelle himself appeared to shrug off the loss.

With or without the Venice prize, he cut a wide swath. In 1963 he became the youngest artist ever to have a retrospective at the National Gallery in Ottawa (the exhibition then traveled to Montreal, Toronto, and Washington, D.C.), and he won a major commission for Toronto’s Pearson Airport. Canada’s pride in its international art star helped drive his career, but his market-hardy work also sold briskly to individuals at splashy gallery shows in Montreal, London, Paris, New York, and Lausanne. Joan, on the other hand, did not have a single solo exhibition in 1963. Nor in 1964. She would finish her paintings, let them dry, roll them up, and store them in a little alcove above the kitchen.

After the Biennale, Jean-Paul, Joan, Yseult, Sylvie, and several friends sailed the Yugoslav coast alongside Pierre and Patricia Matisse on their yacht Old Fox. A cool eminence in the international art world, Pierre reigned over an elegant Fifty-seventh Street gallery that represented leading European modernists of the highest stature, including Giacometti, Miró, Balthus, Dubuffet, Chagall, Tanguy, and Pierre’s father, Henri Matisse. Painter Loren MacIver was one of the few women and few Americans in his stable. Matisse took a long view of his artists, ignoring the vicissitudes of the market as he shaped their careers.

The gallerist was married to the wealthy ex of painter Roberto Matta, Patricia Kane Matisse, a “little monster” who took seriously only what she felt like taking seriously and was forever trading barbed remarks with Joan in what the artist elliptically called “a special relationship.” Meanwhile Joan was busy laying siege to Pierre because—stoic as she was about not getting shows, scornful as she was of artists who slavered with ambition, adamant as she was that never would she share a dealer with Riopelle—she wanted in the worst way to be represented by Matisse’s classy gallery based in art values, not money or trends. She made passes at Pierre, she did (in Marc Berlet’s words) “terrible things” to try to persuade him to represent her. But Pierre, who couldn’t see the power of her work, was “like a stone.”

Joan found herself in the role of artist-wife of a Great Artist, a role not unlike those once played by Lee Krasner vis-à-vis Jackson Pollock or Elaine de Kooning vis-à-vis Willem de Kooning. (People assumed Joan and Jean-Paul were married.) Certainly, she had easy access to all the major players, yet socializing with the powerful rarely translated into professional advantage. For one thing, France was acutely sexist (less than twenty percent of Paris exhibitions presented work by women, and only twelve percent of the work in French national collections was by women), and the international art set, mostly male, automatically put Joan as artist in a backseat to Joan as wife. When renowned Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh arrived to make a portrait of Riopelle as part of a series of major figures in the arts, he posed Jean-Paul in her studio, but no one brought up the idea of a portrait of Mitchell. Her job was to entertain the photographer and his wife. And, for years, Joan played hostess to “dear old Gimpel”—Peter Gimpel, Jean-Paul’s London dealer from Gimpel and Sons—during which time Gimpel purchased a total of five small Mitchells, more or less as a courtesy. (In the end, he did offer Joan a show, which never occurred, probably due to scheduling conflicts.)

If Jean-Paul and Joan competed, they also nurtured each other, helping to plan each other’s shows and giving thoughtful advice on materials, contracts, prices, and art politics. Nonetheless, the relationship was asymmetrical: with his career sailing high and hers limping along, it cost him little to help her. At art events where he was hounded by admirers, she would sit smoking, sipping white wine, and chatting. Remembering the Mount Athos episode, she acidulously labeled herself and her own artist friends “just us chickens”—as opposed to “the big rooster,” Rip.

Yet she yearned for things to be right between them, and at times, they were. “J.P. is sweetie pie and almost divorced,” she cheerfully informed Eleanor Ward that spring, “and sometimes there are whole days when I don’t drink at all.” Five months later, however, Frank O’Hara and Bill Berkson, visiting Paris, found Joan in a different frame of mind: “I think the happiest days of my life were when I was going to a chiropractor,” she told them. “Isn’t that the most depressing thing you’ve ever heard?”

With Jimmie’s health failing, Joan had begun traveling to Chicago twice a year. Bound to a wheelchair and oxygen tank in the end, her father died of a heart ailment in January 1963, but not before having praised Joan as “gay, amusing, intelligent, and … fully aware of all that is going on worldwide,” and thanked her profusely, particularly for all she had done for her aging parents: “you should feel your scapulae each night to detect the first sprouting of wings.” He singled out Joan’s efforts in 1960, when Marion had been diagnosed with mastoid and brain cancer, and Joan had flown to her side.

From Paris, Joan now mentally followed Marion’s medical appointments and treatments, calculating the right times to phone for news. During trips to Chicago, she took the parental role, accompanying her mother to Billings Hospital for her cobalt radiation treatments, comforting her when she wept after they sold her old Chevrolet, and delighting in Marion’s girlish pleasure when Joan did Christmas, down to stockings and a tree, as Marion always had when she and Sally were small. (Except for that one long-ago winter with Barney in Paris, Joan had never missed a Christmas in Chicago.) Marion’s fragility, isolation, and courage broke Joan’s heart, and, because of her open distress, Joan seemed to her Chicago friends more human than before.

The home of her School of the Art Institute classmate, painter Ellen Lanyon, and her husband and fellow painter Roland Ginzel, served as a place to unwind. Joan would show up toting her own bottle of bourbon or Scotch and hang around until her hosts “sort of shoveled her out of the couch” and drove her home. At their New Year’s Eve party one year, she drank vast amounts of highly potent punch, as did Dennis Adrian, critic for the Chicago Daily News and acid wit of the art community. Artist and critic got into a huge argument, and, to everyone’s horrified fascination, Joan “took [Adrian] out … absolutely took him out.” At another party, at the Lake Shore Drive apartment of Mitchell collectors Congressman Sidney Yates and his wife Addie, Joan ran into printmaker June Wayne (Addie’s cousin), and the two discussed the (never realized) possibility of Joan working at Wayne’s Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles. Still another time, perhaps in 1963, Joan accompanied dealer Bud Holland, whose Holland-Goldowsky Gallery had shown her in 1961, to the home of collectors Muriel and Albert Newman, she trained as an artist and he (according to what Joan wrote Mike) a businessman who “(supposedly … made his millions on rubbers and Negro hair straighteners). Well—Picasso—Leger etc. You couldn’t see the forest for the trees and all he talked about was money money money—oh nausee—ick.”

With “genius Frank” O’Hara at Frémicourt, c. 1960 (Illustration credit 11.6)

That same Christmas, Joan flew from Chicago to Santa Barbara, where she stayed at the beachfront home of Newt and Sally, a voracious reader, accomplished sportswoman, civic activist with a flair for filing and winning lawsuits, and overbearing mother to sixteen-year-old Sally (called Poondie), fourteen-year-old Newt, and twelve-year-old Mitch. Joan took marvelous walks with Sally’s dachshunds on Butterfly Beach, and the two sisters, who loved and hated each other, stayed up all hours, smoking, drinking, “shooting the shit,” and chewing over the matter of parenting.

Riopelle’s daughters, Yseult and Sylvie, had continued to travel to France for each summer vacation, at the approach of which Joan invariably wrestled with mixed feelings. A devoted stepmother, she gave a lot but also demanded a lot. She had grown particularly close to shy fourteen-year-old Sylvie, who played Joan to Yseult’s Sally: Sylvie wrote poetry, earned good grades, demonstrated a certain intellectual curiosity, and played a decent game of bridge. Now Yseult, a pretty and very social fifteen-year-old who did her father proud on the Serica and ski slopes and asserted her independence by getting into trouble at school, had moved to Paris full-time. At first the teenager had slept in their living room (only steps and a swinging door away from Joan’s studio), but eventually they rented for her an apartment downstairs in their building.

Joan accompanies her cancer-stricken mother to Billings Hospital in Chicago, c. 1965. (Illustration credit 11.7)

Not only Yseult and her friends, but whole armies trooped in and out of Frémicourt, which meant that Joan had precious little privacy in her studio, and, given the vicissitudes of life with Rip, little studio time, period. She had decided not to try to work in the summer, when the household decamped to Golfe-Juan. Back in Paris in September, she would pick up her brushes at last and knock out “very violent and angry paintings.”

That summer, and the two that followed, they were joined in Golfe-Juan by fifteen-year-old Rufus Zogbaum, the son of Zog and his ex-wife Betsy, who had been the companion of Franz Kline during the painter’s last years. Still grappling with Franz’s death, along with the usual problems of adolescence, Rufus found Joan and Jean-Paul, especially Joan, kind and giving in unconventional ways. And he marveled at their talent for beguiling the moment: Jean-Paul tooled around the Côte d’Azur in a magical gold Bugatti with a wooden steering wheel, and the two more or less lived at Chez Margot, a port bistro in Golfe-Juan whose patronne kept their mail and rented them a furnished room near the harbor. They trailed a retinue of children, dogs, domestics, and sailors and their families, plus a bevy of friends—Anglo-Irish painter Anne Madden and her husband painter Louis le Brocquy, May and Zao Wou-ki, composer Earle Brown, mechanic Elie Philippot and his wife Françoise, Pierre and Patricia Matisse—and visitors including Irving and Lucy Sandler, Marion’s doctor from Chicago, and the Rolls-driving heir to the Pepperidge Farm fortune. They all schmoozed over drinks sur la terrasse at Chez Margot or around the long table aboard the Serica, amid a clutter of cameras, playing cards, and packs of Marlboros and Gauloises.

Joan and Jean-Paul in their living room at Frémicourt, c. 1963 (Illustration credit 11.8)

Once they drove up to Vence, where Pierre Matisse gave them a private tour of the exquisite chapel decorated by Henri Matisse with its intensely yellow, green, and blue stained glass windows. Joan was profoundly moved. Another time they rendezvoused at sea with the yacht of millionaire financier and Riopelle collector Joseph Hirshhorn and his bride, Olga. Sometimes they stayed at the Hirshhorns’ villa in Cap d’Antibes, where, during long, idyllic days of swimming, eating, and chatting, Joan tutored Olga in French and was “so nice” to her in a dozen other ways. Both Olga and Joe not only grew immensely fond of Joan but also fell in love with her paintings, of which Joe purchased more than a dozen for the collection that would anchor the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. Hirshhorn gave Riopelle the artistic respect he was due, but Mitchell!—“one of the great artists, one of the greatest artists in the world.”

The gang at Chez Margot: Joan, Patricia Matisse, Chan May Kan, Jean-Paul, and Zao Wou-ki, c. 1963 (Illustration credit 11.9)