Not only Sally but a raft of friends and admirers showed up for Joan’s opening at the Whitney, many of them marveling at her abiding faith in painting and astounding capacity, even in relative isolation, for art making of the highest caliber. She exhibited ten single canvases, two diptychs, one quadriptych, and nine immense triptychs (the largest measuring almost nine by twenty-four feet). Among the latter were Les Bluets (The Cornflowers), a triple sampler of luscious blues and whites, and the restive Clearing, a slow dance of slabs of radiant jet black with Os of phosphorescent lilac-cloud.

In her catalog essay, Marcia Tucker quoted the artist: the work “comes from and is about landscape, not about me.” Critic Carter Ratcliff would later respond, “This supports the notion that her painting refers to the external world. It contradicts the notion that she is an Expressionist. Understandably, Tucker tries to qualify this seemingly peculiar remark: ‘Mitchell continues the romantic tradition of landscape paintings as ‘a focus for our own emotions,’ but in her case ‘emotions are metaphoric rather than personal.’ ” The boundary between Joan’s psyche and the world still easily liquefied: about me, not about me, the two can be nearly the same.

The public warmly received her show at the Whitney. They loved its landscape qualities, its colors, its force. The work reminded Marion’s old friend, poet and editor John Frederick Nims, of “a Biblical epic I just saw on television … The Red Sea opens for the Israelites to pass through, and as they do they look up at these great churning walls of water towering above them on both sides … All that raw power, but so controlled.” But the art world again gave Joan rather short shrift.

In the early 1970s the art market and anti-market were driving an unruly pluralism that included process art, body art, photorealism, earthworks, performance art, and more. Conceptualism gave rise to theory- and language-based, sometimes objectless, art, while the women’s movement, war in Vietnam, and Watergate scandal stirred a new social consciousness. Painting, especially painting as romantic calling, felt egocentrically disengaged from both theory and society. “Dropped gradually from avant-garde writing without so much as a sigh of regret,” as one critic put it, painting was supposedly dead. Mitchell was passé. Reviews were few and, by and large, tepid.

The art world’s indifference rankled. Hungrier than she would admit for what she scorned as “career crap,” Joan threw out her chest, proclaimed herself AEOH (Abstract Expressionist Old Hat), and took up cudgels for painting—“real” painting, that is. Art dealer Klaus Kertess, whose first encounter with her two years earlier had been marked by the artist’s accusation that he had helped kill painting, now earned a vigorous slap in the face for his less than rhapsodic response to her show.

Meanwhile, feminists like Tucker were disposed to champion Joan’s art. Her show took place in the context of the Feminist Art Movement, specifically, several years of pressure on the Whitney from Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), a group fired up by the museum’s inclusion of only eight females among the 143 artists in its 1969 annual. In 1972, Women in the Arts (comprised of some four hundred artists, filmmakers, writers, actresses, and dancers) had pulled off a spectacular protest at MoMA, and, the following year, that same organization had stirred up the scene with the juried show Women Choose Women (including Joan’s Sunflower V) at the New York Cultural Center. Now, in a review for New York magazine, art historian and reluctant feminist Barbara Rose anticipated the day when brilliant female artists would no longer have to play second fiddle to mediocre males and praised Joan’s show as “truly outstanding.” Rose led her piece by recalling Life’s 1957 article “Women Artists in Ascendance,” especially the shots of Joan, Helen Frankenthaler, and Grace Hartigan “with their huge paintings, standing there confidently in paint-splattered jeans when their contemporaries were all wearing tweedy classics in the suburbs, terrorized by the ‘feminine mystique.’ ”

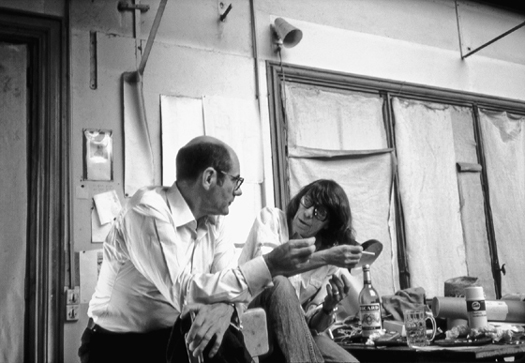

Joan with Clearing at her breakthrough 1974 exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum (Illustration credit 13.1)

Feminists no doubt expected Joan to rally to their cause: instead they found her cranky and contentious. Although she did beef about discrimination against female artists, she refused to differentiate herself from male artists, who, she insisted, had always helped her more than female artists, and, agreeing with Grace that feminist activists were inferior artists who organized to cover up their own inferiority, she refused to carry the banner of women’s liberation. Joan loved art and artists, as opposed to art by women and women artists, and most definitely did not want to be considered among the forgotten or neglected, resurrected by feminists. But de facto she was.

At the same time, Joan’s lived experience with Riopelle made male privilege a very sore point. Along with Grace, Helen, Louise Nevelson, Worden Day, and others, she attended a meeting at the uptown carriage house studio of artist Ilse Getz to discuss the possibility of organizing a women-only exhibition in order to open the eyes of museums and galleries. She also showed up at a consciousness-raising meeting at Elaine de Kooning’s studio, where she made nasty cracks about feminism and growled that she was already liberated.

Ironically, in a just-published feature article by Cindy Nemser in the Feminist Art Journal, based on the writer’s 1972 visit to Vétheuil, Joan had griped about carrying

the burden of running [Riopelle’s] household, taking care of his children and grandchildren and though she’s not legally his wife, cooking and cleaning. “Well,” she admitted truculently, “I let things pile up, but if the housekeeper doesn’t come and it gets too bad, I do it. How can I let Riopelle do it, he’s not well [well enough, however, to go on a hunting expedition that year that took him above the Arctic Circle] … but of course, I have a bad back myself.”

(Joan cited her bad back as the reason she repeatedly interrupted the interview to take her coffee mug into the bathroom and fill it with Scotch. She drank for medicinal purposes, she told Nemser.) When the writer asked whether women artists faced discrimination, Joan put her own twist on the concept, responding that they did, especially as they aged, and bemoaning the fact that older women were no longer considered sex objects. “ ‘Yet,’ she asserted adamantly, ‘they still have sexual desires and still want to fuck just like the men—but nobody wants to fuck with them.’ ”

Her five weeks in New York gave Joan ample time to catch up with friends, including Mike Goldberg, Tom Hess, Bill de Kooning, and Harold Rosenberg, who did write a vigorous appreciation of her Whitney show for the New Yorker in which he positioned her as a renewer of the great tradition of Abstract Expressionism. A figure from a more distant past, John Frederick Nims met Joan for a drink that stretched into many drinks. “But it really was great,” the poet later enthused. “Not just the Scotches, but seeing you and talking about the Dear Dead Days and the not so dead ones. You’re good to talk to; You Throw Light. As well as warmth.”

Less agreeably, Joan had picked a nasty fight with David Anderson on the eve of her opening, after which Anderson received notice from her lawyer that the Martha Jackson Gallery’s representation of Mitchell was terminated for cause. Having perceived a tailing off of the gallery’s effectiveness in promoting her art and watched dealer Xavier Fourcade work wonders on de Kooning’s sagging career, Joan, disdainful though she was of artists who razored their way ahead, had made her decision even before flying to New York. Anderson was issued instructions to transport Joan’s paintings to the Fourcade, Droll Gallery on East Seventy-fifth Street.

The son of a wealthy French banker, Xavier Fourcade had begun his art career in 1966 when he took the position of first director of contemporary art at New York’s prestigious old-line Knoedler Gallery. A patrician and rather shy man whose shyness was often interpreted as hauteur, Xavier had probably met Joan through his brother, French poet and Matisse specialist Dominique Fourcade. In any case, Xavier had asked Joan for advice about which artists to recruit for Knoedler, and she had suggested de Kooning. The dealer liked the idea, which was seconded by former ArtNews editor Tom Hess, who remained close to the Abstract Expressionist. Fourcade then proceeded to secure for de Kooning major exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, the Stedelijk, and the Tate. When Fourcade left Knoedler to start his own gallery, de Kooning had followed. Fourcade, Droll (the partnership with dealer Donald Droll would be short-lived) opened its doors in 1970. Besides de Kooning, the new gallery represented Tony Smith, Michael Heizer, Louise Bourgeois, and the Estates of Eva Hesse and Arshile Gorky.

On the day of her Whitney opening, Joan had phoned Xavier, who was in bed with the flu: “You want to be my dealer? Come to my opening.” Aware that illness was no excuse in Joan’s book, Xavier unsteadily got up, donned a suit and tie, attended the reception, and walked out as her New York representative.

A few days later Joan wandered into the Martha Jackson Gallery and chatted amiably with David, then arranged, as part of their negotiated settlement, to give her major painting Ode to Joy to his wife, Becky Anderson, a way of simultaneously thanking the couple and nettling David.

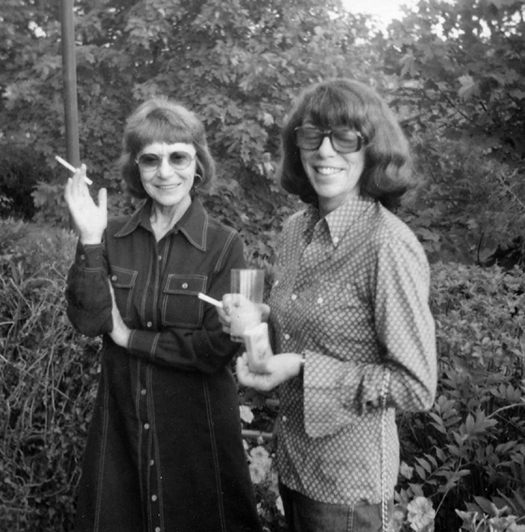

Joan chats with her New York dealer Xavier Fourcade in her studio, 1980s. (Illustration credit 13.2)

. . .

Meanwhile, back at the Monet ranch, as Joan’s old pal Joe LeSueur liked to say, Iva (pronounced “Eva”) awaited. A gift from Guiguite Maeght, Joan’s German shepherd puppy had arrived unexpectedly in the arms of Jean-Paul shortly before Bertie’s death. Burned out by caring for her elderly Skye terrier, Joan had at first objected to having another dog, yet she swiftly lost her heart to the nervous, scrawny creature she nicknamed “Lily Marlene.” Iva had style.

From then on, life at La Tour revolved around Iva, with Joan mothering to an extent some found pathetic and obsessing on every detail of her dog’s schedule and care. She trusted Iva’s love—deep, wordless, and nonjudgmental, unlike that of humans—and considered the puppy a surrogate for or continuation of herself: “She’s a total extension of me, or I am of her.” Joan still believed that she herself had “no identity but painting, psychologically,” while her training of Iva gave the dog “an identity and a feeling of self-worth,” a fix on the selfhood Joan found, except through painting, so elusive.

Notwithstanding Iva’s companionship, Joan still experienced intense dramas of merging and separating. At times frighteningly alone, she would lapse into states of agitation. Riopelle came and went. Sylvie (who had recently lost twins at birth) was living at La Tour. Old friends like Shirley Jaffe, Zuka, Jacques Dupin, Pierre Schneider, Nancy Borregaard, and Jean Fournier would drive out for lunch or dinner, sometimes an overnight, and John Bennett still visited every few weeks. Houseguests from the States included art dealer Grace Borgenicht and her husband, painter Warren Brandt, Pierre Matisse, Joe LeSueur, Hal Fondren, Martha Bertolette, Tom Hess’s son Philip and his wife Margaret, and Joan’s niece Poondie, now in her early twenties. Between times, La Tour could fall eerily silent. “I’m very interested in people,” Joan contended. “But for some reason, I remain isolated, no matter how I try.”

She worked to her advantage the fact that most guests were at the mercy of taxis and trains. A case in point was the visit of Samuel Beckett’s biographer Deirdre Bair, who had been invited to lunch. (Over the years, Joan and Sam had drifted apart, Joan telling one friend she had had to break with the writer because he was so depressed.) Bair had appointments back in Paris that afternoon and evening, yet Joan, drinking heavily, refused to let her leave, and Bair missed train after train. Aware of his biographer’s movements, Beckett phoned several times: Joan, you have to let her go! But Joan did not.

Joan often “tested” her guests, and the more she’d been drinking, the more outrageous the test. When her old friend, painter Jon Schueler and his wife, art historian Magda Salvesen, lunched with her at La Pierre à Poisson, the local restaurant she had made an extension of her dining room, Joan deliberately misconstrued virtually every remark the two made. Another time, Joan greeted a friend of her sister’s by announcing that Sally had had an affair with the woman’s husband, then proceeded to needle her guest about the husband’s infidelity until at last the Californian fled in tears. In contrast, she lavished kindness upon painter Kimber Smith, who, at her insistence, stayed at Vétheuil while he received radiation treatment in Paris for the cancer he faced with a courage she admired. Kimber had long since passed his test.

Young people too, mostly fledgling painters or writers, visited La Tour, some sent by parents or friends who knew Joan, others having crossed her path in New York or Paris, still others having screwed up the nerve to phone. Those she liked she pulled in fast. Most were intrigued by her realm of music, books, liquor, painting, dogs, landscape, and home-style French cooking, and even more so by their fractious, dry-humored, anxiety-ridden, salty-tongued, self-concept-rattling hostess. One way or another, all got more than they expected, and many felt their relationships with Joan were special.

Typically, she grilled her young guests, which was “horrible,” reports Lise Weil, today a writer, “but it came from a place of deep caring. It didn’t feel like get-the-guest.” (On this point, not everyone agreed.) Endlessly curious about their childhoods, family problems, love lives, and life plans, Joan would rattle on about overcoming one’s upbringing, attending to one’s feelings, living more on the edge. She made Lise, for one, study pictures of prisoners in Attica in order to feel more intensely. The artist brimmed with disdain for racists, slow wits, bad painters, “silver-spoon people,” Californians, academics, and snobs. Nondrinkers got mercilessly ragged, young women from the Seven Sisters were dubbed “Vassar” or “Radcliffe,” anyone who used the word “should” was ripped into. As for fledgling painters, they were forbidden to waste time wallowing in self-doubt. Joan geared them up with brisk admonitions: “Be a serious painter!” “Get crackin’, man!” “C’mon, let’s blow a pic!” Most came away from a stay at La Tour with important new insights about themselves.

Among the young writers who had earlier caught Joan’s attention were the then-unknown Lydia Davis and Paul Auster, who had come to Paris in 1971 and were scraping together a living from translations. One evening the couple had been invited to dinner, along with Joan and Jean-Paul, at the home of Christine and Jacques Dupin, whose poetry Paul had translated as a student at Columbia and with whom he had formed a warm friendship. Joan arrived wearing smoky-lensed glasses and looking rail-thin in black. She was already well lit up. Mesmerized by Paul’s large, sensual, dark-rimmed eyes, she began taunting him. “She talked sans cesse of Paul’s eyes,” Davis recorded in her journal, “ ‘does he take drugs, does he wear contact lenses?’ How he must be a phony with eyes like that, how he must be an egotist to have not gone to her ‘vernissage’ in Paris. (Of course he didn’t know of it.)” Riopelle dozed on the sofa, and the Dupins, who spoke little English, struggled to follow Mitchell’s relentless battering of the flabbergasted Auster: “Who do you think you are, Lord Byron?” But his sangfroid got him through the test, and, the following week, he and Lydia were invited to La Tour, in its May splendor of flowering chestnut and cherry trees, lilacs, and variegated tulips.

Lydia was struck by the household’s orderly routine, delicious meals, and devoted attention to dogs. The two spent a pleasant evening and stayed the night. The next morning, Lydia walked up to the studio to find Joan listening to the radio as she worked, friendly, “serious … and ‘centered’—quite different from the fragmented person who had baited Paul that first evening.”

From then on, Lydia and Paul were invited to Frémicourt or Vétheuil every six weeks or so. That July, with Lydia away in Ireland, Paul went out alone, and he and Joan talked for hours. “My stay was marred somewhat,” he reported to Lydia, “by one of their typically senseless and brutal arguments after dinner, during which she cried and after which he simply fell asleep with his head on the table … I am of the opinion that he treats her like a shit.” At first shocking and disturbing, their fights quickly felt boring and sad.

Generous, kind, and approving of Davis’s and Auster’s strength of purpose as writers, Joan showed genuine interest in their manuscripts, gave Paul a beautiful etching of a sunflower for the cover of the literary magazine he and a friend were starting, and arranged for him to meet Beckett. She earnestly told Lydia that she must have children and would regret it if she did not.

Another young writer friend of Joan’s, the beautiful, pale Christian Larson, lived on the Île Saint-Louis and hung on the edges of the Paris Review crowd. He stuttered and suffered from severe writer’s block. Having prized out the details of his cosseted but troubled New Jersey childhood—an adoring mother, a rejecting father, complex feelings about his sexuality—Joan gave Chris money after his father cut him off and eventually got him writing, leaving him deeply grateful “to Joan, who knows how to bring people out of themselves, who knows how to make people make an effort.”

She also introduced him to J. J. Mitchell (no relation), a fabulously handsome creature, once Frank O’ Hara’s lover and soon Chris’s, who lived for several months at La Tour, ostensibly to dog-sit and edit Marion Strobel’s poetry for a memorial volume that never saw the light of day. A gregarious charmer with killer blue eyes and perfect white teeth, this alumnus of Harvard courted self-destruction with booze, drugs, and trashy nightlife during his weekly jaunts into Paris. Joan would tuck a big bill or two into his pocket and tell him to have a good time. Back at La Tour, J.J. wrote a friend one four a.m.,

Here we are—les brouillards [the fogs] coming up Monet-like over the torn-up tulips. I’m wavering between petulance and patience, skeptically surveying the only comfortable couch dans la maison Mitchell … I (JJ) hereafter known as boy amanuensis/typist whose fluency and lack of facility matches the finger-painting (yes) and spoken scribblings of girl painter J., currently sprawled in flop/art style in visible attack on unsuspecting canvas(es) … enjoying a brief respite (moi aussi) from J.P. who fishes in Canada after leaving us hair-raising nightmarish stories of tail-gunning runs on Dresden.

Since 1970 Jean-Paul had been spending two months a year in Canada, fishing in the spring and hunting in the fall. From Montreal, he would dash off to Joan brief, impersonal postcards that closed with the formula, “With great friendship.” In the fall of 1974, he had departed earlier and stayed longer than usual. Leaving J.J. to dog-sit, Joan joined him that November in the mountain village of Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson, north of Montreal, where, using an inheritance from his mother, who had died two years earlier, he had just built a lovely architect-designed studio-home next to a picture-postcard lake. With his pal, Montreal radiologist, private pilot, and outdoorsman Champlain Charest, he had also purchased the local general store, which the two were transforming into a gourmet restaurant.

In honor of Joan’s arrival, Champlain and his wife Réjeanne took pains to prepare a typical Quebecois feast with roast game. In an execrable mood, Joan never touched her dinner, instead drinking, chain-smoking, and finally disgustedly lowering her plate for the dog (recalling the time she served dog food to a group of Canadians whom Riopelle had forced her to entertain). She slept all day every day, and, when she did join the others, spoiled everything by picking petty fights with Jean-Paul. At every turn, she saw him slipping away from her. His new home—number six, counting Vétheuil, Frémicourt, St.-Cyr, the foundry in Meudon, and the Serica—belonged to a life she did not share. To Joan, it felt safer to hate than to love: if you love, you have no defense.

Her other defense was the landscape, which she used “for enormous protection from people who were hurting me.” In the wake of her trip came the gorgeous Canada paintings. The diptych Canada V beguiles with its bosky masses, its incantatory lights and darks, its use of white around the cut between its two panels, and its oddly right colors (pale mint, white, claret, and the color of night). The brumal Returned pulls taut a tourniquet of white light across the four panels where silent, soft-edged, judiciously placed shapes appear. (Originally, Joan titled the latter Canada and gave it to Jean-Paul, but she changed its name after he discarded it. Another painting bears the title Also Returned.)

Back in France, life continued unsettled. Learning that their Frémicourt building was to be demolished on March 15, Joan enlisted J.J. to help her sort through the vast piles of rolled canvases and cartons of magazines, catalogs, and books she and Jean-Paul had been storing there, and the past came roaring back. Overwhelmed, she squirreled away dozens of paintings in the cistern at Vétheuil and dumped everything else in the living room.

They finished the move only a day or two before Joan’s fiftieth birthday, which she spent home alone with Iva. On that milestone occasion, she had planned to stop drinking, yet she managed only three days without alcohol. Nor had much come of her attempts to cut down on her two-pack-a-day Gauloises habit. Frequently tired, she suffered from chronic hip and back pain—lumbago, she claimed, the upshot of too much skating—yet she remained tough and funny in an ironic, self-deprecating way. In truth, she was battling depression: the ghastly metallic white lurked on all sides.

All that summer and fall, painting eluded her. Having sometimes managed to kick herself by switching mediums when she got stuck, she had J.J. type up some of his own poems, which she cut out, pasted as shapes on sheets of art paper, and “pasteled up.” (Other times she used charcoal or Conté crayon.) She planted his blithe stacked poem “Sally Up My Alley” (“You’re / my / tanned / and / tantine / Sally / my / Santa / Barbara / family …”), for instance, inside a post-and-lintel shape, both diaphanous and vigorous. Chris came out to Vétheuil most weekends, and they did his poems too, and then, having fun, went on to tackle work by Pierre Schneider, Jacques Dupin, and James Schuyler. Black on white to non-synesthetes, the poets’ words, of course, appeared to Joan as multicolored as confetti: the poem-drawings, a secret in plain sight.

They were also a testimony to her capacity for generous friendship. Refusing to sort people out by worldly importance, Joan brought the same intensity to her collaboration with the unknown J. J. Mitchell and Chris Larson as she did to her (indirect) collaboration with her old friend, well-known poet and future Pulitzer Prize winner James Schuyler. Pierre Schneider exhibited these little jewels at an alternative gallery in the Marais, after which Joan gave most of them to the poets or other friends.

Her effort notwithstanding, year’s end found Joan deeply depressed. As alarmed that fall by Chris Larson’s deteriorating mental state as by her own, she had been prodding him to see a therapist and phoning his family and friends to try to enlist their support. On January 24, 1976, however, he killed himself by slitting his wrists in the bathtub of his Île Saint-Louis apartment. Joan reacted with outsized grief and anger, no doubt all the more intense given her need for self-defense against her own suicidal bent.

Whenever a friend died, Joan painted a tree as both homage and act. Thus Chris’s Dead Tree made another place for Chris Larson in Joan’s imaginary photo album and kept him forever alive and protected. Does it have a real-world counterpart that meant something to Chris? Are its colors—charred green black, lilac, flecks of aqua and white—those of his voice or of his personality? In any case, in the lush, stunted, and splendid Chris’s Dead Tree, the abyss yawns and spring blooms in Vétheuil.

At the very time Chris lay dying, Iva gave birth to eight puppies, two of which Joan kept. One she named Marion after her mother, and the other Madeleine, after Madeleine Arbour, so that Jean-Paul was forced to use the name of his supposed mistress each time he called the dog. Joan doted upon the “Three Graces,” but guests were typically less enchanted. “When they bit,” reported one French journalist of the trio of barking, bounding, thumping police dogs, “they were said to prefer the ankles of art dealers, journalists, and other unwelcome visitors whose fear and misfortunes the mistress of the premises, a present-day Hecate, contemplated with delectation.” When one of her darlings lunged at Xavier Fourcade, however, Joan scolded, “No! No! Not him! He pays our bills!”

By the time the puppies arrived, Riopelle was more often absent than not. Speaking seriously one day, rather than hiding behind his usual humor, the Canadian had lamented to Roseline that Joan “destroyed everything that came near her.” Another time, a visiting American friend whom he was driving out to Vétheuil casually inquired why he didn’t marry Joan: Jean-Paul stomped on the brake, flung open the passenger door, and ordered the man out of his car. For Riopelle, relationships were all or nothing, and his world had long since stopped revolving around Joan. Yet, never one to address problems directly, he let things drift, claiming that she would commit suicide if he left her. Theirs was now a sailor’s “marriage” and a long day’s journey into night. His presence at La Tour inevitably brought dreary, alcohol-coarsened battles, with Joan’s withering put-downs, sly righteousness, and iron-hard verbal assaults as tiresome as Jean-Paul’s storming around and roughing her up.

One winterish afternoon, for instance, as Joan and John Bennett chatted and sipped white wine in the living room, a slam of the door announced Jean-Paul’s arrival. Joan snatched a book as if she had been reading.

“I thought I told you to leave the door shut! This is just running the heat!” he greeted her.

“Oh, ah, well, I don’t know, I don’t know. I’m reading my book.”

He stomped across the room, grabbed the book, and ripped it in half.

“Here! Maybe this will help you read your book!”

A big macho bear with an easy grin, cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth, slightly dissolute look, and wild mop of plaster-dust graying hair, Riopelle continued to captivate virtually everyone, from the local butcher to the most distingué art critic, and still found a ready supply of sex partners. Despite a few casual affairs, Joan did not.

Her well-lined face now showed all the signs of hard living, and she wore big, smoky-lensed magnifying glasses behind which those enormous eyes, thought one visitor, “looked like huge eggs swimming in dark liquid.” Moreover, her lack of appetite—she craved only cigarettes and booze—had left her spiky and thin, and, while she continued to move like an athlete, she did so less nimbly because of her back and hip pain. She might don an elegant pantsuit to trot off to Paris, but most days she threw on a jogging outfit or a pair of jeans and ratty old sweater.

Having lost her seductive charm, but not her irresistible vitality, Joan saw limited options, and, if she made sporadic efforts to rekindle the old feeling with Rip, it was out of yearning for the comfort and familiarity of a loving relationship. Sometimes she would draw a hot bath for him, but he would stride into the bathroom and pee into the tub. No matter how difficult and repulsive she found Jean-Paul, however, she needed him too: if nothing else, to inflict pain upon him was to forget her own suffering. Worst of all were those times when, the two old warriors too weary to battle it out, an ominous silence hung in the air.

As for Riopelle’s art, Joan remained publicly loyal, but, in truth, she could muster little enthusiasm for his return to figuration. The artist’s acquisition of a taxidermied owl from a local antique shop in 1969 and encounter with Inuit string games during a 1971 hunting trip to northern Canada had supplied him with new subjects bound up in both empirical reality and Canadian symbolism. Many critics agreed that the paintings and sculptures of the 1970s were a cut below the classic Riopelles of the 1950s and 1960s. Moreover, though money still burned a hole in his pocket, his sales had dropped. He was beginning to look like the hare, and she the tortoise. The rival in her gloated, but the companion rued that he wasn’t keeping up his end of the bargain. He snapped back: her canvases were painted by the whiskey, not the artist.

Indeed, Joan’s efforts in the studio were still not resolving themselves into a new painting direction. True, she was by now a crafty old magician able to shuffle and reshuffle pictorial strategies and pull out what she needed. That may have happened rather easily in the case of the vigorous Red Tree, indebted simultaneously to Mondrian, van Gogh, Mitchell of the fifties, and her winter-naked linden. But for months she had struggled with the allover diptych Aires pour Marion, a glen of electrified duskiness bisected by the whiteness around its vertical cut, a strategy she had tried out in Canada V.

However, a metamorphosis was shaping up with Quatuor II for Betsy Jolas. While waiting for Jean-Paul one day in his studio, Joan had gazed out a window upon a copse with marvelous flirting lights between certain trees. She made a sketch on the spot and soon began painting. The delectable Quatuor II for Betsy Jolas lusters with lilac, grass green, fuchsia, green black, and white. Each of its four panels manifests its own visual logic and completeness, yet everything relates to everything else—from the velvety-dark knots on the left to the whoosh of pure white, as explosive as laughter, on the right, to the germinal elements, the tree-inspired “up and down things,” in the center. (As for the work’s title, it reprises that of the recent Quatuor II for string trio and soprano by her friend Betsy Jolas. And could the lilac of Joan’s Quatuor II be anything but soprano?)

In Straw, which came on the heels of Quatuor II, it is as if the viewer has backed away from the central panels in Quatuor II, out of the illuminated stand of trees and into a field so sunny it blazes up. Long, horrent strokes of ochre, Straw’s “up and down things” bristle across its lower edge as strokes of dark thalo green chop up its top right. Like van Gogh, whose wheat-fields palette Straw borrows, Mitchell uses graphic markings to evoke vibrations of wind and light. But her facture is rougher than his, and she pulls apart the fabric of her painting to reveal its white ground, thus insisting upon spatial discontinuities. Like Cézanne, she remained fascinated with the way visual relationships shift with every move of one’s head and she played with the slippage between two dimensions and three.

That October, Joan’s shipper picked up and crated forty-seven paintings—including Red Tree IV, Aires pour Marion, Quatuor II pour Betsy Jolas, and Straw—which Joan and Jean Fournier accompanied to customs at Roissy airport. Having never procured the carte de séjour required for foreigners living in France nor paid French income tax, Joan had put herself in a tricky position when it came to shipping paintings abroad for commercial use. Her strategy was to declare them unfinished sketches, her personal property, and her ploy, that year in any case, to feign mental incompetence so that Fournier, with his marvelous savoir-faire, could handle the paperwork required to ship them to 60 St. Mark’s Place, where they were picked up by the Xavier Fourcade Gallery and transported to 36 East Seventy-fifth Street.

Intimate and European in flavor, Fourcade’s townhouse gallery, its two floors linked by an elegantly banistered staircase, consisted of several small rooms with hardwood floors, a beautiful mix of natural and artificial light, and only one long uninterrupted wall. Selecting and hanging a Mitchell show for that space was always a challenge. Joan and Xavier would work together on installations, Xavier giving Joan the last word. After she flew to New York that November, they mapped out the placement of twenty-five paintings: Quatuor II fit the big wall with only eleven inches to spare.

Even though the new paintings were less readily seductive than those of the early 1970s and the height of the tallest among them surpassed that of the ceilings in most postwar apartments and suburban homes, many (including Quatuor II, priced at $35,000) immediately sold. Not only did Fourcade bring a fresh client base, but also he was professional, driven, and highly effective. After fifteen years of scant recognition in New York, Joan saw an abrupt shift in the arc of her career: she had more market success than she had had in a very long time. Eventually Paris would follow. (Fournier and Fourcade had begun alternating Mitchell exhibitions and cycles of paintings, thus setting a tempo for her production.)

Joan’s two dealers resembled each other in ways that went beyond their names. Both were French, homosexual, cultured, and publicly reserved yet privately warm (Xavier, unlike Jean, prone to fits of nervous yelling during installations); both deeply believed in her work; and both established close friendships with Joan.

With Elaine de Kooning, 1975 (Illustration credit 13.3)

For her New York openings, Xavier would throw wonderful dinner parties, not for wooing collectors but for gathering friends, either at the gallery or at Mortimer’s, a ladies-who-lunch bistro at the corner of Lexington and Seventy-fifth. (Refusing to compartmentalize people, Joan put together guest lists that included art world luminaries like art historian Linda Nochlin and artist Malcolm Morley, but also Patricia Malloy, her tenant at St. Mark’s Place, and Poondie Perry, her niece.) Xavier also procured for Joan special morning passes to the Museum of Modern Art, escorted her to concerts at Lincoln Center and operas at the Met, and invited her to lively weekend house parties at his second home in Bellport, Long Island, along with Morley, Tony and Jane Smith (he, the sculptor, and she, the actress and opera singer), and others. And each time Joan set eyes upon the Mitchell that graced Xavier’s library at Bellport, she insisted she could improve it. That upper left section was wrong—“too Helen Frankenthaler!” But Xavier never let her lay a finger on it.

The first of Joan’s seven shows at Xavier Fourcade opened on November 23, the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, a holiday the artist spent in Manhattan with her sister Sally, Sally’s children, and the young painter Hollis Jeffcoat.

A year and a half earlier, Joan had received a phone call from a twenty-nine-year-old admirer named Phyllis Hailey, who had wanted Joan to critique her painting. A free spirit from Nashville, Tennessee, with college, a failed marriage, and one year at the New York Studio School behind her, Phyllis was studying at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and eking out a living by selling portrait sketches to tourists in Montmartre.

Joan had quickly taken Phyllis under her wing, teaching her to be more visual and more feeling in her work, insisting she unfailingly know what she was doing when her brush hit the canvas, and endlessly talking color. She gave Phyllis tubes of the very best Lefebvre-Foinet oils, but no canvas because, she claimed, Phyllis wasn’t yet good enough to paint on canvas. So the younger artist used watercolor blocks for her studies of Joan’s garden, the church, the river, and a certain ginkgo tree whose foliage she broke up in a quasi-Impressionist manner. Her work became stronger and freer. In addition to doling out painting advice, Joan loved to “shrink” this rather naive young woman, bolstering her self-confidence and prodding her to live more fully her identity as an artist, even though, Joan stressed, so few people took women artists seriously. Phyllis wrote home that Joan was “truly doing wonders for me painting-wise and person-wise.” That went both ways. One of the many notes Joan scribbled for Phyllis reads, “Well if it means anything to you—you got me painting again … just being in the studio with you makes me want to work … I love you dearly—and it takes a shafted one to recognize another.”

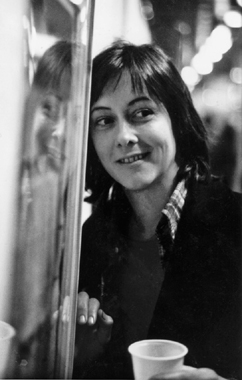

One bright June day around noon, after Joan and Phyllis had been acquainted for a year or so, they were sitting on the little terrace overlooking the Seine when Joan’s old friend Elaine de Kooning arrived. De Kooning was teaching that summer at the New York Studio School’s program at the American Center for Students and Artists on the boulevard Raspail, and she had brought with her the program’s administrator, twenty-four-year-old painter Hollis Jeffcoat, a native Floridian and Studio School graduate herself. Tall and willowy at 110 pounds, with blue gray eyes and curly black hair, Hollis was soft-spoken, poised, fetchingly androgynous, and single-minded about painting.

As always, Elaine talked a mile a minute, eventually getting around to the topic of Joan’s drinking. With help from a therapist and Alcoholics Anonymous, this once drinker to rival Joan had quit two years before. Wasn’t it time Joan did the same? “Oh, come on, Elaine! I stopped for three days, and I didn’t see any difference at all. Forget it! I don’t know why you want me to stop drinking anyway.” It was all very familiar and friendly. After awhile, the four ambled up to Joan’s studio to see her newest paintings. Elaine and Phyllis oohed and aahed. Hollis stayed silent.

“Hollis, what do you think of my paintings?”

“Not much.”

The others gulped.

“What do you mean?”

Hollis had loved Joan’s Whitney show, yet in the recent work she saw an inert materiality and relentless sameness. She felt it didn’t go far enough.

Joan had no problem with the arrogance of youth: “Well, tell me more. What would you do to change the paintings?”

Later that evening, after the foursome dined at La Pierre à Poisson, Joan dismissed Elaine and Phyllis and directed Hollis to stay on. The two talked through the night, mostly about painting, with an intensity Hollis had never known. Years after her Cedar Tavern days, Joan remained ravenous for passionate talk between artists. Before turning in, she gave Hollis charcoal and paper. The next midday she ambled out to the garden, where the younger artist had been drawing all morning. Hollis’s work passed the test, and Joan then rustled up canvas and paint.

For the rest of that summer, Hollis lived part-time at Vétheuil, helping with the dogs and reheating the dinners that Joan’s cook, Raymonde, prepared before leaving in the late afternoon. She and Joan would sing, listen to opera, loll in the garden, pad around barefoot in the grass. Once or twice Hollis tap-danced in the studio. Sometimes they spent all day in their pajamas. Hollis was Mary (“Ma-ryyy!”) and Joan was Rose (“Row-zz!”). Or Hollis was Vinnie (van Gogh) and Joan, Thea (from Theo van Gogh, the painter’s helpmeet brother). Every day they painted and batted around ideas about painting. Joan was an additive painter, and Hollis a subtractive painter: what was good and bad about each? And many secrets were divulged. Joan endlessly griped about Riopelle, who was elsewhere that summer: I despise him! I don’t want to be with him! But if I leave, he will kill himself. Hollis would reply, But nobody’s missing here. I don’t feel an absence.

Thus Hollis Jeffcoat delightfully warmed up Joan’s life. Her job ended in August, however, and she had to return to New York to teach at the Studio School. There she moved back into the Brooklyn apartment she shared with a gay painter named Carl Plansky.

During Joan’s sojourn in New York at the time of her show at Fourcade that November, Hollis and Carl had a fight, his complex feelings over her closeness to the famous painter Joan Mitchell having unbalanced their friendship. Joan used this clash as an argumentative wedge, eventually convincing Hollis to fly back to France with her at semester’s end. When Jean-Paul picked the two up at the airport, Hollis was astonished. Tanned and brimming with anecdotes, he was an electric presence, a charmer, rather than the monster she had expected. From then on, Hollis and Joan lived at La Tour, while Jean-Paul shuttled among Vétheuil, Paris, and his studios.

Life settled into routine. Most days Joan would emerge from her bedroom around one thirty to pad down the hall to the little dining room or the terrace, where she would sip from a bowl of steaming café au lait, pick at breakfast (poached eggs or a potato omelette, toast with quince jelly, bacon, and tomato), peruse the mail, pore over the Herald Tribune, do the crossword puzzle, read, maybe listen to the early-afternoon “shrink programs” on the radio, and get a start on the day’s Ricard. Eventually she would stroll up to the studio, where Hollis had been working since early morning. The two chatted, eyeballed their paintings in daylight, and dog-fed before the light got low, then headed to the library for an apéritif and perhaps some TV. Between seven thirty and nine, the downstairs light would flick on, signaling Jean-Paul’s arrival. Then Hollis heated up dinner and set the table where the three often lingered for hours, Joan and Jean-Paul regaling Hollis with tales of the old days at the Cedar, the Hamptons, the Rosebud, and the Dôme. Jean-Paul was nicer to Joan than he had been in a very long time. Finally, he would rise and either go sleep in the library or on the billiard table, or leave for St.-Cyr, while the two women led the dogs back up to the studio, where each took one end of the room. Struggling with the recalcitrant Posted that spring, Joan would occasionally call out to Hollis, “What should I do here?” Hollis would walk over and study the canvas. “Well, what it really needs is …” “Well, then, bloody well do it.”

When Joan was prey to her demons, she would pick up a brush and let fly at a blank canvas—slam! slam! slam!—then creep back the following afternoon to see what damage she had inflicted and figure out what was needed to turn the semi-mess into a painting. Agitated, anxious, sometimes falling-down drunk, she cried almost every night, over the failings of Jean-Paul, even the pointlessness of painting. She, who so vehemently believed that painting was essential and real, would sink into despair: Ah, another Mitchell! Why am I doing this? Just another Mitchell. Could painting still save her? Notwithstanding her recent success, she felt buried in the country at age fifty-one, turning out more pictures she offensively-defensively labeled Old Hat. Moreover, she was stuck in a relationship that was like the old cheese no one would throw out. Life’s possibilities had dwindled. Thus she became increasingly possessive of Hollis, a daughter of sorts and surrogate younger self endowed with the confident vitality she herself could no longer necessarily conjure up.

Meanwhile, Joan’s relationship with Phyllis Hailey had sputtered along. Spending ten days with his sibling at La Tour, Phyllis’s brother John observed the same affectionate rapport Phyllis had described in letters home, but, according to Hollis, Joan had “[thrown] Phyllis over and was abominable. Phyllis was destroyed by it.” Phyllis and Hollis had formed a close friendship, going to museums and galleries and running around Paris together—an escape from the pressures of Vétheuil—and, bankrolled by Joan, once traveling to Amsterdam, where they spent a marvelous few days.

That summer Rufus Zogbaum also visited La Tour, where this son of Joan’s once lover and late friend, Wilfred Zogbaum, and virtual stepson of Franz Kline began an affair with Hollis. Always an enthusiastic matchmaker, Joan took full credit. Not only were the two practically her children, but also their liaison encapsulated her own past. When Hollis again had to return to New York that fall, she moved in with Rufus. But they didn’t last long as a couple: “There was no question about it,” Hollis later reflected. “My real passion was with Joan. And hers was with me.” One note survives from that October: “Joanie, You were so sweet on the phone last night. I miss our fun. Did you make your clear blue winter painting? … Love you so much.”

Meanwhile, having completed and shepherded through customs her second show for Fourcade, Joan spent a delightful day with Jean Lamouroux, a painter friend from Provence, who drove her into Paris to see Paris–New York at the Pompidou and the Courbet retrospective at the Grand Palais. Around the same time, in another of the sagas of intertwined love and pain that inform Joan’s life, her Parker School classmate and sporadic lover, Tim Osato, reappeared. Now retired from the military, Osato was a man of (in the words of one of his daughters) “dashed dreams and frustrated everything.” The two saw each other a few times, then quarreled by phone. From his hotel in Paris, Tim penned a hurt note. On Christmas Day, several weeks later, he would write again, this time from the Veterans Administration Hospital in Denver, Colorado: “Having nearly broken my word to you those last few days in Paris (sleeping pills, this time), I’m back to square one and there really isn’t anything to say except that the memory of the little girl in the light blue coat at the bus stop will never leave her buddy, Tim.” Nineteen months later, he shot himself.

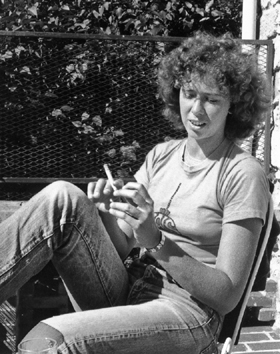

Last known photograph of Phyllis Hailey, 1977 (Illustration credit 13.4)

All that winter Jean-Paul was hobbling around La Tour in pain, a studio accident having exacerbated an old knee injury to the point where he could not bend his leg more than three inches. “J.P. has been on crutches,” Joan reported to Joe LeSueur,

and he’s afraid of an operation—well honey—to get him upstairs and down—etc. etc. Hollis [back from New York] is divine with him and he thinks she’s “the end of the world.” She has his racing helmet and Moto Solex [motorcycle] and he gives her canvas etc. Her painting is really good and has changed enormously. What do we do about J.P.’s knee? We live with this—open the back gate—hold him etc. etc. (He goes to his studio or is taken by Philippe [their handyman] and has done some 100 tiny pics seated—beautiful.)

One evening shortly thereafter, Jean-Paul, Joan, and Hollis dined with Jean-Paul’s Canadian pal Champlain Charest, after which the foursome drove to St.-Cyr to view those same tiny paintings. Attempting to flatter Riopelle, Joan “shoplifted” one of them, surreptitiously pulling it off the wall and tucking it into her bag as if to say, See! I love your painting so much I have to steal it. Later that night, after she and Hollis had returned to La Tour, Jean-Paul realized what had happened and rushed over in a rage. Bursting into the darkened house shouting and flailing his crutches, he managed to slam the nearest painting from the wall, then, as Joan burst into the room, dove into her, injury or not. Yelling bloody murder, the two tried to kill each other while Hollis did her best to break them up.

That Joan’s increasingly erratic behavior accrued in part from a longing for loving domesticity is suggested by her decision that spring to legally adopt Hollis, who was just the right age to be the child she had long desired. (This never happened, however.) Building a different kind of air castle around Hollis, Jean-Paul revealed to the young woman, one evening when Joan was out of town, that he was in love with her. Her jaw dropped. She thought he was a fun, interesting guy, but she did not love him, nor did she desire an affair. Her feelings for Jean-Paul “didn’t come close to how I felt about Joan.”

It was then decided that, to further her artistic education, Hollis would visit Italy and that Phyllis, who had been to Italy but wanted to return, would accompany her. On Friday, April 7, the two departed for Florence carrying a thousand dollars in traveler’s checks, a gift from Joan. They had planned to fly, but Phyllis had met a French couple who happened to be driving to Italy and were willing to take them along for their share of the gas money. Two hours outside Paris, the foursome stopped for coffee in Auxerre. When they returned to the car, the woman, who had only a learner’s permit, got behind the wheel. Shortly thereafter, she was pulling out of her lane to pass a semi (chatting and laughing in the backseat, Phyllis and Hollis paid little attention) when a gust of wind walloped the little Renault, and she lost control. The car rolled, lurched backward, struck a tree, burst into flames. Phyllis was ejected, and the car landed on top of her. Hollis jumped out just as it exploded into a ball of flames.

Hollis Jeffcoat, 1978 (Illustration credit 13.5)

Phyllis’s injuries proved grave. The hospital staff led Hollis to believe that her friend faced three months of recuperation, and Hollis so informed Joan, who flew into a frenzy of activity to replace Phyllis’s glasses so that she could read during her long hospital stay. But, in truth, Phyllis was brain dead. The day after Jean-Paul and their friend Gabriel Illouz picked up Hollis and the French couple in Auxerre, Phyllis was taken off life support. A doctor phoned Joan, and Joan phoned her parents in Nashville to deliver the news. It was their wedding anniversary.

With this tragedy, terrible grief and confusion descended upon La Tour. How to grasp that Phyllis’s life had been snuffed out in an instant? Joan wanted her to be buried in the cemetery next door, but her parents declined, so Joan arranged for the repatriation of her body in a beautiful casket. Working with the U.S. Embassy, she also had Phyllis’s paintings shipped home, and, with her handyman Philippe, cleaned Phyllis’s apartment in Paris. Two weeks later, Philippe dropped dead of an aneurysm. The sun barely came out that spring. In July, Joan wrote Phyllis’s mother, “Do hope we’ll have some corn—and I do think it has rained every day because Phyllis isn’t painting in the garden. My I do miss her.”

Meanwhile, Jean-Paul’s knee continued excruciatingly painful, and Hollis had learned that she had sustained a serious back injury in the accident, which doctors said could heal only if she remained flat for long periods. Joan herself continued to suffer from considerable hip pain, but, stoic midwesterner that she was, said little about it. In any case, she was busy waiting on Hollis, sitting for hours in the young woman’s bedroom, alternating doses of milk and Scotch, and wavering between mothering and seducing her. Late at night Joan would flirtatiously take off her darkish glasses—“and it was really horrible looking,” remembers Hollis—to pour on the charm, and she gave Hollis massages, “concentrating on areas that weren’t even injured.” The two began a physical relationship that “was not like a typical physical relationship because [Joan] was so much in denial about it. But yes, it was all there … So it was always this back-and-forth dance about what was really going on.”

Joan’s impaired judgment and outrageous behavior that summer flagged her creeping desperation. In June, she, Jean-Paul, and Hollis attended the reception and private dinner for Sam Francis’s traveling exhibition opening at the Centre Pompidou. Seated next to Joan at the dinner, artist Ellsworth Kelly had no sooner made an obviously private remark to her than she jumped to her feet and started broadcasting it, so Kelly leapt up and tackled her. Later she laughed so hard that she wet her panties; she dashed to the ladies’ room to remove them, then returned to wave them grotesquely in the face of Fournier, who turned green. Seated at a different table, Jean-Paul ignored her, and Sam was furious, afterward telling friends, “I will never speak to her again! I’ve had it. She ruined my whole dinner.” (Later they reconciled.)

Equally tone-deaf was Joan’s insistence that Jean-Paul and Hollis spend the rest of the summer together at a clinic in the south of France, he taking physical therapy for his knee, she for her back, and both getting some sun. Perhaps this was the only way to ensure treatment for Riopelle, who feared doctors and neglected his health, yet Joan appeared to be testing Hollis’s faithfulness to her while nudging her into unfaithfulness—a way of hanging on to both Hollis and Riopelle and ensuring that she would not be abandoned.

In the south of France, Hollis and Jean-Paul did become lovers. Between the captivating young woman and crazy old Joan, Jean-Paul’s choice was easy. But Hollis too blindly plunged ahead, only later examining her conscience: “I’ve tried so often to understand what I was doing. Jean-Paul is exactly my father’s age. How could I have done this to the person I was closest to? Of course, I tried to justify it by saying, ‘Well, they’re not together, so why not?’ ” Aware that the famous love affair of Mitchell and Riopelle was vital to their self-narratives, Hollis nonetheless felt it belonged to history, not to everyday reality. Besides, she rationalized, sleeping with Jean-Paul meant little, since her real allegiance lay with Joan. Officially, Joan did not know what had happened, but when the couple returned to Vétheuil that August, “just friends” in Joan’s presence, she started pushing the idea that Hollis should have Jean-Paul’s baby and the four of them would live together, the perfect little family, at La Tour.

For the time being, however, life on the hill was dismal. In September Joan wrote her niece Poondie,

Everyone seems to have died here or on crutches (ain’t been no way amusing for last 8 mos.) and I have no dog sitter or feeder or garbage taker downer or lawn mower or weeder and I have a show Oct. 15th [at Fournier] which is nowhere (and all “my critics” died too). [That July, Harold Rosenberg had succumbed to a stroke, and two days later Tom Hess had died of a heart attack.]

All that fall, Joan and Jean-Paul—two strong, wild personalities—vied for Hollis, while their own relationship continued to molder. In New York, Joan’s pal, soap opera writer Joe LeSueur, who had long toyed with the idea of doing a roman à clef titled Messy Lives, raised his eyebrows: “All I can say is, your messy ménage à trois arrangement provides me with a nifty situation for MESSY LIVES PART II.”

Then one very early December morning, Joan, having painted all night, stumbled pie-eyed into the house to discover Jean-Paul in Hollis’s bedroom. Always up by six or six thirty a.m., he had formed the habit of bringing Hollis coffee in bed and chatting for a few minutes before he shot off to his studio. Nothing else was going on that morning. But the gesture was intimate, symbolic, and familiar from the time when Joan and Jean-Paul had been lovers. Joan howled, flew at the two, and then raged around the house in a long jealous fury, at one point scooping up a pile of Hollis’s letters to her and burning them in the fireplace.

In the aftermath, Hollis left them both, traveling to Florida, where she moved in with her mother. Joan called daily. Jean-Paul called daily. Weeks passed. Then one day Jean-Paul announced to Hollis that he had officially left Joan, whatever that meant. Would Hollis come live with him? She accepted. By January, the couple had settled at St.-Cyr.

Immediately, Joan and Hollis were back together, spending their days at La Tour, joined by Jean-Paul for dinner around eight. But afterward he and Hollis would go home to St.-Cyr. Joan was warier, nastier when drunk, and even more taunting with Jean-Paul than before: Hey, Jim, do you want to fuck me tonight? He’d respond, woundingly, God! Yet, in one letter to a friend, Joan paints this homey scene of an occasion when Hollis did stay the night: “Hollis and I are trying to push the paint around—5 am—she at one end of studio and me at other—Mozart on machine ‘Grand Mass in C Minor’ and 3 German shepherds on bed.”

As time went on, uneasiness gained upon Joan. Leaving the couple to dog-sit at La Tour, she traveled to New York that February to seek help from Fried. Shortly after her return, Jean-Paul voiced strong objections to Hollis’s spending so much time with Joan, and abruptly the couple decamped for good. The minute she realized they were gone, Joan rushed to the phone, frantically dialing friends. One of the first was Mike Goldberg in New York.

“Who are you talking about?”

“Hollis and Riopelle.”

Mike was grumpy. “You know, Joan, it’s three o’clock in the morning.” Then: “Joan, you set it up.”

She smashed down the receiver.

Mike’s phone rang again.

“HOW CAN YOU BE SO MEAN?!”

“Well, it’s the truth. You don’t send a young, attractive girl [to the south of France] with a guy like Riopelle.”

Abandoned, betrayed, humiliated, and so distraught that she felt she could not cross the street alone, Joan barely functioned. Her childhood traumas were reawakened, her worst fears realized. That she and Riopelle had no longer operated as a couple, that she had been deeply unhappy for years, that she had courted this disaster did nothing to mitigate her despair. She had been pushed off a cliff into the void. For twenty-four years, her relationship with Jean-Paul, however ugly and painful, had at least been hers. He was present each time she smelled coffee or gazed upon certain landscapes. The loss of Hollis—her daughter figure, her younger self, the most piquant presence in her life—completed the map of Joan’s mental anguish. All of Joan’s bitterness about Riopelle’s mistresses now upon Hollis.

Rattling around that big house, its emptiness and silence familiar but now terrifying because they stretched out indefinitely, Joan spiraled into depression. For weeks she holed up and drank. In any case, she had no dog-sitter. Rectangles of starkly white wall marked the spots where Riopelles had hung. Sheets shrouded the unused billiard table piled with suitcases, one always packed for New York, an inadvertent symbol of her profound unbelonging.

The drama into which Joan pulled friends when she called to rant about Jean-Paul’s defects and Hollis’s treachery was (unlike the byzantine truth) a conventional tale of a sycophantic dog-sitter/assistant who stole a weak-willed man from his rather old-fashioned Anglo-Saxon mate. Joan’s later in-person indignant explanation to poet Bill Berkson was typical: “I caught him in bed with my assistant. That was too much!” In Joan’s telling, she had kicked Riopelle out. Among the very few letters she wrote during those months of anguish were one or two to Barney: “To realize how nothing one is to someone else is hard,” she told him. “Oh God how hard,” he replied. “A murderous rage rises up in me … my sweet Juana.”