are all we have. So count them as they pass. They pass too quickly

out of breath: don’t dwell on the grave, which yawns for one and all.

JAMES SCHUYLER

Joan had been having trouble swallowing, and then, in the summer of 1984, she noticed a lingering sore in her mouth. Overcoming her fear of anything dental, she consulted Michaële-Andréa Schatt’s mother, a dental surgeon in Mantes-la-Jolie, whose biopsy revealed a malignancy. Joan was referred to a Paris hospital, where, as she had long dreaded, she was diagnosed with cancer, advanced cancer of the jaw. She was told that her jaw had to be surgically removed and replaced with a prosthesis. In a flash, everything irremediably changed.

Urging a second opinion, Gisèle contacted a cardiologist friend, who put them in touch with the Curie Institute. One day that October, Joan walked into her first appointment at Curie white with panic fear and barely able to get words out of her mouth. But Dr. Bataïni told her that radiation was an option. She soon began shuttling back and forth to Paris for every-other-day radiation treatment sessions. Side effects included enormous sores in her mouth, chronic dry mouth from the destruction of her salivary glands, and a dead jawbone, as fragile as glass. She lived on nutrition drinks and Xylocaine. For the rest of her life she would be limited to purees, soups, and other soft foods, and she had to chew slowly and carefully: she was at risk of breaking and losing her jaw. Moreover, the lower part of her face turned masklike and simian looking. Self-conscious, she would put her index finger on the corner of her mouth or use one hand to half cover her jaw, and often she joked about wearing a chador.

But the treatment succeeded. Declared cancer free by Dr. Bataïni, whom she called “God the Father,” Joan celebrated by throwing a small party for Gisèle’s thirty-seventh birthday on February 28, 1985. Their guests included Jean Fournier and “lady painters” Zuka, Shirley Jaffe, Elga Heinzen, and Claude Bauret Allard. Joan gave Gisèle an orchid. The day was crisp and cold; the sky was eggshell blue and teeming with birds.

Joan’s crisis continued, however, in that her feelings of sadness, solitude, and terror triggered by the cancer knew no bounds. Try as she did, she found it impossible to get beyond a cold, sick, white, metallic numbness. “Write down the despair,” urged Gisèle, “or, or, or … Write down everything that hurts, ou t’empêche de peindre [stops you from painting] … The total isolation must be avoided. I am alone and yet I am not … Your winter experience has been so painful, so hard—no wonder.” Joan probably did not act on Gisèle’s advice to write, but heeding Fried’s lesson that activeness is essential to mastering depression, she had found a new psychoanalyst, Christiane Rousseaux-Mosettig, whom she had begun seeing that November and had quickly come to love and respect.

A handsome, understated woman with a low, thrilling voice, this classic Freudian originally trained in philosophy fused theory with intuitive understanding, shunned French-style intellectual gamesmanship, and brought literary and artistic references to her practice. (Joan delighted in the fact that Mme. Rousseaux loved the early Kandinsky.) The two set up regular appointments on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday afternoons. Simply keeping this schedule was a major commitment for Joan, her commute from Vétheuil to Mme. Rousseaux’s office in the eleventh arrondissement, on the opposite side of Paris, entailing long taxi, train, and metro rides. Nonetheless, Joan “never missed, [was] never late, more likely early than late, [came] in every kind of weather, with every kind of flu … It was an all-out commitment … to work, to work.” And from the day she first arrived, in such anguish that the analyst felt she could not be put on the couch because she had to have a human face in front of her, Joan made rapid progress. This “doesn’t mean that she did not have large gaps, that she was not overwhelmed by depression,” explains Mme. Rousseaux, “yes, that happened all the time. But [her depression] did not preclude active interior work.” She found Joan “like a child who wants to be loved completely. I believe this was her main problem, [and] she suffered from it acutely.” At the same time Joan demonstrated a great deal of rigor vis-à-vis herself and a very intense transference.

Psychic healing also meant painting. When at last she felt able to work, Joan cast about for the right something felt and remembered her “tragic and beautiful sunflowers dying” in autumn against a backdrop of stark clouds and “the fall cool sun—that cold yellow—superb.” This memory served as the emotional trigger for her six Between paintings as well as Faded Air I and II.

That thin, brilliant, volatile yellow, in fact, dominates Faded Air I, in which Mitchell juxtaposes it à la Manet with lustrous black, along with bluish pink, orangey yam, gray, and cobalt green (an unusual semitransparent bluish green verging on gray). Both cobalt green and barium yellow were among the hues Joan “used to death” at one time or another, recalls Carl Plansky, who had begun making paint for himself and his friends, including Joan. For the emotion-color synesthete Joan, each fetish color carried its own intense meanings. Cobalt green was extremely unhappy (the metallic chemical element cobalt, used in both paint and cancer treatment—including her mother’s, her sister’s, and her own—evoking, as it did, “active death and passive death”). As for the white ground that now succeeded the alloverness of much of her earlier work in Vétheuil: “It’s death. It’s hospitals. It’s my horrible nurses. You can add in Melville, Moby Dick, a chapter on white. White is absolute horror, just horror. It is the worst.”

The lush equanimity of La Grande Vallée had vanished. Wild, beautiful, and tremulous, Faded Air I skirts chaos, the spiky scrawl of pigment on its left panel pitching diagonally toward the rising tower of scribbles on its right. Its feeling is analogous to that of Joan’s musical obsession at the time: Bach’s Cantata 78, which she loved for “the way it mounts—fabulous.”

As unsettled as Faded Air, the A Few Days (After James Schuyler) cycle of paintings brought weightless flurries of cobalt teal. The Before, Again cycle that followed (its title refers to time relations among medical appointments and procedures) churned with off-hues of yellow, blue, orange, green, pink, and black dashed with red. Joan’s upswell of painting then continued with the brutal Then, Last Time group—“death warmed over,” she said grimly—culminating in Then, Last Time IV, a menacing, twofold tidal wave of pigment, cobalt blue, and steely cobalt green.

The first time she consulted Dr. Bataïni he had ordered her to stop smoking and drinking immediately, and she had complied. Joan’s old friend, producer Joe Strick, had offered to give her “a clip on the chops if you ever think of going back to smoking,” yet, on her own, she made it, learning even to paint without cigarettes. Liquor was something else. The painting imperative to drink outweighed the medical imperative to stop, so she stayed off the hard stuff but took up white wine in a serious way. After drinking up the collection of pricey grands crus Riopelle had left behind, she made a deal with Le Hangar, a Parisian restaurant, to store their wine at La Tour and purchase from them, thus, in effect, setting up a twenty-four-hour wine shop only steps from her door.

Joan treated cancer as a test of character and courage. She still wanted to live large, act bawdy, and have fun, but often she was exhausted. She took Speciafoldine for her anemia and Carencyl for her fatigue. Moreover, with cancer literally in her face, forcing her to come to terms with mortality, she continued to battle depression. Cured or not, she figured she didn’t have many years left.

Then, just as she geared up to “paint more directly” and not “fuck around anymore,” the hip pain from which she had been suffering for years intensified. Joan had osteoarthritis resulting from hip dysplasia, a congenital degenerative condition of the hip joint, which affected both hips severely enough that she had had to move to a bedroom on the ground floor in order to avoid the stairs. It had also taken its toll on her recent work, the thinness of its facture betraying her lack of physical stamina.

Yet she had willed into existence bold eight- or nine-foot-tall paintings, working the tops by clambering up on a metal stool to place a stroke or two or three, then descending and retreating to the back of her studio to study the results before moving in again. Finally Gisèle drove into Mantes-la-Jolie and purchased two ladders, which facilitated Joan’s task but which the artist would never have bothered with on her own. From Joan’s point of view, you just got up and did it: “Keep cracking! Don’t get discouraged. Just a waste of time.”

In December 1985, Joan underwent hip replacement surgery at the Hôpital Cochin in Paris. She had a big emotional investment in this operation; it might have marked a turning point in her mental state. But it proved largely unsuccessful, leaving her in despair and pain, which she self-medicated with Chablis and Sancerre. Friends who visited her at the hospital smuggled in vast quantities of wine under their coats, tokened by the army of empties lined up next to her bed.

Transferred to a clinic in suburban Louveciennes, Joan fell in love with the trees she surveyed from her window. There, during three weeks of recuperation and therapy, she did watercolors for the first time in years. (Artist Malcolm Morley had given her a few tips.) “When I was sick,” she later remembered,

they moved me to a room with a window and suddenly through the window I saw two fir trees in a park, and the grey sky, and the beautiful grey rain, and I was so happy. It had something to do with being alive. I could see the pine trees, and I felt I could paint. If I could see them, I felt I would paint a painting.

Back in Vétheuil, one day several months later, Joan sat outdoors and watched her oils being removed from her studio and loaded into a truck for shipment to New York “and the trees and the garden were beautiful and there was a beautiful light and I saw the painting moving. A big strong man moved them with great ease and I saw all their colors behind the trees moving and it was like a parade and I was happy.”

By the mid-1980s, a single-panel Mitchell sold for $30,000 to $40,000 and a multi-panel Mitchell for $50,000 to $100,000. Hanging in Fourcade’s foyer during her show that April, the colorful A Few Days I and II (For James Schuyler) were snapped up, and gallery-goers kept approaching the reception desk to ask if there were more like the two near the door. Virtually everyone saw A Few Days as cheery, a viewpoint that amazed Joan: “Only one person got death. So strange.” The rest of the show did not sell particularly well, though San Francisco Bay Area collectors Hunk and Moo Anderson bought the powerful Before, Again IV, and film critic Gene Siskel and his wife Marlene fell under the spell of a Then, Last Time painting. They mulled it over for a long while but finally chose one of the Grande Vallée works from Jean Fournier. The two were bitten by the Joan Mitchell bug, remembers Fourcade’s assistant, Jill Weinberg, “just completely!”

The show had gotten underway with Xavier’s usual convivial dinner party for Joan’s friends, but most of the artist’s socializing revolved around the suite at the Westbury Hotel, on East Sixty-ninth Street, where she had been staying since losing St. Mark’s and where she held court each afternoon. The phone jingled, white wine flowed, old friends and art world emissaries filtered in and out, mingling with the artist’s young protégés, who now included Cora Cohen, Billy Sullivan, Rebecca Purdum, Peter Soriano, David Humphrey, and many others. Laughter rang out, friendships were born, jealousies flared. Often the artist swept her entourage off for roving studio and gallery visits. Her hip condition and fatigue cramped her style—she could no longer negotiate steep stairs, nor could she stand for more than twenty minutes, and she needed a cab for even a short distance—yet, leaning on her cane and flanked by young friends, she hobbled into an opening here, a restaurant there. When she ran into Helen Frankenthaler at One Fifth, Joan slyly insulted her by feigning to mistake the artist for her older sister, and once she verbally flogged her niece Poondie, who had flown out from California to be with her, until Poondie stood weeping on the sidewalk. Yet another time (notwithstanding fellow guest Hal Fondren’s talent for defusing her outbursts with an affectionate “Oh, Joan, shut up!”), she roiled Joe LeSueur’s dinner party in her honor with rabbit-punch accusations that “the New York fags” were “ganging up” on her. No, Joan had not mellowed. Indeed, scared by her own decline, she proved more pugnacious than ever.

Joe LeSueur with his Mitchell at his Second Avenue apartment, c. early 1980s (Illustration credit 15.1)

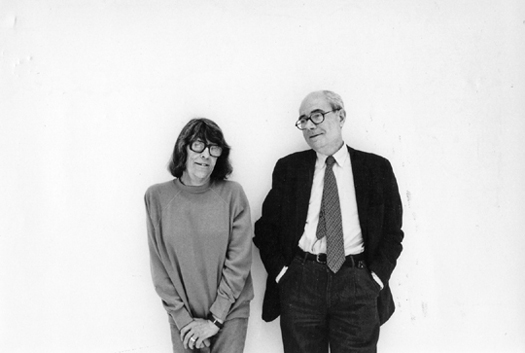

With her longtime French dealer Jean Fournier, dubbed “Quai d’Orsay,” c. 1987 (Illustration credit 15.2)

Back in France that rather lonely summer, big Joan was temporarily retired as little Joan struggled with the psychological and physical difficulties of postoperative painting. She worked small, using an easel for the first time in four decades, with her paints and brushes laid out on rolling tables rather than on the floor. This arrangement hardly afforded the direct registration of bodily movements to which she aspired, but it was the best she could do. Worked less muscularly than usual, her River cycle, which evokes consciousness and time, managed nonetheless to effect the surging, scrambling, rampaging paint/water she so loved. As her strength returned, the paintings grew larger.

Despite her joy at once again striving for pictures, the emotional climate at La Tour continued dismal, all the more so because the elderly Iva was failing. Joan’s German shepherd—her bedmate, baby, alter ego, companion, and muse—had for thirteen years sat sphinxlike next to her daughters, Marion and Madeleine, on the studio daybed as the artist worked. Sometimes the dogs pissed on her paintings, which Joan found hysterically funny; sometimes she got them to paint with their tails.

Iva died on September 25. Attempting to make positive sense of this fresh heartbreak, Joan wrote to Joanne and Phil Von Blon,

All all my memories of [Iva] are so full of joy. I feel lucky to have known her or whatever or experienced her or that—let’s say—she allowed me to sleep in her bed or live in her house. What a lovely dog. Her “puppies” are confused but I’m trying to be the “lead dog.” Who said “only the lead dog sees the landscape”? I dig that statement.

In another tremendous blow, Xavier Fourcade revealed that he had AIDS. Having learned of his condition several months earlier, Joan’s New York dealer had grown a beard to cover the sores and kept the illness private as long as possible. Only in the early fall of 1986, as he was leaving for France to pursue an experimental therapy involving blood exchange, had he told his employees and artists. The news forged a closer bond between Joan and the gallery staff, including Jill Weinberg: “We had this shared, deeply, deeply fraught concern. She was just devastated. There was a really horrible, horrible and wonderful, sharing of grief and loss and fear.”

Joan and Xavier saw each other often that fall. By December, it was obvious that the French treatment had failed, and Xavier, suffering from chronic respiratory problems and intense pain, was preparing to return to New York. As a way of saying adieu, he and Joan traveled to Lille to view a traveling exhibition of works by Matisse from the State Hermitage Museum in Leningrad. En route they stopped at Beauvais to visit the cathedral, the nave of which had collapsed in the thirteenth century when its builders overtaxed the technology in their attempt to create the most resplendent of houses of worship. Each intensely aware of mortality, the two stood shoulder to shoulder in “that crazy late Gothic unfinished superb nutty monument to God.”

The other highlight of their excursion was seeing Matisse’s 1909–10 La Danse, a thirteen-foot-wide oil on canvas commissioned (along with its companion, La Musique) by a Russian collector for his Moscow home. This Dionysian painting depicts an edge-to-edge circle of five nude dancers, their dark red bodies pulsing and taut against a sapphire blue sky and emerald green earth. La Danse radiates aliveness and joy. One’s eyes find no resting place, one’s whole physical being is swept into a ceaselessly turning energy.

Joan had first viewed Matisse’s masterwork at the artist’s 1970 retrospective at the Grand Palais, from which she had emerged weeping with emotion. Later asked which work of art she would choose if she had to live with just one, Joan had replied that she would “take the whole dance-and-music scene of Matisse, those great big murals with the fabulous greens, reds, and blues.” Joan’s love of La Danse had made itself felt in past work, in the buoyant circularity of her enormous 1983 Grande Vallée triptych, for instance, and would do so again in the tondos (round paintings) with which she experimented in the late 1980s.

Now, her lyrical Lille cycle, created after Xavier’s departure, swarmed with knots of intense color, their motion (as the artist put it) “made still, like a fish trapped in ice.” Consisting of an activated, edge-brushing core floating on a white ground, the diptych Lille V is moving and still, opulent and tough, structured and free—in other words, classic Mitchell. Later that spring, the Lille group gave way to the Chord paintings—canvases freighted with the knowledge of Xavier Fourcade’s death on April 28, 1987, at age sixty—their wheeling, lurching coils of pigment underpinned with black, risking dissolution at any moment, equal parts convulsion and dance.

On June 10, Joan’s seventh show opened at the Galerie Jean Fournier, accompanied by a small catalog in which Yves Michaud wrote,

It is a fact that the last three years of Joan Mitchell’s painting cannot be disassociated from a number of serious threats and a great deal of reevaluation: personal physical setbacks, threats upon herself felt as a result of the loss of loved ones, an increase of aggression and distress in reaction to these attacks. To all of this, painting is more than a witness: it is the ground on which the confrontation takes place, on which the crisis is resolved.

The previous winter, in New York, Joan viewed another inspirational exhibition, the Metropolitan Museum’s Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers. She then went home and painted No Birds, a work haunted by the Dutch artist’s Crows over the Wheat-field, done in Auvers-sur-Oise, only twenty-five miles from Vétheuil. (Her love for Crows over the Wheatfield was hardly new, however. Thirty years earlier, she had written to Mike Goldberg, “Color sends me more than ever and Van Gogh and his crows.”) Mythologized as the painter’s last work before he shot himself, Crows over the Wheatfield depicts three roads fanning out to nowhere in a roiling ocean of golden grain as frightening low-flying crows, a traditional symbol of death, sail out of a claustrophobia-inducing stormy-blue sky. Heavily invested with feeling-memories of Crows over the Wheatfield, Mitchell’s No Birds also adverts to its predecessor’s structure, spatial syntax, graphic strokes, and palette (though Mitchell springs the surprise of a tender pink). In her work there are no birds—nor are there, of course, fields or sky—only speeding, slashing ribbons of black that register as ominously and frenziedly as any flock of crows.

Why did Joan single out Crows over the Wheatfield, a painting popularly interpreted as a kind of suicide note and bound up in the mythology of van Gogh’s suffering, self-destruction, and transcendence? (That year, she titled another diptych Ready for the River—meaning suicide, she bluntly informed Robert Harms. Then, making light of her own life-and-death references, she added that for weeks she had heard a birdlike noise in her studio, which turned out to be only a loose tile rattled by wind, hence No Birds.) Without a doubt Joan had given serious consideration to ending her life. But if No Birds alludes to suicide, this marvel of painterly self-confidence and intelligence also speaks of painting as “the opposite of death,” as vibrant, bristling, ripe aliveness. Joan was never one to gloss over emotional dilemmas or fear collisions, on canvas or in life.

No Birds is also, of course, an homage to Vincent van Gogh. For reasons Joan could not begin to articulate, the supremely felt paintings of “Vinnie” had “stayed with” her since the age of six. She responded to their “fanaticism,” their spirituality, and their vibrant sense of place, her reaction to Vétheuil having been on the order of his to Arles. Sunflowers, skies, fields, and trees—not least, cypresses—deeply affected both artists, and both projected themselves onto trees. The two felt color intensely and carried myriad colors in their mind’s eye. Moreover, both experienced painting as (in the words of one letter from Vincent to his brother Theo) “a way to make life bearable.” (Joan owned and treasured a volume of van Gogh’s complete letters.) Only painting, as Fried used to say, afforded van Gogh the means to contend with the flood of feelings that threatened to engulf him, which was Joan’s case as well. Highly self-critical, she never put herself in the same league as van Gogh, but he, along with Cézanne and Matisse, represented the highest standard of painting, to which she aspired.

The formal lessons Joan learned from van Gogh were myriad. Some had to do with his vigorous dabs, stabs, and swirls bodying forth energy and growth while manifesting paint as paint. Others related to his use of space: the frontal, tipped plane of his House at Auvers, for instance, and the color-activated space in the floor in the Musée d’Orsay version of Bedroom in Arles. Like van Gogh, Mitchell took full advantage of complementary and near-complementary colors, expressing, as he put it, “the love of two lovers by a wedding of two complementary colors, their mingling and their opposition, the mysterious vibrations of kindred tones.” Both artists favored blues and yellows or yellow oranges, working them in crafty ways, Joan, like van Gogh, tucking a few strokes of orange into a corner, perhaps, rather than placing it next to the blue, thus setting up a dynamic pull that made her work sing.

Having revolved around one man, the Xavier Fourcade Gallery was closing, a process which required about a year and entailed the search for appropriate representation for each of its artists. Mitchell ranked fourth or fifth in terms of desirability. Edging toward establishing a gallery of their own, Fourcade’s director (and lover) Bernard Lennon and assistant Jill Weinberg were eager to represent her, and the artist was willing, but plans were slow to fall into place and the consensus was that she should not remain too long without a dealer. Thus she visited various galleries, including Robert Miller at Fifty-seventh and Madison, where she loved the light and high ceilings and hit it off well with Miller, who liked her “rugged individualism.” They quickly came to an agreement that the Bernard Lennon and Robert Miller Galleries would jointly handle her work. (After Lennon too died of AIDS, on Thanksgiving Day 1990, Mitchell was represented solely by Miller.)

Larger, more assertively stylish, and higher profile than the Xavier Fourcade Gallery, the Robert Miller Gallery focused on painting and photography. Interested in one-of-a-kind artists, undervalued or not, many of whom were women, Miller represented Alice Neel, Lee Krasner, Louise Bourgeois, Bruce Weber, Robert Mapplethorpe, and the Estate of Diane Arbus. Irreverently dubbing it “the fags and females gallery,” Joan was delighted to be at Robert Miller and on Fifty-seventh Street, the home of prestigious galleries since her Tenth Street days.

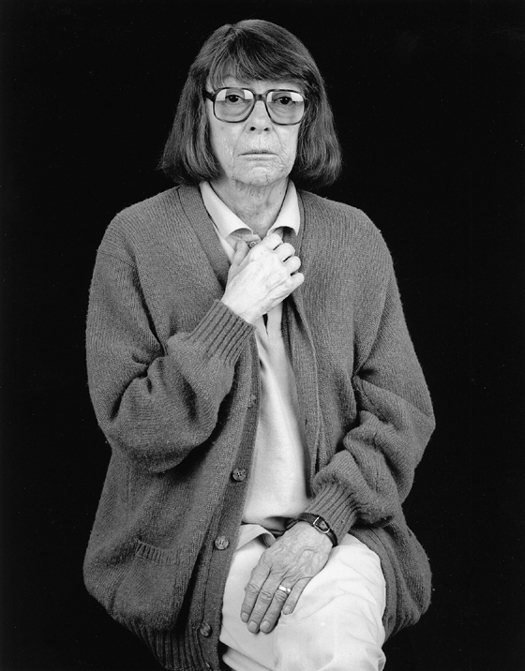

Not long after joining Miller, Joan was asked to pose, as had other gallery artists, for photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. She disliked the idea of having her picture taken, but nonetheless agreed, showing up at the appointed time at Mapplethorpe’s Twenty-third Street studio having traded her usual shapeless and unflattering garb for more style-conscious pants, polo shirt, and mannish cardigan. In one of the resulting pictures, the quintessential image of the aging Joan Mitchell, the painter is isolated against a starkly black background. Her left hand rests on her thighs; her right obeys an impulse to hide by pulling together the opening of her shirt. Her fading, well-behaved pageboy, little nose, withered jaw, and sad eyes framed by tinted lenses lend her the air of an elderly child, but the singularity of Mapplethorpe’s photograph lies in the artist’s expression of grievous concern. Mapplethorpe too had AIDS (he would die the following spring), and the click of his shutter coincided with Joan’s full emotional recognition of that shattering fact.

By the time Mitchell joined Robert Miller, preparations were well underway for her first retrospective, guest curated by art historian Judith Bernstock for the Herbert F. Johnson Museum at Cornell University with seed money from the National Endowment for the Arts. Accompanied by a two-hundred-plus-page catalog that comprised a substantial artistic biography focused upon her painting’s relation to poetry, it would travel to museums in Washington, D.C.; San Francisco; Buffalo; La Jolla, California; and Ithaca, New York, but not, as she was acutely aware, to more prestigious venues in, say, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, or New York City.

Wasn’t Joan pleased about the exhibition? Yes and no. At first she had bridled at the idea of a retrospective, which she viewed as a funeral of sorts, and had sent word via Yves Michaud to Cornell museum director Tom Leavitt that she objected to being “art-historized live.” “It’s horrible,” she harrumphed to one well-wisher. “It’s like having nails put in your coffin. But I think if you’re offered a show, you do it, no?” Savoring the idea of a big exhibition, on the other hand, she approached the project with characteristic imperiousness and intensity. Jill Weinberg, who shepherded the project from the Lennon Gallery side, had ample occasion to observe artist and curator in action: “Joan really challenged Judith. She yelled at her. She instructed her. She gave her books to read. She disagreed with her. She agreed with her. Joan … was reluctant to acknowledge the curator’s judgment and prerogative to make a selection of paintings.” Out of this difficult and painful collaboration came the choice of fifty-four paintings, from the 1951 Cross Section of a Bridge to the 1987 Chord VII, Joan having nixed the usual inclusion of a few examples of student work. Nor did the show comprise drawings or prints.

A portrait by Robert Mapplethorpe, who has just told Joan that he has AIDS, 1988 (Illustration credit 15.3)

Joan was equally unwilling to defer to museum staff expertise. No sooner had she hobbled into Washington’s Corcoran Gallery of Art one day in late February than she began demanding changes in the installation in progress. Moreover, displeased to find Sunflower, on loan from Pierre Matisse, hanging a bit limp on its stretcher (it had been rolled for many years), she ordered a bucket of water and a sponge (wetting the back of a painting tightens the canvas) and would have put former Fourcade staffer Tom Adams to work. But the installers and registrar objected. Artists do not walk in and start improvising treatments to the art. There are procedures. However, Joan put her foot down. In the end, Matisse was called, and she got her way.

Opening events at the Corcoran were marked by Joan’s reunions with old friends and admirers, notably a two- or three-hour tête-à-tête with her childhood pal, anthropologist Robert McCormick Adams, now the head of the Smithsonian Institution, and a lavish dinner party at the home of collectors Ann and Gilbert Kinney. Rather formal in manner, the Kinneys (she was an economist, he the head of the Archives of American Art and heir to the Kinney Shoes fortune) owned a very fine mix of art, including Bonnard, O’Keeffe, and Mitchell. Even a whiff of Social Register pretentiousness inevitably brought out the devil in Joan, however, not to mention that she was the worse for innumerable glasses of wine. Thus the sixty-three-year-old guest of honor tottering around with a cane could be observed that evening throwing chicken-in-cream-sauce hors d’oeuvres at someone, chewing out President Carter’s former national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and asking an African American guest if he was a token black, before turning to her hostess: “What the hell kind of waitress are ya? This place is a dump!” Everyone heard. The room suddenly grew silent. It was painful. Her handlers could not get Joan to leave. She wanted another drink.

Two months later came San Francisco’s turn. Housed at that time on two floors of the War Memorial Veterans Building, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art could not accommodate the entire retrospective, which had to be pared down to thirty-six paintings. When Joan arrived and took in this situation, she went ballistic, giving the curator hell too for a “very messed up installation.” For good measure, she railed at the museum for simultaneously showing the work of art star photographers Doug and Mike Starn, which she scorned as trendy and shallow.

Other memorable San Francisco moments came at Harry’s Bar, across the street from the museum, where Joan held court with two curators, her niece, and her dealer Robert Miller as Los Angeles Times art critic William Wilson attempted an interview that more than once left him “lapsed into defeated silence.” At one point, the painter needled the curators “about some minor disagreement between them,” writes Wilson. “Apparently the female curator had given in to the handsome male on some aesthetic point. Mitchell told the female curator she was a nice typical girl masochist. As the conversation progressed, the artist promoted her to a Major Masochist and then a Major Mormon Masochist.”

Sometime after her second Bloody Mary, Joan fished a letter out of her bag: “Know what this is? This is from the first man who ever fucked me.”

No one knew what to say.

“ ‘Oh. Fascinating. When did you last see him?’

“ ‘Um. 1950.’

“ ‘My. How old were you when, you know, it happened?’

“ ‘Eighteen.’

“ ‘Good age.’

“ ‘It wasn’t considered proper back then. The kids start even younger these days. You people have kids. They do it?’ ”

That long-ago lover, painter Dick Bowman, who lived near San Francisco, had been invited to the opening reception and dinner. Spotting Dick soon after he arrived at the museum that evening, Joan limped over, hugged him, and then embarrassed him by grabbing his crotch. Eventually the two found a bench, she lowered herself onto his lap, and they settled in for an affectionate talk.

The following evening, an event billed as an artist’s lecture again put Mitchell’s cantankerousness at center stage. Joan having, in fact, declined to lecture, her old friend poet Bill Berkson spoke of poetry in relation to her painting, after which the artist fielded questions. As usual, she did not scruple to insult her admirers, responding to the first query with an abrasive “What kind of dumb question is that?” Others got similar treatment. People turned scared. Finally someone brought up Hans Hofmann, and Joan spoke effusively of Hofmann as a great teacher. Afterward, one member of the audience approached Berkson: “My! You certainly had a tiger by the tail!”

Joan’s reviews were generally positive, with reservations centering on the prettiness of the early 1980s work and a certain sameness of feeling. Some considered Joan’s art in the context of Neo-Expressionism, but she dismissed most Neo-Expressionist work, especially that of David Salle, accusing one friend who owned two cats and a Salle painting of animal abuse. Indeed, the retrospective format of her exhibition illuminated the enormous difference between the slow, organic maturation of what New York Times critic John Russell termed Mitchell’s “grown-up painting,” on one hand, and art created in the context of a market-driven art world, on the other. Joan detested the star system. (Another bête noire was painter Jennifer Bartlett—“Miss Hollywood,” in Joan’s parlance—whose shows at the Paula Cooper Gallery had dazzled the art world in the 1970s.)

Painters who pursued a focused discipline over the course of a lifetime having grown ever rarer, Joan, the gruff Pasionaria of painting, attempted to rally the young, as during her question-and-answer session at the New York Studio School that spring. There are no more painters, she insisted, only object makers, installation builders, and cartoonists. Nor are there worthy viewers of painting. People just watch TV. But you! Be a visual painter, be a serious painter! You have problems, you have people to support—okay, who doesn’t? All the same, paint, paint!

Despite her insistence that painting was its own reward, Joan had been fretting about whether or not she had made her life a success, which part of her still defined as winning trophies. That year she received the first Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement from the College Art Association, was named Commandeur des Arts et Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture, and accepted an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Accompanied by Jill Weinberg, Joan traveled to Chicago for the first time since her mother’s death, to receive her diploma. She now routinely dismissed Chicago as the “most racist city in the world” yet she had fiercely defended it to one French critic who had not attacked it: “You think that in Chicago there are nothing but savages, but in Chicago is the greatest collection of Rembrandt drawings.” This short visit afforded her a kind of emotional reconciliation with her hometown. In the hours preceding the graduation ceremony, she and Jill had settled into an empty bar not far from the Art Institute. Jill recalls that they

sat in a red leatherette booth beside a dusty plate glass window giving us a view of a perfectly ordinary slice of downtown Chicago. There we sat for hours, and Joan spoke about Chicago and how it felt to be there. She described Chicago as hard and male, a town of testosterone, brutal and beautiful in equal measure. Joan had left there long ago, but it had not left her. I think Joan found herself unexpectedly excited to be there.

She would never return.

As Joan’s artistic reputation grew, her health continued to deteriorate. Facing a second hip replacement, she alternated between crutches and a walker. Arthritic pain was now flying through her hands as well, making it harder to hold her brushes. She joked about having them strapped on as Renoir had in his old age. Because she had no saliva, she had to gargle and rinse constantly. And her glasses got thicker and thicker. She was sick and tired of pain, doctors, medical procedures, hospitals, and the human condition. Yet she demonstrated, in the words of her cook, Raymonde Perthuis, “formidable valor” and “an iron will,” and she never complained, though her suffering and fatigue easily triggered aggression.

Quicker than ever to test and judge others, often unfairly, Joan left a trail of hurt feelings behind her. A visit from her old friend artist Marilyn Stark degenerated into an angry tirade from Joan because Marilyn, a widow with two children to support and nothing like Joan’s fortune, was not painting full-time. (Having never worked for a paycheck, Joan had little idea of most people’s financial realities.) One hard-of-hearing friend was introduced to others as “deaf, as in deaf and dumb.” Another, arriving at La Tour, after a hiatus of several years, looking hefty and every bit her age, heard, “What happened to you?” The minute she detected a spot of insecurity or guilt, Joan was “putting in the dagger and turning it.” Warm and loving one minute, she could turn angry and ugly the next.

What others experienced as grossly insensitive behavior, Joan meant as communicating in an essential way, forcing them to see themselves honestly and fully. Life was precious, and time was short, short: one doesn’t have the luxury of coolness and detachment. Yet, even granted what one friend calls the “sweet instinct behind her murderous behavior,” it’s difficult to square that murderous behavior with Joan’s astuteness about people’s psychological workings. When they rejected her and she sensed she wasn’t loved, says Mme. Rousseaux, Joan acted “like a baby who falls into a rage,” and she too suffered intensely from her conflictive relationships.

At the same time she swept those around her into her fierce engagement with living. She made Robert Miller’s gallery director John Cheim

feel like an elated youth, back in school, adolescent. With her everything was interesting. Truly democratic, a conversation with a stranger as drawn out by Joan would turn fascinating—making one realize what a snob one was and how much of life one missed. Joan missed nothing. If she was sometimes cruel, at least she was accurate, always bringing to the fore what was kept hidden, examining it, getting on with it.

Witness too Joan’s disarmingly unaffected tone in initiating a friendship with American artist Sara Holt, who lived in the building where Mme. Rousseaux had her office. One day Sara retrieved a note from her mailbox:

Dear Sara Holt, Our mutual friend Katy Crowe mentioned you to me a long time ago and also Shirley Jaffe and Zuka.… Anyway, I’m in your building 3 times a week (see a shrink Mme. Rousseaux) and I thought it would be nice to have coffee … If you feel like it, you could call evenings and let it ring or Mon or Thurs afternoons or evenings. Perhaps we could make a date … I’ve heard lots of very nice things about you and your work, and I would love to meet you. Sincerely, Joan (I paint.) Fournier Gallery.

Sara phoned, and, over studio visits and lunches in Paris and dinners and long talks in Vétheuil, a friendship unfolded. With both Sara and her husband, artist Jean-Max Albert, Joan showed herself the soul of openness, warmth, and generosity:

Sara—Jean-Max, Wednesday—12:45. Stopped to invite you to new pizza place you talked about. I’ll be there if I can find it until 1:45. I should have called. Love, Joan.

Kids … I really love your plural work and natch both of you. So nice liking the work and the artists too—it’s rather rare I have found … I’m very very happy … The café was fun. Love, love, J.

Joan purchased Sara’s and Jean-Max’s art, recommended doctors and dentists, loaded them up with tomatoes from her garden, and urged “anything I can do, please let me know.”

And when her friend Jeanne Le Bozec was struggling with cancer, Joan phoned virtually every day. In fact, Jeanne found Joan kind in every way except to herself. Once, at Vétheuil, the artist casually mentioned to Jeanne and her husband Jean that she had a little package for them, then sent Gisèle to fetch a beautiful diptych. (Joan was in the habit of giving friends paintings, often worth tens of thousands of dollars. Because they could never reciprocate, some hesitated to accept; others, as Joan was well aware, took advantage. Unlike many artists, she kept no records: to this day, important works are scattered or lost.)

On the other hand, friends from the old days who had not seen Joan for a few years were frequently shocked by how she had changed, not for the better. Now in his late thirties, Rufus Zogbaum, who had always considered Joan “a beacon of truth,” visited La Tour and found her mean-spirited, grotesque, and humorless. It was Joan against the world. Even the house had an aura of coldness. Sculptor Marc Berlet, also virtually family back in the 1960s, now set foot in Vétheuil for the first time in ages and had a similar reaction. As Joan was showing Marc around her studio one late night, he reached to turn a canvas away from the wall, the gesture of a fellow artist and former studio assistant who had once regularly handled Joan’s work, even walked on it, as artists do in their studios. She exploded, “What the fuck do you think you’re doing!” Joan herself was casual about taking care of her work—her last painting didn’t interest her much, her next painting did—yet no one, but no one, touched it without her approval. Berlet was shocked to be treated almost as if he were trying to steal something. He stalked out of La Tour at three a.m., quite certain that Joan was paranoid and that their friendship was dead.

It’s true that La Tour’s relative isolation had done Joan little good. Barney too, to continue this triage, found her “depressed” and “sinking.” Accompanied by his companion, Astrid Myers, and his assistant, Hyehwa Yu, he lunched with Joan in Vétheuil that December. Over the years, the two had remained close, Joan signing her letters to Barney “All my love,” and each more or less always coming through for the other. This meeting, however, started off badly. Irritated that the trio had arrived late for lunch, Joan raised her voice in irritated response to some comment by Astrid, thus setting her dogs to yapping. So Barney picked them up by the ears, one by one, and carried them out of the house, at which Joan flew into a rage, especially when Hyehwa laughed at the sight. The bad-tempered mood of this very last time Joan and Barney would ever set eyes upon each other prefigured an ugly episode six months hence.

Nearly four years earlier, in 1985, Barney had sold the financially shaky Grove Press to millionaire entrepreneur Ann Getty and British publisher George Weidenfeld. Later, after the two unexpectedly ousted him, he had founded Blue Moon Books to publish Victorian erotica. In a conversation at the Westbury around that difficult time, Joan had assured Barney that he could count on her, no matter what. Now, in 1989, he took her up on it, asking by phone if he could borrow $50,000. As it happened, Joan had just regularized her situation with the French government, which meant paying a cool million in back taxes. Be that as it may, her refusal was not straightforward but arrogant and accusatory. Thus, at eleven thirty p.m. on August 2, 1989, over a rum-and-Coke at Reilly’s Bar at Third Avenue and Twenty-third Street in New York, Barney scrawled a long bitter note to Joan, which nonetheless ended, “But above and beyond all else, Joan, … you have meant a—not measurable—force in my life which cannot be belittled and destroyed by the other day. I went to you as a last port. It turned out to be the wrong place. Well, you CAN’T stop me from loving you until I die. So there.” Unmoved by his words and by nearly fifty years of unremitting love, Joan, for reasons only she could elucidate, labeled Barney “nuts” and effectively ended their relationship.

Often her ire descended upon men. While she had many male friends—she loved men!—Joan harbored a deep rage over gender politics in the art world. Years of bitter resentment epitomized by Riopelle’s past eclipse of her, in terms of collections, exhibitions, prizes, and prices, had convinced her that, in any partnership between a male and a female artist, the male would trample the female. She became, if not a feminist, a gender warrior. Thus when artist Kate Van Houten, staying at La Tour during the summer of 1990, hosted her husband, artist Takesada Matsutani, Joan made no bones about disliking Takesada and wanting him to leave “because [as Kate eventually figured out] he was a man artist [and] she was convinced I was being eaten up by him.” Joan also attempted to break up Sara and Jean-Max, for Sara’s sake. Her behavior grew erratic, her manner nasty and superior (“Well, I am Joan Mitchell”). She had an ax to grind, and she kept grinding it. Eventually, the couple’s relationship with her painfully ended.

Increasingly, Joan relied on “lady painters” for emotional sustenance, especially younger “lady painters” like Claude Bauret Allard, Michaële-Andréa Schatt, Monique Frydman, and Mâkhi Xenakis. Although Joan encouraged these protégées’ work in every way, at the same time she appeared almost misogynist. Bitter about her own lack of recognition and determined that they should be able to defend themselves, she often attacked, like a demanding trainer putting her novice prizefighters through heavy workouts in the ring. At other times, she was protective, occasionally reaching over to put a hand on someone’s arm in a surge of tenderness. With Monique Frydman, she proved unfailingly sweet and solicitous. For Monique, Joan

truly sought to understand the other person. She had several ways of going about this. She could either do it in an extremely provocative, aggressive, and brutal manner to try to shock the person out of his or her reserve. Or she tried in a much milder and more tender manner, which was my case.

One afternoon, for instance, Joan telephoned Monique: the light in Vétheuil was murky, she complained, which discouraged her from painting.

“And you, Lady Painter, how are things going?”

Frydman normally worked in pastels, a medium she possessed in a manner truly her own; in contrast, she struggled with oils.

“Doubts about my work.”

Joan responded: “Come on, Monique, give me your dogs Doubt and Melancholy. I’ll take care of them, I’ll keep them. But you: Be at ease, paint, work, turn your [old] paintings to the wall, go on to the next one. Paint!”

Over the years, Joan had spoken only rarely and elliptically about her perceptual otherness, once mentioning to Jaqui Fried, for instance, that Gisèle’s concert “was very moving—massive sound—marvelous rich colors,” once bragging a little to Joanne Von Blon that she was able to “spin back [one of their afternoons together] in my head. It’s fun.” Questioned about the generative aspects of her art, she asserted that she worked from photographs packed in a mental suitcase, a statement people accepted as valid metaphor. Beyond that, her comments sowed a certain confusion. As curator Jane Livingston puts it,

She kept insisting that feeling a place, transforming a memory, recording something specifically recalled from experience, with all its intense light and joy and perhaps anguish, was what she was doing. She seemed to assume that everyone would understand what she meant. At the same time, she was aware, disconcertingly so, that her verbal communication left most people at a loss.

During the summer of 1989, however, Joan accorded to Yves Michaud the second of two interviews (the first had taken place in 1986) in which she opened up about not only her painting but also her synesthesia and eideticism (although she did not command those words or concepts). In response to Michaud’s “You seem to me to have a strange attitude regarding words and language?” she declared that sky is red (S), gray blue (K), and yellow (Y), thus, to her, the sky was a mixture of those colors.

Michaud stopped short: “I’m lost.”

“I don’t know. That’s how it is.”

Joan had previously explained to Michaud that she imagined her own identity as “a sort of scaffolding made of painting stretchers around a lot of colored chaos,” thus suggesting the centrality of her synesthetic experiences in her self-concept, that is, her art.

Joan also broached the topic of her 1983 visit to the Manet retrospective in Paris, which had included paintings long ago fixed in her mind: “My sister had just died and a friend of mine’s cousin had just died and it was terrible, but seeing all those paintings, some from my Chicago childhood, with all that silence and no time involved, no terminations, was wonderful. There was no sadness, no death. It was still.” Her words suggest how eidetic remembering, a kind of virtual reality, collapses time and space. No doubt her experience resembled that of synesthete and eidetiker Vladimir Nabokov. For Nabokov, writes historian Kevin Dann,

the images of his past perennially ready to be recalled for his artistic purposes, never did lose any of their luster. In conjunction with his remarkable linguistic [substitute: “painterly”] gifts, his synaesthesia and eideticism kept him in the green garden of childhood, forever returning to the halcyon days when the world was still largely of his own making.

Freighted with the knowledge that her way of experiencing the world was marvelous yet “wrong” and, in any case, distrusting words and knowing that attempts to explain would meet with deep skepticism, Joan rarely tried. “At some point we [synesthetes] learn that most people do not see what we see and that our perceptions are considered, at best, ‘imaginative,’ and at worst ‘looney’ or even suspect,” writes Patricia Duffy of synesthetes’ lack of validation. “Much of the world does not see what we see and is not convinced that we see it ourselves.”

Duffy, of course, writes from the position, unknown to Joan, of one aware that her condition is named, normal, and shared. Many synesthetes experience that discovery as powerful catharsis. Some laugh and cry, many bask in their new knowledge, most feel vindicated. One synesthete has described finding out as akin to the moment when, for the nth time, the blind and deaf child Helen Keller placed one hand under a stream of cool running water while her teacher Anne Sullivan used the manual alphabet to spell “w—a—t—e—r” on the other. All of a sudden, Helen got it! Her face lit up. Everything changed. This has a name!

Never to know that experience, Joan sought validation chiefly through art, gravitating to writers and artists like Rilke, von Hofmannsthal, Eliot, Kandinsky, and van Gogh whose work appeared to attest to the soundness of her sensorial perceptions. She adored Beckett’s Embers in part because of the way in which its character’s inner and outer life, present and past, draws breath from colors and sounds. She was fond too of nineteenth-century French poet Arthur Rimbaud’s sonnet “Vowels,” which begins: “A black, E white, I red, U green, O blue: vowels, / One day I will tell your latent birth.” (“I am like Rimbaud,” Joan used to tell Michaële-Andréa Schatt.)

Finding common ground with other synesthetes might have stemmed the implacable loneliness that had her lamenting to Jean Fournier, “I am always alone.”

The summer of 1989 found a French painter couple, Philippe Richard and Frédérique Lucien, former students at the École des Beaux-Arts, installed at La Tour. Tight with Frédérique, Joan often ragged Philippe about male privilege, yet she engaged him as her studio assistant. That summer she also befriended the young American artists-in-residence at Claude Monet’s onetime home in nearby Giverny, inviting them to Vétheuil for a “magical evening” at her local restaurant, La Pierre à Poisson (where she would often insist that the waiters too, now old friends, have a glass of wine). She took a particular shine to photographer Sally Apfelbaum, who created lyrical, layered images of gardens. Suddenly invited to La Tour for lunch or dinner virtually every day, Sally found Joan disarmingly attentive and exceptionally generous to the young artists in her thrall, introducing them to others, buying their work, and making sure they got fancy French desserts. Joan proved so lively and funny, thought Sally, that people didn’t realize or forgot, except perhaps when she cradled her jaw or reached for her walker, that often she was in atrocious pain.

Trying to ignore her infirmities, Joan felt a new surge of creative energy, responding positively to an old invitation from an agency of the Ministry of Culture to create a stained glass window for the Cathedral of Nevers, in central France (unfortunately, this never happened) and, painting in the grand Mitchell style, wrapping up her first show for Robert Miller. Maelstroms of blues and greens, her twenty-seven paintings, many of them multi-paneled works, ranged up to fifteen feet wide. Aware of her condition, friends gasped: How did you manage physically? The painter would shrug—Joan at her best—“Ah, you gotta hack it.” Get up on “that fucking ladder.” So what if you’re tired or unwell. Try again. Something you still haven’t gotten quite right? Then get cracking. Painting remained a mystery as well as a joy.

Having watched Joan make the slow, painful trek up to her studio again and again, Sally observed, “She always climbed that hill.”