Whoever you are: in the evening step out

of your room, where you know everything;

yours is the last house before the far-off:

whoever you are.

With your eyes, which in their weariness

barely free themselves from the worn-out threshold,

you lift very slowly one black tree

and place it against the sky: slender, alone.

And you have made the world. And it is huge

and like a word which grows ripe in silence.

And as your will seizes on its meaning,

tenderly your eyes let it go …

RAINER MARIA RILKE, “Entrance”

The floor plans of the Robert Miller Gallery tacked to her studio wall, Joan was hard at work on her fall show, conceiving of each painting to fit a specific space and aiming for a show that functioned as a whole, which is not to say that she and the staff would not adjust when they saw the canvases in the actual space and light. Among the new works—most bearing elemental titles like Weather, Hours, Days, Wind, and Land—the vast diptych Rain stood out. Simultaneously color and line, its slashing and blurring up-on-the-surface strokes, “motion … made still,” deliver the feeling of a cold, pelting downpour in a way artist Ora Lerman likens to the “visual-kinetic experience of rain on the windshield of a car, when all background information seems obfuscated.” They resonate too with the graphic markings of van Gogh’s 1889 Rain and with the rhythms of skin instruments and marimbas in Gisèle Barreau’s 1988 Little Rain.

Another knockout was the thirteen-foot-wide diptych South. As deliciously sun soaked as Rain is rain slapped, this polychrome homage to Cézanne’s paintings of the Mont Sainte-Victoire (and reprise, in a sense, of Mitchell’s own long-ago La Bufa) knits together often razor-sharp strokes. Her brushes darting around the white canvas, the artist achieves an effect of light so crackling that South appears apt to blaze up at any moment.

Joan’s crowded opening at Robert Miller that October 25th marked her heady reemergence as an important New York artist. Museums took notice. In 1990, her River occupied a prime spot at the Whitney Biennial, the Museum of Modern Art bought Taillade, and, through a purchase/gift, the Metropolitan acquired La Vie en Rose. Her prices soared too. The first Mitchell sold by Robert Miller, a quadriptych, went for over $200,000. That same year, the 1956 King of Spades, estimated at $180,000 to $250,000, commanded $462,000 at Sotheby’s. (This trend continued: in 2004, Christie’s sold her Dégel for nearly $1.5 million; four years later, La Ligne de la Rupture brought over $6 million at Sotheby’s in Paris. Meanwhile, a de Kooning had sold for over $24 million and a Rothko for some $80 million.)

Joan’s reception at Miller was documented by independent filmmaker Marion Cajori, who had approached the artist two years earlier about doing her cinematic portrait and had met with a lukewarm yet fond “Oh, let’s give the poor girl something to do.” The daughter of Joan’s old Tenth Street pals Abstract Expressionists Charles Cajori and Anne Child (later Weber), Cajori had first known Joan as a nine-year-old living in Paris with her mother and stepfather, painter Hugo Weber, intimates of Joan and Jean-Paul. From the beginning, Joan had touched a chord in young Marion: first by the artist’s intense, autonomous, paint-splattered presence under the skylight of her Frémicourt studio in that “classic Parisian light, strong but sad,” later by her ability to maintain, in the expat artists’ crazy, volatile world, a stern loyalty to her work, later still by the way she had “rescued” Marion with her understanding of adolescent angst.

The filmmaker then sought funding, having to clarify, over and over, that, no, her project had nothing to do with singer Joni Mitchell. After she was turned down by the National Endowment for the Arts and the “American Masters” series on PBS, among others, she got angry, having come to see her problems in securing underwriting as analogous to Mitchell’s in achieving recognition of her work: why architect Philip Johnson and painters Jasper Johns and Robert Motherwell on PBS, and not (except for the perennial Georgia O’Keeffe) female-artist monstres sacrés? Eventually Cajori and filmmaker Christian Blackwood set up the Art Kaleidoscope Foundation. Twice they requested that Joan donate a painting to help finance the project, and twice they met with her adamant refusal to underwrite her own film. In the end, however, Bob Miller purchased South and that money was used as the bulk of the funding for the hourlong documentary that brought to La Tour the camera crew who roiled Joan’s life by “traipsing around [for two months] asking rude questions.” Intertwining interviews, lyrical city and landscape shots, and stills of Joan’s work (accompanied by the music of Charlie Parker, Betsy Jolas, Billie Holiday, and others), Cajori’s film reveals a flinty survivor, an artist whose achievement is wed to her rich inner life, a cantankerous grande dame whose tacky-cutesy red teddy bear sweatshirt (a gift from a friend) in one long scene signals her refusal to concede anything to the rules of self-image making.

Scene Two that October evening—never captured on film but impressed in the minds of many—took place at the post-reception dinner in the vast chandeliered and painting-filled dining room of Bob and Betsy Miller’s East End Avenue apartment. There Joan started in verbally brutalizing her tablemate Robert Storr, a friend, painter, and important curator who, shortly thereafter, joined MoMA’s Department of Painting and Sculpture: Storr was “power-hungry,” Joan snarled, and had a “Nazi haircut” besides. In contrast, she had all evening woundingly ignored her old pal Joe LeSueur, who, over the years, had steadfastly loved her and championed her as a great artist. A large Mitchell (a gift from Joan) took place of honor in Joe’s little Second Avenue apartment, wall-to-wall with work by Goldberg, Bluhm, Katz, Hartigan, and others. But at another recent dinner party Joan had blasted Joe for selling one of his Mitchells: “This motherfucker sold my painting for a quarter of a million bucks and didn’t even ask me!”

Her attention then pivoted, that evening at the Millers’, to New York Times art critic Michael Brenson, who, the previous spring, had interviewed her at length in Vétheuil and found her “really lovely to be with, open and charming.” Brenson had been preparing a feature story about how Paris shaped the working lives of three American artists who had swum against the stream by moving to the French capital in the 1950s. Joan framed her experience in terms of otherness, gender, landscape, light, and dogs: Paris, she observed, was female while New York was male; Paris bridges resembled dachshunds, New York bridges, Great Danes. Besides Mitchell, Brenson’s article (published that June) spotlighted her old friends, painters Shirley Jaffe and Biala. Brenson had seen Joan again only the day before her opening, when he walked into the gallery to review her show and found her in Bob Miller’s office, and the three had cordially chatted.

Now, seated across from the critic at a table of eight, the artist, without warning, erupted: “Michael Brenson, you motherfucker! You ghettoized me. You put me with those women.” “The words ‘those women,’ ” Brenson reports, “dripped with disgust.” A hush fell over the table. The critic remained mute. Joan ranted on. Curator Klaus Kertess, seated nearby, remembers her verbally clubbing Brenson for calling her a “woman artist,” something he never did. Joan shortly turned to Klaus: “Maybe I’ve gone too far.” Later, after the tables had broken up, she approached Brenson, who stood examining a painting, hugged him, and made a moist-eyed plea for indulgence: “I only attacked you because I love you so much.” Yet no sooner had she coaxed him to sit down with her for a talk than her tone shifted again, to coldly aggressive. Shrugging off the episode as typically Mitchell, Brenson rose and walked out.

Scene Three: The evening having worn on and the crowd dwindling to fifteen or sixteen, Joan drew up close to Jill Weinberg and began reminiscing about Xavier Fourcade and voicing their mutual sadness over his loss. She “started pushing,” Jill recalls. “She found this little bruised spot. She just kept pushing until I dissolved in tears.” Suddenly everybody was staring at Jill, assuming that Joan was being mean again: “I didn’t think of her as being mean … It was part of the way she was feeling, about the evening, about the dinner, about who was there and who was not.”

“This joint is very vast and lonely and empty empty,” Joan lamented in that year’s Christmas card to Joanne and Phil Von Blon. Once again she had plunged into Rilke, along with Gerard Manley Hopkins and the metaphysical poets, especially John Donne. (Aware that winter’s gloom depressed Joan, Mme. Rousseaux had whet her appetite for Donne by giving her his “A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy’s Day Being the Shortest Day.”) Musa Mayer’s Night Studio, a memoir of growing up as the daughter of painter Philip Guston, and V. S. Naipaul’s autobiographical novel The Enigma of Arrival held Joan equally rapt. A melancholy pastorale, Naipaul’s book hangs upon the consciousness in flux of a Trinidadian novelist who has retreated to the English countryside. This writer’s uneasy unbelonging and trod-under past filter through the landscape itself—fields, forests, roads, houses, farms—described with precision in changing light, seasons, and weather. Joan adored the novel’s marvelous time-warping repetition, as in Monteverdi or a fugue. Little happens in The Enigma: for its self-exiled (like Joan) main character “to live and to write are the same thing,” she observed, “they are both ways of getting through a certain period of time. Naipaul writes about the fact of living and lives the fact of writing.” Neither did Joan separate living and painting: “I take the train to Paris,” she told Yves Michaud, “and I see through the window the landscape or the sky or people … I am always looking at something—with very bad eyes—but that’s what I do. I look and I transcribe all that I see.” Indeed, painting was her “means of feeling ‘living.’ ”

The richly evocative Champs (Fields) paintings, undertaken that winter and spring, exemplify the indistinguishability, for Joan, of living, feeling, and working. The harvest of her many treks to and from the city, into which she no doubt patched sense-memories from the Midwest and elsewhere, they resemble, in feeling and form, tender lyric poems about tilled earth and weather, metaphor for something unsayable. Champs opened at Fournier that early summer with Joan presiding over the vernissage wielding a cane in lieu of a scepter and surrounding herself with a retinue “as if [the gallery],” thought photographer Jacqueline Hyde, “were the court of Louis XIV.”

Seven weeks earlier, she had had a second hip replacement, the success of which allowed her to substitute that cane for her walker and made it easier to paint. Yet, despite the several pillows she was constantly pounding and rearranging, Joan could never find a comfortable sleeping position, and her arthritis (though temporarily relieved by the shots she received in her hands, matter-of-factly, as if servicing a car) was getting worse. Moreover, she suffered from osteonecrosis, the deterioration of her dead jawbone. As a result, she had dramatic gum loss, and her teeth were getting loose. In addition, her jaw had become painfully infected, so she was on penicillin, which she disliked because it gave her diarrhea. Worst of all, sharp abdominal pains sent her to the hospital for three days of tests. She was diagnosed with early-stage esophageal cancer, a type of cancer difficult to treat. She told very few people and simply continued living, unblinkered about the future and determined to experience the present in all its fullness. She did not intend to subjugate her painting to lots of medical procedures or health precautions. (Out of sheer fatigue, however, she modified her hours: she now worked in the afternoon, finishing around seven, and turning in at midnight.) “Keep it going, Ada, every syllable is a second gained,” Samuel Beckett had written in Embers. More than ever, painting sustained her.

She had returned to two of her favorite motifs, memories based in sunflowers and trees. In the new sunflower paintings, crumpled wads of blossoms ride a foaming ocean, tumble through the sky, run riot with bright-shade colors: reds/greens, blues/oranges, reds/blues, lavenders/oranges. Twisting crimson into aqua or throwing a pinkish white veil over a scribble of teal and black, Joan now found in the sunflower singular, saltatory sport. No less variegated, her tree paintings bring to mind rows of poplars or severely pruned plane trees, standing upright and as if backlit with blazing sun, their negative and positive spaces trading places here and there. One cannot help but read these upright forms as metaphors too for human beings, looming and vaguely frightening. When it came time to title this group, Joan phoned Jean to ask, What is the French word for a row of trees along a path or carriage drive on an estate? The word is “mail,” but, in the end, mindful of her own battered condition, she chose “moignons,” meaning stumps in the sense of the bulbous extremities of severed branches or of amputees. This subtlety did not, however, survive the transatlantic crossing: in the United States they were rebaptized Trees.

Joan’s summer of 1990 got off to a heartbreaking start. Long vexed with hip dysplasia, the very ailment that plagued the artist, her frail German shepherds, Marion and Madeleine, had to be put down. While her friend Elga Heinzen buried the two in the garden, Joan got very, very drunk in her room. Insisting that animals beat humans, she loved to pepper visitors with stories about her dogs, and she hated the Catholic Church, in part because, she alleged, it forbids dogs and cats in heaven. Yet she had no intention of getting new pets, matter-of-factly pointing out that she would die before they did. So, for the first time in twenty-two years, La Tour was oddly devoid of dogs and dog noises, except the yipping of Fudji, Gisèle’s crazy little poodle.

As June slipped into July, Joan took advantage of the glorious weather, idling away long mornings on the terrace over her café au lait, her books, and her crossword puzzles. With Gisèle in Florida and Frédérique and Philippe moving elsewhere (though he would continue as her studio assistant), she was living primarily with young American painter Kate Van Houten, who had come out from Paris for July and August, and, off and on, Christopher Campbell (who would also spend the summers of 1991 and 1992 at La Tour).

A PhD candidate in art history at Brown University and a Fulbright scholar, Campbell had been doing research in Paris for a dissertation on Cézanne and Pissarro and painting on weekends. When he met Joan at a party, he had received the inevitable invitation to lunch, “but don’t come if you don’t bring your paintings.” At Vétheuil the next day, Joan informed Christopher that his work was “a complete pile of shit” yet he had talent, so she would be willing to “larn” him painting. Having refused invitations to teach at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Rhode Island School of Design, and École des Beaux-Arts, among others, she nonetheless wanted to test herself as a teacher, and, from that point on, Christopher came out every weekend.

Taking a cue from her own training and from Cézanne, Joan had him draw lemons that first summer during which she repeatedly accused him of not seeing. After he graduated to abstract painting the following year, she often tore his efforts to shreds, scraping off paint, rotating a canvas-in-progress ninety degrees as she explained its defects, and stressing the idea that, if one could get two or three areas going in a Hofmannesque push-pull, then a painting was beginning to work. She also assigned Anton Ehrenzweig’s The Hidden Order of Art so he could better understand how an unconscious involvement with the gestalt of his work could take him beyond the limits of conscious attention. At one point, he was perplexed about a Neocolor (water-soluble wax crayon) drawing that had something, he couldn’t figure out what, wrong with it:

And Joan developed a habit, when she came into the studio [he worked in the cistern] of looking at this drawing and saying, “I know what’s wrong with that.” After about the fifth time … she pointed out that the colors were too aniline, too raw, too ripe, and she must have picked five or six grays from this set [of Neocolors] and started laying thin bands of gray over certain color masses to consolidate and simplify and tone them down, so that the relationships that were there had a chance to function, so that there wasn’t so much color clattering simultaneously. It was an amazing lesson.

But, as much as art per se, Joan talked about feeling.

Only once did he watch her paint. The two had walked up to the studio to get something one evening after dinner when Joan, glancing at a work-in-progress, suddenly realized what it needed. As Christopher made himself small in a corner, she picked up a brush and dealt with the problem. He was amazed to see her walk, all concentration, the length of that studio, precisely place one mark, then return to the other end and look and look and look. His thoughts flew to Cézanne working at the studio in Les Lauves at the end of his life when “observers just couldn’t believe that anybody could wait so long between brush marks. He would mix up the colors, the brush was loaded, it was poised over the canvas, and then, finally, one mark would get made.” With Mitchell, “never was the appearance of speed, or, to the unschooled, of haste, more at odds with the deliberation and precision with which marks accumulated on the surface. It was a gorgeous thing to see!”

Teaching, painting, working with Mme. Rousseaux, and hosting visitors still left Joan long hours during that rather quiet summer. She took on a second, very different, student: a local woman hired to clean and run errands at La Tour. This single mother struggling to raise a five- and a seven-year-old was, Joan had been horrified to learn, illiterate. So the artist went to great trouble to track down the right books for her and her children and to teach her to read. Their sessions proved agitated, the two driving each other to exhaustion. Yet Joan maintained with table-thumping assertiveness that the principle was inviolate: You and the children have to be educated! It’s the only hope for them! Only if you have knowledge can you defend yourself in the world!

That summer too, Joan attended a concert at the Château de La Roche Guyon, not far from Vétheuil, after which she approached the violinist and almost timidly introduced herself. Jean Mouillère took in this spiky, bulging-eyed sexagenarian so obviously moved by the music: “But I know you, you’ve been our closest neighbor on the Chérence road [the back entrance to La Tour] for twenty years.” Over that period, Jean and his wife Christine had observed that when they came home late, no matter what the hour, a light shone and a Bach cantata, or something of the sort, sounded from the studio. “What!” Joan shot back. “And you never stopped by!” But the Mouillères had been less than eager to encounter Joan’s dogs, besides which their owner had a solid reputation for unpleasantness. Joan handed Jean her telephone number, and, the very next day, they saw each other again. From then on, the twosome or threesome frequently lunched or dined together, Joan taking the precaution, when invited, of toting two bottles of wine, usually her favorite Pouilly-Fumé, La Doucette. When she was impossible, she would phone the next morning: “Allô, Coco, I was mad yesterday.” One evening over drinks, she inquired of Jean, “How do you do it? Your sound vibrations go all the way to my belly. It’s strange.” He explained his conception of sound—that the bow is magic and that it effects a geometry involving invisible but constructed lines in space—a conception which so enchanted Joan that she made him come over and spell out the whole thing to Christopher Campbell and, for once, she painted all night.

In 1990, Carnegie Hall in New York commissioned prints from seven eminent artists—Georg Baselitz, Alex Katz, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers, Ed Ruscha, and Joan Mitchell—to be sold to raise funds during its upcoming centennial year. Concerned about the quality of the printing she could obtain locally, Joan hesitated to accept. Then Fournier introduced her to fine art printer and publisher Franck Bordas, whose atelier, in an old-fashioned cobblestoned courtyard off the place de la Bastille, belonged to the contemporary art world yet kept a finger on the métier’s past. The grandson of Fernand Mourlot, famed lithographer to Matisse, Braque, Picasso, Miró, and Giacometti, Bordas worked with an immense, twenty-ton vintage flatbed press (among others) once used for the lithographic posters of Toulouse-Lautrec. After meeting Franck and touring his studio, Joan accepted the invitation with alacrity.

She and Bordas got off to a shaky start, however. Everything he and his team did was dégueulasse! Lousy! Horrible! They had to start over again and again. Operating by provocation, Joan pushed them and herself—everything she did was dégueulasse too—beyond their normal capabilities. The atelier’s walls were soon plastered with working proofs. All the while, Joan was taking the measure of her collaborators, testing them, teasing them, dwelling upon their “little acts of cowardice, little acts of demagogy.” In truth, she took pleasure in the camaraderie and visually rich studio environment, and, as time went on, they worked in scrappy good humor, laughed, and had fun.

Part of the fierce counterattack Joan was waging against the loss of her powers, the Carnegie Hall project meant commuting to Paris four days a week. On Wednesdays and Thursdays, her regular cabdriver, Jean-Jacques Géry, picked her up around ten thirty and took her to the Bastille; later he would meet the 5:10 from Paris in Mantes-la-Jolie and drive her home. (Often she would nod off to sleep in the cab, then rouse herself and invite him in for a glass of wine.) On Tuesdays and Fridays, Jean-Jacques dropped her instead at Mme. Rousseaux’s for what were now twice-a-week double sessions. In either case her day typically included lunch at the old rococo-kitsch brasserie at the place de la Bastille, Les Grandes Marches, where she commanded a regular table with a standing order of two bottles of chilled white wine continually replaced. Creating a congenial, even festive, atmosphere, she would typically convene three or four guests. Not only friends landed at Joan’s table but also strangers, who approached her, Bordas observed, “as a sort of living legend, who came to see her as one comes to see an historic monument.” She took them in stride, unleashing torrents of questions, inviting those she liked to see her again, and picking up their tabs too, meanwhile consuming vast quantities of wine but eating virtually nothing. Afterward she might detour to a nearby chocolatier and return to the atelier with truffles for all.

One day after lunch she nearly stumbled over a man napping on a piece of cardboard spread in the sun outside Bordas’s door: “Who’s that bum?” The “bum” turned out to be Richard Bellamy, the manager of the Hansa Gallery (an East Twelfth Street artists’ cooperative) in the 1950s, and now a private dealer. Bellamy was waiting for sculptor Mark di Suvero, who was also making prints at Bordas. A joyous shout went up, and Dick and Joan fell into each other’s arms. They hadn’t seen each other for thirty years. In contrast, a certain French painter who taught at the Beaux-Arts once came by to have a word with the artist as she worked in the back. One minute the two were chatting. The next, their voices were rising and she was beating him, hard, with her cane—thwack! thwack! He fled. A low, demonic cackle rolled out of the depths of the atelier.

As agitated as Joan was, Bordas perceived her ability to go to a place of stillness at the core of her being, given that

a sort of peacefulness came over her as soon as she started working, a kind of silence. I felt in her manner of working something like a soloist beginning a piece by mentally emptying herself. There was something oriental in her touch, in her work. In contradiction with all the violence, the activity, the provocation. There was a grace and a physicality in her gesture, which meant that, at a certain moment, this fragile woman, fairly old, not very stable, who did not walk very well—one often wanted to give her one’s arm to help her across the street—would lift her brush or her crayon and become a force of nature.

When she finished, she might chirp, “Not bad, huh, for a woman?”

Brilliantly layered, Joan’s eight-colored Carnegie Hall poster, “a kind of miracle of ink” (in an edition of only sixty-four), proved spectacularly beautiful.

Having fun at Bordas, Joan wanted to continue even though she had little patience for complex printmaking processes. Her real interest lay in doing beautiful drawings. Thus Franck improvised a setup that allowed her to draw vertically and found unconventional methods and materials, like fast-drying inks, that agreed with her way of working: “Ah!” Joan would breathe. “That’s better, that’s better, that’s good! I’m beginning to understand.”

Meanwhile, word having gotten out that Joan Mitchell was doing prints at the Atelier Bordas, various dealers and editors popped up, eager to seize the opportunity for what they assumed would be lithographic versions of her paintings. On the basis of handshake agreements, two or three of them ordered editions, which meant that costs could be covered, Bordas could be paid, and Joan could keep going. What these would-be purveyors of Mitchell lithographs did not know was that the artist had further short-circuited the process by limiting her colors to three at most—black, gray, and red—in violent and handsome prints that were almost pure gesture. When Bordas finally offered them previews, he heard but wisely did not pass along to the artist, That’s not exactly what we want, get her to add a little more color. He then turned to Fournier, who cared deeply about Joan’s happiness: Let her work, do what she wants, the latter responded. We’ll take care of things afterward.

In the end, only writer Michel Waldberg of the Éditions de la Différence, who was working on a Mitchell monograph, came through. (The son of sculptor Isabelle Waldberg and writer Patrick Waldberg, whose friendship with Riopelle dated back to the late 1940s, Michel too had known Joan as a youth.) For the others, everything boiled down to money. Joan would continue at the Atelier Bordas almost until she died, albeit less regularly as time went on. Only weeks before the end, she came in to sign her work but tired midway and put the rest aside for later. She was never able to return. Acting with his usual integrity and elegance, Fournier compensated Bordas for everything, including the unsigned and therefore unsaleable prints.

. . .

Joan’s second show at Robert Miller opened on March 26, 1991. The gallery was mobbed, but she was most thrilled by the presence, at both the reception and the huge party Carl Plansky threw afterward, of the great alto saxophonist and composer Ornette Coleman, whom she had first met at the Five Spot in 1959. Speaking to one of the Termini brothers (the bar’s owners) that long-ago year when the Coleman quartet’s ten-week gig and maverick album, The Shape of Jazz to Come, were rattling the jazz world, Joan had declared the then highly controversial musician (and fellow synesthete?) to be “a genius.” In fact, Coleman’s eclectic free jazz—weirdly pitched, beautifully dissonant, open-ended in its phrasing, electric, abrupt, layered, and soulful—is analogous to Mitchell’s painting, his uncanny timbre not unlike her uncanny color, exemplified by her ability to (as painter Brice Marden once pointed out) “make yellow heavy.” Over the years, Joan and Ornette had run into each other here and then, always with pleasure, Ornette feeling a deep kinship with this “just precious” painter—“totally devoted to her creativity” and “free as a bird.”

Three days after the opening, a limo picked Joan up at the Westbury and took her to Mount Kisco, where Tyler Graphics was now located and where, living in the artist’s apartment above the studio, she devoted the next several weeks to lithographs based on sunflower and tree feelings, including several from the twenty plates she had drawn earlier, many only recently proofed. In the late morning, Joan would clump down the stairs and into the studio, freshly showered and almost giddy from having watched Bob Ross’s The Joy of Painting, in which the TV artist demonstrates how to create landscapes with “happy little trees” and “pretty little mountains.” A long, intense day would follow, yet at midnight Joan would still be going strong. One time she got so drunk that she had to be carried upstairs, then insisted everyone stay for a nightcap. At three a.m. she was typically “yakety-yakety-yak,” recalls Tyler. “The conversation was so good, you didn’t want to go to sleep, and it got to the point where you couldn’t keep up with her. She was too sharp, and you were too foggy. And she’d get grumpy because you weren’t playing the same alert game that she was. So she’d start attacking you.”

Among Joan’s visitors at Tyler that early spring was Nathan Kernan, John Cheim’s assistant at the Miller Gallery, who had gotten to know her the previous July when he traveled to France with Bob Miller and spent a night at Vétheuil. On that occasion he had made a point of telling Joan he was a friend of poet James Schuyler, whereupon she had quoted Jimmy: “And when I thought, / ‘Our love might end’ / the sun / went right on shining.” Later that evening it came out that Nathan too wrote poetry, and Joan demanded examples. No sooner had he returned to New York than she was on the phone, pestering him about sending those poems. He mailed off a few, expecting the worst. But Joan liked them, and, from then on, broadcast what he would have kept private: that he was a poet.

Nathan’s visit to Mount Kisco that April came two days after Schuyler’s death following a stroke. Joan had clipped the writer’s obituary from the Times. Sad (though she hadn’t seen Jimmy for years) and solicitous of Nathan’s feelings, she peered out the kitchen window of her apartment during their lunch, lifted her eyes to the perfect April-blue sky, and quoted Verlaine: “Le ciel est, par-dessus le toit / Si bleu, si calme!” (“The sky, above the roof, / is so blue and still!”)

Back in New York in the days that followed, she asked Nathan to escort her to Schuyler’s funeral. He came by the Westbury around six that day, and together they took a cab through the light spring rain to the Church of the Incarnation on Madison at Thirty-fifth. The ranks of Joan’s old friends were thinning: Elaine de Kooning had died, Pierre Matisse had died, Sam Beckett had died. Publicly stoic, she sat at the back of the church during Jimmy’s service, after which she ran into and reconciled with Joe LeSueur.

With other old friends, she had terrible fights. Around this time, Zuka—whose friendship with Joan had survived the vicissitudes of half a century—got to know an American journalist, a delightful woman, albeit a bit of a snob about her Mount Holyoke and family connections. One evening, Joan, Zuka, and Zuka’s new friend all attended a dinner party in Paris at which Joan had arrived drunk and determined to get the woman for putting on airs. She gleefully proceeded to do so, until finally Zuka blew up: “Will you stop picking on my friend!” With that, Joan trained her guns on Zuka, and the party fell into a shambles. A few days later, both attended a reception at the Orsay Museum where Joan walked up to Zuka and opened with a quick salvo: “You know, the other day, you were absolutely wrong! I mean, she was aggressive with me before I became aggressive with her.” Uncharacteristically, Zuka exploded, then turned heel and strode off, and, for weeks, the two did not communicate. Finally Zuka wrote to suggest they patch things up two minutes at a time. Over the years, Joan had often called her more levelheaded friend in a “truly unhappy, desperate” state and Zuka had prodded her into two minutes of thinking about something else, then two minutes more, and so on, until Joan shed her angst. Zuka now ended her note, “If you think our friendship’s worth saving. You decide. I think it is.” Joan phoned, but it was never the same after that.

Carl Plansky next felt the lash. Five years earlier, Carl had turned his penchant for paint making into a business, Williamsburg Art Supply, from which Joan now purchased her oils. When a certain blue she had used in quite a few canvases began cracking and falling off, Joan’s vituperation knew no bounds. It was aimed at both Carl and (in case the primed canvas was the real culprit) the Montparnasse art store, Adam. A letter of apology from someone at Adam only added fuel to the fire: “as if his letter would make up for the time I lost because of that idiot!” One expert who was consulted reported that the problem was surely Joan’s brushes. How often did she wash them? In fact, her brushes, kept in dog food cans on her studio floor, had not been washed in a decade.

Besides the brushes, these cans, one for each color, held turpentine (occasionally topped off), on which floated assorted dead bugs, plus about two inches of pigment that had settled to the bottom. When she wanted to use a particular color, Joan would dash the can with fresh turp and stir it up. “In a sense,” Christopher Campbell had realized,

she got enormous physical complexity out of that situation … because you take a brush that’s already supercharged with pigment and dripping with turpentine and you charge it with all this fabulous fresh paint and you move it in a big gesture on the canvas and you’ve got this hypercolored saturated turpentine flying around, you’ve got the mass of new paint, you’ve got the old paint, you’ve got an extremely complicated physics of surface going on.

The result was sometimes an overdiluted layer of paint that did not form a continuous film and thus, when dry, broke apart.

Joan promptly put Christopher to work washing 380 brushes but did not own up to her own role in the blue fiasco or apologize to Carl: “It’s a horrible thing to say …,” Carl begins—but how to find the words?—“this fabulous art, and anger, anger,” Joan’s rare, freaky, and chilling rage.

That same episode caused a deep rift in her already tumultuous friendship with Yves Michaud. The artist had given the critic a painting called Yves, but when the blue cracked he returned it, a sure way to enrage Joan, who would have destroyed Yves had Fournier not stepped in. A painting, after all, was a gift of self.

It mattered not at all that Michaud was an art world luminary. Joan never hesitated to quarrel with an important critic, offend an important collector, pick a fight with an important curator, or slam an important journalist. When cultural critic Deborah Solomon interviewed her that summer for the New York Times Magazine (during a four-day stay at La Tour, where Joan had invited her on the condition that she wasn’t “some Ivy League type who refuses to do dishes”), the artist, feeling that Solomon didn’t “get it,” worked herself into a terrible state. “My painting has nothing to do with what’s in and what’s not,” she snapped to Solomon at one point. “I do it. I’m not hurting anyone. I’m not selling Palmolive soap. I’m not asking you to look at my art, and I’m not asking you to buy it. So leave me alone. Let me die in peace. I’m not a story.” But she was: Solomon’s “In Monet’s Light”—again, the Monet connection—appeared that Thanksgiving weekend.

Lunching at the Dôme one day around the same time with John Cheim, Whitney Museum curators Klaus Kertess and Richard Marshall, and the Whitney’s director, David Ross, and having gotten out of Ross the story of his health problems, Joan abruptly went after him for supposedly feeling sorry for himself. She blustered on and on. Disgusted with the tirade, Ross stood up to leave, but Joan reached over, yanked him back into his chair, and ordered him to “SIT DOWN!” She hadn’t finished yet.

No doubt Joan’s physical and mental anguish contributed to her churlishness. It also prompted her to begin settling her moral debts. She purchased (as a loan) a house for Gisèle in Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, near the National Conservatory of Music, and apparently worked out a way for her cook and gardener, Raymonde and Jean Perthuis, to stay in the Monet cottage for the rest of their lives. For Phyllis Hailey, who had died so tragically thirteen years earlier, she painted a tree.

In format, color, and composition, the gloriously wheeling L’Arbre de Phyllis (A Tree for Phyllis) echoes a certain oil on paper, one of the best of many the young artist had done of her favorite ginkgo tree across the road from La Tour. Joan’s calligraphy perfectly captures the ginkgo’s ruffled foliage; her shimmering, light-intoxicated yellow conjures its feeling in late October. Simultaneously a means of atonement, parting lesson, and ultimate sanctuary for the young painter, L’Arbre de Phyllis once again merges a tree with a person for whom Joan cared deeply, thus embodying her visceral sense of love breaking all boundaries as well as her almost pagan belief that (as she told one visitor), “Phyllis is still painting in these hills.”

An unbeliever, Joan had no faith in an afterlife, except that she was always imagining the surroundings of loved ones who had died and always painting havens for their spirits. She felt she had to give them a place. Part of Joan’s unspeakable terror of death, after all, had to do with equating the ending of life with blankness. “Blankness to me is absolutely no space, no silence, no sound, no …,” she once explained to a friend, segueing from a comment about how she slept with a security sound. “The word blank is what bothers me. It has no image to it. B L A N K. It’s nothing … That’s sort of frightening when one goes blank … It’s scary.”

How did Joan, then, with her consuming fear, come to grips with the gathering darkness? Leading as she did a very considered life, including four hours a week set aside expressly for interior work, she attempted to prepare for death yet found her “morbidity” undented. Burning with fine fury at human mortality—“Do we ‘rage rage’ [‘against the dying of the light’] as Dylan did or quit??”—she strove to die well by continuing to live life to the fullest. She hated the idea of losing self-control as much as that of wasting time on self-pity and felt that the trick was to care deeply about something outside yourself. Poetry and music helped: Rilke, of course (“Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. / Just keep going. No feeling is final”), and the timelessly beautiful Four Last Songs of Richard Strauss, which culminate in serene surrender to the inevitability of death. Joan saw friends, followed tennis and figure skating on TV, fretted over the state of the world, and painted. She may have felt able to salvage from her illness even more intensity than before for her work; on the other hand, she sometimes moped around La Tour, questioning the worth of what she had created: “I feel time is very short, and I’ve done nothing.”

In recent years, tensions had sporadically run high between Gisèle, on one hand, and Frédérique and Philippe on the other, thus aggravating Joan’s off-again, on-again feelings of entombment in her big house. La Tour was looking rather shabby: cobwebs trailed from the ceiling, the furniture was battered, the walls needed a fresh coat of paint, stuff had accumulated everywhere. The village too—“la France profonde,” as she exaggeratingly called it—depressed Joan, especially in autumn and winter, so rainy, silent, and dull. She considered her living in France to be an accident. With the dogs dead, she had no reason not to move and, at one point, decided to share a place in New York with Valerie Septembre, a painting conservator whose family came from Vétheuil. But then inertia set in. Not just inertia—Joan knew that her New York had vanished.

In 1989, Jean Fournier had bled off some of her discontent, however, by renting and fixing up for her a haven in Montparnasse that Joan dubbed her “secret studio” and where she felt free, now that the dogs were gone, to work and spend the night. Situated in a charming old studio building at 23, rue Campagne-Première, a short street where artist Man Ray, photographer Eugène Atget, writers Louis Aragon and Elsa Triolet, and Rilke himself had once lived and where Godard filmed the ending of Breathless, Joan’s place was high ceilinged, light flooded, and appealingly empty. Among the few friends whom she told of its existence were Mme. Rousseaux, whose new office was only a ten-minute walk, and Michaële-Andréa Schatt, with whom Joan shopped for items she would need in town, all the while expanding upon her dire need for this sanctum for deep rest and intense work, pastels only. Its mezzanine held a bed, a few books, a radio, nothing more. (Serendipitously, one of her neighbors played the piano, rather well, and Joan loved the occasional burst of faint music.) In the main room downstairs stood several canvas chairs, the wooden panels to which she tacked sheets of paper, and the rolling tables on which she arranged her pastels, some jumbo sausage sized, others worn down to nuggets. She used two types, both soft, Sennelier’s standard grade and pastels made by a certain little old lady since time immemorial. Laid out in small boxes, they glowed with the éclat of jewels.

As months went on, Joan let more and more people in on the secret. After she told Klaus Kertess, he offered her a pastel show at the Whitney, thus sparking a marathon of drawing, which she did back in her studio in Vétheuil. Wanting to smash all lingering notions of pastel making as a genteel, ladylike pastime, Joan made hundreds of vigorous and sure-handed drawings. Overlaid here and there with plummeting tendrils and gossamer veils, their velvety knots of color, all sensuous after-rain freshness, bristle with sheering spikes and snaggy or sinuous curves. Working on three drawings at a time, Joan devoted herself to this project for several months until finally, one day that fall, she phoned Klaus: “Get your ass over here; I’m tired of the pastel dust on my studio floor. It makes me feel like I’m a ‘Lady Artist.’ ” He promptly arrived, along with John Cheim, to select work for the show, some forty pastels, all untitled, for the museum’s Lobby Gallery.

At her opening five months later, the artist, in leather jeans and a turtleneck, greeted visitors surrounded by her “bodyguards” from the Whitney staff. A woman a few years younger than she introduced herself: Sally Turton, the granddaughter of her father’s beloved sister Gertrude. Sally and Joan had not set eyes upon each other for decades, but, having read about Joan’s upcoming exhibition, Sally had tried to round up as many family members as possible to attend the reception. Other than her daughter, however, not a single one was willing or able. The two had flown out from Chicago. As they chatted, Joan revealed to Sally that she had cancer, adding, “You know who my father was. My father was a cancer specialist. [He wasn’t.] But he isn’t around to save me. If my father were here, I wouldn’t have to die.” Fundamentally, Sally thought, cousin Joan hadn’t changed a bit: the same hard-edged personality, seemingly indestructible because of her force of character, but also the same fragile little girl longing to be saved by her father. In fact, Joan had recently titled a painting Gentian Violet, again (privately, since no one else would get it) fastening upon Jimmie. As the three Mitchell women used to joke, he had treated every scrape and scratch with the antiseptic gentian violet.

Yet Joan knew she was beyond saving. She had made these hundreds of drawings using neither a face mask nor adequate ventilation to protect herself from the fine pastel dust, which is filled, as she was fully aware, with carcinogens and other toxins hazardous to the lungs. She had fatalistically followed the needs of her work, even when it took her into clouds of noxious color.

The summer of 1992 passed. Christopher Campbell again lived at La Tour. Joan painted prodigiously. She continued her psychoanalysis and, though crushingly tired, saw many people. Sometimes she would call her friend, lawyer and writer Guy Bloch-Champfort, and say, “I’m alone, please come,” and he would arrive to find her surrounded by people. Wanting in the worst way for her long-ago lover Evans Herman to fly to France and play for her, she pleadingly tried to arrange it through their mutual friend Marilyn Stark, but, for reasons now unclear, it never happened.

All the while, she was feeling intense pain between her ribs but said little about it. Once Gisèle spotted a fleck of blood at the corner of her mouth. Her teeth wobbled, her jaw tormented her. Yet she may have stopped taking the penicillin prescribed for her chronic infection because its side effects annoyed her. Extremely thin, she looked and felt every bit her age. (During the Whitney show, leaving the Westbury with Robert Harms one day, she had paused, stared in the mirror, moved her hair around a bit, and lamented, “God, Harms, it isn’t easy, getting old.” She was sixty-seven.)

One night Joan had a vivid and deeply troubling dream in which her jaw was missing. That dream occurred as she was preparing to travel to New York, on October 12, to work once again at Tyler Graphics and see the Matisse retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. She went directly from the airport to Mount Kisco.

Among Joan’s projects-in-progress at Tyler were the Trees, Weeds, and Fields series of prints and the artist’s book Poems. Having decided several months earlier that she wanted to do an artist’s book, she had asked Nathan Kernan to suggest a poet with whom she could collaborate. He had. But, the next thing he knew, it was understood that the two of them were doing a book together, an idea that made him uncomfortable because he felt Joan should work with someone of her own stature. He tried to talk her out of it until finally she said, “Don’t worry, let’s just make something and have fun.” She was, of course, forcing the issue of his being a poet. Now that project awaited final decisions. The result would be dazzling: eight Mitchell lithographs “illuminating” eight Kernan poems, loosely connected by the theme of loss, in a handsome paper folio made of Mitchell’s recycled lithographic proofs.

But, ensconced in the artist’s apartment at Tyler, Joan uncharacteristically lollygagged in bed, coughing blood from time to time. After three days, Marabeth Cohen-Tyler, Ken’s wife, insisted upon taking her to their family physician. Dr. Rummo diagnosed very advanced lung cancer.

Abruptly, the end was upon her. Although she had long expected the worst, Joan was unaware that her cancer had metastasized to her lungs and, like everyone else, was shocked by its severity. Yet she took the news as well as one could, phoning Gisèle: “It’s all over. I’ve got lung cancer.” For Fournier, whom she reached at the opening of the Paris FIAC (International Fair for Contemporary Art), she mustered a touch of humor: “Jean, I’m in really bad shape. I’m returning to Paris. FIACs don’t agree with me.” (Her cancer of the jaw had been diagnosed on opening day of the FIAC in 1984.)

The very next morning, Joan, in a wheelchair, Ken, Marabeth, Marion Cajori, John Cheim, and Klaus Kertess all met at the Museum of Modern Art to view the mammoth Matisse retrospective. As they rode up in the elevator, Joan broke the hushed silence with a warmly affectionate “Matisse! That motherfuck!” Yet the exhibition itself almost failed to stir her. “You know,” she confessed to John, “I really know all these already. As much as I love [this painting], I’m not that interested at this moment. Because I’ve adored it all, and I know it all.” Still, she could not pass up the opportunity to nettle Ken, as he wheeled her through the galleries: “He knew how to use blue, Ken! You could learn a lot, Ken. Look at that blue!” Afterward Joan wanted to see the Ellsworth Kelly drawing show at Matthew Marks. Then came lunch at Robert Miller Gallery. Miller was showing the work of seventy-five-year-old Abstract Expressionist Milton Resnick, who also lunched at the gallery that day. Seated next to Milton, Joan started in teasing her old friend, and bursts of laughter kept erupting from their corner of the table. Lunch was followed by visits to the Max Beckmann show at Gagosian, Claes Oldenburg at Pace, contemporary sculpture at Marlborough, Katherine Bowling at Blum Helman, and Ellsworth Kelly prints at Susan Sheehan. Joan beamed.

She seemed in high spirits the next evening too, at a dinner party thrown by Ken and Marabeth for Joan and fifteen friends at Cricket Farm, the original Tyler workshop in Bedford. Though dependent upon friends for material and emotional support, she felt able to give by sharing her deep respect for life and keen enjoyment of aliveness, even at this alarming juncture. Driving that week with the Tylers past fields, horses, and woods in their full October glory, she had never stopped observing, admiring, and pointing out this splendid light, that fabulous color.

Joan’s flight had been booked for the following Wednesday, only nine days after her arrival. In the studio, they were still midstream with several etchings, Joan herself “really cooking” with the work. Of course, everyone tiptoed around the fact that she was dying, and there was lots of talk of the future: Ken was going to bring the plates to Vétheuil, and so on. Finally, the artist spoke out: “Let’s cut all the bullshit, okay?” she told Ken. “You’ve got to straighten up and understand a few things about what we’re going to do here.”

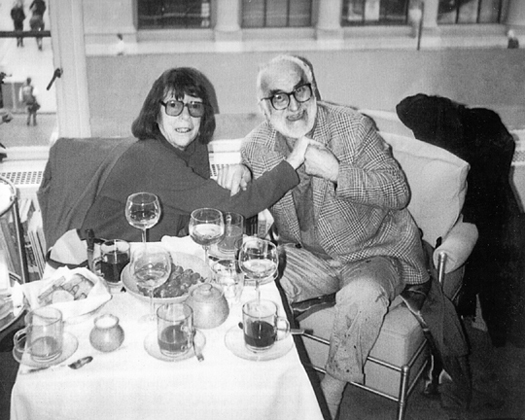

Joan and painter Milton Resnick laugh it up over lunch at the Robert Miller Gallery, a few days after she learned she had advanced lung cancer, 1992. (Illustration credit 16.1)

“Yeah! You’re going to finish everything that’s up in the press room as fast as you can. I don’t have a lot of time. And, second, you’re going to promise me that whatever we start out selling these prints for, that’s it. You’re never going to raise the prices. I don’t want these things to go the way the blue-chip guys are going.” The normal practice in publishing print editions is to keep increasing the prices, but Joan wanted hers to remain at a level that would not deter young people from buying.

Joan spent her final New York days in Manhattan, seeing friends and completing a panicky rewrite, one of many over the years, of her will. Among its wiser stipulations was the establishment of the Joan Mitchell Foundation, with the mission of demonstrating the vital necessity of painting and sculpture and of helping artists, chiefly through grants and educational programs. Tuesday evening was devoted to a small dinner party at John Cheim’s Twentieth Street apartment with Hal Fondren, Robert Harms, and art writers Lisa Liebmann and Brooks Adams. The following morning, as Ken and Marabeth drove her to Kennedy, tears abundantly flowed: Joan was “a wreck when she got on the plane,” Ken remembers. “We were wrecks when she left.”

Joan lived her final days with courage and grace. Flying on the Concorde, she arrived at Roissy around ten thirty that evening. When Gisèle and their driver, Jean-Jacques, met her, she was unable to swallow. Yet when they got to La Tour, she invited Jean-Jacques to come in as usual for a glass of wine. He knew she was quite ill, nothing more. That night Gisèle’s poodle, Fudji, jumped from his mistress’s bed and, to Joan’s delight, came to sleep with her. One can imagine her feelings the next morning at leaving Vétheuil and arriving at the Curie Institute, which she always found profoundly depressing.

There, Prof. Brugère, whom she called “my gardener” because of the instruments he used, did tests and confirmed that her cancer had spread to the trachea and lungs. It was extremely advanced. She asked for a date. Brugère said fifteen to twenty-one days. There was a high risk of hemorrhage and immediate death.

Eventually Joan was put in a single room, small and banal, with a horizontal window that silhouetted people against the light. Alerted by Gisèle, friends quickly appeared, some refusing to believe that Joan was dying. Among them was Monique Frydman, to whom Joan said good-bye (as it turned out, since Monique had to leave town for several days) with the words “Neither man nor woman. Neither young nor old.” She meant painting. “Take care of yourself.”

John Cheim, who had crossed the Atlantic close on Joan’s heels, also took for granted that she would recover. Though barely able to speak, she remained playful and tough and, when the light showed through her hospital gown, he noticed how beautiful her legs were, like a girl’s. Nearly everyone smuggled in white wine. When Zuka arrived, she was amazed to find Joan seated in a chair in the hall amid a coterie of young French painters, sipping Chablis and looking “like a queen holding court.” In intense pain and unable even to walk to the toilet, she drank with her friends as long as she could get a glass to her lips.

By Sunday morning she was in terrible pain. Joe Strick and Guy Bloch-Champfort alerted a doctor, who gave her an injection. Hooked up to an IV and heavily sedated, she mostly kept her eyes closed, yet, for a time, stared at the deep blue delphinium someone had placed on the windowsill. Gisèle marveled that Joan remained capable of wonder. She continued to draw upon some primal energy until finally she slipped into a coma. When Christiane Rousseaux visited on Tuesday morning, she found Joan comatose yet showing a glimmer of recognition in her eyes. At her bedside nearly day and night, the devoted Gisèle read her mail to her when it was just the two of them, though surely Joan was beyond comprehension.

On Thursday, a deathwatch began. Gisèle, Frédérique, Philippe, Guy, Hervé Chandès, and Sally Apfelbaum (who couldn’t help but think that she represented Joan’s ties to her own country) stayed into the night and took turns holding Joan’s hands: strong and stubby working hands, Sally realized. She was cradling them that Friday morning, October 30, at 12:50 a.m. when Joan died.

Franck Bordas heard the news from a weeping and devastated Jean Fournier. For Joan’s dealer, the artist’s final weeks resonated with those of early-eighteenth-century French Rococo painter Antoine Watteau, who, near the end of his short life, had returned to Paris from London, his lungs nearly destroyed by consumption. Watteau’s gallerist and friend, Edme Gersaint, cared for the testy, restive, and dying artist, who insisted upon painting a sign for Gersaint’s shop “to loosen up his stiff fingers.” So ill he could work only in the mornings, Watteau painted in seven days, “no, five days” (as Fournier told this parable of sorts), his enormous oil on canvas, expending much of his remaining life force in the effort. Watteau’s painting depicts, as if from the street, minus its façade, the interior of an ideal gallery bustling with activity. A painting about beauty and transience, Watteau’s masterwork also attends to the vital role of gallerist as intermediary between artist and art lover and illuminates, in the words of art historian Donald Posner, “the sense and worth of art and the artist’s life.”

In the months following Joan’s death, Fournier advanced preparations for her simultaneous shows at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes (spanning the period 1951 to 1982) and the Jeu de Paume in Paris (beginning with the Grande Vallée suite). This French retrospective had been in the works since 1990, but only shortly before Joan left for New York had its curators, Alfred Pacquement, then director of the Jeu de Paume, and Henry-Claude Cousseau, his counterpart at the museum in Nantes, along with Fournier, spent a “memorable and moving day” at Vétheuil. Joan had once again resisted the rummaging through the past that a retrospective entails but, at the same time, “violently” (the word is Fournier’s) desired the exhibition at the Jeu de Paume. As Jean was driving her to Mme. Rousseaux’s one day and speaking of the venerable museum, Joan had gripped his hand: “Jean, I would do anything to show there!” Shortly before her death, she had visited the Jeu de Paume to look over the space, and the thought of her paintings in that soft light and on the edge of the Tuileries Gardens had made her supremely happy.

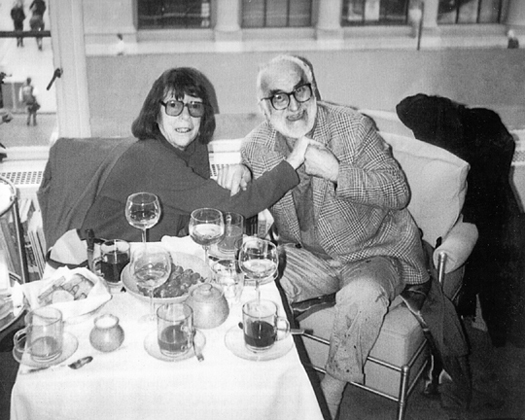

After receiving the prestigious Grand Prix des Arts of the City of Paris from French Minister of Culture and Education Jack Lang (center), 1991 (Illustration credit 16.2)

Joan’s obituary had made the front page of Le Monde, the newspaper of record, and Minister of Culture and Education Jack Lang had issued a statement: “With Joan Mitchell, we lose one of the great women artists of our era.” (“Women artists!”—one can hear Joan’s harrumph.) The previous December she had received the important Grand Prix des Arts de la Ville de Paris. “I—‘Joan Just Girl’ from Chicago—received the French Grand Prix for painting … I couldn’t believe it,” she wrote the Von Blons.

Around the same time, a Mitchell was hung in the official prime minister’s residence, the Hôtel Matignon, where Joan and Jean Fournier lunched with Prime Minister Michel Rocard. A certain French cultural elite appreciated not only her painting, but also her intellectual capabilities, deep knowledge of French culture, excessive personality befitting an artist, even her rather French bent for bristly unpleasantnesses. Her hospitalization at Curie had been an item on French TV news. Yet she was little known to the wider public. Nonetheless, her dual 1994 exhibitions, a popular and critical triumph, drew a record 38,000 visitors to the museum in Nantes and nearly 50,000 to the Jeu de Paume. The latter included her protégée Joyce Pensato, who was taken aback when, as she strolled through one gallery, Cajori’s film played in the basement and that familiar voice faintly lashed out.

At the time of her death, Joan had been painting toward a third Robert Miller exhibition. In her studio one morning that August she had carefully arranged her brushes and visually caressed her paints, reassured by the fact that looking at them made her yearn to paint, which meant she existed. She could no longer unscrew the caps on her paint tubes, so someone did it for her, and could no longer climb a ladder, so she used extra-long brushes.

One of Joan’s last paintings, the consummate Ici (Here), no doubt completed that summer, brings to mind the day she had arranged to meet her neighbor, Jean Mouillère, in his garden, which had been thrown into more chaos than usual by an early spring heat wave. The first poppies and roses were blooming amid the last tulips and irises. Having hobbled into this horticultural jumble, Joan halted, leaned on her cane, and then, her eyes enormous behind her magnifying-glass lenses, let out a stupefied “My God!” before falling intensely silent. Rife with wonder at the raw beauty of the landscape, boisterous with color, movement, and light, Ici is Mitchell’s “My God!” I am alive at this moment in this place!

Completed about the same time, Joan’s approximately nine-by-twelve-foot diptych movingly titled Merci makes its viewers feel small because of the scale of its strokes, the wallop of its colors, and the vastness of its space. Four powerfully painted calligraphic shapes—five including a scribble of near white on white—hang in the void. Joan’s marks are primal, charged, and devoid of convention, cliché, or irony. How anyone frail, arthritic, semi-ambulatory, farsighted, and dying of cancer could make such a swaggeringly bold painting will always be a mystery. Shorthand for Joan’s lifelong adoration of painting, Merci contains the lake, the sunflower, and the tree; the blue and the orange; the white; van Gogh, Cézanne, Matisse, and the Great Abstract Expressionist Mark; fear, fury, aloneness, and love.

Sixty-seven-year-old Joan at her studio in Vétheuil, 1992 (Illustration credit 16.3)

In Joan’s last paintings, all untitled, centered blue or yellow treelike forms, as festive as maypoles, float on white ground. They simultaneously snug the surface and pull away. Here the psyche has very fluid boundaries, dissolving into majestic summer blue or liquid satin-curtain yellow. Trees for herself, as she had painted so many trees for departed friends, they recall Pierre Schneider’s long-ago words: “A Joan Mitchell canvas is the story of Daphne, a being seized by panic, gasping for breath … who at the moment her strength fails escapes by transforming herself into a tree.” And Joan’s: “I become the sunflower, the lake, the tree. I no longer exist.”