4. How to feel the fear

Light, refraction and fear

It’s 2.30 a.m., and my room is filled with thick darkness and ice-cold silence. There is no one here to realize how petrified I am. I want my mum, but she is at our family home, a forty-five-minute drive away. I can’t stop feeling anxious about the colour orange and the texture of biscuits in my head, and the smell of new shampoo on my pillow. I can’t sleep and I want to go home.

Night-time was always a moment of peak anxiety for me. My ADHD induced insomnia, while my ASD filled the waking hours with obsessive thoughts and fears. I would find myself caught in the middle: scared to sleep and afraid to be awake. I would often need my mum to move her pillow into my room and sleep on my floor, so I would feel safe enough to get through the night.

These night terrors were just one example of the fears that have followed me through life. There are the obvious anxiety triggers that still affect me today, like sudden loud noises, or large crowds of people. And then there are fears whose origin even now I struggle to understand. I can sip on a carrot-and-orange juice – my weekly treat – and wonder why this colour used to repulse me so much. Orange food, orange clothes, orange plastic seats, all once seemed like toxic or contagious substances to be avoided at all costs. This is part of how ASD works, creating instinctive and repulsive fears that can’t be explained, but must be obeyed.

Fear is something we all have, and it’s something we need, essential to our survival as a species. Without fear we have no scepticism, no caution, no check and balance on our impulses. But the opposite is also true. When all we can feel is fear, it becomes paralysing, leaving us unable to think clearly or make decisions at all. Your fears might be small ones, about a difficult meeting at work or admitting your feelings to someone. And they might be large: phobias you have always held, worries about major changes in your life, fears about ill health or financial issues. Whatever the case, fear accompanies us all whether we acknowledge it or not, and whatever size the dose. Unless we understand our fears, untangle their root causes and examine those issues rationally, we risk being controlled by the things that make us afraid, rather than taking control of them. Fear can be irrational but more often it’s highly logical and reasonable; and our response to it must be the same.

With Asperger’s, there are moments when all your thoughts and fears rush onto you like a beam of blinding light. You experience everything all at once and have no inherent ability to separate the different emotions, anxieties, impulses and stimuli. Another of my great fears was fire alarms, a terrifying noise that would send my senses running red hot as the noise reverberated through what felt like my entire body. Imagine a feeling of total physical dread. At school, while the other students would neatly form ranks like soldiers, I always had to run as far and fast away from the noise as possible.

At moments like these, I have to live in darkened rooms, with the blinds closed, noise-cancelling headphones on and quite possibly the safe canopy of my desk to sit under. This was, and is, my survival method. But it’s not a way to live. I needed something that allowed me to get ahead of my fears, as well as to hide away from them. Because I have no in-built, unconscious filter, I knew I had to create my own: one that would allow me to cope with fear and function alongside it.

And, just as the feeling of fear felt like a blinding light, my study of photonics (photons being the quantum particles that make up light) helped me to realize that they could be broken apart in the same way a beam of light can be refracted, revealing its many different colours and frequencies. Our fears, which are never as singular or overwhelming as they sometimes feel, can be treated in exactly the same way. With the right filter, we can open up, understand and rationalize our fears – seeing them in a new light. So save your #nofilter for Instagram. In real life, we need all the filters we can get.

Why fear is like light

Shadow and light have always fascinated me. At home I had my favourite tree, in whose shade I would stand to feel safe. I have always needed areas of low light intensity as a protection against sensory overload.

But I also loved light and was enraptured by its properties. On the windowsill of my mum’s bedroom she had placed a crystal oyster shell, which refracted the sunlight all around the room, revealing the natural treasures of the sun as it broke into its full spectrum of colours: piercing red at the top, and serene violet-blue at the bottom. Everything would come alive in that moment, at 7.30 every morning when I rushed to watch it, dreading the winter months when cloud would deprive me of the spectacle.

This was a moment of peace and wonder in a day that might be filled with all kinds of fear and anxiety. I instinctively knew that I needed a prism of my own for the thoughts and feelings that tangled in my head like spaghetti gone wrong. I had to separate my fears, understand everything they contained and unravel a sensation that was otherwise overwhelming.

I started off by reliving the most vivid parts of my day – sitting safely under my desk, naturally – and trying to associate each scenario with its most powerful emotion. What had I been feeling so strongly about and how had that contributed to the situation? As I plotted the map of my emotions, I kept coming back to those mornings watching the light refract through the oyster crystal. My anxiety attacks were like a beam of white sunlight – overpowering, impossible to look at directly, and something you can only turn (or run) away from. But within that sat a whole spectrum of emotions, some stronger and more immediate than others, all interplaying and tangling together to create fear.

Refraction was a perfect lens to help me understand and classify my fears because of my synaesthesia, a condition in which normally unconnected senses become linked to each other. For some people that means you can see sound or taste smells. For me, it has always meant that I feel colours as well as seeing them, and they all have a personality of their own. By seeing fears on the light spectrum, they became clearer to me, as well as more distinct.

You don’t need to have synaesthesia to benefit from this perspective. Nor do you have to be someone who suffers from an abundance of crippling fears. We all have fears, at the front or back of our minds, and we all face moments when fear takes hold of us in ways we struggle to control. Has anyone ever told you in these moments to slow down, or pause for breath? Well, that is exactly what refraction achieves. When light passes from one substance to another, it will change speed. Because light travels less quickly through glass or water than air (both having a higher refractive index), the wave of light will slow down. In the classic prism example, like my mum’s crystal, the light then disperses into its seven visible wavelengths: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet (plus the invisible: infrared and ultraviolet).

In other words, by slowing down the speed of the light wave, we are able to see it differently: in its full glory and many colours. The prism effect gives us a new perspective, turning something that was singular and dazzling into a spectrum that is much clearer, and even more wondrous. If we want to understand our fears properly, we need to do exactly the same thing: look at them through a new lens, so we can see them differently, and change how we respond accordingly. In other words, we need to get on a wavelength with the things that make us afraid.

Getting on a wavelength

Refraction happens because light does not travel in straight lines, but in waves that oscillate and undulate dependent on their energetic differences at any one time. You have waves to transport light through space, and the same applies to sound waves, radio waves, X-rays and microwaves. They are all around us, but light waves are the only ones we can actually see.

Every wave, whether it’s the one that allows a fishing boat to tune its long-wave radio (the only one that can reach it out at sea), or the one you use to cook a ready meal, has its own frequency. A high-frequency wave has tall peaks that occur close together, like a particularly spiky Toblerone bar. Its low-frequency cousin unwinds more gently, similar in form to a loosely coiled snake. The higher the frequency, the more energy is carried, but the less distance it can travel in a prism since it interacts with the atoms contained within, dissipating energy. The higher the frequency of light, the more it will bend upon contact with a medium of higher density than air (such as glass or water). The pace at which waves travel affects everything we see and hear around us: during a storm, you will see lightning flash before you hear thunder rumble, because light travels faster than sound (by about a million times through air, moving unencumbered, while sound interacts with the elements around it). In reality, both occurred at the same time.

When light refracts through a prism, we see the different colours because the higher refractive index of the glass has slowed down the waves to a speed that falls on the visible spectrum (waves that can be seen by the human eye). The refractive index simply quantifies the speed of light relative to the substance: a measure of optical density that tells us light travels more slowly through denser objects (so progressively slower through glass, which is denser than water, which is denser than air).

As the light makes this journey, we are able to see something that was previously invisible: that there are different colours within light, each with its own wavelength. Red is the longest, so travels the furthest, and is bent the least by the prism. Violet is the shortest, and refracts the most. These differing wavelengths explain why a rainbow will always have red at the top, bending around furthest, and violet at the bottom.

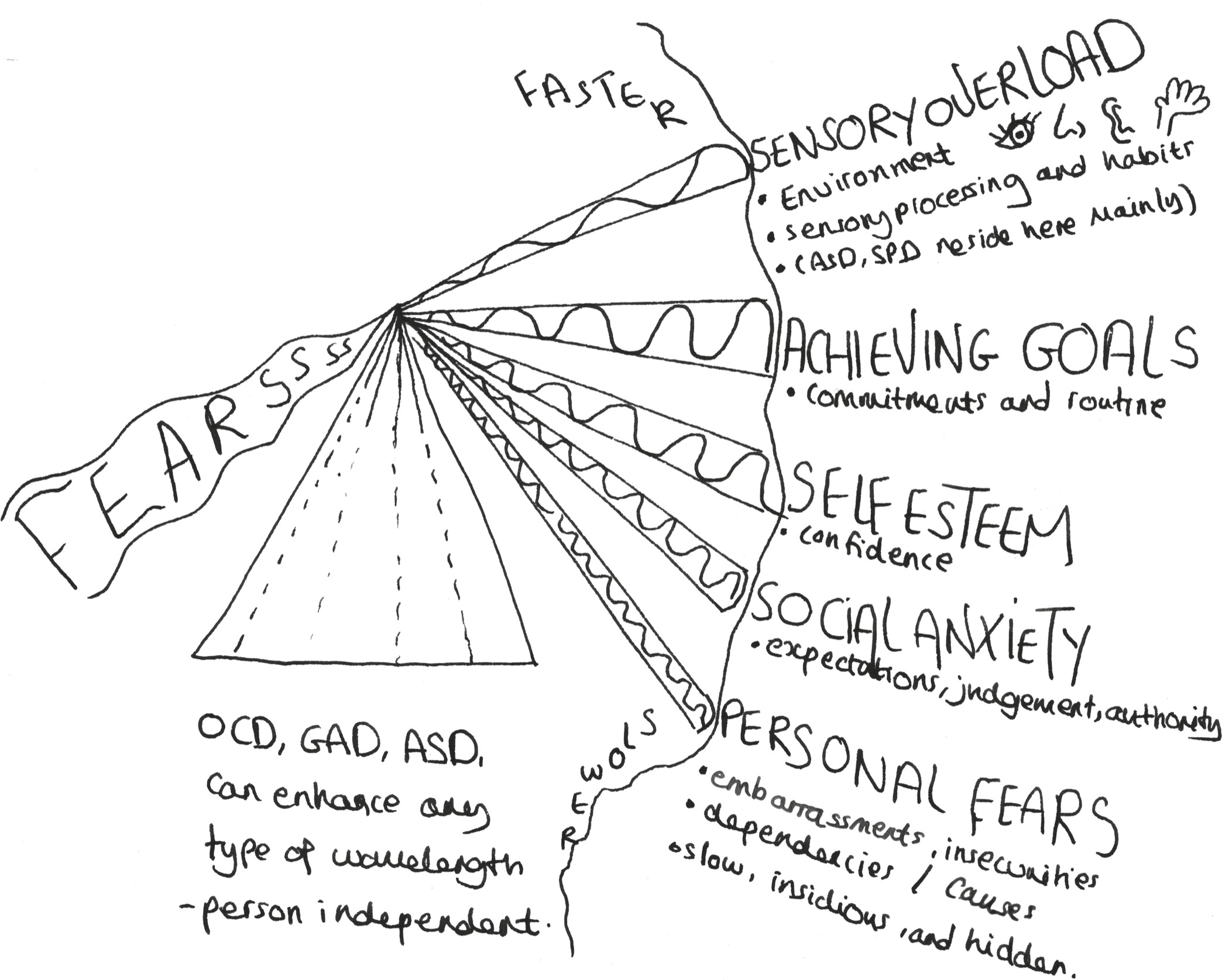

Wavelengths are important to our fear and light analogy for two reasons. Firstly, the initial sense of fear, the blinding white light, is not singular but actually contains many different emotions, triggers and root causes. And secondly, these are not all equal: like the different colours in light, our fears and anxieties have their own wavelengths, with varying intensity. Some will flare vividly over a short distance (which for me could be hearing a loud noise in the street), while others will maintain a less insistent, but more sustained, drumbeat in our heads (such as my fear of having to look people in the eye). The most powerful, insistent emotions are like high-frequency violets – intense and choppy – while the nagging feelings are more laid-back, low-frequency and long-lasting reds. And, just as happens at sea, sometimes different waves combine to create a tsunami of fear that you are powerless to prevent from crashing over you.

This was my biggest breakthrough in managing the fears that threatened to derail me. Anxiety is not a single, solid state resting in our heads, but a fluid entity that contains a multitude of different components. The concept of refraction can help us to separate these, untangling the different things that make us afraid, distinguishing between the high- and low-frequency triggers, and ultimately finding ways to manage them.

When I feel a panic coming on, I use the prism effect to diagnose the situation and try to avoid a full-on meltdown. Is it a high-frequency wave, a sensory trigger in my immediate surroundings, like someone accidentally brushing past me, shouting loudly or giggling at a high pitch? Or is it one of the low-frequency, constant thoughts that occupy me: fears about the future, getting ill, or whether my itchy jumper is going to give me psoriasis?

Am I experiencing an ADHD panic, where I feel nauseous because there isn’t enough to stimulate me, or an ASD one, where there are too many options, my mind goes blank and I have to retreat into my cave? One feels like spinning outwards, a fairground ride that’s going faster and faster; the other like spiralling inwards, detaching from the world and retreating into myself. Unless I understand which it is, and why, there is nothing I can do to prevent the gravity of a meltdown.

While there is no such thing as simply ‘conquering’ fears, it doesn’t half help to understand what you’re dealing with if you’re going to manage them better. We need a prism. In fact, we need to be the prism.

Becoming a prism

With fear, our natural impulse is to try to make it smaller. We think that if we can compress our fears into the smallest possible box, locked away in the furthest recess of our minds, then we will be able to live free from its influence. But hoping that fears can be controlled in this way is akin to supposing the sun may stop rising one day. If something is giving us anxiety, it will continue to do so until we understand why that is, and what we can do about it. Denial is not an option, even if it is our instinctive first recourse.

I have tried this approach, giving up things I enjoyed: taking part in mud runs and extreme sports, buying posh jam at full price (which I do in defiance of a former boyfriend, who would only ever buy on offer), or even – the Holy Grail – falling in love. All are things I want but know will also make me afraid. But denial is worse than fear: a sort of mental constipation that traps you and eventually makes you hate yourself for being so safe. Being opaque in this way is no more sustainable than trying to hold your breath for ever: eventually your spirit will suffocate. It’s better to risk feeling afraid than feel nothing at all – to make yourself transparent enough for the light to shine through.

Going cold turkey on my anxiety triggers didn’t work, so I knew I needed a way to become transparent to them. It meant I had to become the prism – not pushing fear down but opening it up, letting it shine through me and breaking it into its constituent parts so I could study it in detail, better understand its nature and ultimately cope with it.

Fear is an intangible, something that exists in our minds, and so our prism has to be a mental one too. It is about training the mind to filter fear, putting it through a virtual refractive prism, rather than letting the white light of anxiety cloud our ability to think rationally. This isn’t something you can easily or quickly learn. A good way to start is by thinking about previous scenarios and trying to establish retrospectively what made you afraid. Usually there will be several contributing factors, so try to establish each in turn, and think about how they interacted with each other. Try to separate the things that caused the fear from those that simply compounded it. Recall which emotions were the most vivid and all-consuming. Tease apart the different strands until you have a full spectrum of emotions, spanning the high-frequency triggers and the low-frequency anxieties. By doing this, you map your fear, turning it from an intangible feeling of dread into something you can understand, explain and better navigate in future.

Over time, you get better at this until you are able to refract in real time, holding up your mental prism to fears as they happen, and hopefully finding a way through. It’s not a foolproof method, but the more I do it, the better I get at coping with the fears and anxieties that crop up in my everyday life: from being willing to step out of the front door each morning, to navigating my morning commute and managing work and social situations. Instead of being a sponge for fear, soaking it up until I can absorb no more, I try to make myself a prism that can refract a high-intensity beam right through me.

I think about making myself into the densest possible prism, bringing together all my experiences of a particular event or fear together in one place. This gives me the processing power and mental density to reduce the speed the fear is travelling at – just like light through glass – minimizing the chances of being overwhelmed. I’m then back in control, able to study the new threads of colour and detail that have been opened up. This is hard when I get entangled in anxiety, and my head starts to spin like a disco ball in darkness, but it’s only by becoming the denser prism, slowing the fear down, that I am able to cope with letting the light in.

For example, if someone asks me to look them in the eye, I will immediately feel a burst of short-wave, white-light fear. I need to work fast to avoid being overwhelmed by this instinctive, deep-seated fear, one that strikes at the core of my ASD self. Through the prism approach, I can separate out some of the waves within that white light: the longest, reddest one that represents a fundamental fear of human contact from the more immediate, violet wave that is my fear of someone’s eyes burning through my public mask, seeing through the well-practised exterior and revealing my anxious core. Once these threads have been identified, I can start to rationalize with myself: yes, I don’t relish this kind of human contact, but I know from experience that it won’t actually hurt me. And no, this person probably isn’t trying to look me in the eye to reveal anything: they’re just trying to have a conversation. They’re not going to find out simply by looking at me how much I have learned about them just through observation. Only once the different strands of the initial fear have been separated can I bring this kind of logic to bear. It’s neither feasible nor sensible to try to rationalize the fear in its rawest, white-light state. First it has to go through the prism.

Building up this kind of density is also a good opportunity to bring all your thoughts together – allowing you to base decisions on patterns of accumulated data from past experience, not moments of panic or anxiety. By taking this approach we can improve not just our response to fear, but our overall decision-making process: a kind of high-intensity workout for the mind akin to the HIIT sessions that have become popular in the gym.

How, then, can we develop and hone our mental prisms to achieve this? It starts with behaving like one, and learning to be more transparent. Instead of being ashamed of the things that make us afraid, as if they represent weakness, we should be honest and open about them. We shouldn’t be afraid of telling our friends and family about our deepest fears, and we certainly shouldn’t feel embarrassed about sharing them – whether with a personal friend or a professional. Being transparent about the things that make us afraid is a necessary part of developing the prism mindset. It’s what allows us to move on from the urge to compress our fears, and makes us ready to look at them through this new lens. Though it is important to note that this is a two-way process, since to open up you need to feel that it is safe to do so. This can be hard in a pressured environment where you have to perform, such as in professional life which drives us towards the robust, masculine facade of indifference – a very low refractive index if you ask me.

How to be transparent will depend on the individual. Just as different materials all have their own refractive index, the speed at which light can travel through them, we must all develop our own comfort level. Some will find being transparent easier than others. I have always been something of an open book, showing and saying exactly how I feel. This transparency goes both ways. Lacking the realism filter, I might see a motivational poster on the London Underground that reads, ‘Anything can happen to you’, and think it means I am about to contract a deadly disease, or succumb to silent and immediate death. Have you ever thought you might be so open-minded that you overload yourself with anxiety every single day? Welcome, it is a hard life being so transparent that you quite literally scare yourself.

By contrast, you might be someone who is more inclined to hold on to their feelings, and less willing to share their fears, ironically from a fear of human judgement. But transparency, and honesty, are not avoidable if we want to get a handle on fear. Unless you learn to think and behave like a prism, you are going to struggle to mimic its wonderful ability to turn that anxiety beam into the beautiful, understandable and manageable wavelengths that created it. Being more open is the first step to managing our fears, and is the route to feeling alive again. And if that makes you afraid, then fantastic. You know exactly where to start.

Turning fear into inspiration

Having tussled with fear and anxiety throughout my life, I eventually came to an important realization. Instead of being one of my greatest liabilities, anxiety is actually one of my most important strengths. It allows me to accelerate possible outcomes in my head, reaching conclusions much more quickly (out of necessity, because there is so much data to process). The methods I’ve described in this chapter are an important part of how I turn the downward spiral of an anxiety attack into potential epiphanies – maximizing my processing power and capacity to bring together the different threads of my experiences and ideas.

These techniques allow me to function without being overwhelmed by fear, but that’s not all. I also find something inspirational about looking into the white light of my fears. It’s the same impulse that has always drawn humanity towards fire – a source of huge danger that also powered human evolution – and which explains why children will always try to look directly at the sun, even (perhaps especially) when they’ve been told it’s dangerous.

Mental ‘refraction’ is a coping mechanism but also a catalyst. It disperses the blinding light of fear into something amazing: the colours of the rainbow. In the same way, the things that make us afraid also contain the ideas and the stimulus to inspire us. Our fears are full of rich thoughts that, when separated out in a way we can cope with, allow us to see ourselves and the world differently. To engage with the things that challenge us and make us afraid is also to come closer to the ones that make us feel alive – and which give us ideas about what to try next.

The denial approach to fear isn’t just a bad way to feel less afraid. It also makes you miss out on things. If I had never faced up to my fear of looking people in the eye, I would have lost much of the human connection I value most of all, precisely because I find it hard to establish. I might not like the process of meeting someone’s gaze, but I know that the end result will often be worth it.

By trying not to be afraid, you also limit your capacity to be creative, inspired and amazed by new or unexpected things. You stop learning, improving and evolving as a person. Fear is a part of us, and if we try to shut it down, we close off some part of ourselves as well. The better I have got at coping with my fears, the more I have realized how important they are – and how much I would regret their absence.

Fear is a funny thing because, although I may have given the impression that it surrounds every aspect of my life (and that is to some extent true), in other ways I am comparatively fearless. For instance, telling people what I think has never been a problem for me, including those whom others may fear as authority figures. Human judgement just doesn’t do it for me, since fearing your own kind doesn’t make any sense.

Imagine the response when, at the age of ten, I told the headmaster at my school to ‘Mind your own business and stop reading my mail’, after a letter I was writing to my parents in class had been confiscated. ‘That letter wasn’t meant for you, but for my parents. You shouldn’t have opened it as it is none of your business.’ That earned me a reprimand lasting several hours, but I wasn’t afraid of the headmaster, his out-of-proportion ears or the callused, caveman-like finger that immediately directed me to his office. I believed that I was justified, and I didn’t fear him simply for being in a position of authority. The filter that makes many people wary of authority figures simply doesn’t exist in my head – they have to earn it through actions and behaviour over time.

When it comes to fear, we all have our own particular anxieties. I’m not afraid of the things that you probably are, but I can be terrified by things you wouldn’t even notice, often deemed ‘silly’ or ‘unnecessary’ (which always makes it worse). Lacking the typical filters, I’m both overexposed to mundane things, and unaware of the many social conventions and norms that I haven’t carefully taught myself through experience. I can be simultaneously overwhelmed thanks to my ASD, and then bored stiff courtesy of ADHD. I might get completely thrown off by a change of routine in a gym class, but very calm if I learn a family member or friend has cancer (which makes me a bad exercise partner, but an excellent listener and therapist). When you actually have to live with #nofilter, it can be a disorientating experience, but it’s also a true representation of the strengths of neurodiversity, and the contrasting skills it allows us to bring to the table.

Whether you are someone with few filters or many, there is one I believe we all need regardless, and that is the prism perspective on fear. We need the dispersal effect of the prism to turn fear from something overwhelming into a force we can control, and ultimately embrace. It’s important to think about being in control of fear, rather than simply banishing it from our lives. Fear is something we need, and which can be part of how we inspire and motivate ourselves. When we are afraid, we are also reminded of what is valuable in our lives, and of our human instinct to protect the people and things we love.

If we try to lock fear away in mental boxes, then we lose all the advantages and keep all of the costs. By contrast, embracing our fears and putting them through the mental prism helps us to turn fear into an asset we can manage, like harnessing electricity from tidal waves. I know there will never be a day of my life when I don’t feel afraid. But I also know that it’s thanks to fear that I really feel alive. Fear isn’t something we need to ‘shine a light on’. It is the light, one we can all learn better how to live with, and even benefit from. It’s why I see the fear that my ASD instils in me not as a problem to solve, but as a blinding privilege to take advantage of.