6. How not to follow the crowd

Molecular dynamics, conformity and individuality

I have always been fascinated by how things and people move. Aged five, I would sit watching the dust particles float across the sunlight that beamed through my bedroom window. I was mesmerized by their abundance and how the particles moved in phases, most together while a few always seemed to go astray. I would sit in the morning sunlight, eyes closed, feeling the warmth on my face and counting how many particles I could feel landing on my cheeks. In fact, I was only allowed to do this for fifteen minutes a day, because I enjoyed it so much that I would otherwise have happily sat there all day, basking in the dusty sunlight.

The movement enraptured me, and so did the sense of magnitude: that we as humans could be so ultimately insignificant in number to other things we could hardly see or understand. At this point in my life, before I had learned any biochemistry, the smallest thing I understood was one I had just been taught in school: the full stop. This was my proxy for what I would later come to know as the atom. Understanding these would surely hold the secret to the clouds of dust that I bathed myself in every morning.

As I sat daydreaming, my mum’s voice floated up the stairs. ‘Millie! I’m not going to ask you again, what do you want on your toast?’ Having swaggered downstairs in my fake glasses (I still held a candle for Elton John at this point), I blurted out the much more important question on my mind. ‘Mum, how many full stops are there in the world?’ Her eyebrows furrowed in laughter. ‘That’s a yes to Vegemite then, I take it?’

I never got a satisfactory answer about the full stops, but ever since then I have been someone who observes and analyses how the world around me moves. I would sit in a café, pretending to read a book, but actually watching how people move around and behave: on their own paths and relative to each other. What was predictable and what was random? How much could I rely on the dynamic behaviour of others when it came to finding my own anxiety-ridden path through the crowd?

I watched and I read: Thomas Hobbes on the nature of man, Adolphe Quetelet on l’homme moyen (an average person whose behaviour would represent the mean of the population as a whole). I played Civilization V, as a way of simulating how different human decisions mapped out on a grand scale. And, every time I got on the train or sat in the playground at school, I observed and learned more about how people behave relative to each other, and the patterns of human movement.

The question I was trying to answer was a fundamental one. Is our behaviour essentially individual or conformist? Do we move according to our own rhythm, or to the drumbeat of the crowd? Are we one of the particles of dust that make up the cloud, or one of the outliers? Unlike Hobbes – although I think I could definitely work the ruff collar – my motivation wasn’t philosophical. For me, this was a deeply practical question. Unless I could project with some degree of certainty how the people around me were likely to behave, I would never feel safe among them (or indeed anywhere near them). Before I could summon the courage to attempt a journey through the scary, smelly crowds of people who pack every shop, pavement and train platform, I had to understand their norms. I needed to study them so I could look after and reassure myself. Otherwise it would be back to where so many childhood outings ended up, hiding in our car being comforted by my sister, a coat over my head to block out the noise and light.

It was Lydia who first made me think about the crowds that scared me in terms of a game. Turning a busy street into a kind of human Tetris would allow me to make light of the situation, and put my scientist’s hat (and coat) on. I could turn something that made me afraid into one I actually enjoyed: a theoretical problem to be studied.

All of which has meant that, although crowds still rank among my greatest fears, watching people is one of the great pleasures of my life. I can get more entertainment tracking the vagaries of pedestrians crossing the road than I can from a whole series on Netflix. It’s my equivalent of cavemen sitting around the fire, watching it burn. Call me boring, but there is nothing tedious about human behaviour, even in the most mundane situations. In fact, like the classical elements of earth, wind, water and fire that so fascinated ancient scientists, there is unpredictability and intrigue at every turn. These everyday narratives might seem slow, but when you start to look at all the branching stories happening right around you, there is enough to sate the appetite of even the most impatient person. Much more dramatic than a scripted TV show or film – which strings its narrative across a predictable arrow of time – can ever hope to be.

I believe that everyone can benefit from what I’ve learned through this process, even if walking down the street is something you can do without having to think twice (in my case twenty times). The conflict of individual and collective applies to us all on some level. When it comes to setting the course of our lives, we all face decisions about the things we want versus what society expects of us, or compels us to do. Almost every major decision we make has both personal and communal motivations, and sometimes they pull us in opposing directions. Balancing individual needs and collective demands can be one of our greatest challenges.

We need to understand the context of our lives, and the behaviour of the people and environment around us, if we are to plot an individual course with confidence. Are our behaviours normal, and do they need to be? Can you be an outlier without becoming ostracized from the common pool? Does it matter if we want and need different things from the people around us? To learn about ourselves, we have to look outwards and study the movement of the crowd through both space and time.

Crowds and consensus

Is a crowd defined by the behaviour of the collective, or by the many individuals who are a part of it? Or for my purposes, as I sought to plot a path that would avoid unnecessary interaction, should I be looking at the individual people or the pattern of collective movement as my guide?

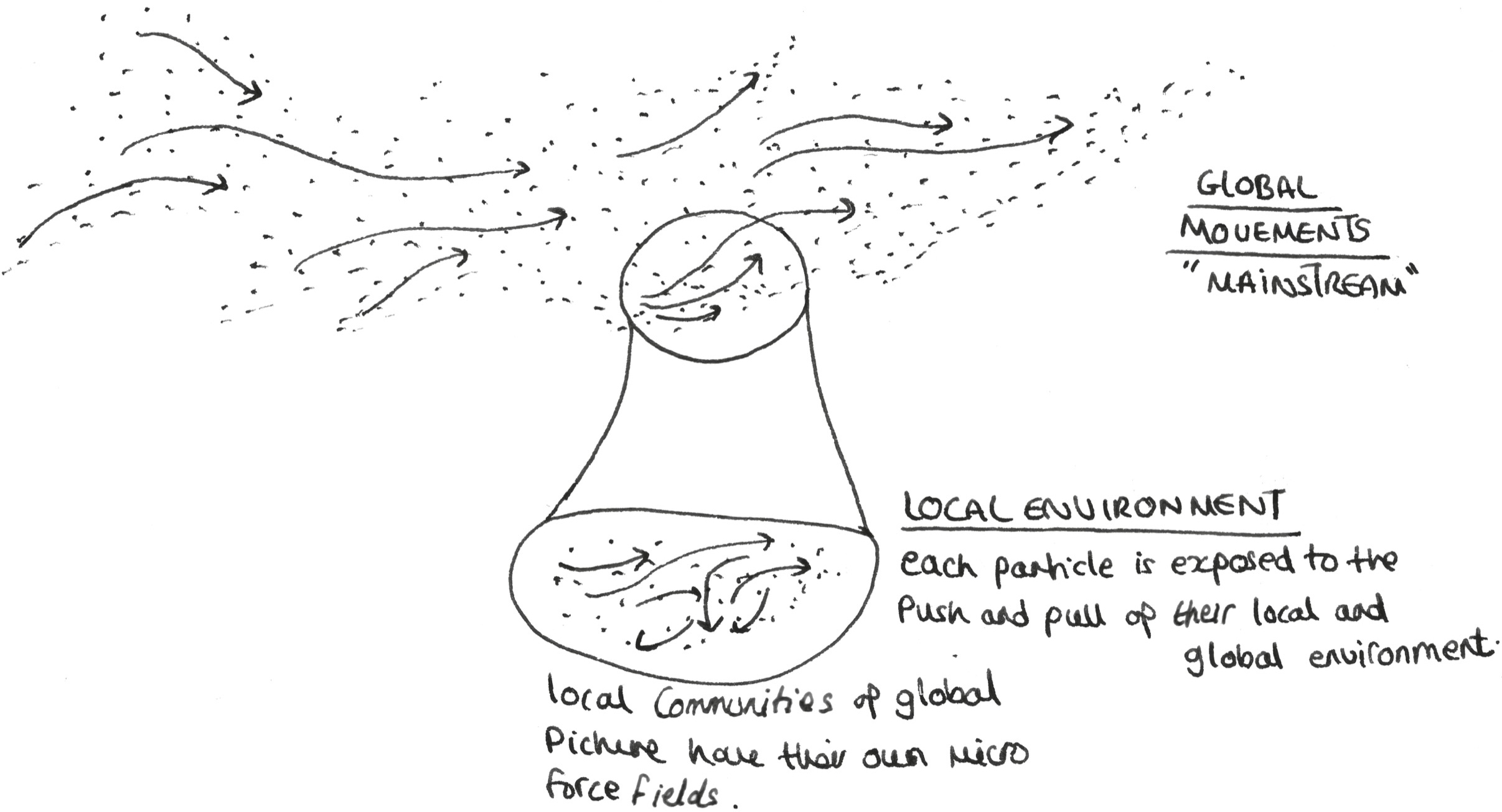

My inclination was to start from the bottom, with movement at the molecular level that I had read about in my chemistry books. Perhaps this could be scaled to a human level, modelling a predicted trajectory for each individual person, just as I would track a molecule moving through a force field. This led me to observe how people moved differently, some stepping aside out of politeness or kindness, others being more assertive and adamant about their right of way, rushing because they were busy or wanted to look as though they were. There were fast people and slow ones; bulky ones and smaller, more agile bodies. A diverse mix: like the atoms that have created them in all their forms.

What I quickly discovered is that trying to account for the movement of every single individual is simply not possible. This is what I instinctively want to do on every commute, but it leaves me exhausted and in dire need of a cat nap. Like trying to count dust particles, you will soon find that you run out of time, patience or energy.

Trying to measure things at the individual level isn’t just impractical. It’s also unhelpful scientifically because people, like particles, don’t act entirely independently. We are part of a system, a wider environment of tangible and intangible components – from other people to inanimate objects, the climate and social conventions. We participate in the system, and we are also in many ways shaped by it. Consciously or otherwise, we observe and absorb the behaviour of the people around us. It conditions our assumptions and indirectly helps determine our actions. A flock of birds can change direction in a matter of seconds, because of how thousands respond to and anticipate the movements of just a handful. At different speeds, the same happens to us as we assess which way the person walking towards us on a pavement is going to go, or how people are likely to react to a major life decision.

The existence of the system gives us something else to measure: something more feasible. And while you might assume that analysing a system can’t tell us much about the behaviour of its components, kinetic and particle theory would disagree with you. Because while an individual might display apparently random and unpredictable behaviour, systems as a whole are more reliable actors and more valuable witnesses. They have been my starting point to understanding how to manage my own motion relative to everyone else’s.

The key concept here is Brownian motion, the theory that explains how particles move around. It shows that particles suspended in a fluid (which can be liquid or gas) move around randomly as they collide with the other molecules within it. This is the molecules we can’t see (without a microscope) pushing around the ones we can, through sheer force of numbers – the pace and direction of the movement determined by the unique factors of the local environment. Brownian motion shows us that, while it’s important to focus on the big picture, we have to look at smaller-scale events to understand both how and why change happens. This is true whether you are looking at a decision in your own life, the movement of a crowd or the evolution of an economy. What is happening at the smallest conceivable level, when aggregated together, makes a big difference to the overall landscape.

The theory – which played an important part in establishing the existence of what we now know as atoms and molecules – was inspired by the Scottish scientist Robert Brown, who wanted to explain how pollen could move across the surface of an apparently still lake. Its chronology dates back to the Roman philosopher Lucretius, who wrote about how dust particles move through light, two millennia before the same sight captivated five-year-old me.

But although the essence of Brownian motion is about unpredictable movement – the progress of each particle is even known as a random walk – that’s not the whole story. Microscopically, every particle is doing its own sweet thing, buffeted this way and that by the liquid or gas molecules that surround it. But change your perspective to the macroscopic – the big picture – and you see something quite different. Through this zoomed-out lens, randomness starts to give way to a pattern. The collisions between molecules are unpredictable, but their overall effect is the opposite. Via Brownian motion, the particles in question will disperse about evenly across the surrounding fluid. This can be seen through diffusion, by which particles move from high-concentration to low-concentration areas, until they are evenly distributed (the reason you can smell baking right through your house, even though it is only actually happening in the oven).

Like the pollen or the dust, as individuals we follow an unpredictable path – one conditioned by how we interact with our surrounding environment. But when all those paths are modelled and viewed together (thanks to a handy technique known as multidimensional scaling), the direction of travel becomes clear, allowing us to see what is going on overall.

This realization allowed me to take a formulaic approach to navigating myself around busy city centres and streets. Using Newton’s second law – force = mass × acceleration – I could predict the likely path of traffic as long as I knew the relative proportions of the different elements – people – and perhaps some context about the time of day and where most of them were heading. So the town centre on a Saturday, with lots of heavier atoms headed towards a rugby match, was very different from how it was during the school run, which had its own molecular peculiarities. Each distinct environment was created by the different molecules involved, their movement and interactions: something that can be studied in the same way as molecular dynamics, the science of how molecules move through a force field over time.

For every place I would regularly visit, and at the times I was likely to be there, I used Newton’s law to help me determine a formula for how people would move. In fact, this was one of the reasons I have always wanted to make myself physically small, so my own mass has as little effect as possible on the overall experiment (the observer effect, in which you seek to minimize the human error or influence of observation on the natural behaviour of your sample).

By understanding and modelling consensus behaviours I gradually managed to counteract some of the innate fear I felt in the presence of crowds, with a sense of certainty about how they would behave. My anxiety started to give way to waves of euphoria, releasing me from the chains of the attacks that would previously hit every time I stepped outside. Now I had a compass and a map to navigate a situation that once routinely sent me into meltdown. Brownian motion had convinced me that there was enough certainty to make it safe. I could plot my own path.

Crowds and individuality

If studying crowds taught me something about conformity, even more important was what I learned about individuality. Although modelling systems can demonstrate the existence of consensus behaviours, it by no means follows that we as humans are homogeneous. In fact, one of the most irrational human beliefs is that there is such a thing as the rational or normal way to do anything. When you have ASD, you quickly realize that people invoking the ‘normal’ is usually a thin veil for fear or prejudice.

Looking at the crowd through another lens shows that, just as there are patterns to be identified across individual behaviour, there is a significant level of variance within the consensus.

This is where ergodic theory, a mathematical idea used to study dynamic systems over a period of time, can help us out. It holds that any statistically significant sample of a given system will display average properties of the whole, since any of these microstates is theoretically as probable as any other to be occurring elsewhere. A different state, somewhere else in the system, is no more or less likely than the one you are currently observing. In other words, my ‘normal’ is just as likely to be indicative as yours within a stochastic (randomly occurring) process of a suitable scale, observed for a sufficient amount of time. Take the dust clouds that once used to fascinate me. Any individual particle is actually an indicative microcosm of the whole system, displaying average behaviour in both its conformity and randomness. It’s no more or less normal for a particle to be an outlier than part of the main grouping over the entire lifetime of the system. Its range of movements will always be representative of the whole, as long as you track its behaviour fully across space and time. In the same way, every person who has ever been treated as an outsider has in some ways been typical: representative of a community that they may never even have met. It’s the smallness of our individual and social worlds that conceals this: persuading us we are seeing the entire system when in reality we only ever glimpse a tiny subset, drawing misleading conclusions as a result about average behaviour and ‘normality’.

Within ergodic theory there are multiple branches of study that explore which systems do and don’t fulfil the criteria. But the essential point is the important one to grasp: any large enough sample of people on a Tube carriage, crossing the road or putting down towels on the beach will ultimately be indicative of the average behaviour of other people within the same system at another point in time.

Consider that and then think about the individuals who make up your sample. There will be people of all shapes and sizes, races and genders, neurotypical and neurodivergent, with and without mental and physical health conditions. This slice of average contains all of us – in all our weird and wonderful diversity. You might call me crazy (plenty have) but I am as much a part of the indicative sample as you are. The whole system, moving in its consensus direction, contains all number of variances between individuals. Our differences remain strong and defining, even as we are essentially trying to do the same thing, and squeezing our divergent behaviours into an overall mean.

As a demonstration of human behaviour, the crowd is doubly ironic. From a distance, we see a homogeneous bloc and tend to overlook the individuality that facilitates the whole. While up close, within the heat and noise of the crowd itself, we see only the individuals, and lose sight of the collective movement they create. The assumptions we make as a result can easily end up backwards – seeing difference as a problem rather than a contributor, and assuming that consensus behaviour should trump individuality, when in fact it depends upon it.

Learning about ergodicity helped me to see that the human obsession with stereotypes is one of our more harmful traits. We rush to categorize people into distinct boxes to which we assign particular assumptions and expectations, often negative. And we then use those artificial categories to demonize people, emphasizing difference as a social and cultural weapon. Ergodic theory reminds us that there is a category, and we’re all in it: the human race. It’s within that capacious box that our similarities and differences should be considered – respecting the delicate balance of consensus and individuality which is the essence of being human. Any attempts to do otherwise are as disrespectful to the science as they are to people.

It is so easy to draw the wrong lessons, ones which enhance division and discrimination, and so important that we spread the right ones: an understanding that it is the sum of our individualities that makes us whole, and that an overall consensus depends on people breaking the rules as well as following them. We need people who deviate from the mean to explore ideas and places no one else has gone to. A mainstream will wither without its outliers to refresh, challenge and extend the overall consensus. Everyone has a part to play (even hipsters).

Embracing diversity in this way is something that has been essential to human survival through centuries of evolution. The same is true in our bodies, where cancer cells rely on their mutational outliers to accelerate progress: it’s the side branches – subclones – that make cancer so hard to treat, because they allow it to adapt to different scenarios and respond dynamically to attacks. Cancer’s diversity of structure is what gives it options – and the same is ultimately true of humanity. We rely on the outliers to evolve and avoid the stasis of the bystander effect, where everyone simply copies each other and no one goes to help the person in need.

Ergodicity is something that has been hugely important to me. As someone who grew up feeling like an island, it took me a long time to even glimpse the other coastlines, let alone build bridges to them. I have had to model the dynamics of the crowds in my life from the ground up – blind to the social nuances and ‘isms’ that instinctively inform most people’s chosen paths. But when physics and probability showed me that even I – with all my weirdness – had to be part of the overall system, it allowed me to see myself in a different light. I know I am connected to the whole, part of the world’s most powerful and beautiful system, the one that allows us to fulfil our evolutionary purpose as a species: to stay alive.

That has enabled me, as someone who isn’t wired to connect with other people, to develop bonds of empathy with my friends and family. Because now I understand that all my extreme experiences – struggles with mental health, a sense of isolation and difference, prejudice from my peers – aren’t a barrier between me and other people, but catalysts that allow me to connect better: a wormhole between different galaxies of living, mine and theirs. My empathy for people in difficult situations is an order of magnitude greater because of everything I have gone through, and the advice I can offer as a result. I know I have lived in all these situations, and that connects me to the people in my life who are having difficulty. I can quite literally envisage myself in their situation. Ask anyone who is neurodivergent or lives with a mental health condition: endless endurance and innate adaptability are our hallmarks. ASD and ADHD are my qualifications every bit as much as PhD.

Empathy has to be a balancing act, because if we give too much, we risk sacrificing our own endeavours on the altar of others’ needs. Some people want to make you feel selfish when you are only trying to protect your own time and priorities. I might want to build a bridge from my island, but that doesn’t mean I can cope with everyone crossing it whenever they feel like it. That said, since I started to experience empathy, it has become almost like a drug for me – something I didn’t have access to for so long, and now pounce on at every opportunity, like someone who spent years without seeing light or tasting food. For years I yearned for human connection, to show that I am made from love, and that those like me – who are deemed by some to be crazy or abnormal – are actually some of the best, most non-judgemental people you will meet. I think of empathy as a painful euphoria, because it hurts like hell at times, but it is also something that no other feeling or experience can replicate.

So when the phone rings at 10.55 p.m., the time when I am usually in bed, putting my demons to sleep and going over my aspirations for the day ahead, I jump to answer it. I step out of my most peaceful place because I know a friend’s world is falling apart and, as someone who has lived through the same experience multiple times, I can help her. And over the next two to three hours, I hear the light coming into her voice. Which for me is the greatest feeling in the world. Every painful experience I have ever had then becomes a valued treasure – a currency for empathy, something that connects me to other people who need what I’ve learned. The things I once considered to be irreconcilable differences with humanity now become my means of bridging from my island to theirs.

Ergodicity is the mathematical theory for anyone who has ever felt alone, different, isolated or abnormal. Statistics is telling you that your individuality matters, as much as anyone else’s. It is a part of the weird and wonderful diversity that humanity relies on for its evolution and survival as a species. Quite literally, it counts.

Throughout our lives, individuality and conformity exert equal and sometimes opposite forces on us. The desire to stand out, and the need to belong, exist as parallel urges in all of us. We are individuals who can only survive and thrive in the collective context.

Everything I have studied about crowds over twenty years has led me to a clear conclusion. This is a duality we should embrace rather than seeking to fight. There is never any ultimate victor in the tussle to create equilibrium between me and we. Both have an essential role to play in our lives, and both must be respected. Both have something important to offer us.

What’s more, neither is going away. Our individual personality and character will always be in us, however much we might try to alter it. At the same time, retreating into ourselves as individuals doesn’t make the world go away. However much you might try to live on your own private island, there is no such thing as the entirely independent life. We have emotional and practical needs that can only be satisfied by tapping into the collective. At some point, even those of us who embrace our solitude have to leave our own shore, otherwise we never have anything to compare our solitary endeavours to. (And if you don’t relish the departure, it’s much more likely that you will enjoy the destination.)

As a child, this was something I feared above all other things. My mum used to say that going out with me was like a circus act, as I contorted myself to avoid the touching, and the sounds, noises and smells that scared me. But even though crowds still make me anxious and afraid, studying them has been one of my most important and beneficial experiments. It has helped me to recognize that individuality isn’t everything, nor is it something that you should ever deny or feel ashamed of. I can remain myself and keep hold of my personality, at the same time as being part of a wider world that I both benefit from and contribute to. Participating in the collective doesn’t stop me from being myself – in fact it makes the most of who I am, my experiences and what I have to offer. A dash of conformity has not detracted from my individuality, but deepened it.

My attempt to analyse crowds was born out of a need to cope with large numbers of people. But in the process I learned that I can do more than survive among other people. I can also connect and offer something unique. And the same is true for all of us.