8. How to have empathy with others

Evolution, probability and relationships

‘Don’t be so ridiculous, it’s only an umbrella.’

Except it wasn’t. To me, this solid little item wasn’t something expendable, to be left behind in a café and replaced without a second thought. It was my security, my armour for the day ahead, its neat, hooked handle a comfort to hold on to in all weathers. The umbrella wasn’t just to protect me from the rain: it could nudge away people who were getting too close and support me against stairway banisters I couldn’t bring myself to touch. Wherever I went outside, it came too: a mascot and a guardian. It was as important to me as a flash car or heirloom watch might be to someone else. Because the concept of money, other than as a means to survive, is mostly lost on me, the things I value are the few possessions that I trust as dependable companions. My umbrella was perhaps the most important of these.

And now it was broken, and the boy I was dating wanted to tell me it was only a silly bit of nylon and wood. He was unconcerned; I felt like crying.

The breaking of the umbrella might have been the breaking point between us. It threatened to be the moment that occurs in every failed relationship, when it becomes clear that one partner doesn’t respect or understand something that really matters to the other. As humans, too often we lack the empathy to see the world from someone else’s perspective, and impose our own beliefs on them. The gap grows between the person we want and expect to be with, and the one we actually are.

I told you, it was much more than just a silly old umbrella. The boy in question quite quickly cottoned on to this, so ended up outlasting my beloved brolly. But I had been reminded, yet again, of the difficulty of sharing a life with someone when you live in fundamentally different worlds.

Relationships, whether romantic or otherwise, are something I have had to work hard to understand and navigate my way through. Living in my own head is difficult enough, without having to do the same in someone else’s as I try to work out what they are thinking, what they mean and what they want. In fact, you might find it strange that I am talking about the importance of empathy, a subject on which us Aspies are supposed to be clueless. If there is one phrase you get sick of hearing, it is, ‘Try to put yourself in their shoes.’ The assumption is that, being autistic, we need all the help we can get to feel empathy and relate to other people.

But if I’ve learned one thing, it’s that people who are good at talking about the need for empathy often aren’t much good at showing it. Whereas, although I might not understand why someone thinks or behaves a certain way, you’d better believe I am watching closely and trying to figure it out. A lack of innate empathy means you have to work that much harder to divine people’s intentions and expectations. Through my eyes, a relationship becomes a complex equation of trying to match my behaviour to someone else’s anticipated needs. It’s empathy by observation, calculation and experimentation.

That makes it sound simple, which it definitely isn’t. Trying to understand, anticipate and respond to the whims of our fellow humans is one of the toughest jobs we have. The most serious detective work many of us will ever do is trying to establish what a hint of body language or an ambiguous phrase from a loved one actually means.

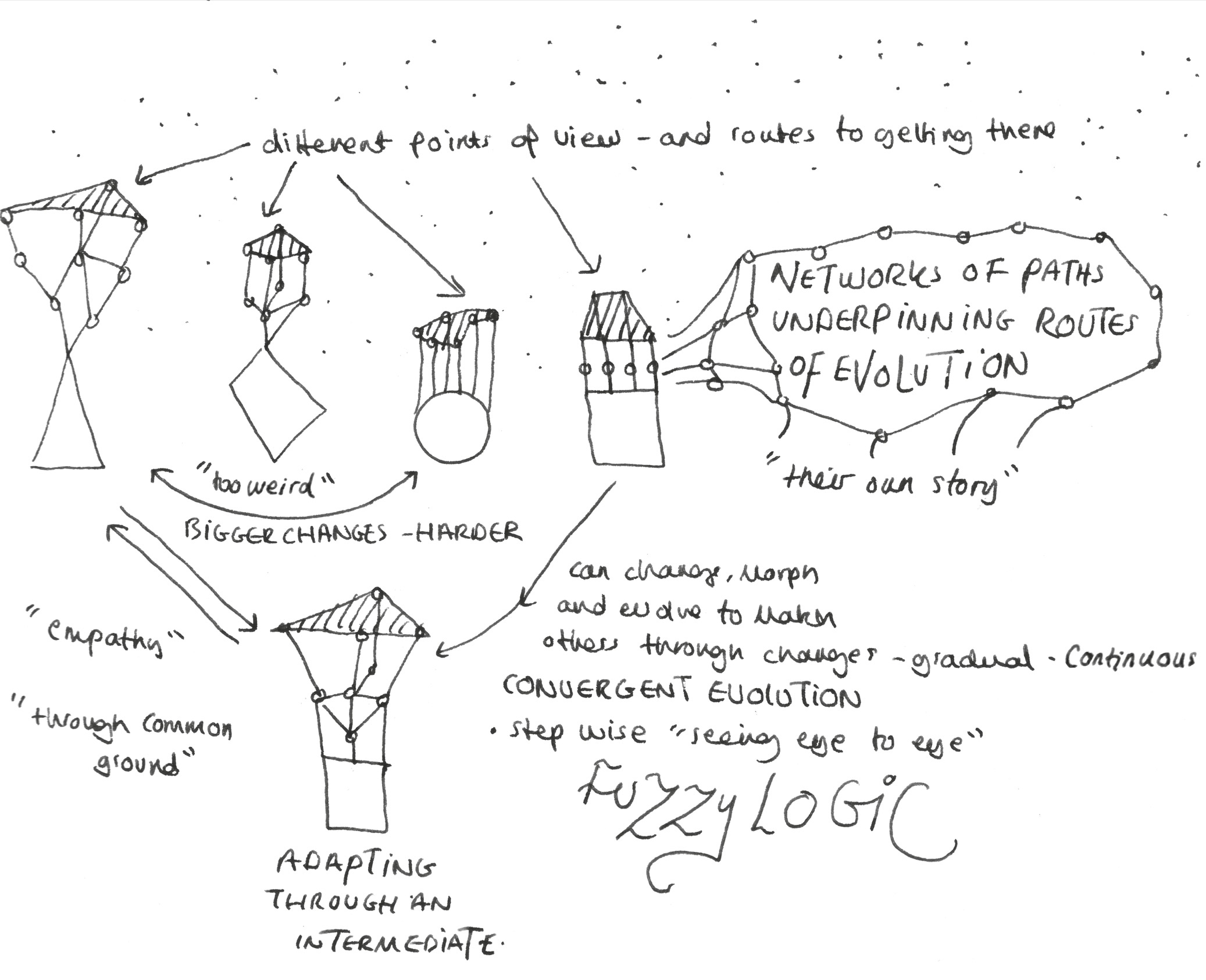

For this task, we need the best that science has to offer at sifting signals from noise, and deciding how to respond when the evidence is unclear. All relationships depend on an ability to read between the lines – to judge when it matters even if someone says it doesn’t, or when something might not seem important but really is. To make these precise judgements, we need to fine-tune our understanding of evolutionary biology, acknowledging where our differences stem from, and how a relationship between people will evolve over time, just as our bodies did from a single stem cell. We need to harness probability theory to help us decide what is and isn’t relevant evidence. And we can benefit from fuzzy logic (yes, that’s the technical term), as a framework for judging a decision when there is no black-and-white, yes-or-no answer; and for managing the inevitable conflicts that crop up in any human relationship.

The empathy we need to build and sustain relationships is something we can find by looking at the fundamentals of how we develop as humans, and conversely, by adopting some of the techniques that have been designed to help machines function in a human world. For our relationships to prosper, we have to be not just at our most human, but at our most mechanical: able to calculate and consider as much as we feel and relate.

Getting started: cellular evolution

Both the strengths and weaknesses of our human relationships are based on difference. We are all shaped by our different genetics, diverse experiences and varying outlooks on life. Yet despite these numerous contrasts, we once all started as essentially the same thing: an embryonic stem cell, one that endlessly divided and divided to create the skin, organs, bones and blood that hold us together.

Stem cells are the ultimate in evolutionary wonder: single entities that can divide and specialize into any of the cells needed in the human body (multi- or pluripotent, if you want the fancy word). For example, all of the blood cells in our bodies have ultimately diverged from a common stem cell, via a process called haematopoiesis (one of my favourite words). This is something that’s going on in your body right now, as we are topped up daily with the right balance of red blood cells to transport oxygen, and white blood cells to constantly update our immune system. It’s their ability to split, re-form and renew that makes them the essential building blocks of humanity, and such an important part of medical treatments for blood and immune system disorders – helping to rebuild the body they created in the first place.

A stem cell is the foundation for every human, and it’s also the ideal lens through which to better understand empathy in human relationships. Like a stem cell, every relationship essentially begins as a generic, unspecialized entity: two people seeing if they might like each other. Over time, where the stem cell divides into endless daughter cells with their own very specific uses, a relationship also becomes more defined and complex: an intricate web of shared experiences, understandings, language and unspoken meaning. Just like the stem cell, our relationships keep on specializing and differentiating over time – undergoing more mitosis (division) to meet newly encountered needs.

As we age, the repetition of this process starts to take its toll on our bodies. Every time a cell undergoes mitosis, it loses a little of what is called the telomere, the protective surface on the chromosome, capping the end of each DNA strand. In a process often likened to the gradual fraying of a shoelace, the telomere gets a little shorter with every division, until eventually it can no longer guard the DNA effectively, and the cell loses its ability to undergo mitosis and becomes senescent (inert). The tangible effects of human ageing, as our skin wrinkles and our organs begin to fail, is a function of this cellular withering. Over time, our cells wear out and our body gradually loses the ability to repair itself.

Our relationships are subject to the same threat of decay, likely to die out if we lose the ability to undergo emotional mitosis, continuing to evolve and specialize in changing circumstances – as both our needs and those of our partner change. At the other extreme, a relationship can go too fast and become too intense to bear, in the same way that a cell which has mutated and can’t stop dividing has become cancerous, growing out of control and starting to attack the body.

Understanding cellular evolution has helped me to realize two things fundamental to maintaining good relationships. The first is about respecting our differences. We might all look broadly similar and be part of one species, evolved from essentially the same ball of cells, but the devil is in the differentiation. Our endless evolution from that first embryonic stem cell has turned us into very different people. Often, it seems that the success of a relationship comes down to the ability of people to first recognize, then respect, these differences. It’s through our empathy with other people that we are able to establish the most meaningful connections, showing that we have really understood the people we care about, listening to what they are telling us not just in words but through small everyday gestures and non-verbal indicators. This at times may even involve eye contact. (The things I do for human connection.)

Our closest relationships are those in which we can rely on these things in abundance – allowing us to feel known, appreciated and loved without reservation. So when my sister was getting married, and I had to pick an outfit for the big day, we both instinctively recognized the scale of the challenge. I knew how important it was to her, as someone who works in fashion, that the choice was a good one. And she knew how much I hate shopping, and that I was prevaricating not from a lack of care, but because I simply didn’t know what to do. Being sisters we understand each other, so I was saved the ordeal of a solo shopping trip, and she was spared having her maid of honour turn up dressed, after Jim Carrey from Dumb and Dumber, in an orange tuxedo and top hat. (‘Don’t wear a top hat.’ ‘But you said I could wear anything I want, and you love Jim Carrey.’)

The second lesson from cellular biology is about patience. Just as it takes the embryonic stem cell nine months to gestate, and then a newborn baby up to eighteen years to complete its physical development (and a few more, neurologically speaking), a mutual understanding in a relationship cannot fully mature overnight. If, on the second or third date, we are already starting to envisage the life we might share with this person, then we are imposing the expectations of a mature entity onto one that has barely started to develop. That creates an asymmetry between what we expect of a person, and what they can reasonably be expected to know about us. The safer bet is to treat a nascent relationship as the straightforward, hardly evolved stem cell that it is. Try not to project all your big, long-term expectations onto someone right at the beginning. It’s all going to come crashing down if you ask too much too early of someone you haven’t yet shared spoons with. Be understanding and have the patience to realize it takes time for the evolutionary process to bear fruit.

Probability and empathy: Bayes’ theorem

The beginning of a relationship is really the easy part. As long as you don’t let your expectations run ahead of reality, it’s a time to enjoy the simple pleasures of something new and as yet unevolved.

But if you get beyond the honeymoon weeks and months, the realities of evolution must set in. As we get to know someone better, the single-celled organism of the first few dates starts to divide into something more complex. We acquire knowledge and shared experiences, and with them come expectations – that one person will know the other’s mind, be able to respond to their whims, and anticipate their needs.

People sometimes talk about a relationship falling into the comfort zone, where partners stop paying proper attention to each other, but if anything the opposite seems to be true. If ignorance was bliss, then knowledge means responsibility. The demands on your empathy rise fast as the evidence you collect about each other starts to accumulate.

It’s at this point, after we are meant to have got to know someone, that the real detective work begins. We are required to interpret small signals, half-hints and even complete silences. That’s a potential nightmare for anyone, but especially when ambiguity isn’t your strongest suit, and you are minded to take everything you are told completely literally. As an Aspie you have no preconditions or preconceptions when meeting someone: everyone gets seen with totally fresh eyes. So I needed a technique that could overcome my tendency to believe everything I was told, and my inability to naturally infer meaning from hints and signals. In this, Bayes’ theorem has been my trusty ally. This is a branch of probability theory, concerning how we can use the evidence we gather to continuously evolve our estimates of how different situations might develop. In other words, as a situation changes, so too does your appraisal of the various probabilities.

As a Bayesian, your starting point also differs from classic statistical techniques. Rather than simply inferring probabilities from the data you collect – for example, the chances of a particular coin landing heads or tails, based on an experimental sample of it being tossed – you start with a series of prior assumptions. You use things you already know to help calculate the probability – which in the coin example might include the technique of the person flipping it, or the possibility that they are somehow trying to influence the result. Bayes’ tells us not just to collect data and draw linear conclusions, but to put it into the wider context of everything we know about the situation in question.

Hold on a minute, I can hear you thinking. Isn’t this the very opposite of what scientific research should be about: putting your finger on the scale instead of letting the evidence speak for itself? Well, it’s certainly true that if your assumptions are wildly skewed, then so too will be your interpretation of the evidence. But there is also a simple but compelling power to the Bayesian approach: it lifts our sights beyond a narrow, time-limited data set, allowing us to widen our field of vision and put issues into a context that can otherwise be easily, and fatefully, ignored. For instance, it helps identify errors in medical screening: a test that may be 99 per cent accurate doesn’t mean we have a 99 per cent chance of carrying a disease just because we have tested positive, but we only know this by using our prior knowledge about the prevalence of false positives.

Bayes’ theorem allows us to consider everything we know about something or someone: when used properly, it is a brilliant technique for squaring the circle between what we know and what evidence tells us – exposing both potential flaws in our assumptions, and limitations in the data we collect. In other words, it helps the evidence to improve our assumptions, and the assumptions to improve how we use evidence. It’s also important not only in how we approach questions of probability – making use of our prior, contextual knowledge – but also in how we update our assumptions as new evidence accrues. This is what’s known as conditional probability – the chance of a certain outcome based on events that have happened, or still might.

Whenever I encounter anything new in my life, be that a relationship, a change of environment, or a new job, I use Bayes’ theorem to help me navigate new uncertainties, and to tune into an unfamiliar culture and norms. I try to rid myself of my own biases and become a scouter, living based not on my own carefully curated preferences, but according to those that seem to be representative of this new system. When I went to university, I even put myself through the Aspergic nightmare of going clubbing: the deepest, darkest place no Millie Pang had ever been. I danced through it. And I collected data that was essential to giving me the new context I needed to interpret all the unfamiliar situations I was encountering, and the new experiences that were contained within them.

The same approach can help us when trying to find our feet in a recent or evolving relationship. If we want to really understand someone, we need to observe them carefully, learning about the differences between what they say and what they mean, how they behave when they are happy or sad, what it means when they retreat into their shell (which could be signalling a problem, or simply be an expression of their desire for space). That honeymoon period, when expectations are low? That’s the time to be gathering all this evidence for when you will later need it. Someone will forgive you early on for not realizing that ‘Sure, fine’ means ‘Definitely not’, but over time that tolerance ebbs. The stage in a relationship at which we seem to have most latitude is actually the one where we need to be paying close attention – something that will pay off in the long run.

Of course the other inference of Bayes’ theorem is that, because prior assumptions matter in how we interpret evidence, two people are likely to look at the same question differently. We need to have the empathy to understand that what seems like an open-and-shut case to us, could be the opposite for our partner – if they are starting from a different place of acquired knowledge, judgements and experience.

I also use Bayes’ theorem to help manage the most tempestuous relationship in my life – the one with myself. However bitter an argument might get with a friend or partner, it’s nothing compared to the raging tempest that is going on in my own head. Because my brain is having to work overtime to process all the data around it, considering everything from every possible angle, it becomes a pressure cooker which can boil over without warning. Sometimes there’s no alternative but to let out some of the noise that is pounding through my brain: banging my head against the table, screaming and shaking, running around in circles. Anything to release some of the pressure of just trying to exist.

As well as routine to provide my anchor, Bayes’ theorem has been my weapon in this very personal war. Rather than simply responding to the evidence in front of me – the noise, smell, or sight of a plastic button that would alone send me into meltdown – I can use my prior assumptions to drag myself back from the brink. That horrible smell can’t really be so bad, because someone farted in class a week ago and I didn’t die. The probability is, difficult as this might seem, that I’m going to be OK. Bayes’ theorem has helped me to prioritize the different triggers that threaten my equilibrium, and separate the ones that are emotionally important from those which are just habitual pain points. It allows me to pick my ASD battles, and conserve some much-needed energy.

Human behaviour, whether our own or someone else’s, is never wholly predictable and can’t be quantified absolutely. But we can treat it as a question of probability, fine-tuning our knowledge and assumptions about the people in our lives, and using those to determine how we respond in different situations. Turning your partner into an object of scientific study might not sound sexy (to some), but it’s the surest route to achieving empathy that I know. We have to do this because of the simple, and annoying, fact that people usually don’t tell you what they actually want. They hint at it, signal it through body language or simply expect you to work it out. A nightmare when your mind, like mine, demands clear and unambiguous evidence to work from. Only by harnessing probability theory – applying what we know to the question of what someone actually wants, and what might happen next – can we truly find a way through these grey and misty parts of every relationship. So if you didn’t know that an eighteenth-century Presbyterian minister (Bayes himself) was the best relationship counsellor you’re going to meet, you do now.

Argument and compromise: fuzzy logic

Observing the people in our lives is one thing, but that only gets us halfway to solving the mystery of how we can meet both their needs and ours to build a healthy relationship, making the necessary compromises and overcoming the inevitable disagreements. We also need to be able to interpret the evidence we collect through observation, and take decisions that help to create equilibrium over time. This is where we can make use of one of the most important principles in artificial intelligence and computer programming: fuzzy logic.

You might assume that algorithms are a bad place to start when seeking techniques to navigate the grey areas in life. Isn’t this the one field where the human mind is, and will remain, superior to the machine brain? Well, that would be the case if we were capable of using our maximum capabilities to discern complex situations, deploy empathy and make perfect relationship judgements every time. But unless that applies to you (and it certainly doesn’t to me), it’s worth taking a look at how the developers of machine learning have been grappling with just this problem. Perhaps an idea that’s designed to help machines think more like humans can help us to do the same.

Fuzzy logic is the technique used to help an algorithm operate in situations where there is no certain truth, and not every factor can be categorized as either 0 or 1 – be that left or right, up or down, right or wrong. It allows a program to calculate in between the binaries, estimating the extent to which a non-absolute proposition is the case – for instance, whether something tastes nice or not. With fuzzy logic, an algorithm can determine whether something is mostly true or not, on a sliding scale between 0 and 1, rather than having to choose one definitive answer or the other. This has endless applications in developing automatic systems – from car braking that needs to determine how close the vehicle in front is, to washing machines that can adjust the flow and temperature of water, and the volume of detergent, during the cycle according to how dirty clothes are.

It also has applications in game theory and conflict resolution, as a methodology for mapping an ecosystem of different people with varying preferences, which may fluctuate between 0 and 1 – from absolute conviction to being totally willing to compromise – over the course of a negotiation.

It’s this application that is most relevant for our personal relationships. However much you like or love someone, we all have arguments. The question isn’t whether they will occur, but how ideally to manage them. Fuzzy logic holds the key, because it tells us that the human urge to ‘win’ an argument is pretty useless. If something is worth arguing about, i.e. one person isn’t willing to admit fault, then it’s unlikely to exist at either the 0 or 1 end of the scale. Usually, it is in the grey area. Perhaps both of you need to apologize, or maybe there isn’t a truly right answer about whether to get the new sofa in blue or red. An argument isn’t a game, but more a problem to be solved, like a game of 3D Tetris in which you need to make the moving parts of your contrasting opinions fit as neatly together as possible. This is something I found because I’ve never been very good at ‘fighting speech’, and often didn’t even understand the insults that other people would throw in my direction. That said, I can give it back in my own way: I’m no stranger to sharp opinions, and since I was described by someone at work as ‘terse’, it has become one of my favourite words.

We get into arguments for various reasons. Sometimes it’s because we’re bored – either in the moment, or of the entire relationship – and pick a fight to challenge and stimulate ourselves. But most of all, we aren’t being bad actors or manipulators. We actually believe ourselves to be right, and our partner mistaken: a classic mismatch in intention and interpretation that is like clashing pieces on the Tetris screen. We argue from a conviction that our assumptions and interpretations deserve to prevail. And we demonstrate a lack of Bayesian empathy about what the other person may be feeling or thinking, or the accumulated experiences and assumptions that have led us both to contrasting perspectives.

At this point, you can either engage in a shouting match and door-slamming competition, or you can allow your thinking to become fuzzier. You can accept that there is no binary right and wrong in the issue at stake. And, like the smart washing machine, you can adjust for the context. Maybe this isn’t something worth having a proper row about. Perhaps you can alter what you thought was a strongly held view, because it simply isn’t worth it in the context of the relationship. Or you might just have to accept that you aren’t going to get what you wanted on this particular occasion, and it doesn’t matter as much as you thought it did. Conversely, there might be some things that genuinely are significant to you, which your partner doesn’t immediately understand (aka my umbrella). It’s in these cases that you need to seek a compromise, rather than offering one.

The most important thing is to lose neither your Bayesian nor your fuzzy-logic perspective. Something isn’t ‘obvious’ unless two people are looking at it from an identical starting point. Your belief that you are 100 per cent right about something may fall apart the moment you realize that this only holds when seen through the lens of your own unique perspective, based on assumptions and experiences your partner may not share. Having fuzzy arguments helps get us away from the flashpoints of binary thinking and rash statements – instead slowing down to consider all the options. It’s difficult to do during an argument, when emotion is at the forefront, but if you actually want to reach a conclusion it’s the better way.

Arguments can be a healthy part of any relationship. We all need the chance to air our feelings, much as a computer has to debug, identifying flaws and shortcomings so it can work more effectively in the future. An argument done well – respectfully, and fuzzily – can serve as a debugging process on issues that may have been inhibiting a relationship. It’s an opportunity to show both empathy and vulnerability: revealing more of each other’s emotional and personal tapestry, and understanding your evolution as people. But that can only happen if we learn what machines are now being taught – that when there is no absolute right or wrong, we need to find a way to live and make calculations in the grey space between. Understanding our biases, and being willing to flex our convictions in light of that self-knowledge, is crucial to helping any relationship over the hurdles of argument and disagreement. If you still love someone after you’ve had reason to hate them, then you have what I call an ideal relationship: something that only the unfolding of evolution can reveal. And the best part is, I’m as incapable of holding a grudge as I am at detecting irony or making assumptions about people. Five minutes after the argument has ended, I’ll be in the next room offering you tea. Until next time.

At times in my life I have wondered if I am allergic to people, so strong has my negative response been to someone else’s smell, touch or words. I physically flinch from behaviours I find threatening – which, you’ll have worked out by this point, is a lot. I’ve often despaired at my ignorance towards my own species: my inability to relate to other people, or to feel part of their world. Much like my immune system itself, I am constantly updating my mental immunity to handle and embrace the evolving changes of people and life. Some changes are small and easy to fix and at other times it is a battle akin to curing the common cold.

But I also know, deep down, that it’s love that makes us feel alive, even when it’s inconvenient, painful and hard to bear. The mathematician in me is also a romantic. She believes there are ways we can use statistics, probability and machine-learning techniques to improve our search for love and harmony with the people we care about. And if you’re sceptical about the role of data science in your love life, then I would ask if you’ve ever used Tinder, Bumble or any other dating app. Because the truth is that many of us have been sharing a bed with AI for some time.

Relationships may be far from a science, but there are many ways in which science can help us to manage them better. One is in understanding the vital importance of evolution – how it got us to this point, and how important it continues to be in all our lives. A relationship is never static and cannot be treated as such. It has to be respected as a dynamic entity, containing two (or more) people whose needs, wants and hopes are going to continue changing over time. Biologically, we are all hard-wired for evolution: it’s what got humanity from cave dwelling to modern living, and transformed every one of us from a zygote in the womb to the adult human we are today. But we don’t always understand or acknowledge evolution in our adult relationships. We behave as if people haven’t changed over the course of several years, or as if it’s inconceivable that they might. We don’t always work to ensure that our expectations, assumptions and behaviours evolve to match how someone else’s life is changing. So the first point is to be more conscious of evolution in relationships – our own and our partner’s – and to respond accordingly.

The second is to accept the uncertainty and ambiguity fundamental to any relationship, and to find ways to work with it, rather than fighting against it. We can’t simply demand of people that they be 100 per cent honest and clear with us all the time (much as I would really, really love this). We have to be smarter than that – closely observing a partner’s behaviour to give ourselves the context and data we need to assess probabilities. Becoming better observers will make us better Bayesians – and ultimately more empathetic partners.

On top of being more evolution aware, and more probability savvy, we should be bias conscious: clear about how our opinions are shaped by our experiences, and how different two people’s perspectives on the same issue can reasonably be. Fuzzy logic – an acceptance that the answer to most difficult questions lies not at either pole, but in between – is fundamental to achieving compromise and turning arguments into positive experience, not destructive ones.

We have all made mistakes in relationships, had regrets, and sometimes wondered what is wrong with us. We shouldn’t beat ourselves up. Humans are complex enough beasts on their own, let alone trying to work together in a pair, or as part of a pack. But we can do better if we take a step back, and use some new lenses to look at the same old problems. Empathy, understanding, compromise – all these are things we are told we need to show in order to build lasting relationships. And all of them can be improved and enhanced through the kinds of techniques I have discussed. Believe me: if I can do it, anyone can.