9. How to connect with others

Chemical bonds, fundamental forces and human connection

Of all my school subjects, English was the one I always found hardest. At sixteen, I was categorized as having a reading age of five: not because I wasn’t literate, but thanks to my over-literal interpretation of some questions in a comprehension test. (They asked what happened when a ball was kicked through the window; I wanted to know whether it had been open or closed.)

I would sit in a specially chosen spot that placed me as far from the teacher and as near to the door (and radiator) as possible. A five-star seat for a one-star class. My ADHD would spike as my mind pogoed from boredom to restlessness. As the latest passage from Of Mice and Men was read out, I would doodle my own version of the story, the only way I could understand the connections between characters and different parts of the narrative: a little language blending maths, art and literature that was all my own. My classmates, I could clearly tell, were mentally doodling as they zoned out from the reading. But it was my scribbles that caught the eye of my least favourite teacher.

‘Camilla! It seems as though you are doodling again. Tell me, how would you describe the relationship between George and Lennie?’

‘Tan(x), all the way.’

At this, quite a few woke up from their doodling and laughed. Emboldened, I continued.

‘The tan(x) curve is one which demonstrates periods of great turbulence with short, calm plateaus in between; also harbouring a great contrasting symmetry, which at certain points contains regions that are polarizing, unapproachable and undefinable – asymptotes. I can see this about their brotherhood. It is almost magnetic.’

This, it quickly became clear, was not the desired response. I was castigated for not taking the book seriously, distracting the class, and even being a disgrace to literature (impressive, for someone who had barely read a novel at this point). As the teacher completed her rant, every head in the class now facing my way, she moved closer to the point where I could smell her breath. The tense silence and sharp odour triggered such an anxiety in me that I panicked, squatted under her armpit and sprinted through the door, hands over my ears.

But after the immediate panic had subsided, I started to feel triumphant. Out of the chaos of that moment, a new idea started to bubble to the surface, effervescent with possibility. My sketching, and unusual venture into literary criticism, had actually led me to something important. Thinking about the relationship as a trigonometric curve had sparked an epiphany. If a human (admittedly fictional) relationship could be represented like this, perhaps there were other ways maths and science could help me to understand the mysterious nature of human connections and relationships. These are the moments I live for, when I suddenly see a link between a scientific idea I know well and a human problem I have been struggling with.

The obvious place to start was bonds, the chemical attractions that link atoms and molecules together, and quite literally hold our world together. If people can be connected to each other culturally and emotionally, that is only possible because of the millions of microscopic chemical and electromagnetic bonds that hold our world and our bodies together. It is bonds that explain everything from the air you are breathing to the water in your glass. Without bonds, we and everything else would quite literally fall apart.

As well as being intrinsic, bonds are illustrative. Just as there are different types of relationships, there are also different types of bonds with varying properties. There are strong and weak bonds, temporary and permanent ones, some that are reliant on attraction and others that depend on a union of differences. What’s more, like our human relationships, chemical bonds do not exist in isolation. Their existence and evolution are shaped by the fundamental forces that surround them, sucking them together, pulling them apart or moving them in different and unexpected directions.

What began as a classroom daydream has turned into one of my most important tools for understanding relationships of all kinds. Using bonds and force fields as my template allows me to model different relationships – explaining their shape, nature and purpose – and to understand the various directions they take, as you become closer or more distant with people over time. Crucially, it has allowed me to see that relationships are different. There are many kinds, with their own properties and features, which tell you something important about what expectations to have. Scientists rely on their knowledge of bonds to understand how different atoms, molecules and systems will respond to each other and react together. As people we could benefit by taking the same approach: understanding that, while no two relationships may be identical, there are broad categories which can tell us about the likelihood of different outcomes.

If we know more about the bonds that connect us with the people in our lives, and their distinctive properties, we are in a much better place to manage the evolution and growth (or demise) of our relationships over time. This one’s for people who have wondered why a friend abandoned them, or who agonized over how to break up a relationship that had lived beyond its time. The answer lies not entirely in our actions and personality – or those of the other person – but in the nature of the bond that connects us. If we can understand that, things slowly start to make sense.

Introducing chemical bonds

All around us are chemical bonds, connections we can’t see that allow everything we can see to function.

Bonding is the foundational activity of all chemistry. It’s what allows atoms to join together, forming the molecules that – as we learned earlier – create structures such as proteins, the building blocks of the natural world.

Like in a human relationship, bonding involves the business of give and take – in this case, of electrons. These are one of the three kinds of subatomic particles that make up every single atom. In the nucleus (centre) of an atom you have positively charged protons, alongside neutrons, which carry no charge; while in the outer shells sit the negatively charged electrons. Together, these contrasting electrical charges mean an atom is constantly engaged in an internal tug of war, trying to achieve balance between competing forces – much as humans do in our own heads.

It’s the exchange of electrons that defines the need for chemical bonding: to join with other atoms in such a way that will create a more stable overall structure: a compound. Other than the noble gases such as helium, very few atoms have the right number of electrons on their own to achieve peak stability. So they look for others to bond with, in ways that will complete them (aww).

In this, atoms are really no different from the people they ultimately create, looking for others to form connections with for a happier and, perhaps, easier life. And, just like our human relationships, the way they come together varies. Sometimes there is a true meeting of minds, in the form of an electron being shared; others happen when one atom gives up an electron for the sake of another; still more are the product of the electrical charges created as electrons are traded.

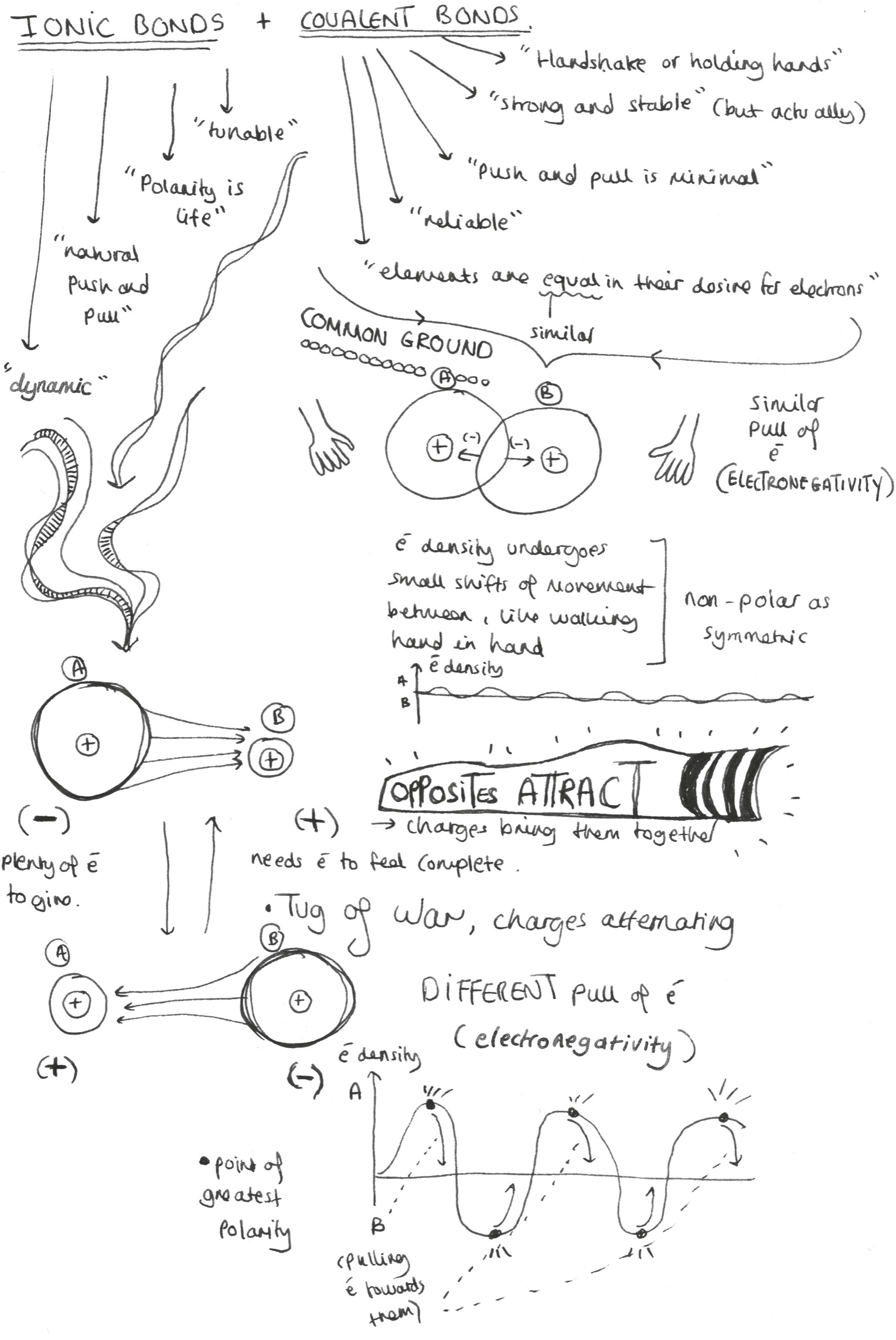

I believe there are clear parallels between the different kinds of bonds atoms form, and the relationships we create in our own lives. In understanding this, there are two main bond types to be aware of.

Covalent bonds

The most mutual form of chemical bonding is covalent, whereby two or more atoms share electrons in order to complete their outer structures. Within the outer atomic shells, the magic number is eight, the requisite number of electrons to achieve stability – a state in which the electromagnetic push and pull between the nucleus and the electrons is minimized.

Hence atoms are engaged in a sort of chemical speed date to find the right partner or partners to fill their quota. Take one compound we are all breathing in right now: carbon dioxide or CO2. This comes about through a single carbon atom of four electrons sharing two electrons each with two oxygens, giving them both a stable eight.

Covalent bonding is an exercise in stability through sharing – a collaborative effort to create a chemical balance where both (or all) partners need each other equally. These bonds reflect the relationships in our lives that are based on common understanding and shared principles or values: where there is an innate symmetry that creates a long-lasting connection, and minimal drama or volatility. When you meet someone and feel like you’ve always known them, then you know how a covalent bond feels. The friendship is tight, immediate and reassuring.

Ionic bonds

Where covalency is about mutual dependency, ionic bonding relies more on give and take. Here, there is a transfer of electrons from one atom to another, creating an electrostatic charge that holds the atoms together.

In the case of another familiar everyday element, sodium chloride or NaCl, this happens when sodium donates the single electron in its outermost shell to chlorine, which has started with seven. Through this process, sodium becomes positively charged and chlorine negatively, and the two bond together through the attraction of their opposite charges. That’s how you get table salt.

Ionic (or polar) bonds are those which are based on the attraction of difference. They are less about complementarity than the transfer of power. These are the relationships in which you know the other person may be totally different from you, but there is an interest or attraction that unerringly draws you closer to them. Ionic bonds are stronger than their covalent cousins, taking more energy to break apart – i.e. they have a higher melting or boiling point. This means that although an ionic relationship might be more emotionally volatile, in chemical terms ionic bonds are actually more stable. This natural asymmetry reflects the balance of power in a friendship, which in a healthy relationship equalizes over time through natural exchange and swapping.

The different kinds of bonds (these are the main ones, but there are further subcategories) show how the nature of the connection between us can govern so many different elements of a relationship: whether it is inherently strong or weak, formed from differences or similarities, and based on power sharing or a power imbalance. Like relationships, compounds can be complicated and formed of different kinds of bonds together. The best example is water, whose core compound (H2O) is the product of two hydrogens (1 electron each) bonding covalently with an oxygen (6). But it doesn’t stop there, because the hydrogens continue to be attracted to neighbouring oxygen, forming additional ionic bonds – a combination known as hydrogen bonding. It’s this mix of ionic and covalent that makes water one of the most versatile and accepting molecular mediators. Hydrogen bonds are akin to those you might have with work colleagues or teammates in sport: often not as strong as the connections with best friends or family, but essential bonds that can adapt to a wide variety of situations.

Just as protein personalities can help us to understand the different dynamics of a social group, understanding individual polarities is key to determining how people like to form relationships. There are extroverts who want to donate electrons, and introverts who would usually rather receive. And then there are the human equivalents of the noble gases – those whose electron shells (personal lives) are already complete, and have no need or desire for further interaction. Much as atoms go searching for one or multiple dance partners depending on their electronic need, different people may be searching for one partner to complete them, or for many friends to bond and connect with. This connective outreach, or atomic bonding potential, is referred to as their valency.

The hydrophobic effect

Conversely, there are people we can never get on with or to whom we become actively opposed – and bonds explain these antagonistic relationships as well. Think about when you add some drops of oil to water. Polar water comes into contact with non-polar, low-density oil. The result is that the two molecule types would rather interact with themselves than with each other. This is called the hydrophobic effect, and it explains why you should never drink water after eating spicy food. Instead of binding with non-polar capsaicin, the key compound of chillis, to wash it away, water simply flows past it – spreading it around your tongue where it binds onto even more of its receptors, heightening the burning sensation.

The hydrophobic effect also helped me understand the closed nature of some friendship cliques and the antagonistic attitude of bullies at school. People who won’t let you into their circle, or who actively try to hurt you physically or emotionally, are defined by their unwillingness to bond. They have their atomically stable social structure, and want to continue interacting within that, keeping you on the outside. Human hydrophobia of this kind is about unstable atoms that bond together with others like them – defined by their non-polarity, the unwillingness to connect to others who might undermine the uneasy stability the group has created. What binds them together is a shared fear: of judgement, inferiority or rejection. Like the oil, they cluster together but remain isolated in the wider mix, fearing that to bond further with different people would pull apart the connections they have so far managed to form. As such, the social cliques that seem so desirable to our younger selves are often expressions not of strength and confidence, but weakness. They represent the fear of being shown up or outclassed by other atoms. Their defining feature is not what holds them together, but the mindset that compels them to stand apart.

As much as bonds provide us with a map for making connections, they also indicate where it isn’t going to be possible – because you are dealing with fundamentally non-compatible molecules, who simply don’t want to play together. If people aren’t willing to come out of their atomic shell, there isn’t much you can do. Bonds also reinforce the importance of balance in any relationship. Remember that every atom has a nucleus filled with positively charged protons, with its negatively charged electrons orbiting outside. When atoms get drawn together in an ionic bond, the two nuclei come closer together, with the distance between them being known as the bond length. The shorter that length, the stronger the bond. Unless, that is, the two nuclei get too close together in which case the protons start to repel each other. Just like when a friend or partner has become clingy, or dominating, or accidentally walks in on you having a number two – there comes a point when you need to re-establish boundaries. Bonds remind us that you can be both too distant and too close to someone to form an effective, stable relationship. It’s all about finding the healthy middle, and understanding the inherent volatility of the bond you have forged with someone.

If you are looking to make friends, or find a partner, it’s essential to understand both your own valency (combining power) and that of others. This helps you to judge what kind of connection you are likely to form, whether you are being asked to give, take or share a part of yourself, and what kind of relationship you have ultimately formed: on a spectrum from calm, mutual covalency to emotional, highly charged but harder-to-break polarity. It also lets you decide whether or not you feel open and stable enough to form that kind of relationship.

Ultimately, we connect with others for the same reasons that atoms bond: for stability, security and to obtain something that we lack when alone. But we can only form those bonds if, like the atom, we make them with the right partners and for the right reasons – and have enough innate stability ourselves to maintain them.

The four fundamental forces

Chemical bonds do not exist in a vacuum. They are the products of their environment, and the various forces in nature that hold them together and move them around. Forces help to explain why atoms come together, and how they fall apart. They illuminate how pressure is exerted and its effects over time. If we want to understand not just how a connection is initially formed, but how it lasts, or fails to, over time, then we need to understand forces and how they work. Of these, there are four literal forces of nature that are considered to be fundamental:

-

Gravitational force: This is the weakest force, but with infinite range. We all know how gravity works: it’s the one that keeps us grounded. Without it, nothing would be anchored – you couldn’t sit in your chair, the coffee wouldn’t stay in your cup, nor the roof on your house. It’s the constant, reassuring force in our lives: the reason I like to work sitting with my laptop on the floor, where there is limited scope for anything to fall (as long as the ground beneath me holds). Because gravity is proportionate by mass – the greater the mass of two objects, the stronger the gravitational force between them. It’s a force in which the largest object calls the shots. In the solar system, the Moon orbits Earth because it is only (just over) a quarter of its size. But the Sun weighs over 300,000 times as much as Earth, therefore pulling it into its gravitational force field.

We need to be aware of the same propensity in our relationships: are we equal partners with someone else, or does one carry a much greater mass of age or personality, and therefore act as the gravitational core? This might create an imbalance in which one person overwhelms and inhibits the other, or it could be that you are seeking just this kind of anchor in your life, and will therefore be attracted to someone who bears a reassuring mass (perhaps of experience) that you lack. Whatever the case, it’s important to be aware that two people in a relationship are like objects imparting a gravitational force on each other, and to understand the equilibrium or otherwise that this has created. Usually there will be one person orbiting the other: it’s helpful to understand which is which, and whether that is right for you.

-

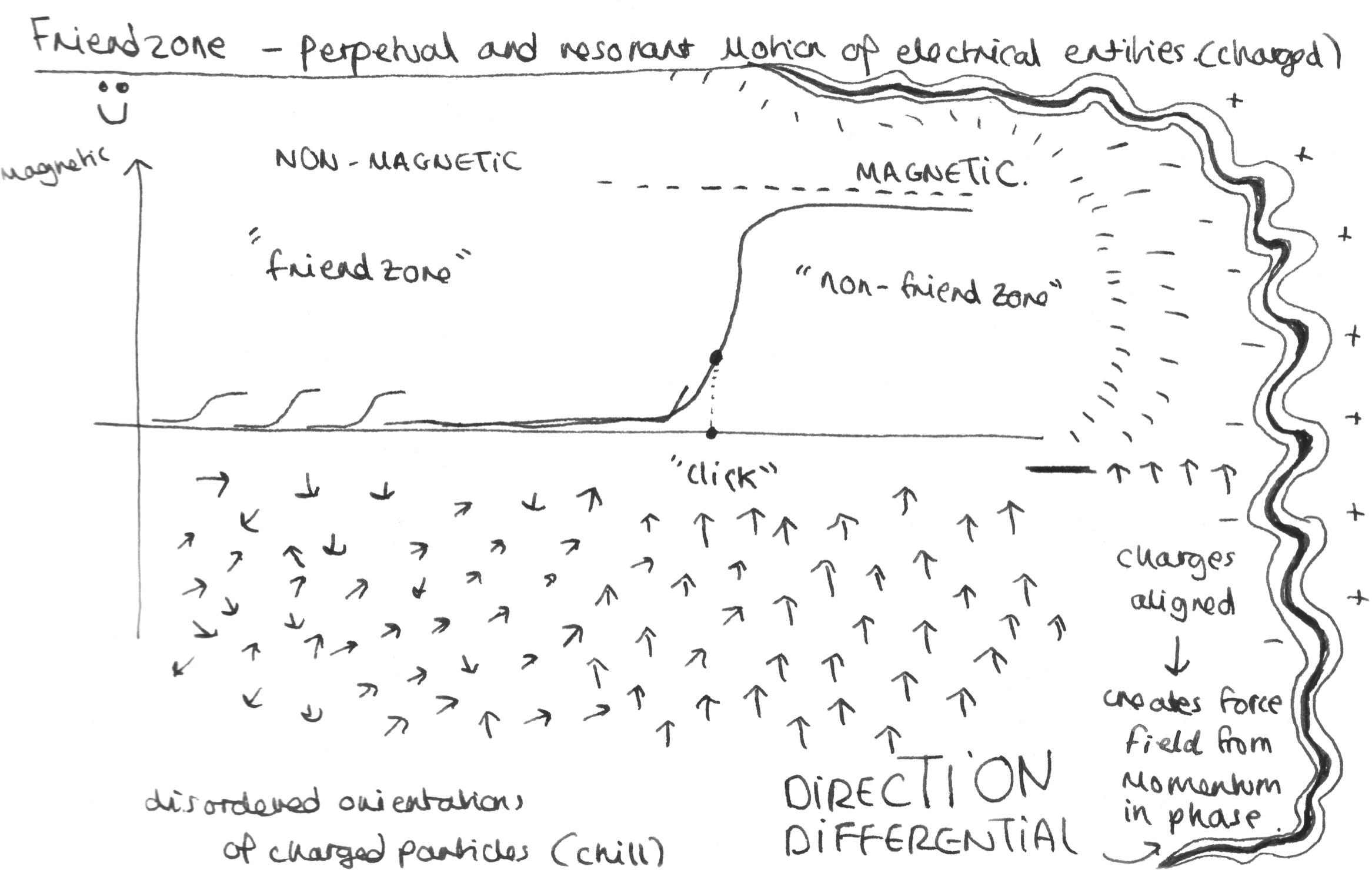

Electromagnetic force: Helpfully enough for a chapter about relationships, electromagnetism is science’s law of attraction, the force that brings objects together or drives them apart depending on the polarity of electrical charges. Electromagnetism, chemistry’s Romeo and Juliet, arises from two perpendicular force fields. There is the electrostatic charge, where two atoms quite literally have a moment – known as a dipole – when their inherent polarity forges a (hopefully not doomed) union. And there is the magnetism part, where the revolving motion of charged entities is so great it creates its own force field, and what was a chaotic group of particles becomes a coherent, directional entity with magnetic potential. It’s the power of these two forces working together that underpins physical magnetism, the natural world’s fundamental law of attraction.

As we have seen, the electromagnetic forces created by electron transfer are what create ionic or polar bonds. Given that our bodies are hives of electrical activity, it’s no surprise that we experience much the same at the macro level: an almost magnetic attraction to some people with whom we feel compelled to exchange electrons (and whatever else). These electromagnetic attractions can be stable or unstable, and because of their polar nature, they can be polarizing: excitable and highly charged. They are the essence of our most exciting relationships, those where the attraction is strong, some danger is present and there is always the threat of volatility. So if you’ve ever rolled your eyes at someone talking about ‘the spark’ in a romantic relationship, cut them some slack. They’re being more scientific than they realize.

-

Strong (nuclear) force: As you’ve been reading this chapter, one contradiction may have occurred to you. If so much of chemical bonding is to do with the attraction of oppositely charged particles and the repulsion of similarly charged, then what about protons? How do a bunch of positively charged, microscopic ping-pong balls hold together in the nucleus of every atom – doing literally the opposite of what their electrostatic charge compels them to? This is thanks to what’s known, with winning simplicity, as the strong force. It isn’t something you’ve heard of, but you’re definitely grateful for it. Without it all our atoms would fall apart and so would we.

Without going into too much detail, and introducing new friends that sound like rejected Doctor Who characters (quarks, gluons and hadrons), it’s sufficient to understand that the strong force both exists and is, well, much stronger than the electromagnetic one pushing the protons apart. So it’s the most powerful, but also the most limited in range. In human terms, I like to think of the strong force as analogous to the most intrinsic, deep-rooted and powerful values that hold us together: love, loyalty, identity and trust. Like the strong force itself, we can hardly see these things and may not fully understand them; but we know how much they are needed as our anchors in life. As important as the bonds we form with others are, one of the most fundamental factors in any life is the strong force that comes from within, holding us together when it sometimes feels as though all the world is trying to pull us apart.

-

Weak (nuclear) force: The final of our fundamental forces is one that affects how particles change and explains much of the instability inherent in some atoms. Not actually the weakest of the four fundamental forces (bad luck, gravity), it is also much more influential than its name suggests. Operating over a tiny range, it is the only force that can actually change the internal composition of the atom, promoting the decay of the nucleus. (For the record, it does this by changing the flavour – or type – of the quarks, which are the smallest measurable subatomic particles in your protons, neutrons and electrons.)

Weak force is responsible for atomic instability, which is often the source of significant energy releases. We need weak force to make the sun shine (it causes the hydrogen nuclei to break down into helium, generating massive thermonuclear force). The same is true of nuclear fission. As that implies, weak force can be the source of huge instability and destruction. In our lives, it is sometimes represented by the people who try to gaslight, guilt trip or otherwise chip away at our confidence and sense of self. Some people want to change you into a form they will be more comfortable with – to bring you to their level.

But in other ways the weak force is necessary, able to break down a bond that no longer serves its purpose, allowing us to move on from relationships that have become difficult or toxic. Sometimes breaking such ties is less an act of selfishness than one of self-preservation. As volatile as change can be, it also has the potential to unlock opportunity and personal growth. In the same way as there are fundamental forces holding and bonding us together, the weak force exists to pull us apart. You have to know when to resist, and when to accept it.

These four forces – the one that keeps us grounded, the one that creates attraction and repulsion, the one that holds us together and the one that enables things to fall apart – are fundamental to every element of our existence. And they provide a guide to thinking about how relationships come together, make us feel, and sometimes collapse without warning. They show us that it is the balance of different forces being exerted that is most important. When something doesn’t feel right in a relationship, it will invariably be because an imbalance has been created: perhaps one person has lost their magnetism, or is providing too strong a gravitational anchor to allow the other to express themselves and evolve. Sometimes the strong force that held a relationship together may simply dissipate. Or one of you may have been compelled by weak force to change in a way that no longer makes you compatible.

When we’re pondering what made us fall in or out of love with someone, or why a friendship that once really mattered has faltered, forces offer a good place to start. They allow us to consider more precisely what it was that brought us together with someone in the first place, and how and why those conditions may have changed. If the question is why something in your life came together or fell apart, then the four fundamental forces will usually hold the answer.

When things fall apart

If bonds provide a model for understanding how we as humans connect, they can also explain some of the reasons those connections fray and decompose over time.

No chemical bond is unbreakable. Every compound has its melting and boiling point, and the only real question is how much energy it takes. In the case of the ionic bonds holding sodium chloride together, a little water will do the trick, especially if it’s hot.

Dissolving salt into your pasta cooking water may not sound very similar to a relationship breaking up or a friendship souring, but the essence is the same. The conditions in which the bond exist have changed and, as the temperature rises, the connection is no longer strong enough to hold together. All of our relationships will go through changes in circumstances: whether they are strong enough to survive will depend on both the nature of the bond, and the degree of change.

The hydrogen bond of a casual friendship is unlikely to last one person moving country, for instance. Whereas, if you have developed an ionic bond with a work colleague, it’s unlikely that one of you moving jobs is going to stop you from being close friends. Your polarities as people haven’t changed, even if the circumstances of your relationship have.

One of the most frequent reasons you hear for people drifting apart is that ‘she/he changed’. We offer that simple, inadequate phrase to capture the full spectrum of personal evolution: how we change as we progress through life, enjoying success and enduring failure, and the imprint of our life experiences both good and bad.

Atomic compounds may provide a useful model to understand human connection, but of course we’re quite a bit more complicated than that. Our needs, personalities and goals are liable to evolve over time in a way that the outer shell of a carbon atom isn’t. It will always have its four electrons, and be looking for those two oxygens to complete itself with. As humans, our electrostatic needs are more fungible. We change, and with changes in personality, outlook and life ambition can come a change in valency. Looking for different things may mean looking for different people: perhaps steady friends in the place of party people, a partner who is focused on family as well as fun times.

I recently experienced what it is like for one of your most important friendships to break apart. This was someone I had known for years and shared the strongest kind of bond with. We’d sit around all day together, playing guitar and laughing until we almost peed ourselves. It was the easiest, most joyous friendship I have known. But our lives have diverged. Perhaps our careers have progressed at a different pace. The covalence that once so instinctively joined us faded, to be replaced by the sense that my friend needed something more from me, something I wasn’t able to give. In a situation like this, it often feels as though the other person’s weak force is taking over, denaturing some part of their personality or happiness, and threatening to take you down with it. You have to work out whether you are able – through sharing or donating electrons – to help that person re-complete themselves. But it isn’t always possible. Sometimes either the magnitude or frequency of their electronic demand is too great, unsustainable for a healthy friendship. You shouldn’t beat yourself up about it. Humans may be wired to connect, but there is a limit to how much we can offer other people without eroding the strong force that protects our own personality, needs and identity.

When you break up with a partner or close friend, the natural response (after having a good cry, obviously) is to blame yourself. You wonder what you did wrong and what you might have done differently. Bonds can help us reach a more balanced perspective, understanding that there are some evolutions no connection can withstand, and some bonds that were simply never meant to last, even if they played an essential role in your evolution to this point. Perhaps the most valuable thing is to know that seeing bonds break doesn’t have to break us. In chemistry, by definition, a change in bonding or atomic identity is not just the end of one state, but the beginning of another: creating the space for new bonding potential. The same is true for us as humans. It might take a cup of warm milk to reset us and give us comfort after a relationship has broken down. But however many bonds we see come apart, we will always retain one of our most human abilities: to connect afresh, find new friends and love again. Our outer shell is ready to give, or share, its next electron.

The chemical bonds I have talked about here can form in a matter of nanoseconds, a time frame beyond our perception. Human connection can be pretty immediate itself, although we have to be mindful of the difference between these affinities (single interactions) and the biological concept of avidity – the connection created by the agglomeration of all those affinities over time. It is avidity that really connects people in a meaningful way, twisting two lives together through a web of shared experiences, interests, values and ambitions. Avidity of this kind only happens when two people can co-evolve, strengthening and deepening that initial bond so that we don’t strain an initial covalence or magnetic attraction beyond its breaking point.

Nurturing these bonds is something we do instinctively. We will all spend time thinking about how to look after our friends, family and partner: finding the right words to support them at a difficult time, being there to celebrate their successes, even thinking what to cook for them or buy for their birthday. And, at the same time, we obsess over the arguments, mishaps and disagreements. Was it them or us?

Understanding our relationships through the lens of chemical bonds and fundamental forces allows us to see these questions in a new light. With this new perspective, we can better understand human connection, the factors that bring us together and those which force us apart. It helps us to comprehend the force we exert on others, and they on us – and whether that is a beneficial equilibrium or a harmful power imbalance. For me, it is about working out how to approach new relationships, and being able to reflect on those that have gone wrong for whatever reason, without instinctively resorting to blaming myself. Sometimes it’s no one’s fault. The bond breaks because of forces beyond our control. There is always that one tortellino that bursts in the boiling water.

Thinking about bonds allows us to reassess individual relationships and also to think in overall terms. These different kinds of connection nurture us in various ways: covalencies are about the steady, supportive relationships that give us comfort and reassurance; ionic bonds are where we find excitement, passion and often love. One is the river running steadily through our life, a bond that may ebb and flow, or change course, but which never runs dry. Another is the firework that lights up the night sky, thrilling us with its energy and possibility. We need both for different reasons, in a proportion that suits our personalities and life needs at any given time.

Just like the atoms that make us, we are constantly forming new connections, pursuing our fundamental human urges for belonging and stability. Some of those relationships will be fleeting, others lasting. Some will make us, and others will feel as though they are about to tear us apart. No one can ever be entirely dispassionate, objective, or dare I say scientific, about how they form new relationships. But chemistry can give us a new outlook and a fresh perspective: one that provides the confidence to make, break and sometimes re-make the connections that define us.