The real difficulty is with the vast wealth and power

in the hands of the few and the unscrupulous

who represent or control capital.

Hundreds of laws of Congress and the state

legislatures

are in the interest of these men

and against the interests of workingmen.

This is a government of the people, by the people,

and for the people no longer.

It is a government of corporations,

by corporations, and for corporations.

— Rutherford B. Haysx

1

THAT OCTOBER, following our meeting with the President, we rabble rousers, intent on protecting a forest we deemed to be sacred, became even more nuts. We had no choice but to continue to pressure the university and this would surely involve risk. Two unexpected revelations shifted our campaign into high gear. The first I gathered in my interview with President Redlaw almost three decades ago. For the second, fortunately a hard copy survived.

Helen Flintwinch set down her phone and stared blankly at her closed office door. It was seven-thirty on the Friday morning of the worst weekend of fall semester, a weekend when every staff person, every police officer, every executive of Gilligan University of Ohio would be on high alert to prevent Halloween shenanigans from getting out of hand. But what had just been transmitted by her colleague, Grace Battersby, the Vice-President for University Advancement, had nothing to do with Halloween, and it at once answered questions that had puzzled her (and us) and raised countless others.

The provost picked up the phone and caught President Redlaw on his way to his Lake Erie cottage for what he described as a well-earned breather. Not great timing, she told him, for the sixth year in a row.

“Go ahead, I’m on speaker phone,” he cheerily assured her.

“Guess who just called me with news I believe you may already know?”

The president, driving along the freeway, smirked to himself. He knew the correct answer, but acting the rascal on this getaway morning, he decided to goad his provost a few miles more. “Haven’t a clue, Helen.”

“Well, it’s one of your vice-presidents and what I heard stumped me. As I’m minding the store in your absence this weekend, I have little time to delve into matters not relating to Halloween.”

“Vice-President, eh?” He ignored her jab. “Was it Harry Phillips complaining about the boilers again?”

“Okay, Mitch, cut the crap. I’m not in the mood for what substitutes as humor this morning. What am I supposed to do with Tulkinghorn’s Chair?”

“Oh that.”

“Yeah, that. Who in hell is behind Larnaca Venture Capital? And why have they donated twelve million toward a Chair in petroleum and innovative fossil fuel sciences? What does that euphemism imply? And how do they know Dr. Truman Tulkinghorn, whom they decree to be the first holder of this Chair?”

The President cut in. “Hang on a minute, Helen. Let me take another call.”

She took this to be a deliberate extension of his pretense. But the call was real. After five long minutes, during which she could do nothing but stew, he returned with what sounded like a genuine apology.

“Lottie there,” he said referring to the Director of Legal Affairs. “She’s been in conversation with Payne Orlick. Payne’s thrilled about the donation because two million dollars are slated toward improvement of lab facilities and equipment in his college. He says having to live with Tulkinghorn is a small price to pay for those upgrades and it will bring notoriety to the School of Conservation and Natural Resource Development as a center dedicated to making shale oil and gas more environmentally acceptable. Lottie says she can find no legal stumbling blocks to the appointment, not even in the faculty handbook. Donors have called the shots for most of our named Chairs. And to answer your question about Larnaca Venture Capital, I honestly know nothing of them. Lottie’s making sure they are legitimate.”

“Shit!” swore the provost. “There’s no way shale oil and gas will ever be environmentally acceptable to those protesters and that man Tulkinghorn is my nemesis. Half his faculty detest him.” Good grief! The provost just put forward our main objection to fracking beneath the forest and our suspicions about Dr. T..

“These are lean times, Helen.”

“Bottom line, then? Big bucks trump reason and Tulkinghorn gets last laugh. For what it’s worth, my recommendation is to reject this gift along with its strings. This firm, or whatever it is, has no connection to Gilligan.”

“While I cannot ignore your recommendation, Helen, you know full-well that my job is to raise money for this university. Put yourself in my shoes. I mean, this is as easy a take as I’ve ever seen. We run with it. And we don’t make a big thing out of checking the teeth of this gift horse. Unless Lottie puts up red flags, this is a done deal.”

“Well, I hope I’ll be out of here long before this horse gets caught fixing a race.”

“Me too. Bye Helen.”

Mitchell Redlaw switched off his phone and inserted a disc into the player on his dashboard. He loved this old technology, did not own an iPod or MP3, had hardly heard of them. Old technology. New technology: all irrelevant now except for the typewriter beneath my fingers. For a jock, the president’s musical preferences surprised me. On that day, his choice was St. Martin-in-the-Field’s rendition of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos. As if in the concert hall, he tapped his hands on the wheel and occasionally swirled his right hand in arcs directing the orchestra. Off on his annual autumn escape, unplugged and relaxed, he told me his spirits soared.

2

“Yeen talmbout shit?” José asked Astrid.

“No way,” she replied, shaking her head vigorously, tangling the wire for her earbuds into her thicket of dreads. She fished out the offending wire. “My colleagues and I are one-hundred percent certain of the source, just not the proportion of the income of this spider web empire. And the revenue-generating activities au courant all point to one of his enterprises as well.”

“Au courant. That mean now?” José inquired, straight-faced.

“Si.”

The rest of us seemed too dazed to chuckle or comment, as if Astrid had finally revealed unequivocal evidence for the existence of both Sasquatch and aliens in Area 51. Her revelations raised thorny decisions we could never have imagined when, three weeks earlier, we chased Dr. Tulkinghorn around southern Ohio.

Nick finally came alive. “Astrid, I don’t get why you and your hacker buddies have such confidence when, by all rights, if what you say is true, the NSA, the FBI, the CIA, and Europol ought to have entrapped the man long ago and rendered him off to some black site in Slovakia.”

“We’re smarter than they are, as Kevin Mitnick and Alberto Gonzalez have resoundingly shown.”

“Are those guys in the hacking hall of fame or something?”

“Yeah, and now they’re joined by Edward Snowden and dozens, if not hundreds of unsung heroes, many of them brassy women like me.”

“Hmm”, said Nick, tap dancing around her description of herself. “Okay, what do we do with this?”

Lara offered a cautionary note. “We’ve got to be very careful here.”

“No shit!” rejoined Astrid without humor. “If not, my ass is grass.”

“Don’t want that,” offered José with what could have been taken as snarky humor. It wasn’t. I noticed that José had developed heartfelt respect for his Canadian classmate, the high priestess of the brainies.

Katherine then calmly attempted to shed more light on our predicament. “Right,” she began. “Based on Astrid’s research, we know that Morse is connected to, if not pulling the strings for a far-flung thing called Gruppo Crogiolo. We’ve heard that his dealings rank his assets right up there with David Koch.”

“Koch is a mastadonic stretch,” interrupted Astrid, frowning. “Actually, by orders of magnitude.”

Who else could spin out sentences like these?

“Okay I grant you that,” replied Katherine. “My point is that his wealth is phenomenally more than one would derive from a smallish firm mining coal and exploring for oil and gas.”

“That is for sure,” agreed Astrid.

Katherine pressed on. “We know nothing of partners, but you believe he must have them. And now you tell us that this expanding organism was built largely on trading in Iranian oil during the long embargo!”

“This is what scares me more than anything,” Sean interjected. “If Morse has been doing this right under the nose of the State and Justice Departments, I mean, if this is so and we reveal it to the press, we’ll be dragged through unbelievable scrutiny, and, yeah, Nick, we’ll probably be rendered not to one of those black sites but instead to a sausage factory.”

“Sean!” Astrid exclaimed. “Aren’t you the guy who got queasy in the human anatomy lab? How could you even imagine a rendition so gross?”

“You can’t imagine the depravity of my imagination,” Sean replied. “But what about Morse’s blatancy. Is this man totally above the law?”

“Appears so,” Astrid answered.

“Okay, if I may continue,” Katherine said. “Astrid also revealed that Morse’s organization is shifting to or is being augmented by hacking into international banks. How incredible is that? Then, José and Nick informed us that over the years Morse has dodged federal prosecution for violations that have led to deaths, and injuries in his mines and that his Gilligan grudge may have its origins in a failed sophomore class in geology followed by a dispute with the professor that made it into The Press in May 1967.”

“Yeah, and to rub salt in his wound, the grievance was denied by the university,” added Nick.

“Finally,” Katherine said, “we read on Gilligan’s website this morning that Larnaca Venture Capital, a shale oil and gas investment firm, will fund a chair in the School of Conservation and Natural Resource Development. Isn’t Larnaca the place where Gruppo Crogiolo is registered?”

“It is,” confirmed Astrid. “But I could find no connection between Larnaca Venture Capital and Gruppo Crogiolo.”

“Dr. Tulkinghorn was not mentioned in the announcement,” Katherine continued. “But he’s the only petro prof in our school, so this must be the outcome of a deal cut between Tulkinghorn and Morse in Henry Falls.”

Our group shut down again, overwhelmed by the facts and speculations Katherine had just spun out: a story more the plot of a Le Carré thriller than something unfolding in the backwaters of southern Ohio. The room began to shrink. The emerging picture was simply staggering. Should Morse discover what we knew about him, his wrath was at least as awful a prospect as that of the NSA. Mulling over this, I gazed through the folds of the sheer curtains covering the windows of the meeting room in the Josiah Brownlow Library: pale light spilling across the table where my twelve conspirators sat, bewildered and frightened. It was late afternoon on Friday of the Halloween weekend. A warm, hazy late autumn day waned toward a mini-skirt-sheer-blouse kind of evening to launch the festivities that would propel uptown Argolis into a southern Ohio version of Bourbon Street at Mardi Gras.

Rubbing his neck and rolling his head round and round, Nick said, “How to make best use of our intelligence is going to be difficult. If we’re too vague, we won’t be taken seriously. If we’re too specific, we’ll have the law seizing us and our computers before you can say au courant, especially if people in high places also know what we know — the governor, for example. Yeah, we probably would be sequestered for years in some dark prison in Bratislava.”

“Man, you’ve got Slovakia on the brain today,” Astrid said. “But that’s a better outcome than a sausage factory.”

“Leave it to Astrid to know where Bratislava is,” chided José. “And Nick, aren’t you bordering on paranoia here?”

“Okay, some paranoia, yeah. But, bro, this predicament is one tricky mine field.”

“Mine field, sausage factory, what next?” inquired Sean without the faintest hint of irony.

“Les énigmes!” exclaimed Em out of nowhere.

“What?” asked Zachary.

“A mine field of enigmas,” explained Nick.

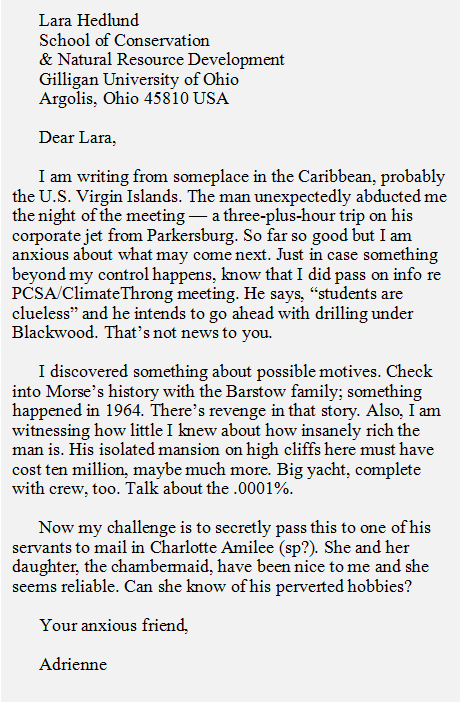

“And there are others, I hate to tell you,” added Lara who had patiently waited to reveal the letter she found in her mailbox that morning. “Remember that I told you that I believed I had recruited Adrienne to implant some misinformation during her next liaison with Morse? Well, I received a letter from her this morning, postmarked October 17th from Charlotte Amalie, U.S. Virgin Islands; that is, two days after we saw her at that unruly meeting eight days ago. Let me read it to you.”

After she had finished, Zachary blurted, “Holy fuck! Was Adrienne banging that old man for intelligence?”

“Yeah, if one were to put it crudely,” Lara responded.

“It seems like Adrienne directed us to look further into Morse’s history and motivations,” Sean calmly observed. “Perhaps that would yield something important.”

“I agree,” Lara replied. “So, I phoned Malcolm Barstow. You remember him?”

“Yeah, the caretaker of Blackwood,” I offered.

“Right. Malcolm and I have had many cups of coffee in his kitchen. Over the years he’s been kind to me. He once told me he did not care for Morse. He said that Morse is not a nice person. In my call this morning, I asked him point-blank what happened in 1964. With a great deal of hesitation and reluctance, Malcolm revealed that Morse had been sweet on his younger sister, Belinda, but that another ‘suitor’, his word, ‘came into the picture’, again, his words, and Belinda and that other guy got married, leaving Morse jilted. That was the long and short of it. Malcolm believes Morse still holds a grudge against the family, which now comprises only him and his daughter and granddaughter in San Diego.”

“Is Belinda still alive?” asked Sean.

“No. She died a few years ago of complications from open heart surgery.”

“Too bad,” said Katherine. “Okay, this, together with his failed course, could explain his obsession with Blackwood. It’s a human-interest aspect of the story, let’s say, not something legal, right?”

“Yes, that’s so,” agreed Lara. “But I need to tell you something else. I’ve had a chilling premonition since Adrienne and I talked outside The Jenny. I got the sense that night she might be over her head with Morse. She said something hideous was driving the man; that he was a serious head case. I asked if she were in danger. She told me she could handle him.”

“Has she been in touch since the seventeenth?” asked Katherine.

“No, and that’s what worries me, although she’s never been a reliable communicator.”

“Have you tried contacting somebody who knows her?”

“I would. But I have no clue about her family or friends. I don’t even know where she grew up.”

Astrid quietly hopped on Google and was scurrying from site to site, opening and arraying them one on top of another. “Ah ha!” she shrieked. “Lara, check this out.” She made haste around the table, laptop in hand, to show Lara the Virgin Islands Police Department blotter.

October 21: 09:16 — MISSING PERSON

A missing person, Ms. A. Foster, was reported to the desk sergeant by Mr. J. Morse, of Bartley Bay Road. Ms. Foster had been a guest of Mr. Morse. Detective Wesley Rollins assigned to case.

“Was Adrienne’s last name Foster?” Astrid asked.

“Yes”, replied Lara as she buried her face in both hands.

3

The room fell silent. Katherine wrapped her arm around Lara’s shoulders. Lara emitted short breaths, almost inaudibly. I found a tissue and passed it across. Frank tried to diffuse the tension in a room that felt like a tomb. “Are we in some kind of Masterpiece Mystery episode?” he asked. Few around the table could make sense of that, typical of Frank’s frames of reference.

José smirked and asked. “What galaxy gave birth to you, Frank?”

“Check it out. Great BBC mystery dramas, every Sunday night.”

“Sunday nights, every night in fact, I’m rehearsing,” José said.

“Back to basics,” Nick cut in, still gazing at Katherine and Lara, perplexed by the open-heartedness of the women, a state of being foreign to him and driven by motivations without a trace in himself. “Okay,” he sputtered, “we’ve got powerful information here and because the permits for drilling have been issued, it’s time to deploy it. Astrid, would it be better to focus on the banking hacks, thus avoiding Iran, international boycotts, shadowy shell games with oil revenues, and organized crime?”

“I doubt it,” she replied.

“Why?” asked Nick.

“For one thing, the pathways of hacking into accounts in big banks are serpentine and difficult to justify. Secondly, my expert colleagues, who may understand how that works, are hesitant to speak about it.”

“They’re into this kind of hacking, then?”

“I wouldn’t know.”

“Why then do you suspect that Gruppo Crogiolo is into this?”

“I can’t answer that.”

“Because you know and it’s a trade secret or because you just do not know?”

“Both, actually. I wasn’t informed of the way my colleagues arrived at that conclusion. I have to assume it is proprietary information.”

“So, what’s the use of this intelligence if we can’t use it?”

“Good question,” Astrid pursed her lips and nodded repeatedly, her left hand wrapped around her chin. The naïve glee of her initial revelations three weeks earlier had gradually dissipated. Now the current series of reality checks mired us in a cruel paradox: at hand, evidence of grievous wrongdoing that at the same time would not stand up in court and, in any event, could not indict Morse in time to save Blackwood. Further, if revealed, such evidence could dispatch Astrid and probably everyone else straight to jail.

Taking in Astrid’s gloomy demeanor, the rest of us lapsed again into confusion. After some anxious moments, Em said, “I am not expert in this stuff, but I think our best choice is to contact the detective in Virgin Islands.”

“I agree,” said Astrid. “If I had another few days, I think I could find a way to scare the shit out of Morse. But now, he can deny everything and, though I am quite certain of the pieces of his empire, I’m not to the point where I can penetrate it.”

“Let’s call the detective now,” suggested Julianna, the woman of action who would oversee the occupation of Centennial Quad in just a few hours.

“Let me try,” offered Lara.

Lara left the room.

Fifteen minutes later she returned. “I managed to catch Detective Rollins just as he was leaving the office,” she said. “He took my particulars and asked a bunch of questions. I read the letter to him and informed him that I had reason to believe Adrienne had been in danger. The letter seemed to justify that, he said. He asked what ‘perverse hobbies’ in the letter meant. I told him that I could not answer that, but that I knew that Morse had paid for her services in the past. ‘Is she a professional prostitute?’ he asked. I told him not that I know of.”

“What about Adrienne?” Katherine asked.

“He said no trace whatsoever.”

“Has he interviewed Morse?”

“Yes. The investigation is continuing but Morse has apparently left the island and so far, Rollins had been unable to contact him. I snapped a photo of the letter and sent it to his phone.”

“Morse is on the run,” José said.

“Probably,” replied Lara. “And if so, one is tempted to assume guilt. Oh God …” she whispered.

“That could be too reductionist a solution,” Zachary suggested. “Maybe he’s gone to The Caymans to move some money or is in Europe or North Dakota, doing what he does.”

“That too is possible,” admitted Katherine. “What next?”

“I have something, Katherine,” I said. “A couple of weeks ago, the day of the president’s press conference in fact, Dr. Tulkinghorn came into the office with an express mail package. I paid little attention to it but later I noted the empty envelope in the recycling bin. Like Sydney Fitzpatrick, I carefully inspected it and wrote down the return address.”

“Sydney Fitzpatrick?” Katherine asked.

“My favorite FBI special agent. Just read The Bone Chamber.xi You’ll become hooked.”

“What was the address and why do you think this is important?”

I read from my journal. “Well, it was from an Ibrahim al-Nazer at Amerabic Corporation in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. When I brought Dr. T. coffee that morning, I found him intensely reading the document.”

“It may just be academic correspondence or something to do with Tulkinghorn’s consulting,” argued Zachary.

“Is there any way you could find out?” Nick asked.

“Let me try.” I excused myself.

“Ibrahim al-Nazer,” interjected Astrid, reading from her laptop. “Former Minister of Petroleum for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Presently, assistant to the CEO of Amerabic Petroleum, Ltd., the world’s fourth largest oil company, wholly owned by the Kingdom.”

Nick asked, “Katherine, have you made that call to President Redlaw?”

“No, I wanted to wait until after this meeting.”

“I suggest you make the call soon. Tell him our plans for the weekend: the march and rally tonight, the occupation of Centennial Quad, our presence at the Halloween block party, and the teach-in Monday. Tell him also that the police in the Virgin Islands are investigating the disappearance of a friend of ours who was in the company of Jasper Morse on October 17th, and provide the name and phone contact of the detective.”

“So, we’re holding back on Gruppo Crogiolo?” asked Astrid.

“That would be my recommendation,” Katherine replied. “At least until you achieve the level of penetration you mentioned.”

“Should I keep working on that?”

“Absolutely. That’s just my opinion.”

I returned to the room, bringing proceedings to a halt.

“Anything?” Nick inquired.

“Not quite, but soon maybe.”

When my phone rang, people came to attention. I left the room again.

4

Breaking away from my friends, I hurled myself toward McWhorter. It was after five. I hated to be causing Greta to stay late. When I got to the CNRD office, I found it locked. I tapped gently on the door. Greta cautiously opened it. The office was dark except for a desk lamp illuminating a small circle at the work-study carrel. Greta led me there.

“Here is the document from the Saudi oil executive. It was in a locked drawer in his desk. Read it here. If you want to take notes, it’s okay. I don’t dare make a copy. When you’re finished, I’ll return it. Before you touch it, put on these gloves.”

“You too?” I said looking at Greta’s hands.

“We can’t be too careful.”

I began reading the single-spaced pages. As I read, what came out of my mouth was the occasional “Ewww,” “Ohhh,” and “Yuk”. In my diary, I jotted a few phrases with arrows connecting one to another.

“This totally grosses me out. Until one of my roommates told me about BDSM last year, I was clueless. She forced me to read Fifty Shades of Grey. It made me sick, not horny. In Morse’s operation the women appear to have been sex slaves.”

“It’s not for the faint of heart. Nor for women with a strong sense of self, like you.”

“Strong sense of self, Greta? Not exactly. But I’m strong enough to be totally disgusted by sex trafficking, bondage, and assault. What I don’t understand is: Isn’t Saudi Arabia one of the most conservative and repressive countries in the world? So, how do you suppose Morse got away with this? How did he escape imprisonment or beheading or something?”

“There’s a probable explanation, on the third page. It says something about the princes and the syndicate.”

“Who are the princes? Is the syndicate Morse’s whore house?”

“I assume the princes are male members of the royal family. And yes, I think the syndicate is a euphemism for the concubinary or whatever one may call it. In any event, this was probably the information used to blackmail Morse.”

A knock on the door.

“Quick”, Greta commanded. “Remove your gloves. Boot up the computer. Pretend to be working. I’ll hide the document.” After some moments, she opened the door a crack.

A voice in the hallway. “Oh, hello Greta,” someone whispered. “Hannah asked me to meet her here.”

Katherine came into the darkened office. We greeted one another.

Greta showed her the document. When Katherine had read it, dumbstruck, all she could say was, “How utterly hideous.”

5

Stefan’s Journal

Nuclear Codes

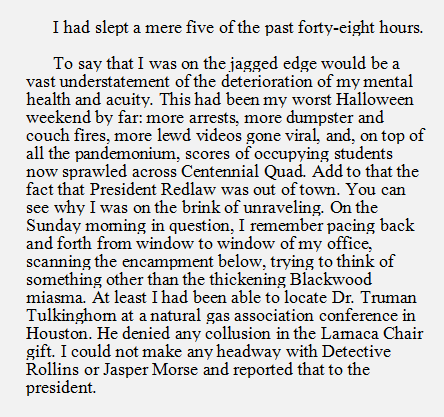

Stretched out on the couch, I am feeling bone-tired.

Friday evening, home alone. The throaty vibes of jazz pianist and singer Diana Krall float across my little apartment. She wails, There ain’t no sweet man that’s worth the salt of my tears. Feeling a little blue and a lot drowsy, I half-heartedly read a book review in last Sunday’s New York Times. The book, Good-bye the Academy, argues that colleges and universities, as specific places people gather to learn, will soon be history. In future, all but an elite few will be learning via online university programs and courses open to the masses. The days of professors and students in traditional mortar and brick buildings and classrooms are over according to this author, an educational theorist with a think tank in Palo Alto. God, if this woman’s predictions were to happen, here’s just one more piece of the dystopian future. Dependence on “the cloud”, an assumption of this book, is one hell of a risky business plan for universities of the future. But, of course, that never enters her argument. Feeling out of sorts, I flip the newspaper onto the coffee table and doze off.

My phone trills.

“Stefan, Katherine here. I’m about to make the call and I wanted to check in quickly before I do.”

“The call?” I’m half-asleep.

“Yes, to Redlaw.”

I cannot come up with words.

“Oh, sorry,” she apologizes. “Did I catch you at a bad time?”

“No, no. It’s okay. I had just dozed off. How can I help?”

“I’m reluctant to share details on this channel, if you know what I mean.”

“I get it. Yeah.”

“Look, Stefan, could you possibly come here? I need to run some things by you before calling the man.”

“Where’s here?”

“My apartment.”

“That would be more than a bit risky, Katherine. Any roommates or nosey neighbors around?” My mind went back to Burt’s observation that any excuse for Katherine and me to find each other would serve. Living proof. As ever, I feel the eternal tug of war: the ethics of my profession versus my obsession with a woman who happens to be my student. What to do? Every time I am with her, I feel a direct current passing between us, a sensation I’m pretty sure she wouldn’t deny. Even if we don’t touch, don’t speak, we can feel the electrons snapping across space, accelerating our heartbeats.

“No, no nosey neighbors. No roommates either,” Katherine responds without hesitation. With heart-cheering brightness, she asserts, “Everybody around here seems to have gone uptown. The sun has set. It’s getting dark. You’ll be fine.”

“Okay, I’ll be there in fifteen minutes.” My lethargy has scampered away on the heels of virtue.

I lean my bicycle at the railing and ring her doorbell. Katherine calls down, “Door's open. Come on up.” At the top of the stairs I find her crossing the small kitchen toward the entryway. If in our last encounter in class she was a bit lugubrious, there is none of it now. She’s aglow to see me but then she curiously stops short and says, “Here, let me take your jacket. Have a seat. Can I get you something to drink — a beer?”

“Sure.” I fold myself onto a kitchen chair while sizing up the shabby student apartment with endearing touches of Katherine: a colorful bowl, yellow damask curtains, some framed Italian scenes on the kitchen wall above the table, candles everywhere, photos of smiling people on the fridge. I wonder about her mix of hospitality and brusqueness. I tell her that I was unable to find out why Dr. Tulkinghorn had been balmy the other afternoon.

From the refrigerator, she calls back, “No matter. We already know.”

She comes across with two beers. We tap our bottles, briefly locking eyes. She says, “Thanks again for coming on short notice. It seems like d-day and h-hour for us, Stefan. The steering committee believes that because of the permits, we’re on a short leash trying to slow down or stop drilling at Blackwood. We’ve got protests of various sorts and an occupation of Centennial Quad planned from tonight through Monday. One would think that waiting until Monday to call Redlaw, when the impact of these protests will be better known, might make more sense. But there are two new developments that have accelerated things.”

“New developments?”

“Yes. Prepare yourself.” She summarizes the news about Morse’s possible involvement in Adrienne’s disappearance and of the likelihood that Dr. Tulkinghorn had blackmailed Jasper Morse in return for the Larnaca Chair.

“Ah, so that’s why Tulkinghorn was giddy the other day.”

“Yes, apparently, though he has not been specifically named. In any event, this is the information I am meant to convey to the president.”

I take a swig of beer and shake my head. I spurt a response emanating from my boyhood. “Them're some wicked cawkar tales, Katherine.”

“What? You think I made all that up?” I note the off-kilter smile on her lips. In spite of herself, she breaks up. I smile, relieved that the awkwardness of my being here, the stilted atmosphere, have evaporated.

Just as quickly, Katherine’s eyes become dark. “God, Stefan, I cannot help but think that Adrienne is either in serious jeopardy or dead.” She shakes her head, turns briefly away, brushes a tear from her eye. “Shit! Pardon my language but Morse has become the personification of evil in my mind and now it’s not just about Blackwood. It’s all so obviously simplistic, so juvenile, like a young adult mystery or something: this brute of an antagonist.”

I look back across the table at her face, shadowed in sorrow, her lips trembling. Katherine had never come close to swearing in my presence. I feel the surge again: my intoxication with her amalgam of grit and tender heartedness. I try to calm my racing heart. “Maybe it’s not so simplistic. Do you think Morse is a murderer?”

“He was apparently the last person to have seen Adrienne. Who knows?”

“What about all the evidence on his global empire?”

“Because of its sensitivity and some gaps in our knowledge as well as the risk of bringing federal agencies or the governor’s office down on us, we have decided to hold it back, at least temporarily. What do you think? Is this the right time? Is the president likely to take us seriously?”

“I’ve never met or even seen the man.” I regret my brusqueness and soften my tone. “Aren’t you a better judge than I of how he’ll respond?”

“I suppose I am. And I do trust him. Again, that may be naïve. I’ve got absolutely no points of reference. But tactically, do we want him to have this information just as we’re launching what we hope will be game-changing protests and the occupation?”

“Game-changing?”

“Well, we are Facebooking and Tweeting with hundreds of followers. Go to #blackwoodforever. You’ll see. “

“Hmm, Katherine. Me following something on Twitter is as likely as me dressing up as Jasper Morse on Federal Street tomorrow night.”

“You are one dedicated Luddite, aren’t you?”

“I choose to stay away from social media but, unlike Ned Ludd, I’ll not be wrecking their machinery.”

“Good. We need all those geeky connections.”

“When do you plan to release information about Morse to the media?”

Katherine pauses a moment, seeming to parse her words carefully. “After our steering committee meeting broke up this afternoon, Lara came to me. She is understandably the most frazzled and has the most to lose in Blackwood. She doesn’t want Professor Shesky to know of her involvement. By rights, she should be running the show, not me. In any event, she advised, how shall I say? That I promise the president that we will refrain from talking to the press about what we know for, say, twenty-four hours to allow him and his administration time to check our facts. She thinks I should issue that as an ultimatum.”

“By gory, things are sure coming to a head.”

“The drama is almost too much to absorb, Stefan. I hope I’m up to the task,” Katherine abruptly halts and gazes vacantly across her kitchen into the adjacent sitting room, now dark as the moonless night, as if she is drowning in self-doubt, her precarious post as coordinator of an unpredictable and unruly band. Just as abruptly she chugs the rest of her beer, slams the bottle on the table. “Alright, time to call the man,” she declares.

She dials and waits, her expression revealing nothing but perplexity. She cancels the call. “Huh? It went right to voice mail. He told me to call any time, day or night, said he would respond. Okay, if he doesn’t answer, I’ll have to leave a message.”

She makes the call, ending her message with, “We hope you will treat this as urgent, sir.” She looks at me with raised eyebrows, a brief shake of her head, her eyes betraying the confidence of a few moments past.

I consider those beguiling eyes and acknowledge her frustration. “To change the subject, are you hungry?”

We sit side-by-side on her tattered couch, munching Landslide Pizza, chatting about grad school and the readings for our next class, assuming, she says half-jokingly, that the whole caboodle doesn’t topple by Tuesday. She says, slyly, that not many students can boast of a professor so close at hand to tutor them. I agree that this is so. Like a tongue-tied fifteen-year-old, I am stumped about where to go next. Her beauty is subtle and intriguing, eyes that draw me toward her soul, a willowy body that moves gracefully through its days. And here on this night of consequence, unable to say something memorable, I nonetheless bask in her warmth.

When she carries the remnants of our impromptu dinner to the kitchen, I rise and tell her I should leave her to the evening’s rabble rousing.

She grins at my locution and says, “Yes, and you’d best slip silently into the night.”

“I had no idea that my first venture to your place would be the night you’d be carrying the nuclear codes.”

“Kind of puts an edge on things, wouldn’t you say?”

“It does. But, Katherine, this too shall pass. Rumi tells us: Don’t grieve. Anything you lose comes round in another form.”

“Here’s the form I’ll be dreaming about,” she replies, misty eyed. She melts into my arms. We stand there entwined for some moments, perilous and wrought with longing. I step back.

As I head toward the door, she says, “You and Rumi, double-teaming me. What am I supposed to do?”

“Just be,” I tell her.

6

As I reflect on the next few days of our story, my head spins. So much transpired in such a short time and at such a pace, I fear that I will but lamely capture our accomplishment, our exhilaration, and ultimately our fears about the outcomes of our efforts to alter the course of history. I am indebted to Dr. Helen Flintwinch, Mayor Vernon Alexander, and Chief Annie Barnhart for their viewpoints on our challenge to their hegemony and for their quite reasonable, but ultimately unrealistic belief that our movement could be contained or at least detained. Since I spent zero minutes at their command post or in their offices, I asked President Redlaw to confirm their accounts. All he said was, “Go with them, Hannah.”

We quite deliberately chose Halloween weekend to launch our occupation. What was about to happen in uptown Argolis on that weekend would require more overtime police hours than the rest of the year combined. Festivities would comprise virtually anything you could imagine in a party lasting two nights and one afternoon in a four-by-four block district with upwards of 30,000 mostly young, and for the duration, at least moderately drunk and stoned partiers. Us. Despite the dead-serious police presence with backups of riot-equipped and equestrian contingents, by 3:00 AM Sunday morning, more than two-hundred celebrants would have been arrested on charges ranging from drunk and disorderly, to indecent exposure, to assault with a deadly weapon, and, of course, resisting arrest.

After years of street takeovers and clashes between police and partiers, in the mid-nineties, Halloween became an official town-gown-sponsored event, an evolution unimaginable in the rowdy eighties when both the city and the university unsuccessfully tried to shut it down. Halloween weekend was now elaborately orchestrated and heavily patrolled. Yet it still possessed unstoppable madness. Halloween in Argolis had thus held, for over thirty years, a reputation as the best October block party in Ohio. To the administration of Gilligan University Ohio and to the city officials of Argolis, Halloween was nothing but one long pain in the derrière. To make matters worse, from their viewpoint, the university’s ranking as one of the nation’s top party schools rose dramatically after each Halloween fiasco. (Although few student partiers explicitly aimed to enhance or sustain this rank, neither would any of us have lamented it.)

So, on Friday evening, uptown streets would be closed to traffic and given over, first, to children and their parents with a costume competition, children’s activities sponsored by community and campus organizations, clowns, a parade of massive puppets, and the outdoor presentation of Peter and the Wolf at the amphitheater on Southwell Quad. By nine, after the streets would empty of kids, they would begin to pulse with so-called adults; many from other campuses, roving from bar to bar, hitting on each other, occasionally enjoining in brawls, many bearing IDs of great invention, all gorging themselves on food served up by food carts and the multitude of restaurants up and down Federal Street, almost all planning to get wasted at the most incredible party they would hardly remember.

On Saturday afternoon, uptown streets would close to traffic again. If trends from past years held, the crowd Saturday night would be the largest. The main events Saturday would rock three stages with eighteen bands performing almost continuously. By about nine o'clock, droves would pour onto the streets in costume: pregnant nuns cavorting with swarthy pirates or drunken priests, dominatrix spankies with febrile nearly naked slave-men, blue men with PVC pipes, angels and devils tempting staggering prophets, monks au naturel beneath their robes (flashing from time to time), happy Buddhas, Arab Sheiks, Catholic Priests with Jack Daniels bottles, party girls in skimpy lingerie, and the latest animation characters (this year, Sponge Pants Bob bobbing through the crowd along with monsters from Monster University and the Croods).

Infused by a colossal plunge in the collective intelligence of thousands of our classmates, our brains awash in gonadal hormones, alcohol, and cannabinoids , by Saturday night around midnight, a tipping point would be reached when good clean fun would flip over to Sodom and Gomorrah and videos of young bodies copulating on steps of churches would go viral. Even before midnight, in the windows of second and third floor apartments and on flimsy balconies overlooking Federal Street, women (and so-called men) would be coaxed by the masses below to bare key parts of their youthful anatomies to us gawking adolescents down on the street, some of whom would respond in kind. As a prude from Ashtabula, when I witnessed this lascivious phase last Halloween, I confess to arousal rather than revulsion.

Responsibility for this looming event fell squarely on the shoulders of Provost Helen Flintwinch, Campus Police Chief Annie Barnhill, and Argolis Mayor Vernon Alexander. It was Friday night. All three were perched in the offices of Dodson, Knapp, Barnacle, and Fogg, Attorneys at Law, on the third floor of the Bundy Building at the corner of Federal and Jefferson, the Halloween command center. The hour was 9:00 PM.

Chief Barnhill idly gazed down at the sparse crowd of students slowly displacing children and their parents. She turned to the mayor and asked, “Any predictions?”

“Well, you know, Annie, any expectation I might have will likely be the photonegative of what will actually happen. So, with that in mind, I predict this evening will turn to shit.”

~

I found Katherine at the corner of Spruce and Ohio, the meeting place for the march. We stared aghast at the mass of protestors melting away into the dark. Frank saw us. “Hey guys, how’s this for a turnout? And this does not even include those heading toward Centennial Quad.”

“I’m speechless,” Katherine replied. Astrid, Nick, Em, José, and the others of our Group of Thirteen gathered round. “How did the president respond?” Nick asked.

“No response. My call went straight to his voice mail. I had to leave a message.”

“That sucks.”

“Yes, if he doesn’t get back to me soon, I’m not sure what to do. In less than an hour he’ll have to deal with our occupation of the quad. This is making me crazy.”

Nick said, “Well, Katherine, we’ve got a few hundred folks here anxious to march, so to hell with the president. Let’s get this show on the road.”

Our procession began to weave its way toward the courthouse, trying without success to stay legal and keep to the sidewalks. Compared to the campus protest ten days earlier, we carried more signs and noise makers, including Caribbean steel drums, Tibetan horns, and didgeridoos . At the head, Frank and four of his best friends, dressed as grim reapers wearing skeleton masks, were swinging scythes with signs reading: Blackwood: The End is Near.

“Where'd you come up with those grain slashers?” José called to Frank.

“They’re scythes, man. Folks at the Country Corners Museum out in Mud Flats loaned 'em to us.” Frank swayed to rhythms that might have passed for Trinidadian calypso. José quickly got into the beat moving fluidly along with the crowd. He sidled up to me. I was stomping along like a wooden soldier.

“Hey baby, loosen up! Sway those hips, shake your bootie, bounce those boobs, get your shoulders moving.”

I cracked up. “Hey bro, I’ve got none of those feminine charms, but grab my hand and I’ll follow.” He did and my spirits soared. This night was going to be awesome!

We marched southward on Federal toward campus, crossing Park Street, and stopping finally at the Argolis County Courthouse where Jefferson Street crossed Federal. Waiting for us on the steps of the courthouse was Weston in shiny dress shoes, pressed charcoal gray slacks, and a blue-striped button-down shirt. He had tied a big GREEN ENERGY NOW banner across the columns at the front of the courthouse and had set up a small podium and portable PA system. The drumming and percussion continued. Onlookers gathered to watch. Frank and the other grim reapers climbed the steps and began line dancing to hoots and cheers. They had the crowd in their palms while leading their familiar chants:

NO MORE COAL. NO MORE GAS.

WE WANT ENERGY THA'S GONNA LAST.

NO MORE COAL. NO MORE GAS.

WE WANT ENERGY THA'S GONNA LAST.

GREEN ENERGY! GREEN ENERGY! NOW, NOW, NOW!”

And a sanitized version of the Redlaw reproof:

BLACKWOOD, BLACKWOOD, SACRED SPACE

REDLAW, REDLAW, YOU’RE A DISGRACE

The chants were followed by five student speakers, each more impassioned than the last, the crowd responding enthusiastically to their exhortations. Zachary, the last to speak, worked himself into a sweat, topping off his oration with “This is our generation’s challenge. OUR generation! We are the ones to halt global warming. We are the ones to make the transition to renewable green energy. If we do not make these changes, our children and grandchildren will have no future. WE MUST STOP FRACKING. We must save Blackwood Forest before we plunge over the cliff into oblivion. Blackwood is a metaphor for our times. Save Blackwood, Save Blackwood, Save Blackwood!”

~

Chief Barnhill, Provost Flintwinch, and Mayor Alexander were joined by Argolis Police Chief Dirk Waldecker. Drinking freshly brewed strong coffee, they relaxed in a conference room, munching pumpkin-shaped Halloween cookies with orange icing and chocolate sprinkles. Their light conversation was interrupted by muted sounds coming from across the street, three stories below: the percussion, our chants, our cheers for the grim reapers. The mayor adjusted his hearing aids, stood up and stretched. He steadied himself and zigzagged into the adjacent room facing the street.

“What in hell is this?” he called back to his colleagues.

They rushed to join him at the open windows.

“Oh God,” said Helen Flintwinch. “The Blackwood crowd. Do they have a permit, Vernon?”

“Permit?”

“Yeah, to hold a rally on Federal Street.”

“Dunno. Do they need a permit, Dirk?”

Dirk stroked his chin. The incitements of speakers drifted upward. “I guess since Federal is closed to traffic and they’re not doing anyone harm, we can let them be. Are they the ones who rallied on campus a couple of weeks ago, Helen?”

“Probably.”

“And they were peaceful, right?”

“For the most part, yes. A small altercation caused us to issue a cease and disperse.”

“Altercation?”

“Reputedly one of the vice-presidents was bumped by protestors on her way out of Stiggins.”

As they watched, the grim reaper with the goatee stepped to the podium to lead the crowd in chants, following which the percussion fired back up while he and five other grim reapers danced in syncopation down the steps toward the darkening campus. The mass of protestors followed us along with dozens of partying onlookers curious about what would happen next.

“Looks like they’re headed toward campus, Helen,” Chief Waldecker speculated, his tone flat as a court stenographer. There was a reason he was chief of this backwater town.

“Damn!” The provost looked across to her campus police chief. “Annie, alert your people. Tell them to stay out of sight. As soon as those protestors step on campus, have somebody report back. Where the hell is that scoundrel Redlaw now that we really need him?”

“Hey, yeah, where is he?” repeated the mayor as if he’d just noticed the scoundrel’s absence.

“Off fishing on Lake Erie.”

“What'd I say about the evening turning to shit?” the mayor asked.

“Doesn’t look like a photonegative to me,” Annie Barnhill replied.

~

We protestors banked left on Clayborne and snaked down the street, laterally undulating and sidewinding toward the main portal on the north side of Centennial Quad. Up the steps we slithered into the Quad to the resounding shouts of dozens more supporters hiding at the edges. From the shadows of Weary Hall came masses of occupiers from the east. From the darkness around Chapman Hall converged still dozens more from the west. Our crowd, now numbering three hundred, responded again to the grim reapers’ line dancing moves and chants. Some in the crowd of onlookers began to lend their voices to the hubbub. Frank hushed the crowd, invited the occupiers to set up their village, and returned, clapping to the pulsating beat of the frenzied mass.

As the village took shape under the direction of Julianna Ferguson, percussion ceased. Nick, holding a bullhorn and a large flag bearing a spreading oak and the hashtag #blackwood forever on a regimental stanchion, christened the Quad Village. He staked the flag at the center of the quad and announced: “I hereby declare that we the students of Gilligan University of Ohio, defenders of Blackwood Forest and ardent haters of fracked gas and oil as sources of energy for our university, do now hold and occupy Centennial Quad. We shall continue doing so until Gilligan University’s administration halts the threatened despoliation of Blackwood Forest, and commits the university to renewable energy. Blackwood, Blackwood! Sacred Space!” Weston shot the entire ceremony on video. He immediately blasted it to our social media followers.

I saw Em wrapping her arm around Nick. She whispered, “Les jeux sont faits.”

“Oui” he replied. “The die is cast.”

The chants continued as dozens of tents, yurts, canopies, tables and sleeping gear were pitched across the Quad. Lanterns, like constellations of stars, began to light up the historic green. At the main portal, a dozen students unfurled a large banner over the top of the gate. It read: Occupy Centennial Quad.

No police appeared.

Nick located Katherine. “Any luck contacting Redlaw?”

“No, but I’ve left two more messages.”

~

Back at the command center, Helen Flintwinch nodded and spoke into her cell phone. “Uh huh. How many would you say? Holy shit. And they’re what? Oh God! Okay, let me huddle with Annie and get back to you.”

Annie Barnhill, a Gilligan summa cum laude graduate in 1990 and a twenty-year veteran of the Cincinnati Police Department, comprehended the situation before Helen Flintwinch had spoken a word. “So, they’ve taken over Centennial?”

“You’ve got that right,” replied the Provost. “Look at this video.” On the provost’s phone, there was Nick declaring that the Quad was theirs.

“They sure didn’t waste any time going public. Helen, are you inclined to have us nip this thing in the bud?”

“To be honest, Annie, I’m not inclined to do anything until I talk to Mitch, er, President Redlaw. Give me a few minutes.”

The provost retreated to the conference room. She tapped in the president’s mobile number. It went straight to his voice mail. She left a short message then recalled that she had a backup number. “Hello, is this Roger O'Malley?” she asked. “Good. This Dr. Helen Flintwinch in Argolis. I am a colleague of your neighbor Mitch Redlaw. He’s not answering his phone. I need to speak with him urgently … Oh, he is? Great. Thank you.”

Ten seconds later the president answered. The provost got down to business without pleasantries. “Mitch, we’ve got a delicate situation on our hands. Centennial Quad has been occupied by hundreds of Blackwood protestors. Annie and I need to know how you want us to handle this.”

There was a heavy pause. “Let me check my messages first,” the president replied.

“Okay,” she said. “Be quick about it. Annie’s people are keeping an eye on things but we have no idea where this is headed.”

~

Katherine, Nick, Em, and I decided to take a break from the cacophonous quad. We wandered down to The Eclipse Coffee Company. We ordered coffees and settled into a cushioned booth. Apart from two other customers lost in their smart phones, we were alone. Only five blocks from the crowds uptown and only a stone’s throw from Centennial Quad, The Eclipse was eerily still.

Our conversation about the march and the occupation was interrupted by ring tones on Katherine’s phone. “Hello, oh yes President Redlaw, thank you for returning my call,” Katherine said, the only response she could possibly have come up with in this tense moment. She continued, “Yes, what you say is true. I attempted to inform you of our plans several hours ago. Yes. Well, sir, you understand what we are asking, I believe. We intend to occupy Centennial Quad until we have assurances of your administration’s agreement to our demands. Yes, yes, we understand the risks. But let me explain to you that the situation has shifted since our meeting. We have relevant information that could stop Morse Valley Energy in its tracks, save Blackwood, and hopefully coax the university toward renewables much sooner than planned.”

She briefly spelled out the details of Adrienne’s disappearance, of the uncertainty of Morse’s whereabouts, of detective Wesley Rollins, and the likelihood that Dr. Tulkinghorn had blackmailed Morse. When she had finished, there was silence. Looking across at Nick, I could not read his inscrutable expression, partly hidden by his Expos cap, but Em’s eyes were locked onto mine. I smiled back at her and raised my eyebrows expectantly. Em’s reassuring smile was pure and I took heart from it.

After what seemed like hours, the president spoke. “No sir, we won’t,” she replied. “We pledge not to release any of this information for twenty-four hours. This will give you time to verify what we have gathered. However, if we have no response from you in the next twenty-four hours, including an opportunity to meet with you personally, we will have no choice but to call a press conference. Yes, sir, we are very serious.” Another pause. “The Occupation?” she seemed to repeat. “Yes, of course, we will continue it as a non-violent form of protest. We will respect Centennial Quad grounds and plantings, the buildings, the space; there will be no deliberate damage or violence.” In response, the president seemed to be making a request. “Alright,” Katherine said, relenting in tone. “Yes, I think we can stretch that demand. Yes, sir. Before I hang up, I want to stress that we hope you and the police will honor our expressed form of non-violent protest until you meet with us or the situation is resolved to our satisfaction. I must also tell you that we have several thousand people keeping track of Occupy Centennial Quad on social media.” Another long pause followed. Then she said, “Thank you, President Redlaw.” She placed her phone on the table.

“Whew.” She let out a long breath.

“Then we’re set for the next twenty-four hours?” I asked.

“A bit more. He asked us to hold off any press conference until Sunday. He said that as long as the occupation was peaceful, the police would be at the periphery to provide security, especially tomorrow night. He said he would instruct them to open Weary Hall so we can have access to the bathrooms. There will be an officer stationed at one of Weary’s side doors.”

“And he pledged to meet with us?” Nick pressed.

“He did. Sunday morning at nine.”

“Fantastic job, Katherine,” declared Nick.

“Bon, well done!” Em exclaimed, and in solidarity we each stacked our hands one on top of the other. But in the recesses of my heart, I sensed the unraveling of all my presumptions of order, the specter of emergent properties, and the ambiguity of a future I dared not summon.

7

As the chimes in the Stiggins steeple struck 9:00 AM, we — ten rumpled students and one obviously sotted classmate — filed past Lisa Van Sickle, the campus police officer assigned to the front door of Stiggins Hall. As we passed, the officer avoided eye contact with us misguided losers for whom she had little sympathy or patience. Her right hand, the one on her holstered revolver, twitched.

José pulled Katherine aside. “Astrid’s on her way,” he whispered.

We took our places and, except for Zachary, we began boisterously sharing exploits of the weekend. Zachary was in a stupor, the result of over-indulgence that wildly exceeded anything in his brief résumé of imbibing. Jason, the Australian grad student, sitting next to him, said, “Zach. You’re looking a bit green around the gills there mate.”

“I’m not well, man,” Zachary admitted weakly and dropped his head to the table.

~

Excerpt from Dr. Helen Flintwinch’s testimony to the GUO Board of Trustees, January 2014:

~

In President Redlaw’s office, Beth Samuels and Helen Flintwinch were putting on a show, fiercely disagreeing while virtually ignoring the President. He let them roll, listening calmly, his elbows resting on the polished walnut desk, his hands pressed into a tent that touched his chin.

“Beth, we’re damned if we do and damned if we don’t,” the provost argued.

“I don’t see it,” Beth retorted.

“I do. Based on a quick look at education and news sites this morning, we’re already awash in what looks to me like bad publicity. Even the New York Times website had a small piece on the occupation. And, as far as I know, local and national media have yet to send a real person here since the occupation. Their coverage is being generated by student tweets, Instagram and Snapchat pictures and videos, and Facebook posts. The students are controlling the message for God’s sake. I say issue an ultimatum to these protestors. Force them to clear the quad by nightfall. If they don’t disperse, threaten to send them to Student Judiciaries tomorrow, one-by-one.”

“So, Helen,” Beth Samuels cut her off. “You are advocating shutting this occupation down, an occupation that is arguably a form of free speech. I don’t know how to respond except that, as a solution, your reasoning scares me. It sounds like Mubarak in Tahrir Square.”

“Who’s in control here? The students or the University?”

The two, speaking on top of one another, were hardly communicating. It was as if they had recorded their comments in separate rooms.

“Beth, my dear, I’m obviously playing devil’s advocate. Meanwhile, back in the real world, just a couple of hours ago, Governor Winthrop proposed calling up the Ohio National Guard and sending them here. Once he makes the decision to deploy them, we stand back. It’s not on us. Let him take the heat.”

“A brilliant strategy!” Beth countered. “Centennial Quad is cleared by armed soldiers. Hoorah! Imagine: students shot, or bludgeoned, or bayoneted, or gassed, or all of the above; dozens jailed. If that happens, we’re on tap for much nastier publicity than now, not to mention potential casualties and possible deaths on our consciences and a brutal repression of free speech. Gilligan becomes a pariah. Enrollment plummets; we’re forced to fire faculty; our research funds dry up as do alumni donations; maintenance and modernization of our facilities are further deferred, including the move to renewable energy. The place becomes shabbier and shabbier. Enrollment drops further. What a happy downspiral.”

“I don’t appreciate your sarcasm, Dr. Samuels,” the provost sourly replied. “Nor do I grant that bloodshed would happen. The bottom line for me is that we cannot allow anarchy on our campus. We must not let students dictate the way …”

Beth cut in again. “It doesn’t look like anarchy to me, Helen. The occupation so far has been orderly, respectful, and non-violent. The students are being lauded all over the Internet for taking a stand against fracking, for promoting renewable energy, and for speaking knowledgeably and non-confrontationally about climate change. Those could be, probably should be, our messages, but we’ve been out-maneuvered and, to be honest, out-smarted.”

“Oh great goddess of messaging, what would you do?” the provost responded with weary disdain, smirking at her adversary like a person who is fully aware there is no humor in the room.

“I would try to buy time. I would ask the students to hold off reporting their allegations to the press and I would emphasize that, as long as this occupation remains peaceful and does not disrupt our main mission — education — and that we finish the semester as planned, we let them retain their tented village. We would then come across as open-minded and on the side of free speech and non-violent civil disobedience. We would engage them in a game of delays. They are, after all, students who must attend classes and pass their courses. When November arrives, with its cold winds and stormy weather, I predict the quad will empty very quickly.”

“That’s all fine and good but what do we do about Morse?”

“Morse. If we can track him down, I suggest the president and Governor Winthrop force him to meet with them to resolve this standoff. The Northeastern Regional Campus could come back into play.”

Helen Flintwinch was in the sourest of humors. Later she might regret having engaged Beth Samuels in such a rancorous and disrespectful manner, but now she needed coffee. She abruptly turned her back on the debate and marched to the outer office. She called back, “Isn’t there any damned coffee here, Mitch?”

“None freshly brewed. I brought mine from my palatial mansion across the street. Mrs. Wickett is off to Pittsburgh to help with the birth of a grandchild. As you know, I have no wife and today no maidservant. Miraculously, I brewed it myself.” He wondered: How can I manage to find humor in face of a potentially ruinous end to my reign?

The president rose and ambled across the office toward his media relations director. She stood at the window gazing toward Pan’s statue. He stood next to her, silently, a few moments: two ageing hoopsters about to face opponents more implacable and less predictable than any they had faced in their innocent heydays. He spoke conspiratorially, perhaps fearing the provost would return to unleash wanton chaos in his chambers. “There’s no easy way out, Beth. The Ohio National Guard is the worst of all options, as I told Governor Winthrop an hour ago. He needs to read up on the governorship of James A. Rhodes, the one who last called up the Guard for an Ohio campus disturbance. We all know where that led.”

“Sure don’t want that,” Beth agreed.

“As for Blackwood, none of us has been able to either substantiate or invalidate the students’ allegations. Morse has gone to ground. Beyond admitting there is a missing person, the detective in the Virgin Islands refuses to divulge details about his investigation or to speculate on Morse’s whereabouts or his connection to the missing person. Tulkinghorn zealously denies blackmailing Morse. I hate to admit it,” the president said, “but I cannot imagine how these allegations could have been fabricated and I dare not take them lightly.”

“So, what do we do?”

“I believe we must somehow convince the students to postpone going public for a while longer, slow-walk them, as you suggested. With borrowed time, we might just weasel out of this mess. And thus, my good woman, I believe we are drawing from the same play book.”

“Alright, sir, listen up. Here’s how we’ll frame things.” Back on the edge of the paint, in the dying minutes of a championship game, her munificent physique poised and controlling the pace, Beth Samuels knew exactly what she needed to do.

~

Astrid slipped into the briefing room on the heels of President Redlaw and Media Relations Director Samuels. She handed Nick a folded sheet of paper. As Nick read it, his eyes widened. He passed it to Katherine.

I regarded the president’s red-rimmed, basset hound eyes. I could see that events were taking their toll. He seemed to suspend eye contact when meeting my direct gaze, as though he were afraid to admit something shameful.

“Thank you for coming here this morning,” he began. He looked around, noting that the brilliant and tenacious Zachary from Sandusky looked dangerously unwell. Though several students sat between the president and Zachary, the president (and the rest of us) could detect boozy vapors off-gassing from Zachary’s every pore. The stink was eye-watering. Serves him right, I thought.

President Redlaw turned his gaze to the others. “Although we are in the midst of what appears to be a standoff, I believe we are all well served by the openness and civility of our communication. I hope we may continue to work in this forthright way toward a resolution. Director Samuels showed me the video clip of Nick’s declaration at the onset of your occupation. That, together with Katherine’s call Friday and this press release you just handed me, stakes out your position with unusual clarity. Your demands are reasonable responses to what you perceive to be the hazards of hydraulic fracturing and the potential risks to a cherished natural area, which, it is true, we pledged to protect but are now obliged by law to relinquish. That there is a connection between the natural gas under Blackwood Forest and our campus energy plan is undeniable. We view natural gas as a cost-effective and lower carbon bridge to the time, in a decade or so, when we can begin the transition to renewable energy. That argument is also well known to you. So, I think our respective positions are clear enough.”

Beth Samuels tried to make eye contact with everyone, sweeping her shining brown eyes, much more alert than Redlaw’s, in a grand circle. “I’ll say this”, she began, “you and your followers are exceptionally well-organized and media savvy. After this situation has been resolved, some of you might think about documenting it as a case study: how it evolved, the process of decision-making, and what your proposals ended up achieving. It could be the basis of a great article for, say, the Journal of Communication and Environmental Affairs.”

Her remarks felt like pure patronization to me.

Nick, too. He said, blandly, “Thanks for that.”

As scripted, the president took it from there. “As Beth mentioned, we have tried to check the facts regarding what Katherine has described as new developments. Unfortunately, so far we can neither confirm nor refute them.”

“That puts us in some kind of pickle,” Beth added.

The president smiled at her theatrically. He scrunched his forehead and put on a humble expression, as if begging for bread crumbs or pickles. He said, “So, I want to propose that your steering committee refrain from meeting with the press for another five days while we seek further verification. In the meantime, as long as your occupation of Centennial Quad does not interfere with classes and other vital university functions, it may continue unabated on its present terms.”

Katherine gazed at Redlaw and Beth. She subtly winked at Nick. She cleared her throat. “Thank you, President Redlaw. As you surely understand, our group will need time to consider your request. Meanwhile, we have recently uncovered more data that can speed the verification you seek. Astrid Keeley will present this information.”

Astrid sat upright in her chair. The president smiled extending an open hand toward her and asked, “Are you not the woman who argued for renewable energy in a town hall meeting in the basement of … where was it? … Morgan Hall?”

“Yes, I’m the one from Morgan,” replied Astrid. “I was surprised you did not recognize me last week.”

“Me too,” he said. “Your face somehow just popped into place for me.”

I thought: How could he not have remembered her — her dreads? Her swag?

Astrid put on her earnest face and said, “Well, Mr. President, I have some leads for you. I believe they will strengthen the foundation of our allegations of collusion between Dr. Tulkinghorn and Jasper Morse on the Larnaca Chair, and the whereabouts of Mr. Morse, along with his possible involvement in the disappearance of Adrienne Foster.

After Astrid had concisely summarized her new findings, the president responded, “In normal circumstances of university discourse, I would want to know your sources. But in this case, I sense that perhaps it is best that I do not ask.”

“Yes sir, that would be a wise choice. We do, however, encourage you to check out these means of verification.” She handed him a sheet with her contacts. Bemused by Astrid’s confidence and the specificity of her intelligence, the president scanned the document. To Astrid’s surprise he then looked directly at her and chuckled, shaking his head wistfully. “I must say that receiving such obviously clandestine information, derived by an intrepid investigator, who is simultaneously a graduate student, is a stunning indicator of how much of a mossback I’ve become.”

“Undergraduate student, sir.”

“Even more impressive!”

When we reconvened, we reported that we had reached consensus on giving the administration not the five days they had requested but instead four days, as long as the president promised not to interfere with the occupation and disrupt our plans for a teach-in. Regarding the teach-in, Redlaw said, “Now, Beth, you’re too young to remember, but these guys are reviving a protest strategy from the sixties.”

The president then cautioned us not to neglect our homework. “I’ll be calling your moms and dads if I hear that you’ve flunked any quizzes.”

Nobody even broke a smile. Beth put on the slightest eye roll, I noticed. I found it amusing, a gesture of admiration really, a tenderness there.

En route across the quad, I walked with Em and Nick. Em told us, “That man's becoming like my grand-père. I think he is comfortable playing this role.”

“A shifty grand-père.” Nick replied. “I wouldn’t trust him with my grandmother’s sister.”

8

Alongside the small platform I gazed up at Dr. Sophie Knowles speaking to no more than a dozen of us scattered on the grass. It was another sun-washed late October morning on Centennial Quad. Sleepy occupiers crawled out of their tents and yurts and wandered toward the food. Sophie was lecturing about the risks of deep-well injection of wastes from fracking and its connection to a rash of earthquakes that have shaken states like Ohio where faults had long been dormant. Stefan stood nearby. He waved at me just before Dr. Burt Zielinski ambled up alongside him. Per Stefan, here’s what they were whispering about:

“Not much of a turnout at this hour for Sophie,” Burt said. “Are you next?”

“No sir. You are,” Stefan replied. “Looks like they’ve jammed the program this morning with C-Nerds. Maybe we’re the only department foolhardy enough to ally with these renegades.”

“I hope that’s not the case,” Burt said. “But I’m not confident that any of this posturing will deter Morse. Probably he’s already out there firing up his rig. And besides, isn’t this idea of a teach-in rather passé?”

“Yeah, in these days of instant digital gratification and terse communication maybe the teach-in was not such a good idea.”

“Well, if this audience is any indication, I’d say the movement is in trouble.”

“It’s early in the day and they reportedly have thousands who follow them on Facebook and other social media. See that guy over there in the blue blazer?” Stefan pointed at Weston. “He’s shooting video of each talk. A video collage will be sent out to all those followers.”

“Still not impressed,” Burt crinkled his eyebrows and shook his head in doubt. He told Stefan he could not understand what social media could possibly have to do with forcing the shutdown of drilling at Blackwood Forest and demanding the university to go green. What he knew of Facebook consisted of pictures of his grandchildren and incessant drivel from his sister in Florida.

Classes were changing as Burt’s talk on climate change concluded:

“Our climate, which has served humanity’s evolution so comfortably, is about to get ugly. But far worse than that, climate change will present your generation with widespread famine, unprecedented heat, catastrophic human pandemics, swamped coastal cities, colossal storms like Katrina and Sandy, and massive streams of refugees. If we don’t greatly reduce the emissions from dirty fossil fuels, if we don’t reverse our spewing of greenhouse gases, we are headed for disaster. Since I myself will not likely have to suffer through any of this, I wish you and your generation the best of luck. And I pray that my grandchildren will live on high ground and will have learned how to feed themselves.”

The crowd of some three-dozen clapped, at first an underwhelming response, then at Zachary’s hooping insistence, we all rose for a prolonged standing ovation. Hundreds of students meanwhile scurried across Centennial Quad as classes changed. Some stopped to converse with occupiers who handed out programs and copies of our press release. By the time Stefan spoke, the audience had increased to about fifty. When he stepped down, the Stefan-heads, including me, flocked to him. “Awesome talk,” Nick complimented him. Em gushed, “Prof Stefan, I liked it when you compared today’s times to the Roman Empire when it was being stretched toward its own disparition. Oui, collapse!”

Katherine cast a sidelong glance toward Stefan. “Hit it out of the park”, she said, winking. He returned a giddy smile. How shall I name that scene? Delirium?

“Thanks guys. Nothing new for you but I hope it fires up your troops.” Our group was joined by still more groupies. Greg asked, “Hey Stefan, do you think this protest has any chance of shutting down the drilling at Blackwood?”

“It’s too early to say. Its success will depend on engaging a larger portion of the Gilligan student body than these few here.”

“The crowd here’s not the point, Stefan,” José insisted. “Our video blasts on YouTube and Instagram and to our Facebook and Twitter followers will inspire everybody for the next round.”

“And what would that be?” Stefan asked

“Well, it all depends on what Morse and President Redlaw and company do next. We’re nimble. We’re reflexive, you know. We’re ready to respond to the emergent properties of this complex system. Yo' hear what I’m sayin'?”

“I certainly do,” Stefan replied grinning.

By mid-afternoon the teach-in was winding down. The sixty or so hangers-on who sprawled across the grass in various languid and occasionally libidinous poses were either half asleep or in various states of hormonal distraction. We gradually came to life with music that echoed across the quad — a beguiling set of seventies folk-rock tunes delivered by Jude Hawkins, a long-ago Gilligan student who never graduated because he had abandoned Argolis for Nashville during a few brief months of fame. Now on stage with his little band — a base guitar, drums, and a keyboard — the gravelly-voiced Hawkins sang and strummed and played his harmonica through a dozen tunes from those good old days. Between tunes, he entertained us with banter about what it was like to be protesting the American war in Vietnam and the plight of the Earth “right here, my friends, right on this same shady lawn, right here in this bubble called Argolis.”

I gazed up at Jude Hawkins. He seemed a fugitive from another planet: this rail-thin man the age of my late grandfather with his Willy Nelson ponytail and scraggly facial hair, wrinkled brow and crow’s feet looking more like ostrich feet, his flushed complexion that of a man, like my dad, who loves his bourbon. Yet, while typically dismissing our parents’ generation of music, I and my fellow students had the opposite response to Jude Hawkins performing our grandparents’ kind of music. We grooved on his Bob Dylanesque rasp, his harmonica and guitar riffs, his political lyrics. We began to gather closer to the stage and clap and swing to his music. When it concluded, we hooted and cheered for more. That’s when Jude Hawkins sang about a protest in Argolis, a song that put him on the cover of Billboard and sent his single into the top twenty on the pop charts for those few magical weeks of 1971. And after three verses, we millennials joined him on the chorus:

There’s blood on the bricks in Argolis Town.

There’s blood on the bricks where people stood fast,

An' their blood sears our memory of those so beat down,

Those heroes begging for peace at long last.

There’s blood on the bricks in Argolis Town.

Stefan arrived just in time to witness this unlikely scene. He squatted next to me. “Isn’t this amazing how the scene bridges four decades of Gilligan dissent? But I don’t know whether I should I feel possibility or futility here.” I had no time to fashion a response beyond a lame, “Yeah,” because we both were immediately drawn to the last speaker of the afternoon.

Melissa Caldwell, the self-proclaimed battle-axe single mom in our class, had the honor of introducing Rutherford Bosworth Hays. She began by reciting Boss’ history as a Vietnam-era Army veteran and peace activist. She said that for decades he had been a Grieg County farmer and environmentalist. “Like me, this man is native to this land. And like this land, he has been battered by life’s struggles and the suffering brought on him and this planet by evil-hearted people. He has chosen to put aside that baggage to dedicate his life to making this green Earth — this place that he and I love beyond loving — to making our home a haven of peace and of ecological wholeness. With me, please welcome Rutherford Bosworth Hays.”

Led by students in our class, people stood and applauded, long and loud.

Boss hobbled up the steps of the platform, hugged Melissa, and shouted out “Now you all cease that noise. Settle down.” After he had thanked Melissa for “that overly kind description of me”, looking down at his boots, and shaking his head, he confided, “There are many more people 'round here who would sooner label me an ornery varmint and, to tell you the truth, they wouldn’t be far off. Hell, I ain’t no rock star or even a folk singer like my friend Jude over there.”

Jude Hawkins, lounging on the grass to the left of the stage, called back, “That ain’t what I heard.”

Boss began his talk by saying, “My friends, you know, I could talk a long time about the evils of fracking and what havoc it’s gonna bring to these hills. But I suspect you’ve had more than enough of that today. Instead I want to tell you about the native beauty of my farm. Well, as some of you know, I got one hun'red acres of some of the richest biodiversity on this planet — these Appalachian Ohio forests — these sacred forests blessed with ample moisture and good soil and a legacy that goes way back before the glaciers. The plants and animals and trees simply astonish me in their variety, beauty, and healing power, every day. Now, I never got me a college degree, but I want to tell you that, after more'n thirty years down here, my farm has conferred on me a degree better'n any I might've earned in a classroom. Yep, my degree is in lovin' nature with a minor in Earth mystery, which is to say I am lucky to have gained awareness of how all beings are linked together in whirling circles of life and death and rebirth. Life, 'n death, 'n rebirth. Keep in mind that last part: rebirth: that’s the hopeful part. Well, them're my credentials, folks.” He paused to wipe his brow with a bandana.

We applauded. Boss hushed us again and went on to explain the rhythms of his life: daily, seasonally, and through the years. He said, the rhythms are simply circles, “just like one o' them carousels.” Then, to everybody’s surprise, from his shirt pocket, he drew out a harmonica and unleashed a solo that soared across the quad, reaching perhaps to the second-floor office of Provost Helen Flintwinch. Drawing more and more students toward the stage as he, with knees flexed, his head bobbing, his foot stomping to the beat, Rutherford Bosworth Hays wailed and wailed. Several of us, including Stefan who I boldly tugged into the line, locked arms in a swinging tribute that linked our generations. Then Boss ceased in mid-bar. In the unforeseen stillness, with a subtle twitch of his beard, he gestured toward Jude Hawkins.