“There are no records. So you can claim whatever you want.”

—YUSUF NUR

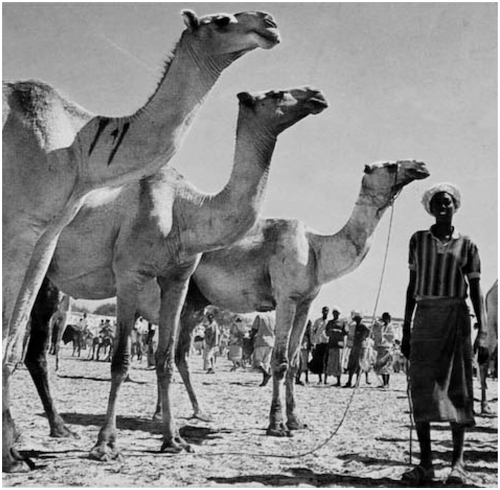

Camel market, Mogadishu, 1960s. OFFICIAL MOGADISHU GUIDEBOOK, 1971

IT ALL STARTS, I SUPPOSE, with a lie. Or perhaps it would be fairer to call it an invention.

“I was born here in Mogadishu. My mother came here when she was about nine months. Then she had baby. This baby was me,” says Tarzan.

He has an abrupt, intense way of speaking. His brown eyes dart, as if I’m not enough of an audience and he’s sweeping the room for other reactions.

It’s just gone dark, and we’re sitting on the covered terrace outside his house, just below Villa Somalia, the mosquitoes whining lazily at our ankles. It’s the last week of Ramadan—a hot, sluggish time in the city—and Tarzan is breaking his daily fast with some dates and a sip of tea, and waiting for Shamis to come outside with a tray of hot food.

The narrow terrace runs along two whole sides of their house. The walls are a pale yellow, the floors covered in white tiles, and the outside arches and corners are crowded with dozens of plants in white pots. That’s Shamis’s touch. She’s worked hard—in part to kill the boredom of what sometimes feels like a prison—to create a homely atmosphere. The terrace could almost be a little café, with its plastic chairs and round tables, each with a plastic tablecloth.

Shamis brings out a thick, porridge-like soup called marak, which Tarzan loves, a plate of fried liver, some pasta—a nod toward Italy’s role in Somalia’s colonial past—and then Turkish baklava to finish.

She’s wearing a long yellow dress, and she drapes an arm on his shoulder. It’s a casual gesture, but here in Mogadishu, where women now feel the need to wear a veil in public, it seems boldly intimate. It’s not the first time I’ve been aware of the electric jolt of affection that seems to flicker between Tarzan and Shamis, even after all these years together. I know their children are quietly proud of it—other Somali parents seem so much more restrained.

Tarzan speaks English quickly and confidently, in a guttural accent—part London, part Somali—pronouncing “months” as “month-es,” with an emphasis on the last syllable. Most plurals get the same treatment, and it’s only some time later, when I’m talking to an Italian who grew up in Somalia, that I realize where that extra syllable might have come from.

“I was born in the Martino hospital. Room 18,” he continues, wafting his hand in the general direction of the sea, then waving at two men who have just walked onto the terrace and quietly taken seats in the corner, as if waiting for a doctor’s appointment. Tarzan is in his casual clothes—bare legs and feet, a long sarong-like macawis, and a black short-sleeved shirt.

“National health! Free. The Italians controlled the hospital. Nuns. Nuns! They were my midwives. It was 1954.” Tarzan is enjoying himself.

The San Martino Hospital—a ruin these days—was once a landmark in the city, right on the seafront, about a mile away from here. Tarzan looks nostalgic as he describes the circumstances of his birth, how his mother dutifully made the long trek from the wilderness of the Ogaden, where the family lived as nomads; and then how she returned with her newborn son, to her husband and firstborn, immediately after Tarzan’s birth.

Except that it’s not true … none of his birth story is. But it will take me a while to discover that, and much longer to work out why he feels the need to reinvent himself.

Shamis has brought more tea to the table now, and some honey to stir into it. I’ve got my notebook out and I’ve written “Room 18” and underlined it. It’s a resonant detail, I’m thinking. Not something I’d have remembered about my own birth.

At this point, I’ve been visiting Somalia, on and off, for twelve years, as a journalist for BBC News. I can feel the place burrowing into my skull. There is something uncomfortably bewitching about some conflict zones. I’ve felt it in Chechnya, Iraq, Afghanistan, Liberia, and in plenty of other countries. But there is a particular intensity to the experience of visiting Somalia, and it’s hard to pin down why. The sunbaked ruins are spectacular, and the people are impossibly, jaw-droppingly resilient, but it’s more than that. It feels like a place untethered from the outside world. A city that has suffered for so long that war has become the status quo.

It’s August 2012—two years before the attack on Villa Somalia’s mosque—and two years since I first met Tarzan.

Visiting Mogadishu, particularly as a foreigner, is a risky, expensive, and, above all, logistically complicated process. Who guards you—a particular clan, foreign peacekeepers, the UN, private security contractors? Do you stay with the military, or in a hotel, or with the government? Which rumors to believe? What security advice to trust? Should you avoid all convoys? Is it safer to keep a low profile in a small car, or to hire a dozen guards? Will the budget stretch to bulletproof windows? What does bulletproof even mean, in practice?

The result is usually a string of short, slightly frantic trips.

Tarzan caught my attention from the start. It is, you might say, in his nature to do so. He’s impatient, outspoken, and refreshingly different from almost every other politician I’ve met here. Most are cautious to a fault. And who can blame them? Perhaps Tarzan is a little too media savvy. I always feel slightly suspicious of anyone who actively wants to talk to a journalist. But still, I’m intrigued.

Boom … There’s a hollow-sounding explosion, a small one, a few blocks away. Shamis has joined us at the table and looks around sharply, as do I. Tarzan continues to sip his tea and quietly announces, “Grenade.” Sure enough, tomorrow’s Somali news websites will confirm that a grenade was thrown in the market, just a few hundred meters away, in an area known as Shangani.

This is the third evening in a row that I’ve spent breaking the Ramadan fast with Tarzan and Shamis at their small home, and I’m slowly getting used to the unusual feeling of being outside the regular security bubble that has, in varying forms, dominated every other trip I’ve made to Mogadishu.

I was dropped off at around 6:00 p.m. Eight local armed guards, from the foreign-run guesthouse I’m staying at near the airport, drove behind our car and waited at the security barrier at the end of Tarzan’s rubbish-strewn cul-de-sac, as we went on through. A tall, cheerful, eastern European security advisor—who rather spoiled the mood on the journey by reminding me that the bounty on a foreigner’s head is between US$1 million and $1.5 million—then got out of the front passenger seat of our car, briefly assessed the situation, came to open my door, and escorted me into Tarzan’s house, past an elderly man sitting beside the bright green gate with a Kalashnikov on his knee.

And now I’ve been transferred—and it’s hard not to feel just a tiny bit like a hostage—into the hands of Tarzan’s own security team. On previous nights, his eldest son Ahmed drove me back, on his own, to my fortress-like guesthouse, picking his way through the dark back streets, past several sleepy crowds of goats, and through a handful of army checkpoints.

It’s a year now since the militants of Al Shabab abruptly withdrew from Mogadishu, in the middle of a famine, and the city is currently enjoying a period of relative calm.

On the terrace, Tarzan turns in his seat to beckon the two men who’ve been waiting for a chance to talk. It’s been like this every night—a steady stream of uninvited visitors hoping to bend the ear of the mayor of Mogadishu. The men are from his clan. One wants to become an MP, the other is his lobbyist. They’ve traveled 400 kilometers from the town of Beledweyne, in the hope of securing Tarzan’s endorsement.

“I don’t know,” says Tarzan, when the men finally leave. He thinks the would-be MP “talks too much.” He scratches at his elbow and then lashes out at the mosquitoes around his ankles.

Shamis, meanwhile, has had enough of playing the politician’s wife for one day.

“When Ramadan is finished I’m not allowing it anymore. I tell the guards, ‘Don’t let anyone to come here after five o’clock! No more.’ Cos I want to be alone with my husband. When you are at work people should go to your office, but this is my place and I want to be alone with you.” Her English is less polished than her husband’s, but she speaks with warm, almost theatrical intimacy.

Tarzan chuckles. It’s evidently not the first time they’ve had this discussion.

“You’ve become English woman! You are not Somali anymore,” he teases.

More visitors come and go. Fresh tea is poured. Late in the evening, the business calls thin out, and an old school friend drops in, then the lady who lives across the street. And finally I’m back in Ahmed’s car, and he’s driving too fast as we go down the hill, through another, bigger security barrier beside the old national theater, then right and along the main road toward the airport.

Ahmed repeats his mantra, “Mogadishu is quite safe,” in a distinctively London accent. But he’s clearly still edgy about the militants of Al Shabab. “You can’t trust anyone here. At least with your own clan you can vet people, and trace stuff back if things go wrong.”

Ahmed—his father later admits to me—has been brought back to Mogadishu in order to be “straightened out.”

“I’m just trying to find my niche here, cos it’s—like—a blank canvas, a lot of things missing. So I’m importing security equipment for now … from Dubai.” Tarzan’s critics claim Ahmed has been winning contracts improperly, because of his father’s influence.

Ten minutes and a maze of side streets later, I’m knocking on the giant metal gates of my guesthouse, watched by the displaced families still camped out in their ragged tent across the street, and by the armed guards manning the guesthouse’s turrets, who peer down and then give a shout to let me in.

* * *

FOUR MONTHS PASS, AND finally, I manage to get hold of Tarzan’s younger brother, Yusuf, on the phone. It’s not been easy to track down his number. Tarzan will talk all night, face-to-face, but he’s notoriously sluggish when it comes to answering phones, emails, and texts.

“He’s not a good communicator,” Yusuf concedes. It’s a bit of a family joke. “We Somalis prefer talking to writing anytime.”

Yusuf is at home in the United States, with two teenaged daughters and a crumbling marriage. He’s a professor, driving every week into Kokomo, near Indianapolis, where he teaches business studies at the university. In his spare time, he’s become a fanatical mountain biker.

“It’s a two-hour drive. Let’s chat.”

We fall into a pattern of arranging phone calls while he’s doing the commute and, later, on his travels—to northern Somalia, Dubai, and even Taiwan, where his two daughters end up spending a summer teaching English before taking their father on a cycling holiday.

“Hands free, I assure you,” he says on the first call. “I’m heading north on Highway 37. It connects my little town to Indianapolis. Sometimes I spend the night at the university. Like tonight—I have a late class. I wish I lived in the countryside, but the children would not let me do that. I’m the only Somali in Bloomington, believe it or not! Well, I wouldn’t know for sure, but there’s no community, so the only way I’d know if a Somali was in town is if they come to the mosque. There are no Somalis at my campus, either. Indianapolis started bringing refugees in the late nineties and I went to their section of town. They have a restaurant—no food, but a hubbly-bubbly, a water pipe [hookah]. And people chewed khat [a mildly narcotic leaf chewed with vigorous enthusiasm across Somalia]—illegally I guess. I can’t stand smoke, so that was first and last time I went there.”

As you may have gleaned, Yusuf is a details man, a natural teacher. He’s garrulous and charming, too, with a light American accent and an unquenchable enthusiasm for explaining Somali words and customs.

“He told you that?” Yusuf laughs when I ask him about Tarzan’s birth, in room 18 at the San Martino Hospital.

But then he quickly changes tone. His brother is a public figure, and he doesn’t want to be disloyal. Eventually he settles on a diplomatic but still revealing truth.

“There are no records. So you can claim whatever you want.”

“I was born under a tree. It was the most natural birth imaginable,” says Yusuf, and as his neat, precise tones zip down the phone line from Indiana, I start picturing the dry wilderness he’s talking about.

* * *

“IF YOU DRIVE NORTH out of Mogadishu…” As I write that sentence, I realize it should probably finish with “then you would be a fool.” It’s not a journey to be attempted these days, with roadside bombs, kidnappings, and unexpected roadblocks targeting civilian buses, trucks, and armored African Union military convoys alike. But let’s put those risks to one side for now, and imagine coming out of Tarzan’s house, and turning left onto Corso Somalia, the main road that snakes through the city and out, past the old pasta factory, into the sand-blown, low-rise outskirts. You’ll quickly find yourself crossing a dusty plain on a straight but almost comically potholed road. Perhaps an hour out of town, the dry countryside suddenly turns green as the road enters a region irrigated by the Shabelle River, where most of Mogadishu’s food is grown. The road follows the river’s path upstream.

The Shabelle, meaning a place of leopards, is a meandering river prone to flash floods. It wouldn’t get much notice in most countries. But Somalia has only two rivers of any size or significance. The Shabelle begins in the green Ethiopian highlands on the eastern edge of the Rift Valley, then crosses a high plateau into Somalia, heading straight for the coast before losing its nerve outside Mogadishu, swinging south, and dwindling into a few brackish puddles somewhere in the sand dunes outside the port of Kismayo.

After about 450 lonely kilometers, the long road north eventually forks at the tiny town of Jawiil, otherwise known as Kala Bayr, which simply means “fork in the road.” It’s home to some of Tarzan’s extended family, and “the only one town we claim as our own,” says Yusuf.

It’s rough country—the ragged fringes of the geological bruising caused by the giant Rift Valley. It’s not quite a desert, but rain is often rare and always precious.

I’ve not managed to visit Jawiil. But I once flew to Dusamareb, a much larger Somali town about 200 kilometers to the northeast.

I have two particular memories of the trip. The first is of sitting in the negligible shade of a thornbush just outside town, beneath a blazing afternoon sun, talking to an understandably gloomy man who was scraping a living by gathering scarce firewood from the surrounding plains to sell by the roadside. “I’m waiting for change. But things are just getting worse,” he said, as his wife remained hidden behind him inside a tiny tent, constructed from thorn branches and a blue plastic sheet provided by the UN. He’d once had a home and a job in Mogadishu, but the family had been compelled to flee fighting there, then to flee more fighting in Dusamareb, and was now stranded in no-man’s-land. I looked around me at the flat, hot earth and the scorched sky, wondered how it was possible to survive here, and thought of the well-thumbed book tucked in my rucksack.

Warriors is one of the few foreign accounts of rural life in Somalia. It was written by a British army officer charged with policing the region during the Second World War, and composed in tones as dry as the place. Somalia was “a desiccated, bitter, cruel, sun-beaten” wilderness, marked by its “mad stubborn camels, rocks too hot to touch, and blood feuds whose origins cannot be remembered, only honored in the stabbing,” Gerald Hanley declared.

“But of all the races of Africa there cannot be one better to live among than the most difficult, the proudest, the bravest, the vainest, the most merciless, the friendliest; the Somalis.”

My second memory from Dusamareb is from later the same afternoon in 2009. It was, we discovered, Somali Independence Day. A moderate Sunni group was in control of the town and had just fought off a ferocious assault by the militants of Al Shabab. Outside the bullet-riddled government headquarters in the town center, a group of children, women, and heavily armed fighters had gathered together in a touchingly neat line to sing the national anthem of the period. A local student generously attempted a translation for me and said it was about “waking up and leaning together.” The chorus is, indeed, an unusually and pleasingly bossy list of instructions—a distinct change from the wordless old Italian anthem and the more recent, flowery, and forgettable version. Here’s a more formal translation of the chorus we heard:

Somalis wake up!

Wake up and support each other.

Support your country.

Support it forever.

Stop fighting each other.

Come back with strength and joy and be friends again.

It’s time to look forward and take command,

Defeat your enemies and unite once again.

Become strong, again and again.

Back on the main road north from Mogadishu, a few miles past Fork in the Road, is the long, impossibly straight, contentious border with Ethiopia; the very definition of one of those careless, arbitrary lines drawn on a map decades ago by colonial officials in distant boardrooms. In this case, Britain, Ethiopia, Italy, and France were the main players in a scramble for territory and influence that stretched back at least as far as the sixteenth century, and was only settled in the aftermath of the Second World War. Or half settled.

If you look on any map, you’ll see Somalia hugging the shoreline of the Horn of Africa, along the top edge and down the Indian Ocean, in a fairly clear approximation of the number 7. To the west, Ethiopia appears to jab into Somalia, like a rhinoceros trying to push it, rather aggressively, into the sea. And that’s how many Somalis still view it—that Ethiopia’s border “bulge” is stolen Somali territory, a high plateau still populated by people with far closer ethnic and historic ties to Somalia than to Ethiopia.

“Any child my age grew up knowing of Ethiopia’s enmity to Somalia. Ethiopia is our main enemy. It’s a hyena. It doesn’t want us to stand on our own two feet,” Tarzan says.

On Google Maps today the border is marked by a dotted rather than a solid line “to reflect the ground-based reality that the two countries maintain an ongoing dispute in the region,” as Google puts it.

It is on the far side of this dotted border, inside Ethiopia, that Yusuf was born. And Tarzan, too.

“Our grazing land was almost exclusively on the east side of the river Shabelle, north of the border,” says Yusuf, sketching out a vast chunk of territory inside Ethiopia, widely known as the Ogaden.

“The furthest we go west is the river town of Mustahil. That means ‘Prohibition’ in Arabic. I don’t know why they called it that.”

I’ve not been to Prohibition, but I have visited a town called Gode, a little further upstream inside Ethiopia, and a nearby settlement called Danan. It was one of the first trips I made after moving to Africa in 2000, and I was unprepared for the experience. The region was in the grip of yet another drought, and on a wind-lashed plain outside Danan, I walked toward a cluster of flimsy shelters made of twigs and rags. “Huts like molehills. Dust swirling,” is what I wrote in my notebook at the time. I’d never seen such poverty before. The families inside the molehills were starving, skeletal. They told me they’d traveled 150 kilometers—five days’ walk—to get help.

So that is the picture I’m holding in my head, as Yusuf begins describing his own early childhood.

* * *

“WE WERE DIRT-POOR,” Yusuf says, of the Nur family.

But he’s not looking for pity. Quite the opposite. There is a quiet pride in his voice.

“I was born at a place called Mayr-Qurac,” he says. “Mayr is a special kind of reed, used to make thick mats to cover nomadic huts and camels’ backs. Qurac is the most common tree in Somalia. In Kenya the bark is light, yellowish green, but in Somalia they’re darker brown and shorter. It’s an acacia tree, but a special type. The hardiest tree. That would be our national tree.”

And so I begin to piece together the family’s humble, but for Somalis very typical, nomadic origins. Tarzan’s grandfather had been nicknamed Nur-Baadi.

“Baadi means a lost flock of goats or camels.” Yusuf is driving through a snowstorm in Indiana as he explains this.

“My grandfather’s mother was looking for lost goats and when she found them she went into labor. So she named him after that. All Somali names have meaning. We cling to those meanings—like a Toni Morrison novel.”

Nur-Baadi’s son was called Ahmed, and he inherited his father’s nickname along with a prominent gap between his front teeth and a share of the family’s camels, goats, and cattle. Yusuf would inherit the teeth, too, and he now signs his name “Yusuf Ahmed Nur ‘Baadi,’ PhD.”

And so they moved, as nomads do, around their grazing lands, following the rains and the fresh grass, keeping their wells clean and clear, sometimes staying in one place for a few months, sometimes moving every night to keep up with the livestock, always on the lookout for lions and for strangers.

It must have been a grueling life. And it continues to this day. Indeed many Somali families, wherever they are, still own camels and still have relatives looking after them in the wilderness.

In many ways that nomadic spirit—something both entirely literal and wildly romantic—holds a key to understanding Somalia. It is a country of proudly independent families, deeply suspicious of outside authority, linked together horizontally by paternal bloodlines, clan allegiances, and carefully arranged marriages.

“So and so begets, who begat, etcetera,” says Yusuf crisply.

On a continent so often shaped by chiefs, and by top-down authority, Somalia presents itself as a radical exception, as a constellation of equals. In some ways, it’s a source of great strength and stability. But in the wrong circumstances, it can be quite the opposite. As the old Somali proverb goes:

Me and my clan against the world;

Me and my family against my clan;

Me and my brother against my family;

Me against my brother.

It must have been in about 1950, or shortly after, that Ahmed Nur decided to remarry. His first wife had just died, leaving him with four young children—two sons and two daughters.

Ahmed’s second wife was young and unenthusiastic. Her name was Habeba, and she was about twenty-two years old, an orphan whose parents had died during a drought. Her full name, or at least a good chunk of it, was Habeba Abdi Abdille Omar, and then her nickname, “Libaax.”

Somalis carry their family trees with them in this fashion—a rattling sack of male ancestors stretching back as far as an individual can be bothered, or made, to recall. Some can count back ten or twenty generations. For nomads, it’s a way of defining and shoring up their identity in a world without passports or bureaucracy.

Libaax means “lion” and was a reference to a moderately famous relative, a poet who had fought under the command of a considerably more famous poet in the anti-imperial wars against Britain and Italy in the early 1900s.

Yusuf still remembers a handful of Libaax’s verses.

A married man without a herd of goats

Is like an empty vessel.

His wife will always be destitute and thirsty.

His daughter will go unnoticed,

Looked down on.

Oh Lord, multiply my goats for me,

I will be ever so tenacious in safeguarding them.

Every Somali who has been to school knows the works of Libaax’s commander, the charismatic, divisive resistance leader Muhammad Abdullah Hassan. The British sought to mock and marginalize him as the “Mad Mullah,” but his searing, bloodthirsty poems have endured alongside his legend. Indeed, listening to “The Death of Richard Corfield,” where he celebrates the death, in battle, of an impetuous British colonial officer, you can almost trace a link to the swagger of modern-day rappers, dissing each other, head-to-head:

Say: Beasts of prey have eaten my flesh and torn it apart for meat.

Say: The sound of swallowing the flesh and the fat comes from the hyena.

Say: Crows plucked out my veins and tendons.

(TRANSLATED BY ANDREZEJEWSKI AND LEWIS.)

But none of this meant much for Habeba. Her rich lineage counted for little in a society that, at least in crude terms of reparation and value, seemed to rank camels above women.

“She was forced to marry,” says Yusuf. “There were a lot of orphans in those days. People died young—still die young. So she was brought up by an uncle who just said, ‘Look, you have to marry the old man or I’ll curse you.’ In Somalia that’s like invoking God’s wrath. Somalis believe their parents have that kind of power. She thought she’d avoid the curse by marrying Father—but just for one night, and then escape to town. But she said Father then put a spell on her, and she no longer wanted to leave.”

Ahmed was a tall man, even by local standards. Perhaps six foot four inches. It was said he could load a hand-woven, fifteen-gallon water container onto a camel’s back without needing to force the animal to the ground first. Habeba, by contrast, was unusually short. “Much shorter than average. Barely five feet,” says Yusuf. They made an odd couple. But Habeba soon proved her worth by giving birth to five boys in quick succession.

First came Mohamed, then Mohamud (who would later become known as Tarzan), then Yusuf, Muse, and last, Abdullahi.

Birthdays are not much marked or celebrated in Somalia, but Yusuf, true to form, has since tried to work his out. “My mother told me I was born in Ramadan month. Early on the ninth morning. I used a calculator to convert Islamic calendar to Gregorian calendar. So I was born around May 3, 1955 or ’56.”

I’m keen to understand what it must have been like to grow up as a nomad, to live in a way that can barely have changed in centuries. Tarzan and Yusuf both steer me toward their younger brother, Muse. “It’s the same word as Moses,” says Yusuf. Unlike all his surviving brothers, Muse stayed with the family until he was a teenager, and so it is to him the others defer for the detail, the family history.

But Muse is a hard man to reach. It’s just as Tarzan suspected. “Most likely he will want nothing to do with a book.” He works in Mogadishu these days, for the country’s biggest mobile phone company—an industry that has thrived here with staggering resilience and inventiveness. “He’s the tower guy,” Yusuf says. It’s a job that requires Muse to be able to travel freely around the country, navigating his way through potentially hostile areas to access phone masts and so on.

Muse, displaying the caution only Tarzan seems to lack, makes it clear that he’s worried that any publicity could jeopardize his security and his ability to travel. At one point I hire a local Somali journalist to see if he can track him down in Mogadishu and convince him, but I’m soon told, by email, that “he refuses to be part of the book, saying ‘I am not ready by any means good or bad.’”

So I make other plans.

* * *

MY HOME, FOR NOW, is in South Africa, a country with a big Somali community. In a way the Somalis are like any other group of expats. Over the years I’ve had plenty of opportunity to tap into, say, the Ghanaian community in Johannesburg during their country’s giddy journey through the 2010 World Cup. Or to look for advice from Ivoirians and Malians when their countries were collapsing into civil war.

But the Somalis are different. I’ve never encountered a more closely connected, efficient network. It’s like jumping from dial-up to broadband. Perhaps I’m getting carried away, but I start thinking of all those constellations of nomads, linked across the wilderness by tendrils of blood and marriage, and now extending across almost the entire world, as an alternative manifestation of the internet.

Not for the first time, the Somali novelist Nuruddin Farah kindly offers to help me out. I’ve come to know him first through his books, later at lectures he’s given, and finally through a mutual friend—a Kenyan Somali who used to work for the BBC and is now a member of parliament in Nairobi. He was injured in a grenade attack—probably the work of Islamist militants—and Nuruddin and I met up when we were both visiting him in a hospital in Johannesburg.

So I email Nuruddin, who lives in a book-cluttered apartment just below Table Mountain in Cape Town, with what strikes me as an unreasonably tall order. Can he put me in touch with a young Somali who lives in Johannesburg, speaks strong English, and who was, until recently, a nomad, living, ideally, in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia, where Nuruddin’s clan is also from, and not too far from the Nur family’s pastureland.

“I’ve asked around,” comes the near-instantaneous reply, “and been given the name of a young man. Bashir.”

Sure enough, a day or two later, I’m sitting in the sunshine outside a cafeteria at Wits University in Johannesburg, watching Bashir’s long, strong fingers mimic the steady actions of milking a camel.

Wits is one of South Africa’s top universities and occupies a hilltop and steep, well-manicured hillside just north of the city center. It’s lunchtime and tables around us are filling up.

At first Bashir doesn’t notice he’s even moving his hands, as his thumbs work their way instinctively across the other fingers, in a gesture that seems both rough and oddly tender.

“Psheee, psheee, psheee,” he says, imitating the sound of the milk jetting out and hitting a container. “Even now I can remember exactly how to make milking. This is for the camel. You put like this the breast of the camel. She has four.” Teats? “Yes. Pshee, pshee! But the goats it is like that. Sheee. Sheee,” and his fingers move more gently across each other—more of a stroke than a rub.

Bashir was born in 1985, outside a town called Degehabur, which means “boulder.” It’s just north of Tarzan’s family grazing land in Ethiopia. Their clans were neighbors and would often intermarry.

Bashir Omar “Qaman” in Johannesburg, 2016. COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

“You see, I found it here,” says Bashir, peering at the map on my mobile phone. He is a tall, gregarious man, with a high forehead, an angular face, and eye-catchingly hollow cheeks that he keeps turning, like a sunflower, toward the winter sun. His upper teeth jut forward as he grins, and his long arms move extravagantly as he acts out scenes.

“I was born outside the town, in a small area with wells for cattle. Bulalle—a very famous place.” So an oasis? I ask. “Yeah. I can’t tell exactly which night I was born, but I estimate it was the first of January. Somalis don’t give the day much attention. That’s not the tradition. I like to but…” His voice trails off.

“My mother and father have both passed away now. We were a big family with about five hundred sheep and a hundred goats, and seven children. My nickname is Qaman—it means ‘hero.’ I inherited it from my grandfather.”

A few days later Bashir emails me to explain that his nickname is a bit more complicated than that. Literally it means “the one who does not wait,” indicating a child that gulps at his camel milk and implying a greedy, and perhaps brave, temperament.

The day Bashir was born, his father chose a newborn camel for his son, and to mark their bond, Bashir’s umbilical cord was tied around the camel’s neck. Her name was Duwan.

At the age of seven, Bashir became a dabadhon, or camel herder. “There is one or two of you, depending on the number of camels. My father, most of time, he has between seventy and a hundred cattle. The old ones died because of the famine. So I was a dabadhon, and there is an older man who you go with to find fresh grass for the camels.”

I imagine the two herders trekking into the bush for a few days but Bashir puts me straight.

“Sometimes several months. Then back to where our father is.”

So much for childhood.

Bashir describes one particularly long, grueling trip he says he made as an eight-year-old—just him, a man his father had hired named Shafih, and about 160 camels, the herd swelled by others belonging to an aunt and uncle. Shafih was not good company.

“There is such unkindness toward the young, the dabadhon. They always beat you. He will beat you. He must beat you. If you do a big mistake he’ll say ‘come’ and then he takes a stick from the tree. Not the fist. It is tchee, tchee, tchee.” And Bashir mimes a beating, his arm swinging from high behind his head.

For more than a month the group traveled southwest, heading to fresh pastureland. Finally they turned toward home. At this point Bashir stands up in the cafeteria, to imitate the plodding gait of both man and camel.

“You just walk after, like that. So at about eight at night you need to rest. The older man tells me, ‘You stay with the camel, I need to go ahead. I leave you and camel. You will see the fire at midnight.’” And Shafih disappeared into the scrubland ahead with his small machete, in order to cut thorn branches.

“He’s making a place, a house of the night … What is the word in English?” A cattle pen? “Exactly. Because maybe there is hyena. Sometimes lion.” And he draws me three circles in my notebook, like a Venn diagram, with a big one for the camels, a smaller one inside for the young camels, and another, linking both, for man and boy.

The sun set, and in the dark, Bashir noticed a few drops of rain. He began talking to the camels stomping around him in the dark.

It started with a few instructions. “Whoo,” he half-whistled in a strange, haunting style. It’s a warning note, designed to keep the camels together, “to protect them from being eaten.” Except tonight it didn’t seem to be working. “Hai, hai, hai,” said Bashir, ordering one group to move to the right. “Whee,” he whistled, trying to make another group speed up.

By now he knew every camel, by sight, by name, and by toe mark. And in the darkness he began to sing to them, and to one camel in particular.

“Duwan!” Bashir beams at the memory of his childhood companion. It’s as if he’s talking about a favorite sister. “If you put such a famous name in your book I’m sure many in the Ogaden will buy it! Duwan means that the camel is ‘different’—in color, or taller, than its mother. So everyone loves this one—because it’s the one who perseveres during difficult times, who produces more female babies, and more milk.” He could follow Duwan’s trail in the sand by tracking the large gap between her toes, and her left-curving nails.

There are plenty of traditional camel herders’ songs—indeed poetry is something of a Somali obsession. But the song Bashir sings to Duwan is his own composition, delivered with intense, quiet affection.

“It is you. It is you. The one. The camel who is always more powerful than others. A beautiful expensive woman—only you can equal her. Not sheep-es [he shares Tarzan’s habit with plurals], not goats.”

At first I don’t realize he’s singing. His talking voice slides into something lilting and tender, a grin spreads up to his eyes, and I find myself smiling too, as if we’re sharing some happy secret, while he translates the next verse of the song.

“Sheep and goat-es died for drought and famine. It is you—come, elder one who is still alive. It is you who produce milk and meat. It is you, the most expensive one. It is you who allows me to survive.”

“Colokolo…” Bashir abruptly changes his voice to make the noise of a wooden bell. “Duwan had a bell, because always she likes to stray, alone.”

But late that night, Bashir heard another sound. “Galubkolugh” is what I’ve written in my notebook, followed by an attempt to describe it as “a guttural sound, like someone swallowing tin pans.” It’s the sound, Bashir explains, of the same bell now being broken in the jaws of a lion.

“I heard it nearby. I had such fury. I can’t control. I heard galubkolugh, for lion destroying bell. Nearby, maybe about where that gate is.” He gestures to the university gate, thirty yards away from us. “And I ran toward the place to see what has happened. I can see the face of the lion. I have a small stick and small knife here.” He gestures to his belt. “And I can see the lion and Duwan, just like that. Her last seconds of breath.” His head flops to the side, as if his neck were caught in the lion’s mouth.

“There are five other lions standing there. The female, who killed Duwan, she removed some blood from her mouth toward me. Phooo.”

You mean she spits?

“Yes, she spits, so I ran away. There are some rock-es. I collect, then I start attacking them.” Bashir remembered that a solitary lion will often attack several camels, but a pack of six will almost always settle on just one, so he left them to eat Duwan, and rushed away to try to gather the rest of his herd.

“I tried! I spent the whole night like that. The sun comes up. Then the guy, about nine in the morning, he came to me. He looks terrible. I said, ‘Last night I escaped from being eaten myself by lion. Look—the blood on me. The rest of the camels … I don’t know.’

“You can imagine how I look. He didn’t beat me that time. He shouted at me, blaming me, like I’m weak. Not a clever boy. But the way I look—all my clothes are cut by the trees from walking that night.”

* * *

I NOTICE THAT BASHIR is getting quieter as we talk. His last mimicry—a howaaahoooaa sound he used to make as an alarm call to the camels—is almost a whisper, followed by an embarrassed glance around the lunchtime crowd now filling the university terrace.

These are not easy times to be a Somali in South Africa. As we’re talking, there are xenophobic riots going on at the coast in Durban—provoked by the Zulu king, who told a crowd that foreigners “dirty our streets” and should pack their bags and leave. Before that, there were vigilante attacks and riots in Soweto, near Johannesburg. Bashir shows me a photo of a friend named Abdul in Durban, sent to his mobile phone over the weekend. I count twelve stitches on a gash stretching from the bridge of his nose to the corner of his left eye, and four more wounds on his forehead.

“I have lots of friends in Durban. It’s mostly black people who attack. They have this attitude.” And Bashir remembers sitting in a crowded minibus taxi here, listening to those around him complaining about immigrants. “We were seven Somali students on the bus—the others were talking in their language, but we understand. They are saying, ‘Oh, they are taking our places and the government is paying for them.’ But it’s not true. Maybe these people don’t know how to start a business. The majority of people here are peaceful, good. But there is no proper action by the government to stop such xenophobia by bad elements in the community.”

Bashir has been in South Africa for seven years now, but not as an asylum seeker. “I asked first for asylum. They rejected.” So he went back north, to Kenya, where he’d once been registered, as a teenager, having strolled across the long unpatrolled border from Somalia. His Kenyan passport shows he was born in Garissa, in the east of the country. Not true, of course, but logical. How else should a nomad behave when his worldview, dictated by rains and wells and horizons and family, clashes with the bureaucracy of borders, nation-states, and visas?

So Bashir took his Kenyan passport, applied to take a business course at Wits, and returned to South Africa on a study permit. He describes what must have been a long and difficult process with the breezy confidence of a man at ease in any country.

“We don’t feel like citizens of any government. Not of Ethiopia. Not even Somalia. I can go anywhere. I’ve experienced a lot of hardships, so I laugh and sleep well. No big stress. And I believe if worse happens to me, I can survive, no problem.

“People are always scared of the small things. Maybe my life [as a nomad] made me a bit harder. I don’t tell myself, ‘This is difficult, I can’t do.’ I don’t believe that. I have to try. My life is divided in two—half as nomad, half not. I can’t laugh at the small things like other people do. Ha! Lah! Sure I can laugh—but not at the small things, because I was between seven and ten when I considered myself as a mature, big man. My father, and the life there, taught me—you are a big man. All things taught me—do what big men do.”

And so within three months of arriving in South Africa, Bashir had started his own shop. “Some university students asked me, ‘How can you own a shop and you’ve only been here a few months?’ and I say, ‘I can get business anywhere. I believe if I got to New York I can start something quickly.’ We start in the countryside. Somalis—we’re connected. I went to a place called Duduza, outside Johannesburg. I start a shop, for 45,000 rand. After one year I sold it for 270,000 rand. Then I established another one in Pretoria. It’s quite risky. Thieves come to my shop more than three times. They put a gun to my head, but luckily I survived.”

Bashir and I meet up from time to time in Johannesburg, and I’m surprised to learn that he has a wife and child living in Morocco. He’s also got a BA in politics now. Sometimes we’re joined by other Somali friends, who tell their own nomad tales.

The city’s largest Somali neighborhood is called Mayfair, over the ridge from Wits and down beside the train tracks to the west of the city center. Bashir’s eyes light up on rumors that a fresh consignment of camel milk has just arrived. “Haha! I like so much! It never expires—you put in container, wait a month, and you can drink without protection. Maybe more salty when older.”

He reminisces about the food of his childhood—honey made not by bees but “more small insect-like. And roots, you scrape and dig into the earth, or you climb tree and find something like berries up there to eat.”

He describes the squabbles over muddy watering holes, and women, and the ways in which elders would settle disputes between different families. One fight, which began when young men at a well slapped an older woman, ended in a gunfight and a fine of nine camels.

The most precious watering holes would often be elaborately divided, like a pie, with a slice for each family and their camels. During a drought, a fight began when one of Bashir’s camels wandered over to drink from the wrong side of a watering hole.

“My older brother took a gun from that guy and started slapping, beating, hitting him! I started with my stick to beat him! I was so young! Maybe seven.”

Bashir’s brother, Osman, won the fight, but then had to go into hiding in the bush until the elders could strike a deal to prevent the losers from coming to kill him. “Lots of guns at that time, lots of conflict over water, for bushes, trees. Such things happen. Some people love camels more than people. Ha!”

Bashir’s earliest memory is of an Ethiopian jet bombing his family’s encampment, looking to target Ogaden rebels who were fighting against the central government. “I was four years old. I was crying—Ahhhh! Ahhh! We run in the bushes.” He mimes the way his brother was holding his hand as they ran, how his aunt was hit by shrapnel in the head, and then a few years later, how another brother was killed by a government militia, and how he’s just heard by phone that his brother Osman has been arrested for, allegedly, giving “one goat to Ogaden rebels. It’s like house arrest—he has some goats, some camel with him.”

Bashir insists he, himself, is “not a rebel, not political.” But the suburb of Mayfair is full of ethnic Somalis from the Ogaden plateau who campaign, plot, and argue over the best way forward for their region and whether it should remain part of Ethiopia, seek greater autonomy, or take its chances with a reemerging Somali state.

Bashir keeps talking, and I’m reminded of Yusuf and, to a lesser extent, of Tarzan, who both have similar skills as raconteurs. Then again, so do most other Somalis I’ve encountered over the years. It stands to reason. Nomads have little use for paper or the written word. In fact, there wasn’t even a Somali script until the 1970s.

In Somalia, you are, in ways both casual and significant, what you say you are. And there’s another lesson I take from Bashir’s anecdotes—a fundamental truth that helped shape his childhood and shaped the country, too. When trouble comes, you look out for your camels, your family, your clan. And you fight.

* * *

“ALL I REMEMBER, VIVIDLY, is being naked.” It was 1960, or maybe 1961, and Yusuf was probably turning five, and Tarzan seven. A particularly severe drought had forced the family to leave its grazing lands and cross to the west bank of the Shabelle River, and the outskirts of the town of Prohibition. Their father, Ahmed, was sick.

“He was weakened by famine, but people said he had flu,” Yusuf says.

He can’t be sure what are his own memories of those days, and what his brother Muse has since filled in for him. But one day Ahmed accompanied his sons to bathe in the river near Prohibition, to watch over them, because of the crocodiles. Ahmed was already an old man, and his tall frame was stooped. “He was in his late sixties if not early seventies. In that area, that’s old.”

“Father died. He died a natural death. It was difficult at that time,” is the way Tarzan describes what happened next.

It’s a curt epitaph, and I’m left wondering whether it’s just because Tarzan remembers so little, or whether it is all wrapped up with what happens soon afterward.

Muse was just three at the time, but he’s since told Yusuf that he remembers the scene. Their father’s body was taken to a patch of ground, designated as a cemetery, outside Prohibition. There were rough pieces of stone to mark other graves, and no writing. “Most people don’t read or write,” Yusuf explains. Ahmed’s long, wizened body was laid out on a stretch of woven straw and washed for burial, then wrapped up in a length of cloth.

“He’s supposed to be covered with a sheet for burial. But they didn’t have enough clothes to cover him. Either because he was too tall, or because they didn’t have enough…” For once, Yusuf’s steady voice trails off. He means the family didn’t have enough money. Muse’s memory has become his—the image of his father’s feet sticking out, awkwardly and humiliatingly, from the end of his burial sheet, as he’s lowered into a shallow, sandy grave.

Then things got much harder. Without a husband to help look after the animals and five young children, and with the drought tightening its grip, Ahmed’s widow Habeba was struggling.

Yusuf remembers his mother as “the kindest, nicest person.”

Tarzan, once again, has a more curt assessment. “She could not cope. You have to get water, put water to camel, so a woman cannot do that. So she cannot look after herself and five children.”

Reading his words back now, I am immediately reminded of another young woman from approximately the same era, region, and background.

Ebla was an eighteen-year-old orphan who had the same instinct as Habeba, to run away from her nomadic encampment to avoid an arranged marriage. She is a fictional character—the subject of From a Crooked Rib, Nuruddin Farah’s first novel.

Ebla, he writes, “wanted to fly away from the dependence on the seasons, the seasons which determine the life or death of the nomads. And she wanted to fly away from the squabbles over water, squabbles caused by the lack of water, which meant that the season was bad. She wanted to go away from the duty of women.… Even a moron-male cost twice as much as two women in terms of blood-compensation. As many as twenty or thirty camels are allotted to each son.… ‘Maybe God prefers men to women,’ she told herself” (From a Crooked Rib, Penguin Classics, 1970, 13).

But escape was no longer an option for Habeba. She had five boys to care for, and she moved the family under a bridge outside Prohibition, camping on the dry riverbed, the herd left to fend for itself.

“We were starving. It was terrible. All I remember is that bridge,” says Yusuf.

“We all were sick. All crying. I remember it was near a river. So mosquitoes. All of us had malaria,” says Tarzan.

At which point a message was sent to Mogadishu for help. The details have been forgotten, but it cannot have been easy to arrange. Someone—a passer-by perhaps, or a friend—must have agreed to walk to the nearest telegraph office, in the Somali border town of Beledweyne, about 50 miles downriver. It’s the same town Ebla first ran away to in Nuruddin’s book. From there, someone in the Nur family’s network, who was working for the city council, sent a telegram to Mogadishu, and to a woman both Tarzan and Yusuf describe as an aunt, although in fact she was their father’s cousin.

Her name was Fatima, but everyone knew her as Guura. It’s a nickname given to a child born “on the move,” but Yusuf, as usual, elaborates. “It refers to someone traveling at night, usually with stealth and perhaps even during hostilities.”

Guura, by all accounts, took some time to respond. Her son, Mohamed, was an ambitious, well-read student who would later become a diplomat and have his photo taken with President John F. Kennedy. Eventually he persuaded her to take a bus to Beledweyne, and then to hitch a ride on a truck crossing the border to Prohibition, and “see what she could do.”

It’s possible that what happened next was meant as a temporary solution—a brief respite for a family in a desperate state. But it didn’t work out like that.

Guura made the long journey from Mogadishu and arrived to find Habeba in the shade on the riverbed, with all five boys, filthy and naked, beside her.

A decision was quickly made that two of the children would return with Guura to Mogadishu. Habeba could perhaps cope with the other three. But which children to take? The oldest two?

As the second child, Tarzan—or Mohamud as he was still known—was immediately selected. But when Guura suggested taking the oldest boy, Mohamed, as well, Habeba objected.

“Not having any daughters, my mother depended on Mohamed for her biggest help. So as fate would have it, she said she wanted to keep him,” says Yusuf. As the third born, he found himself chosen instead.

“So that’s how I ended up coming along, and getting educated. Otherwise I would have ended up as a camel boy. Now I don’t remember anything about my father or mother. Strange.”

Tarzan is more blunt. “I was very lucky for my father to die. Believe me. It was a miracle Allah sent to us. Had my father been alive I could end up as a camel herder.”

Guura looked at her two new charges. Neither had ever worn clothes in their lives, let alone been in a vehicle. “Let’s put a cloth around your waist before we leave,” she told them.

If there were farewells, neither boy can recall them. They walked with their aunt to the main road, then clambered down into another dry riverbed to find shade under the bridge, and waited for a passing truck heading south, from central Ethiopia toward Mogadishu.

Over the years I push both of them for more details. Yusuf is adamant. “I have no recollections at all.” But Tarzan gives the impression of someone consciously shutting a door.

“I never went back. Believe me. Even when I grew up. Never.”