“Mogadishu’s bangin’, man!”

—HASSAN MOHAMED

Fisherman carrying shark, Mogadishu, 2015. COURTESY OF BECKY LIPSCOMBE

IT FELT GOOD TO BE bored.

I was sitting in the back corner of the mayor’s office, stifling a yawn and wallowing in the sheer ordinariness of what was going on around a long, varnished wooden table that took up almost the entire room.

Six men were squeezed along each side, talking, in turn, in measured tones. At the head, behind his own desk, which was pressed up tight against the top edge of the long table, like a rather cramped wedding banquet, sat Tarzan. He was wearing an open-necked pink shirt and seemed to have put on a little weight. He looked supremely relaxed.

“Just two hundred dollars?” he asked the men, with just a hint of incredulity. “Even the biggest companies, the telecom companies, they should pay the same?”

A gray-haired man coughed and explained that yes, that was “global practice,” that “everyone” did it like that. The others nodded. They were businessmen, representatives of Mogadishu’s Chamber of Commerce, and the topic under discussion was a plan to begin licensing the city’s businesses—a necessary step toward reviving a formal tax system that would, for the first time in two decades, involve giving money to the local administration rather than paying protection to the men with guns.

“We must collect taxes to build the nation,” said Tarzan, a touch pompously. I wondered whether he was talking, at least in part, for my benefit, offering up a sound bite for a wider audience.

“For now we depend on outside help, but with the business community’s support we can fund our own basic services,” he declared. More slow nods around the table.

Tarzan’s program manager, a relentlessly upbeat young returnee from Texas, Abdirashid Salah, had kindly offered to translate for me, whispering in my ear over the wheezing drone of the room’s solitary, ancient air conditioner. He’d left Mogadishu in 1992, finding his way to the United States via Kenya and South Africa.

I’d heard stories of official translators trying, patriotically, to clean up the language of the various thugs and warlords who sometimes gathered and swore and threatened around the mayor’s table. No topic was too small to trigger a row. On one occasion, the city’s sixteen district commissioners had all assembled for a meeting, only for three of them to break off into a fierce, seemingly dangerous squabble over the biscuits. There were not enough to go around.

Before the year was over, two of the Chamber of Commerce’s senior officials sitting at the table would be murdered, presumably by Al Shabab. But today was all smiles and humdrum negotiations. Abdirashid whispered something to me about a deal involving five different categories for licensing, and then he fell silent. I could tell he wasn’t leaving out any swear words; he was just trying to spare me the boring bits.

And it seemed to me, in that instant, that humdrum was a pretty good milestone for Mogadishu, a sign of progress and of something close to normality in a city that had once forgotten the meaning of the word.

Tarzan stood up wordlessly and disappeared behind a large curtain that appeared to lead into a separate office beside his desk. The conversation at the table stopped. He emerged a few minutes later and sat down again as if nothing had happened. He did the same thing several times over the next hour, and—although he later explained that he either went to pray, to discuss something with an aide, or to relieve himself—it struck me as an overtly theatrical flourish. It was the behavior of a man who was aware of the power he now exercised and was more than comfortable in displaying it.

The Chamber of Commerce delegation left. Next up was a group of women who wanted to organize another festival, to mark the first anniversary of Al Shabab’s withdrawal from the city.

“Agreed.”

“Next?”

At about noon, Tarzan went behind the curtain, returned almost instantly, and came over to greet me. We walked out together, through a tiny reception room packed with more officials and civilians clamoring for a few moments of the mayor’s time, past a middle-aged guard seated at the entrance to the building who was carefully rearranging a giant bandolier of bullets around his neck like an actress with a mink stole, and outside to Fanah, Tarzan’s cousin, who was standing in impenetrable silence, as usual, beside his car.

“I want you to meet a friend,” Tarzan said to me with a grin, as we got into the backseat.

* * *

WE SPED THROUGH THE narrow dirt lanes of Hamar Weyne with seven armed guards in the “technical” battlewagon ahead of us—one guard manning a huge anti-aircraft gun on a tripod, pointing over the driver’s cabin—and ten more in the pickup behind, a jumble of legs hanging over the sides.

“More guns these days?” I asked.

“We don’t want anyone to intimidate us,” Tarzan said with another big smile. He had recently begun carrying his own gun. A small black pistol.

“Belgian, I think,” he said.

Someone—presumably Al Shabab—had tried to blow up his car with a roadside bomb a few months earlier, but by chance he’d just been dropped off at home. The explosion was weak and had only lightly injured the driver. There also had been a separate hotel attack, again just after he’d left.

We turned a corner and passed a huge, whitewashed building.

“The mall,” said Tarzan. “It’s been unused for twenty-one years. We’re trying to rehabilitate it.”

He was talking fast now, pointing out old landmarks amid the rubble and confidently rattling off plans and projects. He pointed to the new drain covers by the side of a freshly tarmacked road and then gestured toward some new streetlights.

“This is a big change. Believe me.”

For months, Tarzan had been trying to bully local businesses into providing lighting for some of the city’s dark, dangerous roads in order to improve security and lengthen trading hours. But he wasn’t having much success. Now, though, Norway and Britain were funding a new scheme to put solar-powered lights along all of Mogadishu’s main arteries. And the first results were already transformational.

Tarzan clearing garbage, Mogadishu, 2011. COURTESY OF ABDIRASHID SALAH

Some nights, the main road from K4 to the parliament would be clogged with children, from end to end, in a succession of floodlit, impromptu, five-a-side football matches. Girls as well as boys. It was a message to Al Shabab—we are taking our city back. Mogadishu had seen nothing like it since the time of Siad Barre, and the spectacle was enough to make some people weep. This was what Tarzan meant when he talked about changing people’s mentality, repairing the psychological damage of war.

It wasn’t just the European donors who had taken a shine to Tarzan. The Americans, the Turks, everyone seemed to be knocking on the mayor’s door these days, now that the city was united under one administration.

He offered something tangible. Or at least he seemed to. Instead of red tape and backhanders, Tarzan, with his boundless energy, offered an open door and quick results.

And speed was essential.

A more experienced administrator might have taken things slowly, building up the city’s institutional capacity, strengthening the bureaucracy—and indeed there would be a time for that in the years ahead. But Tarzan seemed gripped by a furious sense of urgency, by the need to behave, you could say, like an army surgeon rather than a physiotherapist.

“Time is running out. We have to build people’s confidence. We have to provide services. The day people ask, ‘What’s the difference between the government and Al Shabab?’ That day we are dead.”

And so Tarzan let the Norwegians arrange the streetlights. He let the Turks fix the roads. He bypassed what he still considered the hopelessly inept bureaucracy of the UN. He was a facilitator, a catalyst, a hustler, a symbol. And if that meant he shamelessly took the credit for other people’s work and investment, so much the better. After all, people needed to believe in him. That was part of the plan.

* * *

TARZAN WAS BUSY SCOFFING at several government ministers—at their pathetic work ethic, at their long lunch breaks, at the pitiful way they begged foreign donors for minor items like office furniture and computers—when the convoy swung to the right, crossed the open patch of ground where the mayor’s Peace Festival had come under fire a year and a half earlier, and stopped sharply in front of a small, freshly painted building opposite the national theater.

“This is my friend’s restaurant,” Tarzan said.

It didn’t look like much at first. The Village restaurant was more like a shack, squeezed onto a patch of ground between the main road and a large, refurbished office block, with an open kitchen beneath a bright green corrugated roof and a dozen plastic tables on the curb outside.

I’d heard the place was more popular toward dusk, when the ocean breeze began nudging aside the day’s heat. But today a dozen men and a handful of women were sitting at tables in the shade of a big tree, sipping cappuccinos and waiting for lunch to arrive.

Ahmed Jama walked out from his kitchen and ushered us toward a table. He was a bald, scrawny forty-six-year-old, with a beak-like nose and an earnest, gentle manner. His politeness seemed like a rebuke, or a challenge, to the city around him. He reminded me of the British-Somali athlete Mo Farah, who was poised to win the 5,000 meters at the 2012 London Olympics a couple of days later.

“Tea, coffee, some lunch? We got barbequed shark, some lovely stews, grilled lamb, spaghetti?” Ahmed spoke quietly, with a thick London accent.

I noticed some fresh-looking scars and burn marks on his face. He followed my eyes and gestured with a nod, across the road, toward the refurbished national theater. Five months earlier he’d attended a ceremony inside. A woman sitting a few rows behind him had detonated a bomb strapped around her waist. Ten people were killed, including Wiish, the basketball referee who had objected so strongly to Oscar Robertson’s dribbling style. Al Shabab was quick to claim responsibility.

“If I’m killed, then I’m killed,” Ahmed said with a shrug. I was beginning to see why he and Tarzan were friends.

Ahmed Jama, Mogadishu, 2013. COURTESY OF XAN RICE

Ahmed also came from a poor family and abandoned Mogadishu to find work in the 1980s, before Somalia collapsed. He went to Kenya, Uganda, Sudan, Tanzania, and finally—after saving enough money to buy an air ticket and a false passport—to London. He was given temporary residency in the U.K., got married, stumbled into cooking almost by accident, trained as a chef, and by 2006 had his own Somali restaurant in Hammersmith, catering to an enthusiastic diaspora still eager for a taste of home.

“But then I said to myself, ‘One person can change something. I can do something for Somalia.’ So I decide to come back here, with my heart, and a clean mind. To be a man of hope.”

He left his wife and three young children and flew back to Mogadishu. It was a bold, bizarre, and, to my mind, typically Somali decision. Another nomad move. The sort of drastic uprooting that only someone who had thrown his luck to the wind before seemed likely to attempt. And this was in 2008, long before the famine, before Tarzan’s return, before Al Shabab had even pushed out the Ethiopian army.

Ahmed started with a coffee shop. Then a restaurant. Then a small hotel. Soon he added another, bigger place called Village Sports, blasting out music and football matches within earshot of Al Shabab’s frontline and catering to the growing crowd of diaspora Somalis who were starting to venture back to Mogadishu, testing the water at first, seeing if it was worth coming back for good. Before long, Ahmed was employing more than a hundred people.

“I miss London. I miss my friends. I miss Arsenal. We live by Queens Park Rangers in White City. But I’m an Arsenal fan,” he told me, sitting at our table now. But he had no plans to leave Mogadishu. He and Tarzan were gripped by the same sense of mission, of pride, and of purpose.

“We’re not coming back here for the money. Me, the mayor, we’re looking to change the city, to change the mentality, to show people how we lived abroad as Somalis—not as different clans. To show them a different way of life,” Ahmed said, his eyes holding mine.

The flip side of that plan was to convince other Somalis in the diaspora to follow his example. To show them that Mogadishu was on the road to recovery.

“There’s a lot of work to be done here. You need patience. Rome wasn’t built in a day,” Ahmed said.

“So it’s time the diaspora came home?”

“Absolutely. And it’s happening already. The flights from London are full! Soon it’s going to be like Shepherds Bush here,” he insisted.

He was talking about the wealthier diaspora, mostly making brief visits from Europe and America. But before long, tens of thousands of poorer Somalis would weigh up the odds and start making the long trek home from their crowded refugee camps in Kenya.

Unlike Tarzan, Ahmed chose not to have any personal security. There were guards outside his restaurants, and the gate to Village Sports already bore the scars of a couple of suicide attacks. He admitted to paying bribes—essentially protection money—to the government security and intelligence services. But he drove himself around the city on his own, unarmed.

“I’m not a politician. I don’t have anything against anyone. So even if I see the Shabab, I’ll try to show them a different way—to show them how human beings can live together.”

He was busy training new chefs and trying to encourage his guests to eat more seafood. Somalis preferred camel or goat meat, but the old fish market had just been reopened down by the lighthouse, and the small boats were bringing in an impressive catch. I went down there one afternoon—the fishermen tended to come ashore around 3 p.m.—and watched, half-hypnotized, as one man carried a large hammerhead shark up from the beach on his head, then threw it down on the dark concrete floor of the market. Three scrawny kittens, and a swarm of flies, immediately gathered by the spreading pool of blood.

A couple of days later, I met Ahmed and his family at Village Sports. He’d finally persuaded his wife, Amina, to come over from London with their boys.

“She’s shy,” Ahmed said when Amina hurried away. “And she’s never been keen about this. She’s still not keen. I just kept pushing her, asking her to give me more time. Still, she’s here now.”

A few weeks later, the Village restaurant was attacked. I was back in Johannesburg and called Ahmed the following morning.

“How are you?” he asked. Even now, he couldn’t shake off that instinctive politeness.

“Me? Fine. But you? What happened?”

“There were two suiciders,” he said quietly. “It was a bit unexpected.”

Ahmed had left the restaurant perhaps ten minutes before it all happened—at around quarter past six the night before. He had some errands to run. One attacker began shooting at the diners outside. As usual, there was a mixed crowd of politicians, journalists, and businessmen sitting at tables by the roadside. The other gunman then ran inside, behind the kitchen, toward a smaller dining area, where he threw a grenade and detonated his suicide belt.

“Five of my staff have been killed. But ask me more questions. It’s OK.”

In all, fourteen people were killed. Al Shabab claimed responsibility. But perhaps the most remarkable thing about the attack was the way Ahmed responded. The idea of quitting never appeared to have crossed his mind. Almost immediately, he and his colleagues began clearing up the mess.

It was straightforward enough outside, but inside the restaurant, the suicide bomber’s remains now coated the walls and ceiling. The team used shovels and trowels, and eventually brooms. Then they began to repaint. It took three, four, sometimes five coats to cover up the blood. A little over a fortnight later, the Village restaurant reopened. Tarzan was there to mark the occasion.

* * *

IT SAYS A LOT about Mogadishu that Shamis can’t quite remember if she heard about that particular attack. After a while the individual blasts and incidents all seemed to blur into each other.

But the important thing was that Shamis had finally come back to Mogadishu to join Tarzan. She’d tried once before, toward the end of 2011, staying at the Nasa Hablod 2 hotel with him. But she’d hated it. One evening, two mortars had exploded in the courtyard, and the next day she told Tarzan that she wanted “to go home.” She meant to London. Her visit had lasted five days.

This time, Tarzan found a house to rent. It was just behind the national theater, up the slope toward the State House, and within earshot of the Village restaurant. There was a big, well-guarded barrier at the bottom of the road, and another at the entrance to their cul-de-sac. They were within the security bubble of the presidential compound—often breached but still much safer than any other options around the city.

Shamis was not back for good. That was never the plan—she had far too many ties to London. All six children were now grown up, but they lived close by, and their lives were still closely entwined.

Abdullahi was finishing his degree and living in the family flat. Ayan had her two daughters to care for and was about to meet and marry an African American truck driver on a visit to Baltimore.

“A lot of people assumed that my dad wouldn’t allow it,” she tells me with a grin. “And I was like, ‘Er, he’s not going to care as long as he’s a good person—a Muslim, and a good person.’ A lot of Somalis are not like that. Somalis tend to be racist within themselves, so marrying a complete outsider…”

“Yeah,” Abdullahi chips in, “it’s like they won’t even marry a Somali from a different tribe. I wouldn’t care—any race. It doesn’t even have to be a Somali girl.”

Through different academic routes, Ayan, Mimi, and Muna had all ended up finding full-time jobs at the nearby Whittington Hospital, Ayan and Mimi in customer care and Muna as a health advisor. After struggling to make ends meet as a fitness coach and community worker, Mohamed was looking to study physiotherapy at a university.

So Shamis was in no mood to abandon Queens Crescent altogether. She would stay in Mogadishu for a few months at a time. That was the agreement.

She talks of it now as a sense of duty. And love. She wanted to be with her husband. But for Tarzan, I wonder if there was an element of politics in it, too. He didn’t want to be seen as another diaspora dilettante with one foot in London and a British passport in his back pocket, ready to scarper when the going got tough. Bringing his wife to live in Mogadishu with him was a sign of commitment. They were lucky the children were already grown up.

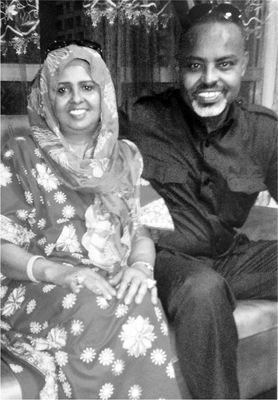

Shamis and Tarzan. COURTESY OF THE NUR FAMILY

But Mogadishu held few attractions for Shamis. The shared dangers and drama inherent in everyday life in the city brought them closer together. But they began to argue, too, about how little time he spent with her, about how long he was going to keep doing this; after all, they’d both worked hard for years. Weren’t they supposed to be thinking about drifting toward retirement now? Shamis asked. Why didn’t he warn her he wanted to be a politician before they married?

She could hardly even leave the house.

“It’s not easy. I miss the freedom. I miss taking the bus, going for a walk. So it’s tough. Really tough.”

The murder of Tarzan’s friend, the interior minister, Abdishakur, by his own young niece still weighed heavily on people’s minds. One morning soon after she’d arrived, Shamis found herself sitting at an aunt’s house and being overwhelmed with panic. Another guest had just arrived. It was a man wearing a thick beard with a shawl over his head.

“Is he Al Shabab?” Shamis hissed when he left the room for a moment.

“Of course not.”

“Then why is he dressing like that? Maybe he’s gone out to tell someone that I’m here. Maybe they’ll kill me when I leave.”

Nothing of the sort happened. But still, it was almost impossible not to become paranoid. Most days she just stayed in their house, preparing food and trying not to pick up the phone every few minutes to call Tarzan and check that he was safe.

* * *

I CAUGHT UP WITH Shamis again, back in London on one of her trips home. It was a dark winter’s evening and she was in the flat, bustling around nervously as she prepared to come out to Somalia again. Her granddaughters—Ayan’s children, eight-year-old Malia and five-year-old Maya—were in the sitting room watching Scooby-Doo. Her sons, Abdullahi and Mohamed, popped in later to say goodbye and started teasing Shamis about Tarzan, speculating about whether he might take a second wife in Mogadishu.

“He wouldn’t dare,” Shamis laughed. But she had heard rumors that some families were making inquiries, maybe even nudging younger nieces and sisters forward.

“If he takes another, I will leave. He knows that. I’m not going to be a second wife. Why should I? All these years we live together and he goes and takes another, a small girl? Those people are crazy. Did I do a bad thing? No. And he’s not like that, anyway.”

“It’s not right. I don’t want him to,” said Abdullahi, turning serious, too.

Mohamed, the family provocateur, shrugged. “It’s human nature. But the truth is that Dad’s quite shy. And he’s too old now.”

On my way out, Shamis came to the top of the stairs in the apartment block to say goodbye. It was starting to drizzle on the street outside. She told me she’d lost eleven pounds in the last few weeks. She seemed suddenly coy, like that young girl holding hands with Tarzan in a café in Mogadishu all those years ago.

“I want to be an hourglass figure before I go back to him,” she said with a small smile, her hands drifting self-consciously toward her hips.

By then, their oldest son, Ahmed, had already gone out to live in Mogadishu, to make a new start after his divorce. He remarried a local woman almost immediately. Before long, like other diaspora families who shrugged aside the risks in order to reunite with their far-flung relatives, Shamis was making plans to bring Abdullahi and the granddaughters out to visit the following summer.

“It was really fun!” Malia told me in London after that first trip. It was another cold afternoon, and she and Maya were skipping back from school to their granny’s flat for tea.

“We went to the beach some days. Lido beach. It’s beautiful! We got to collect seashells from the sand.” The girls wandered off into the sitting room to watch The Great British Bake Off.

“They like it in Mogadishu because they have space,” Shamis said. “They live in a small flat here in London, and their downstairs neighbor is always shouting at them to be quiet.”

Abdullahi, now a twenty-three-year-old unemployed graduate, found the whole experience of visiting Somalia much more uncomfortable. Everything seemed to amplify his sense of not belonging. Even the language. He spoke Somali, but it was rusty, so he’d get the sentence structure wrong—saying “I’m watching TV,” when in Somali it should be “TV I’m watching.”

He got spooked the very first time he went out in the car in Mogadishu, with guards, to get an ice cream. Another car was following them and they had to race to get away from it. Luckily nothing happened. But still. A few days later, he was at his parents’ house, alone with his nieces, when Al Shabab launched a series of attacks around the city. It sounded like someone was driving down the road throwing out bombs.

Abdullahi tried to talk to guys his age in the neighborhood. But it was like they were on a different wavelength. One day a local man in his late twenties was killed by accident. His friend hadn’t realized there was a bullet in the chamber of the gun he was fooling around with. Twenty minutes after it happened, Abdullahi ventured outside.

“Wasn’t that your friend?” he asked a group of men standing on the street near the spot where it had happened. The police had just come to take away the body, plus the guy who pulled the trigger. The others were goofing around, laughing, joking. Sure they were upset, they said. But so what? Stuff like that just happens here.

Abdullahi didn’t leave the house for a week after that. “It was crazy. Crazy. I swear to God I just slept all day.” He felt like he couldn’t trust anyone at all—especially those who’d never been abroad. And the stuff about the interior minister’s niece—people were still “freaking out” about that.

Toward the end of the holiday, Abdullahi accompanied Tarzan to Villa Somalia for Friday prayers. There was a big crowd. The president was there, and Abdullahi felt both proud of his dad and a little out of his depth. He stood at the back, declining to join his father in his usual prayer spot.

It was only when people started to get up to leave that Abdullahi finally found space on the floor to begin his own prayers. He was standing, focused, about to kneel down, and he began saying “Allahu Akb…”

At which point it felt like the entire room jumped on top of him. It was the president’s bodyguards. They were all over him. Pinning his arms. One guy had his hand on Abdullahi’s throat. And Abdullahi was fighting back. He found himself screaming and swearing at the men—in English, which seemed embarrassing in retrospect. “Fuck you. Fuck you.” Stuff like that.

Finally someone who knew him, one of Tarzan’s friends, pushed his way to the center of the group and told the guards who Abdullahi was.

“He looks like Al Shabab,” one of the guards retorted. “Look at the way he’s dressed. Jeans. And he’s skinny. And that haircut—short at the sides, long on top—that’s how Al Shabab cut their hair.”

Abdullahi left Mogadishu soon after that.

A few months later, back in London, he told me about the incident. He could laugh about it now. But what was really interesting was his mother’s reaction.

“They nearly killed him that day!” Shamis said, as if it were a big joke.

At first it reminded me of the way many Africans use laughter to cover either fear or embarrassment. But then she started turning it all against Abdullahi, chiding him for staying in the house the whole time in Mogadishu. “He didn’t go out! Not at all. He was not brave.” And it got more pointed. Shamis compared him to her oldest son, Ahmed, the one they nicknamed “Kill Me” for his casual approach to danger.

“Ahmed is very brave. Like his dad,” she said.

“I don’t call it brave. I call it stupid,” Abdullahi shot back.

It was a strange, awkward moment. Shamis seemed to be behaving out of character. She made me think of some caricature of a patriotic mother, grimly sending her sons out to battle and ridiculing any sign of weakness.

But that was unfair.

I was sitting at a table in the Sir Robert Peel pub, on the corner of Queens Crescent, typing up my notes on a laptop a few hours later, when I remembered something else Shamis had said to me back in Mogadishu. She was talking about the sense of being marooned between two identities, about how she felt like a second-class citizen in both the U.K. and Somalia. Here in London people still picked at her accent, even other immigrants did—she’d had a row with an Egyptian man in the market just the other day. And back in Mogadishu, she was marked out as “diaspora,” as someone with a foreign passport.

And I realized that sense of ambivalence must be how she felt about courage, too.

On the one hand, she had to believe in what Tarzan was doing, in the risks he was taking in Mogadishu. And if her sons were prepared to share those risks, then maybe that would help to shore up her own conviction that it was all worthwhile. On the other hand, she was a protective mother of six Londoners, of children who had never even heard a gunshot, had forgotten most of their parent’s language, and barely understood Tarzan and Shamis’s commitment to their messed-up homeland.

No wonder Shamis sometimes swerved erratically from one extreme to the other.

* * *

BY NOW, THE MOOD in Mogadishu was definitely changing. The city was still dangerous, but Tarzan’s message of optimism was starting to catch on. He couldn’t take all the credit—much as he may have wanted to—but his name was on the lips of many members of the Somali diaspora as they booked their air tickets and began to flood back to take a look.

Some came to visit relatives, or reclaim a property, or to straighten out a troublesome teenager who didn’t appreciate how lucky he was living in Toronto, Columbus, Minneapolis, San Diego, Seattle, Stockholm, Nairobi, Bristol, Birmingham, or wherever. Sometimes it was to help—doctors and teachers looking to share the skills they’d learned abroad. And sometimes, it was just to see if there was money to be made in a city on the upswing.

I met dozens of them over the next year or two. The women, often young, were particularly bold and inspiring. An indignant London student who was chased out of Mogadishu within days by an uncle who thought she’d come back to steal his clan’s seat in parliament. An irrepressible human rights activist from Dublin who spent her days shaming and haranguing government ministers about their failure to tackle female genital mutilation and rape. A holidaying divorcée from rural North Dakota, eating fresh lobster by the beach and relishing the heat. A teenaged boy from Wembley who was so afraid of Al Shabab he couldn’t even say their name, but kept declaring, “Mogadishu’s bangin’, man!” An estate agent from the English city of Luton with grand plans for a compound of luxury villas in the dunes north of the city.

In fact the estate agent, a man nicknamed Martello, after the Italian for “hammer,” later emailed me a letter that his twelve-year-old son, Akram, had written to his teacher, back home in Luton, after spending the summer holiday with his father.

“Dear Ms Raffee,” he wrote, “Somalia is a very different place now. I went to the beach several times and play football with my friends. The threat and influence of Al Shabab is very minimal, although they are still out there. A new government is in place now, although it is very weak and broke. With my dad I met with the mayor of Mogadishu, who allowed me to sit on his chair in front of his senior officers even though he doesn’t allow anyone else to do so. He told everyone in the room that I will be a future mayor of this city. I hope you will come and visit us to see the beautiful beaches and the education system here. My dad will provide you with accommodation and security during your stay.”

The diaspora’s stubborn, defiant optimism seemed unshakeable.

* * *

ONE MORNING IN MAY 2013, I arranged to visit a grand, sturdy villa just a few blocks inland from the old lighthouse and the fish market. It was built by the Italians in 1919 and had recently been patched up and painted in the blue and white colors of the Somali flag. It looked wonderful and entirely out of context, surrounded by ruins, like a wedding cake in a butcher’s shop. I walked up the cracked marble steps, pushed open a huge wooden door, and entered a cool, dark atrium.

I was there to correct something.

Journalists tend to be drawn toward conflict in places like Somalia. It makes for the strongest headlines, the most dramatic stories, and easily the best pictures. Besides, it’s often just plain hard, and wrong, to ignore that sort of stuff. But after years of seeing their country labeled as a “failed state,” Somalis were getting tired of people like me focusing, exclusively it seemed, on the negatives. What about the “iceberg of normality,” that the foreign minister had told me about when I first met him and Tarzan in Villa Somalia three years earlier?

The Somali Central Bank was that iceberg. Or at least a symbol of it.

The building and its contents represented everything the outside world had ignored about the country for two decades—the ingenuity, the resilience, and the resourcefulness of a nation whose economy had somehow managed not only to weather the endless storms but even to thrive. It seemed impossible, but the statistics were beyond doubt. Without the constraints of a central government, the local economy was doing just fine. Somalia’s mobile phone networks were among the cheapest in the world. The power grid in Mogadishu was an eccentric monument to unfettered capitalism. The livestock trade was booming. Customary law and clan elders kept things more or less in check. In many spheres, Somalia was doing better than at least half the continent, fueled in part by a spectacularly steady, generous flow of cash from relatives abroad, who sent some $1.6 billion in remittances back home each year.

And the miracle that underpinned this improbable success story sat on long shelves, in clammy, musty piles, in a giant vault in the basement of Somalia’s central bank.

“Look how fragile they are,” said Abukar Dahir, picking up a bundle of faded, crumbling Somali banknotes.

“What’s the exchange rate?” I asked him.

“This morning it’s approximately 17,800 shillings to the dollar.”

Abukar Dahir outside Central Bank, Mogadishu, 2012. COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

Thirty years ago, Abukar’s father had been the head of the bank’s foreign exchange department. He died weeks before his son was born and two years before the family fled abroad. Five months ago, at the age of twenty-five, Abukar came back to Mogadishu from west London to take up a job as one of the bank’s senior policy advisors.

If Abukar’s name sounds familiar, it’s because I mentioned him at the start of this book. A few months after our first meeting at the bank, he found himself trapped along with Tarzan in Villa Somalia’s mosque during an Al Shabab attack.

We left the airless vault and headed back upstairs to the marble-floored lobby of the bank. Abukar was sporting a blue suit jacket, checked shirt, thick eyebrows, and Lenin-like goatee. He’d studied law in London and then moved into banking. But here he was, now, helping to rebuild a central bank from scratch and not even trying to hide his glee.

“I’m so proud. This is something that happens once in a hundred years,” he gushed in a voice that matched his youthful, gangly appearance.

The bank itself had closed down in 1991, along with everything else, and stayed shut for the next twenty years. But to the consternation of most economists, the Somali shilling persisted, like the bumblebee that had never been told its wings were too small to conform to the rules of aerodynamics.

“These are forgeries,” said Abukar, taking me over to the desk of an elderly gentleman, with bright orange hennaed hair, who was counting a pile of thousand-shilling notes.

“And yet, they’re legal. Or rather, they’re accepted by the public.”

No new, legal Somali banknotes had been issued since 1991. And because paper notes rip and disintegrate and get lost, you’d expect the currency to vanish almost entirely within a decade. Instead, on four separate occasions, different regional administrations and warlords had printed their own, forged notes.

“So this old one is genuine. But this one’s a fake,” Abukar said gleefully, picking up a note with a picture of a fisherman mending his net.

Rather than rejecting the forgeries, the Somali public simply nodded and went off to spend them in the market. What else were they to do in their surreal world, untethered from the usual rules? Sure, they used U.S. dollars now for bigger purchases, but the survival of the shilling reinforced Somalia’s sense of itself as something resilient and unbreakable.

Abukar was good company, sharp and eloquent. Having overcome an early bout of nerves when he nearly refused to get off the plane in Mogadishu, he now appeared wildly optimistic about the city’s future. When I asked him about security, he pushed back. “Sure, I’ve been scared here. But I’ve been scared in London, New York, Stockholm. Besides, there’s almost no crime here. Just Al Shabab. And there is a kind of beauty in all this rubble.”

I knew what he meant about the beauty. It was as if the city was coexisting with its history. A living museum. It had the effect of making you constantly imagine the future, too—of what these ruins would look like when they’d finally been restored.

Abukar led me upstairs to see the bank’s prized possession. In a glass case, in a locked room, sat a small computer. It was a brand new SWIFT machine—a precious link to the outside world, finally and officially reconnecting Somalia to the global banking payment network. Abukar was grinning again. The next priority, he declared, was to start tracking down the Somali state’s money, lost for a generation in forgotten bank accounts around the world when President Siad Barre’s government collapsed in 1991 and its foreign assets were frozen.

Like so many other members of the diaspora I’ve met, Abukar had led a disjointed life. He grew up in Sweden but moved to London when he was fifteen. A few years after that, his mother woke him up with a jolt in the middle of the night. They’d both agreed to the plan beforehand. They wanted to find out which was his first language—Swedish, Somali, or English.

Abukar blinked in surprise at his mother’s face and said, without thinking, “Blimey.”

In Mogadishu, it was fun trying to guess which Somalis had been living in which foreign countries, not just by their accents but by the habits they’d picked up. “We Somalis are adaptable. We’ve all been forced to reinvent ourselves,” Abukar told me.

It was almost like a new set of clans. The Americans are “a bit more outgoing, they like to push things harder. They’re not so interested in consensus.” But the Scandinavian Somalis are the opposite, “endlessly trying to bring everyone on board.” The British are somewhere in between.

Abukar had left his British Somali fiancée back in London. It was putting a lot of pressure on their relationship, and he wasn’t sure how long he’d be staying in Mogadishu. But for now, he was hooked. I saw him on subsequent visits, and before long he’d moved into a brand new flat just behind Ahmed Jama’s Village Sports restaurant. He had high-speed internet, a gang of friends, and weekend trips an hour down the coast to Ahmed’s latest venture—a small resort on a lovely, isolated cove called Jazeera beach.

I began to wonder if the strain would ever start to show.

Abukar was getting phone calls from Al Shabab. Usually they just threatened him. “I’ll slit your throat.” But sometimes the same people would call up a day later, and he’d end up having long chats with guys who sounded about his own age. One was called Ali. Another said his name had once been Michael. They had thick Cockney or Birmingham accents and wanted to talk about how they missed KFC and football.

“You get desensitized,” Abukar told me one evening, when I asked how he was coping. “It’s fascinating how humans can adapt to different circumstances.” Fascinating … The word seemed too cold. It sounded like he was trying to bottle it up, to build a mental wall between himself and the dangers around him. By now, he’d lost a number of friends and been caught up in four near-miss attacks, including a huge bomb blast on the airport road, immediately outside a hotel where he’d been meeting some American treasury officials.

“It’s amazing how different people react. Some freeze—the shock takes over.” But not Abukar. He felt he was starting to get used to it. After the windows shattered and the shock wave threw him off his feet, he barricaded the doors shut and helped his colleagues hide under a bed, telling them he feared that the militants were about to storm the hotel.

“Mentally, I’m very strong,” he insisted. “I feel I can manage it. It’s not boring here. And that adrenaline keeps you afloat.”

* * *

FROM TIME TO TIME, Tarzan left Mogadishu on official business. One of his earliest trips was to Casablanca for a gathering of mayors from the United States and the Arab world. A networking opportunity for rich cities and powerful leaders. When it was his turn to speak, Tarzan suggested that it was the duty of wealthier cities, like Chicago, Amman, and Riyadh, to lift up their poorer relations. He peered around the conference hall.

“Does anybody want to become Mogadishu’s sister city?” he asked.

No one raised a hand.

Tarzan laughs at the memory. “Not a single person! Ha!” But the moment clearly stung him. “Arabs—that’s usually their attitude. If you’re bigger or better than them, then they lick your arse. But if you’re poor, they step on your head.”

But London was different.

In 2012 Tarzan traveled to Britain as part of an official government delegation to attend a huge international conference specifically aimed at raising funds for Somalia and helping the government chart the path ahead. The following year, a second, even grander conference took place in London.

Both events came across as cheerfully chaotic and half-frantic scrambles—a mixture of pledges, pomposity, frank talk, and backroom bargaining. But the second conference, in particular, felt like a special moment for Somalia, almost like a coming-out party for a government that was finally reconnecting—like that SWIFT machine in Mogadishu’s central bank—with the outside world.

In terms of the pecking order, Tarzan was a rather peripheral figure, comprehensively outflanked by dozens of presidents, prime ministers, and so on. But toward the end of the event, there was a special gathering for Somali officials, and for the diaspora, in Westminster’s imposing, historic Great Hall, across the road from the Houses of Parliament.

Is it possible to pin down the precise high point of any politician’s career?

Tarzan walked into the Great Hall and up toward a podium framed by huge organ pipes. There must have been more than two thousand British Somalis packed inside the chamber, their bright dresses and flags coating the baroque interior like some dazzling wallpaper spreading up into the steep galleries and toward the vast, domed ceiling. Winston Churchill, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr., had all given speeches from the same spot.

No one seems sure of the exact size of Britain’s ethnic Somali population. But it’s grown to well over a quarter of a million. Most families retain strong links to Somalia, and some have begun venturing back—a foot in each country—although again, the numbers are hard to pin down. But there’s no doubt that Tarzan has played a pioneering role, testing the water and urging others to follow his lead, a heckling, inspiring, antagonizing figure.

As Tarzan came into view, the place erupted into a giant, collective roar of approval. Here he was. A London boy. Maybe even a Somali hero. A man who had helped people to believe in Mogadishu once again.

“Tarzan! Tarzan! Tarzan! Tarzan!” It was like a football crowd.

Tarzan grinned. How could he not? A year earlier, he’d attended a similar event in London and the same thing had happened. He knew he was a powerful public speaker—even his enemies conceded that. “I speak from my heart, and people can sense it,” he says. At one point, the year before, he’d begged the crowd to come back home to Mogadishu. Come back to the beach. Back to the Lido.

“Lido! Lido! Lido!” They went wild.

But this year was different. Somalia’s transitional government had officially been replaced by a new and marginally more representative body. His old ally Sheikh Sharif was no longer president, and the new man did not enjoy sharing a stage with Tarzan. His agitated expression and his aides had already made that very clear. So when someone introduced Tarzan as “our next president,” he wondered if he was being set up—if someone was trying to create more friction between him and the new president. It was not improbable.

Not that it stopped him from giving a speech. Instead of begging the crowd to come home to the Lido, this year he picked another beach—Jazeera—where Ahmed Jama’s new resort had opened.

“Jazeera! Jazeera! Jazeera!” The crowd lapped it up again.

But then Tarzan looked across at the president and his team, and realized he better keep it short. Somali politics were dangerous enough already. The British ambassador to Somalia, Matt Baugh, was sitting in the chamber, watching the drama unfold.

“I’ve never seen anyone get such a raucous reception,” he told me later. He’d come to know Tarzan in Mogadishu and sensed a politician of growing clout and shrewdness, someone who seemed able to reach out beyond clan.

“There’s no way that room was full of Tarzan’s own supporters. What I think they were seeing was a Somali who was fighting on behalf of other Somalis.”

The ambassador stopped for a moment, as if picturing the scene again.

“He was like a rock star.”