“Blow us a kiss! Look at us! Hey—Comrade Siad.”

—SAMIYA LEREW

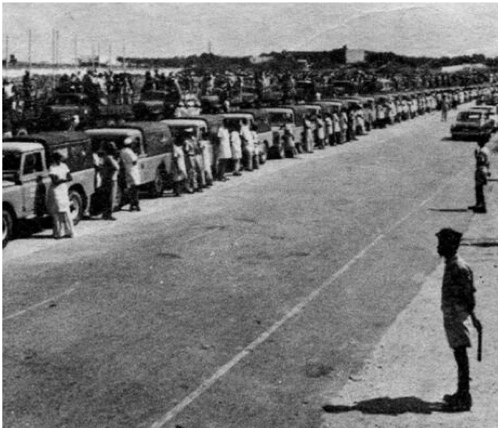

Mass literacy convoy leaving Mogadishu, circa 1974. POSTCARD COURTESY OF SAMIYA LEREW

IT FELT A BIT LIKE they were going to war. But in a fun sort of way, if that makes any sense.

Samiya sat in the back of a small, open truck, in a long, orderly convoy that trundled through the outskirts of Mogadishu. It was 1974, five years since she’d watched the crowds surge down the main road to welcome the military coup. She was seventeen now and sat with her feet on her luggage, her school friends squeezed in beside her. They were off to the countryside as part of a grand, unprecedented mission to drag their young nation out of ignorance.

The girls would normally raise their eyebrows sarcastically when it came to singing revolutionary songs. But today they all joined in, loudly and without irony, their grins bouncing around the truck.

“A revolution dawned in Somalia today.”

“Forward forever, backward never!”

“March on, our beloved leader!”

The convoy reached the southwestern edge of Mogadishu, the city ended abruptly, and their truck picked up speed as it slipped behind the dunes. Before long the singing eased off, and Samiya wrapped a shawl around her face and turned to face back toward home.

Beside her was a much taller girl, her head framed by a fashionably bouffant Afro hairstyle. At sixteen, Shamis was a year younger than Samiya and “pretty. A lot prettier than me.”

Shamis kept looking down to inspect her brand new sneakers. Like the others, she’d never been allowed to leave Mogadishu on her own before. The shopping and other preparations had been going on for weeks. Her aunt had bought her the sneakers to protect her against the snakes and other “biting things” that she’d been warned about in the countryside.

Shamis felt she knew a little more about rural life than the other girls. She wasn’t really a Beizani like them. Her father was a veterinarian who drove around rural Somalia in his own truck, with a big mosquito painted on the side. He was, inevitably, nicknamed “Dr. Mosquito,” or “Kaneeco” in Somali. He used to tell Shamis about the dangers of nomadic life—the crocodiles, hyenas, and malaria—and perhaps to show she wasn’t scared, and more likely to keep him close after the divorce and her mother’s death, she adopted his nickname, as one might put on a favorite sweater. Shamis Kaneeco.

A few days before they set off, the girls had gathered at a big parade ground in town, beside a brand new Soviet-built hospital, to listen to President Siad Barre tell them about their mission.

“The battle … has more value than anything you have known,” he declared in the tone of someone who did not expect to be doubted.

Five years after seizing power, the president could not be accused of idleness or a lack of ambition. There were regular “crash programs” designed to eradicate the very notion of clans and to reform the economy, all under the banner of “Scientific Socialism.” And with the president’s lofty goals came a growing need for tighter controls and louder propaganda. Visiting dignitaries—Uganda’s dictator, Idi Amin, for example—would be treated to a stadium filled with thousands of dancers performing tightly choreographed spectacles and wielding giant cards to spell out revolutionary slogans.

In hindsight, it’s easy to mock such Soviet-style extravaganzas. But Somalia was developing rapidly, and the president’s latest campaign had caught the public mood like no other.

Every school in the country was closed. Every Somali student aged fourteen years and above had been summoned to take part. More than thirty thousand people—teachers, volunteers, and officials—were poised to join. Somalia had never seen anything quite like it; nor, in terms of size and ambition, had the African continent. There was an overwhelming public thirst for education.

But there was a problem. For years Somalia had been wrestling with the fact that it had no written script. It was an oral culture, after all. People would write in Italian, or in Arabic. Or they would use one of those alphabets to come up with something that approximately resembled Somali words.

It wasn’t just awkward and unwieldy. It was humiliating.

Somali academics had been tinkering with new or hybrid alphabets; others insisted that anything less than a formal Arabic script would be “un-Islamic.” The arguments had been stewing for years. But the military government wanted a decision, and Samiya’s stepfather had been part of an official commission charged with analyzing all the options, picking a Somali script, and then drawing up plans for standardized spelling.

For such an acutely proud nation, the final decision was surprisingly pragmatic. New printing presses were expensive. Most existing presses used the Roman script. Therefore …

It’s easy to imagine Siad Barre’s large, impatient hand coming down on a desk somewhere, and brooking no further argument.

It may well have been among the best things he ever did for Somalia. And having taken the decision in favor of the Roman script, the next step was to spread the word.

* * *

ON THE DAY OF their departure, Samiya and Shamis found their designated truck in a huge column of vehicles on the roadside and clambered on board. Just before they were about to set off, they saw an open car drive by. The president was standing inside it, saluting his “troops” and exhorting them to take the “Somali Rural Literacy Campaign” to the farthest corners and the most isolated nomadic communities of the country. This was, he said, a cultural revolution that would break the old divisions of tribe, clan, and sect and unite Somalia. It was, in essence, a war against ignorance.

For a moment, teenaged instincts trumped revolutionary fervor.

“Blow us a kiss! Look at us! Hey—Comrade Siad,” the girls shouted out from the back of their truck. If the comrade heard them, he didn’t show it.

On time, and in unison, the convoy moved out of the city, heading southwest, on the main road toward Kenya. After a hundred kilometers, just outside another ancient port city, Merca, the girls’ truck turned right off the main road, heading inland. Half an hour later, it came to a stop in the middle of a small town.

It was called Qoryooley, the “place of firewood.” Although, of course, no one had ever written its name like that before. Now it was official—no more Arabic approximations, no clumsy Italian. Somalia had its own official script and spelling—no letters v, z, or p—and the girls were in Qoryooley to teach it to the uneducated masses.

They stayed one night at the local school and then headed out, deeper into the countryside, to their designated village, where they were to be billeted with local families. They had their luggage with them, a blanket each, and special teaching kits, which consisted of some chalk, pens, and books inside a wooden box that was crudely designed to fold out into a blackboard.

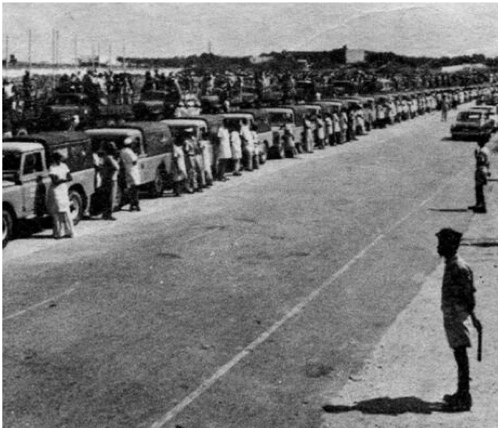

An old black-and-white photograph of their group has survived. Samiya dug it out and emailed it to me a few days earlier, and at first glance it seemed unremarkable. Seven figures in white shirts stare aimlessly at the camera, as if interrupted during the dullest of picnics. Behind them is a sun-bleached field, with some small trees in the distance.

But kneeling in the front row is a girl who seems to have wandered in from another era altogether. Her black curly hair cascades—yes, that’s the right word—down past her right shoulder. She’s wearing a tunic over an elegant long-sleeved shirt and the most enormous, glamorous sunglasses that reflect the sun, the horizon, and a smudge that must be the photographer.

Shamis (standing, second from right), Samiya (sitting on right), and friends, Qoryooley, 1974. COURTESY OF SAMIYA LEREW

The girl with the curls is Samiya, and as she breaks into a half pout, half smile, the figures around her suddenly seem to catch a glint of that same city swagger. It’s as though everyone in the picture has just woken up, and my eye flits from languidly folded arms, to another fashionable pair of sunglasses, to a hint of flared trousers, to something in Shamis’s casual poise.

They’re Beizani, of course. The offspring of Mogadishu’s cosmopolitan elite might have been roughing it on their very first adventure, but they could still flaunt their Italian clothes and urban sophistication.

I’m intrigued and call up Samiya to ask her what else defined the teenaged Beizani, besides clothes and attitude. The answer, she explains, lies in the relationship between Mogadishu’s elites and the former colonial power, Italy.

“Unlike the British and the French, the Italians integrated with the natives. You talked like them; you dressed like them; you thought like them; you were one of them!” Samiya remembers.

But surely the colonial Italians still considered themselves superior to the “natives…”

“Yes. But those who adopted their way of living were superiors, too. So to be inferior is to be one of the ‘bush’ people.”

And of course it was that sharp social division, between urban and rural, rich and poor, that the language campaign was supposed to help break down.

The teaching began. For the next seven months, the girls held daily classes in the open air, with their blackboards suspended from the trees. In Mogadishu, they’d learned the basics of their new script. Now they taught not only the children but their parents, too. The adults, who’d cheered their arrival in the village, were earnest and appreciative from the very start and would gather around the Beizani in the afternoons, seated on small stools in the shade.

“I was snooty,” Samiya admits with a small grin. But Shamis did not feel so out of place and seemed to have the knack for teaching. With her, the new script “flowed like water. She would laugh and chat with them in a way I couldn’t.”

At night, the girls slept, like everyone else, in small mud houses. Sometimes a calf would be brought in to share the floor.

“Not a tent. Not a proper house. They make their own…” Shamis hunts for the right word. “I don’t know how you call it in English. Igloo? Igloo! That’s it!”

The rains had been failing for some time. There was nothing particularly unusual about that in Somalia. But toward the end of 1974, the girls noticed that the nearby Shabelle River had dried out completely. Samiya’s mother, visiting them from Mogadishu, shared some worrying news she’d picked up from the radio station where she still worked. It was the worst drought in living memory, a national crisis that would come to be known as “the long-tailed drought.”

The villagers knew what to do. The girls watched them as they dug deep holes in the riverbed to find water. They built underground grain stores for their corn to see them through the hardest times. They were short of cash, but no one was starving.

For the nomads, this drought was harder to fight. Their camels, goats, and cattle died. Without them, they were broke and desperate.

The government, supported by the Soviet Union, reacted swiftly. The literacy campaign was not entirely abandoned, but a new and even bigger nationwide mobilization took place. Many students found themselves reassigned to huge government relief camps, which were quickly set up for the nomads in more fertile areas. Before long, a quarter of a million people were being looked after in the camps.

In the years ahead, that huge displacement of people would create new clan and ethnic tensions, with the haughty nomads bristling at the idea that they should till the land like mere farmers. But for now the government’s reaction to the drought was rightly deemed a success. Some eighteen thousand people died, but that was a small figure compared with neighboring Ethiopia, where famine was pushing the country toward open rebellion.

History has not been kind to President Siad Barre. He was a coup plotter, a dictator, and a warmonger. But 1974 marked a genuine high point. He’d steered Somalia away from famine, and by the time his literacy campaign had finally come to an end, the number of Somalis who could read and write had risen from under 10 percent to around 50 percent. It was an achievement that other postcolonial leaders around the continent could only watch with envy.

In their village, Shamis and Samiya continued to teach. They made a few friends, learned a great deal about ploughing, weaving, poverty—“an alien world to us”—and sometimes they got bored. A few months before they were due to return to Mogadishu, Shamis tried to sneak away for a night in Merca. She hitched a ride and went to see a cousin in the town. But this was still a country where everyone seemed to know everyone. Shamis was almost immediately spotted, detained, and, as punishment, promptly reallocated by the authorities to a new village, along with her blanket, blackboard, and snake-proof sneakers.

* * *

IT WAS A MONDAY morning, a week or so after the girls had come back to Mogadishu, having spent about eight months in the countryside. Shamis and Samiya sat near the back of the classroom in their yellow uniforms, waiting to see which awkward, gangly conscript—finished with his military training and now forced to do six months as a teacher’s assistant—would be assigned to their history class that term.

A muscular man of unremarkable height, in a white shirt and dark trousers, walked into the room and moved toward the blackboard. The class fell silent, chairs scraping back on the stone floor, as everyone stood up.

Shamis peered at the stranger as he picked up a piece of chalk and turned to face them. He was not handsome, that was for sure, she said to herself. But then she heard some of the boys nearby whisper in recognition. Some pronounced it “Tarsan.” After all, there was no z in their new script. Others said “Tarzan.”

Shamis was tall and reasonably athletic, but she had never been to a basketball match and had never seen this famous character before. She preferred the cinema. Still, she knew of Tarzan by reputation.

“A tough man. Very popular. Everybody knew him,” she says.

“If someone was getting bullied, he’d stand up and say, ‘No! This is wrong!’” That’s Samiya, who still talks about Tarzan with a mixture of awe, fear, and the giggly tones of a schoolgirl crush.

“He was a lion of a man,” Samiya gushes. “Not outstandingly good-looking, but firm. Always clean and smart. Shirt ironed. We were all skinny little shrimps, and he had this chunky sort of build. He walked past you and you were scared. Maybe because he has burningly beautiful eyes—that makes you not want to mess with him!”

Following his arrest for disrupting the quarterfinals of the basketball league championship, Tarzan went to jail, but only briefly. Once again, a senior figure—this time the head of the Somalita team—intervened and persuaded the authorities to drop the charges. They reluctantly agreed, and instead, Tarzan was banned for a year from playing or training with the team.

Instead, he taught the history of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the origins of the First World War to Shamis’s class. And after lessons, with more time on his hands because of the ban, he started coaching boys and girls in the school basketball club.

Shamis felt moved to sign up and found him approachable and straightforward—not overly flirty like some of the other conscripts. The school was perhaps 50 meters away from the home they would share nearly forty years later.

They began chatting and soon worked out that Shamis had almost certainly insulted Tarzan, a decade earlier, on the street outside her aunt’s house.

Every Thursday, before the coup, the police band marched around Mogadishu playing trumpets, drums, and trombones. It seemed to have the same impact on the city as an ice cream van’s jingle, and children would rush outside to watch the bandleader, left hand perched on hip, throwing his baton impossibly high into the air. And most weeks, trailing behind the band like extras from an Oliver Twist musical, came the orphan boys, doing their own swaggering imitations of the police.

“We used to run when we heard the orphans were coming,” says Shamis with a pretend shiver, remembering how everyone would taunt and fear the boys in equal measure. “We shouted ‘Orphan!’ at them.” And, no doubt, “Bastard!” too.

“That was me,” Tarzan confirms.

* * *

IT WAS NOT UNTIL well over a year after Tarzan and Shamis had met, properly, that Samiya found out that the two of them were now in a relationship. She’d left school by then and was taking typing classes at a small academy down the hill from Villa Somalia. Late one afternoon, she popped out to get a drink at the café across the road and stumbled upon her best friend sitting inside and holding Tarzan’s hand across the table.

Tarzan seemed mortified. “This lion of a man, suddenly holding hands with one of my girlfriends … a bit of a come-down? So he was shocked,” Samiya recalls.

“Now she’ll tell everyone,” Tarzan muttered.

“No. I know Samiya well. She won’t tell,” said Shamis, leaning across the table.

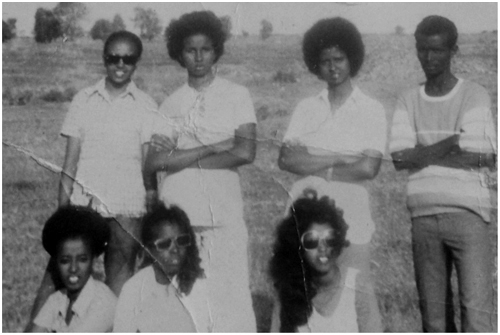

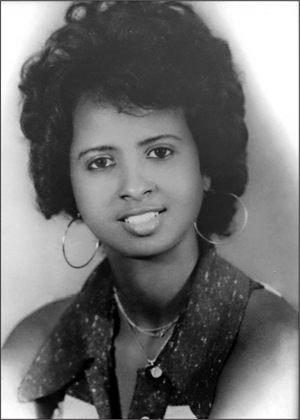

Shamis, Mogadishu, circa 1976. COURTESY OF SHAMIS NUR

But Samiya’s explanation for Tarzan’s awkwardness at being discovered—that his stature was somehow lessened by the relationship—doesn’t ring entirely true for me. If he was a lion, he was a penniless one, a troublemaker from a poor family and a tiny clan. Shamis, on the other hand, was a real catch.

* * *

SHAMIS WAS BORN IN a small rural town called El Buur in 1958, but her parents split when she was three years old. Divorce seems particularly common, and uncomplicated, in Somalia.

“If wives have a problem, they just say, ‘Divorce me,’ and you have to divorce,” says Shamis with a shrug.

Soon afterward, Shamis’s mother died in childbirth, and her father, “Mosquito” the vet, remarried. Then, like so many of the boys at the orphanage, Shamis found herself in an awkward position.

I can’t go into the details. Like her brother-in-law Yusuf, Shamis is uncomfortable talking about such delicate matters. Or rather, she talks at considerable length but then asks me not to repeat it because it will cause problems within the family.

“Did Yusuf talk to you about that?” she asks with an inquiring smile.

At the time, Shamis was her father’s only daughter. He approached his sister, who was living in Mogadishu, and asked if she would be willing to look after the girl. Shamis’s aunt appears to have been an even more formidable woman than Samiya’s mother—the radio and singing star. She immediately agreed to the arrangement, and it proved to be a happy one.

“My aunty said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll look after her.’ And she looked after me like her own daughter. Like more than that. She loved me and I loved her.”

The aunt’s name was Hawa Awale Abtidoon. Everyone knew her as “Little Hawa.” She wore high heels, smoked in the street, refused to wear a head covering of any sort, and possessed a deep, booming voice. She was the first Somali woman ever to campaign for a seat in parliament.

“People say, ‘She’s like a man,’” Shamis recalls, proudly. “She was a very tough lady.”

Hawa’s first husband was a wealthy businessman from Yemen. Her second was a bank manager. The family lived in a large villa near Samiya’s house, by the K4 roundabout, on the main road heading southwest out of the city. Shamis shared a room with one of her aunt’s five daughters and took a taxi to school each morning. On Fridays the whole family would head to the cinema, followed by dinner at an Italian restaurant and perhaps a stroll along the beachfront.

Tarzan, in other words, was a little out of his depth.

Nonetheless, it didn’t take too long for news of the relationship to spread. “We used to date normally,” says Shamis, by which she meant they began going to restaurants together, and to the cinema. She wore miniskirts. They both wore flares. They argued over which films to see. She loved the Hindi films. He refused to go and would take her instead to see the latest Italian releases at the Equatore. Before sunset, they would often fare una passeggiata, the Italian ritual of the leisurely evening stroll, which had long ago become a Mogadishu tradition, as enthusiastically practiced as the siesta.

Shamis would dress up for the occasion. High heels, billowing dresses made by local tailors copying Italian fashion, big earrings, and elaborate hairdos.

“She was slender. So pretty,” says Samiya with her usual enthusiasm.

When I ask Shamis if Tarzan was her first boyfriend, she starts to answer, blushes furiously, and tells me I’ll get her in trouble. “Tarzan was my first,” she finally declares.

“The boys were after me. A lot of boys were after me,” she recalls with a grin. The braver ones would call out to her during la passeggiata, telling her she could do a lot better than Tarzan. Or warning her that she was dating a thug, that he would beat her black-and-blue.

It seems clear to me that the relationship was changing Tarzan more than Shamis. Once they begin dating, there are no more mentions of fights or tantrums.

Shamis was studying to be a teacher; Tarzan began attending the university and working on his geology degree. Shamis still wasn’t a true member of the Beizani—for that she should have been born in Mogadishu and attended a private Italian school. But her sophisticated ways were rubbing off on Tarzan. And he had another reason to feel more settled, too. The allowance he’d been receiving from Somalita for playing on their basketball team had given him the means to reach out to his mother, still living as a nomad, and bring her and her two youngest sons to live in Mogadishu.

“Two hundred and fifty shillings!” Tarzan remembers. He kept a hundred, rented a new room in town for twenty-five shillings, and ate at a cheap restaurant for fifty shillings a month. The rest of the money was enough to rent a house for his mother and a growing crowd of relatives. Before long, he was looking after the six children of a jailed half-brother, too.

The half-brother’s story is a curious one. He was a policeman who’d been part of a firing squad called to execute a woman convicted of murder. The woman had killed another in a jealous rage. Three times in a row, every policeman on the squad deliberately aimed to miss, and all were sentenced to a year in jail. When his half-brother came out of jail, Tarzan used one of his orphanage contacts, now working as an exam supervisor, to help him cheat his way to a job at the national printing press.

Tarzan was now twenty-three, and with Yusuf training in Russia, he was shouldering a growing number of responsibilities. Money was tight, and his prospects seemed limited.

Perhaps he would have found a job, and stuck it out. Perhaps he could have won over Shamis’s family, who were opposed to their relationship, and settled down in Mogadishu. But Somalia was changing tack once again, and the Cold War was about to intervene.