“The country is going down into the drainage.”

—MOHAMED NUR ADDE

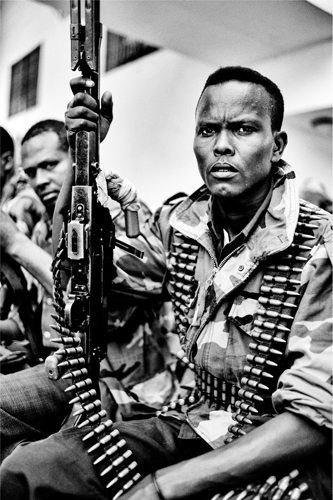

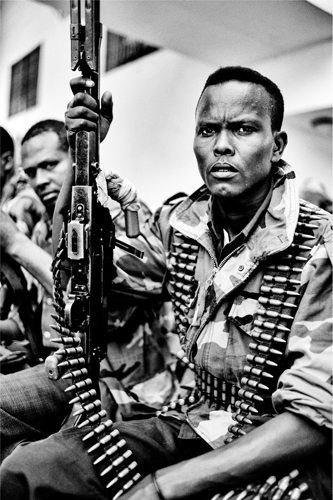

Gunman, Mogadishu, 2011. COURTESY OF PHILIP DAVIES

WHEN DID IT BECOME INEVITABLE? Was there a moment when Somalia stopped merely losing its way and began accelerating toward the cliff’s edge? It’s easy enough to wind back the clock and find traces of a nation’s path toward disintegration. But when you’re in the thick of it, how do you decide it is time to give up on your own country?

Somalia’s exodus began as an unobtrusive trickle. It’s tempting to wonder whether a nomadic culture helped to disguise the early signs of the disaster to come—whether the old habits of traveling light and following the rains somehow masked, and only later encouraged, the great uprooting, the spasms of migration that shuddered through an imploding country.

Or maybe the truth is simpler—that only the wealthy and the intrepid run before the alarm bells become deafening, before there is no other choice left.

In a way, you could argue that Tarzan and Shamis were among the first to abandon Mogadishu. A year after he left, he secured all the necessary permits for her to join him in Saudi Arabia, and they settled down to what sounds like a rather dull life. They rented an apartment in the city of Taif, on a high and relatively cool plateau east of Mecca. Tarzan’s Arabic was distinctly ropey, and his English was rough, but he managed to bluff his way into an interpreter’s job at the outpatient wing of a local military hospital, and then switched to the physiotherapy department, working as a recreation officer and arranging wheelchair sports for injured soldiers. Sports and organizing. The job seemed to suit him. Soon the first of six children was born. Ahmed was quickly followed by Mohamed, then Muna, Ayan, Mimi, and Abdullahi. Three boys and three girls in the space of nine years.

“Yes, she was very fertile. And I was very fertile,” Tarzan chuckles.

But if the impulse to leave Somalia had been, at least in part, political, the decision to stay abroad was entirely about money. For the first time in his life, Tarzan was earning a good salary. He was becoming the self-made man he’d always imagined being. He built two houses for his relatives back in Mogadishu. While he was still working at the hospital, he became the Saudi agent for a British company that built hand-control car units for disabled drivers.

Shamis, on the other hand, found Saudi Arabia’s conservative traditions restrictive and boring. It was a grim contrast with her carefree life in Mogadishu. “I like to be free, not stuck inside!” She began wearing a headscarf—out of necessity, although later, in London and Mogadishu, it would become the norm. She was unable to leave the apartment without her husband, and she had few friends. “You don’t mix. You say ‘hi’ to the neighbors and that is all.”

Still, they were making a family, she’d finally patched things up with her aunt, and on balance life was good.

But in Mogadishu, President Siad Barre’s dictatorship was becoming more intolerant and unstable. For those who cared to listen, the sounds of impending trouble were obvious.

Poets and activists were being locked up. Nuruddin Farah was already in exile. His first novels—scathing about some aspects of Somali society—had riled the president, and while Nuruddin was traveling abroad he learned that he would be arrested and perhaps sentenced to death on his return to Somalia.

Shamis’s friend Samiya left early in 1982. Her stepfather, disillusioned by the wasteful, foolish, unsuccessful Ogaden war, told her a bigger storm was coming. “He told me, ‘Get out of here. Save yourself, the country is going down into the drainage.’” Samiya had already fallen for a British aid worker and soon followed him back to London.

Gabyow, Tarzan’s friend from the orphanage basketball team, joined the civil service in Mogadishu, then left to study accountancy. In 1980 he got a scholarship to continue his studies in Britain, and when he returned to Somalia two years later he discovered the place had changed. It was as if people were slowly giving up.

“When I go back, I find people don’t want to be accounted! Ha! They all want creative accountants! They say, ‘Take your car, take your wages, go back to your house,’ and let us continue to steal.” He went back to Britain for good, returning to Somalia only once, for the briefest of visits.

So what was going wrong?

* * *

LATE MOST AFTERNOONS, AN earnest young man called Ali Jimale Ahmed used to walk across the well-swept courtyard at Villa Somalia toward a large tree that spread its cool shade like a giant carpet outside the president’s office. For an hour or two, he would sit in the shade surrounded by a group of perhaps nine men from the president’s personal security detail and would teach them a “smattering” of English—enough, he’d been instructed, for them to get by when they accompanied Siad Barre abroad.

Ali Jimale had studied at the nearby 15th May Secondary School with Tarzan and Yusuf. He and Yusuf had been friends since childhood—two bright, academic, serious boys. He used to tease the devout Yusuf about his wild older brother, saying that he’d have to account for Tarzan’s sins, one day. But Ali could see how the orphanage had shaped Tarzan—he was “feisty, I don’t think he had anyone to turn to for help. He had to fend for himself. His physical prowess helped. You couldn’t sort of mess with him, but as I remember he was not a bully. He was not. He was always interested in politics.”

Ali was part of a small group of scholars preparing an official biography of President Barre. They worked at a government office across town, but as the leader of the group, Ali would often come over to Villa Somalia to talk to the president.

Siad Barre was an austere, often gloomy, complex man, who had only recently moved his offices from the military barracks near the orphanage to the hilltop Villa Somalia. The giraffes that had roamed the compound in the years after independence were long gone. Barre proceeded to throw out most of the more lavish furniture that had survived, preferring to sit under the tree, where Ali would sometimes join him, scribbling furiously to catch his words.

“You see the difference between the Argentinians and the Somalis?”

It was the summer of 1982, and Britain’s naval task force had just regained control over the Falkland Islands after a ten-week war. Argentina’s President Galtieri—like Siad Barre, a general who’d come to power at the head of a military junta—had been forced to resign following mass street protests.

“Somalis are noble, honorable,” said President Barre, thinking about his own treatment after the disaster of the Ogaden war. “When we were defeated, they did not ask for my head.”

Ali sat quietly, his pen paused on his notepad, thinking—but not saying—that no Somali would, or could, dare to demand Barre’s resignation. This was not Argentina.

In fact, there had been an attempted coup in Mogadishu after the Ogaden fiasco, and if you’re looking to pluck out the threads of history that lead toward Somalia’s unraveling, the failed 1978 uprising by a group of army officers is worth holding on to as an early sign of trouble. Specifically, of clan trouble.

Successive Somali governments had tried, since independence, to shake off the influence of clans, to deny them any public role or space. It was a modernizing project for a new nation, a form of social engineering that no one, surely, could argue against. In the 1960s civil servants were told they could no longer mention their clans when introducing themselves. They were all Somalis now. Nothing less.

Rwanda’s authoritarian government tried something similar in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide, insisting that there was no such thing as “Hutus” and “Tutsis”; that experiment has yet to run its course.

In Somalia, plenty of people embraced their new, post-clan identity. But others started referring to their “ex-clans” and using other euphemisms that made a game out of the whole process, and inadvertently strengthened the sense of clan as something secretive, something forced underground, a truth that would not die.

Siad Barre took the anti-clan purges even further, burning effigies and insisting that Scientific Socialism had no place for old hierarchies. But what seemed at first like a revolutionizing instinct soon changed into something more destructive. What the president came to mean was that there should be no rival system that could threaten his own grip on power.

Sitting under the tree in Villa Somalia late one afternoon, as the sun dipped toward the inland horizon, Ali could not help but notice the uncomfortable reality in front of him. The president’s guards sat in their green uniforms, some clutching their red berets and repeating a few basic English phrases. All nine men were, Ali knew beyond doubt, members of Siad Barre’s sub-clan, the Marehan. Many were even close relatives, nephews and so on.

It was the clearest proof that, for all the president’s public speeches against clannism, only blood counted when it came to his security. Besides, as opposition to his dictatorship grew, it became increasingly convenient to dismiss his critics as mere clannists. Which is what happened with the military coup plotters of 1978. Tarzan’s brother Yusuf—still in the army—knew some of them well and was convinced their motives were patriotic, but the president chose to frame it differently.

Over the next few years, Ali was summoned to Villa Somalia more often, and not just for the presidential biography or to teach English. Siad Barre’s intelligence services had been checking up on him and found that he knew how to keep his mouth shut.

“I have nothing on you,” the president told Ali one evening in a manner that seemed to suggest both flattery and threat. He had started calling his young visitor “compagno,” the Italian word for “companion,” and would often let off steam, furiously denouncing his ministers for an hour or more.

“Thank you. You can go now,” he would tell Ali at the end of an evening. It was kind of crazy, Ali remembers. “I was kind of his therapist.”

* * *

THE CLAN DIVISIONS WOULD not heal. As opposition parties began to form and face persecution, they would retreat into the corners of the country and, by default if not design, into their clans’ safety nets. And as President Barre lashed out more aggressively, so the clans became more relevant and more powerful.

Still, Somalia’s collapse did not yet feel inevitable, or at least not imminent. Tarzan’s old university was churning out graduates. Foreigners were still pleasantly surprised to find the streets far gentler and safer than Nairobi’s. There was even a grass-less golf course. There weren’t many tourists around—visas had always been a problem—but Princess Ann managed a visit; and Somali Airlines served goat stew, rice, banana, and a “quite decent claret,” according to Jeremy Varcoe, British ambassador at the time. Some weekends the ambassador would drive south along the coast beyond Merca, past the newly nationalized banana plantations, to a villa shared by several Western embassies.

“The Italian ambassador—very charming—was still the most powerful diplomat. One Christmas we ate spaghetti and drank a very fine champagne. My wife had given me a pair of Union Jack swimming trunks, rather mischievously, and I wore them on the beach. The other ambassadors were deeply shocked that I would wear a national flag in such a way—that it was disrespectful.”

In Mogadishu, the clubs and restaurants were still thriving along Lido beach. But a slaughterhouse had opened north of the city, and the current brought goat blood and other waste straight past the city’s beaches. Shark attacks became almost commonplace, even in the shallows just offshore. The German ambassador’s daughter lost an arm. Soon, almost no one swam at Lido anymore.

Mogadishu’s Italian community was still more or less intact. Lino, the boy scout who witnessed the 1969 coup, had since gone into business with his brother. They would drive around Somalia overseeing engineering projects, particularly the construction of new roads—mostly paid for by foreign aid.

In 1986 Siad Barre was badly injured in a car crash and became even more aggressive and suspicious toward his critics. Summary executions became commonplace. The army leadership was packed with members of the president’s clan.

Then, in 1988, Siad Barre lashed out with a brutality that seemed to hurl Somalia toward the cliff, ordering warplanes to bomb the northern opposition stronghold of Hargeisa. The city was almost completely destroyed, and some half a million people fled across the border into Ethiopia. After that, it became hard to imagine a way back from civil war.

Lino stopped driving far outside Mogadishu and hired an armed guard to travel in his car. And then, on a Sunday in July 1989, he heard that the Italian bishop of Mogadishu had just been shot dead by an unknown gunman inside the city’s cathedral.

Bishop Salvatore Colombo had lived in Somalia for more than forty years. His death prompted a frenzy of finger-pointing that seemed to highlight all the forces now pulling the country apart. Was he killed by Islamists who claimed he’d been trying to convert Somalis to Catholicism? Was the president simply getting rid of another vocal critic? Had the bishop somehow made an enemy of the wrong clan? Or was the opposition trying to stir up more trouble?

Lino didn’t know and didn’t care.

“He was my teacher, my religious guide. From that moment I understood there was no chance for Somalia,” he says, and as he pauses to consider that, he remembers another moment, a few months later, after his wife and children had moved to Kenya. He was at dinner with a wealthy Somali businessman and found himself sitting next to one of the president’s nephews, an army colonel.

“We are a royal family,” said the colonel. He meant his Marehan clan. “We’re like the royals in Saudi Arabia. And if we lose this fight, all of Somalia will be destroyed.”

The Italian embassy tried to reassure those of its citizens who hadn’t already made plans to leave. There was “no emergency.”

* * *

THROUGHOUT THE 1980S, ALI Madobe had risen fast through the ranks of Somalia’s intelligence services. It would be easy to believe that was entirely on merit. He’s an imposing character with a sharp mind. But as he himself admits, the fact that he belongs to the same “sub-sub-clan” as the president can only have helped his career.

Since the split with the Soviet Union over the Ogaden war, Madobe had been to the United States, Italy, Britain, and Egypt for training. He became a full colonel and eventually the head of Somali counterintelligence. From within the system, he could see more clearly than most the extent to which the president’s Supreme Revolutionary Council was losing power.

At the end of 1989 he tendered his resignation to President Barre, who rejected it with the same indignation that he showed toward the many attempts to mediate an end to Somalia’s deepening political crisis. Six months later, Madobe finally persuaded the president to let him travel to the United States to complete a master’s degree. The Americans refused to let him bring his family, so Madobe, increasingly convinced that trouble was coming, sent them to Dubai. But toward the end of 1990, without Madobe’s knowledge, his uncle persuaded his wife and three children to return to Mogadishu.

When he found out, Madobe rushed back from Colorado, arriving home in mid-November 1990. Just in time.

Fifteen days later, he says, “the civil war erupted.”

Madobe could see the situation was desperate. He was still an officer in the intelligence services and was immediately summoned to the National Intelligence headquarters in the center of the city. Opposition groups and clan militias now controlled much of the country and had come up with a mocking new title for the president. He was, they insisted, nothing more than the “mayor of Mogadishu.”

Since the murder of the Catholic bishop, the number of killings had risen sharply and, in a chilling glimpse of what was to come, the city was starting to reorganize itself along clan and sub-clan lines, like a pack of cards being un-shuffled, as families moved into relatives’ homes in areas they considered safer. In a land where grudges had always held a special value, they were accumulating with dangerous speed. Red berets began appearing on the streets beside the bodies of the dead—an attempt by the government’s enemies, Madobe was convinced, to make it seem like the president’s personal guards were to blame.

He still felt an intense, complicated loyalty to Siad Barre. Not, perhaps, purely because of the clan system—Madobe still considered himself an orphanage boy at heart—but because he respected the president’s character and achievements.

I can hear the admiration in his voice as he talks about him now. His modest, austere lifestyle. Even his ruthlessness.

“I believe he was a kind and good man. He put his personal interests behind those of the country and people. A lot of people say, ‘Oh, that dictator created a lot of problems, blah, blah, blah…’ But he changed this town. He built it. He was very wrong to concentrate all the development in Mogadishu, and leave out the rest of the country. But if I consider the whole history of the world, starting from Napoleon, Mussolini, Hitler … these people create history. So Siad Barre created the history of Somalia, or a part of Somalia.”

Was he really a Napoleon? Hardly. His ambitions were local and, ultimately, selfish. He destroyed his country by obstinately refusing to negotiate. Perhaps Syria’s President Assad would be a better comparison.

Over the next few days Madobe watched the police, the military, and even his own intelligence services begin to disintegrate along clan lines. Moving around town became difficult, especially at night. He decided to stay at home. His house was in Medina, on the southern edge of the city, just up the slope behind the airport and near the American embassy and two big hospitals. It was becoming a stronghold of the Darod tree, from which the Marehan branched. Injured relatives began arriving at his house.

On Sunday, December 3, the sound of gunfire clattered across the city. Opposition forces—mostly drawn from the Hawiye tree, including some who had gathered, with Ethiopian backing, near Tarzan’s family pastureland—had begun to fight their way into Mogadishu. The city’s cosmopolitan days were coming to an end.

Madobe called his uncle Loyan, who was still living on the far side of the city. He’d been in charge of Somalia’s immigration service, but more recently—and presumably for reasons of clan—he’d also become a member of the intelligence services. Madobe begged him to come across to Medina. It would be safer. Loyan insisted that the two men, now the senior figures in their family, should remain apart.

“It should be only me. Or only you,” Loyan said, meaning that if one of them were to be killed, the other could take responsibility for the family.

On the night of January 25, 1991, President Siad Barre’s family was taken in an armed convoy up to Villa Somalia. The show was nearly over. Twenty-four hours later the president and his entourage would drive out of Mogadishu, never to return. But for now, the first family needed a loyal escort, and Loyan volunteered to accompany them through the streets of Mogadishu.

An armored car led the convoy. Loyan came next in his Nissan, followed by the president’s family. Halfway along the still-elegant, tree-lined Somalia Avenue, near the Juba Hotel and the main post office, the Nissan stalled. Loyan jumped out, abandoning his car, and leapt onto the running board of the vehicle behind. The convoy raced off again, but with a gun in one hand, Loyan struggled to keep his footing. By now the convoy had nearly reached the foot of the hill below Villa Somalia.

Madobe has struggled to piece together exactly what happened next, but it seems ambushers were hiding in trees on either side of the road and opened fire on the convoy. One bullet hit the driver of the vehicle carrying the president’s family and a swaying Loyan. For a few seconds the driver lost control and, as the car swerved violently, Loyan was hurled onto the road.

The convoy raced on, up the hill toward Villa Somalia. Loyan’s body was found the next day. The country was now in free fall.