“Whatever you can do to save your family, you do it.”

—SHAMIS ELMI

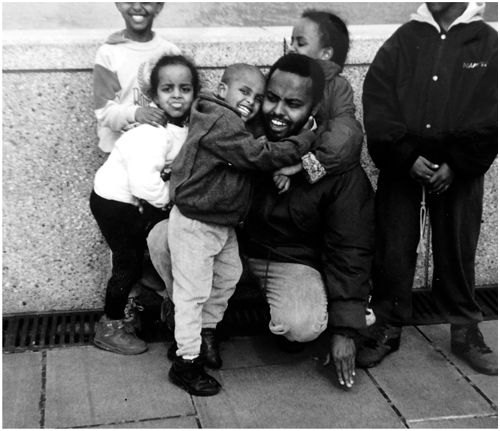

Tarzan with children, London, 1993. COURTESY OF SHAMIS NUR

THE DOUR WHITE MAN AT the immigration desk was not convinced.

“I can tell you understand me. I think you speak better English than you’re letting on,” he said.

Shamis stood at the counter in front of him, feeling far less intimidated than she’d expected. Her youngest child, eleven-month-old Abdullahi, was in a stroller beside her. The other five children stood to one side, watched over, in a halfhearted sort of way, by Shamis’s seventeen-year-old half-sister Sahra.

“I don’t speak English,” Shamis repeated to the man, in English. What she really meant is that she couldn’t understand his accent or his questions. “I’m a refugee,” she said, and again listed the names of everyone in the group.

It was an unusually cold Thursday afternoon at London’s Heathrow airport. December 4, 1990. Margaret Thatcher had stepped down as prime minister a fortnight earlier. Britain’s economy was sinking into another recession, and a thick blanket of snow was about to cover the country.

When Shamis remembers that day, she veers between two extremes.

Sometimes she talks about “the hardest” time of her life, the exhaustion, the stress, and the desperation to save her family from the horrors unfolding in Somalia. At other times it feels like she’s describing an adventure—hectic, unpredictable, but hardly worth complaining about. And it’s that second impulse that strikes me as a better clue to Shamis’s real character, and perhaps to her relationship with Tarzan. They are matter-of-fact people, and neither of them seems inclined toward regret.

Tarzan had waved the family off a few hours earlier at the international departures hall in Sofia, Bulgaria.

“Goodbye. I love you,” Shamis remembers him saying. “You know, the normal thing that a husband says to his wife and kids.”

They’d flown to Sofia from Damascus. At the time, Somalis could travel to Syria without visas. In the crowded markets of Damascus’s old town, Tarzan was put in touch with “people who can arrange to get others into Europe.” People smugglers. But he decided the risks were too great, and besides, he’d learned of another option. “Stickers—forged visas. They were easy to get hold of.”

“Sweden or England?” The word from other Somalis was that those countries were the best bets for asylum. The choice came down to the language, and Tarzan chose English. The fake visas weren’t supposed to fool immigration officials in the U.K. But he was assured they’d be good enough to get the family on the plane in Damascus, through an overnight transit stop in Sofia, and then a couple of hours in Brussels.

It’s striking how quickly and resolutely Tarzan seems to have made the decision. There were other options available. London was a gamble, and one that would affect them all for decades to come. But I can imagine him snapping his fingers, as he often does when he’s explaining things.

And again I can’t help reaching back to Somalia’s nomadic culture for an explanation. Home is where you need to be, not where you were born.

A year earlier, he’d decided the family had no future in Saudi Arabia. The work was still good, but they were treated as foreigners there and always would be. Arranging schooling was becoming a struggle, and Shamis was increasingly frustrated. Besides, the country had always been a temporary home in Tarzan’s mind. The map above his bed in the orphanage was of America, not the Middle East.

So in 1988, Tarzan uprooted the family and moved them back to Mogadishu. He had plans to use his Saudi contacts to help set up an import business, bringing construction materials across to Somalia. Shamis was already doing some wholesale business of her own, shipping clothes back from the Gulf. They both knew that the political situation was unsteady and worrying, but it wasn’t until the plane touched down at the familiar beachside airport, and they drove up and over the hill to their new house, that they realized quite how far things had deteriorated.

All their friends were talking about the curfew, about the nighttime killings of prominent people. Suddenly, war seemed almost inevitable. Shamis was worried her aunt might be a target. For the first time in her life she felt the weight of her Hawiye ancestry and her own prominent lineage pressing down on her, marking her out in the wrong sort of way.

Tarzan seems reluctant to talk about their brief return to Mogadishu.

“There’s nothing I can tell,” he says, curtly. Later he adds, in the voice of someone tired of explaining the depressingly obvious, “It’s always the clans. It always splits along clan lines. And that way, the conflict always spreads.”

And so they left Mogadishu, returned to Saudi Arabia, and began making plans to fly to Damascus. Shamis asked her father if she could take her half-sister with her to help with the young children, and he agreed.

At the immigration desk at Heathrow, the man asked for their passports. Shamis shrugged and shook her head. Someone in Damascus had told her it was better to arrive with no documents, and so she’d gotten rid of them on the last flight from Brussels. To compound the growing sense of dislocation, their luggage had disappeared en route, never to be found.

For a week, the entire family shuttled back and forth between Heathrow and what seemed like a very luxurious airport hotel. Shamis was embarrassed to discover that British Airways was footing the bill as a form of punishment for allowing them on the plane in the first place. After that, they were moved to a place called the Thorncliffe Hotel, with other asylum seekers, in a nearby suburb called Hayes. The children watched a new television series called Mr. Bean.

By 1990, plenty of families had already arrived in London from Somaliland—the northern region that government airplanes had bombed so viciously two years earlier. Now, with Somalia collapsing into anarchy, the numbers were rising fast.

Before long, bloated corpses littered Mogadishu’s streets, a frenzy of looting erupted, and tens of thousands of civilians—above all, the Darod, who bore the brunt of the invading militias’ fury—began to flee. It became known as “clan cleansing,” as legitimate opposition to President Siad Barre curdled into a battle for supremacy between the Hawiye and Darod. Some of the displaced fled on foot, and some clambered onto trucks, heading first inland to the market town of Afgoye and then on to their clan strongholds and beyond to neighboring Kenya and Ethiopia.

* * *

IN LONDON, SHAMIS CAME to feel she was being punished, or at least marked out, for being a member of the Hawiye, whose militias were leading the attacks in Mogadishu.

“People who came after me, or before me, got refugee status. But not us. At that time my clan is the one who was fighting with the government. But I don’t care. My clan, they are not me. Whatever you can do to save your family—you do it.”

It seemed odd to me, at first, that Tarzan did not accompany Shamis to the U.K.—that he would let his young family struggle through the lengthy asylum process in an unfamiliar country without him. Money was one obvious factor. He could return to Saudi Arabia and keep working, for a year or two, while his family tested the waters in the U.K. Then there was Shamis herself—a resourceful, confident woman who could certainly cope with any challenges ahead.

But it’s my sense that Tarzan was wrestling with other issues. The years in Saudi Arabia faded into the background. He was now profoundly reluctant to let go of Somalia, to acknowledge that his country had gone past the point of no return, and, perhaps most of all as a proudly self-made man, to submit to what he felt was the indignity of becoming a refugee.

After a couple of months at the Thorncliffe, the family was moved to a council house near Victoria Park, in Hackney, east London, while their asylum application was processed. The older children were enrolled into two local schools, and Shamis—who had grown up with cooks and housekeepers and taxi rides to school—found herself plunging into an unfamiliar, exhausting routine. She’d rise at six, drop the four older children off at their schools, take the younger two with her to a local college where she took English language classes, come home at noon to clean the house and cook, head out to collect the kids from school at 3:30, feed them all, supervise homework, bath time, bedtime for all six children, then ironing, and finally bed for herself.

Her half-sister Sahra was not much help. She was a teenager and quickly found her own life in London, going to college and returning home after the children were asleep.

“How can I be depressed? I don’t have the time,” Shamis told herself, clinging on to some of that old Mogadishu panache.

She wondered what British people made of her—a dark, skinny, attractive, young-looking woman in Western clothes, her frizzy hair sometimes uncovered, walking through Hackney with Abdullahi in the pushchair, Mimi balancing on the back of it, and Ahmed, Mohamed, Muna, and Ayan all following behind.

“Are those really all your kids?” people would ask, usually more curious than hostile. Even admiring. She looked too young to have so many.

A few weeks after they’d settled into their house in Hackney, Shamis managed to track down the telephone number of an old friend. Samiya had finally settled in London, marrying a “humble” man who worked on the London Underground.

When Samiya rang the bell, she assumed a weary, worn-down woman would open the door. That’s how she felt, and she had only three young children to handle.

“Look at you! You’ve lost weight, you’re even slimmer, and prettier,” said Samiya admiringly, as they embraced. “I was expecting a lady with no teeth!” She was referring to Tarzan, still half-convinced the Mogadishu street fighter would prove to be the sort to beat his wife.

“No! I beat him!” Shamis answered with a grin. She explained that Tarzan was still in Saudi Arabia, that he’d gone back to Mogadishu after leaving the family in Sofia, but it was just impossible in Somalia. And now look what was happening to the place. They both shook their heads despairingly and exchanged news about other Mogadishu families who were still trying to flee.

“Fauzia Nur lost seven children. She came by ship from Mogadishu. All the people died. Only she survived.”

The news seemed unremittingly grim. And their friends were, by and large, the ones with money, not the masses herded into camps or forced to walk through the wilderness. They’d heard recently of a ship packed with refugees that had been barred from docking at a port in Yemen. The word was that 150 people had died of thirst.

Ali Madobe was safe. He’d finally managed to drive out of Mogadishu with his family, heading to the southern port of Kismayo. But the journey was treacherous, and there was fighting in Somalia’s second city, too. They headed inland and eventually managed to cross into Kenya and then, with some sleight of hand, to Dubai. Madobe’s brother already had permanent residence there and pretended that Madobe’s heavily pregnant wife and children were his own. You do what you need to do. From there, through other Somali friends, they made their way to Tehran, Czechoslovakia, and finally to Holland.

Abukar Dahir, the young banker who would later be caught up in the 2014 attack on Villa Somalia’s mosque, was only two years old at the time. His mother, Sadia, a deputy assistant minister of health in the old government, was on a work trip to India—a surreal indication of business-as-usual even in the midst of impending civil war—when her family decided to escape from Mogadishu. They drove south, like Madobe, to Kismayo, and Sadia rushed back, just as the first Gulf War was beginning. She chartered a plane from Nairobi to try to rescue them, but there was too much gunfire at Kismayo’s airstrip for the plane to land. Instead the family drove on to the Kenyan border where huge crowds were gathering, desperate to escape the violence. There were stories of starvation and of lions attacking the stragglers.

Eventually, refugee camps were established across the border on a rocky, thorn-infested plain inside Kenya. Over the years the Dadaab camps—a chaotic assortment of homemade huts, donated tents, markets, schools, and white prefabricated cabins—grew until they’d become a seemingly permanent home to nearly four hundred thousand people. In all, perhaps one in seven Somalis, well over a million people, would flee abroad.

But those with money and contacts did not linger in Dadaab. Sadia had brought cash, in case she needed to bribe the Kenyan border guards, and a diplomatic passport. She managed to get most of her relatives to Nairobi, and then the family moved on to Damascus, Moscow, Sweden, and finally to London.

* * *

FOR THREE YEARS, SHAMIS and her children waited for a decision from the British immigration authorities. Finally, in 1993, a letter arrived by post at their home in Hackney. One year’s “leave to remain” on humanitarian grounds. Hardly generous. But as grudging as the letter seemed to Shamis, in truth this was the bureaucratic equivalent of a confetti parade. The doors began to open.

One week later, the family was informed it could move from the “temporary” house in Hackney to a roomy top-floor council flat just off the busy market street of Queen’s Crescent, in north London, with a glorious view over the city. It would be their home for the next two decades. One week after that, with the help of a lawyer and advice from Ahmed’s schoolteacher, Shamis finally secured a visa for Tarzan. He’d been in Saudi Arabia, working and waiting. Now, with the help of a Saudi friend at the Italian embassy, he got a visa to travel to Rome, where Shamis sent his official invitation by courier.

Seven-year-old Ayan was woken by the doorbell ringing late one night in 1993. She wandered out onto the landing from her bedroom and immediately rushed back to check the photograph she kept under her pillow. Shamis had decided not to tell the children anything in case it didn’t work out. But it was definitely him.

Tarzan had flown into Gatwick airport, south of London, earlier that evening. It was his second time in Britain. He’d come in 1986 for a short trip to meet the company that was exporting hand-operated car controls to his hospital in Saudi Arabia. By then his old basketball friend, Gabyow, was already living in London, and he remembers Tarzan indignantly rejecting the idea of becoming a refugee, saying, “Never in my life. It’s an insult.”

This time Shamis had told him to take a train to London and then the tube to Kentish Town Underground station. It was ten o’clock by the time he walked out onto a dark high street and waved down a taxi for the short ride to Gilden Crescent.

Tarzan does not find it easy to admit to weakness. Or to being wrong, for that matter. But from the various descriptions he’s given me of the next few months, it’s clear that he sank into a profound gloom; refugee blues. The first morning he woke late. The children had already left for school. He stood on the balcony, staring at the gray, distant panorama of London, from the spiky towers of the City, past St. Paul’s Cathedral, the Post Office Tower, and all the way west over Primrose Hill toward Heathrow. “So,” he thought, “this is what they call London.” Then he slunk back inside and didn’t leave the house for five days.

Shamis was trying to find work. She’d been attending a teacher training college and soon she’d begin volunteering at the local primary school, helping immigrant children—particularly Somalis—to fit in. But for now, money was tighter than ever, and Tarzan was proving stubborn.

For a long time, he just walked the streets, all the way down into central London and back, along Camden High Street, turning right on Malden Road, up the hill, three flights of stairs, and into the flat. This was not the life he wanted. It was not his to control anymore. He felt emasculated.

One day, an exasperated Shamis finally convinced him to walk with her across to Fortess Road to catch the 134 bus north, up to Archway and a sixteen-story tower that housed the local social security offices.

They took a numbered slip from the machine and sat waiting for Tarzan’s turn to sign up for welfare payments. He looked about him. Alcoholic people, he thought. Old people. Rough people. He started shaking his head and turned to Shamis.

“We cannot stay here. Let’s go back.”

“We need this. I need this. Sometimes we don’t have food,” Shamis replied.

“I cannot queue with these people. Even if I’m dying. No way.”

They left the building, and Shamis gave her husband a few days to calm down. But it was hard. They were really struggling to pay the bills. If Tarzan applied for welfare they could get another £25 a month. Eventually, they came up with a compromise. Tarzan went back alone to Archway Tower and applied, but when the checks started arriving in the post, he signed the backs of them, and Shamis took them to the post office to cash in.

* * *

A FEW WEEKS LATER, Tarzan was on one of his regular walks down Camden High Street when he saw a small advice center on the left-hand side of the road, and a decision he’d been wrestling with for some time finally snapped into place.

He was thirty-seven years old. There were plenty of odd jobs around. Cash in hand. Enough to get by on, and who knows, maybe it would lead to something better. Or he could stay on the dole and, as he saw it, end up like the wretches in the queue at Archway Tower. Or he could admit that an unfinished university degree from Mogadishu and all his work experience in Saudi Arabia were worth precious little in Britain, and that he needed to swallow another mouthful of pride and resume his education.

He was told he needed to complete a one-year access course before he’d be eligible for higher education, and he chose business studies at a college in Tower Hamlets, east London. There were plenty of closer, easier options, but he worried that he’d end up finding excuses not to go and would drift toward casual work. It was better if he had to leave early each morning and take the train. It would almost feel like having a proper job.

Each year, the local council gave out a handful of discretionary grants for students who wanted to study at a university. One evening, after a day at college in Tower Hamlets, Tarzan filled in the application form and took it to one of his teachers to polish up his English. He wanted, he wrote, to be “a role model” for the growing Somali community in London.

It sounded like the old Tarzan was back—pushy, ambitious, always the first with his hand in the air.

Twice, when I ask Tarzan what he did to relax in London in those early days, he mentions the television. I assume he means the news. After all, Somalia was constantly in the headlines. But Tarzan was concentrating on something else—O. J. Simpson’s murder trial in California.

“I was obsessed,” he admits. “I woke up every night at 2 a.m., even when I was studying. At the time I thought he was innocent—that it was about racism. But now I think he must have been guilty.”

It’s easy to see why a Somali might choose to forget about events in Mogadishu at that time. The news was unimaginably, shamefully, unspeakably grim.

Any hope that rival opposition groups might reach a power-sharing deal to replace Siad Barre’s dictatorship with something—anything—resembling a government quickly vanished. And in the absence of legitimate authority, the vacuum was filled by the only structure still functioning in Somalia, the one system that now seemed bound to make matters even worse. The clan.

This was the time when Mogadishu first became internationally synonymous, justifiably, with anarchy and despair. All the news clichés were true. It was now a bullet-riddled patchwork of clans, sub-clans, and sub-sub-clans whose loyalties and feuds seemed to change by the day and made sense to almost nobody.

It was no better in the countryside. In 1992 clashes between rival warlords triggered a famine in southern and central parts of Somalia. Before long, the United Nations was sending peacekeepers to Mogadishu in order to get humanitarian supplies to those who needed them most, and away from the militia groups and ragged entrepreneurs who could, and would, only see foreign aid as a source of power and profit.

And then at the end of that year, with the world’s media already on the beach to film it all, American troops landed at night in Mogadishu, squinting into the camera lights, at the start of a mission to reinforce the UN and “save” Somalia.

I was not in the country to see the iconic calamities that followed—the sight of American Black Hawk helicopters being brought down by nimble clansmen with rocket-propelled grenades, the bodies of American soldiers being dragged through the streets by indignant crowds, the U.S. military’s humiliating withdrawal from Somalia, and the UN’s startling decision to abandon the country, too.

It was only in 2001 that I made my first trip to Mogadishu. But it was like visiting a crime scene, years later, and finding the evidence undisturbed. The rusting hulk of a U.S. helicopter still lying where it crashed. The archeology of Somalia’s implosion eerily intact.

I thought I knew something of war. I’d spent all of the 1990s living in the former Soviet Union and had covered many of the conflicts prompted by its collapse, including Russia’s two astonishingly brutal campaigns in the breakaway republic of Chechnya. The ferocity of the fighting there and the sheer firepower available were staggering. Helicopter gunships, fields of artillery, vast tank columns, and fighter jets. Villages, towns, and indeed the entire city of Grozny were flattened like Stalingrad. But that was war at full speed: short, intense battles with astonishingly heavy casualties and specific goals.

Mogadishu was something entirely different.

* * *

EIGHT SCRAWNY YOUNG MEN in flip-flops, T-shirts, and combat trousers were waiting for me at a rutted dirt airstrip 50 kilometers outside the city. A hot wind tore across a flat, hazy landscape. This was where the daily khat flights rushed in from Kenya, with their consignments of precious fresh green leaves for the fighters to chew each afternoon. We’d flown in from Nairobi, a few hours after the morning khat scramble, on a tiny charter plane. There were no formalities, no immigration control, just a crowd of cars and armed men.

It’s jarring to think that twenty-seven years earlier, Shamis and Samiya had driven past the same spot as their truck took them from a bustling, ambitious city into the countryside to begin teaching Somalia’s new alphabet.

Our guards, each clutching a battered AK-47, were responsible for security at a hotel in town, just off the K4 roundabout. The hotel manager, a relaxed young Somali called Ajoos, had driven out in a second pickup with heavily tinted windows. We squeezed into the rear seat, and three members of the security team clambered onto the back, while the rest followed behind in what I can only describe as a sawn-off truck—its roof, windows, anything higher than the steering wheel, all sliced back to the bone.

Between the airstrip and the city, we passed through perhaps half a dozen makeshift roadblocks. Sometimes just a piece of rope dragged across the road, sometimes a metal pole or chunks of concrete. And always more of the same wiry, wary gunmen in flip-flops, peering at our tinted windows.

It was, Ajoos explained, partly a question of math. Eight guards would probably be enough to guarantee a shit storm all around if anyone decided to make trouble. So we’d mostly likely be left alone. But it was also about clans. The checkpoints belonged to a variety of different groups. Murusade, Habr Gedir, Abgal. And Ajoos had carefully selected his guards, as if from a pack of cards, from a range of sub-clans—partly so they wouldn’t conspire together and sell us off to the highest bidder and partly so that someone would, hopefully, be able to spot someone they recognized at each checkpoint; maybe even a relative who could wave us through.

On the outskirts of Mogadishu, sweating heavily into my flak jacket now, I saw the first civilians, and it seemed to me that they scuttled, backs to the wall, between doorways. Then again, adrenaline can give even the most ordinary scene a veneer of danger.

Approaching the K4 roundabout, our driver leaned on the horn and pushed the car forward through a herd of goats. Speed clearly meant safety, and as our pickup slowed almost to a halt, the guards in the car behind leapt off and fanned out on the road around us, guns raised, scowling faces hunting for trouble.

The city looked as though it had been bleached. From the dirt road to the buildings, the ruins, the people, and even the air, everything seemed to be variations of the same sand-gray color. Then, as we accelerated toward the hotel’s huge metal gates, an impossible burst of scarlet leapt out like an ambush. A giant bougainvillea plant. The city’s trees had almost all vanished, chopped down for firewood, but somehow the bougainvillea—planted in more hopeful times—had clung on around the city, providing the occasional, delirious splash of pink, red, purple, or orange blossoms.

An hour later, we left the high walls of the Shamo hotel. Our guards were driving ahead of us now—gun barrels jutting out of the car like a giant porcupine—as we headed down Medina Road, toward the seafront, and past the tip of the airport runway, unused now except toward sunset when a few hundred boys would emerge from the tents and ruins nearby to play football on it.

As the road flattened out near the dunes, it swung to the left, past the old army headquarters where President Siad Barre had once slept during the first years of his dictatorship. If I had known to look at the building opposite, I’d have seen the walls of Tarzan’s old orphanage as we swung into Via Londra. Soon afterward we passed the abandoned British embassy, and then, on the right-hand side, the San Martino Hospital where Tarzan claimed to have been born. We were now speeding along the same road he had sprinted down when he thought Yusuf had drowned.

A few hundred yards later, with a bright flash of light, the sea leapt into view on our right, and our little convoy came to a sudden halt.

The scene around us was mesmerizing.

Waves crashed on the dark rocks. Offshore, like a shark’s mouth, the tip of a shipwreck seemed to leap from the ocean, gleaming in the afternoon sun. Behind us, a distant rattle of automatic gunfire skipped across the ruins.

It felt like a war zone, for sure. I caught a glimpse of a “technical”—one of the improvised fighting vehicles and warlord status symbols, with a giant machine gun mounted on a tripod—rolling quietly down a side street. But there was something else, something I’d never encountered in Chechnya, something strangely still and unnerving.

I could see it in the seams of ancient garbage that coated the dirt roads and even the rocks along the shoreline, like geological formations, cracking to reveal layers of compressed, grimy sediment. I could see it in the bullet holes that didn’t just crowd around a few windows to target a sniper but seemed to decorate every inch of every surface that still stood upright. And I could see it in the ruins, always so fresh and livid in Chechnya, but here transformed, as if by some mad architect, into dusty warrens, festooned with plastic sheeting and scraps of corrugated iron, and repopulated by families—a thousand wary eyes peering out at us—who’d gambled on the hope that an apocalyptic city could be safer than the countryside. And I could see it in what was missing—in the apparent absence of anything of value—every window frame, every street lamp, every wire, every tree, every hint of modernity stripped down, hacked apart, and carted off.

Battlefields are the most terrible places. But the horrors are usually temporary. Mogadishu had mutated into something far more disorientating and rare—a permanent battlefield, staffed by a cast of brutalized thousands who had come to see war not as a temporary aberration to be endured but as a way of life.

There were, for sure, some parts of the city that seemed less damaged, where shops and even universities were operating, and where the electricity poles groaned under the weight of a thousand cables that spoke to the ingenuity and entrepreneurship of Somalis who could thrive in any situation. But not this neighborhood.

We got out of Ajoos’s car and I walked toward the old lighthouse at the corner, where the road turns sharply inland toward the city center. A cannibalized gray minibus crawled past us with nothing covering its engine, a set of cow horns tied to the front, and the windshield of a far smaller car ingeniously welded in place in front of the driver.

“Stop!” It was the first time I’d heard Ajoos sounding nervous, and I swung around sharply. A barrier lay across the road just in front of me.

I hadn’t noticed the barrier because it was invisible. A metaphorical line in the sand. But Ajoos, and everyone else in the city, could see it. It was as clear as the afternoon rain shower now drifting in from the ocean, or the holes punched into the walls of the lighthouse, or the giant gray ruins of the old Al-Uruba hotel beyond.

We had reached the border of one clan’s territory and the start of another’s.

* * *

BACK IN LONDON, IN 1995, Tarzan slammed the telephone down in a fury.

In addition to resuming his education—he was now studying business at the University of Westminster—he’d begun trying to get funding for a small community organization he’d set up for Somali kids in the neighborhood around Queen’s Crescent.

The local authorities were ready to help, but only if Tarzan’s group could merge with three other tiny Somali organizations that also wanted funding. A local church had already offered him space, but he’d rejected that with something close to alarm.

“At the time we were afraid of everything! To go inside a church? We thought you’d change your religion straightaway if you did that!”

So Tarzan had rung up one of the other Somali groups, and an old man had immediately asked him, “Which clan are you?”

“I’m Somali,” Tarzan replied indignantly.

“There is no Somali here. I’m Marehan. Are you Hawiye?”

“You destroyed our country, and still you are proud to call yourself that? Still, even here, you are dividing people by clan?” Tarzan was shouting now.

It was inevitable, of course, that some of the battles, the grievances, and the rivalries festering in Somalia would survive the journey to London and elsewhere. How could they not? Throughout the 1990s thousands of Somalis were arriving in Britain each year, and, at the very least, it was logical that they would try to move into neighborhoods where they knew they’d find relatives.

The phenomenon is almost certainly exaggerated, but for some, a map of London, even today, is divided into clan territories. The Isaq in the east of the city—Mile End, White Chapel, Stamford Hill, Greenwich, Woolwich, Stratford. Head north to Kentish Town, King’s Cross, and that’s the Majerteyn. And so on. The theory extends beyond the capital, to cities like Birmingham where the Darod are considered strong. And it has deeper roots in history, from the first Somali seamen who came to ports like Cardiff and Liverpool in the late nineteenth century.

Something similar was happening in America, where more than a hundred thousand Somalis would be granted refugee status and were soon building substantial communities in cities like Minneapolis, St. Paul, Seattle, and San Diego.

* * *

THE 105 BUS ZIGZAGS through the edge of west London, from just beyond Wembley stadium all the way to Heathrow airport. Late one evening a group of young Somali men watched Adam Mattan climb up to the top deck and walk past them.

“Oi! You. You’re not from this postcode.”

“Certainly I’m not. I’m just taking the bus. I’m leaving your postcode,” Adam half-stammered. He was a tall, thoughtful student with an unruly and—for a Somali—unusually long mop of black hair.

“OK, cool. Not a problem. Which clan you belong to then?”

Adam’s mind was racing. He could recognize some clans from their accents, but he couldn’t be entirely sure. All he knew was that they seemed well educated, and probably went to college like him. He was scared. If he said the wrong clan, or sub-clan, he was reasonably sure he’d get beaten up or perhaps even stabbed.

“I don’t know my clan.”

“You bastard! You’re talking crap.”

“Sure. If that makes me a bastard, then that’s fine. But I don’t know my clan.”

Adam grins, his long arms flapping, as he acts out the incident, years later. We’re sitting in the office of the organization he now runs, just behind the railway line and the covered market in Shepherds Bush, west London. The organization is called the Anti-Tribalism Movement.

“So what clan are you from?” I ask, a little provocatively. Adam giggles politely and declines to answer. No, he really won’t tell me. There’s a principle at stake, one that is shored up almost every day, whenever his telephone rings and a member of his clan asks for money to settle some dispute or other back in Somaliland.

“It happens to me every day. EVERY SINGLE DAY. They say, ‘Our sub-clan and XYZ clan are fighting over grassland near our village.’

“And I say, ‘Is there any way it can be resolved without firing a bullet?’

“And they say, ‘What?! How can you ask that? How can we split it?’

“So I say, ‘I will not be a murderer with my money,’ because if I send a hundred quid, that money pays for an AK-47 and someone is killed. ‘Screw all of you!’”

Adam is a natural actor, and I can feel his indignation growing, his hands waving in fury. He talks of a recent clan battle over land that he says led to about three hundred deaths in the northern region of Somaliland—the vehicles, the food for the fighters, the petrol, the ammunition, all paid for by families living in the U.K. And some of them were on benefits here, Adam says with contempt.

“Do anything you want with your own freakin’ money. But not the money we all work for and that has been given to you to feed your child!”

And then, of course, the dead overseas must be avenged or paid for with “blood money.” We’re back to the logic and habits of nomadic life—where, in the absence of any other judicial system, the clan elders would settle disputes. But now the blood money is being gathered in foreign sitting rooms and transferred around the globe by remittance companies. And the value of one life depends on many factors—the status and power of his sub-clan, the size of his family, and the nature of his career.

“Our blood is more expensive than theirs,” Adam says in a light, supercilious tone. He’s acting again, explaining how four men from a small, “marginalized” clan might be killed to avenge the death of one man from a bigger clan, and how blood debts can be put on hold, banked, sometimes for years, until an appropriately respected figure comes of age to be murdered.

“I remember like daylight—like it was yesterday—someone famous from my clan was killed by another clan.” But rather than targeting the murderer, Adam’s clan waited for more than fifteen years and then killed “one of the best of the best” from the other clan in a town in Somaliland.

“I couldn’t believe what was going on here in London. Boys my age were celebrating,” says Adam, slowly shaking his head.

* * *

THE CLANS COULDN’T BE ignored. But it turned out that with a little patience and maneuvering, they could be brought together. Up the hill in Queen’s Crescent, Tarzan was making progress as a community activist, and in Camden, rival groups finally united to build the Somali Youth Development Resource Centre.

Some people bristled—as they still do—at Tarzan’s style. He was a forceful, blunt character, maybe a little intimidating at times. And he was a charismatic public speaker. “He wanted it all for himself. He had puppets everywhere,” one colleague grumbled to me recently.

But Tarzan was not the type to be held back by criticism. He began working for the local council as a refugee employment and education advisor and soon set up his own organization—the Somali Speakers Association—offering support and guidance to new arrivals across the borough of Islington.

“A lot of people were carrying all that trauma from the war. It was just really hard coming here. Too many Somali men were just sitting around chewing khat,” says Sarah Lee, who hired and worked with Tarzan as he tried not just to find jobs for Somalis but to convince them it was a good idea to work in the first place.

“He was a good guy. Funny. You could tell he was a leader, and the community loved him.”

“How could you know that?” I ask.

“Mainly because so many people came to see him. He had masses and masses of clients. And he could convince them.”

At home, Tarzan’s children were turning, effortlessly, into Londoners, with strong local accents and only a hazy idea of the country they’d left behind. It was strange to hear their father talking so earnestly about Somalia, about the orphanage, and basketball, and how he would like to be buried there one day. From their British perspective, they imagined it as somewhere backward and grim, and asked ignorant questions, and laughed when their parents talked nostalgically about going out to the cinema together in Mogadishu.

“We’d be cracking up!” says Abdullahi.

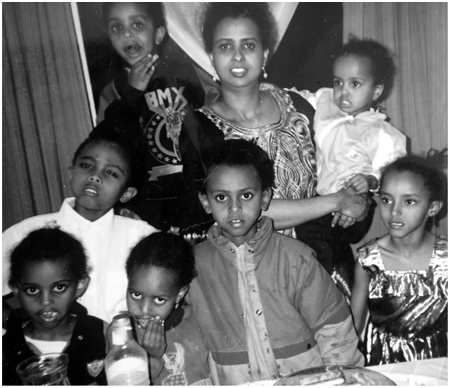

Shamis with the kids, 1991. COURTESY OF THE NUR FAMILY

For years, Abdullahi was a difficult, hyperactive child. At home, after school, he would crouch behind the television set mixing flour and oil together on the floor, then pelting his older brothers and sisters.

“I swear, if I had this child I would either kill him, or kill myself,” said the lady next door. Tarzan sometimes felt almost the same way—“Believe me, he was crazy.” Shamis was more patient, but still, she admits, “Abdullahi was DIFFICULT! I could not sit when he was awake.”

The oldest boy, Ahmed, had the occasional run-in with the police. “He could be a little bit rude,” Shamis concedes. But Mohamed was quiet and earnest, and all three girls were thriving academically.

All six children went to the state primary school in a stern Victorian building just down the street. Shamis had become a support teacher there, helping other Somali children who had arrived more recently to master English. She organized coffee mornings for the new parents, explained the local bus routes and the welfare system, and still struggled with the rent on their council flat. London was growing on her, and she was good at making friends. Even the local drug gangs—Somali or otherwise—would leave her in peace now that they started to recognize her from school.

Years later, I’m sitting outside a café in north London with Abdullahi and his big sister Ayan. He’s now a gangly, charming, scatterbrained, information technology graduate looking for a job. She’s taking a lunch break from the private clinic nearby where all three of Tarzan’s daughters—all university graduates—now work. Ayan has her father’s almond eyes, a neat black hijab covering her hair, and a quick, warm laugh.

“I’ve always been a daddy’s girl!”

“He spoiled you,” Abdullahi teases, and then adds, “Mum used to spoil me.”

They talk about the camping trips that Tarzan would organize through the Somali Speakers Association for families that couldn’t afford holidays. A different place outside London every summer. As a teenager, Ayan used to help out. Abdullah, too, but he says he didn’t have any Somali friends when he was growing up. Only in sixth form.

“Somalis always used to call me ‘white boy’ cos I only had, like, white friends!” he says, and with that, perhaps inevitably, the conversation veers toward the subject of clans.

Both insist they grew up neither knowing nor caring about their own famously small clan. Abdullahi says he found out about the Udeejeen when he was a teenager but didn’t know where the branch fit in relation to the bigger clan tree. And it wasn’t until Ayan was about seventeen that some Somali girls started “acting weird and raising eyebrows,” and then one friend said, “Why don’t you ask Ayan—she’s from that tribe.”

“And I remember going home that night and asking my dad, ‘Am I this tribe?’

“And I remember my dad laughing, and saying, ‘Don’t buy into this filth.’”

By now, Tarzan seemed settled in London. Not as much as his children or Shamis, perhaps. But he was certainly busy. He still preferred to walk everywhere, and I can picture him weaving briskly through the regular Thursday market in Queen’s Crescent, a well-known figure heading off to a management meeting or to check up on the internet café he’d set up on the nearby Seven Sisters road. The lumpy scar on his forehead came from a fight at the café with some Albanian “thugs” who, Tarzan insists, came off worse from the encounter.

Before long, his ambition started nudging him toward politics. He joined the Labour Party—“I believe in social justice, and I don’t like the Conservatives’ policy toward immigrants and non-British”—and he applied to run for a seat on the local council. Things might have worked out very differently if he’d won. But he signed up late and was selected to contest an unwinnable seat. The consensus among Labour activists at the time was that his heart wasn’t really in it anyway; his real focus had begun to drift elsewhere.

They were right.

Back in Somalia, the years of pure anarchy were ending. A window of political opportunity was opening, and Tarzan could not resist. He felt the tug of home, of patriotism, and perhaps, the nomadic impulse to keep chasing the rains. But the changes in Somalia were uncertain, and with them came the acute danger that chaos might be replaced by something even more menacing.