“A change will come.”

—MOHAMUD “TARZAN” NUR

Lido beach, Mogadishu, 2015. COURTESY OF BECKY LIPSCOMBE

IT’S FOUR IN THE AFTERNOON, and the streetlights along Queen’s Crescent are already starting to flicker into life, nudging portions of the gloom aside.

“Let’s cook!” Tarzan shouts down the hall to Abdullahi, who recently lost his job and has spent the day in the flat, lounging on his bed with his headphones on.

“I’ll cook for the children, Abdullahi. When are they coming?”

Tarzan stands by the kitchen stove in a checked shirt, sarong, and bare feet, emptying a tin of tomatoes into a frying pan. Shamis is away this week, at their apartment in Dubai.

“I’m learning,” he says cheerfully. “My wife spoils me. Treats me like a king.”

It will be spaghetti again tonight. Soon the tomatoes are sizzling, and the sounds of shouts and giggles float up the stairs from the front door.

“Awowe! Awowe!” Before they’ve even reached the kitchen, Malia and Maya, now seven and ten, are calling out the Somali word for “grandfather.”

“I love you.” Tarzan greets them with a simple statement of fact, then a hug, and tells them to go and say their prayers while he finishes cooking.

“More tea?” he says to me. I’m sitting behind him at the kitchen table with my back to the window and the darkening silhouette of London’s skyline, waiting for the right moment to begin.

It’s been five years since I first met Tarzan in a crowded room in Mogadishu’s Villa Somalia, and perhaps three years since I first began to consider writing a book about his life. It’s a strange relationship to have with someone. He agreed to the book idea immediately and apparently casually. Plenty of foreign journalists were interviewing him in those days, popping into Mogadishu to talk to the man with the “most dangerous job in the world.” It was all good exposure for an ambitious politician.

But a book is a much longer project, and it requires a degree of trust and cooperation I was not entirely sure how to sustain. Besides, there was the constant and very real possibility that, on any given day in Mogadishu, he would be killed. We’d shared a near miss, once, when he’d been called out to settle a dispute at an army checkpoint on the edge of the city and a roadside bomb had detonated, killing eight soldiers a minute or so after we’d both left the area.

I had warned Tarzan that I would not be airbrushing out any dirt I found out about him.

Still, as he leaves the sauce bubbling on the gas stove and turns to join me at the kitchen table, I’m wondering how he’ll react now, whether things will get awkward.

I tell him that I’ve got a series of questions—about alleged corruption, about his life story, about a lie that he’s told me. I’ve asked him about some allegations before, but I’m also aware that I’ve been saving this moment, biding my time, waiting until I’ve got as much material as I think I need for the book, worried this could be the end of our relationship.

Tarzan leans back in his chair and says, “Fine! Fine.”

He sounds pleased and impatient, like a restaurant guest being told the oysters are on their way. And I realize, almost immediately, that I already know how this is going to go, that he is not the sort of man to be cornered, or intimidated, by mere questions.

He scoffs at Fartaag’s insinuations.

“I have nothing to hide. Nothing to hide. Whatever he says is suspicious. Fartaag was with the prime minister. I’m the only politician in Somalia who can stand in front of the public and say, ‘Ask me any question you want. I don’t care how rude, how confrontational. You’ll get an answer.’”

And he proceeds to talk about the municipality’s accounts. How the government’s auditor general checked and approved them every year. How his rivals—corrupt rivals—tried to undermine him with rumors. How no one can actually point to a specific incident. How, by the end of his term, he’d set up a computerized accounting system that rendered fraud impossible. How he’d left a tidy sum in the municipality’s accounts for his successor. And besides, he said, coming back to Fartaag’s question about getting foreign auditors in:

“How could we afford to pay for PWC or Ernst and Young? Do they work for free?”

I ask him about the land deals. The claims that he was taking kickbacks and money abroad in suitcases. What about the apartment in Dubai?

Tarzan sits forward now. There’s finally a hint of indignation in his voice as he begins listing his property and business interests: a share in the old internet café here in London, a share of another business in Birmingham, the Mogadishu villa he built for his mother from the money he was earning in Saudi Arabia, and another one that he finished in 1986 but never lived in. Then there’s a big chunk of land—150 by 350 meters—on a main road leading out of Mogadishu that he ended up selling for half a million dollars. In 2004 he bought an apartment in Cairo. “Property was cheap at that time, and there was no hope for Somalia.” He mentions another “cheap” piece of land in Mogadishu, bought more recently, but he doesn’t want to say where it is in case the government “misappropriates” it. The apartment in Dubai is rented, and Shamis is “really struggling” with the shop she’s opened there.

It all comes out in a torrent, and when he’s done, he sits back in his chair.

“I was a businessman before I got into politics. This is the apartment I’ve lived in since 1993. That’s the couch I bought before I became mayor. This is the kitchen that the council just renovated. I still pay rent here. So when people accuse me of corruption, I won’t waste my breath defending myself.”

And yet it’s obvious that Tarzan can’t quite leave it at that.

His children—fiercely protective of their father—have been getting grief on social media. Mimi, the youngest daughter, was accused of getting Tarzan to buy her a new car with stolen money. Abdullahi posted holiday snaps from Dubai on Instagram and got asked if his dad was buying more villas.

“I used to get really angry. But now it’s just funny. I know my dad better than anyone. He knows what will happen on judgment day. Know what I’m saying?” Abdullahi asks.

But how do you disprove the allegations and the rumors in a place like Somalia? And perhaps more significantly, how does it affect people to live in a society where the very concept of uncontested truth seems to have been utterly eroded? It was like his brothers warned him when they told him not to take the job. You’ll smell of the sewer. Tarzan compares it to an Ebola outbreak. A city like Mogadishu is so contaminated that any politician quickly becomes tainted and suspect. In the end, you can never convince everyone. That’s the price of admission. It’s also rather convenient.

The girls come in to fetch their spaghetti and take the bowls, carefully, into the sitting room to eat in front of the television. Abdullahi wanders in again, headphones still on, and tells Tarzan about getting made redundant from his part-time hospital job.

“You’re smart,” Tarzan replies. “Volunteer. Don’t ask for money first. Volunteer.”

When Adbullahi drifts back to his room, I turn the conversation, warily, to the story of Tarzan’s birth. I’m more apprehensive about this than I am about the corruption allegations. I know for certain that he’s lied to me about being born in room 18 at the San Martino hospital.

Tarzan looks up. Then he grins. He offers two explanations. And I suggest a third.

The first one begins with his accent. For some reason he’s never quite shaken off the rural lilt that marks out those who’ve grown up in the wilderness of the Ogaden. So when he became mayor of Mogadishu, people—particularly from other clans—started whispering that he wasn’t really a local, and that he didn’t “belong” in the city. Tarzan took it as a challenge and an insult. It was like being called “bastard” all those years ago at the orphanage. And so he constructed an elaborate story.

“The Martino hospital was by the ocean. So I said, ‘Anyone who is born closer to the ocean is more Mogadishu than me. But anyone born further inland than me is not from Mogadishu!’ I even invented room 18. So with that argument, I silenced the argument. No one can challenge me.”

“So you’re saying, ‘It could be true, in theory’?”

“Yes, it could be true! Believe me! The facts themselves have no value.”

No value. It was the cornered orphan, lashing out. Undaunted, threatening, and effective.

The second explanation is really just an extension of the first. Like so many Somalis of his generation, Tarzan has no idea exactly when or where he was born. So why not invent your own story?

Perhaps it’s not really a lie at all. Just a different way of looking at identity—as a suit one chooses rather than something imposed. While Tarzan is trying to articulate that thought, he talks about his own offspring.

“I don’t know how to put this exactly, but my children, they have the right to say they’re Londoners.”

I think I understand him. It feels like the dilemma of the modern nomad. What happens to your roots when you move? And I immediately think of Shamis, ruefully describing herself as a second-class citizen in two countries and wondering why anyone should be trapped by the accident of birth.

“But what about your mother?” I ask Tarzan. I’ve been thinking that maybe the story about her coming to Mogadishu to give birth was, at least in part, his way of feeling closer to her.

Tarzan brushes that theory aside. “She had no role in it.”

The remaining tomatoes, for our dinner, are starting to burn, and Tarzan gets up to stir in some more water from the kettle. His mind is still back at the orphanage.

“I’m not ashamed of my difficulties there. I used to borrow clothes. Nothing was mine. Did I tell you that I had insects in the bed? So you scratch yourself. One night I couldn’t sleep so I went outside to where they’d been digging a well, and I buried myself in the sand. I slept there. This is a part of my life. I’m proud of it. It’s not my father who made me. It’s me.

“I’m the Tarzan.”

He’s heading back to Mogadishu first thing the next day, stopping off en route in Abu Dhabi for a conference, then Dubai for a few days to see Shamis. We say our goodbyes, and I head off down the hill toward Camden. It’s morbid, but I can never help wondering whether I’ll see him again or whether his luck will run out before our next meeting. I know he ponders much the same every time he takes leave of his children in London. I find myself checking his Facebook profile several times a day. He’s become very active online, and I get the sense he’s worried about falling off the public radar now that he’s no longer mayor. He’s set up a new political party, the Social Justice Party, as part of his campaign to become president, and he’s always jumping at every hint of a media interview, or a plane ticket to visit diaspora groups in Sweden, or Holland, or anywhere else. But he’s a political outsider once again, worried about funding, scratching at the door.

* * *

THE NEXT MORNING IS cool and windy. It drizzles for a few hours, but by lunchtime London is looking freshly scrubbed and self-assured, as I stand outside Moorgate Underground station, in the financial district, waiting for Abukar Dahir to arrive.

He’s an hour late—stuck in the Swedish embassy trying to renew a passport—but we quickly fall into our usual rhythm, striding fast through the city, south toward the Thames, across Southwark Bridge, and then down onto the crowded embankment, heading west.

Abukar has always seemed more pensive in London than in Mogadishu. And today he has more than usual on his mind. He’s just decided he doesn’t want to go back to Somalia anymore. He’s done with it. And the realization has dislodged something—nudged the boulder away from the cave entrance.

“I try to make myself busy. But it creeps up, in a funny way. It’s not guilt, but when I’m having a very good day, it comes back to haunt me,” he says, hunting for the words to describe the weight in his chest.

It feels like familiar territory. I’ve covered many wars in the twenty-five years I’ve been working as a foreign correspondent and have seen and learned something of the damage such experiences can inflict. I ask him if he feels like he’s abandoned his post. He pauses and looks toward the river. We’ve just passed the Globe Theatre, and we’re walking through a block of shade cast by the Tate Modern art gallery’s high tower.

“That’s the question. It’s difficult to answer. And do I really even want to get an answer?”

He starts talking about his first trip back to Mogadishu. Too scared, at first, to get off the plane but fueled by a sense of mission—almost like he was seeking redemption.

“If I knew what I know now, would I still have done it?” he asks himself, probingly. He hasn’t decided yet.

Abukar has been having troubled dreams, often when he’s heard of another friend being killed. There was a guy from the Somali diaspora living in Poland, a builder, who left his family and went back recently. His business was just starting to pick up in Mogadishu when it happened. And there was a girl. Abukar has mentioned her to me before but skated over some of the details.

“It was during a rough period between me and my fiancée. I got to know this girl, Sahra, and she was very nice. On Friday morning we were supposed to go to Lido beach. But the night before, she was taking her little brother to hospital, walking past the K4 roundabout.

“We heard the explosion. And I thought nothing more about it. But later, I called her, and phoned, and phoned. And the next morning we drove round to pick her up from her home, to go to the beach, but she wasn’t there. We all went to the beach anyway.

“So it turns out there was this Qatar delegation coming from Villa Somalia, and Al Shabab was targeting the convoy. She was standing right next to the cars. She was blown to bits, with her little brother. Splattered on the wall.” Abukar is almost whispering now, and I have to lean in as we walk, to catch what he’s saying.

“That was … It was like somebody just ripped me apart. That somebody can be killed, just like that. And you know, it means you don’t want to get attached to people. You’re just so scared all the time to lose someone.”

We’ve just passed the National Theatre and we cross the river again, heading toward Whitehall and into the parks around Buckingham Palace.

For years, Abukar told anyone who would listen that Mogadishu was on the mend. Like Shamis, he felt stronger knowing he was making a difference, that it was worthwhile. It’s not that he’s lost all hope now. “But at the same time I realized I was losing everything that was important in my life.” He means his fiancée. His family back in London. He never told his mother what he was going through. Seeing the severed heads of suicide bombers. What it felt like to have someone else’s blood on you.

Instead he began to develop his own rules about how to stay alive. Never go to Lido beach on a Friday. Never go out between noon and 2 p.m. when all the security guards take their lunch break. Avoid restaurants. Never get cocky about safety. And if you’re flying out of Mogadishu, go to the airport first thing in the morning and just wait there.

Finally, he decided to leave for good.

And now it all feels surreal, almost like it never happened. It’s made him wonder about his Somali-ness, and about how much it’s linked to geography. He feels more British than anything else now, and he’s even thinking about giving up his Somali citizenship altogether.

“It’s still hard, speaking about this. All these fears build up. They have such a profound effect on you, but I don’t even understand it yet.”

But he knows one thing for sure now. “I came back in the nick of time.”

* * *

FOR ONCE, MOGADISHU IS buried in rain clouds. On our first attempt at landing, the plane overshoots the runway, swings sharply to the right over a slate-gray sea, and roars back up into the whiteness. A few minutes later we’re safely down and taxiing across a flooded apron toward the newly completed airport terminal—a sharp-edged, expensive-looking, giant shoebox of a building and a powerful statement of confidence. Another milestone for Somalia.

As we all queue up quietly in the air-conditioned arrival hall, I think back to all those angry, sweaty scrums—for bags, for immigration, for bribes—that used to mark the start and end of any trip to Mogadishu. How quickly we adapt to our surroundings.

But outside, it’s back to the usual routine. Five armed guards waiting in our escort car. Rain-drenched Ugandan troops manning the barricades. Tight chicanes formed by white concrete slabs to slow down any suicide bombers. And then we’re out onto the tarmacked airport road, heading into the city.

“These’ll take forty-seven rounds before they start to crack,” the British private security guard in the passenger seat says, tapping the window. It seems ludicrously precise.

I can’t get hold of Tarzan at first. So instead, I head up to see Ahmed Jama at his Village Sports restaurant. The rain has stopped now, and the traffic is moving smoothly around the K4 roundabout. As we head up a side road, I scan the walls for new adverts. They’re something of a Mogadishu specialty—bright, detailed, hand-painted pictures covering every inch of the outside walls of shops, depicting exactly what they’re selling inside, from cereal and toilet paper to car parts and computers. I was once told they were a sign of failure—a response to the fact that generations of Somalis can no longer read. But they strike me now as a celebration of commerce and a happy tradition. They also can be surprisingly graphic. The pictures outside some private clinics show childbirth and other available “procedures” in eye-watering detail.

Advertising, Mogadishu, 2015. COURTESY OF BECKY LIPSCOMBE

I find Ahmed in his outdoor kitchen, wielding a frying pan, and talking to two young members of staff. I can smell wood smoke and something spicy. There’s swordfish steak on the menu today, and samosas, spaghetti, omelets, camel stew, and fresh doughnuts.

As usual, Ahmed is full of plans. He’s building a new restaurant inside the military camp at the airport, and another in Hobyo, an ancient port city up the coast where his grandparents came from, a place more famous these days for its pirates.

“I’ll be opening that one next year, if I’m still alive. Ha.”

The sentiment is familiar. But the tone has changed. Ahmed sounds weary, like someone going through the motions. He looks it, too. Big bags under his eyes. He’s survived six attacks now, some by Al Shabab, and others, he’s sure, from business rivals.

“We never give up,” he says. But then he lets out a sigh. “There’s always hope. Always hope. But we can’t keep running. It looks like this government is a bad one. The problem is still corruption.”

I ask him if he’s still in touch with Tarzan, and something flickers across his face.

“I don’t see Tarzan. I don’t go with him. He made some good money, so…”

“What are you hinting at?” I ask, surprised.

“I’m hinting because … we know what he’s done. If you want the truth, ask him.”

“But you were friends, right?” I had no idea they’d fallen out.

“We were friends. We came here to change something, but if you ask people about Tarzan, they’ll tell you who he really was.”

That’s all he wants to say on the subject. But then he asks me why I’m writing a book about Tarzan. And I think I know what he’s getting at. In recent years a number of Somalis have asked me the same question. Although it’s not really a question at all. It’s a rebuke. It’s like Fartaag said in his email—why can’t you write about “the true heroes of Somalia”?

I give my usual, neutral, and, I hope, honest answer—that it was chance, convenience, and curiosity that led me to Tarzan. That I wasn’t looking for a hero, per se, but rather someone willing to share an interesting life story that seemed to follow Somalia’s own turbulent path, or at least to intersect with it from time to time in startling ways.

Ahmed offers a curt laugh. “Well, good luck to him.”

We say our goodbyes, and I get back into the car, thinking about the indignation that I’ve provoked from other Somalis. It’s not just that some people don’t like Tarzan. It’s not just about clans either. It’s something more abstract and profound. Somalia doesn’t get much outside attention, and when it does, it always seems to be of the wrong sort.

I’ve come to picture it like this. It’s as if Somalia has been buried for a generation, with foreigners like me standing on its grave carving the words “failed” or “pirate” or “terrorist state” on the headstone, and ignoring all the grieving, exiled relatives standing to one side, trying to point out that Somalia isn’t actually dead, that it’s finally coming back to life, and that the next words to be written—on a celebration banner, not a tombstone—should, at last, be their own words, or at the very least, should be words that they can all agree on, all be proud of.

But what would those words be, I wonder. And after all this time, is agreement even feasible?

* * *

TARZAN IS SITTING BAREFOOT and alone on his porch, sipping tea with a dash of Somali honey, and fidgeting with his two mobile phones.

He seems unusually subdued, and it soon becomes clear why. He’s feeling trapped. It’s like he’s under house arrest. When he was mayor, the government and his clan were responsible for providing security. But now he’s on his own. He has to pay for everything. And even his cousin Fanah has found a new job running one of the city’s bigger police stations.

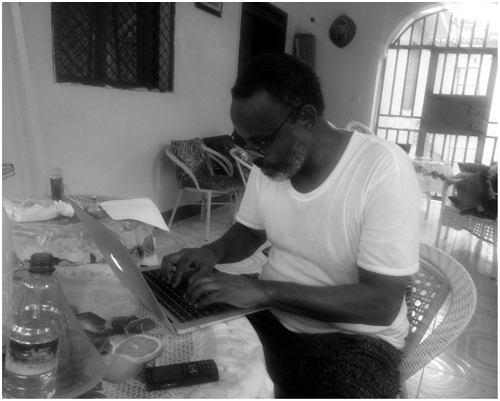

Tarzan at home in Mogadishu, 2015. COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

Tarzan hardly ever goes out now. And frustration has quickly turned to resentment.

“If I was a simple citizen I could enjoy my freedom. But I compromised my security to come and work as mayor. And I did a good job—everyone knows I did a good job. Now the government is supposed to protect me and pay my income. But they don’t protect me,” he says bitterly.

And that leads into an angry outburst about the president. It’s odd. Within the space of a minute, Tarzan can be the cautious diplomat, declining to criticize individuals by name. Seconds later, he’s singling out senior officials and accusing them of corruption—of openly selling off public land to the highest bidder.

“A change will come,” he warns darkly. He means when he becomes president.

But the political process isn’t working in his favor right now. And I wonder if it ever will. Tarzan is convinced he has a chance to win a one man, one vote presidential election in Somalia. He’s always believed that. But not for the first time, those in power seem to be finding reasons to keep the electoral process limited to the votes of a few carefully chosen clan and regional representatives.

We sit in silence for a moment, sipping our tea, and I listen out for gunshots. I realize that I haven’t heard a single one since I arrived. It’s hardly scientific, but it sounds like progress.

It seems like the right moment to ask Tarzan about what happened with Ahmed Jama—about why they fell out.

“He’s a very strange character. A very bad character. Impulsive. Lonely. He cannot cope,” Tarzan declares abruptly.

Then he goes off on a tangent, and it’s almost like he’s declaring his creed. As familiar as I’ve become with his clear-cut worldview, his certainties, and his confidence, I’m caught off guard.

“Anyone against me is a bad person,” he says.

“Anyone? Really?”

“Let me repeat. Whoever is on my side is in the right. Whoever is against me is wrong. People hate me for the wrong reasons—they’re people who are highly corrupted, and those with a strong clan mentality. But people love me for the right reasons.”

I can hear, in that voice, the angry orphan challenging any boy who dares to mock him, and the hard-skinned adult carving a path through a forest of enemies. But it is a little unnerving, too.

* * *

IT’S PAST FOUR IN the afternoon when Tarzan and I set off for a drive around town. He seems keen to get out of the house, and between us we now have ten armed guards to watch our backs.

We turn out of the cul-de-sac, down the hill toward the barrier beside the national theater, and swing to the left. Tarzan is in tour-guide mode. There’s the spot where Shamis’s old school used to sit—the place he first met her. That used to be the Chinese embassy. This was Casa Italia, the old Italian club. Then the Shabelle Hotel. A nightclub. The banana export agency. The Juba Hotel.

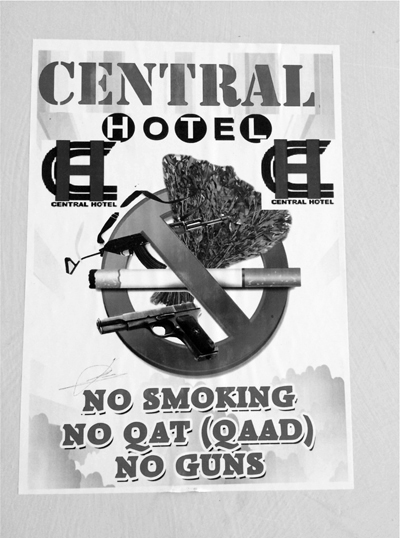

We pass near the Central Hotel, too, and I think of an email I recently received from its owner manager. Ahmed Hussein came back from Sheffield, England, two years ago, inspired, at least in part, by Tarzan. But the hotel has recently endured two major suicide attacks, and now Ahmed has decided to cut his losses.

Central Hotel, Mogadishu, 2015. COURTESY OF BECKY LIPSCOMBE

In his email, he said the only customers he could get to fill his hotel were government officials. But that leads to two problems—attacks from Al Shabab and the fact that “the government does not pay. I therefore concluded that there are no business opportunities unless you are connected with corrupt officials, or equally corrupted Al Shabab.”

We turn a corner, and Tarzan peers through the armored glass.

“There used to be an Italian butcher somewhere here,” he says, pointing at another spectacular pile of rubble. Even now, for all the new building work going on, you’re seldom far from the ruins in Mogadishu.

Tarzan starts telling me a story. One I’d never heard before—about a close relative who had joined Al Shabab.

Hussein was Tarzan’s cousin, his father’s brother’s son. He’d been living for many years in America and was tall, handsome, and devout. But Hussein had surprised his family, first by becoming a fashion model, and then by abruptly leaving the United States for Mogadishu, where he briefly visited his mother before disappearing. He had, it seemed, gone to join Al Shabab.

Tarzan says he received a warning phone call at some point in 2012. CIA officials in Mogadishu had apparently tipped off Somalia’s security services, believing that Hussein might be planning to use his family connections to get close to the mayor.

“If you see him, if he comes close to my house, shoot him,” Tarzan promptly told his security guards.

But Al Shabab was suspicious of Hussein. The group assumed he was working for the CIA and treated him accordingly. After several months, he decided to escape, and with the help of another disillusioned diaspora recruit, he hid in a lorry packed with bananas and made it back to his relatives in Mogadishu. Five days later, an American drone killed Al Shabab’s leader, Ahmed Godane—reinforcing the suspicion that Hussein was, indeed, a spy and a traitor.

“So now he’s hiding in Mogadishu. He’s wanted, dead or alive, by Al Shabab,” says Tarzan. The whole story is making him chuckle. “He’s a weak man, a chicken, so scared. He has no life right now. NO LIFE!”

Tarzan went to see him recently.

“I told him, ‘You’re the most foolish person I’ve ever met.’”

“Did you ask him if he planned to kill you?”

“Yes. He said, ‘No, never.’ But I cannot trust him.”

Our convoy stops outside the old basketball stadium—the scene of all those teenaged dramas and of the exhibition match with Oscar Robertson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. There’s a big sign over the gate now that reads “Wiish Stadium.” The place has been renamed in honor of Wiish, the referee who sent Oscar Robertson off for dribbling the ball “incorrectly.”

A dozen girls are training on the outdoor court. There are new floodlights and a couple of advertisements painted on the stands. The next-door building, three stories high and riddled with bullet and shell holes, looms over one end.

Tarzan spots an old friend, someone who was once on the national team, and begins reminiscing. The man, who has been coaching the girls’ team, sees me and promptly declares, “We need Tarzan to become president of Somalia! Truly, he was good as mayor. We saw improvements.”

“But what about his faults?” I ask.

“Well, he’s sometimes nervous.” I think he means excitable. “And when he doesn’t get what he wants, he becomes angry and makes mistakes. Just like when he was playing basketball!” Tarzan is right next to us, grinning.

We leave soon afterward and drive around the corner to an orphanage that Tarzan and Shamis recently set up. Eighty boys are sitting silently beside a sandy football pitch. Tarzan seems to relax before my eyes. He makes a point of shaking each boy’s hand, and then asks the man in charge, Shamis’s half-brother, Abdi, why they’re just sitting idly.

“They were waiting to pray? But that’s in half an hour. They should be playing, exercising. It’s most important for them at this age.” He turns to me. “Abdi doesn’t understand this. He didn’t grow up in an orphanage.”

We can’t stay for long. And not only for security reasons. Tarzan has just had a phone call about a possible gathering in the city. A rally, of sorts. It’s a rare chance for him to address a local crowd and I can sense his excitement. But as we’re getting back into our cars he gets another call. The crowd is too small. It’s not worth the risk. I suggest we go to one of the cafés on Lido beach instead, but he’s not keen on public places.

“I have to protect myself. If I spend an hour in a hotel, someone will call Al Shabab and say, ‘Tarzan is here.’”

* * *

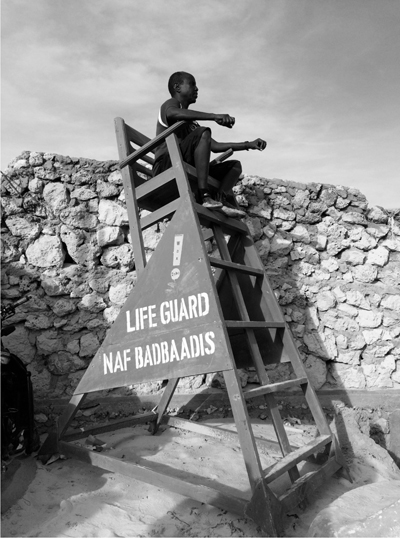

IT’S LATE AFTERNOON NOW and the sun is starting to sink through a clear blue sky behind the city. We drive to Tarzan’s house to drop him off and then head back toward Lido beach. We park on a sand-covered road nearby and walk down toward the surf.

It’s nearly high tide, and the crowds are pressed up close to the rocks on a narrowing strip of sand. I can hear the screams and the laughter, and I think I can already make out a few accents—kids from Wembley and Minnesota, back for the holidays, plunging into the waves.

I stop to talk to an earnest middle-aged man, perched on a homemade wooden lifeguard’s chair, but I’m interrupted, abruptly, by an angry man brandishing a grenade. Perhaps “brandishing” is the wrong word. I only notice the grenade after a few seconds. He’s holding it clenched in his left hand, like a purse. From his behavior, I’m pretty sure he’s been chewing khat. He’s some sort of district security official, and he wants me to leave. The presence of foreigners might, he says, attract Al Shabab. I’ve been through similar drills before, and I make a call to someone senior in the government—an old London friend of Tarzan’s, as it happens—and hand the phone over to the grenade-man.

Ten minutes later, I’m sitting in the shade, on the terrace of the Lido Seafood restaurant, drinking a large glass of fresh fruit juice. It’s Friday, and the place is packed with well-to-do Somalis, men and women, locals and diaspora, in elegant suits and long dresses, mingling and chatting.

Lifeguard, Lido beach, Mogadishu, 2015. COURTESY OF BECKY LIPSCOMBE

I think about Shamis, still in Dubai, trying to make a success of her dress shop. I called her the other day and she sounded overjoyed. She told me Tarzan had promised her that this would be his last year, his last attempt, to get somewhere in Somali politics.

“He said, ‘Give me a chance. If we’re not successful, I’ll stop.’ And we’ll never go back to it, ever,” she added, firmly. But I wonder if she really believes it. Tarzan’s brother Yusuf certainly doesn’t.

“It’s in his blood! In his veins! He’s not going anywhere. If she thinks he’s going to retire, she’s deluding herself.”

But Yusuf wonders if his brother has the flexibility to rise to the very top, or whether he’s too stubborn to make the necessary deals in an increasingly crowded political arena full of people “without principles or qualms.”

And what of Somalia’s own future?

Yusuf used to talk enthusiastically about coming back “home” to Mogadishu in retirement. Maybe even of getting some extra-plump wheels for his mountain bike so he could pedal around in the sand, herding camels back in “our home area” in the countryside. But now he’s not so sure.

Like Yusuf, I’ve always bristled against grand predictions— a favorite hobby of foreigners throughout Africa, anxious to pin their epitaphs to Zimbabwe, South Africa, Nigeria, Mali, or Kenya. The continent is either doomed to fail or rising like a phoenix.

Somalia has slowly begun to make measurable progress. It now has an army and a government. Piracy has almost stopped, Al Shabab controls much less territory, there is oil offshore, a flourishing livestock industry, and a talented and wealthy diaspora.

And yet, the politics are still dangerously messy, fueled by the greed of unaccountable politicians, the fragility of opaque institutions, the enduring menace of Al Shabab, and the questionable ambitions of some regional leaders and of Somalia’s neighbors, Kenya and Ethiopia.

This may no longer be a “failed state,” but the jigsaw is still in pieces.

“I take a long-term view,” says Yusuf, looking for an optimistic vantage point. But Tarzan is resolutely gloomy, convinced that “we’re not heading in a good way, believe me,” and that the decision to carve out powerful new federal states within Somalia will lead the country back toward clan conflict and civil war.

I look out across Lido beach toward the Indian Ocean. A few fishing boats are bobbing in the surf, and above them, a slim jet is roaring northward. In a few months’ time, Al Shabab’s fighters will attack this same terrace from the road and the beach, killing twenty people.

But right now, on a blissfully clear evening, with lobster on the menu and a cheerful, even raucous crowd of Somalis gathered from every corner of the earth, it feels like the worst must surely be over, like pessimism would be a crime. It feels like a homecoming.