It was Sunday morning. Manchester was drowsy and still. And DI Sam Tyler was staring death in the face.

My God …! It’s him …

His blood had frozen in his veins.

Don’t run. Stand your ground.

Sam’s heart was hammering in his chest.

This is it. This is the showdown. Don’t run – be a man – it’s time to finish this thing here and now!

The silent confrontation between him and death had been as sudden as it was unexpected. Sam had been walking through the city on a typically dead Sunday morning. Manchester was lying in, its curtains still drawn, its head under the covers, refusing to budge. Here in 1973, Sunday trading was still just a promise – or a threat – that lay in the future. Apart from a few corner shops and wayside cafes, all the shutters were down. Hardly a car moved in the streets. An elderly man walked his elderly dog. A solitary council worker gathered up discarded cans of Tennent’s and stinking chip papers. And through this, Sam had made his way, lost in his own thoughts.

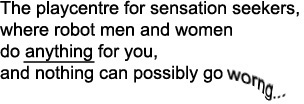

Hurrying past the Roxy cinema, a sudden movement had caught his eye. He glanced up – and at once he gasped and stumbled to a halt. Stepping out noiselessly from the dark façade of the cinema came a shadowy figure, blank-faced and featureless. It positioned itself in Sam’s path, standing motionless in front of a gaudy poster for Westworld, which remained visible through its hazy, insubstantial body. Grotesquely, Yul Brynner’s face – falling away like a mask to reveal robot mechanics underneath – could be seen where the shadow’s own face should have been.

Sam knew at once what – or rather who – that phantom was. He knew the aura of horror that hung about it, had experienced before the primal terror that surrounded this dreadful apparition.

Running a dry tongue over dry lips, Sam said as calmly as he could: ‘So. Looks like you’ve found me, Mr Gould.’

There was no sign of response. Yul Brynner glared back at him through the blank mask of the Devil in the Dark.

Sam tried to pluck up the courage to take a challenging step towards this thing of darkness. But his feet would not obey him. He remained rooted to the spot. Acting tougher than he felt, he said: ‘How are we going to do this? Do we fight? Or do you just zap me with a death ray? Whatever it is, let’s do it. Right now. Let’s finish this.’

Brave words. But he felt anything but brave. A bead of sweat rolled down Sam's face.

The shadow shifted its position, and now, through its hazy form, Sam could see the Westworld poster’s tag-line, perfectly readable through Gould’s chest:

‘Don’t just stand there,’ Sam said, lifting his head and refusing to be cowed. ‘You want Annie? Forget it. You’re not getting her. She’s with me now, you filthy, bullying, murdering bastard. You’re never going to lay so much as finger on her ever again. You and her are history, done with. But you and me, Mr Gould, we have business to finish.’ He raised his fists. They felt puny and weak, like the fists of a child. ‘So let’s get on with it.’

Clive Gould, the Devil in the Dark, remained still and silent, an insubstantial shadow, a dark, hazy stain upon the air. But Sam could still recall the broad-nosed, snaggle-toothed face of Clive Gould from that awful night he had witnessed the murder of Annie’s father, PC Tony Cartwright. In dreams and waking visions, the Test Card Girl had shown him more of Gould’s cruelty, the sickening treatment Annie had suffered in life from this brute, the beatings, the assaults, the psychological torture. And although he had not seen it for himself (thank God), he knew that it was at Gould’s hands that Annie had died. She had died, just as Sam had died, and Gene Hunt and all the rest of them, and wound up here in this strange simulacrum of 1973 that lay somewhere between Life and the Life Beyond.

And at some point Clive Gould died too, Sam thought. But unlike Annie, he shouldn’t have come here. His place was elsewhere. But that hasn’t stopped him. He’s forcing his way into 1973, strengthening his presence here, becoming more and more real. At first, he was a dream, a glimpse of something awful in the dark recesses of my mind. Then I saw him personified in the monstrous body tattoos of bare-knuckle boxer Patsy O’Riordan. Then, in Friar’s Brook borstal, I saw his face, and I saw how he murdered Annie’s father.

And now – right now – I’m seeing him again. A shadow – a ghost.

Sam frowned, tilted his head, thought to himself.

‘You’re not saying very much, Mr Gould. What’s the matter? Don’t you want to kill me here and now? Or is it … is it that you want to, but you’re not strong enough yet?’

The shadow stirred at last. It seemed to push back its shoulders, as if about to attack. But Sam sensed it was all for show.

‘I’m right,’ said Sam, and he felt emboldened. ‘You’re not strong enough to beat me yet. You’re just trying to psych me out before the showdown. You sad, pathetic bully. Well … you might not be ready for this fight, but me …’

Sam lunged forward, hurling a blow at Gould, putting all the weight of his body behind it. He lost his balance and staggered forward, righting himself at once and throwing up his left arm to deflect a counter-attack. But no attack came. The street outside the cinema was empty. Sam stared at Yul Brynner, and Yul Brynner stared back, but of Clive Gould there was no sign.

‘Run if you want to!’ Sam shouted into the empty street. ‘I’m not running anymore! I’m done with running. I’m coming for you, Gould! I’ll find you, and I’ll beat you, and I’ll send you back to the hell you came from!’

His blood was up, he was ready for battle – but his enemy had quit the field. Sam brought his breathing under control and unclenched his fists. He wiped the sleeve of his leather jacket across his glistening forehead. His knees were shaking.

Despite the fear that Gould’s ghost-like appearance had instilled him, Sam felt a strange surge of hope and defiance rising up from deep within him. Gould was getting stronger, but he still didn’t have what it took for the final duel. He would delay the final confrontation until he was more powerful – unless Sam could track him down before then and finish him once and for all.

And I can do it! If I can draw him into a fight before he’s ready for it, if I can provoke him into attacking me too soon … I can do it! I can WIN!

The sense that things were moving towards an endgame between these two implacable enemies renewed Sam’s energies, even revived his spirits. Victory – or at the very least, the possibility of victory – was at hand. The chance was coming for Sam to dispel Gould forever. He had no choice – he had to win this fight; the price of failure was too high. And when he at last defeated Gould, his and Annie’s future together would be wide open, like a shining plain beneath a golden sun, just as Nelson had shown him in the Railway Arms.

‘I’m not here to carry your burden for you,’ Nelson had told him. ‘That’s for you and you alone. Be strong! It’s the future that matters, Sam. Your future. Yours and Annie’s. Because you two have a future, if you can reach it. You can be happy together. It’s possible. It’s all very possible.’

Possible – but not guaranteed.

‘“Possible” is the best odds I’m going to get,’ Sam told himself. ‘Perhaps I can improve those odds with a little help. But who can I turn to?’

At that moment, he stopped, glancing across at a grimy, gone-to-seed, urban church, out of which slow, wheezing music could just be heard. The organist was limbering up before the service. It took a few moments for Sam to place the tune – he hunted through his memory like a man rifling through a cluttered attic – and then, quite suddenly, he found what he was after.

‘Rock Of Ages,’ he muttered to himself. And from somewhere at the back of his brain, words emerged to join with the tune:

While I draw this fleeting breath,

when mine eyes shall close in death,

when I soar to worlds unknown …

‘Something something dum-dee-dum, rock of ages, cleft for me.’

Like photographs in an album, old hymns had a potency that no amount of rationalism and scepticism could entirely stifle. Deep emotions were stirred – part nostalgia, partly unease, part regret, part hope. Sam thought of his life, and of his death – and of Clive Gould emerging from the darkness – and of Nelson, breaking cover to reveal that he was far more than just a grinning barman in a fag-stained pub – and he thought of Annie, whose memory, as always, stirred his heart and gave his strange, precarious existence all the focus and meaning he could ask for.

Despite everything – the threats, the danger, the approaching horror of the Devil in the Dark – Sam felt happy. He knew it wouldn’t last, but as long as it did, he let the feeling warm him, like a man in the wilderness holding his palms over a campfire.

Sam turned away from the church, strolled across an empty street devoid of traffic, and ducked into Joe’s Caff, a greasy spoon which served coffee like sump oil and bacon butties cooked in what seemed to be Brylcreem. There were red-and-white checkered plastic covers on all the tables, bottles of vinegar with hairs gummed to the tops, and ketchup served in squeezy plastic tomatoes. Joe himself was a miserable, bolshy bugger who covered his fat belly in a splattered apron and never cleaned his fingernails. He let ash from his roll-up fall into his cooking, and checked to see if food was ready by sticking his thumb into it.

Sam loved the place.

‘Morning, Joe,’ he said as he strolled in, enjoying his brief inner-glow of happiness. ‘Any news on that Michelin star yet?’

Joe grunted wordlessly back at him. He was shoving meaty objects about in a pan, presumably preparing them for human consumption. From the portable transistor radio balanced above the stove came the strange, melancholy strains of Elton John’s ‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.’

‘I’ll have a skinny Fairtrade latte to drink in please,’ said Sam. ‘And a peach and blueberry muffin, and a bottle of still mineral water. Actually, come to think of it, I’ll go for the deep-fried heart attack and a cup of black stuff so gloopy I can stand the spoon up in it.’

Joe looked at him like he’d spoken in Norwegian, so Sam clarified: ‘The full English and one of your unique coffees; quick as you like.’

A jabbed finger and a grunt told Sam that he was to take a seat, so he settled himself facing the door, waiting for Annie and his breakfast, whichever arrived first. He had suggested meeting her here partly because his own place was such a tip that he was ashamed for her to see it, but mainly because Joe’s Caff was the sort of place that cheered you up. It was hard to stay too depressed when you were pumping ketchup out of a plastic tomato. And it was clear that Annie needed a little light in her soul at the moment. Since the riot at Friar’s Brook, and their close shave with knife-wielding borstal boy Donner, she had become withdrawn and preoccupied. Long-buried memories were returning to her; memories of her life before this one, of her father, of an Annie Cartwright very different from the one she was today. It was all still hazy, but she was starting to suspect that all was not as it seemed here in 1973, and that Sam’s strange stories about her past and her family might be more than just fantasies.

I’m going to explain everything to her, Sam thought, watching the door. It won’t be easy – for either of us – but it’s the right thing to do. And with Clive Gould breathing down our necks, she’s got no choice but to understand.

Through the open doorway, Sam could see the church across the road. The wheezing music had stopped, and a straggle of worshippers was now wandering in. Sam watched the desultory handful of OAPs as they headed through the graveyard and in through the church door. It was a typical Sunday-morning turn out. And yet, the sight of it tugged at Sam’s heart. He was hardly a religious man, but that plain, threadbare, C of E church with its leaky spire and unkempt graveyard and its smattering of a congregation spoke to him of Life and Death, of worlds beyond this one, of higher purposes and plans played out in mysterious ways. It reminded him that 1973, like Lieutenant Columbo, was only a shambling mess on the outside: behind the ruinous façade, wheels were turning, great forces were at work, high stakes were being placed.

‘Ee-yar,’ grunted Joe, and he slammed down a plate of runny eggs, fatty lumps of meat, and fried bread glistening with grease.

‘Is this my breakfast or something you just coughed up?’ Sam asked. And as Joe turned away he added: ‘Hey, before you disappear, tell me – do you know anything about old watches at all?’

‘Wrote the book on ’em,’ said Joe sourly, and he peered down at the gold-plated fob watch Sam had rested on the table. ‘Antique, is it?’

‘I have no idea.’

‘Take it down the market, see if someone stumps up a couple of bob.’

‘I’ve no intention of selling it,’ said Sam, closing his hand protectively around the watch. ‘I’m not parting with him, Joe. There’s something very special about it.’

‘You want to get the case replaced. Looks like somebody’s sat on it.’

‘Nobody sat on it,’ said Sam. He ran his finger over the dent that Donner had made with his kitchen knife when he’d lunged at Sam. It had saved his life once already. Maybe it'd do it again.

Utterly disinterested, Joe plodded back to his greasy pots and pans and joylessly started frying a few eggs.

Annie suddenly appeared in the open doorway, dressed in a wide-collared, canary-yellow shirt under a brown suede coat. She paused and looked in. Sam could tell at once something was wrong. Her face was pale, her eyes wide and anxious. When she sat down across from him, she said nothing, just folded her arms defensively.

‘Hi,’ smiled Sam. But Annie just frowned worriedly at him. ‘You’re very tense. Has something happened?’

Annie shrugged.

Thinking of the shadowy ghost that had confronted Sam outside the cinema, Sam asked anxiously: ‘Have you … seen something?’

‘I’m just not feeling right,’ she said.

‘Are you ill?’

‘I don’t know. I just know I’m not right.’

‘Let me order some revolting food for you,’ Sam suggested. He indicated the congealed filth on his plate. ‘You want to join me in a full English? It’ll take your mind off things. Not in good way, but it will take your mind off things. Go on, have a dip with one of my soldiers.’

But there was no response from Annie. She was not in a joking mood. Now that Sam looked at her more closely, she seemed shell-shocked.

‘Talk to me,’ he urged her gently.

‘I’ve been digging into the old police files from the sixties,’ said Annie.‘I needed some information, but the files were in a mess, so I started trying to sort ’em out, get ’em in order. God knows, nobody else in that place is going to do it.’

‘Well ain’t that the truth.’

‘So, I started going through it all. Everything was all filed badly and mucked about with. At first I just thought it was just the usual thing, people being careless, sticking reports in the wrong folders and not bothering to label things right. But then I noticed there were gaps, Sam – gaps like there were things missing on purpose.’

‘You’re saying those files have been tampered with?’

‘I’m sure of it, Sam. Somebody’s been covering things up.’

Sam nodded: ‘There were a lot of coppers on the payroll of villains back then, far worse than today.’

‘And I think I can name a few of them. There’s the same characters who keep cropping up, all of them in CID, all of them in relation to those gaps in the files or with reports that don’t quite make sense. I’ve got their names.’

She placed a sheet of paper on the table.

Sam read it out: ‘DCI Michael Carroll, DI Pat Walsh, DS Ken Darby. Any of them still serving in CID?’

‘No. They’re all retired now,’ Annie said.

‘The corrupt ones always retire. Mmm – these names don’t ring any bells for me.’

‘Nor for me, Sam. But I wonder if the Guv remembers them?’

It was possible. DCI Gene Hunt must have been working his way up through the ranks of CID at the same time as these men were around.

‘I wrote these names down so I wouldn’t forget,’ Annie went on. ‘But there’s one name I can hardly forget – the name of a uniformed copper working at the same time as these three.’

‘Let me guess,’ said Sam. ‘Cartwright. PC Anthony Cartwright.’

Annie looked at him with wide, confused eyes, and then dropped her gaze and nodded.

PC Cartwright. Annie’s father. Sam had seen him, met him, spoken to him – and then watched him die at the hands of Clive Gould, the villain who had all these coppers and detectives on his payroll. Sam had seen it all, though it had happened ten years ago. He had been there.

Choosing his words carefully, Sam asked: ‘What can you tell me about Anthony Cartwright?’

‘I looked him up,’ said Annie. ‘He was a uniformed officer, quite young. Something happened to him, and he died. I think there may have been some sort of a cover-up.’

‘But the name, Annie. What does it mean to you?’

‘I … I don’t know what it means to me, Sam. When I saw it, I tried to think if I had any relatives with that name. Uncles, cousins. But … I couldn’t think of any, Sam. I mean, I couldn’t think of any, no names at all! I couldn’t remember nothing, Sam! Not me mum’s name, not me dad’s – nobody! I tried, but my mind was a blank. It was like I was going mad.’ Annie ran a hand over her forehead, and let out a shaky breath. ‘I got really scared. But then, looking at the name again – PC Anthony Cartwright – it played on my mind …’

‘Did memories start coming back?’

‘Not memories as such, just … impressions. Feelings. Echoes of things. God, I don’t know, I can’t explain it.’

The same thing will happen to me if I stay here long enough, thought Sam. This place – this 1973 us dead coppers find ourselves in – it takes us over eventually, erodes our memories of the life we used to lead, makes us forget everything except the here and now. But those memories of what we used to be are still in there somewhere – buried deep – waiting to be unearthed.

‘I’m really confused, Sam,’ Annie muttered.

‘Believe it or not, I completely understand you,’ Sam replied.

Annie looked at him intensely: ‘Yes. I think you do. You know things, don’t you.’

‘Yes. I know things.’

‘Something’s going on, isn’t it. Something weird.’

‘Pretty weird, Annie, yes.’

‘Then help me,’ Annie urged him. ‘Tell me why I can’t remember nothing. And tell who you are. And who I am! And where the hell we are!’

Sam hesitated. It was a long story – long and mysterious, and full of things he didn’t understand and dark corners where real horror lurked. Where to begin?

Slowly, he took a deep breath, preparing himself for an explanation he had no idea how he was going to phrase. But he only got as far as one word.

‘Well,’ he said. And then, without warning, he was on his feet, staring past Annie through the open door of Joe’s Caff. ‘Oh my God …’

‘Sam? What is it?’

‘A fella …’

‘A fella?’

‘With a gun. I've just seen a fella with a gun.’

‘What? Where?’

‘Right there! Walking into the church! I just seen a fella with a gun walking straight into that church!’ Sam ran for the door, shouting: ‘Joe! Dial 999! Now!’

Joe stood and gawped, slow-witted as a Neanderthal, so Annie shoved past him and grabbed the phone as Sam raced out into the street. He heard Annie’s voice calling after him – Don’t go, Sam, stay here, wait for back up! – but he couldn’t stop himself. His instincts had kicked in.

Is this the final showdown? Sam wondered as he sprinted across the street and through the little churchyard. Was that Gould I saw? Is he ready now? Is this how we’re going to finish this business between us – in an armed stand-off in a church? So be it, then. If that’s what he wants, let’s do it. Let’s do this thing! Let’s finish it once and for all – right now!

He reached the arched entrance of the church and flung the doors open before he could talk himself out of it.