2

An Artist of the Modern School

When Mignon Toby first encountered Bill Menzies, it was in the old lunchroom at the Art Students League. Though he had a bad complexion and a girlfriend named Debbie, she thought him “cute.” The next time they met was at the 1916 Fakirs Ball, where he was accompanied by a girl wearing nothing more than a coat of blue paint. Again she thought him cute. And this time the feeling was mutual.

Mignon was the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Edward Toby. He was president of Toby’s Practical Business College in Waco, Texas, and Mrs. Nanon Toby was, by her own account, “one of the most successful publicity agents in New York.” (She also wrote features for the New York World and the New York Herald.) When Nan decided her fifteen-year-old daughter had enormous talent, she pulled her out of St. Mary’s, a preparatory academy for girls in Garden City, and enrolled her at the Art Students League, where Mignon would spend the next eight years of her life.

Older and taller than Bill, Mignon wore her dark brown hair in a bob. She was not traditionally beautiful, but she had bright brown eyes, a lovely smile, and a light voice that combined her Texas drawl with the beginnings of a New York accent. She was a good dancer who always had men around her and was forever getting her friends dates. One of her partners was Norman Kaiser—later the actor Norman Kerry—whom she had known since he was right tackle on the Hempstead High School football team. Kaiser’s friend was a taxi dancer named Rodolfo Guglielmi. One day, Mignon got a call from her mother’s boyfriend, a dress extra in the movies, who said they needed some young people for a dance scene and asked if she could round up some friends. She called Kaiser, who asked if he could bring his pal Rudy, and that, according to family lore, was the first time Rudolph Valentino appeared before a movie camera.*1

Clearly, Bill Menzies had a case on her, but the courtship didn’t go smoothly. He always had to have Ade Scharf, a hard-drinking pal from New Haven, along on dates. That didn’t matter much, however, once Mignon discovered that Bill was a “most wonderful dancer.” As dancing was a big part of her life, she soon had him working out a routine based on the tune “Too Much Mustard.” They auditioned for a spot on the Majestic Roof, and, much to their astonishment, got it. “We were offered the job there,” she recalled, “but Mother wouldn’t let me do it.” By the time Billy—or “Billee” as he tended to spell it—enlisted in the Navy, the two were talking marriage.

Plainly scared of Miggie’s stern mother, Menzies put off “the marriage question” as long as possible. Nan begged Edie Smith, her daughter’s closest friend, to scuttle the “horrid match,” but Edie knew true love when she saw it and let Miggie and Bill use her 23rd Street apartment whenever she and her husband, Walter, went to the movies. Bill shipped out to Guantánamo on July 7, 1917, but the time away made his longing all the more intense. “There isn’t any senorita pretty enough to take my mind off you for a minute,” he assured her in a letter, “so don’t put any worry in on that score.” He described his time in Cuba as “fairly active but boring” and began illustrating his letters home with delicate pen-and-ink cartoons of the people of Santiago. “I have been dreaming of you lots down here, sweetheart, and you are always so wonderful after seeing these Cubans.”

On March 20, 1918, Bill, still in uniform, wed Mignon at the place where his own parents were married—the Church of the Transfiguration, an Episcopal parish famously known as the Little Church Around the Corner. A hurried five-day honeymoon in Atlantic City followed, with Ade Scharf on hand for breakfast on the very first morning. Then it was off to Pelham Bay, where, on May 18, Menzies accepted office as a provisional Ensign (D) (Deck Duties Only) in the Naval Auxiliary Reserve. Ensign William Charles Menzies of the Merchant Marine was assigned to the collier Proteus, which cleared port on July 14. “I was one of the worst Naval officers that ever trod a quarter deck,” he later admitted. “I got through Navigation because the instructor had been an extra man and hoped I could help him after the war.” His brother, Ensign John C. Menzies, was stationed at the Naval Air Station in Eastleigh, England. Bill arrived in Glasgow on July 31 and began five months of gun crew duty, shuttling coal between Queenstown, Brest, Poliac, Bordeaux, and, as he put it, “all the usual joints.”

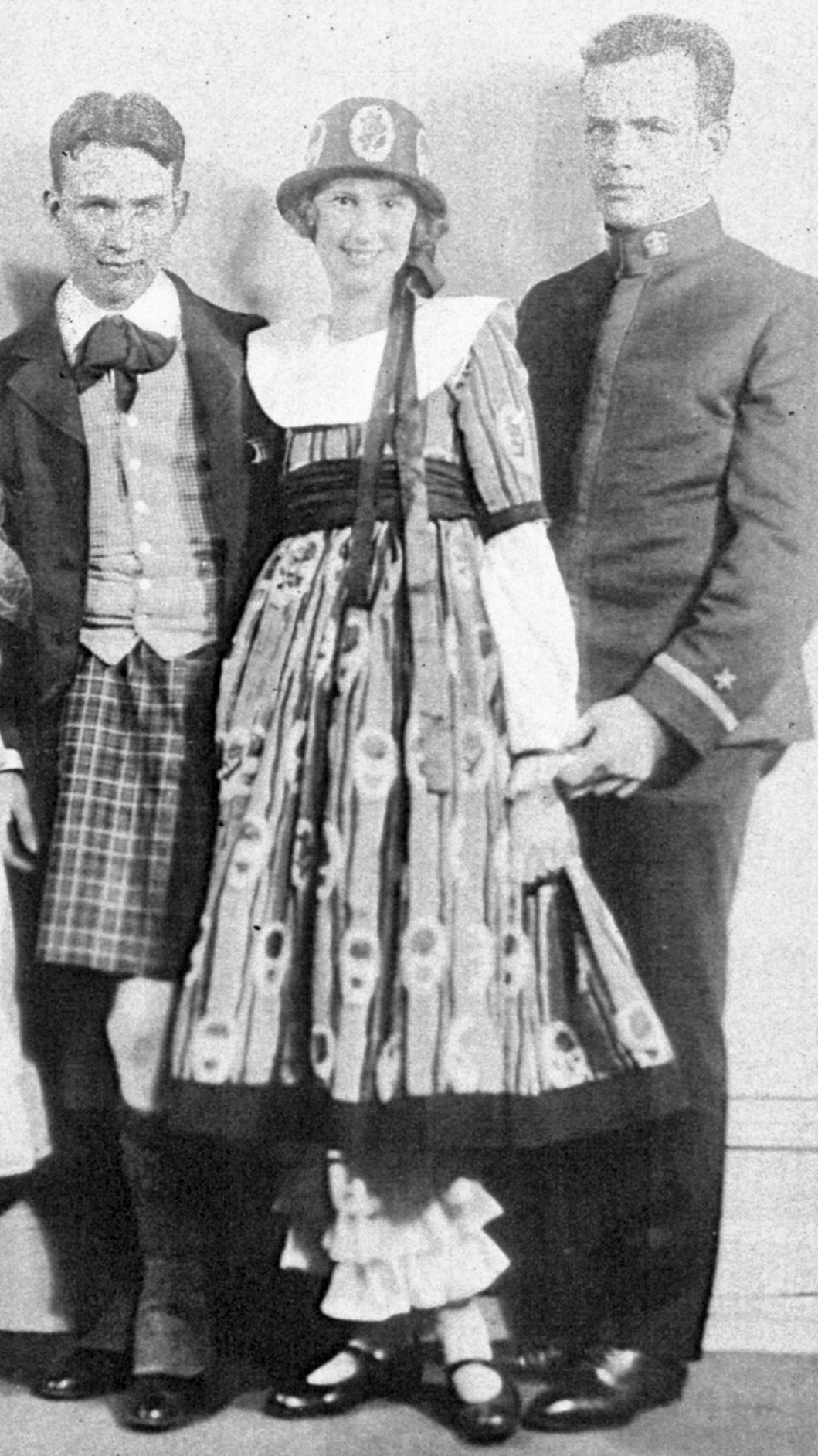

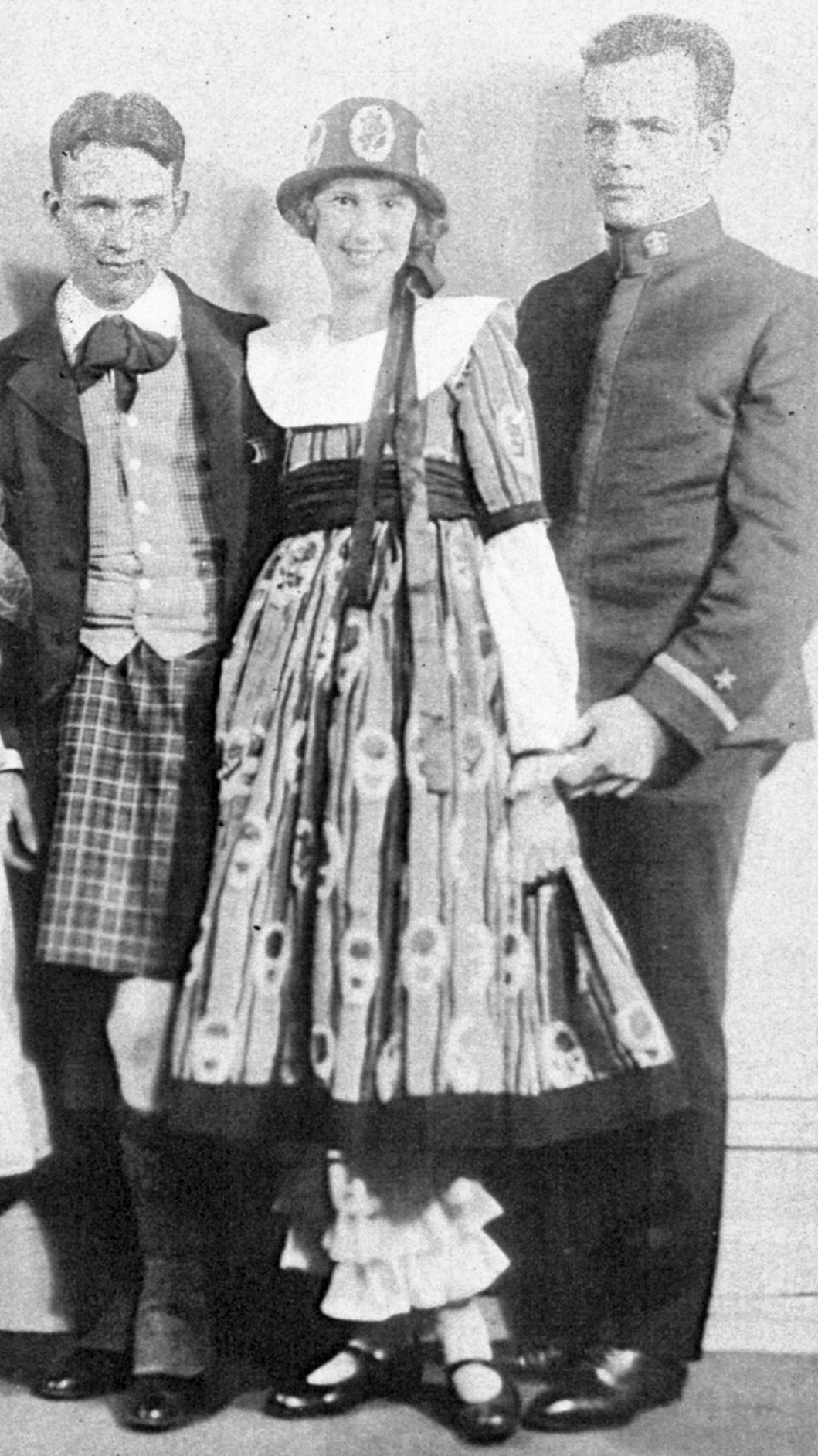

Mignon Toby, circa 1917, flanked by Bill Menzies and his elder brother, John

(MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

Discharged on December 20, 1918, Menzies found himself back in New York with few prospects for work and little money in the bank. Mignon had taken an apartment on West 58th Street, and it was there that they celebrated Christmas. Scouring the agencies—Sherman & Bryan, H. K. McCain, J. Walter Thompson—he landed work as an illustrator, but freelance advertising was a tough way to make a living when clients were famously slow to pay. Mignon, who seemed to know everyone, introduced him to a director named John Robertson at a holiday party. Then Bill ran into George Fitzmaurice at the Aker, Merrill and Condit store, and between the two he was able to get in as a sketch artist at the Famous Players studio, a remodeled riding academy on 56th Street. “My office,” he said, “was an old horse stall covered with tongue and groove.”

Assigned to R. Ellis Wales, an old costume man on his first job as a set designer, Menzies did most of the heavy lifting on a picture for Robertson called The Malefactor. He showed a flair for stylish exteriors, rendering a key garden set in the manner of Maxfield Parrish, with a low wall and cypresses beyond a cloud drop and, on one end of the wall, a huge urn with a peacock atop it. “For some reason the property man couldn’t get a peacock with a tail,” he remembered, “so he wired the tail-less one to the urn and attached a defunct peacock’s tail to the end of it.” The effect was grand, he said, and might have worked too, if the bird hadn’t had more strength than they figured. “Right in the middle of one of [star John] Barrymore’s big scenes, the critter jerked loose from the pedestal, jumped straight at John, bumped him to the floor, and, as a souvenir, left its handmade tail wreathed about the famous Barrymore profile.”

The picture marked John Barrymore’s debut as a dramatic lead after years of playing in comedies. An amateur artist himself, Barrymore was impressed with Menzies’ speed and precision, and the two men became friends. When the film was released in April 1919 as The Test of Honor, it won Barrymore the following of a true matinee idol and got Menzies raised from $60 to $75 a week. By that point, he had graduated to full status as a “technical” director, designing sets for Famous Players at the rate of two features a month.

One of the most elaborate of Menzies’ early sets was this Venetian exterior for A Society Exile (1919). It took up most of the Famous Players studio on West 56th Street, the former home of Durland’s Riding Academy. A foot-deep trough of galvanized iron held the water, while the gondola was moved along the canal on wheels. (ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES)

Much had changed in the two years since Menzies had served his apprenticeship in Fort Lee. Stirred by the compositions of men like Wilfred Buckland (who aspired “to picturize in a more ‘painter-like’ manner”), Joseph Urban, and Ben Carré, audiences had come to expect the best movies to be beautiful as well as dramatic. With a man like George Fitzmaurice, Menzies excelled, rising to the demands of a director who had his own keen eye for tone and composition. By the end of 1919, the critic for Motion Picture Classic, in his review of The Witness for the Defense, would be moved to comment on “the rapidly advancing Fitzmaurice, who attains dozens of singularly beautiful moments and who reveals a surprising knowledge of India.”

Production chief Jesse Lasky took note, and Menzies became an advocate of the “artistic” picture—staging a film with an illustrator’s values. Giving the director an extra measure of artistry kept him in demand, but the process took more time and imagination than straight photoplay architecture. The challenges of properly photographing an intricate set required the occasional building of models. Then there were the practical matters of blueprints and the overseeing of actual construction, a far cry from the practices of a year or two earlier, when sets were often sketched on the backs of envelopes or on the floors of stages. “In fact,” said Menzies, “an early designer of my acquaintance used to design his sets on the palm of his hand if nothing else happened to be handy.”

Fourteen-hour days were the norm at Famous Players, and Mignon saw little of her husband, except on Sundays when he could catch up on his sleep. In the spring of 1919, his productivity and resourcefulness led to an offer from Famous Players executive Albert Kaufman to go abroad to design scenery and train an art department for the company’s new studio in England. The goal of the venture was to exploit “the personality of British artists, the genius of British authors, the beauty and atmosphere of British settings and scenery” while utilizing the technical knowledge of American artists and craftsmen who had advanced filmmaking techniques while England was at war.

Menzies didn’t particularly want to go, but the prestige of the assignment would be good for his résumé, and he stipulated in the agreement that he could not be required to spend more than three months abroad. He negotiated a rate of $100 a week for the duration of the trip and sailed on the SS Aquitania on July 16, leaving Mignon, once again, alone in New York. He arrived in London on the 21st, installed himself at the Kenilworth Hotel in Great Russell Street, and proceeded to set up shop at Famous Players’ Wardour Street headquarters.

Menzies brought characteristic vigor to the assignment, but was discouraged by an utter lack of anything to do. Kaufman’s enthusiasm was premature, considering that even the location for the new facility hadn’t yet been settled. “We spent a miserable winter, as England was still on food rations from the war and the only floor space we could find was the interior of an old power house in Shoreditch.” Plans were announced to make Marie Corelli’s novel The Sorrows of Satan as the first of Famous Players’ British productions, then that gave way to a play called The Great Day, which was presumably selected for the more typically English surroundings it demanded. Yet Kaufman was strangely distant and difficult to see. Menzies took advantage of the lull to visit his grandfather, William Cameron, the greenskeeper at the nine-hole Aberfeldy Golf Club, and his Uncle Alec, who had settled in Northampton.

Though Fitzmaurice wanted him back in New York, Menzies decided the ad game was “really the logical one for me to be in.” The picture business was increasingly political and lacked the security of print work. “I suppose there will be more or less of a job at Famous when I get back,” he wrote Mignon in early November, “but as far as a contract is concerned, I think I would be better off without one, as they can do anything they want with you when you have a contract and it is a handicap if you have other offers.” The new Islington studio was nowhere near being finished when he was sent home—“fired” as he later put it—via the SS Lapland on November 27.*2

Back at 56th Street, he contributed to Robertson’s production of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, in which Barrymore was playing the dual role, and took over work on an Alice Brady subject called Sinners. Watching his salary shrink back to $75 a week wasn’t good for his morale, and he was more than receptive when director Raoul Walsh offered to double his rate within a week of his return. A sometime actor who had made his name directing pictures for William Fox, Walsh was going independent with a remake of the Wilson Mizner–Paul Armstrong crime melodrama The Deep Purple. He and Armstrong were old friends, Armstrong having been responsible for Albert E. Walsh changing his name to Raoul when the two were a pair of struggling actors. Walsh’s wife, actress Miriam Cooper, was set to play the female lead, and Vincent Serrano, a prominent New York stage actor, was to appear opposite her. Funding was coming from the Mayflower Photoplay Corporation, established so directors Allan Dwan and Emile Chautard could make their films in relative autonomy. “Mayflower,” said Cooper, “believed that if it had a good director and gave him a free hand, he’d produce good films.”

Menzies joined Mayflower on December 15, 1919, and moved uptown to the Biograph Studios. Freed from the grind of production at Famous Players, he suddenly had the luxury of time to give the old story some gloss and excitement, the film culminating in a flashy cabaret sequence featuring the specialty dancer and Ziegfeld star Bird Millman. The Deep Purple took on the look of a major studio production, but Menzies’ sets may also have contributed to the static nature of the picture. (“You don’t run past a beautiful picture in an art gallery,” the reasoning went. “You stop and gaze at it.”) The film was unnecessarily episodic—more tableau than driving narrative—and failed to score with either the public or the critics.

Chastened, Walsh gave his wife a choice of material for their second Mayflower production. “It was the last thing Raoul would have chosen,” she said. “I had read William J. Locke’s The Idols and gone completely crazy over it. It was a woman’s story, a soap opera if there ever was one. Raoul had it adapted for me and changed the name to The Oath.” The story of a rich Jewish girl who marries a ne’er-do-well Christian playboy, The Oath gave the dark-eyed, white-skinned Cooper one of the meatiest roles of her career. No expense was spared in production or cast. (Actor Conway Tearle was paid $2,500 a week—twice as much as Cooper was getting—to play the supporting lead.) Menzies’ lavish settings suggested a world of cold opulence, and Walsh staged the action in stark contrasts of blacks and whites. “There is a fineness of light and shade and real dramatic fire in moments of emotional intensity,” said the review in Variety. Again, the film flopped miserably at the box office.

In between the Walsh productions, Menzies was lent to other producers. Still, he was carrying just a fraction of his former workload, and finally the time had come to start a family. In the spring of 1920, just as The Deep Purple was opening in New York, Mignon discovered she was pregnant. The baby was due in early November—when Bill would be deep in production on The Oath—but eleven days late, causing Miggie to spend two anxious weeks at Lenox Hill Hospital “in a lovely large room all to myself” awaiting the birth of their daughter, Jean.

The failure of The Oath helped drive Mayflower out of the picture business. Producers were moving to California, where costs were lower and exteriors plentiful. Walsh formed R. A. Walsh Productions, entered into a distribution deal with Associated First National, and decamped to Los Angeles, where he took offices at the Brunton Studios on Melrose Avenue. Menzies briefly considered going back to Famous Players, which had built a spacious new studio on Long Island, but had grown too accustomed to the leisurely pace of Walsh’s working methods. He followed, unhappy at leaving the theaters and art galleries of New York City, but seeing no alternative if he wanted to advance his career in pictures.

“Los Angeles, then as now, was the town of conventions,” he wrote in 1945, “and there was a Woodsman or an Elk or a Shrine convention going on, and the only room I could get was in a rat-race hotel on Main Street. About the second or third day in Los Angeles, I went out to the old Lasky Ranch to pick a location. Very few roads were paved, and I wore a dark Oxford gray overcoat, a blue serge suit with a starched collar, black shoes, and a bowler. (The New York uniform of the day.) In no time, I was from head to foot the color of adobe before they whitewash it.” When Mignon and Jean arrived in Hollywood on April 26, 1921, he was hard at work on a story of romance and revenge in old Spain titled Serenade. It was a family affair for Walsh and his wife, with Miriam appearing opposite Raoul’s brother George and her brother Gordon serving as assistant director.

Having never been west of Fort Lee, Menzies stuck to his usual routine of referring to books on the architecture of foreign locales, cheerfully exaggerating the characteristics of native design in service of the drama.*3 For Serenade, he could also draw inspiration from the Spanish architecture that dominated the city. Production commenced with key scenes being shot at Mission San Fernando. Cooper loathed working with her Irish brother-in-law, who was sporting an improbable black wig for his role as a Latin lover. “I always dreaded a scene with George,” she said. “He was such a lousy actor. He was like a stick.” Serenade had the production values of Walsh’s previous independents and—despite George Walsh’s wooden performance—received generally good reviews. It was, in Cooper’s words, “most profitable.”

Emboldened, Walsh bought the rights to a best-selling Peter B. Kyne novel called Kindred of the Dust. An action-packed tale of lumbermen in the Pacific Northwest, it was new stuff to the creative team, with a couple of elaborate fight scenes and an underwater effect leading up to the finale. With too much time on his hands, Menzies may have been guilty of overdesigning the picture. Though the book had been distilled to its essentials, an early review complained that Walsh “tried to encompass too many of the interesting details” and that got in the way of the story. “The director has carried to great lengths the practice of allegorically visualizing the poetically descriptive subtitles.”

Kindred of the Dust was previewed in January 1922, but by then it was apparent that Walsh would be making no more pictures as an independent. “Raoul was no businessman,” Miriam Cooper explained. “He was a capable, hard-working director with a gambling streak who wanted to be a big wheel in the industry, and that was all. As an independent producer he’d been lucky in good times, but in bad times he, like most others, was squeezed out of business by the high moguls with their big companies and theater chains. R. A. Walsh Productions had no capital to make new pictures—we’d spent it—and no chain of theaters to show them in if we made them. Our distributor, First National, was in trouble, too. And so our company just died.”

Locked in a secret marriage with a man of a different faith, Minna Hart is beset by trials that culminate in the murder of her father. The brittle symmetry of this bedroom interior is violated by the forlorn figure of actress Miriam Cooper. The last of Raoul Walsh’s Mayflower productions, The Oath (1921) was spread over three New York area studios, including the Solax in Fort Lee where Menzies got his start. (ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES)

Walsh eventually returned to the security of Fox, and Menzies was left—with a wife and a year-old daughter—to fend for himself in Los Angeles.

Bill Menzies expected to land work with another independent when Raoul Walsh closed shop, but he was largely unknown in Los Angeles and his two principal patrons, George Fitzmaurice and John Robertson, were still based in New York. Having given up on the agencies when asked to illustrate an ad for a catarrh remedy (“Do you hack and spit?” the headline inquired), he telegraphed Walsh for help. Headed east on the California Limited with Kindred of the Dust, Walsh complied with a letter of introduction to his friend Douglas Fairbanks: “This will introduce Mr. W. C. Menzies, my art director for the past two years. Our association has been at all times pleasant and artistically successful. He is an artist of the modern school and thoroughly understands the technical requirements of motion pictures. I can recommend him most heartily.”

The letter got Menzies in at the new Pickford-Fairbanks Studio, where its male proprietor was preparing an elaborate take on the Robin Hood legend. Fairbanks had made a name for himself in lighthearted comedies, but was now sustaining his position as a top draw with a series of increasingly costly costume adventures. Showcasing his enormous charm, effortless athletic prowess, and outsized sense of humor, Robin Hood was to outdo The Mark of Zorro and The Three Musketeers in size and spectacle. Accordingly, the art department had been built up to include Edward Langley, Irvin J. Martin, and Anton Grot under the supervision of Wilfred Buckland. This extraordinary team created some of the largest sets ever built for a motion picture. Exactly what Menzies did on the picture is unknown, but he was most likely put to work as a sketch artist, a considerable comedown after the on-screen credits he had earned with Famous Players and Walsh. In later years he declined to include it on his résumé.

Nevertheless, Robin Hood ensured that he was present on the lot when Mary Pickford started work on an equally ambitious costume picture titled Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall. At the age of thirty, America’s Sweetheart had grown tired of playing adolescent girls and hired the great German director Ernst Lubitsch to guide her “farewell to childhood.” She expected Lubitsch, with equal gifts for epic and farce, to impart an air of sophistication she had never before displayed on-screen. Lubitsch then went her one better by proposing instead that she play Marguerite in an adaptation of Goethe’s Faust.

Although no more alienating a subject could be imagined for Pickford’s largely female audience, she went along with the idea to the extent of importing Sven Gade, a Danish stage designer whose startling film version of Hamlet with actress Asta Nielsen had taken Europe by storm. Gade began work on the sets, but when Pickford’s influential mother, Charlotte, discovered that the plot called for her daughter not only to give birth to an illegitimate child, but to strangle the baby in a key scene, the star of Poor Little Rich Girl and Pollyanna was compelled to drop the idea. Menzies was quietly put back to work on Dorothy Vernon so as to make the switch a virtual fait accompli upon Lubitsch’s arrival.

A late display ad designed by Menzies for the Los Angeles furrier Willard George, a pioneer in the importation of chinchilla pelts. Under the slogan “We search the earth for furs of worth,” George became a leading supplier to the movie industry. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

Lubitsch, accompanied by his wife and an associate, landed in Los Angeles in December 1922. Pickford sprung the change on him and, predictably, he loathed the idea. After reading the script, a romance set in England in the days of Great Elizabeth and Mary Queen of Scots, he hated it even more. “Der iss too many qveens and not enough qveens,” he complained, wondering how Pickford’s modest character could make any impression amid the size and grandeur of the thing. He announced that he would not direct Dorothy Vernon under any circumstances, but Pickford, rather than giving him a release, proposed a compromise: Edward Knoblock’s adaptation of a French play called Don César de Bazan, retitled The Street Singer. From his earliest days with Fitzmaurice, Menzies had excelled at exteriors. His rooms were straightforward examples of set design—competent, workmanlike—but he was constrained by the conventions of three walls and contemporary decor. It was the play of light and dark and the shifting of the elements that inspired him, and Gade, who got all the attention and most of the credit, was content to leave him to the details of Toledo and Seville in the days of the carnival.*4 With more money at his disposal than ever before, the Spain Menzies distilled from books and clippings was larger, brighter, more imposing than the real thing, a world that sometimes dwarfed its star, whose director seemed more interested in the romantic plottings of the king than the affairs of a tax-protesting street singer. Nevertheless, Menzies proved equal to the scale Pickford demanded, and the sets, by the account of The New York Times, elicited “murmurs of admiration” at the film’s premiere. Indeed, Menzies found enough satisfaction in the experience to claim Rosita (as the film came to be known) as one of his credits. He particularly relished the experience of working with Lubitsch, who, he later said approvingly, “told his farce with the camera” rather than with titles.

Around this time, Menzies adopted the middle name of Cameron, which he thought would look better on the screen. In the four years since his return from the war, he had contributed to some twenty-five movies, creating settings that ranged from the canals of Venice and the casinos of Paris to British India, the Old South, and Victorian London. His mastery of craft was beyond question, but artistically he was unsatisfied, confined as he was to producing backgrounds for actors, where the drama was served mainly by pantomime, and mood was more a function of lighting than design. The best experiences came with men like Lubitsch and Fitzmaurice, who understood the physical values of a scene and invested their films with texture and nuance as well as histrionics. He longed for the opportunity to make an American picture filmed with European values, in which graphic design was integral to the storytelling process.

Miraculously, he was about to get that chance.

The town of Seville under construction on the backlot of the Pickford-Fairbanks Studio for Rosita (1923)

The completed set with the weight of the centuries upon it. A miniature conceals a nearby stage and continues the illusion of distance to the famed bell tower of the Seville Cathedral. Although Sven Gade posed for stills showing the model of this set to Mary Pickford and Ernst Lubitsch, Menzies placed these photos in his personal album and was presumably the actual designer. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

*1 The film may have been The Quest of Life (1916), which featured Maurice Mouvet and his dance partner Florence Walton. Whether it constitutes Valentino’s film debut is a matter of conjecture. Valentino biographer Emily Leider suspects he was in Vitagraph’s My Official Wife, which was made two years earlier. His first confirmed appearance is in the 1916 Famous Players production Seventeen.

*2 Menzies later learned that when Famous got serious about an English studio, Lasky demanded that he be sent abroad to carry on “the Lasky ideas of settings.” In 1924, the studio Kaufman and Menzies established in Poole Street, Hoxton, in the London borough of Hackney, became the home of Gainsborough Pictures.

*3 As Anton Grot once said, “I aim for simplicity and beauty and you can achieve that only by creating an impression … the set must be so designed as to blend with the spirit and the action of the picture.”

*4 Both Pickford and Fairbanks insisted on authentic costumes and settings for their pictures, but Menzies learned there was such a thing as too much authenticity when he included the campanile of Toledo in one of his early sketches. “Madison Square Garden in New York [had] copied this campanile, and so many people recognized it and asked what Madison Square Garden was doing in the picture that I had to change it.”