3

The Thief of Bagdad

The films of Douglas Fairbanks were not so much written as assembled—acrobatic set pieces strung together with the barest shadings of plot, all in service of the trademark Fairbanks personality. They were energetic, high-concept period pieces, for their time the most expensive star vehicles ever made. Fairbanks scrimped on nothing, knowing that size and splendor had become part of the franchise. He was planning to follow the pageantry of Robin Hood with an elaborate pirate picture, a significant jump-up in scale if not imagination, and preparations for one were very nearly complete when he strode into a staff meeting one day and said, “Let’s do an Arabian Nights story instead.”

Having grown a special head of hair for the pirate role, Fairbanks had gone sour on the plot. Exactly what got him excited about the Arabian Nights is a mystery, but he was known to have purchased the American rights to Fritz Lang’s Der müde Tod (The Weary Death, aka Destiny), and it may well have been that film’s Bagdad sequence, with its brief story of an infidel who loves a caliph’s sister, that inspired him. He had, in fact, been tinkering with such a story when director Allan Dwan first sold him on the idea of Robin Hood.

Typically, Fairbanks immersed himself in research before going forth on an idea, first sketching the rough elements of plot on the back of an old envelope, then talking it over with a small circle of advisors that included playwright Edward Knoblock, scenario editor Lotta Woods, and his brother Robert. Distilling their input as well as his own thoughts, Fairbanks then hired a writer to draft a treatment—no more than a few thousand words in length—that would form the nucleus of a script. The patchwork nature of the process led to the common writing credit of Elton Thomas—meaning Fairbanks and the collective members of his production staff.

Fairbanks had gotten as far as an outline on his Arabian Nights story (which bore some resemblance to Knoblock’s 1911 play Kismet) when he began looking for a gimmick, something to propel his character and, therefore, the action. He found it in a quatrain from Sir Richard Francis Burton’s literal translation of the Arabian Nights:

Seek not thy happiness to steal

’Tis work alone that will win thee weal.

Who seeketh bliss sans toil or strife

The impossible seeketh and wasteth life.

Fairbanks condensed this to the story’s simple four-word moral: Happiness Must Be Earned.

As work on Rosita wound down, it was impossible to ignore the swirl of activity generated by Fairbanks’ new, as yet untitled, picture. “He was dickering with a lot of high-powered illustrators and painters,” Menzies recalled. Pickford’s costume designer, Mitchell Leisen, urged Fairbanks to let Bill Menzies do for Bagdad what he had done so adroitly for Seville, but Fairbanks, who had referred Menzies to Wilfred Buckland on the strength of Raoul Walsh’s letter and then forgotten all about him, spent just enough time with him to conclude, as Fitzmaurice had five years earlier, that Menzies was, at the age of twenty-seven, too young for the job.*

Leisen and Knoblock talked Menzies into making some sample drawings to show Fairbanks, and he immersed himself in the project over a long sleepless weekend. “He worked and worked on those paintings day and night,” Mignon recalled, “then he asked for another appointment. He went over carrying all those drawings on his head because they were heavy, and he walked into Douglas Fairbanks’ office with these boards balanced on his head and said he’d come to show him that he wasn’t too young.”

What Fairbanks saw bore little resemblance to what most art directors produced at the time. Instead of presenting empty rooms of charcoal or crayon, Menzies had approached the subject as if he were illustrating a storybook, rendering Bagdad in ink and vibrant watercolors and placing Fairbanks’ muscular character in the center of each scene. Moreover, the boards were huge—20 × 30 inches—and finished to the edges. Standing before them, it was easy to be engulfed by the images, their depth and imagination, and hard not to be transported to a fantasy world like no other. Fairbanks, said Leisen, “flipped over them.”

Fairbanks had likely seen Edmund Dulac’s Art Nouveau illustrations for Laurence Housman’s retelling of Stories from the Arabian Nights, a 1907 edition that included the tales of the magic horse and the princess of Deryabar. Never, however, had he seen such imagery blown up to such a commanding size. Menzies, too, had likely seen and been influenced by Dulac’s intricate drawings, but while Dulac’s color renderings conveyed character and an extraordinary sense of detail, they lacked the dark tones and fluidity of movement that came so easily to Menzies’ best work. Here were not just scenes from a book, but cinematic ideas conceived and intended for the relatively new medium of the motion picture.

With Menzies’ visualizations as inspiration, the writing of the script accelerated. By April of 1923, when Rosita was still in production, Fairbanks could describe the film to a reporter in considerable detail: “I am going to make the story of the thief of Bagdad, who loves the Caliph’s daughter and then finds that the thing he wants most in all the world is the thing he cannot steal or gain by chicanery.… It will, I think, have a wider appeal than anything I have ever done. For the children, there will be seeming magic; for the artist, beauty; for those who seek merely entertainment there will be a swift-moving plot with mystery and suspense.”

Bolting from the room, Fairbanks returned momentarily with Knoblock, who was at work on the scenario in an adjacent office. Between them, they carried a portfolio of Menzies’ images. “Look at these,” Fairbanks enthused, arranging the boards along an office wall. What the reporter saw were “large scenic drawings of startling beauty and originality. One showed the gateway to Bagdad, another a street scene. There was a drawing for a set at the bottom of the sea, another for the bedroom of the Caliph’s daughter, showing the thief crossing a long bridge which leads into the moon-flooded chamber.… If the plans of the artist and of the star are carried out with fidelity, the remarkable settings of Robin Hood will be entirely eclipsed and a new standard for beauty of lighting effects will be set.”

Fairbanks went on to describe such visual effects as a winged steed and a magic carpet, both appropriated from Lang. “Three princes will be contenders for the hand of the Caliph’s daughter, but this daughter will love the thief. The Caliph will promise his daughter to the suitor who brings the most priceless gift.… There will be ten or twelve reels to this film, and every one will be packed full of fancy, glamour, beauty, and a novel plot. The time and location—Bagdad at the height of the glory of the Caliphate—will give an unexampled opportunity for splendor of costumings and backgrounds.”

Driven by the seemingly endless stream of visualizations from Menzies’ fertile imagination, Knoblock delivered a scenario as thick as the Manhattan directory. Fairbanks seemed to sense they didn’t have fourteen reels of script so much as fourteen reels of art direction. “If we don’t find a way to defeat that thing,” he said, pointing to the massive document as if it were a bomb set to go off, “it will defeat us by its sheer magnitude.” He ordered the picture charted from start to finish, detailing the sets and their corresponding action on a scene-by-scene basis, then had the results blueprinted and posted on the walls of his office, which began to take on the look of a war room. Work on the great city of Bagdad would take the longest and would have to start first.

Fairbanks put Menzies in charge of the art direction for Thief of Bagdad, but kept him under the watchful eye of Mitchell Leisen, who was a bit younger than Menzies but knew how the boss liked to work. “I designed the costumes in keeping with Bill’s sets,” Leisen recalled, “and sort of supervised Bill. All of his drawings went over my desk for approval, and I looked on at the construction of the sets. The art director, the set dresser, the costume designer—we all worked together as closely as possible.”

As art director, Menzies was charged with overseeing a team of eight associates that included Harold Grieve, Park French, and his old mentor, Anton Grot. Scores of pen-and-ink drawings were made to augment the big color boards, and Fairbanks soon had most of the film in sketch form posted alongside his wall charts. Then detailed models were made of the key sets from which templates could be cut and “scaled up” to the actual size of the set. Pre-visualizing the film became something of an obsession for Fairbanks, and as sets were being erected and test shots made, he was known to shut down arguments by simply bellowing, “To Hell with your perspective—photograph ’em just like the sketches!”

“We worked night and day,” Knoblock wrote.

As the sets began to rise up they caused so much comment and admiration throughout Hollywood that visitors from all the other studios kept dropping in to gaze at them in astonishment. The workmen themselves became so keen on their job that when they were taking down the scaffolding of one of the vast buildings, and a new shift of men arrived to take over, the first batch were determined on completing the task so as to be “the first to have a look.” The second batch of men insisted on their right to work. The two almost came to blows and finally reached agreement by finishing off the job together. There’s enthusiasm for you if you like—the right sort of stuff with which to produce a successful picture!

The sprawling Bagdad set under construction in Los Angeles. For a sense of scale, note the worker at the base of the stairway. (ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES)

As the city of Bagdad was taking shape atop some four acres of concrete slab, Fairbanks lamented the ghost gray minarets and keyhole archways and spider balconies. “Those things are anchored to earth,” he said. “There’s nothing ephemeral about them and we’ve got to find a way to lift them up.” Menzies’ solution was to scrap the intricate painting of stonework he originally planned for the foundation, and to instead have the concrete covered with black enamel buffed to a high gloss. Magically, the structure acquired a weightlessness that at last suggested the whimsy of the original paintings. And in the new test shots, the elevations pierced the heavens.

Fairbanks indulged Menzies’ zeal for towering interiors by constructing a special stage to contain the boudoir of the Princess, a set that required sixty feet to clear the grid. “The only times we used that stage again,” said Menzies, “was when we played badminton.” Fairbanks’ insistence on absolute fidelity to the drawings led to a genuine pen-and-ink effect on film. The physical structures were all black and white and silver with an occasional accent of gold, and the shadows they cast were as key as the spaces they created. Menzies had the insides of the arches blackened to force the perspective; even trees were painted black.

The chamber of the Princess incorporates a sweeping staircase that leads to her domed and canopied bed. The splendor of the room makes it the ideal starting point for a great adventure.

(AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

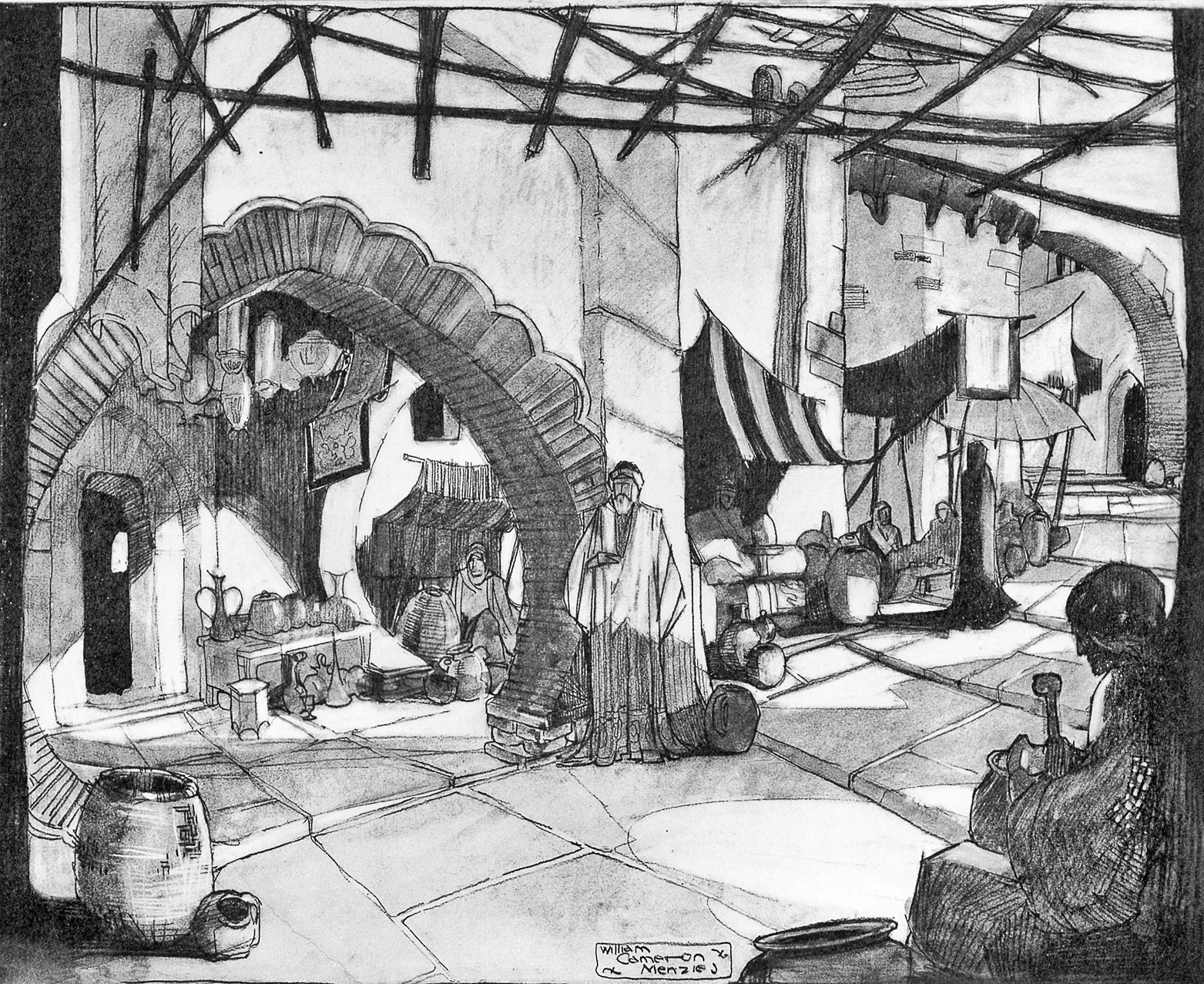

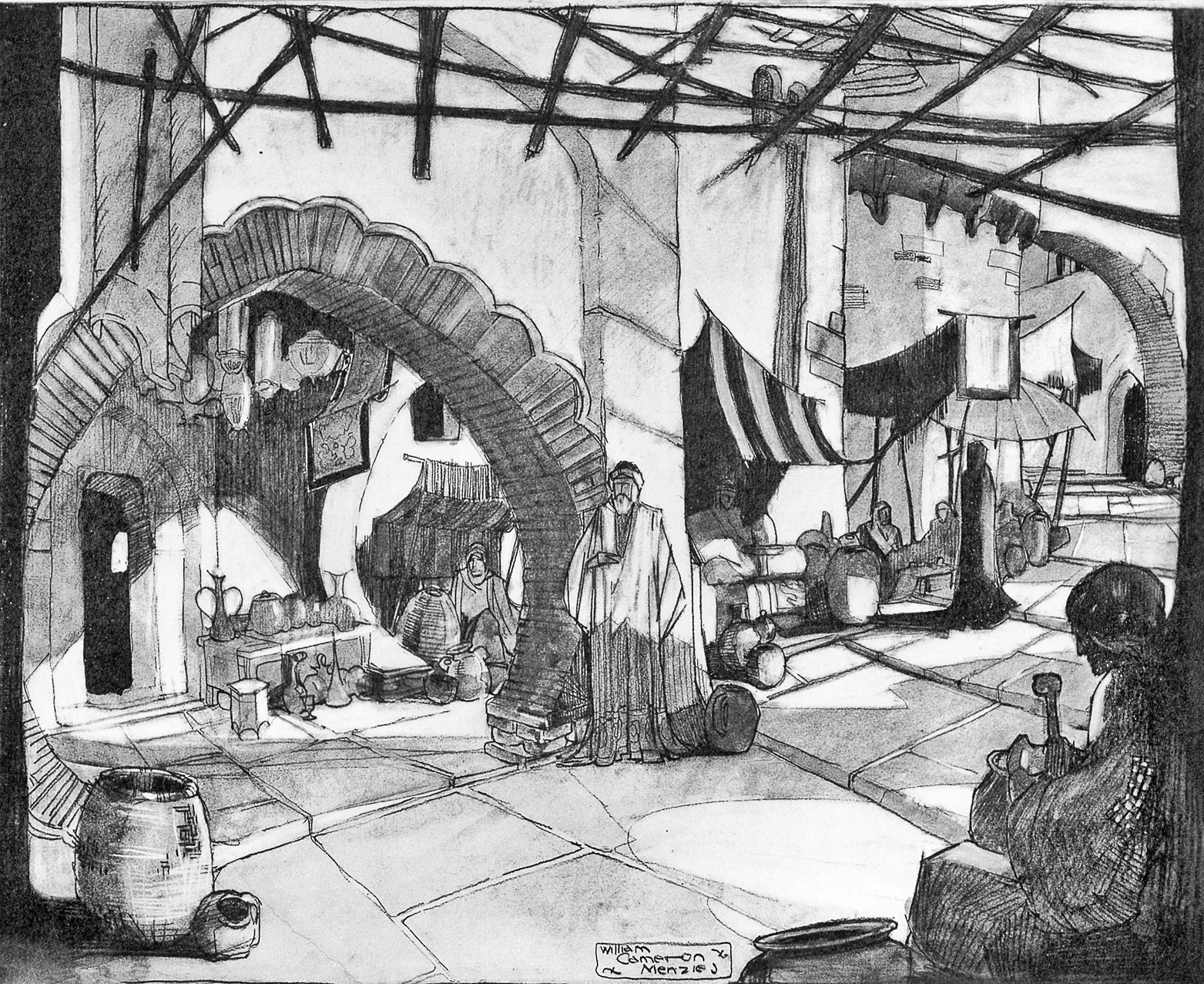

“Here we just played with shadows,” Menzies told a visitor as they strolled the latticed bazaars of Shiraz, where the Persian Prince in the story comes in search of treasure. “You can see what the result might have been.… Walk through that set. You get a thousand penciled designs, different at every turn. It beats costume. See what we did to those posts? That gives the pen-and-ink effect we strove for. It will photograph like a drawing.”

With construction well under way, Fairbanks made the decision to hire Raoul Walsh to direct the film. Under contract to Fox, Walsh was somewhat mystified by the offer, having specialized for so much of his career in “cowboys and gangsters and pimps and prostitutes.” It was apparently his early handling of Tom Mix that got Fairbanks’ attention, along with the devoted salesmanship of Walsh’s agent, Harry Wurtzel. Still, when Walsh went to discuss the project with Fairbanks, he began by saying, “I’m not sure about this, Doug.” Fairbanks cautioned him to hold his reservations. “He took me out back and I caught my breath when I saw the sets.… [Bill’s] artistry was great enough to convince me that I was walking the streets of old Bagdad.”

Walsh signed on and embarked with Fairbanks on a daily training regimen that included a brisk half mile jog around the sets rising on the backlot. “When he brought the script home,” recalled Miriam Cooper, “I couldn’t believe the size of it. It was enormous. Everything was worked out to the last detail. ‘I guess you won’t be writing what you’re going to do tomorrow on the back of some scrap of paper,’ I said. ‘Hell, no,’ Raoul said. ‘These guys put charts up on the wall telling you what to do each day.’ ”

For the bazaars of Shiraz, Menzies covered the walkways with latticework. In striving for shadow effects, he proposed to show the top of the set as well as the floor line. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

The filming of The Thief of Bagdad stretched on for months, a constant flow of visitors and masses of extras delivered by the adjacent Pacific Electric line. “The daily audience appeared to put more snap into Doug’s performance,” Walsh observed, “and he kept his brother Robert, the production manager, busy herding newcomers onto the set to gasp and applaud.”

Production was slowed by Fairbanks’ dogged insistence that every shot be as identical to its corresponding sketch as humanly possible. As Leo Kuter, who worked in the art department, remembered,

Models of all principal sets for The Thief of Bagdad (1924) were built so that Douglas Fairbanks could confirm their fidelity to the artwork. Here he examines the Cavern of the Enchanted Forest through a special viewfinder that shows what the camera will see. Menzies, meanwhile, points out the details. (MENZIES FAMILY COLLECTION)

We used to trace them on glass with wax pencil—set up the glass on the stage or back lot between the set and the finder on a securely anchored camera tripod—just so Doug could take a look and satisfy himself that Menzies’ artistry on paper had taken shape in the actual construction of the set. The sketches, in fact, were photographed and copies distributed to the cameraman, electrician, and all others concerned to make sure that no facet of light, mood, or decorative treatment shown in the sketch should escape reproduction on the screen. Woe be unto the hapless soul who undertook to shift that well-anchored tripod the least fraction of an inch after Doug gave his approval.

Design influenced every aspect of the film—acting, writing, direction, cinema-tography. Leisen’s costumes, all flourish and ornamentation, read perfectly against the clean lines and towering simplicity of the Bagdad sets. Fairbanks himself, clad in the billowing trousers and slippers of the Thief, was, at a trim 150 pounds, so ideal a physical specimen that he immediately became part of Menzies’ fantasy world. The sets were sized to facilitate his spectacular stunts, with distances carefully calculated so that any reach or leap by the star would appear effortless on camera. It was as if a man had wished himself Alice-like into the pages of a storybook, jumping from one illustration to the next, conquering all obstacles and slaying adversaries as if borne on a cloud, destined for immortality.

With its undulating features and irregular surfaces, the Bagdad set seemed as if caught in motion. It challenged Fairbanks and his cast to rise to the standard set by the film’s fanciful architecture. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

To a journalist visiting the set, Menzies paused at a jumble of walls to emphasize how integral the surroundings were to the action. “Fairbanks, in his character of the Thief, smells food cooking up there,” he said, pointing to an esplanade.

He sees a fat man asleep in that corner. Steals his turban. Ties one end to the tail of a passing donkey and throws the other end over the balcony rail. Then he boots the donkey, which runs away, pulling Doug aloft to a footing on the balcony.

The Thief steals the food and leaps to the next balcony. He is pursued by the angry housewife. Meanwhile, a fakir below is performing the rope trick. He has thrown the rope into the air, where it remains rigid, without any support, to the astonishment of the crowd. The end of the rope sticking up there is within reach of Doug’s hand. As the housewife makes for him, he seizes it. Just then, the muezzin calls to prayer from that minaret. Everything stops and the devout Moslems in the street below prostrate themselves. Down comes poor Doug with a thud in the middle of them.

Menzies paused a moment to marvel at all he had been allowed to do. “I don’t suppose I’ll ever get a chance like this again.”

Fortunately, Raoul Walsh understood how the actors could play off the sets. He populated the palace courtyard with hundreds of Mexican extras clothed to look like Arabs, and embellished the action so the film wouldn’t turn into a static showcase of visual splendor. “The rival princes got more than the script called for,” he admitted. “Toward the end, I had them running all over the palace searching for the impostor and demanding his head on a platter.” Not all of the re-creations were entirely successful, given the flat presentational style that naturally resulted from such fidelity to the illustrations. Menzies’ moody visualization of the Cavern of the Enchanted Forest (“a sort of steal from Doré”) resisted all efforts to replicate the depth and mystery of the original, and no amount of articulation could keep a giant bat from looking exactly like the plush animal it was. But when the Old Man of the Midnight Sea sends the Thief underwater in search of an ironbound box containing the key to the Abode of the Winged Horse, the ingenuity of a mechanical engineer helped create the superbly effective illusion that resulted on-screen.

“We took a set and cut seaweeds out of buckram and had a series of them hanging down in several places,” Menzies explained. “A wind machine was put on so that the seaweeds flapped, but as the scene was taken in slow motion, they undulated when shown on the screen. The camera had a marine disk over the lens and was turned over. Mr. Fairbanks was let down into the scene and went through the motions of swimming underwater. The scene had the appearance of water and gave almost a water feeling. It was a very interesting effect.”

Overcast weather impeded filming of the exteriors, and after some seventy days of shooting, the love scenes, the Oriental feast and festival, the spectacle of the Chinese prince’s army capturing the city, and the Thief’s triumphant return to Bagdad were all still to be done. The most challenging of the remaining effects was the Thief’s climactic escape aboard a flying carpet. Merely putting the carpet and its passengers in front of a rolling background wouldn’t do for a film that had already exhibited unprecedented scope and sophistication. The answer finally came to Walsh while observing a construction job at Hollywood and Highland: “The steelworkers were topping out, and one of them was riding a load of girders up from the ground level hoisted by a large crane. That gave me the clue. If he could ride the steel, then the thief and the princess could ride the flying carpet.”

A carpet with a solid steel frame and cross-strapping was fabricated and connected to wires threaded through an overhead pulley and attached to a hand winch installed out of camera range. On cue, the carpet—on which Fairbanks and Julanne Johnston (the Princess) were seated—was levitated and then yanked toward an open window. “Once the suggestion of impending flight had been thus imparted, the rest was easy enough,” Walsh said.

Easy, perhaps, but dangerous as well. “Go to it, Irish,” Fairbanks told his director, “but if you drop us on a minaret, I’ll come back and haunt you.” Menzies devised much of the ensuing action:

We got a ninety-foot Llewellyn Crane and had the carpet suspended on six wires. There was Doug hanging on six wires he couldn’t see. They were each guaranteed to hold 400 pounds, but he said, “I would like something more than a guarantee in a place like this.” When the beam was started, the carpet would be left behind a little until the slack was taken up, and it gave us quite a thrill each time it was started. We also had to arrange for a traveling camera (which, by the way, is another thing the art director is involved in), and had a platform built for the cameraman which traveled with the crane. That was the first traveling shot.

When the magic carpet shots were made, Walsh established a local record by populating Menzies’ Great Square with 3,348 men, women, and children for a single day. The costumed extras started work on the first of eleven scenes featuring Fairbanks and Johnston at seven o’clock in the morning. Cigarettes and lunch were furnished by the studio, and six cameras covered the action, which continued until the light was lost at four in the afternoon.

Photography on The Thief of Bagdad wasn’t completed until January 1924, leaving scarcely two months to get the picture assembled, titled, tinted, and scored for its New York premiere. To underscore the magnitude of the event, Fairbanks worked a percentage deal with impresarios Morris Gest and F. Ray Comstock to present the picture at Broadway’s Liberty Theatre, where The Birth of a Nation had been housed for a historic forty-four-week run. Shown twice daily at a $2.20 top, Thief stood to generate an estimated $3,000 a week for Comstock & Gest, who filled the lobby with Hindoo singers and musicians, burned incense throughout the building, and adorned an adjacent billboard with an image of the Thief and his princess soaring high above Bagdad on their magic carpet. On the night of March 18, 1924, a flying wedge of the city’s finest cleared the way through a crush of fans for Fairbanks and his wife, and the ovation at the film’s conclusion—nearly 11:30—was thunderous. Fairbanks appeared onstage to take a bow, then brought Raoul Walsh up to join him. “Poetry in motion,” said Mary Pickford admiringly. “It cost a million, seven-hundred thousand.”

Fairbanks, Walsh, and cutter William Nolan had worked long hours to pare the film to fourteen reels for its first public showing. Although the notices were uniformly good—the Times called it “a feat of motion picture art which has never been equaled”—The Thief of Bagdad undeniably dragged in spots, and the men permitted themselves another four months of thoughtful tightening before the Los Angeles premiere on July 10. Word of the new miracle picture quickly reached the West Coast. The anticipation was palpable—Ernst Lubitsch made a point of seeing the sets before they were pulled down—but Fairbanks tinkered and fretted and refused to show it privately.

Menzies saw Fairbanks’ twelve-reel cut for the first time on the night of its Los Angeles opening. Hosting the premiere was Sid Grauman, Doug’s pal from San Francisco, whose new Hollywood Boulevard showplace, the Egyptian, would outdo the comparatively tame spectacle of the Liberty. Unlike any of the first-run New York houses, the Egyptian had the real estate to carry its architectural theme to the street with a forecourt promenade flanked by a bazaar of unusual shops. A carnival of street vendors and buskers drew attendees into the world of the Thief, while a Bedouin on the parapet performed the seemingly unnecessary task of calling out the film’s title.

Inside, the stage was a riot of hieroglyphics, terminating in a shimmering sunburst over the proscenium arch. Fleurs De Bagdad, a fragrance approximating the scent of a dry martini, perfumed the air as veiled usherettes led the guests to their seats. Members of the orchestra appeared in turbans and robes, and just after eight o’clock actor Milton Sills took the stage to convey the greetings of Douglas Fairbanks, who, he explained, was traveling in France. He went on to introduce the cast members, the key technical crew, and finally Menzies himself, who drew a warm and knowing round of applause from the crowd. Then the curtains parted to reveal a stage crowded with archways, minarets, and hanging rugs as the evening got under way with a lengthy prologue called “The City of Dreams.”

It was almost ten o’clock before the movie started, and Grauman had done such an elaborate job of packaging that most films would have seemed lacking by comparison. But Menzies’ opening tableau, posed in silhouette against a silvery moonlit desert, in which an old man imparts the story’s theme to the young boy at his feet, enveloped the crowd and in moments they were hooked. By the start of the second reel, the audience had assumed an almost childlike appreciation of the images, conquered, in the words of one spectator, “by the spell of some great undreamed of achievement by some marble-white East Indian temple and ivory palace in far Cathay.” At the end of the performance, well past midnight, the weary audience had witnessed an audacious injection of European spectacle into the most American form of commercial filmmaking and cheered accordingly.

The Thief of Bagdad played legitimate theaters for the rest of the year, a hard card for matinees because of its obvious appeal to children. (“I saw it when it first came out,” Orson Welles, who would have been nine years old, remembered. “I’ll never forget it.”) It was officially released by United Artists on January 1, 1925, and played widely in progressively shorter versions for the rest of the decade. And whatever else Bill Menzies did in his life, he would always be remembered, first and foremost, as the designer of The Thief of Bagdad.

* Buckland, by comparison, was fifty-seven at the time and Sven Gade forty-six.